Abstract

Eastern Africa is a relatively dry area, with a considerable pastoralist population, which is among the poorest segments of society. Pastoralism is a form of subsistence lifestyle, and while pastoralists produce a large proportion of the region’s livestock products, they are not covered well by statistical recording. Pastoralists are experts in keeping livestock in arid rangelands, but they often suffer from land alienation, environmental degradation, and conflict with other land use intentions. The semiarid rangelands in Eastern Africa are home to spectacular savanna wildlife populations, attracting substantial conservation and tourism revenues. Estimations indicate that pastoralism generates significant economic values in the national income due to livestock production and maintenance of tourism attractions. To assess this contribution, the concept of total economic valuation (TEV) is applied. The main aim of the paper is to analyze the contribution of pastoralism to the tourism-related GDP of Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, where considerable numbers of pastoralists live. Because of the lack of statistical data on pastoralism, the second objective is to construct a database of indicators that measure the extent of pastoralism for these countries for 2004, 2014, and 2018. The methodology includes the construction of the above database using secondary sources, and then to apply correlation and regression analysis on this database and the economic and tourism performance data series of the studied four countries. The results of the analysis showed that the extent of pastoralism is positively related to GDP and to value added by tourism and agriculture, and international tourism receipts are positively related to pastoralism’s contribution to GDP. The tourism competitiveness index (TTCI) was found to be negatively related to the size of the pastoralism sector. The policy implications of our findings are that pastoralist societies are increasingly important not only for their marketed economic output, but for their services provided to tourism and to the environment; therefore, instead of neglecting them, they should be more in the focus of development.

Keywords:

pastoralism; Eastern Africa; Ethiopia; Kenya; Uganda; Tanzania; total economic valuation; tourism contribution 1. Introduction

Eastern Africa, or the Greater Horn of Africa, covers 11 countries: Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. It is a relatively dry area, although it includes wet mountain regions and is situated by the Equator. Altogether, 47% of Eastern Africa (328 million hectares) is dryland, making up 5.3% of the world’s drylands; 37% of the region belongs to the semiarid zone, and 30% to the arid and hyperarid zones [1]. Regarding land use, 26% of land in Africa is classified as forests (783 million hectares), and 27% is grassland, i.e., shrublands and savannahs (817 million hectares), while 12% of the area is cropland (350 million hectares) in 2020. Compared with 2000, the cropland area increased by 19 million hectares (0.6%), while the forest area decreased by 15 million hectares (0.5%) and the grasslands by 4 million hectares (0.2%) [2]. These countries are among the poorest quarter of the world, and their economies greatly rely on the agricultural sector, with outstanding high (approximately 70%) [3,4] and 28% undernourished [5].

1.1. Pastoralism: Definition and Descriptive Data for East Africa

Pastoralist households are among the poorest of the population. The traditional livestock production and the nomadic lifestyle is a form of subsistence lifestyle, and although pastoralists produce a large proportion of the region’s livestock products sold at the domestic and foreign markets, the high share of production consumed by the pastoralist communities escapes statistical recording. According to a widely used definition, pastoralist production systems are farming systems that are characterized by at least 50% of the gross household incomes coming from pastoralism or from activities related to it, or else, by more than 15% of the households’ food energy consumption involving their milk or dairy production [6]. In a more recent and comprehensive definition, pastoralism is an economic activity and a cultural identity. As an economic activity, it is an animal production system that utilizes the typical instability of rangeland environments, where key resources, such as nutrients and water for livestock, become available in short-lived and largely unpredictable concentrations [7,8]. This system has three distinct components interacting with each other: (i) the natural resources (pasture, water, minerals); (ii) the herd (livestock), and (iii) the family and other wider social institutions, including labor and governance [9]. Pastoralists derive most of their income or sustenance from keeping domestic livestock, using most of the feed from natural sources rather than cultivated or closely managed ones [10]. Livestock herds are social, cultural, and spiritual assets, as well as economic assets, providing food and income for the family [9,11]. Pastoralist livelihoods are changing, and besides livestock raising, revenues for wildlife conservation and tourism are emerging as alternative income sources, although their share is rather low yet [12]. Rangelands are currently being lost due to land degradation, conservation projects, to crop production, urban land, and other factors [13]. Since 2000, the rangelands of Eastern Africa have experienced huge changes in human populations and shifting land use (Table 1) [14].

Table 1.

Pastoralists and pastoralist areas, selected countries (2004–2018).

To give an accurate description of the pastoral systems in Africa, data availability should be far better than it is today, in spite of the recent improvements of the data collection methodology about mobile pastoralist populations [11].

Pastoralism can be classified as nomadic and transhumant. Nomadic pastoralism is a way of living with no fixed seasonal location, whereas transhumant pastoralism is a mobile system where the pastoralists rotate the same areas across different seasons [21,22]. Although nomadic herding is often stereotyped as an outdated, inefficient way of livestock production, the comparative productivity of open-range pastoralist production over commercial ranching is quite high, under comparable ecological conditions. Considering the productivity of ranching as 100%, the productivity of pastoralist production is 157% in Ethiopia (by MJoule per hectare per year of gross energy edible by humans), 185% in Kenya, 188% in Botswana, 100–800% in Mali (by kg protein per hectare), and 150% in Zimbabwe (in dollar value per hectare) [11]. This is due to the livestock management practices applied by the nomads, which make them more ready to handle risks and shocks involved in animal production. The major factor in this is mobility: when drought or disease strikes, mobile households can move away to avoid being affected, while sedentary ranching systems have to handle these issues at their own cost. The continuous movement of the herds also makes the quality of the meat better. The herders also possess traditional indigenous knowledge about the agroclimatic zones, soils, vegetation, and seasonal grazing areas, which also contribute to the better quality, less risk, and lower production costs.

As the main aim of livestock management in a pastoralist system is to maintain communal grazing areas, pastoralists are responsible for maintaining the ecosystem so as to obtain enough grass to feed their livestock. Thus, pastoralism has a mechanism of conserving the rangeland biodiversity and protecting the ecosystem. Therefore, pastoralism is a nature-friendly sustainable production system adapted to dryland conditions [22]. Traditional practices—including mobility, grazing reserves, and the use of fire—based on indigenous knowledge lead to positive environmental outcomes: enhanced biological diversity and ecosystem integrity and resilience [12]. As long as there is sufficient grazeland that allows optimal stocking density, the mobile herding practices are beneficial to the environment. Pastoralists use a holistic approach, combining soil, vegetation and livestock, and offer tools for biomass and soil carbon restoration, contributing to the mitigation of climate change, maintaining a balance of vegetation, wildlife and, land use. Grazing animals can enhance plant populations by spreading seeds, while diverse plant life supports diverse insects, reptiles, and birds across landscapes. Grazing also reduces the buildup of dry grass, lowering the risk of intense fires [22]. Besides, climate regulation services, tourism, gum, and resins and honey production are also of significant value, though this list of goods and ecosystem services attributed to pastoralism is certainly not complete [23].

1.2. Tourism and Rural Communities in East Africa

Tourism is one of the most important industries in the world, and tourism in Africa shows faster growth than in most parts of the world, contributing 8.5% of the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018 [24,25]. Tourism supported 24.3 million jobs in Africa, and the continent received around 5% of the estimated 1.4 billion international tourist arrivals in 2018. Africa is only beginning to realize its full potential in tourism, accounting only for 1% of the USD 1.7 trillion global tourism revenue [26], and only 5% of all international tourist arrivals in 2018 [27]. The recent years showed the vulnerability of tourism to events restricting mobility, such as the COVID pandemic in 2020–2021, and terrorist attacks, leading to a decrease in tourism spending and contraction of the economy in the short term and long term [28,29]. Although the countries in the African continent have experienced exponential growth in tourism since the 1970s, this growth in arrivals has not been reflected in economic, social, or environmental benefits for host communities [25].

East Africa is one of the major tourism destinations in Africa, and natural resources are among its most important tourism appeals [14,30]. However, local communities rarely benefit much from living in the most attractive nature-based destinations, although host communities play a crucial role in the sustainable management of these areas [25,31,32,33]. As wildlife has been an important attraction to tourists in the continent, local rural communities may consider the option of contributing to nature-based or wildlife tourism through their agricultural activities [33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

In rangelands, competition between wildlife and livestock can pose ecological and economic challenges. Wildlife may offer opportunities for supplementary—or even main—income generation and may provide an alternative to livestock production, but it may bring about increasing competition for resources (water, pasture, and migration routes), and the decline in wildlife habitats leads to increased wildlife–livestock–human conflicts due to damage caused by livestock, humans, and wildlife to each other [13,40,41,42].

In Eastern Africa, wildlife watching is one of the main attractions for international tourists, and provides the majority of their national income from tourism. The economic effects of tourism also stimulate other sectors of the economy, and through this multiplying effect, even relatively low levels of tourism can lead to considerable revenues and to local economic development [43]. However, as human and livestock population grows, the sustainable development and management of vital wildlife resources and of the safari tourism sector remains a major concern [44,45].

The tourism resources of the region are related to pastoralism in many ways. The main attraction, i.e., its rich and unique wildlife, shares its living area with pastoralist communities. The colorful ways of local lifestyles, cultural festivals, handicrafts, and food, also attractions for tourists, are again often provided by pastoralist communities, although they may not benefit much from tourism [44,46,47]. The majority of the revenues are collected by tour operators and rarely reach local communities.

1.3. The Research Objectives

The main aim of the paper is to analyze the contribution of pastoralism to the tourism-related GDP of East Africa—more precisely, of Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, where considerable numbers of pastoralists live.

The second objective is to build up a database of indicators measuring the extent of pastoralism for several countries and years. There are no thorough statistical databases about pastoralism—the relevant countries do not collect data about the pastoralist population, or if they do, data are scarce and irregular. Most research publications that provide information about pastoralist communities rely on estimated data, various studies often contradict each other, and values presented are for sporadic years, and for only a few countries or regions. The total economic valuation method of assessing the economic significance of pastoralism follows a more or less standard methodology, but the provided data are only for a few years, and these years are usually not the same for various countries. Therefore, our aim was to create a database that allows us to compare several years and several countries in East Africa, covering a reasonably long time span. Due to available resources, 3 years, 2004, 2014, and 2018, were chosen with four countries: Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

A research gap exists: quantification of the relationship between the extent of pastoralist activities and the overall economic performance of specific countries, in general, and the relationship of pastoralism and tourism performance in particular. The contribution of the present paper to the state of the art is to set up a consistent—though small—database spanning 14 years and covering four countries. Then the paper assesses the contribution of pastoralism to the tourism performance of the sample countries.

The structure of the rest of the paper is the following: Section 2 describes the methodology, data sources, and procedure of data collection. Section 3 presents the statistical analysis of the data. Section 4 discusses the research findings, and Section 5 closes the paper with conclusions and policy implications.

2. Methodology and Data

2.1. Methodology to Assess the Economic Contribution of Pastoralism to the Economy and to Tourism

Pastoralism supports economic activity in a number of nontraditional industries through the supply of inputs. The most important two sectors affected are agriculture and tourism, although these benefits are not captured by official government statistics [48]. Future tourism development in Africa is likely to be a mix of safari and cultural tourism, to which the pastoralist input will be harder to omit or neglect [49].

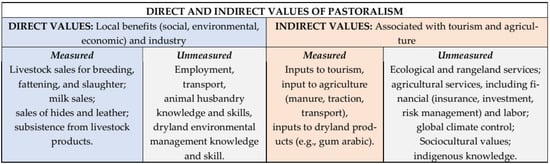

To assess the contribution of pastoralism to the economy, the concept of total economic valuation (TEV) is applied. TEV was originally developed in cost–benefit analysis to deal with ‘priceless’ assets that would otherwise be neglected by standard procedures of appraisal. The study of pastoralist TEV began in the early 2000s and has continued mostly by pastoralism-related organizations, such as the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), IUCN World Initiative for Sustainable Pastoralism, and Intergovernmental Authority on Development in Eastern Africa (IGAD). The TEV methodology captures the value of both the marketed and nonmarketed goods and services produced by pastoralism as a complex livelihood system, not only as livestock production [49]. The concept of TEV assumes that the pastoralist system is also a natural resource management system that provides a wide range of services and products, such as biodiversity, tourism attractions, and raw materials, although some of these either cannot be measured or, when measured, are often underestimated [50]. They can be either direct or indirect values (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework for the total economic valuation (TEV) of pastoralism. Source: authors’ compilation based on [48,51,52].

- Direct values consist of

- Measurable products and outputs (livestock sales, meat, milk, hair, and hides);

- Less easily measured values (employment, transport, knowledge, and skills).

- Indirect values include

- Tangibles, such as inputs into agriculture (manure, traction, transport, breeding stock, etc.), and complementary products, such as gum arabic, honey, medicinal plants, wildlife, and tourism;

- Intangible values, including financial services (investment, insurance, credit, and risk management), ecosystem services (biodiversity, nutrient cycling, and energy flow), and a range of social and cultural values.

This broad framework is applied for assessing the value of pastoralism, although pastoralist resource and livestock production datasets are scanty and often based only on estimations [45,51].

2.2. Methodology of Data Collection and Database Compilation

The dataset was collected from international statistical databases, compiled from literature sources, and computed based on the collected source data in the following way:

- Country-level tourism and agriculture data

- The World Travel and Tourism Reports [53] give the values of international tourism receipts and the total economic contribution of tourism to GDP, derived from the tourism satellite accounts. This analysis shows that, e.g., in Ethiopia, the total contribution of tourism was approximately 1.5–1.7 times higher than the value of international tourism receipts in 2004, 2014, and 2018. In Kenya, this ratio is 2.5–4.7; in Uganda, it varies between 1.3 and 3.3; and in Tanzania, 2.1 and 4.1 [53,54].

- The contribution of agriculture to the national GDP is computed from the FAO database [55], and the share of livestock production in agricultural value added is also computed from the same source.

- Value added by pastoralism

Data on the total measurable value added by pastoralism is more complicated to collect. Considering the available resources, research papers were used, which analyzed the economic contribution of pastoralism in various countries and various years, to set up a small but consistent database for four countries and the years 2004, 2014, and 2018 (as these were the years having the most reliable research results to rely on).

For Ethiopia, the database was set up in the following way:

- For 2004, data for Ethiopia are found in [45], stating that the total contribution of pastoralism to GDP was 16.6%, and pastoralism’s contribution to tourism provided 50% of tourism value added. This gave the foundation to compute the agriculture-related value of pastoralism, simply deducting the tourism-related pastoralist value from the total GDP provided by pastoralism.

- For 2014, the data from [56] gave the total USD value of pastoralism. Then the tourism-related pastoralist output was measured as 50% of the total tourism value, and the rest of the values were computed the same way as for 2004. These results are similar to estimations based on the process described in [57], taking the rate of protected areas within the country territory and using the same rate to estimate tourism-related pastoralist values.

- For 2018 in Ethiopia, the same methodology was followed as for 2004, based on data from [23].

- For the rest of the countries, pastoralism values related to agriculture:

- For 2004, 2014, and 2018, the agriculture-related pastoralist output values are estimated based on [48] for Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (for Ethiopia, the same method resulted in very similar values as those computed above). This analysis states that, in the four analyzed countries, approximately 75–95% of the total livestock output is produced by pastoralists. Then the FAO database [55] is used for estimating the total livestock output, and from it, the actual value of pastoralist agricultural output can be estimated (assuming that pastoralists’ agricultural output is mainly livestock related). Similar, though slightly different values can be drawn from [51].

For Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, the tourism-related pastoralism values:

- For 2014 Kenya, Ref. [57] gave the total proportion of pastoralism value to total GDP, from which the total USD value was computed. Then from the data in [58] and [59], the proportion of tourism-related and agriculture-related pastoralist GDP values were computed.

- For 2018 Kenya, Ref. [59] gives the total pastoralism output and states that agricultural outputs are 90.5% of this value, and tourism-related values are 9.5%. This gives the USD values of tourism-related and agriculture-related pastoralist values, respectively.

- For 2014 and 2018 Uganda, the total value of pastoralism in Uganda is given in [19] for 2018. The proportion of the total value of pastoralism to GDP for 2014 is given in [58], from which its dollar value is computed. In [19], the tourism-related value from pastoralism is also given both for 2014 and for 2018. The difference between the total pastoralism value and the tourism-related pastoralism value gives the rest, i.e., the agriculture-related value.

- For Tanzania in 2014 and 2018, tourism-related pastoralist values are computed in the same way as described in [51,60], taking the rate of protected areas within the country territory and using the same rate to estimate tourism-related pastoralist values.

Table 2 summarizes a list of variables used for further analysis. The variables are grouped by their contents: Group A contains general economic indicators, Group B refers to the indicators of tourism performance, and Group C refers to variables measuring the economic data related to pastoralism.

Table 2.

Variable list.

- Data analysis tools

Besides descriptive statistics, first, a simple correlation analysis was carried out to reveal relationships between pastoralism indicators and tourism-related measures. The correlation of pastoralism performance indicators (variables of Group C in Table 2) was computed to see how various measures are related, whether data are consistent, and to facilitate a better understanding of the pastoralism processes of the 14-year-long period. Then pastoralism indicators (Group C) were correlated with tourism performance indicators (Group B) and to general economic variables (Group A) to evaluate the economic significance of pastoralism in the national economy in general and in tourism outcomes in particular. Finally, correlations between tourism performance (Group B) and general economic indicators (Group A) were computed as a way of control, to see if the relationships of tourism and pastoralism are not simply the extrapolation of pastoralism’s general economic significance, but are more specific relationships. Before the analysis, the normality of the data series (and their ln-transformed versions) was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistics, and only the total area, the total population, and the ln-transformed pastoral area were found to violate the normality assumption.

The second tool was multiple regression analysis, the independent variables being those that measure the extent of pastoralism and the dependent variables being those that measure the economic performance of tourism. Due to the limited size of our database, the regression models were kept simple, with only a few independent variables in each relationship, to avoid overfitting. Finally, the per capita value produced by pastoralism was compared with the per capita GDP to assess the economic efficiency of pastoralist societies.

3. Results

The analysis focused on four countries of East Africa, namely, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. These are the four largest countries in Eastern Africa; altogether they make up more than 61% of the total population of Eastern Africa, [15] and, altogether, 70–78% of all international tourist arrivals to Eastern Africa in 2018–2019 [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. Figure 2 presents the research area, and Table 3 illustrates the importance of agriculture and of tourism in the economies of these four countries.

Figure 2.

The geographic location of Eastern Africa with the studied four countries. Source: Authors’ own construction based on [63] (p. 4).

Table 3.

The share of agriculture and tourism in national GDP, 2004, 2014, and 2018.

3.1. Database Construction

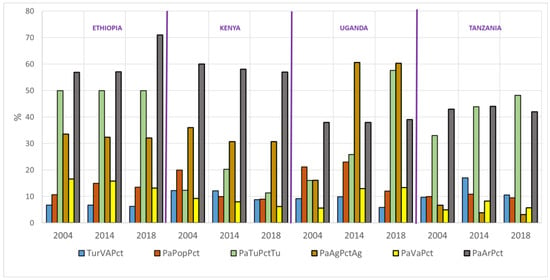

As a result of the data collection procedure described in the methodology section, a database was established (Table 4). As the table shows, the indicators of the three countries differ considerably. However, the pastoralism sector contributes to the national GDP, to the total tourism economy, and to the traditional agricultural sector in each of these countries. The total contribution of pastoralism to national GDP ranges from a modest 4.93% (Tanzania, 2004) to 16.6% (Ethiopia, 2004). Although Kenya and Ethiopia show a decreasing trend, Uganda actually reflects an increasing pattern, while Tanzania ’s values fluctuate in the 14-year-long period (see PaVaPct in Table 4). It is worth noticing that, in the less developed Ethiopia and Uganda, the contribution of pastoralism to both agriculture and tourism is rather high (above 15%, as s shown by the variables PaAgPctAg and PaTuPctTu), indicating the problems of omitting pastoralism from the official statistics. It is also worth mentioning that, in most years and countries, the share of pastoralism in the national GDP (PaVaPct) is higher than the proportion of pastoralists in the total population (PaPopPct). This means that, although pastoralism is often stereotyped as an inefficient, obsolete form of production, it may actually be more productive than the nonpastoralist part of society. Some of the mentioned features are visualized in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Tourism and pastoralism indicators for Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, 2004–2018.

3.2. Correlation Outputs

Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 reflect the correlation coefficients between the variables of our database, indicating significant correlation relationships.

Table 5.

Correlations of pastoralism indicators.

Table 6.

Correlations between tourism resources, tourism performance, and pastoralism.

Table 7.

Correlations within tourism performance and general indicators.

As Table 5 shows, pastoral land area is positively correlated with pastoralism’s contribution to agriculture, to GDP, and it is also positively correlated with the proportion of pastoral land within the total area of the country. The share of agricultural value added by pastoralism within the total agricultural value of the country is also positively correlated with the share of total value added by pastoralism within the national income. This relationship is also reflected in the positive correlation between agricultural value added by pastoralism and total value added produced by pastoralism. Pastoralist population shares are not correlated with any of the other pastoralism indicators, but the absolute number of pastoralists is positively correlated with pastoralist area, with the absolute value added by pastoralists, with the share of pastoralism in GDP, and with its share in agricultural value added.

In Table 6, a feature worth noticing is the strong positive correlation between national GDP and the money value of pastoralism, as well as the money value of agricultural and tourism value added by pastoralism. International arrivals are not correlated in any way with pastoralism, but international tourism receipts are positively related to pastoralism’s value added to tourism, to agriculture, and to GDP. These show that a larger pastoralist sector goes together with larger tourism revenues in absolute money value.

Finally, tourism performance indicators and their relation to the general national economy show no surprises. The total GDP is positively related to international tourism arrivals and receipts and to total tourism contribution to GDP—i.e., the size of the tourism sector is positively related to GDP. International arrivals also positively correlate with total tourism contribution to GDP—but not with international tourism receipts. This shows that more visitors do not necessarily spend more directly, but through their demand for services, they still generate higher indirect and induced incomes (Table 7).

3.3. Regression Analysis

Although correlation analysis showed that several pastoralism-related indicators have strong positive correlations with tourism performance indicators, regression analysis is the proper tool for revealing the influence of pastoralism on tourism. Regression results are presented in Table 8. As we have a small sample of only 12 cases for each variable, regression models were established with only a few independent variables to avoid overfitting. Another concern was to avoid multicollinearity between the independent variables (see the VIF values in Table 8, all being well below 5). Dependent variables were those that measure tourism performance (arrivals, receipts, tourism value added), while independent variables were chosen to reflect the extent of pastoralist activities (pastoralist area, pastoralist population density, and value added by pastoralism). The dependent variables were used in their ln-transformed forms, as the visual analysis showed the nonlinear character of the possible relationships.

Table 8.

Regression relationships between pastoralism and tourism performance.

As a result of experimenting with various model structures, the absolute indicators of tourism—i.e., arrivals, receipts, and the total value added by tourism in GDP—were found to be dependent on the absolute size of the pastoralist area (negatively), the pastoralist value added to GDP (positively), and pastoralist population density (only for arrivals, negatively). The tourism-related pastoralist value added, as % of the total tourism contribution to GDP, was found to depend on the logarithmic values of the proportion of the pastoralist land area (with a negative impact), the proportion of the pastoralist population (negative impact), the pastoralist population density (positive impact), and the percentage share of the pastoralist value added within GDP (positive impact). The per capita GDP was also included as a control variable, but it did not show any significant impact (Table 8). The R2 values were high, for each of the models was between 0.734 and 0.901—the smallest value for arrivals and the largest one for tourism value added—indicating the strong explanatory power of the respective models.

The derived models indicate that the larger the pastoralist value added, the higher the total tourism receipts and the total tourism income of the country; i.e., the economic performance of pastoralism has a positive impact on the size of the tourism industry. The negative impact of the size of the pastoralist area diminishes this positive impact, but as the beta values (standardized coefficients) of Table 8 show, this negative impact is smaller than the positive impact of the first variable. As it was shown earlier, there is a medium-level positive correlation between pastoralist value added (PaVa) and pastoralist area (PaAr)—though this does not generate multicorrelation in the model—and this shows that the positive impact of the pastoral value added is stronger, when this is produced in a smaller area, in a more concentrated way.

In the case of total international arrivals as dependent variable, all the three independent variables showed significant impact, but only the pastoralist value added is of positive effect, while both the pastoralist area and the pastoralist population density have negative impacts on arrivals. This means that while the larger pastoralist outputs lead to more international arrivals, the larger areas and the larger numbers of pastoralists diminish this positive impact—i.e., arrivals are enhanced most when the pastoralist output is produced on a smaller area and less population per unit area, leaving more space to nature reserves, protected areas, and other land use forms.

The last regression relationship has the tourism-related pastoralist value added, as % of the total tourism contribution to GDP, as dependent variable. This variable measures the extent to which the tourism-related pastoralist activities can contribute to the total value added by tourism within GDP. The higher this proportion, the more important the contribution of pastoralism to tourism. As the regression parameters show, the larger total pastoralist value added and the larger pastoralist population density significantly increase the sector’s share in the tourism-related value added, i.e., its importance within national tourism-related GDP. This positive impact is diminished by the larger share of pastoralism in the area and population of the countries analyzed, though as the beta values indicate, the positive impacts are stronger than the negative ones. This again shows that the contribution of pastoralism to tourism is highest when pastoralism is a high-performance sector, but its shares in population, and in area, are moderate—i.e., pastoralism activities are more concentrated. The national income level did not have any significant impact on this relationship.

Finally, the economic efficiency of pastoralist societies was compared with the national averages. Pastoralist per capita value added was measured by pastoralist value added divided by pastoralist population, while the national value was computed by GDP divided by total population. The mean pastoralist value added per capita was found to be 0.6082 thousand USD (with a standard deviation of 0.3923), while the mean GDP per capita was 0.8071 thousand USD (with a standard deviation of 0.4911). The two series do not differ significantly: mean difference was 0.1193, t-statistics = 3.361, df = 11, significance level p = 0.0064, 95% confidence interval for mean difference was 0.0688 to 0.3298. This shows that pastoralist societies are not less efficient economically than the national average.

4. Discussion

As correlation analysis showed, countries with larger pastoralist areas have higher absolute numbers of pastoralists and larger pastoralist value added in GDP. Comparing per capita value added in the pastoralism sector with per capita GDP values, the difference is not significant; i.e., pastoralism is not less efficient economically than the national average. This is similar to the findings of [11] for Ethiopia, Botswana, Kenya, Mali, and Zimbabwe. Therefore, the presence of a significant pastoralist sector as an economic activity and a way of life does not necessarily hinder the overall economic development of the Eastern African countries.

Looking at the specific industries linked to pastoralism, the value added by the main activity, agriculture (nomadic livestock herding) is also positively related to GDP, and this was also established by [23,45,48,51,56] for various years and countries. This means that the higher agricultural value produced by pastoralists, the higher the national GDP—i.e., pastoralism does not divert the resources from more productive sectors. Our findings also show that the agricultural value added by pastoralism is also positively related to the number of pastoralists and to the total pastoral land area, indicating the resource-extensive character of nomadic herding.

The other sector that may benefit from pastoralism is tourism: pastoralism can provide cultural attractions to tourists by the traditions, customs, food, and typical lifestyle, and it also provides important ecosystem services, which are important for nature-based tourism. This is similar to findings in [31,32,33,34,35,36] for specific countries. Our research shows that a larger pastoralist value added to tourism, to agriculture, and to GDP correlate with higher international tourism receipts, though not with international tourist arrivals. While the absolute sizes of pastoralist lands and of the pastoralist population both positively correlate with total and agricultural value added by pastoralism, these are not correlated with pastoralism’s value added to tourism. For tourism, a rather competitive industry, the natural and cultural appeals are key factors in generating higher incomes.

Pastoralism, as a traditional lifestyle, can contribute to the cultural heritage and cultural appeal of the countries, while nature reserves and protected natural sites are associated with land areas that are often closed from agricultural activity, including nomadic grazing. Although pastoralism may provide important ecosystem services to maintaining natural landscapes, the most important nature-based tourism attraction sites are closed from pastoralism. Similar findings were established in [37,38,39] for Kenyan Maasai pastoralists.

Our first objective was to assess the role of pastoralism in the tourism performance of the researched countries. The findings of the regression analysis showed that the total value produced by pastoralism enhances the value of tourism receipts, tourism value added, and tourism arrivals, though the positive impact is most felt when it is achieved in a smaller area, in a more concentrated way. This can be explained by the fact that the agricultural products of pastoralism and its cultural and ecosystem services are all attractive factors for tourists and, therefore, by attracting more tourists, lead to higher spending and higher value added.

It was also found that a higher pastoralist population density and a higher share of pastoralist outputs in GDP contribute to higher shares of pastoralism within the tourism output. This indicates that an expanding pastoralist sector brings about an increasing contribution of the sector to tourism; i.e., the development of pastoralism will take place not only in agriculture but in services provided for tourism-related activities. Former studies [70,71,72] support the importance of tourism infra- and superstructure over natural and cultural appeals in tourism competitiveness. However, these factors are of rather low quality in pastoralist areas and communities, compared with settled rural communities and urban regions. The factors that make a less developed African country appealing to the global tourism market are nature-based tourism, the often exotic wildlife, which flourishes in wild, nomadic environments, while the usual convenience elements of the developed tourism industry are simply not available. This may be one explanation why Africa is still unable to fully utilize its tourism potential [73].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The relationship between tourism and national income generation is quite complex and cannot be simply equated to visitor spending. It is dependent on many factors, including transport infrastructure, which is often underdeveloped in East Africa [74]. In rural regions, tourism is strongly connected to the ecological and natural resources and their sustainable management by rural communities [75,76]. The benefits of tourism are not evenly distributed; less favored groups of society may not receive their fair share from it [77,78,79,80].

As we could establish, pastoralism has a significant role in income generation, which is reflected by its share in the national GDP, and in the tourism-related income of the countries. This is true for all the four analyzed countries and in each assessed year. This is similar to several former studies [19,23,45,48,56,57,59], and our findings show that pastoralism can contribute to tourism at a similar extent as to the traditional, agriculture-based sectors. Even in Ethiopia and Uganda, where the tourism sector is less developed, the contribution of pastoralism to tourism is very similar to that of agriculture. Pastoralism may play a more significant role in the national GDP than its population size would suggest, as its share in GDP, and especially in agricultural and tourism value added, is higher than in population. Considering that agriculture and tourism are two crucial exporter sectors in these countries, a shrinking pastoralist society would result in a declining pastoralist economy, which could lead to crucial losses not only in domestic incomes, but in export revenues too. This underlines the suggestion of several studies; i.e., pastoralism is actually a rather efficient form of utilizing unfavorable environmental conditions [11,64].

As our results state, a larger pastoralist sector is actually beneficial to the sectors of tourism and agriculture and, through these sectors, to the national economy. The efficiency of pastoralism was found to be not less than the average efficiency of the economy, measured by value added per capita. This is an important fact, considering that pastoralism utilizes unfavorable natural resources, which would not be suitable for sedentary agriculture. However, pastoralism has to compete with other land use forms, especially with protected areas and heritage sites, i.e., areas restricted and closed before pastoralist grazing. This has also been established in various country studies and shows that with the spreading of the Western-style conservation ideas, which separate local people from the conservation areas, pastoralists tend to be pushed out of their former habitats. However, as our analysis shows, this may not be economically viable, as the size of pastoralist rangelands positively relates the total value added by pastoralism, which, in turn, positively relates to GDP. On the other hand, former research indicates that pastoralists are efficient conservationists, using the environmentally unfavorable drylands in a way that they can use the same areas from year to year, maintaining their conditions in a sustainable way [22,36,40].

As our results show, pastoralism is positively related to the incomes generated by tourism. The value added by pastoralism to the national economy can lead to increased tourism revenues, and it can also significantly contribute to higher international arrivals. International tourist arrivals may often be motivated by promotion about landscape, wildlife, and local unique culture, i.e., images associated with pastoralist lifestyles, these being the major tourism attractions in the region. Pastoralism provides a vital input to tourism, as it maintains the rangelands by grazing and herding. Thus, pastoralists conserve the environment and help to maintain the habitats of wildlife [51]. International tour operators also advertise these trips using images of pastoralists, while pastoralists’ cultural performances and handicrafts have clearly helped spark interest in the region [69,70]. Unlike agriculture, pastoralism is one of the few land uses able to coexist with wildlife, as domesticated and wild animals exploit different ecological niches. For these reasons, it is crucial to have a clearer picture of the role pastoralism plays in African economies.

A pastoralism-related database of several countries and several years can give a basis for analyzing the economic significance for larger time spans and more extensive areas than it has been done in former studies that focused on individual years and countries. Our findings could establish these results for 3 particular years spanning a 14-year time period and for four different countries applying the same methodology of quantitative analysis.

The limitations of our research are related to the difficulties of data collection, and the small database we built up does not allow more sophisticated statistical analyses. To overcome this, a more systematic data collection would be needed about pastoralist regions in Africa for more years and more countries. Currently, most of the countries involved in pastoralism in Africa do not collect precise data about pastoralist communities, so setting up databases for analysis has to rely on estimations, which cannot be absolutely precise. The need for this systematic data collection is emphasized by the increasing amount of evidence published about pastoralists being excellent conservationists, guarding the sustainable utilization of their dryland areas [48,49,50]. Considering the forthcoming climate change and dangers of environmental degradation, this issue is of increasing importance, underlining the positive image and significance of pastoralism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.B., M.B.G., L.D.D. and Z.H.; methodology, Z.B. and Z.H.; software, Z.B.; validation, Z.B., M.B.G., L.D.D. and Z.H.; formal analysis, Z.B. and Z.H.; investigation, Z.B.; resources, Z.B., M.B.G. and Z.H.; data curation, Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.B., M.B.G., L.D.D. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.B., M.B.G. and Z.H.; visualization, Z.B.; supervision, L.D.D.; project administration, L.D.D.; funding acquisition, L.D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the Stipendium Hungaricum, Tempus Public Foundation, for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haile, M.; Livingstone, J.; Shibeshi, A.; Pasiecznik, N. (Eds.) Dryland Restoration and Dry Forest Management in Ethiopia: Sharing Knowledge to Meet Local Needs and National Commitments. A Review; PENHA; Ethiopia Ethiopia and Tropenbos International: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; African Union. Africa Open Data Environment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/health-nutrition-and-population-statistics# (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- World Bank. Data from database: World Development Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- FAO; ECA; AUC. Africa—Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2021: Statistics and Trends; FAO: Accra, Ghana, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, J. Les Grands Themes du Development Pastoral et le cas de Quelques Pays Africains; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. Policy for the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands; Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeye, B.A. Unsustain the sustainable: An evaluation of the legal and policy interventions for pastoral development in Ethiopia. Res. Policy Pract. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremeskel, E.N.; Desta, S.; Kassa, G.K. Pastoral Development in Ethiopia: Trends and the Way Forward. In Development Knowledge and Learning; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Waiswa, C.D.; Mugonola, B.; Kalyango, R.S.; Opolot, S.J.; Tebanyang, E.; Lomuria, V. Pastoralism in Uganda. Theory, Practice, and Policy; International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, C. (Ed.) Prospects for Livestock-Based Livelihoods in Africa’s Drylands. World Bank Studies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homewood, K.M.; Chenevix Trench, P.; Brockington, D. Pastoralist livelihoods and wildlife revenues in East Africa: A case for coexistence? Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2012, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liniger, H.P.; Mekdaschi Studer, R. Sustainable Rangeland Management in Sub-Saharan Africa—Guidelines to Good Practice; TerrAfrica—World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Bern, Switzerland; World Bank Group (WBG): Washington, DC, USA; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, J.; Sabates-Wheeler, R.; Caravani, M.; Biong Deng Kuol, L.; Manzolillo Nightingale, D. Newly evolving pastoral and post-pastoral rangelands of Eastern Africa. Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT-QA Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Rodgers, C. Equipped to Adapt? A Review of Climate Hazards and Pastoralists’ Responses in the IGAD Region; IOM & ICPALD: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Markakis, J. Pastoralism on the Margin; Minority Rights Group International: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam. Survival of the fittest—Pastoralism and climate change in East Africa. In Oxfam Briefing Paper 116; Oxfam International: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development. Total Economic Valuation of Pastoralism in Uganda—Study Report; IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development (ICPALD): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- PINGO’s Forum. Socio-Economic Contributions of Pastoralism as Livelihood System in Tanzania: Case of Selected Pastoral Districts in Arusha, Manyara and Dar es Salaam Regions; Pastoralists Indigenous Non-Governmental Organization’s Forum (PINGO): Arusha, Tanzania, 2016; Available online: www.pingosforum.or.tz (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Blench, R. You Can’t Go Home Again: Pastoralism In The New Millennium; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Abduletif, A.A. Benefits and challenges of pastoralism system in Ethiopia. Stud. Mundi—Econ. 2019, 6, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development. Total Economic Valuation of Pastoralism in Ethiopia—Study Report; IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development (ICPALD): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Signé, L.; Johnson, C. Africa’s Tourism Potential Trends, Drivers, Opportunities, and Strategies. Africa Growth Initiative; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Africas-tourism-potential_LandrySigne1.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Juma, L.O.; Khademi-Vidra, A. Community-Based Tourism and Sustainable Development of Rural Regions in Kenya, Perceptions of the Citizenry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimeria, C. Africa’s Tourism Industry Is Now the Second Fastest Growing in the World. 2019. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/1717902/africas-tourism-industry-is-second-fastest-growing-in-world (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Chisadza, C.; Clance, M.; Gupta, R.; Wanke, P. Uncertainty and tourism in Africa. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoya, E.T.; Efthymiou, M.; Nikitas, A.; O’Connell, J.F. The Effects of Diminished Tourism Arrivals and Expenditures Caused by Terrorism and Political Unrest on the Kenyan Economy. Economies 2022, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliku, O.; Kyiire, B.; Mahama, A.; Kubio, C. Tourism amid COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts and implications for building resilience in the eco-tourism sector in Ghana’s Savannah region. Heliyon 2021, 7, 07892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okello, M.M.; Novelli, M. Tourism in the East African Community (EAC): Challenges, opportunities, and ways forward. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 14, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekalign, M.; Groot Zevert, N.; Weldegebriel, A.; Poesen, J.; Nyssen, J.; Van Rompaey, A.; Norgrove, L.; Muys, B.; Vranken, L. Do Tourists’ Preferences Match the Host Community’s Initiatives? A Study of Sustainable Tourism in One of Africa’s Oldest Conservation Areas. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopino, S.; Piazzi, C.; Opio, J.; Muhwezi, D.K.; Ferrari, E.; Caporale, F.; Sitzia, T. Tourist Agroforestry Landscape from the Perception of Local Communities: A Case Study of Rwenzori, Uganda. Land 2022, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melubo, K.; Lovelock, B. Living Inside a UNESCO World Heritage Site: The Perspective of the Maasai Community in Tanzania. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, G.; Meintjes, D.; Kelso, C.; Fitchett, J. Tourism as an incentive for rewilding: The conversion from cattle to game farms in Limpopo province, South Africa. J. Ecotourism 2019, 18, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyara, V.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Tourism expansion and economic growth in Tanzania: A causality analysis. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Snyman, S.; Rylance, A. Revenue sharing from tourism in terrestrial African protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 27, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoga, J.; Olago, D.; Ouma, G. Cultural heritage as a pathway for sustaining natural resources in the Maasai’s Pastoral Social-Ecological System in Kajiado County, Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 17, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieti, D.; Nthiga, R.; Plimo, J.; Sambajee, P.; Ndiuini, A.; Kiage, E.; Mutinda, P.; Baum, T. An African dilemma: Pastoralists, conservationists and tourists—reconciling conflicting issues in Kenya. Dev. South. Afr. 2020, 37, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osano, P.M.; Said, M.Y.; de Leeuw, J.; Ndiwa, N.; Kaelo, D.; Schomers, S.; Birne, R.; Ogutu, J.O. Why keep lions instead of livestock? Assessing wildlife tourism-based payment for ecosystem services involving herders in the Maasai Mara, Kenya. Nat. Resour. Forum 2013, 37, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Livestock, Climate and the Politics of Resources: A primer; Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holechek, J.; Valdez, R. Wildlife Conservation on the Rangelands of Eastern and Southern Africa: Past, Present, and Future. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 71, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindiga, I. Tourism and African Development—Change and Challenge of Tourism in Kenya; African Studies Centre, Research Series, 14/1999; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper, R. Wildlife Watching and Tourism: A Study on the Benefits and Risks of a Fast Growing Tourism Activity and Its Impacts on Species; UNEP/CMS Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel and Tourism Council. The Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism—Travel and Tourism as an Economic Tool for the Protection of Wildlife; World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IUNC. Pastoralism in Ethiopia: Its Total Economic Values and Development Challenges; IUNC—UNEP: Gland, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNECASRO-EA. Ecotourism in the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Region—An Untapped Potential with Considerable Socio-Economic Opportunities; Economic Ommission for Africa Sub-Regional Office for Eastern Africa (SRO-EA), United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Sub-Regional Office for Eastern Africa: Kigali, Rwanda, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Tourism, community-based tourism and ecotourism: A definitional problematic. South Afr. Geogr. J. 2018, 101, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, C.; MacGregor, J. Pastoralism—Africa’s invisible economic powerhouse? World Econ. 2013, 14, 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Krätli, S. If Not Counted Does Not Count? A programmatic reflection on methodology options and gaps in Total Economic Valuation studies of pastoral systems. In IIED Issue Paper; IIED: Londonm, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, R.; Davies, J. A Global Review of the Economics of Pastoralism; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition of European Lobbies on Eastern African Pastoralism. CELEP Position Paper on Recognition of the Role and Value of Pastoralism and Pastoralists; Coalition of European Lobbies on Eastern African Pastoralism: Istanbul, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.; Hatfield, R. The economics of mobile pastoralism: A global summary. Nomadic Peoples 2007, 11, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. WTTC-TTCR Reports 2007–2019; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A. Pastoralism and Development Policy in Ethiopia: A Review Study. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst.-J. 2019, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT-QV Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QV (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Jenet, A.N.; Buono, S.; Di Lello, M.; Gomarasca, C.; Heine, S.; Mason, M.; Nori, R.; Saavedra, K. The Path to Greener Pastures. Pastoralism, the Backbone of the World’s Drylands; Vétérinaires Sans Frontières International (VSF-International): Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN ESARO. The state of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa. In State of Protected and Conserved Areas Report Series; IUCN ESARO: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nyariki, D.M.; Amwata, D.A. The value of pastoralism in Kenya: Application of total economic value approach. Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development. Assessment of the Total Economic Valuation of Pastoralism in Kenya; IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development (ICPALD): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.P.; Hijmans, R.J.; Caro, T. How effective are the protected areas of East Africa? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Database. Economic Data. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/%20NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- World Bank Database. Tourism Arrivals Data. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Okech, R.; Kieti, D.; Duim, V.R. (Eds.) Tourism, Climate Change and Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa (Vol. 46); African Studies Centre Leiden (ASCL): Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Altes, C. Analysis of Tourism Value Chain in Ethiopia—Final Report; CBI-Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Nairobi, Ethiopia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ELCI (Environment Liaison Centre International). Pastoralism as a Conservation Strategy and Contribution in Livelihood Security. Ethiopia Country Study. 2016. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/sites/default/files/import/downloads/ethiopia_country_study.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Wassie, S.B. Natural resource degradation tendencies in Ethiopia: A review. Environ. Syst. Res. 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Liaison Centre International. Pastoralism as a Conservation Strategy and Contributor to Livelihood Security—Kenya Country Study; Environment Liaison Centre International (ELCI): Nairobi, Kenya, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania Natural Resource Forum. Study on Options for Pastoralists to Secure Their Livelihoods. Assessing the Total Economic Value of Pastoralism in Tanzania; Tanzania Natural Resource Forum: Arusha, Tanzania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Denman, R. Guidelines for Community-Based Ecotourism Development. WWF International. 2001. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?12002/Guidelines-for-Community-based-Ecotourism-Development (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- World Bank. Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, B.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Sustainability as a Key Factor in Tourism Competitiveness: A Global Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Michael, N.; Hayes, J.P. Destination competitiveness from a tourist perspective: A case of the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otwori, J.L.; Fredrick, A.G.; Abduletif, A.A.; Dávid, L.D. Kenya’s standard gauge railway project in the context of theory and practice of regional planning. Acta Carolus Robertus 2020, 10, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Akaak, A.; Lakner, Z.; Gyuricza, C.; Dávid, L.D. Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Yan, X.; Alimov, A.; Farmanov, E.; Dávid, L.D. Regional sustainability: Pressures and responses of tourism economy and ecological environment in the Yangtze River basin, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabil, M.; Ali, M.A.; Marzouk, A.; Dávid, L.D. Gender perspectives in tourism studies: A comparative bibliometric analysis in the MENA region. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Purwoko, Y.; Dávid, L.D. Rethinking sustainable community-based tourism: A villager’s point of view and case study in Pampang Village, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, H.; Adol, G.F.C.; Bujdosó, Z.; Benedek, A.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Dávid, L.D. Theoretical Nexus of Knowledge Management and Tourism Business Enterprise Competitiveness: An Integrated Overview. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, H.; El Archi, Y.; Dénes Dávid, L. Current trends in sustainable organization management: A bibliometric analysis. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 11–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).