Advancing Primary Education through Active Teaching Methods and ICT for Increasing Knowledge

Abstract

1. Introduction

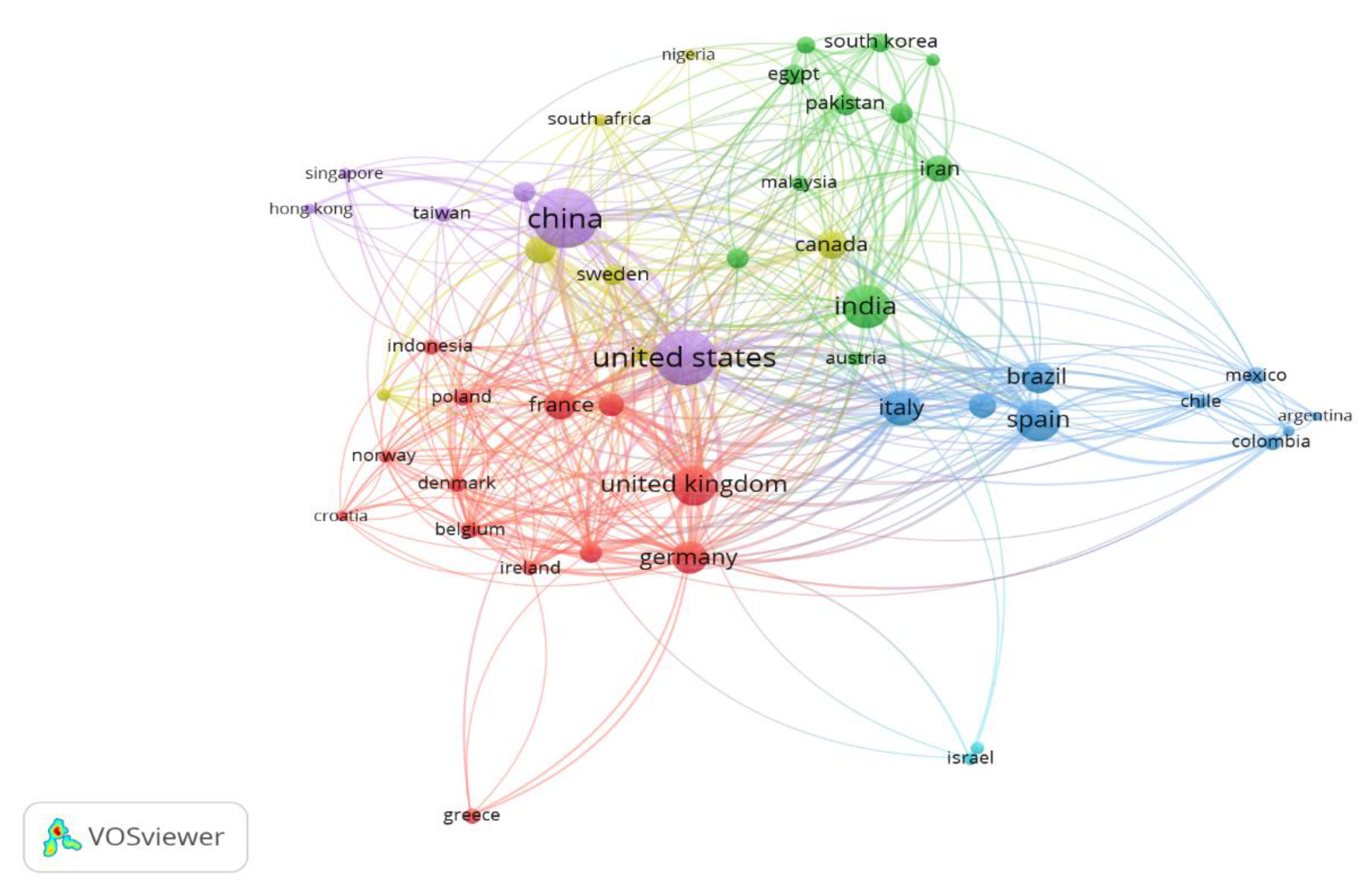

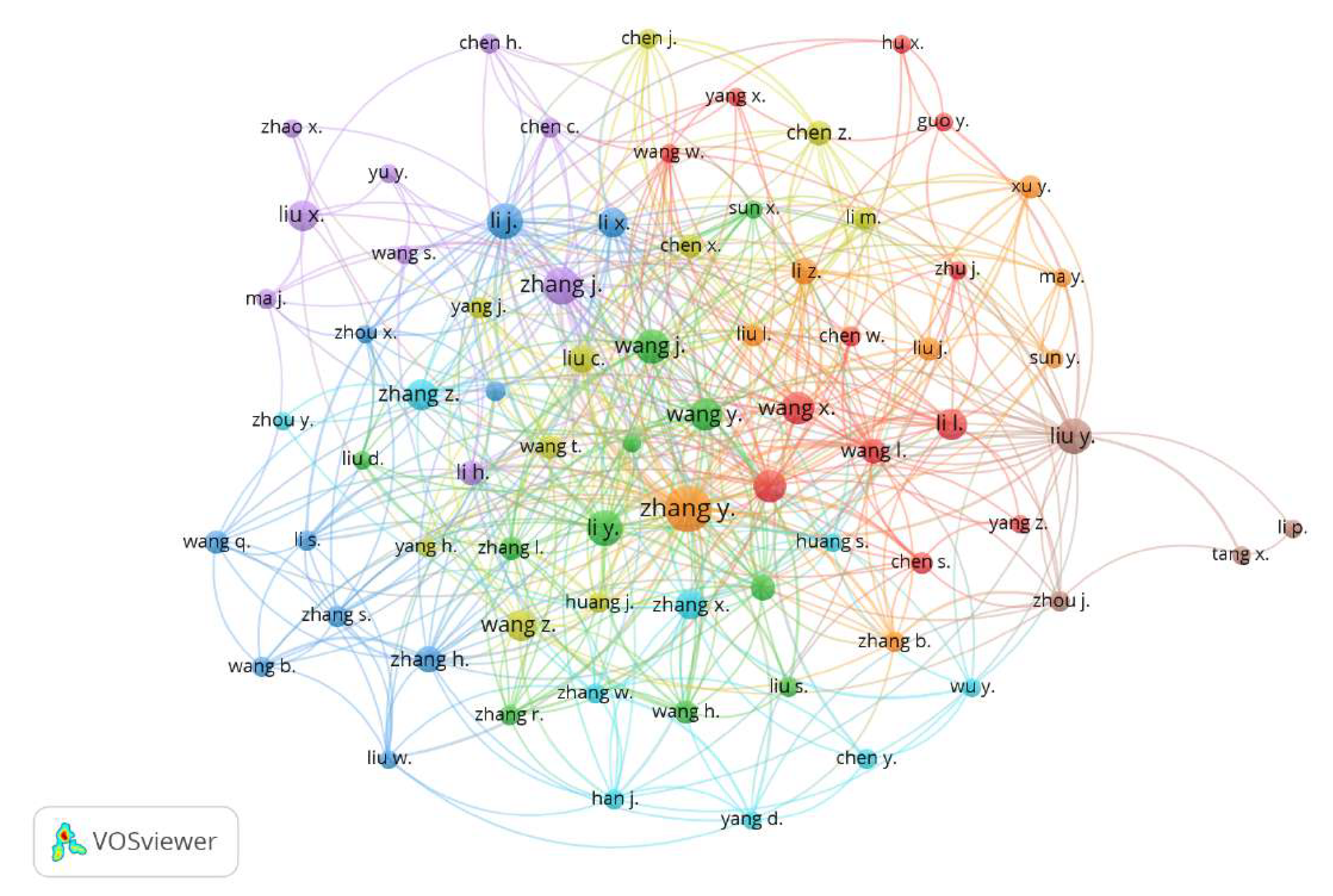

2. Related Works

3. Problem Formulation and Methodology

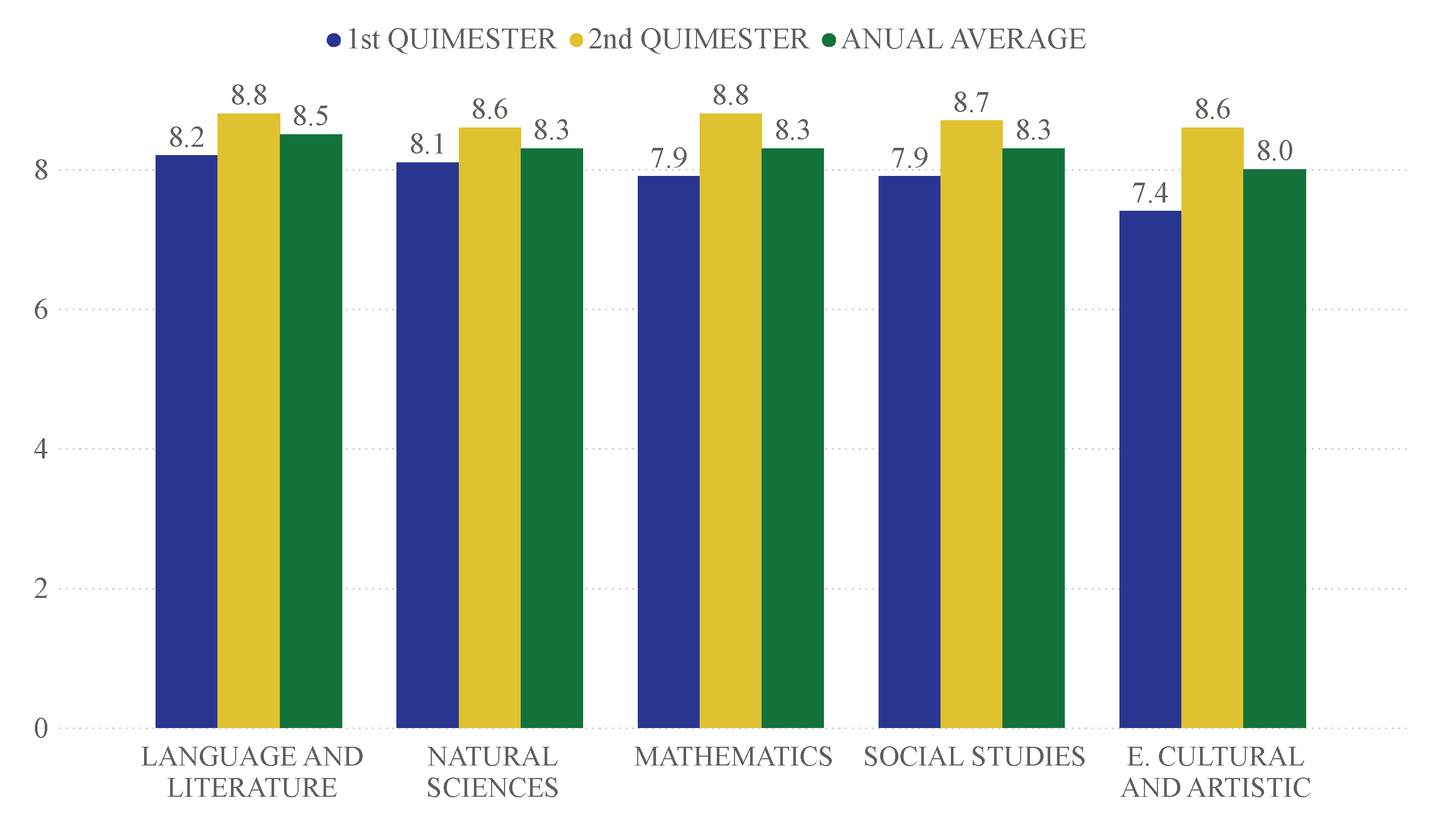

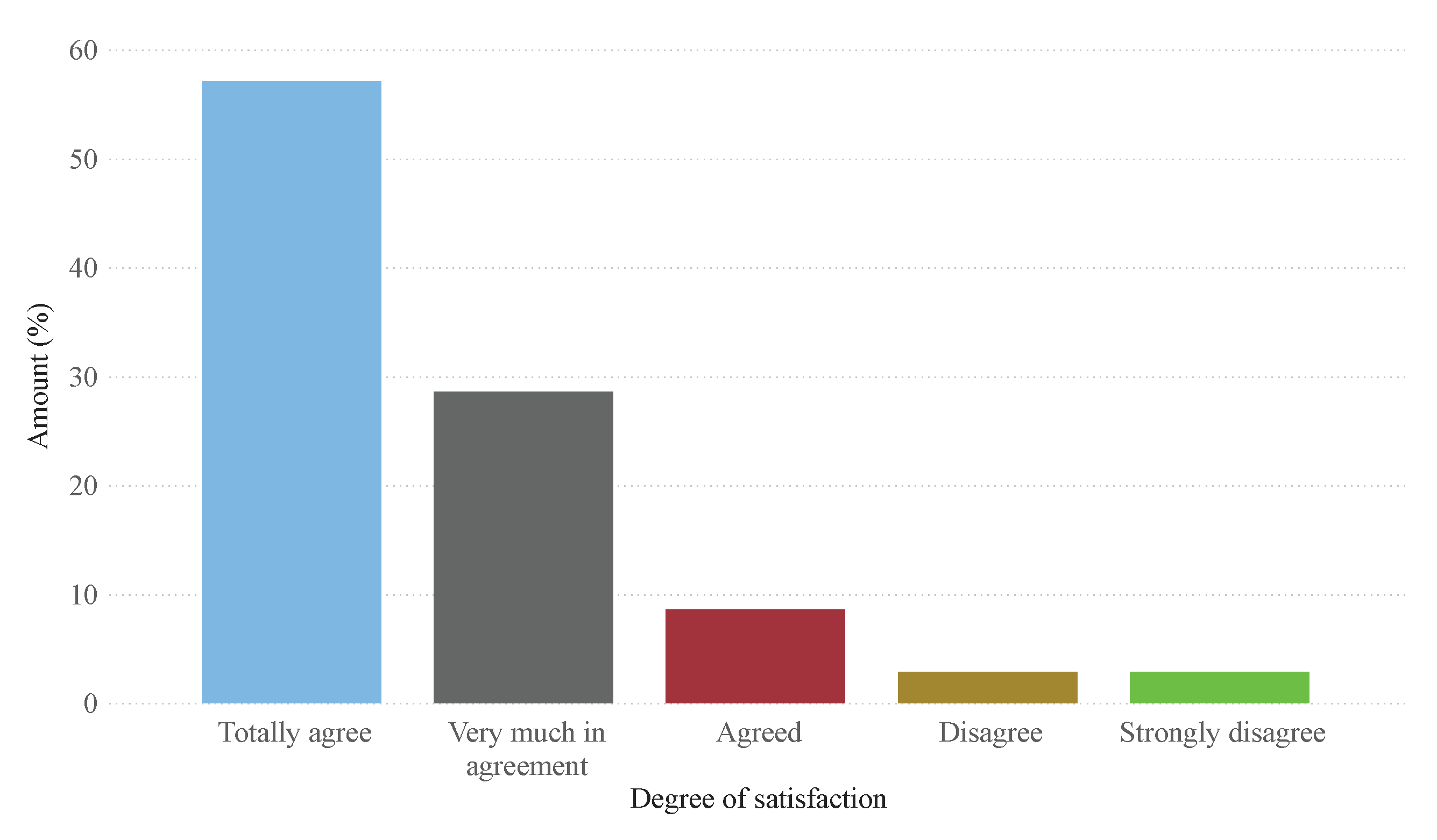

4. Analysis of Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez Huamán, E.L.; Félix Benites, D.E.; Quispe Morales, R.A. Innovación educativa y práctica pedagógica docente en pandemia. Rev. Estud. Interdiscip. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 24, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Espinoza, J.J. Metodologías activas, la clave para el cambio de la escuela y su aplicación en épocas de pandemia. Innova Res. J. 2020, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenaño Barreno, P.N.; González Villavicencio, J.L. Metodologías activas aplicadas en la educación en línea. Rev. CientÍFica Dominio Las Cienc. 2021, 7, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkowski, Z.; Jadeja, R.; Dutta, N. Peer learning in technical education and it?s worthiness: Some facts based on implementation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 172, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.C. Student Satisfaction with Audio-Visual Flipped Classroom Learning: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, A.; Inga, E. Information and Communication Technologies for Education Considering the Flipped Learning Model. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardoun, H.; González, C.; Collazos, C.A.; Yousef, M. Exploratory study in iberoamerica on the teaching-learning process and assessment proposal in the pandemic times. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2020, 21, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, J.; Inga, E. Methodological experience in the teaching-learning of the English language for students with visual impairment. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Zambrano, M.G.; De la Peña Consuegra, G.; Linzán Saltos, M.F. Tecnologías educativas emergentes para fortalecer el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en los estudiantes de tercero Bachillerato en tiempos de pandemia. MQRInvestigar 2023, 7, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivieso Guerrero, T.S.; Erazo Bustamante, S.E. Políticas educativas y Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (TIC): Una mirada al Ecuador. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valores 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangari, M.; Inga, E. Educational innovation in the evaluation processes within the flipped and blended learning models. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche Carreño, S.F. Fornulación e implementación de un modelo de innovación educativa para fortalecer las capacidades en estudiantes de educación media, en la resolución de problemas con el uso de TICS Y STEM. Politécnico Grancolombiano 2019, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inga, E.; Inga, J.; Cárdenas, J. Planning and Strategic Management of Higher Education Considering the Vision of Latin America. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta Jaramillo, C.A.; Puentestar Gómez, M.A.; Valenzuela Chicaiza, C.V.; Vega Muñoz, E.A.; Sandoval Flores, J.E. Implicaciones de la educación presencial y virtual en el contexto ecuatoriano. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. 2023, 7, 4051–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, J.; Inga, E. Interactive Peer Instruction Method Applied to Classroom Environments considering an Educational Engineering Approach to Innovate the Teaching-Learning Process. Educ. Sci. 2022, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, Z.; Alhendawi, M.; Bashitialshaaer, R. Un estudio exploratorio de los obstáculos para lograr la calidad en la educación a distancia durante la Pandemia de COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Sierra, Á.A.; Ortega Iglesias, J.M.; Cabero-Almenara, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Development of the teacher’s technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) from the Lesson Study: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, F.; Revelles Benavente, B. La perspectiva post-cualitativa en la investigación educativa: Genealogía, movimientos, posibilidades y tensiones. Educ. Siglo XXI 2019, 37, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandia Saldivia, B.E.; Luzardo Briceño, M.; Aguilar-Jiménez, A.S. Apropiación de las Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación como Generadoras de Innovaciones Educativas. Cienc. Docencia Tecnol. 2019, 30, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Cobeña, E.I.; Briones Ponce, M.E.; Moreira Sánchez, J.L.; Zambrano Dueñas, G.L.; Menéndez Solórzano, F.A. Metodología educativa basada en recursos didácticos digitales para desarrollar el aprendizaje significativo. MQRInvestigar 2023, 7, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A. Educational Innovation in Adult Learning Considering Digital Transformation for Social Inclusion. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanyà Rebollo, J.; De Oliveira, J.M. Los elementos didácticos del aprendizaje móvil: Condiciones en que el uso de la tecnología puede apoyar los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Edutec. Rev. Electrón. Tecnol. Educ. 2022, 80, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzola, B.; Ecos, A.; Ibarra, M.J.; Vilca, E.; Aquino, M.; Caceres, M.C. Collaborative methodology and ICTs for Math Learning in undergraduate students. In Proceedings of the EDUNINE 2019—3rd IEEE World Engineering Education Conference: Modern Educational Paradigms for Computer and Engineering Career, Lima, Peru, 17–20 March 2019; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Villa, S.; García-Guliany, J.; Hernández-Palma, H.; Steffens-Sanabria, E. Competencias docentes y transformaciones en la educación en la era digital. Form. Univ. 2019, 12, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, R. Using design-based research to explore the influence of context in promoting pedagogical reform. EDeR. Educ. Des. Res. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, P.; Zambrano, H.; Vallejo Pilligua, P.Y.; Bravo Cedeño, G.M. Estructuras mentales en la construcción de aprendizaje significativo. Cienciamatria 2019, 5, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingavelez-Guerra, P.; Robles-Bykbaev, V.E.; Perez-Munoz, A.; Hilera-Gonzalez, J.; Oton-Tortosa, S.; Campo-Montalvo, E. RALO: Accessible Learning Objects Assessment Ecosystem Based on Metadata Analysis, Inter-Rater Agreement, and Borda Voting Schemes. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 8223–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Ren, L. Genetic evolution analysis of 2019 novel coronavirus and coronavirus from other species. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoor, F.; Botha, A.; Herselman, M. Conceptualizing mobile digital literacy skills for educators. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Mobile Learning 2020, Paris, France, 28–29 October 2020; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingavelez-Guerra, P.; Robles-Bykbaev, V.E.; Perez-Munoz, A.; Hilera-Gonzalez, J.; Oton-Tortosa, S. Automatic Adaptation of Open Educational Resources: An Approach From a Multilevel Methodology Based on Students’ Preferences, Educational Special Needs, Artificial Intelligence and Accessibility Metadata. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9703–9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanca-Arohuanca, J.; Supo-Condori, F.; Sucari Leon, R.; Supo Quispe, L. El problema social de la educación virtual universitaria en tiempos de pandemia, Perú. Innovaciones Educ. 2020, 22, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo Ríos, S.L.; Tigre Ortega, F.G.; Tubón Nuñez, E.E.; Sánchez Villegas, D.S. Objetos Virtuales de Aprendizaje como estrategia didáctica de enseñanza aprendizaje en la educación superior tecnológica. Recimundo 2019, 3, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-González, M.E.; Belmonte, J.L.; Segura-Robles, A.; Cabrera, A.F. Active and emerging methodologies for ubiquitous education: Potentials of flipped learning and gamification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrín Miranda, J.J. Aplicación de metodologías activas en modalidad e-learning en el año 2022: Caso carrera de comunicación. Rev. Cient. Uisrael 2023, 10, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquerre Ramos, L.A.; Pérez Azahuanche, M.Á. Retos del desempeño docente en el siglo XXI: Una visión del caso peruano. Rev. Educ. 2021, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital’, D.; Dupláková, D.; Duplák, J.; Mital’ová, Z.; Radchenko, S. Implementation of Industry 4.0 Using E-learning and M-learning Approaches in Technically-Oriented Education. TEM J. 2021, 10, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño Garrido, C.; Garay Ruiz, U.; Themistokleous, S. De la revolución del software a la del hardware en educación superior. Ried. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2018, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Rodríguez, A.; Martín González, Y.; Hernández Martín, A. Evaluación de la competencia digital del alumnado de Educación Primaria. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2023, 41, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Pino, U.; Anaya Diaz, S.L.; Lara Silva, E.A.; Carrascal Reyes, M.C. Las Innovaciones Educativas con TIC como generadoras de cambio en las prácticas pedagógicas de aula. Ing. Innov. 2019, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanuza Gámez, F.I.; Rizo Rodríguez, M.; Saavedra Torres, L.E. Uso y aplicación de las TIC en el proceso de enseñanza- aprendizaje. Rev. Cient. FAREM-Estelí 2018, 25, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasó Rius, J.; Arderiu Antonell, M. Herramientas tecnológicas para el seguimiento del alumnado en la FP. Prácticum 2019, 4, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Gaviria, D.A.; Jiménez Guevara, J.E. Constructivismo y tecnologías en educación. Entre la innovación y el aprender a aprender. Rev. Hist. Educ. Latinoam. 2021, 23, 61–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Work | Problem | Constraint | Proposal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Active Methodologies | Student Participation | Educational Processes | Virtual education | Virtual platforms | Technological Knowledge | Pedagogical Knowledge | Motivation | Interactive Learning |

| Rocha, 2020 [2] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Buenaño, 2021 [3] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| MendozaZambrano, 2023 [9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lassoued, 2020 [16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Rubio, 2021 [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Saldivia, 2019 [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Hernandez, 2019 [18] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Martinez, 2022 [1] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Braso, 2019 [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Valdivieso, 2020 [10] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Proposal Authors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Survey | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you have internet at home? | 2 | 4 | 5 | 24 |

| 2. Is your home internet used by several family members? | 1 | 3 | 6 | 25 |

| 3. Have you used a computer and its peripherals such as monitor, keyboard, mouse, and CPU? | 4 | 6 | 5 | 20 |

| 4. Do you use cell phones, tablets, or laptops at home or school to review material related to your school activities? | 4 | 7 | 8 | 16 |

| 5. Do you know what ICT is, and do you apply it in your school work? | 8 | 9 | 12 | 6 |

| 6. Do you consider ICT to be important in your academic training? | 4 | 3 | 9 | 19 |

| 7. Are ICTs challenging to understand and use? | 8 | 10 | 12 | 5 |

| 8. Can ICT replace traditional educational resources such as notebooks and the chalkboard? | 5 | 9 | 13 | 8 |

| 9. Are ICTs only for leisure and free time? | 9 | 11 | 9 | 6 |

| 10. Are ICTs useful tools to develop school work and activities? | 3 | 3 | 15 | 14 |

| 11. Are ICTs a means of fostering interpersonal relationships among students? | 4 | 9 | 13 | 9 |

| 12. Are ICTs support to complement your knowledge? | 2 | 5 | 14 | 14 |

| 13. Would you like the challenge of being able to use ICT? | 2 | 4 | 12 | 17 |

| 14. Would you like to apply the knowledge acquired through ICT? | 1 | 5 | 7 | 22 |

| 15. Would you like to exchange opinions about school activities in chat rooms or forums with classmates and teachers? | 3 | 4 | 11 | 17 |

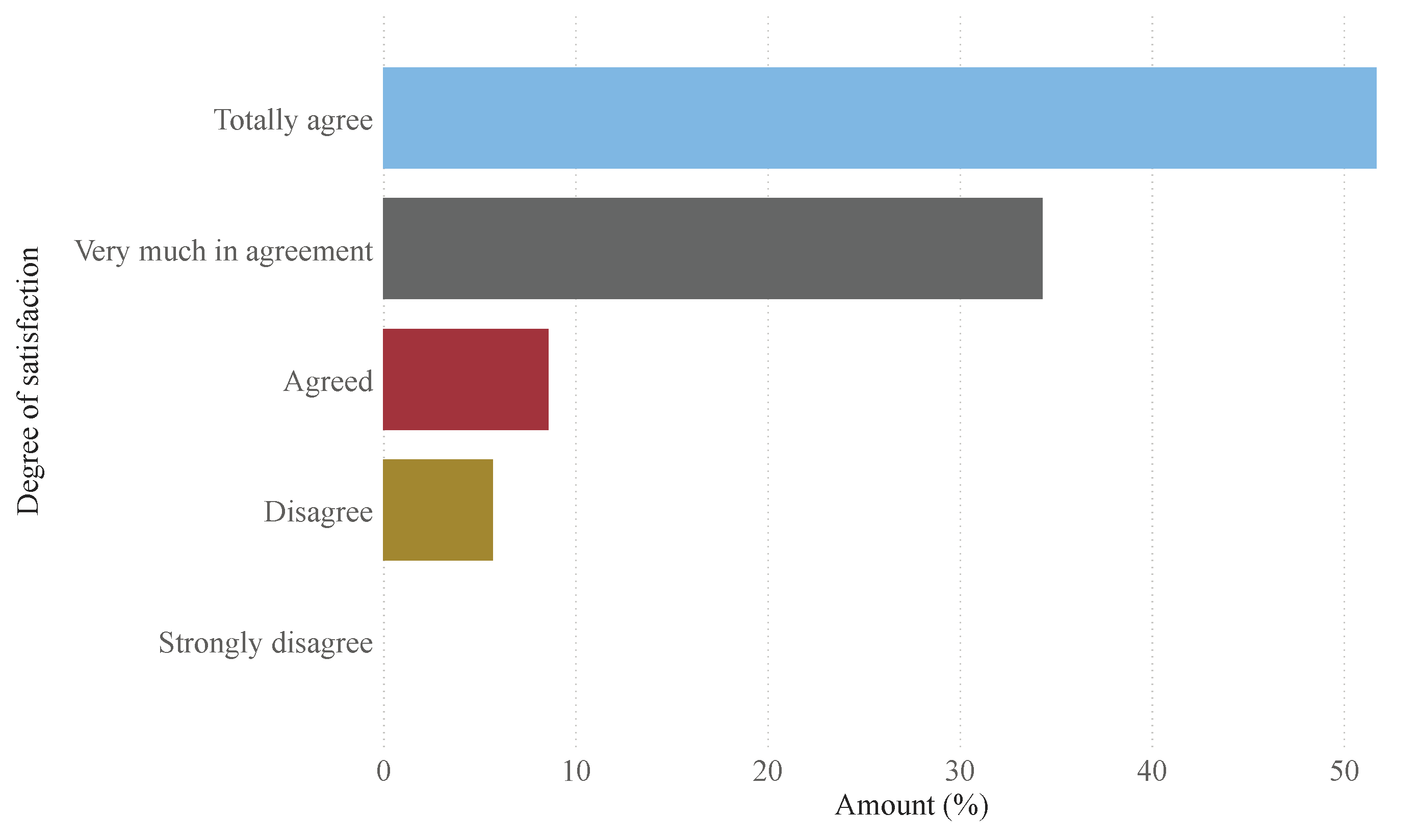

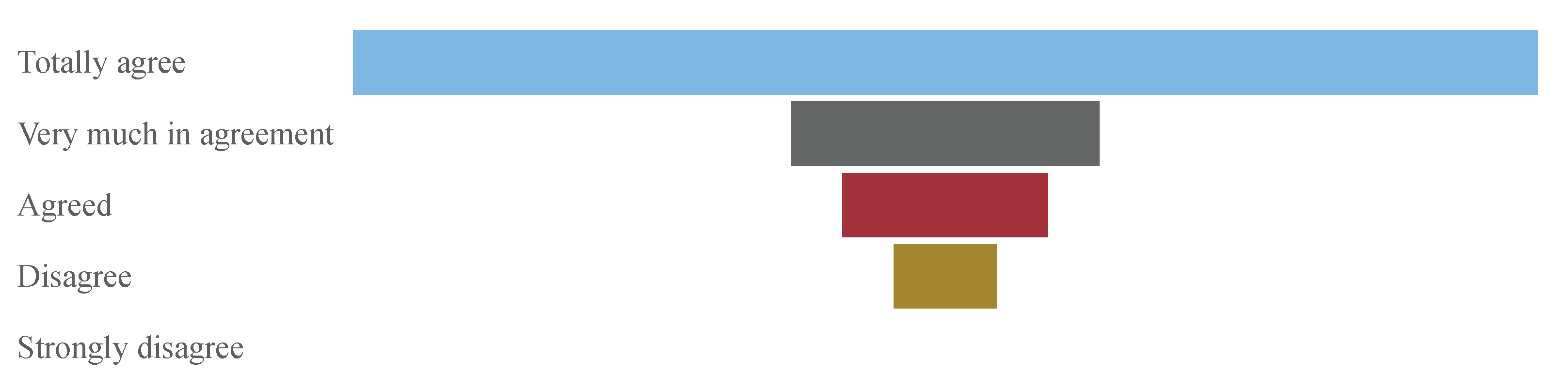

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Strongly Disagree Survey | Disagree | Agree | Very Much in Agreement | Totally Agree |

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Q1 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5.7% | 94.3% |

| Q2 | 37.1% | 8.6% | 11.4% | 22.9% | 20% |

| Q3 | 2.9% | 2.9% | 8.6% | 28.6% | 57.1% |

| Q4 | 2.9% | 2.9% | 14.3% | 22.9% | 57.1% |

| Q5 | 0% | 5.7% | 8.6% | 34.3% | 51.4% |

| Q6 | 0% | 5.7% | 11.4% | 37.1% | 45.7% |

| Q7 | 0% | 5.7% | 5.7% | 31.4% | 57.1% |

| Q8 | 0% | 2.9% | 11.4% | 22.9% | 62.9% |

| Q9 | 0% | 2.9% | 11.4% | 20% | 65.7% |

| Q10 | 0% | 2.9% | 14.3% | 31.4% | 51.4% |

| Q11 | 0% | 5.7% | 17.1% | 22.9% | 54.3% |

| Q12 | 0% | 0% | 8.6% | 28.6% | 62.9% |

| Q13 | 0% | 2.9% | 8.6% | 34.3% | 54.3% |

| Q14 | 0% | 2.9% | 5.7% | 14.3% | 77.1% |

| Q15 | 0% | 5.7% | 11.4% | 17.1% | 65.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garzon, P.; Inga, E. Advancing Primary Education through Active Teaching Methods and ICT for Increasing Knowledge. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129551

Garzon P, Inga E. Advancing Primary Education through Active Teaching Methods and ICT for Increasing Knowledge. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129551

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarzon, Paul, and Esteban Inga. 2023. "Advancing Primary Education through Active Teaching Methods and ICT for Increasing Knowledge" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129551

APA StyleGarzon, P., & Inga, E. (2023). Advancing Primary Education through Active Teaching Methods and ICT for Increasing Knowledge. Sustainability, 15(12), 9551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129551