Abstract

The study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial condition and mortality in Polish voivodeships. To achieve this objective, the relationship between the number of deaths before and during the pandemic and the financial condition of the provinces in Poland was studied. The study covered the years 2017–2020, for which a one-way ANOVA was used to verify whether there was a relationship between the level of a province’s financial condition and the number of deaths. The results of the study are surprising and show that before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a higher number of deaths in provinces that were better off financially, but the relationship was not statistically significant. In contrast, during the pandemic, a statistically significant strong negative correlation between these values was proven, which, in practice, shows that regions with better financial conditions had a higher number of deaths during COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The pandemic brought about by the SARS-CoV-2 virus changed the way the world functioned, the economy, and citizens’ lives. It also affected the condition of public finances, including self-government finances. The research completed by the key financial institutions has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on reducing the income of local administrative units—LAUs (municipalities, poviats, and voivodships), mainly as a result of decreasing the tax proceeds, and also on increasing the expenses, which finally resulted in decreased possibilities of contracting debt. Taking a look from a financial perspective makes it possible to comprehensively evaluate LAU functioning and its development capabilities [1]. Finance management in LAU should foster rational expenditure of public financial resources and make correct decisions regarding the management of monetary funds [2]. An important issue in LAU evaluation is its financial condition understood as the self-government’s ability to balance the recurring expenses with recurring sources of income while fulfilling the statutory tasks stipulated by the legal regulations. Other definitions of financial conditions take into account the possibility of financing the services on a continuous basis, the complexity of healthy finance, the ability to pay liabilities, and keeping the current level of services while maintaining the resistance to changes taking place over time [3]. The terms ‘financial condition’ and ‘financial situation’ are used interchangeably and defined in different ways [1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. In view of the research studies presented in this paper, it was decided that the most pertinent definition of financial condition will be the entity’s ability to timely meet its financial liabilities and the ability to sustain the services provided to the public [11].

Researchers all over the world have taken up numerous studies regarding the impact of COVID-19 on the activity of business entities. The research studies covered the influence of COVID-19 on the labor market and its inequalities [12], also taking into consideration people with disabilities [13], the school education process in Germany [14], and also on employment in LAUs in the USA, in particular, the situation of decreased income and increased expenses [15]. Other research studies also addressed the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and the mortality rate [16], the economic development rate [17], and the population size, which has an impact on burdening the healthcare system [18]. An analysis of the average life expectancy has shown an increased mortality risk during the pandemic, globally as well as in Poland [19], and more lost years of life expectancy than before the pandemic [20]. Additionally, the analysis covered the impact of COVID-19 nationally [21], in local sectors [22], and the federal budgets in the USA [23] on the subject of small and medium enterprises [24,25], their creditworthiness, and the system of guarantees and suretyships for SMEs [26]. Rama Iyer and Simkins [27] analyzed 81 articles regarding COVID-19 and the economy, according to citation counts in Google Scholar. They divided the selected articles into five thematic areas: investments and assets valuation, macroeconomics and banking, resources, business finance, and others. The studies regarded the capital market, labor market, education market, and condition of enterprises and economies on the macro scale.

Despite such extensive research available in the literature, the authors of this paper identified a shortage of studies regarding the financial condition of local administrative units (LAUs), such as cities and municipalities, second-tier administrative units (poviats), or self-governments of provinces (voivodeships). This is particularly important because, in a COVID-19 pandemic, regional economies were vulnerable to measures taken by central governments and instruments used in mitigating the pandemic’s effects. At the same time, measures taken on a national scale had an impact on regions and their economic situation, however, with diverse effects [28]. In this context, the financial situation of LAUs in that period should be considered in two aspects. On one side, from the point of view of the need to increase expenses to counteract the COVID-19 pandemic and to eliminate its effects, and parallel to that in terms of decreased current proceeds (i.a. from lease and rental fees, due to releasing entrepreneurs from the duty to pay such charges as a result of temporary suspension of their activity). The study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial condition and mortality in Polish regions. To achieve the goal, the relationship between the number of deaths and the financial condition of voivodeships in Poland in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the course of it.

This research study was based on the statistical and financial data found in budget implementation reports submitted by LAUs in Poland for the years 2017–2020 (latest available data). For each region, financial condition indicators (in relative terms) were computed, which made it possible to draw conclusions regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their financial standing, and its influence on the mortality rate.

The research scope covered 16 self-governing voivodeships in Poland [29,30]. Voivodeships in Poland are interchangeably referred to as regions (NUTS2), In the same breadth and they constitute one of the three levels of LAUs, along with municipalities and poviats.

The paper consists of several sections put in a logical sequence. Section one includes theoretical aspects connected with the discussed issues, prepared on the basis of the literature review. Additionally, it contains the analyses of the concept and factors of LAU’s financial condition as well as metrics of its evaluation. The next section discusses the scale and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on public finances and mortality rates in the regions. Section three presents the research study concept along with a description of the applied research methods. Section four shows the research results, and the last one contains conclusions.

2. The Concept of the Financial Condition of Regions

Each self-governing voivodeship functions and operates on the basis of the same regulatory framework. This includes not only the systemic and administrative norms but first and foremost the aspects of the functional affiliation, in accordance with which the relevant legal acts (Act on municipality self-government, poviat self-government, and voivodeship government) contain a catalog of statutory tasks, which imposes on each voivodeship the duty to carry out the same tasks (where one of the major tasks is fostering the development of a given voivodeship and creation of mechanisms and instruments to stimulate its development). In order that the enumerated tasks may be implemented, the legislator (i.a. in the Act on public finance or in the Constitution) indicated concrete sources of income, which are identical for every voivodeship. This means that in the legal and financial aspects the situation of all voivodeships at the starting point is the same.

Financial condition is in most cases treated as a synonym for the terms financial situation or financial standing. Dylewski et al. [7] pointed out that the concepts of financial condition and financial situation are almost identical and they added that the financial situation of a LAU is the state of finances that makes it possible to finance the implementation of statutory tasks, meeting the quantitative and qualitative requirements at a given time and in the future, which is specified by the time frame of the measurement, whereas, the financial condition is a result of decisions taken by local administrative units. Kopyściański and Rólczyński [6] supplemented this view saying that on the one hand the financial situation goal of an entity’s activity, and on the other hand an outcome of decisions taken earlier. Zawora [1], in turn, underlined that the financial condition is not only a derivative of implemented public tasks and projects, but it itself constitutes a source of pro-effective activities. According to Natrini and Ritonga [11], the financial condition describes a LAU’s ability to meet its financial liabilities, and based on the evaluation the self-government is able to specify how to meet the public needs, and how to make use of the resources in a more productive manner. A LAU in a good financial condition usually maintains an appropriate level of services despite a decrease in the fiscal income, it identifies long-term economic or demographic changes and adapts to them, and prepares resources to meet future needs. However, when under fiscal stress, a LAU usually faces problems with balancing the budget, experiences decreased levels of services, encounters difficulties with adapting to the socio-economic conditions, and has limited resources for financing future needs [31]. Proper assessment of a LAU’s financial condition is not an easy process due to the complexity of the phenomenon, and in order to make the assessment objective financial ratios are most often used in practice [10].

According to Ritonga et al. [5], only a few researchers attempted to explain the factors influencing the financial condition, quoting papers that enumerate the main determinants of the financial condition of LAUs in various countries. The most frequently indicated determinants include: population size/density, environmental conditions, the state of the local economic base, governmental policies and financial practices (tax levels) having an impact on local resources, labor costs, costs of capital and other production resources. It is possible to state that in general terms the factors that are the most frequently identified are broadly defined socio-economic ones. Due to the complexity of factors influencing the financial condition of self-government, there are not any easy or immediate ways to understand the diversification of the financial situations of self-government.

Taking into account the factors mentioned above, it is possible to distinguish six metrics that illustrate the financial condition of a LAU [4]:

- ability to meet short-term liabilities (short-term solvency);

- ability to meet operating liabilities (budget liquidity);

- ability to meet long-term liabilities (long-term solvency);

- ability to overcome unexpected events in the future (financial flexibility);

- ability to effectively execute property rights (financial independence);

- ability to provide services for the community (solvency in terms of services provision).

The issue of assessing a LAU’s financial condition is extremely important from the point of view of the informative value for decision-making and information purposes, as well as in view of the ability or inability to contract debt. Such an assessment provides information that facilitates decision-making with regard to implementing new tasks, and at the same time, it enables evaluation of the activities completed so far by the self-government within a specific scope [32]. The Polish literature on the subject presents the results of LAU’s financial condition evaluation obtained via various methods, including those based on empirical metrics or synthetic indicators. Researchers most often rely on, for example, the indicators proposed by the Ministry of Finance. In view of the differentiation between the concepts of financial condition and financial situation, they supplement the indicators proposed by the Ministry with additional metrics [3,10,33,34,35,36]. The most frequently applied indicators to assess LAU’s financial condition include the growth rate of income and expenses of LAUs in connection with the evaluation of the budget balances and with the operating result and the result of assets-related activities. The prevailing opinion is that any given unit’s condition is best reflected by the level of income and expenses per capita [33]. In self-governmental practice, indicators of this kind are applied in order to make comparisons in terms of time and space in relation to other LAUs (particularly the neighboring ones) which in some aspects may be competitors e.g., when potential investors choose a location for investment or when residents want to start their business activity. Among the concepts, the one that deserves attention is the approach taken by the Regional Accounting Chamber which in its analysis of threats to LAU’s financial management applies 9 criteria selected on the basis of indicators related to debt and financial results (total liabilities to income ratio, accumulated debt to income ratio, presence of payables due, individual debt repayment ratio, current expenses and debt to current income ratio, share of operating surplus/deficit in total income, lack of funds to cover an operating deficit, funds to be carried forward to next year’s budget based on LAU’s budget implementation balance sheet for the previous year, budget result to income ratio) [34]. Based on the outcome of LAU’s credibility evaluation carried out by means of discriminant analysis methods, Adamczyk & Dawidowicz [3] pointed out that indicators of the greatest importance are those which in their structure comprise categories such as total income value, level of own income, operating surplus value, debt level, and debt service cost. Additionally, their research has shown that more diverse sets of indicators should be applied when analyzing the financial condition of bigger LAUs, e.g., cities with poviat (second-tier of local government administration in Poland) rights: or voivodeships (regions).

3. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Economy

The first cases of infections with the SARC-CoV-2 virus were identified in the city of Wuhan (province of Hubei, China) in December 2019. In March 2020 the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced “a global pandemic” [37]. Initially, the virus spread in China and Europe, but in the second quarter of 2020, it was present all over the world [24,38]. The COVID-19 pandemic quickly sprawled out, resulting in human tragedies and economic losses, affecting both developed and developing countries. By the end of 2020, more than 79 million SARC-CoV-2 infections were detected, resulting in more than 1.7 million deaths all over the world [39]. In Poland, the first case of a SARC-CoV-2 infection was identified on 4 March 2020 in Lubuskie voivodeship [40]. From the beginning of the pandemic till the end of 2020, over 1.25 million SARC-CoV-2 infections were detected in Poland, and there were more than 27 thousand deaths caused by COVID-19 [39].

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic changed the way the world was functioning, affecting the economy and the citizens’ lives, it also left its mark on the condition of public finances [21]. No country escaped the negative consequences [41,42]. The financial outcomes of the pandemic include on the one hand decreased public revenues (mainly from taxes), which was caused i.a. by restricted business activity, lower income, and decreased activity of households [43,44]. On the other hand, there was a rise in COVID-related expenses to compensate for the losses experienced by enterprises [45]. Most surveyees (63%) of the OECD-European Committee of the Regions expected that the socio-economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic would have a significantly negative effect on local self-governments [46]. The findings of the initial studies and analyses were pessimistic with regard to the condition of local administrative units of each level [47,48]. In general, however, in many countries, the shock was partially cushioned by measures taken by central governments in the area of financial transfers [35]. In 2020 most countries introduced measures to support local and regional finances, to partially mitigate the effects of the economic shock. Cities and regions faced new challenges connected with the condition of local and regional economies, caused by the unpredictability of income levels and their reallocation in response to unpredicted events. Many self-governments had to cope with ‘the scissors effect’, i.e., increased levels of self-government expenses accompanied by decreased levels of income [46,49,50].

The research done by the World Bank has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a decrease in the income of local administrative units, mainly as a result of decreased proceeds from taxes, increased expenses caused by extraordinary items, decreased creditworthiness and reduced ability to contract debt [51,52]. The research on the impact of COVID-19 on regional finances in Europe, Asia, and Africa have shown an average decrease in income of 10% and an average increase in expenses of 5%. The main reason for that decrease was a reduction in proceeds from taxes and charges, lease or sale of assets, and smaller transfers from central governments. This entailed the need to borrow money in order to cope with crisis situations, and suspending or abandoning of key investments [49]. Authorities all over the world took steps to prevent the virus from spreading and to mitigate its effects, the result of which was a total or partial closure of the whole economy sectors [53], which in turn reduced the activity of business entities [43,44] triggering long-term effects [54], in particular for tourism and aviation industry [55]. They ranged widely from travel restrictions to national and regional lockdowns, keeping social distance, and other measures fostering the formation of unconventional geopolitical and socio-spatial movements [28]. In response to the virus propagation, authorities imposed restrictions on transport, economic and industrial activity in many countries.

The scope and scale of the COVID-19 impact were unprecedented and heterogeneous, with major implications for crisis management and political reactions [56], on the one hand being an object of scientific research, and on the other generating effects which will be experienced for many years. COVID-19 had an impact on everyday life, causing far-reaching consequences in the area of healthcare and economy, and also in the social dimension [57,58]. According to the analysts, the effects of those measures were dramatic, and business activity slumped on a global scale [38]. According to P. Brinca et al. [53], the pandemic was unique in terms of its nature and size, the uncertainty of its duration, and demand and supply shocks as well as various unforeseeable effects.

Economists compare the pandemic time with the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession of 2008. Even though the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic were different in terms of scope and time of impact [28], both of them influenced economies in many countries [59]. Still, according to economists, the COVID-19 pandemic has had the greatest impact on the economy since the Great Depression, at least in the short run. The preventive measures taken will influence the duration of the recession and the recovery time needed by the economy to return to the state from before the pandemic [23].

Nevertheless, the actual negative impact of COVID-19 turned out to be smaller than initially estimated. This was mainly due to the financial support received from the central government to strengthen the financial condition of local administrative units, maintaining fairly stable proceeds from taxes (mainly from the property tax) coming to the local budgets, and also savings in expenses, resulting from limiting or abandoning the local investments [50]. The financial situation of local administrative units in Poland was not found to be dramatically deteriorated, however, this may not justify the optimism of the central government in that regard [60]. Compared to central governments, self-governments have less effective instruments to respond to economic shocks, even though their proceeds are less sensitive to deterioration of the economic situation than those of central governments. The effectiveness of the tools being at the disposal of local or regional self-governments is smaller, the tools also have a moderate impact on the short-term situation of the budget and on the economic situation in the region [35,47]. The impact of COVID-19 on regional and local finances is not unambiguous due to the possibility of the continuation of the pandemic and its effects [61]. Undoubtedly, the negative impacts did not spread evenly. Due to the territorial aspect of the COVID-19 crisis [52], regions were not affected in the same way and its medium- and long-term effects are diverse [35,62]. The differentiating factors for this impact include e.g., the sensitivity of a region to the operation of global value chains [63], the share of vulnerable sectors (tourism, accommodation, catering) in the local economy [64], kinds of income and budget expenses in the particular types of LAUs. The development of the pandemic also affected the number of deaths and mortality rates, which reached levels not seen for a long time. This also drew the attention of scientists, who began to study the problem [58,65].

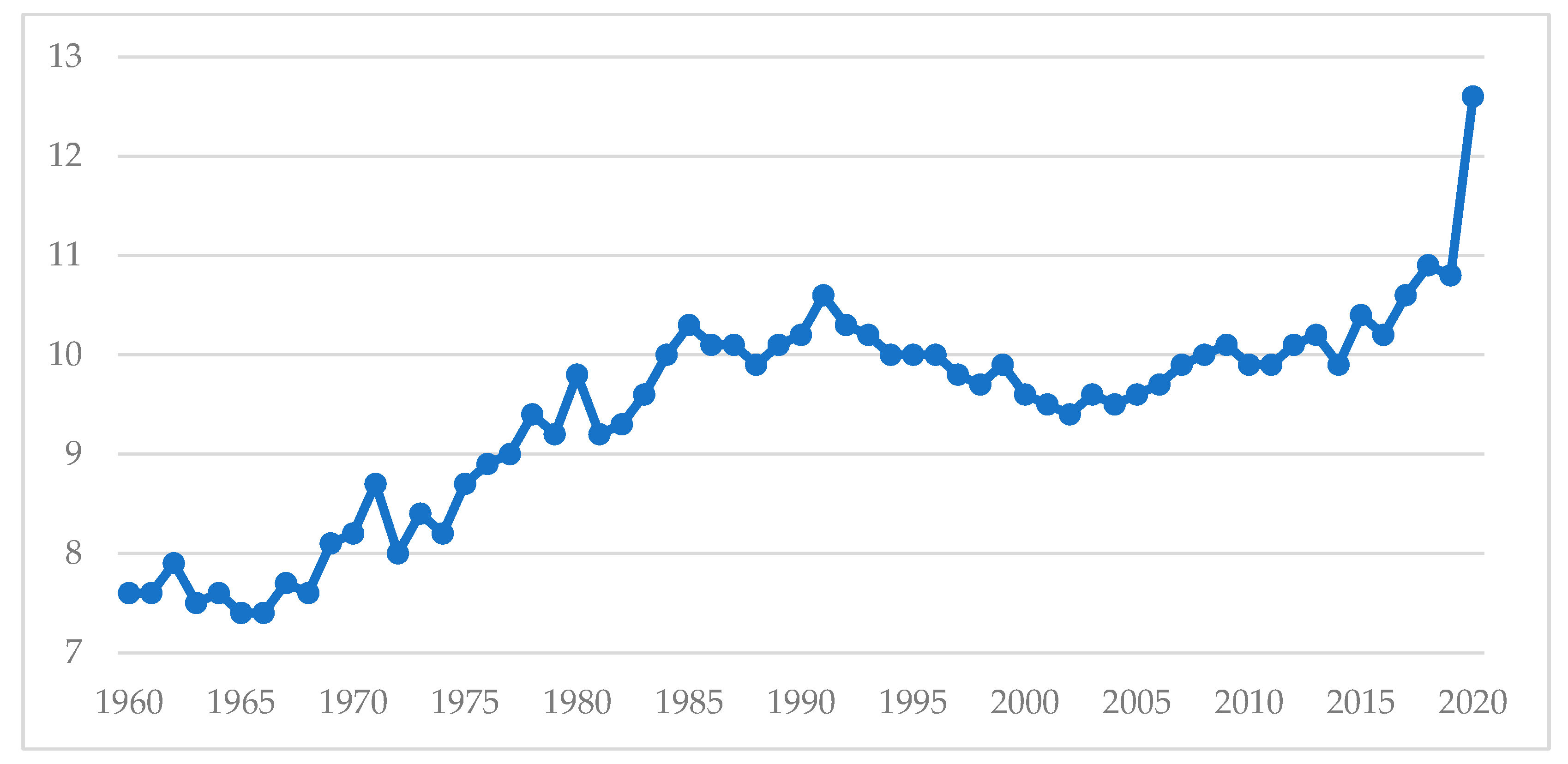

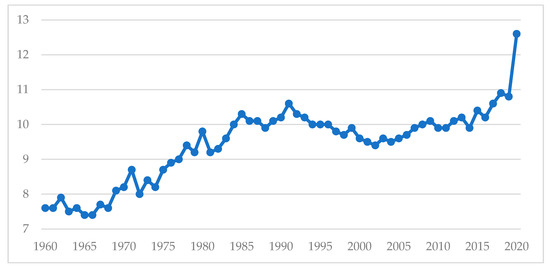

Even though over the last several decades the number of deaths all over the world decreased, the last years showed a slight rise in the number, and in 2020 the rise was considerable. Additionally in Poland, the year 2020 saw a significantly higher mortality rate compared to the previous years, which was directly and indirectly caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mortality rate per 1000 population in Poland over the years 1960–2020. Source: own study based on Data from World Bank [62].

4. Materials and Methods

The object of the research was local government units at the voivodeship level. In Poland are 16 LAUs, all of which were covered by the research (total sample). Based on the review of the literature regarding the financial condition of self-governments, legal regulations concerning their operation, and the range of suggested study indicators, and also based on the conclusions derived from the literature review and indicators used by the Central Statistical Office in Poland, a set of variables was selected to describe an LAU’s financial condition. To maintain the logic of the research process and the comparability of data, the input data used in the calculations come from the Local Data Bank of the Central Statistical Office, Regional Accounting Chambers, and from financial data derived from the budget reports of all the voivodeships for the years 2017–2020. The research period was divided into two parts, before and during the pandemic [66,67], enabling on the one side, to analyze of data from the years preceding the pandemic, which provides a baseline, and on the other side, the cyclical nature of the publication of data by the Polish Central Statistical Office (many months after the end of the year) makes 2020, the last complete data, covering the pandemic period. To ensure comparability of the analyzed data, they were expressed in relative terms (the source data which were expressed on the ‘per capita’ basis were left unchanged, whereas the remaining data were recalculated per 10,000 population, which was determined by the volume and clarity of received results). The study covered all the regional self-governments in Poland, i.e., 16 voivodeships (Table 1). Financial data of the analyzed LAUs used in the evaluation of the financial condition were presented in Appendix A (Table A1).

Table 1.

Features describing the financial situation of Polish regions.

Due to the short data presentation period connected with the COVID-19 pandemic by voivodeship (since 23 November 2020), the number of deaths in the particular voivodeships was assumed to specify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial condition of the regions in Poland. For that purpose, the mortality rate per 10,000 population was applied. A study of the relationship between mortality rates and socio-economic status was conducted by Aykaç and Etiler [65]. On the other hand, Yavuz and Etiler [58] looked for a relationship between urban health indicators and the third wave of COVID-19 on a regional basis. Their results indicate COVID-19 cases are higher in more developed cities with higher manufacturing sector activity.

The calculation of the financial condition was based on the financial data from all voivodeships and the synthetic indicator method which required standardization of the data. The study of the relationships required the previous specifications of the socioeconomic development level and the financial standing of the whole sample. The evaluation of the analyzed phenomenon applied the synthetic indicator method [68], the application of which involved several stages [69]. In the first stage, variables describing the phenomenon were selected [70,71,72] and used in constructing a matrix. The next stage consisted in converting the metrics in order to normalize them to basic features [73]. It was assumed that when a high value of the diagnostic variable for a given phenomenon is associated with beneficial growth, the feature is considered Larger-the-better (LTB), whereas, in a situation where a low value of the variable is beneficial for the phenomenon in question, it is deemed smaller-the-better (STB) [74,75]. The following formulas were applied in the calculations [69,71]:

where: Zij—diagnostic variable, falling within the range from 0 to 1;

xij —the feature value for a given region;

min xij—the lowest value of the feature among the examined regions;

max xij—the highest value of the feature among the examined regions.

Another step was the calculation of the synthetic indicator [71,76]:

where: qi—the calculated value of the synthetic indicator, zij—the standardized value of the j-th feature of the i-th unit, m—number of features included, αj—the weight of the j-th value variable.

The indicator values always fall within the (0, 1) range. When the indicator equals one, this means the maximum level of the analyzed phenomenon in relation to the other units in the sample. The last step in the analysis was to put in order the computed values of the synthetic indicator.

To estimate the financial situation of self-governing voivodeships, the analysis applied the following indicators meeting the factual and statistical criteria (i.e., it was assumed that the indicator differentiation level must exceed 10%) (Table 1).

Based on the obtained results, 3 classes of the financial situation of voivodeships were distinguished (good—I, average—II, weak—III), and the voivodeships were classified as per the following algorithm:

where: qi—the calculated value of the synthetic meter, —the mean value of the synthetic indicator, Sq—the standard deviation of the synthetic indicator.

The classification made it possible to obtain relatively equinumerous groups. In the pre-COVID-19 period, there were 4 voivodeships in Class I, 6 in Class II, and 6 in Class III. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 4 voivodeships in Class I, 7 in Class II, and 5 in Class III. Due to the specific nature of the data—the object of the study is the impact of the financial situation on the number of deaths, therefore, the dependent variable is a quantitative variable, whereas the independent variable is a factor variable (with 3 levels of variability), the voivodeships were studied in the 3 listed classes in terms of the numbers of deaths found there. The study applied the analysis of variance (i.e., comparison of intergroup variation with the intragroup variation) comparing the said groups in relation to the number of deaths in each voivodeship. For this purpose, a ‘one-way ANOVA’ was applied, which is a parametric test used to verify that there are statistically significant differences in the means between at least three groups. [77], which helped to obtain an answer to the question: was there a relationship between the financial situation of a given voivodeship and the number of deaths? The application of ANOVA made it possible to find an answer to the question of whether or not there was an actual difference between the classes, and if so, between which of them. In accordance with the ANOVA assumptions, its application is not possible for the whole population, but only for a sample. Therefore, it was decided to draw by lot 3 voivodeships from each class and include them in the analysis. Thus, a sample of 9 voivodeships was obtained for the pre-COVID-19 period (2017–2019) and a sample of 9 voivodeships for the COVID-19 period (2020). Thanks to that, the experimental form of the study was maintained. An important aspect in the context of the tools applied in the study was also the fact that it was carried out in equinumerous groups (3 voivodeships from each class).

5. Research Results

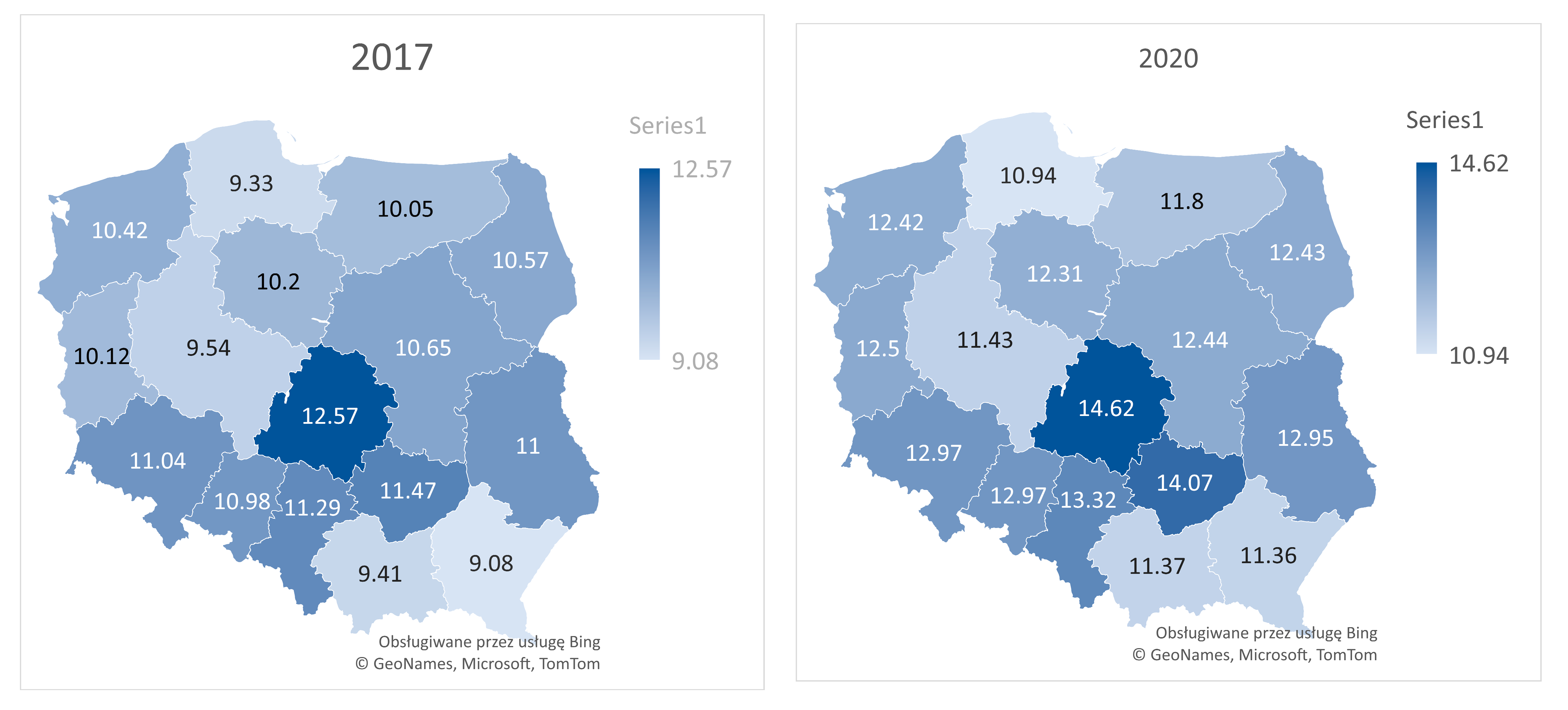

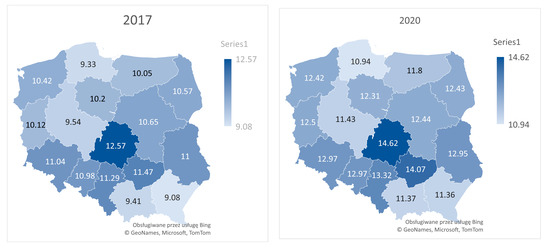

Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mortality rate in Poland ranged from 9.4 to 10.6 per 1000 population; the average rate in the last five years before the pandemic was 10.6, whereas in 2020 it reached the record level of 12.6, which means a double-digit rise of 16.7% compared to the previous year. Figure 2 presents the comparison of the number of deaths per 1000 population in the individual regions in 2017 (before the pandemic) and in 2020 (during the pandemic).

Figure 2.

Number of deaths per 1000 population in Poland. Source: own study based on Local Data Bank [58].

The Polish voivodeships where the number of deaths per 1000 population was the highest both in 2017 (12.57), and in 2020 were Łódzkie, Świętokrzyskie, Śląskie, Lubelskie, Dolnośląskie, and Opolskie. The death rate in those regions has for years been higher than in the other ones.

The lowest numbers of deaths in 2017 and in 2020 were seen in voivodeships: Pomorskie, Małopolskie, Podkarpackie, and Wielkopolskie. These regions have for years been characterized by a lower mortality rate than the national average. In the years analyzed, the number of deaths increased in each voivodship, with the highest number in the Podkarpackie (25.11%), Lubuskie (23.51%), and Świętokrzyskie (22.67%) voivodships.

In accordance with the previous assumptions and to ensure the logic of the research, the study period was divided into two stages, taking into account the two different situations, i.e., before and during the pandemic.

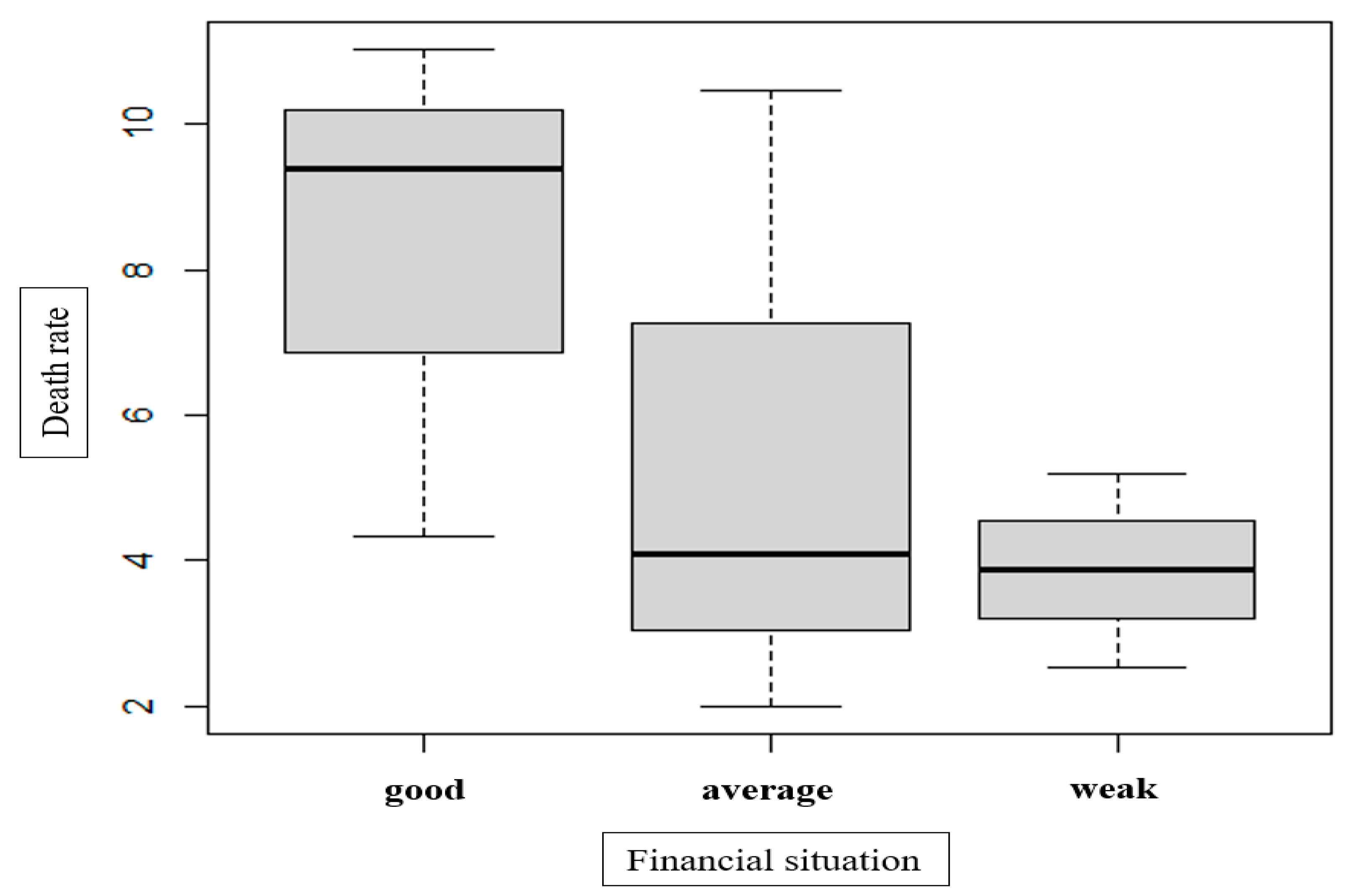

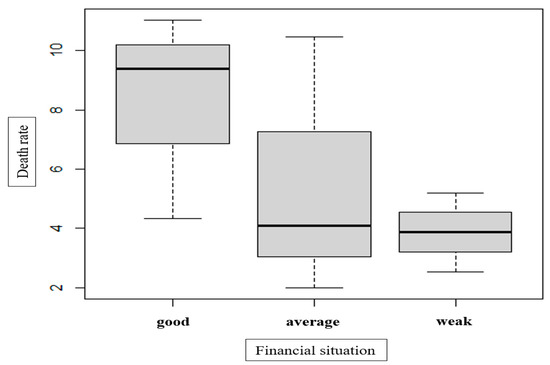

Stage 1—the pre-COVID-19 period.

In the first place, it was decided to optically verify the mortality rate depending on the financial situation of each of the analyzed classes. No outliers were found, and the differences between the groups seemed to be too small to enable drawing a conclusion on their significant differentiation. Additionally, it was not possible to conclude the impact of a voivodeship’s financial situation on the mortality rate within each of them (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dependency between the financial situation and the number of deaths in the individual analysed groups in the years 2017–2020 (before COVID-19). Source: own elaboration.

The subsequent step was the verification of the ANOVA assumptions about the parametric and homoscedasticity of the classes. To that end, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied, and its result showed there was no basis for stating a lack of normality in the groups. Bartlett’s test, in turn, showed there were no grounds to identify heterogeneity of variances (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of Shapiro–Wilk and Bartlett’s tests in the pre-COVID-19 period.

Meeting the ANOVA assumptions (quantitative variable measured on a quantitative scale, sample randomness, independence, normal distribution, no heteroscedasticity) made it possible to estimate the ONE-WAY ANOVA model (p = 0.335). The analysis has shown that in the pre-COVID-19 study period, there was no statistically significant correlation between the financial situation of a voivodeship and the mortality rate level.

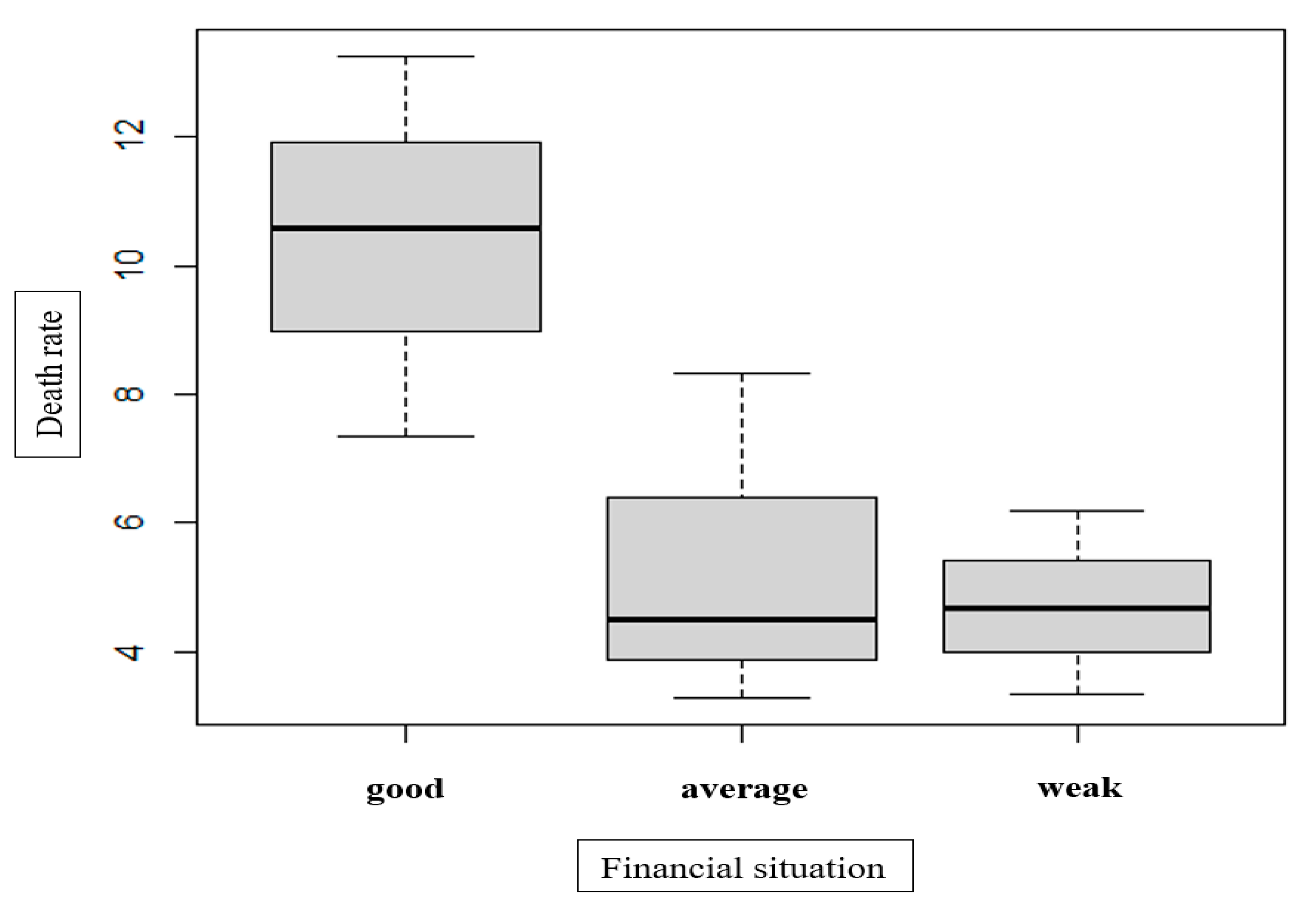

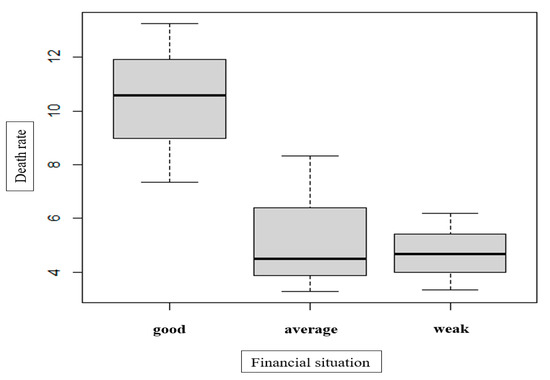

Stage 2—the COVID-19 period.

The study covering the COVID-19 period showed a bigger difference between the voivodeships with a good financial situation and particularly those with a weak one, in relation to the number of deaths. This difference is not visible between the other classes (Figure 4). However, without further analyses, it is not possible to state whether the difference was significant. Additionally, there were no outliers.

Figure 4.

Dependency between the financial situation and number of deaths in the individual analyzed groups in the COVID-19 period. Source: own elaboration.

The next step in the study was a verification of the ANOVA assumptions about the parametric and homoscedasticity of the groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to check the distribution, and its result showed there was no basis for stating a lack of normality in the groups. Bartlett’s test in turn showed there were no grounds to identify heterogeneity of variances (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett’s tests in the pre-COVID-19 period.

Additionally, in this case, all the ANOVA assumptions were met; therefore, the ONE-WAY ANOVA model was estimated (p = 0.0545). Due to the ANOVA assumption that a quantitative variable is measured on a quantitative scale, it was found that at the significance level of 10%, there was a statistically significant correlation between a voivodeship’s financial situation and the level of the mortality rate in the regions in the COVID-19 period. Therefore, it may be concluded that the level of the financial situation had a significant impact on the number of deaths. The data shown in the ONE-WAY ANOVA model made it possible to run subsequent studies in that respect. The next step was verifying the correlation strength by means of the experimental effect—the strength of the general effect, indicating the strength of the phenomenon, allowing the true significance of the outcome to be assessed, in this case (eta squared) indicating what proportion of the total variance in the dependent variable is explained by the effect. Based on the eta squared parameter (62%) it was found that the impact of the financial situation level on the number of deaths was strong (above 14%).

The last step was the post hoc analysis, making it possible to verify whether the voivodeships with various levels of financial situation significantly differed from each other in terms of the numbers of deaths. As a result of the analysis, a significant difference was found between voivodeships showing good and average financial situations (p = 0.044) as well as good and weak financial situations (p = 0.029). However, there was no relationship between voivodeships with average and weak financial situations (p = 0.760).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In the legal and financial aspect, the situation of all voivodeships at the starting point is the same. However, due to different kinds of budget proceeds (diverse income structures), the analysis of the financial condition of the individual LAUs can be interesting, especially during a crisis or pandemic. According to Auerbach et al. [23], the pandemic has had a very atypical impact on the state budget and local budget incomes. In Poland, the budgets of cities and municipalities rely on the personal income tax (PIT) and their own income, whereas budgets of voivodeship self-governments depend mainly on the corporate income tax (CIT). Amounts of the income proceeds may be different in times of crisis. Therefore, depending on the kind of local administrative unit and the budget proceeds structure, the impact of a crisis (including the one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic) may vary. Moreover, self-governments applied instruments to mitigate the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., exemption, tax relief, deferred payments) to different extents, depending on the availability of such measures and the administrative unit’s wealth; consequently, their impacts varied during the first wave of infections [78].

This study contributes to the growing field of research on the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on the sub-national level allows for territorial differences within a single country to be taken into account, while at the same time providing a seed and a kind of pilot for the next level of analysis, covering all EU regions.

Using a one-way ANOVA model, we provide evidence that despite the fact that before the pandemic (as of 2017) there was no statistically significant relationship, between the level of the financial health of a region and the level of mortality in its area, it is evident during the pandemic. Interestingly, the correlation between the financial situation and the number of deaths was negative. For the pre-COVID-19 period, the box plot (Figure 3) also shows that the financially better-off voivodeships featured higher numbers of deaths, however, the correlation was not statistically significant. This regularity was, however, found for the COVID-19 period (Figure 4). Hence, it is possible to state that administrative units with better finances experienced higher numbers of deaths in the COVID-19 period, and this phenomenon was not totally random, as the analysis of variance showed an impact of the financial situation on that phenomenon. Our findings are consistent with the results obtained by Aykac, Etiler [65] and Yavuz, Etiler [58].

Our study at this point has several limitations: the financial health of regions is influenced by their potential: the entrepreneurial resources of local and regional policymakers and subordinate officials, as well as the entrepreneurial forces and potential of local companies. These factors translate into the level of socio-economic development of the regions, which is to some extent conditioned by and at the same time determines the distribution of the population in a given area.

Due to the limitations of the study, the populations of individual voivodeships were not analyzed in terms of age structure, addictions, susceptibility to diseases, or population size, which has an influence on burdening the healthcare service and lower effectiveness of treatment in countries/regions characterized by large populations [17,18]. Voivodeships in a better financial condition (Class I) showed higher mortality rates than those with a worse financial standing (Class II and III). Theoretically, the richer regions should spend more on healthcare, which in turn should translate into lower mortality. The results show the need for appropriate management of health care and accessibility to medical services. The better financial health of the voivodeship does not guarantee better access to medical services, including specialized ones. However, this requires further research, including into the efficiency of healthcare financing and medical services in the regions not only during the crisis [79]. However, without a more in-depth analysis of the social structure in each of the voivodeships and an analysis of the expense structure (including the amounts of spending on healthcare in the individual regions), it is not possible to know the reason why this correlation occurred.

In this context, it makes sense to continue the research, expanding it to include aspects related to demographic factors and other determinants of socioeconomic development. Policymakers from regions with higher mortality rates and/or lower levels of financial health should analyze initiatives and implement solutions in other regions where this works better (taking into account the potential differentiating characteristics of these regions). It also seems to be an interesting step to analyze the data with a distinction of metropolitan areas—analyses of regions where metropolises operate can lead to a situation where the financial aspects of the operation and level of development of the metropolis raise the indicators of the financial health of the region, while at the same time municipalities outside the range of strong influence of the metropolis can be low developed but functioning within some correct framework. Extraordinary situations, such as a crisis caused by a pandemic, are a verifier of the effectiveness and efficiency of such entities. At the same time, more difficult-to-measure sociological aspects remain important, such as beliefs about the meaning of medical treatment, vaccination uptake, etc. These considerations show the vast possibilities for further analysis of this phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; methodology, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; validation, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; formal analysis, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; investigation, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; resources, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; data curation, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; writing—review and editing, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; visualization, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P.; supervision, K.B., M.G.-K., E.O.-K. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education under the name “Regional Excellence Initiative” in the years 2019–2022; project number 001/RID/2018/19; the amount of financing: PLN 10,684,000.00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We used statistics available in international and national databases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Financial data of the analyzed LAUs used in evaluation of the financial condition.

Table A1.

Financial data of the analyzed LAUs used in evaluation of the financial condition.

| Voivodeship | Year | Property Income Per Capita (PLN) | Total Expenses Per Capita (PLN) | Operating Surplus as % of Total Income Per 10,000 Population (%) | Ratio of Financing Capital Expenditure with Operating Surplus (%) | Planned Amount of Debt Per Capita (for a Given Year) (%) | Investment Volume Indicator Per 10,000 Population (PLN) | Ratio of Annual Debt to Total Income (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2017 | 73.75 | 385.95 | 0.0474 | 0.4716 | 237.76 | 1,162,886 | 59.70 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 23.84 | 330.65 | 0.0685 | 0.6727 | 130.82 | 703,457 | 39.47 | |

| Lubelskie | 100.29 | 401.41 | 0.0601 | 0.3536 | 305.89 | 1,476,307 | 75.29 | |

| Lubuskie | 78.44 | 471.64 | 0.0986 | 0.2752 | 169.90 | 1,579,370 | 39.00 | |

| Łódzkie | 32.02 | 259.96 | 0.0582 | 0.8073 | 110.77 | 506,010 | 39.25 | |

| Małopolskie | 117.79 | 381.79 | 0.0411 | 0.3436 | 128.38 | 1,601,728 | 32.55 | |

| Mazowieckie | 13.65 | 426.96 | 0.0498 | 1.3508 | 221.87 | 940,106 | 46.85 | |

| Opolskie | 145.16 | 451.79 | 0.1284 | 0.3540 | 137.67 | 1,739,733 | 28.41 | |

| Podkarpackie | 111.75 | 430.80 | 0.0608 | 0.3656 | 107.86 | 1,568,676 | 24.34 | |

| Podlaskie | 158.00 | 439.93 | 0.1101 | 0.3448 | 34.13 | 1,813,484 | 7.12 | |

| Pomorskie | 46.62 | 359.26 | 0.0607 | 0.4794 | 114.02 | 1,036,237 | 32.40 | |

| Śląskie | 22.15 | 268.47 | 0.0353 | 0.7206 | 150.59 | 612,495 | 55.06 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 113.11 | 386.00 | 0.1043 | 0.3745 | 132.64 | 1,430,997 | 32.38 | |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 44.93 | 363.88 | 0.0500 | 0.3279 | 209.80 | 779,372 | 58.86 | |

| Wielkopolskie | 28.21 | 336.23 | 0.0531 | 0.6101 | 95.58 | 989,017 | 29.33 | |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 131.81 | 472.55 | 0.0646 | 0.2828 | 138.55 | 1,841,225 | 29.33 | |

| Dolnośląskie | 2018 | 80.92 | 396.63 | 0.0545 | 0.6025 | 210.21 | 1,134,539 | 48.61 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 50.38 | 392.36 | 0.0681 | 0.4679 | 131.44 | 1,154,862 | 34.47 | |

| Lubelskie | 77.51 | 437.30 | 0.0621 | 0.3284 | 335.83 | 1,638,904 | 82.97 | |

| Lubuskie | 73.22 | 445.81 | 0.1100 | 0.3260 | 173.63 | 1,445,360 | 41.18 | |

| Łódzkie | 43.86 | 324.46 | 0.0743 | 0.6496 | 125.31 | 948,820 | 37.40 | |

| Małopolskie | 87.81 | 386.66 | 0.0469 | 0.4711 | 122.21 | 1,361,976 | 30.37 | |

| Mazowieckie | 26.12 | 489.37 | 0.0568 | 1.2562 | 185.81 | 1,340,993 | 33.79 | |

| Opolskie | 174.74 | 504.68 | 0.1160 | 0.2828 | 119.31 | 2,130,931 | 22.66 | |

| Podkarpackie | 176.97 | 537.23 | 0.0917 | 0.4202 | 92.08 | 2,612,734 | 16.36 | |

| Podlaskie | 249.23 | 671.03 | 0.0885 | 0.1622 | 107.43 | 3,858,776 | 18.00 | |

| Pomorskie | 113.08 | 449.74 | 0.0632 | 0.3640 | 93.97 | 1,808,170 | 20.98 | |

| Śląskie | 50.18 | 318.73 | 0.0474 | 0.7743 | 132.94 | 967,667 | 38.30 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 195.50 | 564.67 | 0.1181 | 0.2499 | 121.01 | 3,102,732 | 22.94 | |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 64.50 | 428.76 | 0.0900 | 0.3529 | 254.22 | 1,455,065 | 63.70 | |

| Wielkopolskie | 27.93 | 363.97 | 0.0506 | 0.6231 | 115.79 | 1,003,941 | 32.70 | |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 198.39 | 559.71 | 0.0531 | 0.1962 | 172.37 | 2,547,042 | 31.15 | |

| Dolnośląskie | 2019 | 58.71 | 384.33 | 0.0614 | 0.6678 | 182.80 | 1,085,665 | 44.92 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 45.81 | 431.88 | 0.1112 | 0.6907 | 130.31 | 1,444,978 | 30.09 | |

| Lubelskie | 190.03 | 576.78 | 0.0707 | 0.2977 | 329.60 | 2,872,741 | 58.33 | |

| Lubuskie | 108.97 | 517.12 | 0.1071 | 0.2662 | 210.40 | 1,967,707 | 43.68 | |

| Łódzkie | 72.16 | 387.98 | 0.0641 | 0.4970 | 251.78 | 1,261,237 | 63.47 | |

| Małopolskie | 63.02 | 390.55 | 0.0565 | 0.6752 | 108.99 | 1,184,400 | 26.26 | |

| Mazowieckie | 40.87 | 597.31 | 0.0504 | 0.8752 | 148.38 | 1,912,433 | 24.15 | |

| Opolskie | 165.29 | 519.24 | 0.1483 | 0.3971 | 100.60 | 2,056,248 | 17.95 | |

| Podkarpackie | 151.17 | 496.82 | 0.0959 | 0.5179 | 99.83 | 2,146,005 | 18.33 | |

| Podlaskie | 368.60 | 835.10 | 0.0869 | 0.1444 | 183.75 | 5,321,012 | 24.55 | |

| Pomorskie | 155.75 | 563.64 | 0.0773 | 0.3706 | 114.64 | 2,683,275 | 20.82 | |

| Śląskie | 38.76 | 328.39 | 0.0522 | 0.9840 | 107.31 | 881,677 | 29.34 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 179.66 | 551.18 | 0.1579 | 0.3966 | 108.20 | 2,787,006 | 19.23 | |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 91.90 | 473.45 | 0.0878 | 0.3930 | 254.60 | 1,506,189 | 53.72 | |

| Wielkopolskie | 91.59 | 450.83 | 0.0548 | 0.4598 | 126.19 | 1,846,122 | 28.50 | |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 83.45 | 463.86 | 0.0998 | 0.5052 | 146.67 | 1,574,015 | 31.24 | |

| Dolnośląskie | 2020 | 69.65 | 381.86 | 0.0930 | 1.2270 | 141.81 | 1,044,769 | 29.84 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 67.38 | 510.33 | 0.1223 | 0.7856 | 129.51 | 1,747,413 | 23.97 | |

| Lubelskie | 95.78 | 474.97 | 0.0461 | 0.3877 | 326.64 | 1,244,255 | 66.04 | |

| Lubuskie | 150.71 | 613.78 | 0.1585 | 0.3832 | 227.17 | 2,548,829 | 37.41 | |

| Łódzkie | 84.01 | 419.42 | 0.0851 | 0.6019 | 230.67 | 1,541,501 | 52.18 | |

| Małopolskie | 151.79 | 591.41 | 0.0360 | 0.3422 | 142.89 | 2,150,655 | 23.75 | |

| Mazowieckie | 29.37 | 614.11 | 0.0422 | 1.0638 | 174.94 | 1,398,053 | 26.82 | |

| Opolskie | 125.31 | 554.43 | 0.1959 | 0.7580 | 81.09 | 1,632,610 | 12.67 | |

| Podkarpackie | 173.44 | 565.19 | 0.0884 | 0.4552 | 127.19 | 2,492,443 | 21.10 | |

| Podlaskie | 269.82 | 728.75 | 0.0961 | 0.2196 | 244.34 | 3,679,158 | 34.34 | |

| Pomorskie | 72.66 | 455.41 | 0.0790 | 0.6100 | 104.53 | 1,428,247 | 22.13 | |

| Śląskie | 93.96 | 426.40 | 0.0347 | 0.3696 | 101.16 | 1,745,141 | 24.65 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 110.18 | 478.39 | 0.2279 | 0.8256 | 95.66 | 1,903,624 | 17.22 | |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 198.59 | 588.08 | 0.1168 | 0.3681 | 242.27 | 2,773,166 | 39.62 | |

| Wielkopolskie | 108.33 | 469.58 | 0.0739 | 0.6963 | 116.78 | 1,926,712 | 22.48 | |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 140.38 | 566.76 | 0.1179 | 0.5512 | 173.38 | 2,212,195 | 28.52 |

Source: own study based on resolutions on adopting budgets and long-term financial forecasts for voivodeships, resolutions on amending budgets and long-term financial forecasts for voivodeships for the years 2017–2020, and budget implementation reports.

References

- Zawora, J. Analiza wskaźnikowa w procesie zarządzania finansami samorządowymi. Zarządzanie Finansami i Rachunkowość 2015, 3, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mrówczyńska-Kamińska, A.; Kucharczyk, A.; Średzińska, J.; Analiza finansowa w jednostkach samorządu terytorialnego na przykładzie Miasta i Gminy Środa Wlkp. In Zeszyty Naukowe Szkoły Głównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego. In Ekonomika i Organizacja Gospodarki Żywnościowej; 2011; p. 89. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-b7ee59fd-e724-4c90-be30-d5983b8215b3 (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Adamczyk, A.; Dawidowicz, D. Wartość informacyjna wskaźników oceny kondycji finansowej jednostek samorządu terytorialnego. Ekon. Probl. Usług 2016, 125, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, I.T.; Clark, C.; Wickremasinghe, G. Assessing financial condition of local government in Indonesia: An exploration. Public Munic. Financ. 2012, 1, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Ritonga, I.; Clark, C.; Wickremasinghe, G. Factors Affecting Financial Condition of Local Government in Indonesia. J. Account. Investig. 2019, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopyściański, T.; Rólczyński, T. Analiza wskaźników opisujących sytuację finansową powiatów w województwie dolnośląskim w latach 2006–2012. Stud. Ekon. 2014, 206, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dylewski, M.; Filipiak, B.; Gorzałczyńska-Koczkodaj, M. Analiza Finansowa Budżetów Jednostek Samorządu Terytorialnego; Municipium: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Filipiak, B. (Ed.) Metodyka Kompleksowej Oceny Gospodarki Finansowej Jednostki Samorządu Terytorialnego; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowska, E. Przesłanki racjonalnej polityki budżetowej w jednostkach samorządu terytorialnego. In Funkcjonowanie Samorządu Terytorialnego—Uwarunkowania Prawne i Społeczne; Gołębiowska, W.A., Zientarski, P.B., Eds.; Kancelaria Senatu RP: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, M. Wyznaczniki sytuacji finansowej gminy—Ocena istotności za pomocą analizy skupień. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu. Nauki o Finansach 2011, 9, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Natrini, N.D.; Taufiq Ritonga, I. Design and Analysis of Financial Condition Local Government Java and Bali (2013–2014). SHS Web Conf. 2017, 34, 03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieli, A.; Olmstead-Rumsey, J. Sector-Specific Shocks and the Expenditure Elasticity Channel During the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3593514 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Jones, M. COVID-19 and the labour market outcomes of disabled people in the UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewenig, E.; Lergetporer, P.; Werner, K.; Woessmann, L.; Zierow, L. COVID-19 and educational inequality: How school closures affect low- and high-achieving students. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 140, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Loualiche, E. State and local government employment in the COVID-19 crisis. J. Public Econ. 2020, 193, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mouhayyar, C.; Jaber, L.T.; Bergmann, M.; Tighiouart, H.; Jaber, B.L. Country-level determinants of COVID-19 case rates and death rates: An ecological study. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 69, 14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hiyoshi, A.; Montgomery, S. COVID-19 case-fatality rate and demographic and socioeconomic influencers: Worldwide spatial regression analysis based on country-level data. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöley, J.; Aburto, J.M.; Kashnitsky, I.; Kniffka, M.S.; Zhang, L.; Jaadla, H.; Dowd, J.B.; Kashyap, R. Life expectancy changes since COVID-19. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arolas, H.P.; Acosta, E.; López-Casasnovas, G.; Lo, A.; Nicodemo, C.; Riffe, T.; Myrskylä, M. Years of life lost to COVID-19 in 81 countries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grittayaphong, P.; Restrepo-Echavarria, P. COVID-19: Fiscal Implications and Financial Stability in Developing Countries; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Padovani, E.; Iacuzzi, S.; Jorge, S.; Pimentel, L. Municipal financial vulnerability in pandemic crises: A framework for analysis. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2021, 33, 87–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, A.; Gale, B.; Lutz, B.; Sheiner, L. Fiscal Effects of COVID-19; For Presentation at Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/fiscal-effects-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Hossain, M.R.; Akhter, F.; Sultana, M.M. SMEs in COVID-19 Crisis and Combating Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and A Case from Emerging Economy. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2022, 9, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuta-Tokarska, B. SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. The Sources of Problems, the Effects of Changes, Applied Tools and Management Strategies—The Example of Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Phoumin, H.; Rasoulinezhad, E. COVID-19 and regional solutions for mitigating the risk of SME finance in selected ASEAN member states. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.R.; Simkins, B.J. COVID-19 and the Economy: Summary of research and future directions. Finance Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, L.; Dong, K. What matters for regional economic resilience amid COVID-19? Evidence from cities in Northeast China. Cities 2021, 120, 103440. [Google Scholar]

- Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z Dnia 2 Kwietnia 1997 r.; Dz. U. 1997, nr 78, poz. 483; 1997. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19970780483 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Ustawa z Dnia 24 Lipca 1998 r. o Wprowadzeniu Zasadniczego Trójstopniowego Podziału Terytorialnego Państwa; Dz.U. 1998 nr 96 poz. 603. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19980960603 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Di Napoli, T.P. Local Government Management Guide—Financial Condition Analysis. Division of Local Government and School Accountability. 2019, p. 2. Available online: https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/local-government/publications/pdf/financialconditionanalysis.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Osiński, J.; Zawiślińska, I. Financial Condition of Local Government in Poland vs StructuralReforms of Municipal Government in Scandinavian States. Przegląd Politol. 2020, 4, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśny, J. Kondycja finansowa wybranych jednostek samorządu terytorialnego województwa małopolskiego w nowej perspektywie finansowej Unii Europejskiej. Nierówności Społeczne A Wzrost Gospod. 2017, 49, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regionalna Izba Obrachunkowa. Analiza Ryzyka Wystąpienia Zagrożeń w Gospodarce Finansowej Jednostek Samorządu Terytorialnego Województwa Opolskiego za 2019 r. Z Uwzględnieniem Art. 243 Ustawy O Finansach Publicznych; RIO Opole: Opole, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swianiewicz, P.; Łukomska, J. Ewolucja sytuacji finansowej samorządów terytorialnych w Polsce po 2014 roku; Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ślebocka, M. Wykorzystanie Analizy Finansowej w Jednostkach Samorządu Terytorialnego Dla Potrzeb Przedsięwzięć Rewitalizacyjnych na Przykładzie Miasta Łodzi. Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług 2018, 129, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Situation Report-67; World Health Organ: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situationreports (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Brodeur, A.; Gray, D.; Islam, A.; Bhuiyan, S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1007–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/pierwszy-przypadek-koronawirusa-w-polsce (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Chudik, A.; Mohaddes, K.; Pesaran, H.; Raissi, M.; Rebucci, A. Economic Consequences of COVID-19: A Counterfactual Multi-Country Analysis, 19 October 2020. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/economic-consequences-covid-19-multi-country-analysis (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Goldbach, S.; Nitsch, V. COVID-19 and Capital Flows: The Responses of Investors to the Responses of Governments. Open Econ. Rev. 2022, 33, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio-Chanona, R.M.; Mealy, P.; Pichler, A.; Lafond, F.; Farmer, J.D. Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: An industry and occupation perspective. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Air Quality—A Global Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiąg, W. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na polskie finanse publiczne—Źródła finansowania, wydatki, procedury. Kwart. Prawno-Finans. 2020, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Regional and Local Governments: Main Findings from the Joint CoR-OECD Survey; OECD Regional Development Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; p. 9.

- Raport Samorząd: Pomiędzy Nadzwyczajnymi Zadaniami a Ograniczonymi Możliwościami—Samorząd Terytorialny w Czasie Pandemii; Fundacja GAP, Open Eyes Economy: Kraków, Poland, 2020.

- Gołaszewski, M. Samorządy z Nadwyżką Czy Ukrytym Deficytem. 2021. Available online: https://www.miasta.pl/aktualnosci/samorzady-z-nadwyzka-czy-ukrytym-deficytem (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Legrand, J.-B. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Subnational Finances, Emergency Governance for Cities and Regions, Analitysc Note #03; 2021. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/Cities/publications/Policy-Briefs-and-Analytics-Notes/Analytics-Note-03-The-Impact-of-the-Covid-19-pandemic-on-Subnational-Finances (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Dougherty, S.; de Biase, P. State and Local Government Finances in the Time of COVID-19, Research-Based Policy Analysis and Commentary from Leading Economists. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/state-and-local-government-finances-time-covid-19 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Kochanov, P.; Hong, Y.; Mutambatsere, E. COVID-19’s Impact on Sub-National Governments; International Finance Corporation World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ARAL, N.; Bakir, H. Spatiotemporal Analysis of COVID-19 in Turkey. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 76, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinca, P.; Duarte, J.B.; Faria-E-Castro, M. Measuring labor supply and demand shocks during COVID-19. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 139, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Pedraza, A.; Ruiz-Ortega, C. Banking sector performance during the COVID-19 crisis. J. Bank. Finance 2021, 133, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanga, D.; Hua, M.; Ji, Q. Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 36, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis and recovery across levels of government. In Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19): Contributong to a Global Effort; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr. Med. Res. Pract 2020, 10, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, M.; Etiler, N. The correlation between attack rates and urban health indicators during the third wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Turkey. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 986273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Igan, D.; Martinez Peria, M.S.; Pierri, N.; Presbitero, A.F. Government intervention and bank markups: Lessons from the global financial crisis for the COVID-19 crisis. J. Bank. Financ. 2021, 133, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyk-Siekierska, K. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na sytuację finansową i funkcjonowanie jednostek samorządu terytorialnego. Zesz. Nauk. Małopolskiej Wyższej Szkoły Ekon. W Tarn. 2021, 51, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska-Misiąg, E. Finanse jednostek samorządu terytorialnego w Polsce w pierwszym roku pandemii, Finanse jednostek samorządu terytorialnego w Polsce w pierwszym roku pandemii. Optimum. Econ. Stud. 2022, 107, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Municipal Finance©; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37205 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Delardas, O.; Kechagias, K.S.; Pontikos, P.N.; Giannos, P. Socio-Economic Impacts and Challenges of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): An Updated Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Yueb, X.-G. Multidimensional effect of COVID-19 on the economy: Evidence from survey data. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykaç, N.; Etiler, N. COVID-19 mortality in Istanbul in association with air pollution and socioeconomic status: An ecological study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 13700–13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestdagh, B.; Sempiga, O.; Van Liedekerke, L. The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K. Assessment of the Similarity of the Situation in the EU Labour Markets and Their Changes in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, M.; Strzelczyk, W. Pomiar kondycji finansowej jednostek samorządu lokalnego—Kwerenda międzynarodowa. Nierówności Społeczne A Wzrost Gospod. 2017, 49, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, A.; Janulewicz, P. Klasyfikacja gmin wiejskich województwa lubelskiego na podstawie rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego. Folia Pomeranae Univ. Technol. Stetin. Folia Pomer. Univ. Technol. Stetin. 2009, 275, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki, B.; Lewandowska-Gwarda, K. Klasyfikacja, wizualizacja i grupowanie danych przestrzennych, w: Ekonometria przestrzenna. In Metody i Modele Analizy Danych Przestrzennych; Wydawnictwo CH Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, F.; Lira, J. Statystyka Opisowa; Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej: Poznań, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parysek, J.J.; Wojtasiewicz, L. Metody Analizy Regionalnej i Metody Planowania Regionalnego; Studia PWN, LXIX: Warszawa, Poland, 1978; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Feltynowski, M. Planowanie przestrzenne a rozwój społeczno-gospodarczy w gminach wiejskich województwa łódzkiego; Foila Pomeranae Universitatis Technologiae Stetinensis, Oeconomica: Szczecin, Poland, 2009; Volume 268, pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut-Jaworska, M.; Ociepa-Kicińska, E. Smart Specialisation as a Strategy for Implementing the Regional Innovation Development Policy—Poland Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobko, R.; Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L.; Oklevik, O. The Role of the Financial Condition in the Development of Coastal Municipalities in Poland. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klóska, R. Statystyczna Analiza Poziomu Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego w Polsce—W Ujęciu Regionalnym, Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Bankowej w Poznaniu 2012, nr 42, Przestrzeń w Nowych Realiach Gospodarczych; Space in New Economic Reality; Wyższa Szkoła Bankowa: Poznań, Poland, 2012; pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Moder, K. Alternatives to F-Test in One Way ANOVA in case of heterogeneity of variances (a simulation study). Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2010, 52, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kańduła, S.; Przybylska, S. Financial instruments used by Polish municipalities in response to the first wave of COVID-19. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowicz, I.; Rudawska, I. Struggling with COVID-19—A Framework for Assessing Health System Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).