Research on the Experience of Influencing Elements and the Strategy Model of Children’s Outpatient Medical Services under the Guidance of Design Thinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Current Situation of Pediatric Outpatient Clinics in Shanghai Urban Hospitals

2.2. Current Situation of Pediatric Outpatient Clinic in Shanghafi Xinhua Hospital

3. Methods

3.1. Guiding Concept: Design Thinking Models

- Discover stage: explore, gain insights, and gather user needs.

- Define stage: problem definition and refinement, providing a framework.

- Develop stage: solution creation and exploration.

- Deliver stage: service testing and evaluation.

3.2. Research Framework

- The first stage: The preliminary investigation of the pediatric outpatient clinic in the hospital. This stage includes preliminary field research and interviews and the preliminary construction of questionnaires. Specifically, at the beginning of the first phase (empathy), the authors conducted preliminary interviews with pediatric patients and their parents in the outpatient clinic of Shanghai Xinhua Hospital, on-site, by telephone, or on WeChat (social media software). The role of this stage is to obtain a preliminary understanding of the medical environment, medical process, stakeholders, and research contact points of the pediatric outpatient department of the hospital, which can pave the way for subsequent element analysis based on questionnaire surveys.

- The second stage: The collection of elements that affect child outpatients’ medical service experiences. This stage includes drawing up questionnaires, implementing questionnaire surveys, analyzing questionnaire data, and extracting main elements. Specifically, first, the content of the questionnaire was designed according to the results of field research. Second, implement questionnaire survey. Third, SPSS software (Mac 22.0) was used to conduct the descriptive analysis, satisfaction analysis, and principal component analysis of the questionnaire data. The purpose of the descriptive analysis is to identify the main dimensions that affect child outpatients’ medical service experiences, and to provide a preliminary scope for subsequent in-depth analysis. The purpose of the satisfaction analysis was to determine whether current child outpatients and their parents were satisfied with the outpatient medical service experience based on the main dimensions. The purpose of principal component analysis is to perform dimensionality reduction analysis on the main dimensions in order to further determine the specific influencing elements. Fourth, further supplementary analysis were conducted through structured interviews to supplement the influencing elements. Fifth, through the analysis of the results, the influencing elements of child outpatients’ medical service experiences and the improvement of the strategy of children’s outpatient medical services were summarized in order to ensure an accurate and complete understanding of the needs of child patients. It should be noted that a single questionnaire analysis or questionnaire survey method cannot guarantee an accurate and comprehensive summary of elements affecting child outpatients’ medical service experiences. Therefore, this study conducted a comprehensive analysis of the questionnaire from multiple perspectives. At the same time, structured interviews are used to supplement the analysis results of the questionnaire survey and strive to achieve a comprehensive summary and analysis of influencing elements.

- The third stage: Conceptual solution development. After completing the first and second phases (definition), a strategy model for improving the outpatient medical service experience for children needed to be generated based on the influencing elements. This stage was mainly performed using the brainstorming method. Brainstorming methods include brainwriting, storyboards, and mind maps. At this stage, the evaluation of ideas is discouraged and no constraints are imposed, which can lead to increased inspiration and creativity.

- The fourth stage: Solution feedback and evaluation. The strategy model was evaluated and the effectiveness of the strategy model was tested through questionnaire satisfaction survey analyses and simulated scenarios.

3.3. Nodal Method: Initial Field Research

3.4. Node Method: Questionnaire Survey and Analysis

3.5. Node Method: Structured Interviews

3.6. Node Methods: Strategy Model Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Field Research and Analysis

4.1.1. Preliminary Investigation and Analysis of the Pediatric Outpatient Clinic

4.1.2. Analysis of Medical Treatment Process for Child Patients

4.1.3. Stakeholder Analysis

4.1.4. Service Touchpoint Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Analysis of Questionnaire Survey

4.2.1. Children and Their Parents (Questionnaire A)

4.2.2. Hospital (Questionnaire B)

4.2.3. Five Dimensions That Affect Children’s Medical Service Experiences

4.3. Descriptive Analysis of Questionnaire Survey

4.3.1. The Weight of Each Dimension

4.3.2. Satisfaction Calculation and Analysis Based on the Weight of Each Dimension and Questionnaire Score

4.4. Principal Component Analysis of Questionnaire Survey Data

- Standardize the data: use each element to subtract the average value of each element’s score. Then, divide by the standard deviation to ensure that each element is statistically comparable.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient matrix: conduct a correlation analysis between each element and the other elements to obtain a 5 × 5 correlation coefficient matrix. On the diagonal of this matrix is each element’s own variance.

- Perform eigenvalue decomposition: decompose the correlation coefficient matrix into eigenvectors and eigenvalues. The eigenvectors describe the principal directions of the dataset. The eigenvalues represent the variance in each direction. Since the eigenvectors are unit vectors, their sum of squares is 1.

- Select the number of factors: determine the number of factors to retain based on the eigenvalues. In general, studies select factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 because they explain the dataset better.

- Calculation of factor loading coefficient and commonality: the factor loading coefficient represents the proportion of each variable in each factor. The degree of commonality refers to the proportion of variance that each variable can be explained via common factors. By analyzing these, one can determine what each factor represents and which variables are most correlated with which factors.

- Named factors: according to the loading coefficient and commonality of each factor, the significance represented by each factor can be determined and named. Naming can be numbered with letters or numbers. For example, the variables with a high-loading coefficient of factor A1 include “waiting time”, “comfort of medical treatment place”, “friendliness of doctor’s attitude”, and “completeness of medical facilities”. Therefore, this factor could be named “waiting environment and information flow”. It represents a common theme described by these variables. By naming the factors, this study can better understand the potential factors in the dataset, making it easier to explain and apply them. Through the analysis of this factor, the improvement in the patient’s medical experience and satisfaction can be achieved.

4.4.1. Questionnaire A Principal Component Analysis

- Waiting dimension.

- 2.

- Waiting Facilities Dimension

- 3.

- Outpatient Appointment Dimension.

- 4.

- Outpatient Management System Dimension

- 5.

- Outpatient Visiting Process Dimension

4.4.2. Questionnaire B Principal Component Analysis

- Waiting Facilities Dimension

- 2.

- Waiting Dimension

- 3.

- Outpatient appointment dimension

- 4.

- Outpatient Management System Dimension

- 5.

- Outpatient Visiting Process Dimension

4.5. Structured Interview Analysis

- Respondents brainstormed on a topic describing their experience with pediatric patients during outpatient care in the hospital.

- All questions were recorded in notes and categorized according to the topics raised during the brainstorming session.

- Simultaneously, the researcher observed and took notes on the activities of the participants. These notes were recorded and organized while reviewing the video after the meeting.

- After the interview, the interview content was combined with the observer’s notes and categorized by theme in order to analyze the large amount of unstructured oral content.

- Through the questions posed by the interviewers, the research aggregated keywords and grouped them to form themes for strategy formulation. Based on these themes, all interview participants jointly developed goals for improving the pediatric outpatient experience and strategies for addressing each goal.

4.5.1. Interview Results

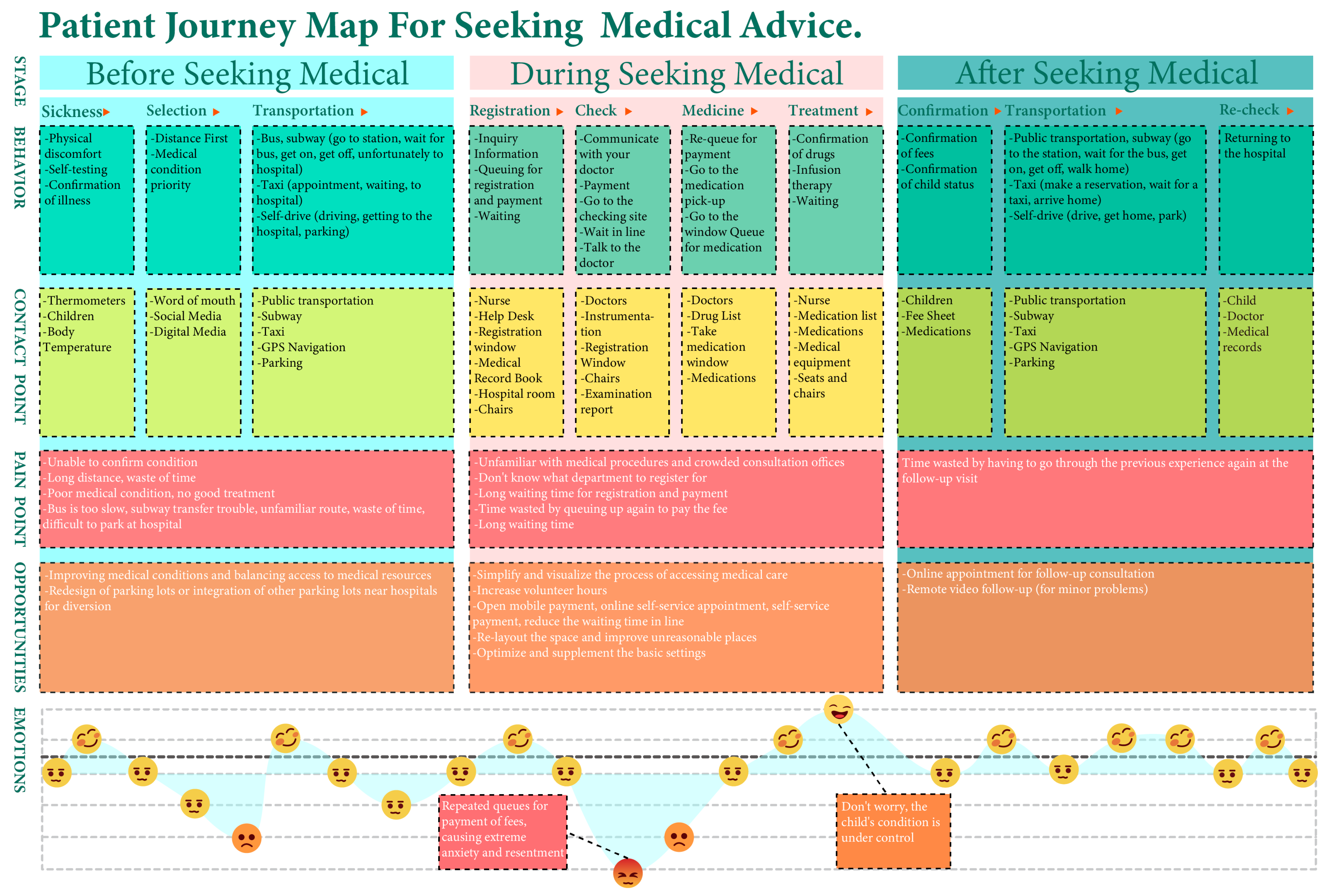

4.5.2. User Journey Map

4.6. Summary of Influencing Elements

- Preliminary field investigation and analysis summary: outpatient procedures are complicated, child patients have to queue throughout all aspects of treatment, child patients are emotionally uneasy during the waiting process, short times for medical treatment leads to an inability to communicate effectively with doctors, communication barriers between doctors and patients, insufficient nursing services, and insufficient drug reserves.

- Summary of questionnaire descriptive analysis: the improvement of outpatient facilities, the comfort level of waiting area, waiting time for consultation, outpatient efficiency based on digital system, medical care service, doctor–patient communication.

- Questionnaire satisfaction analysis and dimension weight summary: waiting facilities dimension, outpatient management system dimension, outpatient queuing appointment dimension, outpatient visiting process dimension, and waiting dimension.

- Summary of principal component analysis of the questionnaire: waiting dimension (waiting time, the speed of diagnosis and treatment, and cost), waiting facilities dimension (environmental comfort, facility comprehensiveness, convenience, informatization level, and facility service quality), outpatient appointment dimension (appointment experience, medical staff appointment service attitude and fairness, epidemic-related issues, appointment information guidelines, and appointment process), outpatient management dimensions (convenient medical treatment and service quality), outpatient visiting process dimensions (visit efficiency, visit process information sharing and appointment convenience, flexible ways of seeing a doctor, the orientation of the visit process, and the convenience of the visit process).

5. Discussion

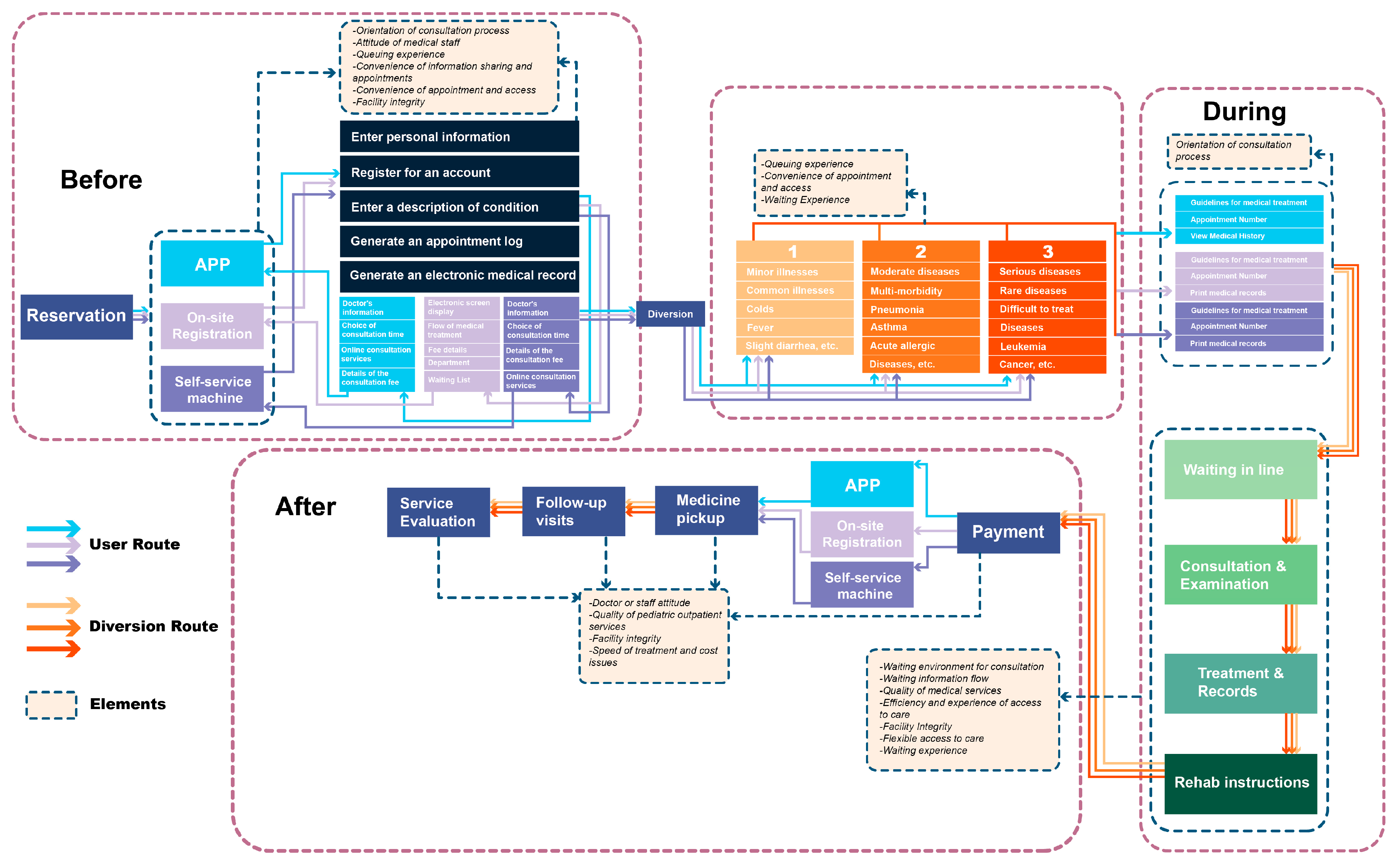

5.1. Children’s Outpatient Medical Services Node Improvement Plan Based on Influencing Elements

5.2. Systematic Conception of Strategy Model Based on Element Analysis

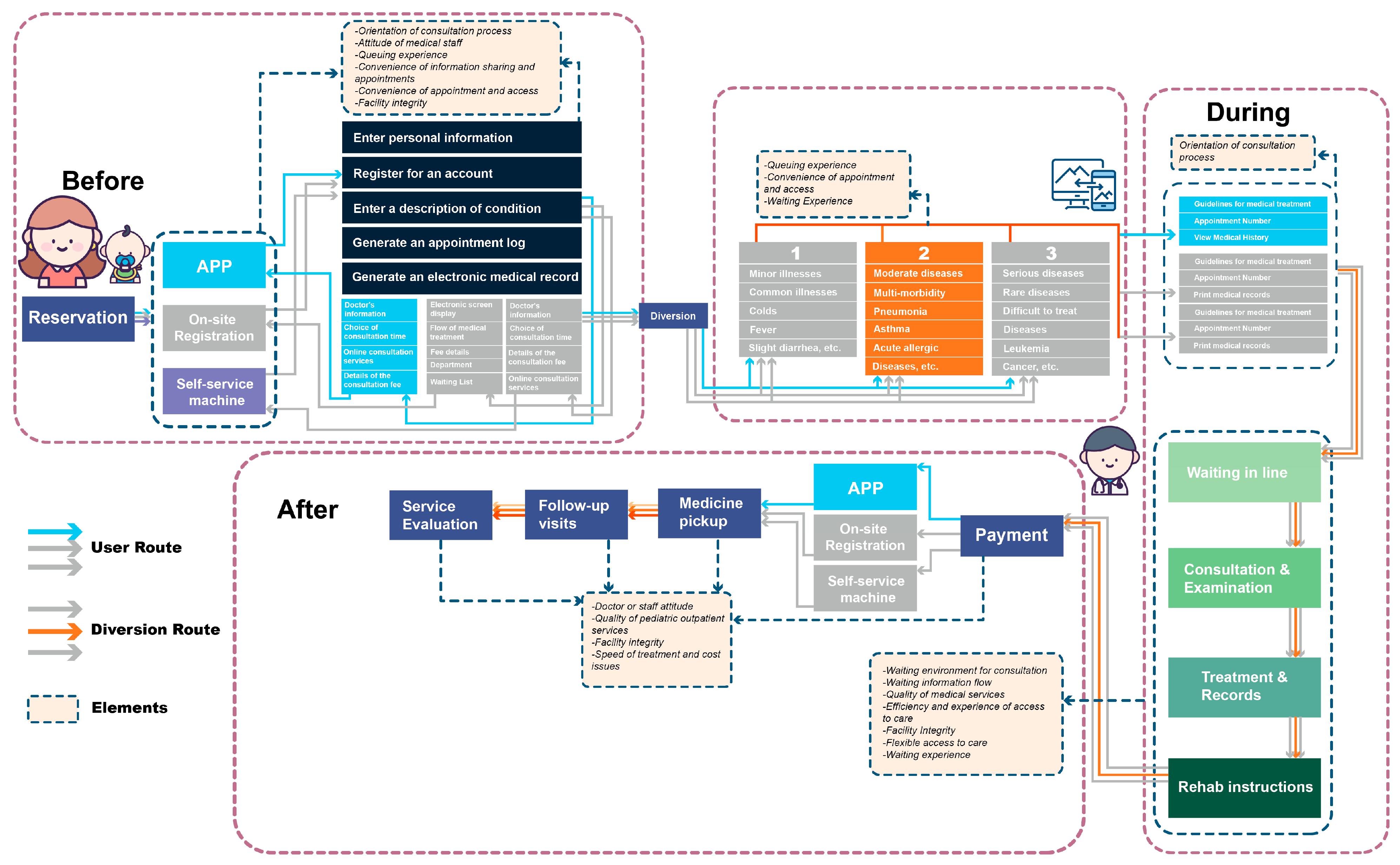

5.3. A Model of Healthcare Delivery Strategies for Improving Children’s Medical Service Experiences

5.3.1. Before Seeing a Doctor

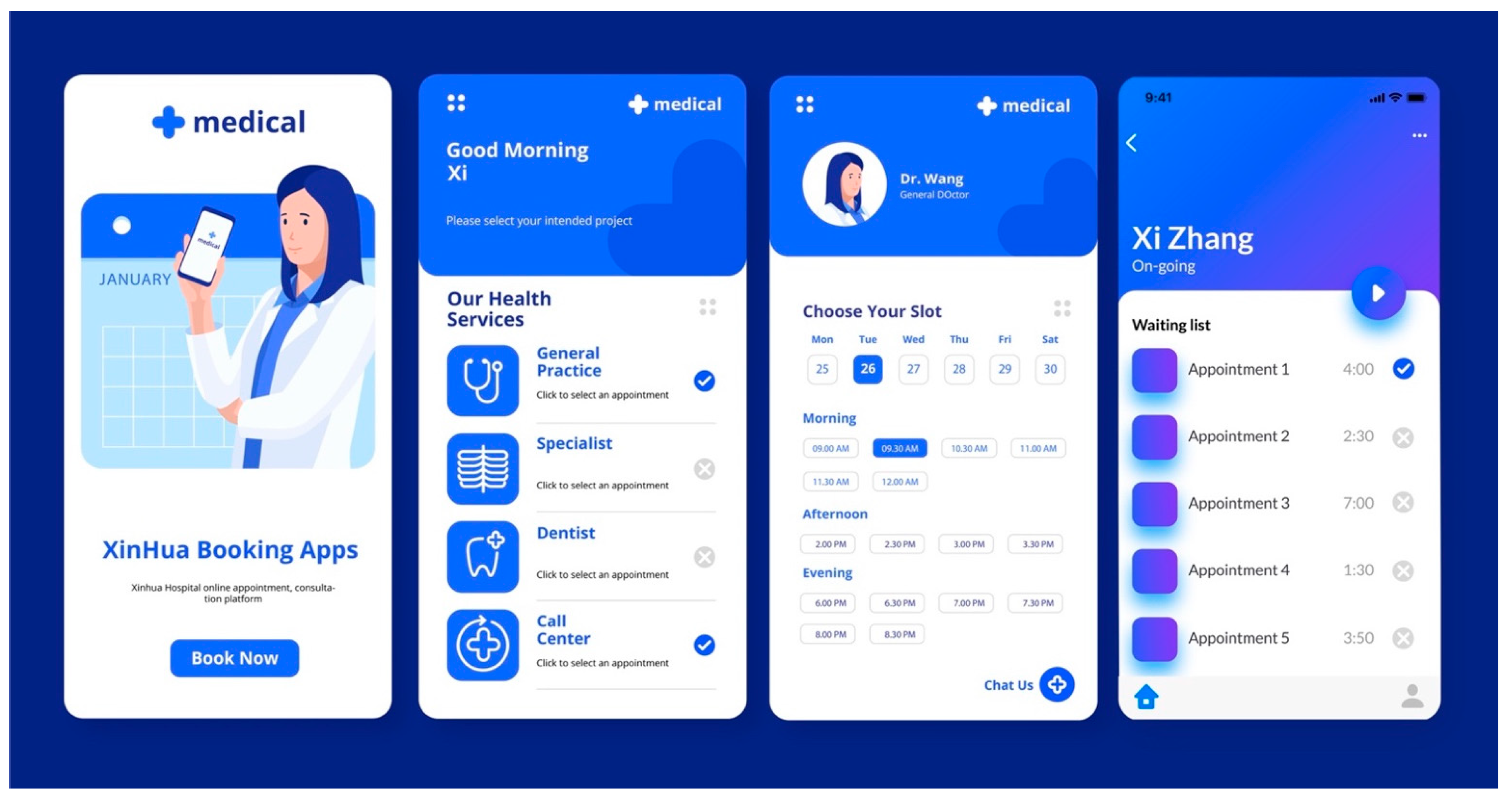

- Step 1: Appointment for medical treatment

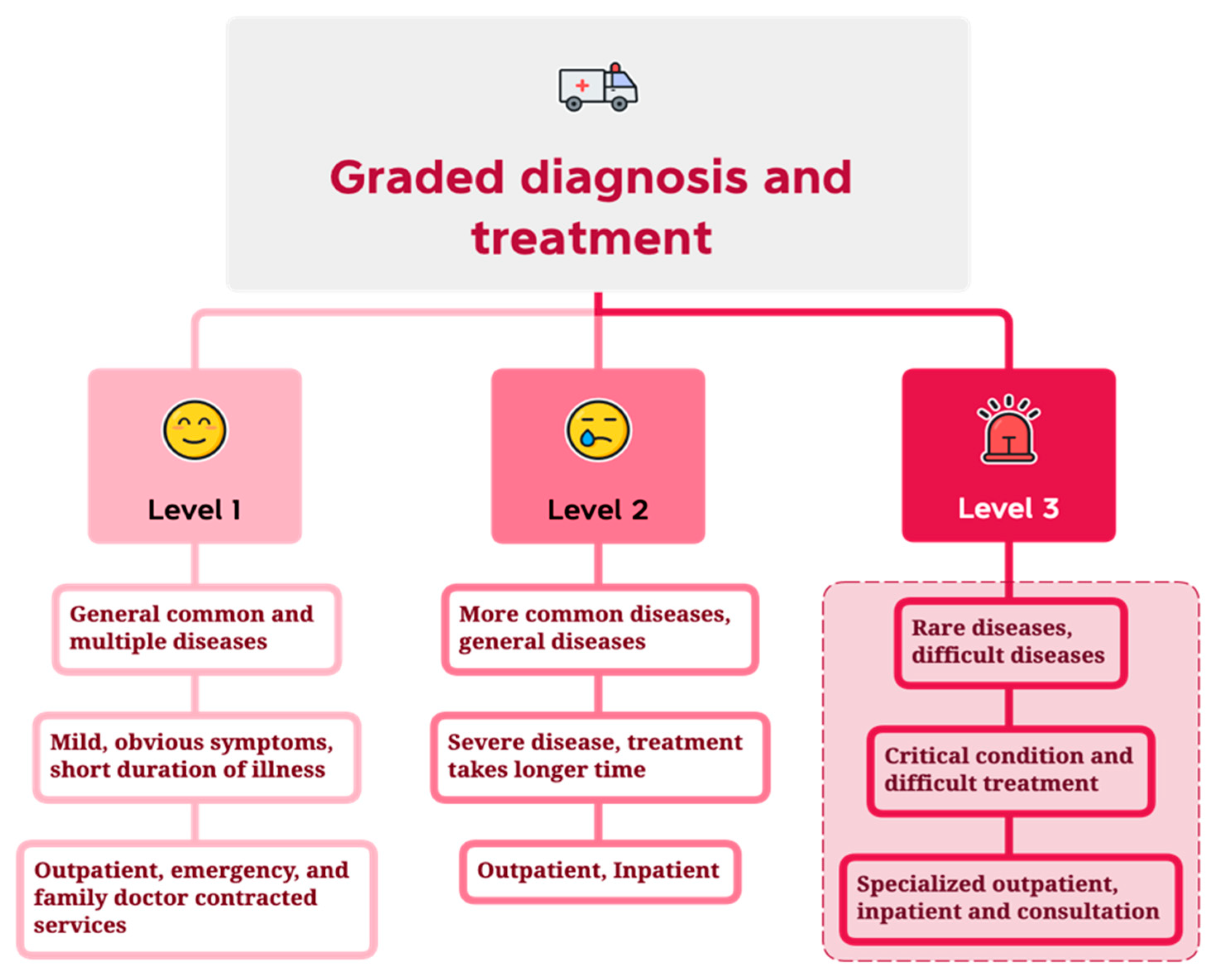

- Method A: Utilize the Xinhua Hospital app to make an appointment online. The patient registers an account on the application (app), enters the description of the condition, and generates an electronic medical record and appointment record. The app can provide information such as doctor’s information, choice of visit time, details of visit expenses, etc. This can help users to better understand medical services. The app uses AI technology to automatically judge the patient’s condition and classify it (level 1, level 2, and level 3 diseases). Then, the app can give appointment recommendations for various departments and the relevant doctor’s working hours and dates in order to allow patients to make the choices. At the same time, the app can also provide manual online consultation services. After completing the above process, the app can give patients an appointment number and guide the treatment process in order to help the patient arrive at the hospital for diagnosis and treatment according to the appointment time. This can effectively prevent patients from waiting in long queues in the outpatient hall. The app conceptual design scheme is shown in Figure 10.

- Method B: Make an appointment at the manual registration window. When the patient arrives at the hospital, they will queue up for registration at the manual registration window in the outpatient hall. The electronic screen of the registration window can display the registration process guidelines, cost details, types of departments and the number of people waiting in order to guide patients to see a doctor in an orderly manner and avoid chaotic and disorderly queuing conditions. The medical staff in the artificial window will enter the symptoms described by the patients into the system. The system generates case records based on the entered patient information and uses AI technology to automatically determine illness level (level 1, level 2, and level 3). Then, AI can make an appointment registration according to the relevant doctor’s work schedule and timetable on that day and generate an appointment number. Finally, the patient will go to the doctor’s department for consultation according to the guidance of the treatment process and the patient’s medical record information file provided by the outpatient window.

- Method C: Make an appointment at the self-service machine in the outpatient hall. The patient arrives at the hospital, enters personal information on the self-service machine, enters a description of the condition, and generates an electronic medical record and appointment record. Self-service machines can provide information about doctors, possible visiting times, details of visit expenses, etc., to help users better understand medical services. The other processes of the self-service machine system are the same as those of the manual registration window, the difference is that the service is provided by the self-service machine.

- 2.

- Step 2: Patient Triage

5.3.2. Whilst Seeing a Doctor

- Step 1: Waiting in line for treatment

- 2.

- Step 2: Inquiry and examination

- 3.

- Step 3: Diagnosis and Treatment and Medical Records

- 4.

- Step 4: Rehabilitation command

- Doctors and nurses making rounds: Regularly inspect the waiting area of the level 3 area, check the patient’s physical condition, identify the progress of the disease, and adjust the treatment plan in time.

- Professional nursing: Provide professional nursing services for patients, such as infusion, wound care, vital signs monitoring, etc.

- Disease knowledge and education: provide publicity and education services for patients’ diseases and help patients understand the causes, symptoms, treatment methods, and preventive measures of diseases.

- Social work services: Provide social work services to help patients solve life, economic, psychological, and other problems that may be encountered during medical treatment.

- Psychological counseling: Provide psychological counseling services to help patients alleviate negative emotions such as anxiety and fear, adjust their mentality, and enhance their disease resistance.

5.3.3. After Seeing a Doctor

- Step 1: Pay for medicine.

- Method 1: Xinhua Hospital app payment. Patients pay according to the drug list prescribed by the doctor and go to the pharmacy to pick up the medicine.

- Method 2: Pay at the payment window of the pharmacy and pick up the medicine. When patients go to the pharmacy to queue, the doctor will use the system to make an appointment for the patient to take a number in advance and inform the pharmacy to arrange and pack the medicines in advance, so that the patients can receive their medication directly when they arrive at the pharmacy. This prevents long queues and improves the efficiency of the pharmacy.

- Method 3: Pay for and collect medicine at the pharmacy self-service machine. After paying at the self-service machine in the pharmacy, the patient goes directly to the window to pick up the medicine.

- Method 4: Purchase medication at pharmacies by themselves. Patients go to the hospital pharmacy or a cooperative pharmacy to purchase and collect medicines by themselves and receive the prescribed medicines issued by doctors.

- 2.

- Step 2: Follow-up.

- 3.

- Step 3: Evaluation of medical services.

5.4. Strategy Model Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Questions | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Waiting dimension | Is the time you wait before seeing a doctor reasonable? | 1–5 points |

| Waiting facilities dimension | Do you think the facilities in the waiting area are comfortable and safe? | 1–5 points |

| Outpatient queuing appointment dimension | Is the time you wait in the waiting queue reasonable? | 1–5 points |

| Outpatient management system | Do you think the hospital’s queuing management for children’s outpatient clinics is reasonable? | 1–5 points |

| Outpatient visiting process dimension | Do you feel that the service attitude of the medical staff is good during the consultation process? | 1–5 points |

Appendix B

| Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is your experience at the pediatric outpatient department of Xinhua Hospital? |

| 2 | Do you think the hospital’s workflow and processes need to be improved to better meet the needs of children and parents? |

| 3 | Do you have any suggestions to improve the comfort and service quality of the outpatient waiting area? |

| 4 | Do you think it is important to provide sufficient facilities and humanitarian care for children and special needs patients in the outpatient department? |

| 5 | What are the issues in regard to the inconvenience of seeking medical treatment in the hospital? What are the issues that affect the experience? |

| 6 | What are your suggestions for improving the quality of medical services in hospitals? |

| 7 | Do you support the hospital to introduce a more effective AI access management system to improve the efficiency of outpatient management? |

| 8 | Do you think hospitals should establish a hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system and hierarchical diagnosis and treatment department management? If so, what suggestions do you have? |

| 9 | Do you think the hospital’s information technology systems (such as medical record systems, medical equipment, etc.) are sufficiently advanced and convenient? If not, please list the areas you believe need improvement. |

| 10 | If the maximum score is 10, how would you rate the current medical services provided by the pediatric outpatient department of Xinhua Hospital? |

References

- Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Yao, P. A study on the efficiency of pediatric healthcare services and its influencing factors in China—Estimation of a three-stage DEA model based on provincial-level data. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 84, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Lu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effective multidimensional approach for practical management of the emergency department in a COVID-19 designated children’s hospital in east China during the Omicron pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M. Will China’s nutrition transition overwhelm its health care system and slow economic growth? Health Aff. 2008, 27, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerall, C.; Cheung, E.W.; Klein-Cloud, R.; Kreines, E.; Brewer, M.; Middlesworth, W. Allocation of resources and development of guidelines for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): Experience from a pediatric center in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 2548–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Vinkers, C.H.; et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, E.S. Art Is Fun, Art Is Serious Business, and Everything in between: Learning from Art Therapy Research and Practice with Children and Teens. Children 2022, 9, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Reda, S.; Martin, S.; Long, P.; Franklin, A.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Wiener, L.; Wolters, P.L. The needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic illness: Results of a quality improvement survey. Children 2022, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buka, S.S.L.; Beers, L.S.; Biel, M.G.; Counts, J.N.Z.; Hudziak, J.; Parade, S.H.; Paris, R.; Seifer, R.; Drury, S.S. The family is the patient: Promoting early childhood mental health in pediatric care. Pediatrics 2022, 149 (Suppl. S5), e2021053509L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, G.; Yang, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Yang, J. Experiences and Challenges of Implementing Universal Health Coverage with China’s National Basic Public Health Service Program: Literature Review, Regression Analysis, and Insider Interviews. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e31289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskey, A.; Haney, S.; Northrop, S.; Council On Child Abuse And Neglect. Protecting children from sexual abuse by health care professionals and in the health care setting. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022058879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L.; Ni, X. Causes of hospital violence, characteristics of perpetrators, and prevention and control measures: A case analysis of 341 serious hospital violence incidents in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Wang, P. Has China’s healthcare reform reduced the number of patients in large general hospitals? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Han, H.; Du, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y. Clinical features and outcomes of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis in children: A retrospective analysis of 26 cases in China. Neuropediatrics 2022, 53, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhou, S.; Hunt, K.; Zhuang, J. Comprehensive evolution analysis of public perceptions related to pediatric care: A sina Weibo case study (2013–2020). SAGE Open 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Guo, R.; Hu, X.; Qi, Z.; Guo, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; et al. Newborn screening with targeted sequencing: A multicenter investigation and a pilot clinical study in China. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Yao, P. Assessing the financial efficiency of healthcare services and its influencing factors of financial development: Fresh evidences from three-stage DEA model based on Chinese provincial level data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 21955–21967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, L.; Hu, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, M.; Huang, L.; Jin, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, J. Using the Delphi method to establish pediatric emergency triage criteria in a grade A tertiary women’s and children’s hospital in China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Jiang, H.; Mossialos, E.; Chen, W. Improving access to medicines: Lessons from 10 years of drug reforms in China, 2009–2020. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, P.; Nie, M.; Gao, K.; Yang, J.; Sun, J. Changes of Haemophilus influenzae infection in children before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, Henan, China. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 66–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Z.-E.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wei, H.; Hua, Z. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neonatal admissions in a tertiary children’s hospital in southwest China: An interrupted time-series study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, T. Biophilic Design as an Important Bridge for Sustainable Interaction between Humans and the Environment: Based on Practice in Chinese Healthcare Space. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8184534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Lee, M. Automatic design and optimization of educational space for autistic children based on deep neural network and affordance theory. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Lv, Z. Human-centered intelligent healthcare: Explore how to apply AI to assess cognitive health. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2022, 4, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whear, R.; Abbott, R.A.; Bethel, A.; Richards, D.A.; Garside, R.; Cockcroft, E.; Iles-Smith, H.; Logan, P.A.; Rafferty, A.M.; Thompson Coon, J.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 and other infectious conditions requiring isolation on the provision of and adaptations to fundamental nursing care in hospital in terms of overall patient experience, care quality, functional ability, and treatment outcomes: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 78–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, T.I.; Zerbe, A.; Falcao, J.; Carey, S.; Iaccarino, A.; Kolada, B.; Olmedo, B.; Shadwick, C.; Singhal, H.; Weinstein, L.; et al. Human-Centered Design for Public Health Innovation: Codesigning a Multicomponent Intervention to Support Youth Across the HIV Care Continuum in Mozambique. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, N.L.; Nieman, C.L.; Coco, L. Community-based participatory research and human-centered design principles to advance hearing health equity. Ear Hear. 2022, 43 (Suppl. S1), 33S–44S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, D.Z.; Rodgers, R.C.; Beers, N.S.; McLellan, S.E.; Nguyen, T.K. Access to services for children and youth with special health care needs and their families: Concepts and considerations for an integrated systems redesign. Pediatrics 2022, 149 (Suppl. S7), e2021056150H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenfield, S.J.; Awad, A.; McCoubrey, L.E.; Elbadawi, M.; Goyanes, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Advancing pharmacy and healthcare with virtual digital technologies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 182, 114098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, J.S.; Landman, A.B.; Brat, G.A.; Dunn, T.; Gordon, W.J. Deploying digital health tools within large, complex health systems: Key considerations for adoption and implementation. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoloni, S.; Calò, E.; Marinelli, L.; Pascucci, F.; Dezi, L.; Carayannis, E.; Revel, G.M.; Gregori, G.L. Towards designing society 5.0 solutions: The new Quintuple Helix-Design Thinking approach to technology. Technovation 2022, 113, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.; Lang, S.; Truby, H.; Brennan, L.; Gibson, S. Tackling the challenge of treating obesity using design research methods: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettel, C.J.; Serina, P.T.; Uzamere, I.; Hernandez-Bigos, K.; Venkatesh, A.K.; Rising, K.L.; Goldberg, E.M.; Feder, S.L.; Cohen, A.B.; Hwang, U.; et al. Emergency department-to-community care transition barriers: A qualitative study of older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 3152–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanbach, D.; Dickinson, J.I.; Cline, H.; Sullivan, K. Photography & Art Creation to Address Anticipatory Grief: A Design Thinking Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Radford University, Radford, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, B.; Lupton, E. Health Design Thinking: Creating Products and Services for Better Health; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, M.J. Fiftieth anniversary of uncovering the tuskegee syphilis study: The story and timeless lessons. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, S.; Sendak, M.P.; Ratliff, W.; Knechtle, W.; Fulkerson, W.J.; Balu, S. Accelerating Health System innovation: Principles and practices from the Duke Institute for Health Innovation. Patterns 2023, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, M.K.; Salcedo, V.J.; Hsiao, T.; Esteves Camacho, T.; Salvatore, A.; Siegler, A.; Rising, K.L. Pilot testing fentanyl test strip distribution in an emergency department setting: Experiences, lessons learned, and suggestions from staff. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 30, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorheis, P.; Zhao, A.; Kuluski, K.; Pham, Q.; Scott, T.; Sztur, P.; Khanna, N.; Ibrahim, M.; Petch, J. Integrating behavioral science and design thinking to develop mobile health interventions: Systematic scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e35799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitsaras, G.; Asimakopoulou, K.; Henshaw, M.; Borrelli, B. Theoretical and methodological approaches in designing, developing, and delivering interventions for oral health behaviour change. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2023, 51, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.; Cacchione, P.Z.; Demiris, G.; Carthon, J.M.B.; Bauermeister, J.A. An integrative review of human-centered design and design thinking for the creation of health interventions. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn-Goldberg, S.; Chaput, A.; Rosenberg-Yunger, Z.; Lunsky, Y.; Okrainec, K.; Guilcher, S.; Ransom, M.; McCarthy, L. Tool development to improve medication information transfer to patients during transitions of care: A participatory action research and design thinking methodology approach. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; Yang, M. Beyond Design Thinking: Exploring Design Modes for Children’s Medical Care Service and Experience. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Computer Technology and Media Convergence Design (CTMCD 2022), Dali, China, 13–15 May 2022; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 519–527. [Google Scholar]

- Saurio, R.; Hennala, L.; Pekkarinen, S.; Melkas, H. Design Thinking and Welfare: A Focus on Information Design. In Different Perspectives in Design Thinking; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 165–201. [Google Scholar]

- Frolic, A.; Murray, L.; Swinton, M.; Miller, P. Getting beyond pros and cons: Results of a stakeholder needs assessment on physician assisted dying in the hospital setting. In Hec Forum; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, J.D.; Wolpaw, D.R.; Cooney, R.; Mazotti, L.; Reilly, J.B.; Wolpaw, T. Evolving the systems-based practice competency in graduate medical education to meet patient needs in the 21st-century health care system. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Pasha, M.F.; Fang, O.H.; Khan, R.; Teo, J.; Zakarya, M. An industrial IoT-based blockchain-enabled secure searchable encryption approach for healthcare systems using neural network. Sensors 2022, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, A.J. The biopsychosociotechnical model: A systems-based framework for human-centered health improvement. Health Syst. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.M.; Brownson, R.C.; Glasgow, R.E.; Morrato, E.H.; Luke, D.A. Designing for dissemination and sustainability to promote equitable impacts on health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Tao, Y. Associations between spatial access to medical facilities and health-seeking behaviors: A mixed geographically weighted regression analysis in Shanghai, China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 139, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Lu, C.; Gao, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, G. Health-related quality of life and related factors among primary caregivers of children with disabilities in shanghai, china: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Tang, L.; Gui, Y.; Ye, Y.; Gu, D.; Feng, R.; Zhang, X. Description of the medical services provided to children in Shanghai: A cross-sectional study of the characteristics and disparities of hospitals of different levels and types. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleni, M.T. Real-life practice of the Egyptian Kelleni’s protocol in the current tripledemic: COVID-19, RSV and influenza. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 154–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Long, Y.; Greenhalgh, C.; Steeg, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Li, H.; Verma, A.; Spencer, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors associated with healthcare-associated infections among hospitalised patients in Chinese general hospitals from 2001 to 2022. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 135, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Ke, Z.; Wang, Z.; Pan, J.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Sun, K.; et al. Characteristics and workload of pediatricians in China. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Shaw, R. Corona virus (COVID-19) “infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byttebier, K. COVID-19 and the Sector of the Long-Term Nursing Homes. In COVID-19 and Capitalism: Success and Failure of the Legal Methods for Dealing with a Pandemic; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 589–661. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, R.; Feng, R.; Zhou, Y.; Hong, J.; Cao, L.; Lu, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Size-segregated particle number concentrations and outpatient-department visits for pediatric respiratory diseases in Shanghai, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 243, 113998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, W. The clinical characteristics and serological outcomes of infants with confirmed or suspected congenital syphilis in Shanghai, China: A hospital-based study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chang, H.; Tian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, A.; Ge, Y.; Zeng, M.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children during the outbreak of Omicron variant in Shanghai, March 7–31, 2022. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2022, 16, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wu, Y.F.; Chen, Y.W.; Fang, X.Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Q. Clinical characteristics of pediatric cases infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in a tertiary children’s medical center in Shanghai, China. World J. Pediatr. 2023, 19, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Kong, W.; Lu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gan, L.; Tang, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. Epidemiological and clinical features of paediatric inpatients for scars: A retrospective study. Burns, 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Cheng, F.; Gao, X.; Yu, W.; Shi, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-D.; et al. Hospital crowdedness evaluation and in-hospital resource allocation based on image recognition technology. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Fu, J.; Zeng, M.; Ge, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, A.; Shen, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Jiang, S.; et al. Information technology and artificial intelligence support in management experiences of the pediatric designated hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic in 2022 in Shanghai. Intell. Med. 2023, 3, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. Effectiveness and safety of Daixie Decoction granules combined with metformin for the treatment of T2DM patients with obesity: Study protocol for a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicentre clinical trial. Trials 2023, 24, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y. Online Dialogue with Medical Professionals: An Empirical Study of an Online’Ask the Doctor’Platform. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Filip, R.; Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Dimian, M.; Savage, W.K. Global Challenges to Public Health Care Systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Pandemic Measures and Problems. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Xi, X. Capturing What Matters with Patients’ Bypass Behavior? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, D.; Xiao, Y.; Song, K.; Dong, M.; Li, L.; Millar, R.; Shi, C.; Li, G. Determinants Influencing the Adoption of Internet Health Care Technology Among Chinese Health Care Professionals: Extension of the Value-Based Adoption Model with Burnout Theory. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e37671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, J.; Li, S.; Wu, M.; Yan, C.; Yu, G.; Hu, Y.; et al. Association of childhood asthma with intra-day and inter-day temperature variability in Shanghai, China. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, I.; Schoffer, O.; Richter, T.; Kiess, W.; Flemming, G.; Winkler, U.; Quietzsch, J.; Wenzel, O.; Zurek, M.; Manuwald, U.; et al. Current and projected incidence trends of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Germany based on the Saxon Pediatric IBD Registry 2000–2014—A 15-year evaluation of trends. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.; Atyah, M.M.; Ren, N. The Regionalization of medical management: The practice and exploration of established Fudan-Minhang medical alliance. In Regionalized Management of Medicine; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, M.; Huang, Z.; Ren, J.; Wagner, A.L. Vaccine hesitancy and receipt of mandatory and optional pediatric vaccines in Shanghai, China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2043025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Y.; Xu, L.; Wei, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Increased anxiety and stress-related visits to the Shanghai psychiatric emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 compared to 2018–2019. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1146277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, P.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Hao, M.; et al. Impact of new health care reform on enabling environment for children’s health in China: An interrupted time-series study. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 11002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gahr, M.; Xiang, Y.; Kingdon, D.; Rüsch, N.; Wang, G. The state of mental health care in China. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 69, 102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Guo, J. China’s social assistance and poverty reduction policy: Development, main measures, and inspiration to global poverty alleviation. Razón Crítica 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gu, Q.; Li, C.; Huang, Y. Characteristics and spatial–temporal differences of urban “production, living and ecological” environmental quality in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Liao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X. Effects of Healthcare Policies and Reforms at the Primary Level in China: From the Evidence of Shenzhen Primary Care Reforms from 2018 to 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, W.; Fan, Y.; Leng, Y.; Gao, C. Establishment and effectiveness evaluation of a scoring system-RAAS (RDW, AGE, APACHE II, SOFA) for sepsis by a retrospective analysis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Rozanova, L.; Fabre, G. COVID-19 and Internet Hospital Development in China. Epidemiologia 2022, 3, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Zahid, K.R.; Han, Y.; Hu, P.; Zhang, D. Treatment of Pediatric Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor: The Experience from China Children’s Medical Center. Children 2022, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, W.; Duan, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, B.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Oxidative Stress-Mediated Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 1569–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Zeng, J.; Sun, J.; Ye, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L.; Song, L. Lung-specific exosomes for co-delivery of CD47 blockade and cisplatin for the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 2723–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yang, L.; Yan, W.; Yu, Q.; Sheng, J.; Mao, X.; Feng, Y.; Tang, Q.; Cai, W.; et al. Evaluation of a new digital pediatric malnutrition risk screening tool for hospitalized children with congenital heart disease. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pi, D.D.; Liu, C.J.; Li, J.; Xu, F. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic among healthcare workers in paediatric intensive care units in China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Wang, X.-R.; Jiao, X.-T.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.-L.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.-D. Maternal and neonatal blood vitamin D status and neurodevelopment at 24 months of age: A prospective birth cohort study. World J. Pediatr. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Vertinsky, I. Providing and Health Medicines Access to Affordable Care for Global Health Security in China, Japan, and India: Assessing Sustainable Development Goals; UBC Press: Vancouver, Canada, 2023; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Xia, H. How Advanced Practice Nurses Can Be Better Managed in Hospitals: A Multi-Case Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Gu, H.; Li, M.; Chen, R.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Y. Air pollution and weather conditions are associated with daily outpatient visits of atopic dermatitis in Shanghai, China. Dermatology 2022, 238, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Gu, D.; Yu, F.; Li, Q. Social distancing cut down the prevalence of acute otitis media in children. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1079263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yuan, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lv, G.; Lin, S.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Tang, M.; et al. SPRSound: Open-Source SJTU Paediatric Respiratory Sound Database. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Tan, J.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Wu, M.; Yan, C.; Yu, G.; Hu, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. Environmental exposure and childhood atopic dermatitis in Shanghai: A season-stratified time-series analysis. Dermatology 2022, 238, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Bai, J.; Feng, R. Evaluating the spatial accessibility of medical resources taking into account the residents’ choice behavior of outpatient and inpatient medical treatment. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Shaw, R. Technology Landscape in Post COVID-19 Era: Example from China. In Society 5.0, Digital Transformation and Disasters: Past, Present and Future; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 163–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, F.; Qian, H.; Lei, J.; Ni, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Ding, K. Experiences and challenges of emerging online health services combating COVID-19 in China: Retrospective, cross-sectional study of internet hospitals. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e37042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhan, J.; Cheng, T.; Fu, H.; Yip, W. Understanding online dual practice of public hospital doctors in China: A mixed-methods study. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, T.; Schmidt, A.E.; Bobek, J.; Ladurner, J. Barriers to accessing health care for people with chronic conditions: A qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negasi, K.B.; Tefera Gonete, A.; Getachew, M.; Assimamaw, N.T.; Terefe, B. Length of stay in the emergency department and its associated factors among pediatric patients attending Wolaita Sodo University Teaching and Referral Hospital, Southern, Ethiopia. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogeler, C.S.; van den Dool, A.; Chen, M. Programmatic action in Chinese health policy—The making and design of “Healthy China 2030”. Rev. Policy Res. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G. Taking Responsibility for Your Own Health: Understanding Chinese Health Television. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Xie, J.; Hu, J.; Zhu, D.; Wang, D. Willingness to engage in post-discharge follow-up service conducted via video telemedicine: Cross-sectional study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 168, 104885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Han, X.; Xi, T. The Design of Outpatient Services in Children’s Hospitals Based on the Double Diamond Model. In Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management. AI, Product and Service: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, DHM 2021, Held as Part of the 23rd HCI International Conference, HCII 2021, Virtual Event, 24–29 July 2021, Part II.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, K.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhang, W. Evaluation of droplet digital PCR rapid detection method and precise diagnosis and treatment for suspected sepsis (PROGRESS): A study protocol for a multi-center pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Li, N.; Kong, N.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, X. Optimal Two-Tier Outpatient Care Network Redesign With a Real-World Case Study of Shanghai. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijindu Ukagwu, R.N.; Seth Gray, M.D. Applying the principles of Design Thinking to the Intensive Care Environment. UTMJ 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interaction Design Foundation; Dam, R.F.; Siang, T.Y. What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular? 2021. Available online: https://athena.ecs.csus.edu/~buckley/CSc170_F2018_files/What%20is%20Design%20Thinking%20and%20Why%20Is%20It%20So%20Popular.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A.; Alyahya, S.A.; Alshehri, R.; Alqadi, K.; Alasmari, S. Using Design Thinking Principles to Improve Outpatients’ Experiences in Hospital Pharmacies: A Case Study of Two Hospitals in Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2021, 9, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, N.; Jones, C.R.; Pittman, B.R.; Purter, T.; Russell, M.; Brown, J.; Ladores, S. Applying design thinking in health care: Reflections of nursing honors program students. Creat. Nurs. 2020, 26, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thienprayoon, R.; Hauer, J.; Lord, B.; Siedman, J.; Anthony, M. Creating a “journey map” for children with severe neurologic impairment: A collaboration between private and academic pediatric palliative care, non-profit organizations, and parents (TH127). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Hands, D. Design Thinking: Practice and Applications. In Design Thinking for New Business Contexts: A Critical Analysis through Theory and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, E.M.; van der Cruyssen, L.; Vágó, S.; Király, G.; Arbour, T.; van Dijk, L. Designing for agricultural digital knowledge exchange: Applying a user-centred design approach to understand the needs of users. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Mulisa, F. When Does a Researcher Choose a Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed Research Approach? Interchange 2022, 53, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Brown, S.A.; Zhao, T. Understanding users’ trust transfer mechanism in a blockchain-enabled platform: A mixed methods study. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 155, 113716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C.; Livia-Segovia, J. Calificación promedio de jueces expertos e intervalos de confianza asimétricos en la validez de contenido: Una sintaxis SPSS. An. Psicol. 2022, 38, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesher Shoshan, H.; Wehrt, W. Understanding “Zoom fatigue”: A mixed-method approach. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 827–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Gonçalves, H.M. Consumer decision journey: Mapping with real-time longitudinal online and offline touchpoint data. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.M.; Shrivastav, S. Service Design Approach to Elevate the Patient Experience during Home X-Rays. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, C.; Lauret, J.; Drouet, L. Physical Journey Maps: Staging Users’ Experiences to Increase Stakeholders’ Empathy towards Users. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, J.P. Data Analysis in Management with SPSS Software; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Yang, W.; Sun, S. Analysis of the impact of China’s hierarchical medical system and online appointment diagnosis system on the sustainable development of public health: A case study of Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Age | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | under 25 | 67 | 18.2% |

| 25–35 | 123 | 33.4% | |

| 35–45 | 97 | 26.3% | |

| over 45 | 81 | 22.1% | |

| Subtotal: 368 | 46% | ||

| Female | under 25 | 117 | 27.2% |

| 25–35 | 179 | 41.4% | |

| 35–45 | 72 | 16.6% | |

| over 45 | 64 | 14.8% | |

| Subtotal: 432 | 54% | ||

| Total | 800 | 100.00% |

| Gender | Age | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man | under 25 | 7 | 6.4% |

| 25–35 | 18 | 16.5% | |

| 35–45 | 63 | 57.7% | |

| over 45 | 21 | 19.2% | |

| Subtotal: 109 | 54.5% | ||

| Woman | under 25 | 14 | 15.3% |

| 25–35 | 37 | 40.7% | |

| 35–45 | 22 | 24.2% | |

| over 45 | 18 | 19.8% | |

| Subtotal: 91 | 45.5% | ||

| Total | 200 | 100.00% |

| Gender | Age | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man | under 25 | 38 | 5.66% |

| 25–35 | 150 | 17.70% | |

| 35–45 | 169 | 41.84% | |

| over 45 | 113 | 13.32% | |

| Subtotal: 470 | 78.52% | ||

| Woman | under 25 | 42 | 11.11% |

| 25–35 | 137 | 36.24% | |

| 35–45 | 170 | 44.97% | |

| over 45 | 29 | 7.67% | |

| Subtotal: 378 | 44.57% | ||

| Total | 848 | 100.00% |

| Gender | Age | Number of People | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 20–29 | 3 | 30.00% |

| 30–39 | 4 | 40.00% | |

| 40–49 | 2 | 20.00% | |

| over 50 | 1 | 10.00% | |

| Subtotal: 10 | 50.00% | ||

| Woman | 20–29 | 2 | 20.00% |

| 30–39 | 3 | 30.00% | |

| 40–49 | 3 | 30.00% | |

| over 50 | 2 | 20.00% | |

| Subtotal: 10 | 50.00% | ||

| Total | 20 | 100.00% |

| Occupation | Number of People | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 5 | 25.00% |

| Nurse | 4 | 20.00% |

| Parents of Children | 2 | 10.00% |

| Hospital Administrator | 2 | 10.00% |

| Designer | 5 | 25.00% |

| Child psychologist | 2 | 10.00% |

| Total | 20 | 100.00% |

| Gender | Age | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man | under 25 | 21 | 26.92% |

| 25–35 | 35 | 44.87% | |

| 35–45 | 13 | 16.66% | |

| over 45 | 9 | 11.53% | |

| Subtotal: 78 | 39% | ||

| Woman | under 25 | 39 | 31.96% |

| 25–35 | 47 | 38.52% | |

| 35–45 | 22 | 18.03% | |

| over 45 | 14 | 11.47% | |

| Subtotal: 122 | 61% | ||

| Total | 200 | 100.00% |

| Questions | Options | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you received pediatric outpatient care within the past 12 months? | Yes | 602 | 75.16 | 75.16 |

| No | 199 | 24.84 | 100 | |

| How many children are there in the family? | 1 | 583 | 72.78 | 72.78 |

| 2 | 144 | 17.98 | 90.76 | |

| 2 or more | 74 | 9.24 | 100 | |

| Transportation to the hospital | Walk | 42 | 5.24 | 5.24 |

| Bike | 46 | 5.74 | 10.99 | |

| Motorcycle/battery car | 85 | 10.61 | 21.6 | |

| Bus/Subway/Light Rail | 140 | 17.48 | 39.08 | |

| Taxi/online car-hailing | 105 | 13.11 | 52.18 | |

| Private car | 383 | 47.82 | 100 | |

| Is the waiting area comfortable? | Very comfortable | 194 | 24.22 | 24.22 |

| More comfortable | 286 | 35.71 | 59.93 | |

| General | 93 | 11.61 | 71.54 | |

| Not very comfortable | 128 | 15.98 | 87.52 | |

| Very uncomfortable | 100 | 12.48 | 100 | |

| The importance of the outpatient facility area | Unimportant | 131 | 16.35 | 16.35 |

| Somewhat important | 262 | 32.71 | 49.06 | |

| Very important | 408 | 50.94 | 100 | |

| How long did you wait before receiving treatment? | Less than 10 min | 139 | 17.35 | 17.35 |

| 10–30 min | 329 | 41.07 | 58.43 | |

| 30–60 min | 243 | 30.34 | 88.76 | |

| 1 h or more | 90 | 11.24 | 100 | |

| Are you receiving timely information about your child’s visit process? | Yes | 528 | 65.92 | 65.92 |

| No | 273 | 34.08 | 100 | |

| Do you support the hospital’s introduction of a digital management system to improve the efficiency of outpatient management? | Support | 527 | 65.79 | 65.79 |

| Do not support | 89 | 11.11 | 76.9 | |

| Uncertain | 185 | 23.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 801 | 100 | 100 | |

| Questions | Options | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your position at the hospital? | Doctor | 28 | 13.93 | 13.93 |

| Nurse | 36 | 17.91 | 31.84 | |

| Radiologic Technologist | 18 | 8.96 | 40.8 | |

| Pharmacist | 28 | 13.93 | 54.73 | |

| Physiotherapist | 20 | 9.95 | 64.68 | |

| Social worker | 53 | 26.37 | 91.04 | |

| Administration staff | 18 | 8.96 | 100 | |

| In your work, have you ever been complained about for medical errors or other reasons? | Wrong or inaccurate diagnosis | 15 | 7.46 | 7.46 |

| The treatment plan is not suitable | 13 | 6.47 | 13.93 | |

| Poor experience, improper use of equipment | 25 | 12.44 | 26.37 | |

| Poor communication with patients | 87 | 43.28 | 69.65 | |

| Fees are opaque or exorbitant | 23 | 11.44 | 81.09 | |

| Long waiting time and disorganized management | 15 | 7.46 | 88.56 | |

| The treatment effect is not good or the cycle is too long | 15 | 7.46 | 96.02 | |

| Other medical accidents | 8 | 3.98 | 100 | |

| Do you think the current workflow needs to be improved? | Needs improvement | 108 | 53.73 | 53.73 |

| Needs a little improvement | 79 | 39.3 | 93.03 | |

| No need to improve | 14 | 6.97 | 100 | |

| Do you think it is necessary to establish a doctor-patient communication platform? | Necessary | 145 | 72.14 | 72.14 |

| Unnecessary | 19 | 9.45 | 81.59 | |

| Do not know | 37 | 18.41 | 100 | |

| Have you ever encountered a situation where you did not understand, distrusted, or refused to accept the treatment advice? | Yes | 110 | 54.73 | 54.73 |

| No | 36 | 17.91 | 72.64 | |

| Do not know | 55 | 27.36 | 100 | |

| Total | 201 | 100 | 100 |

| Name | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Comprehensive Score Coefficient | Weight Factor | Dimension | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue (after Rotation) | 4.374 | 4.348 | 4.276 | 4.064 | 3.91 | ||||

| Percentage of Variance Explained | 10.93% | 10.87% | 10.69% | 10.16% | 9.77% | ||||

| Manual guidance | 0.0434 | 0.1197 | 0.0491 | 0.0696 | 0.0344 | 0.1017 | 2.17% | Waiting dimension | 16.01% |

| Waiting time | 0.0504 | 0.0703 | 0.1203 | 0.04 | 0.1033 | 0.1085 | 2.31% | ||

| Clear instructions for visiting doctors | 0.0257 | 0.0897 | 0.1135 | 0.0592 | 0.096 | 0.1164 | 2.48% | ||

| Timely information communication | 0.0718 | 0.1676 | 0.0957 | 0.0636 | 0.0404 | 0.1134 | 2.41% | ||

| Privacy protection | 0.0643 | 0.1586 | 0.0803 | 0.0546 | 0.0172 | 0.1099 | 2.34% | ||

| Diagnosis and treatment speed | 0.1213 | 0.0588 | 0.0444 | 0.0396 | 0.0747 | 0.1008 | 2.15% | ||

| Various medical expenses | 0.0843 | 0.0579 | 0.0455 | 0.0495 | 0.1001 | 0.101 | 2.15% | ||

| Number of seats | 0.0654 | 0.0561 | 0.0253 | 0.0943 | 0.0883 | 0.1013 | 2.16% | Waiting Facilities | 24.49% |

| Seat comfort | 0.1186 | 0.0562 | 0.025 | 0.0613 | 0.055 | 0.1021 | 2.18% | ||

| Entertainment facilities | 0.0695 | 0.0609 | 0.033 | 0.1251 | 0.0503 | 0.1071 | 2.28% | ||

| Sanitation status | 0.0786 | 0.3041 | 0.0795 | 0.0686 | 0.0804 | 0.1254 | 2.67% | ||

| Ventilation and lighting | 0.0429 | 0.3982 | 0.0467 | 0.0805 | 0.0615 | 0.1153 | 2.46% | ||

| Noise | 0.0305 | 0.4006 | 0.0593 | 0.0719 | 0.0502 | 0.1177 | 2.51% | ||

| Barrier-free facilities | 0.0344 | 0.4068 | 0.0806 | 0.0667 | 0.0644 | 0.1183 | 2.52% | ||

| Whether the system and method of message notification are intelligent | 0.0446 | 0.3939 | 0.0692 | 0.0497 | 0.0814 | 0.1199 | 2.55% | ||

| Consultation service facilities | 0.04 | 0.1829 | 0.1008 | 0.0635 | 0.0508 | 0.1207 | 2.57% | ||

| Guidance system | 0.0729 | 0.1156 | 0.0936 | 0.0467 | 0.0631 | 0.1215 | 2.59% | ||

| Number of registrations available | 0.0493 | 0.1293 | 0.1178 | 0.0645 | 0.0479 | 0.1177 | 2.51% | Outpatient appointment | 20.18% |

| Lack of appointment information or guidelines | 0.0424 | 0.1347 | 0.1176 | 0.0424 | 0.081 | 0.1172 | 2.50% | ||

| Convenience of Appointment | 0.0575 | 0.0773 | 0.1155 | 0.08 | 0.143 | 0.1221 | 2.60% | ||

| Lack of appointment information or guidance | 0.1026 | 0.0268 | 0.0638 | 0.3105 | 0.13 | 0.1209 | 2.57% | ||

| Appointment system or equipment failure | 0.0597 | 0.0714 | 0.0746 | 0.4236 | 0.0984 | 0.1182 | 2.52% | ||

| Attitude of doctors or hospital staff towards appointments | 0.0716 | 0.0845 | 0.0536 | 0.4273 | 0.0978 | 0.1184 | 2.52% | ||

| Appointment sequence or results | 0.1353 | 0.0663 | 0.0751 | 0.3596 | 0.117 | 0.1147 | 2.44% | ||

| Trouble caused by the epidemic | 0.0813 | 0.0723 | 0.0646 | 0.4298 | 0.0993 | 0.1185 | 2.52% | ||

| Children’s exclusive system | 0.1074 | 0.0786 | 0.0926 | 0.1287 | 0.3659 | 0.1329 | 2.83% | Outpatient management system | 21.67% |

| Doctor’s clinic hours settings | 0.112 | 0.0713 | 0.0921 | 0.1324 | 0.3909 | 0.1328 | 2.83% | ||

| Appointment channel settings | 0.0989 | 0.0702 | 0.0993 | 0.1023 | 0.3987 | 0.1292 | 2.75% | ||

| Real-time message alert system settings | 0.1158 | 0.0851 | 0.112 | 0.1377 | 0.4021 | 0.1335 | 2.84% | ||

| Multilingual system settings | 0.1118 | 0.0608 | 0.1262 | 0.1241 | 0.3656 | 0.1324 | 2.82% | ||

| Children’s medical safety system settings | 0.0908 | 0.0738 | 0.3996 | 0.0798 | 0.0954 | 0.1214 | 2.58% | ||

| Field service system settings | 0.0623 | 0.0748 | 0.3746 | 0.0525 | 0.0487 | 0.1132 | 2.41% | ||

| Hospital staff service training system | 0.113 | 0.0765 | 0.3663 | 0.0469 | 0.1362 | 0.1225 | 2.61% | ||

| Access efficiency | 0.088 | 0.0518 | 0.4022 | 0.077 | 0.0854 | 0.1194 | 2.54% | Outpatient Visiting Process | 17.64% |

| Multiple forms and documents are filled out by patients in different processes | 0.0777 | 0.0605 | 0.396 | 0.0758 | 0.1001 | 0.1247 | 2.65% | ||

| Medical treatment process guidance and guidance | 0.4032 | 0.0322 | 0.075 | 0.0881 | 0.0919 | 0.1174 | 2.50% | ||

| Communication between doctors and nurses | 0.3881 | 0.0284 | 0.0594 | 0.0742 | 0.0939 | 0.1128 | 2.40% | ||

| Lack of efficient interoperability in each link of the process | 0.384 | 0.0593 | 0.0957 | 0.0852 | 0.0954 | 0.1184 | 2.52% | ||

| The process setting is not convenient enough | 0.3951 | 0.0513 | 0.0907 | 0.0871 | 0.0846 | 0.1183 | 2.52% | ||

| Process setup is highly repeatable | 0.3933 | 0.043 | 0.0892 | 0.08 | 0.0844 | 0.118 | 2.51% |

| Dimension | Weights | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Waiting | 16.01% | 1.5 |

| Waiting facilities | 24.49% | 2.0 |

| Outpatient appointments | 20.18% | 2.1 |

| Outpatient management system | 21.67% | 1.7 |

| Outpatient visiting process | 17.64% | 2.0 |

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | ||

| Long wait | 0.719 | −0.23 | 0.569 |

| Lack of clear medical instructions, resulting in wasted time | 0.64 | 0.238 | 0.466 |

| Lack of manual guidance, resulting in wasted time | 0.717 | 0.219 | 0.562 |

| Lack of timely information delivery | 0.661 | 0.118 | 0.451 |

| Lack of privacy | 0.779 | −0.035 | 0.608 |

| Diagnosis and treatment of children’s diseases | 0.138 | 0.817 | 0.686 |

| Various medical expenses | −0.001 | 0.857 | 0.735 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 2.597 | 1.482 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 37.094% | 21.175% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 37.094% | 58.269% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 2.505 | 1.574 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 35.779% | 22.490% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 35.779% | 58.269% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.693 | - | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 1216.331 | - | |

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 21 | - | |

| p-value | 0 | - | |

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | A4 | A5 | ||

| Not enough seats in the waiting area | 0.964 | 0.122 | 0.843 | 0.729 |

| Seats in the waiting area are not comfortable enough | 0.955 | 0.049 | 0.844 | 0.739 |

| Lack of recreational facilities in the waiting area | 0.161 | 0.849 | 0.26 | 0.566 |

| Poor hygiene in waiting area | 0.115 | 0.895 | 0.107 | 0.886 |

| Ventilation and lighting need to be improved | 0.108 | 0.826 | 0.064 | 0.881 |

| Excessive noise in the waiting area | 0.135 | 0.818 | 0.041 | 0.924 |

| The environment is not suitable for children to wait for a long time | 0.125 | 0.203 | 0.758 | 0.901 |

| Barrier-free facilities are not in place | 0.301 | 0.785 | 0.732 | 0.708 |

| Notification system is not advanced enough | 0.165 | 0.884 | 0.721 | 0.824 |

| Insufficient consulting services | 0.183 | 0.864 | 0.766 | 0.784 |

| There is no effective medical guidance system | 0.203 | 0.758 | 0.779 | 0.622 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 5.43 | 1.781 | 1.355 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 49.367% | 16.187% | 12.321% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 49.367% | 65.554% | 77.875% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 4.051 | 2.977 | 1.538 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 36.828% | 27.068% | 13.979% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 36.828% | 63.896% | 77.875% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.857 | - | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 7175.166 | - | ||

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 55 | - | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | - | ||

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A6 | A7 | A8 | ||

| Bookable quantity | 0.911 | 0.184 | 0.146 | 0.919 |

| The appointment process is not clear | 0.827 | 0.207 | 0.399 | 0.886 |

| Convenience of appointment | 0.867 | 0.187 | 0.369 | 0.922 |

| Lack of appointment information or guidelines | 0.839 | 0.284 | −0.025 | 0.785 |

| Appointment system or device malfunction | 0.873 | 0.192 | 0.351 | 0.921 |

| Doctors or hospital staff have a poor attitude towards making appointments | 0.194 | 0.881 | 0.185 | 0.848 |

| Unfair appointment sequence or results | 0.246 | 0.916 | 0.059 | 0.902 |

| Trouble caused by the epidemic | 0.184 | 0.191 | 0.804 | 0.839 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 4.911 | 1.605 | 1.505 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 61.393% | 20.067% | 6.309% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 61.393% | 81.460% | 87.769% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 3.2 | 2.638 | 1.183 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 40.006% | 32.975% | 14.788% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 40.006% | 72.980% | 87.769% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.852 | - | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 6349.277 | - | ||

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 28 | - | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | - | ||

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A9 | A10 | ||

| Children’s exclusive system settings | 0.939 | 0.097 | 0.892 |

| Pediatrician Clinic Time Setting | 0.81 | 0.034 | 0.657 |

| Appointment Route and System Settings | 0.894 | 0.125 | 0.816 |

| Timely information prompt system settings | 0.892 | 0.109 | 0.807 |

| Multilingual system settings | 0.937 | 0.103 | 0.888 |

| Medical Safety System Settings | 0.066 | 0.957 | 0.921 |

| On-site service system settings | 0.027 | 0.899 | 0.809 |

| Setting up a training system for hospital staff | 0.106 | 0.898 | 0.817 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 4.247 | 2.359 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 53.092% | 29.486% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 53.092% | 82.578% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 4.026 | 2.58 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 50.331% | 32.247% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 50.331% | 82.578% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.816 | - | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 5880.694 | - | |

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 28 | - | |

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A11 | A12 | A13 | ||

| Access Process Efficiency | 0.937 | 0.129 | 0.115 | 0.999 |

| Patients need to fill in multiple forms, wasting time and energy | 0.937 | 0.178 | 0.115 | 0.924 |

| Patients are not clear about the process of seeing doctors, lacking guidance and guidance | 0.848 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.767 |

| Physician–nurse communication is unclear, leading patients to misinterpret doctor’s advice | 0.929 | 0.129 | 0.16 | 0.906 |

| Lack of efficient communication between access processes, requiring patients to repeatedly provide the same information and materials | 0.145 | 0.955 | 0.141 | 0.938 |

| The access process is not convenient enough, and patients need to spend a lot of time and effort making appointments for treatment | 0.161 | 0.816 | 0.136 | 0.772 |

| The hospital lacks flexible ways of seeing a doctor, such as remote consultations, evening outpatient services, and weekend outpatient services | 0.222 | 0.965 | 0.833 | 0.998 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 4.641 | 1.957 | 1.706 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 66.306% | 13.670% | 10.083% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 66.306% | 79.976% | 90.059% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 4.177 | 1.073 | 1.054 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 59.669% | 15.334% | 15.056% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 59.669% | 75.003% | 90.059% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.912 | - | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 5293.311 | - | ||

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 21 | - | ||

| p-value | 0 | - | ||

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B3 | ||

| Number of seats in the waiting area | 0.775 | 0.225 | 0.095 | 0.721 |

| Seat comfort in the waiting area | 0.718 | 0.252 | 0.193 | 0.777 |

| Entertainment facilities in the waiting area | 0.204 | 0.238 | 0.605 | 0.755 |

| Sanitation in the waiting area | 0.201 | 0.305 | 0.627 | 0.691 |

| Ventilation and lighting | 0.289 | 0.193 | 0.750 | 0.851 |

| Noise in the waiting area | 0.881 | 0.562 | 0.25 | 0.864 |

| Barrier-free facilities for special needs populations | 0.896 | 0.622 | 0.253 | 0.882 |

| The system and method of message notification is intelligent | 0.874 | 0.754 | 0.258 | 0.854 |

| Medical consultation services | 0.310 | 0.155 | 0.836 | 0.891 |

| Visiting guidance system | 0.285 | 0.210 | 0.884 | 0.907 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 5.658 | 1.637 | 1.098 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 56.577% | 16.370% | 8.979% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 56.577% | 72.947% | 81.925% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 3.960 | 2.373 | 1.860 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 39.602% | 23.727% | 18.597% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 39.602% | 63.329% | 81.925% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.887 | - | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 2362.076 | - | ||

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 45 | - | ||

| p-value | 0 | - | ||

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B4 | B5 | ||

| Manual guidance | 0.833 | 0.024 | 0.694 |

| Waiting time | 0.699 | 0.377 | 0.631 |

| Clear medical instructions to avoid wasting time | 0.797 | 0.283 | 0.715 |

| Timely information communication to avoid wasting time | 0.814 | 0.173 | 0.693 |

| Privacy protection | 0.864 | 0.046 | 0.749 |

| Diagnosis and treatment of children’s diseases | 0.17 | 0.881 | 0.805 |

| Various medical expenses | 0.122 | 0.889 | 0.805 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 3.739 | 1.353 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 53.415% | 19.327% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 53.415% | 72.742% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 3.271 | 1.821 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 46.733% | 26.009% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 46.733% | 72.742% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.824 | - | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 992.918 | - | |

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 21 | - | |

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | B7 | B8 | ||

| Bookable quantity | 0.685 | 0.129 | 0.038 | 0.828 |

| Clear appointment process | 0.733 | 0.104 | 0.086 | 0.843 |

| Convenience of Appointment | 0.177 | 0.842 | 0.261 | 0.808 |

| Lack of appointment information or guidance | 0.503 | 0.678 | 0.196 | 0.964 |

| Appointment system or device malfunction | 0.877 | 0.783 | 0.268 | 0.875 |

| Appointment attitude of doctors or hospital staff | 0.887 | 0.201 | 0.825 | 0.89 |

| Appointment sequence or results | 0.89 | 0.128 | 0.741 | 0.81 |

| Difficulties caused by epidemic prevention and control measures | 0.892 | 0.211 | 0.824 | 0.898 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 4.791 | 1.705 | 1.419 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 59.893% | 21.310% | 5.243% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 59.893% | 81.203% | 86.445% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 3.48 | 2.531 | 0.904 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 43.505% | 31.638% | 11.302% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 43.505% | 75.143% | 86.445% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.886 | - | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 2023.304 | - | ||

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 28 | - | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | - | ||

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B9 | B10 | ||

| Children’s exclusive system settings | 0.847 | 0.29 | 0.802 |

| Pediatrician clinic time setting | 0.9 | 0.244 | 0.87 |

| Appointment route and system settings | 0.884 | 0.275 | 0.857 |

| Real time information prompt system settings | 0.908 | 0.282 | 0.904 |

| Multilingual system settings | 0.858 | 0.301 | 0.827 |

| Medical safety system settings | 0.274 | 0.892 | 0.871 |

| On-site service system settings | 0.182 | 0.881 | 0.81 |

| Setting up a training system for hospital staff | 0.337 | 0.848 | 0.833 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 5.426 | 1.348 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 67.821% | 16.853% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 67.821% | 84.674% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 4.092 | 2.682 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 51.153% | 33.522% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 51.153% | 84.674% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.901 | - | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 2348.467 | - | |

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 28 | - | |

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |

| Name | Factor Loading Coefficient | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B11 | B12 | ||

| Access process efficiency | 0.217 | 0.934 | 0.919 |

| Patients fill out multiple forms and materials | 0.209 | 0.936 | 0.92 |

| Access process guidance and guidance | 0.908 | 0.219 | 0.873 |

| Communication between doctors and nurses | 0.871 | 0.193 | 0.797 |

| Lack of efficient interoperability between access processes | 0.862 | 0.274 | 0.818 |

| The access process settings are not convenient enough | 0.893 | 0.226 | 0.849 |

| High repeatability of access process settings | 0.88 | 0.268 | 0.846 |

| Eigenvalue (before rotation) | 4.752 | 1.269 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 67.885% | 18.134% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (before rotation) | 67.885% | 86.019% | - |

| Eigenvalue (after rotation) | 3.99 | 2.031 | - |

| Percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 57.005% | 29.014% | - |

| Cumulative percentage of variance explained (after rotation) | 57.005% | 86.019% | - |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.866 | - | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 1944.137 | - | |

| Degrees of freedom (DF) | 21 | - | |

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |

| Interviewee | Average Score | Process Improvement Suggestions | Suggestions for Improving Service | Convenience Issues | AI System Improvement Suggestions | Support for Artificial Intelligence Systems | Recommendations for Graded Diagnosis and Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 5.4 | Increase outpatient science promotion | Optimize the update speed of medical devices | Insufficient medical equipment | Improve the electronic medical record system | Support | Strengthen cooperation with community hospitals to achieve hierarchical diagnosis and treatment |

| Specialist nurse | 5.25 | Increase patient education outreach | Strengthen service attitude and communication | Unreasonable appointment times | Complete medical equipment | Support | Realize hierarchical diagnosis and treatment, and promote the family doctor system |

| Outpatient guardian | 4.5 | Reduce waiting times | Increase children’s entertainment facilities | Not enough pediatric specialists | Perfect reservation and registration system | Support | Establish hierarchical diagnosis and treatment management departments to achieve overall resource utilization |

| Administrative staff | 6.5 | Strengthen hospital management processes | Increase medical staff training | Short service life of medical devices | Improve medical device procurement management | Support | Realize hierarchical diagnosis and treatment and strengthen cooperation with primary medical institutions |

| Child psychologist | 5 | Increase children’s counseling services | Strengthen doctor–patient communication and exchange | Improper use of medical devices | Improve medical device use training | Support | Introduce more advanced medical equipment to improve medical efficiency |

| Before Seeing a Doctor | Peer-to-Peer Scheme |

|---|---|

| Orientation of the treatment process | Formulate triage process guidelines, classify, and allocate different types of patients, and divert patients. Provide official website or app to publicize information. |