Abstract

Background: The development of quality education, as stated by the United Nations in the 4th Sustainable Development Goal of the 2030 Agenda, is a very relevant aspect to work on, and specifically, motivation can play an important role. Consequently, the development of intrinsic motivation (IM) in university education and searches for possible interventions have increased exponentially in the last decade. However, no reviews have been published analyzing the interventions and the results obtained. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to systematically analyze the development of IM in online education through the different intervention programs carried out in university teaching. Methods: A systematic review of PubMed, Web of Sciences and Scopus was performed according to PRISMA guidelines. Results: Of the 255 studies initially identified, 17 were thoroughly reviewed, and all interventions and outcomes were extracted and analyzed. Most of the interventions achieved better outcomes after implementation. Five types of possible courses of action to promote IM have been identified. Conclusions: It is worth highlighting the unanimity found regarding the importance of proposing specific approaches based on the development of IM in university online teaching since it promotes satisfaction regarding studying and greater involvement of students.

1. Introduction

The 4th Sustainable Development Goal of the 2030 Agenda [1] highlights the importance of guaranteeing inclusive, egalitarian, high-quality education and encouraging opportunities for lifelong learning for everyone. Quality education is an integral part of sustainable development as it is a key enabler. Consequently, there is a great deal of research on the importance of motivation development in quality education [2,3,4,5]. Much of the scientific community that has worked on motivational interventions have used as its basis self-determination theory [6], which postulates a taxonomy comprising demotivation, extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation (IM). Demotivation is a lack of motivation characterized by being unregulated, impersonal, and associated with a sense of incompetence, a lack of value and perceived contingency [7]. Other research [8,9,10] defines extrinsic motivation as the determination to carry out a specific task or action for some outside motive, where the motivation is connected to students’ perceptions of the worth or significance of their academic work. So extrinsic motivation refers to behavior performed to achieve some specific outcome, external incentives, or rewards. Several studies define IM as the intention to carry out a particular task or action with the understanding that doing so will bring about satisfaction [8,11]. Thus, considered the pinnacle of behavioral self-regulation and individual liberty, IM entails engaging in action out of pure interest and enjoyment [12,13]. In addition, IM has a substantial correlation with achievement, quality education, well-being and student achievement [14]. Most research agrees in differentiating IM from extrinsic motivation in analysing results, obviating demotivation [15,16].

The primary focus of self-determination theory is on internal motivational factors based on the support of the basic psychological needs for growth [6,7,9,17]: autonomy (the desire for autonomy and a sense of responsibility for one’s actions), competence (in which individuals feel effective and capable); and relatedness (in which individuals feel meaningfully connected to or cared for by other individuals and groups). Specifically, based on self-determination theory, there has recently been an increase in studies in education that have aimed to develop IM through specific interventions or programs [4,18,19,20,21]. Some have chosen to synchronize their study materials at any place or time and using any device, which can enhance academic achievement and deepen the teacher-student bond through information sharing [20]; others have taken into account technological, organizational and environmental impacts in their intervention [18]; another intervention seeks the development of competencies through agile methodologies and didactic materials that were created to promote interest in learning, improve attention, and boost IM, enhancing autonomous, active, and self-directed learning [19]. Other lecturers have explored the topic through blogs preparing integrative, innovative, computer-based interactive case studies as learning materials through informal game experiences since they reflect the collaborative skills necessary in educational or professional communities [4,21].

In addition, there is an increasing amount of research in online education highlighting the importance of IM for optimal academic performance. Several recent studies measure IM as a predictive variable for success in online programs [4]. Several of them take into account variables such as a positive attitude towards self, towards others, openness to learning, behavioral autonomy, and educational engagement [4,6,22]; other studies have analyzed in detail the benefit of IM for performance in methodologies such as the flipped classroom [23,24,25]; the correlation between students’ IM and creativity in online education as well as online learning engagement; creativity and perceived teacher emotional support has also been explored, obtaining positive results [6,13,26,27].

Finally, as a consequence, numerous studies can be found that work on interventions for the development of IM in university education and specifically in online education [28,29,30,31].

As can be seen, this is a subject that is highly valued by the scientific community, so it is helpful to be able to bring together the information that is currently available on different interventions that promote IM since, according to the most recent studies, the success of online education depends quite considerably on the students’ own IM. The need for compilation and analysis was the starting point for the present study, which aimed to systematically analyze the development of IM in online education through the different intervention programs carried out at the university level. Thus, it will be possible to obtain current results on the types of intervention being implemented and to draw valuable conclusions for future studies. In particular, this study will be relevant for researchers or university lecturers who seek to achieve an education that allows the development of the full potential of the student’s abilities and satisfaction, as well as academic performance.

2. Materials and Methods

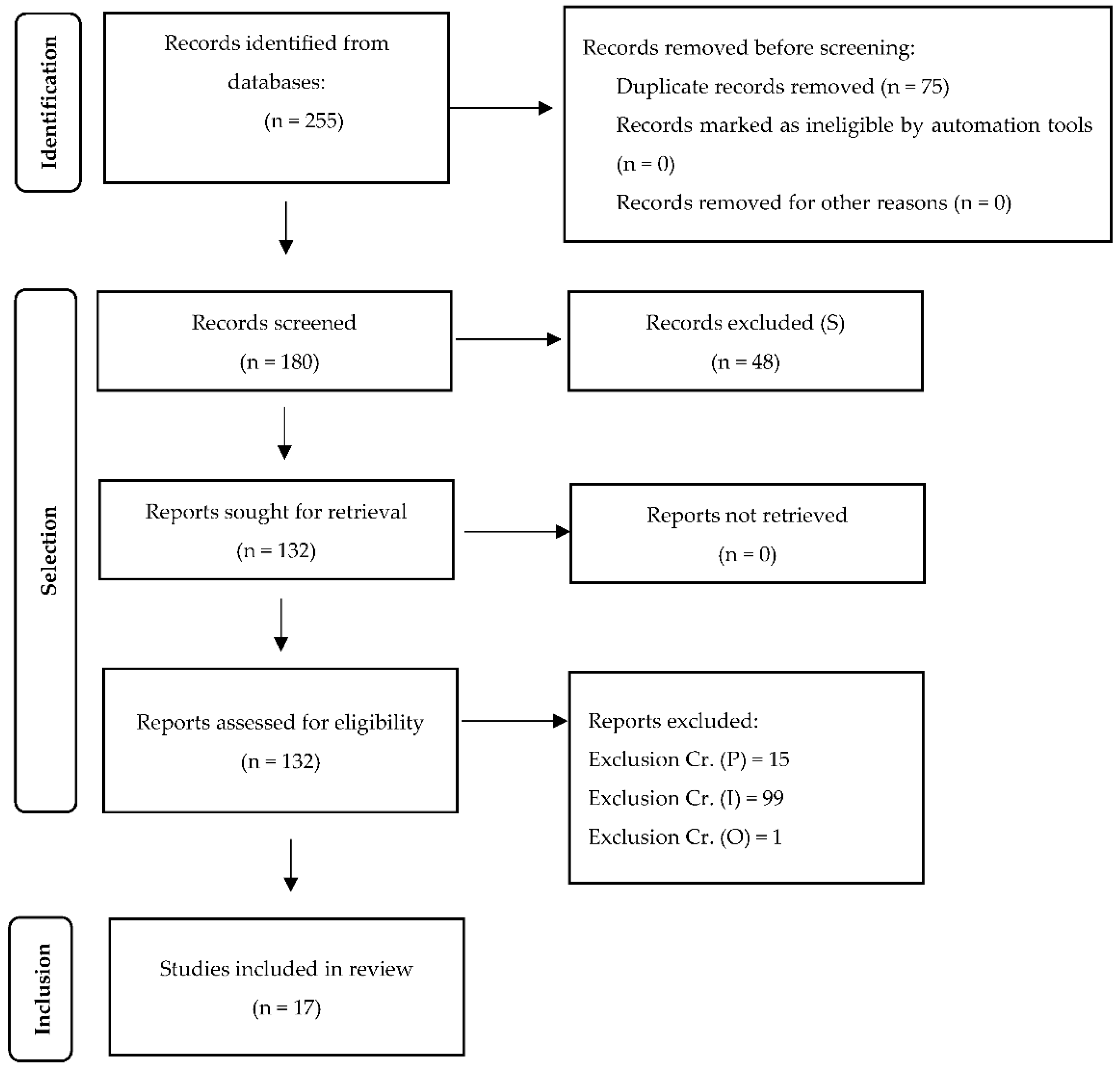

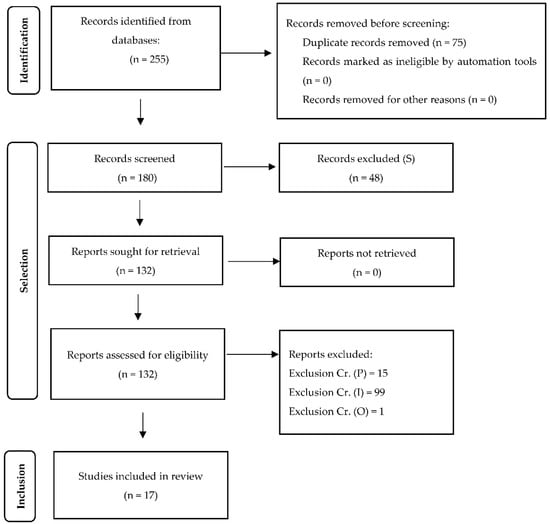

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards were followed for conducting this systematic review [32,33] (Supplementary Table S1). The PRISMA-supported standards guarantee that the publications included have undergone a thorough review process. The four PRISMA-recommended phases are depicted in a flow diagram in Figure 1, along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study in each phase.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

2.1. Design

A systematic search was conducted to identify articles published before 4 April 2023 from PubMed, Web of Sciences, and Scopus databases. The search was performed on title, abstract and keywords, and the search approach included words relating to (1) population, (2) intervention, (3) words related to outcomes. The three groups of keywords were combined using AND, and the terms in each group were linked using OR: population—“university”, “higher education”, “high education”; intervention—“online learning”, “online teaching”, “online education”, “e-learning”, “distance learning” and outcomes—“intrinsic motivation”.

2.2. Screening Strategy and Selection of Scientific Articles

Once the search was completed, duplicate records were eliminated. Then, based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the remaining records were reviewed to verify that they met the criteria, which can be seen below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

2.3. Data Selection

The information gleaned from the original publications were the country, sample, area, intervention, measurement methods, results, and conclusions.

2.4. Methodological Assessment

An adapted version of the STROBE evaluation criteria [34] was used in the methodological evaluation procedure to find appropriate papers for inclusion. Ten specific criteria were used to evaluate each article (see Table 2). Each item was scored using a numerical description (1 = completed, 0 = not completed). According to O’Reilly et al. [33], each study’s rating was qualitatively evaluated in accordance with the following law: studies with scores below seven are deemed to be at high risk of bias, while those with scores above seven are thought to be at low risk.

Table 2.

The methodological quality of the articles.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

75 of the 255 records initially retrieved from the databases were duplicates or triplicates. As a result, 180 articles in total were downloaded. Forty-eight studies were disregarded in accordance with criterion 5 (Study) after the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the remaining publications were examined in accordance with the same criteria. Out of the 132 articles that were left, 15 were eliminated for failing to meet Criterion 1 (Population), 99 were eliminated based on Criterion 2 (Intervention), and one was eliminated based on Criterion 3 (Outcomes). Finally, for the qualitative analysis, 17 studies were included (Figure 1).

3.2. Methodological Quality

Table 2 shows that the overall methodological quality of the articles is very high according to the assessment of each item provided by STROBE evaluation criteria [34]. In addition, a timeline of literature in IM is presented, where the trend of scientific interest in this area can be appreciated and where most of the research is from the last two years (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.3. Article Analysis

The results of the analysis of the articles are shown below, where the most important information regarding the country, sample, area, intervention, methods of measurement, results and conclusions can be observed.

As shown in Table 3, the samples of the studies are broad and representative, and geographically it can be seen that they cover very diverse locations, so the subject of this study is of interest regardless of cultures or teaching methods.

Table 3.

Country, Sample, Area, Intervention, Measurement Methods, Results and Conclusions.

As for interventions aimed at fostering IM, the studies use different strategies, all based on new technologies and the opportunities they offer. Since they are in themselves online programs, so digital tool is present. Thus, some use interactive elements such as quizzes (some of them with badges), multimedia applications and videos, collaborative platforms, mobile applications, gamification, and augmented reality-supported educational escape activity [29,31,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,45]; other interventions are based on encouraging discussion forums or peer feedback mechanisms, or use Chatbot [15,30,38]; other studies have explored more thoroughly the role of the teacher who is committed to giving special importance to teacher support and flexibility, and emphasize the importance of communication and a professional appearance on the part of the instructor [28,44]; other research gives importance to the use of personalized learning activities [34].

With respect to the results of the studies, it can be seen how most of them find that IM has been fostered after the interventions. Studies have concluded that interventions that have been based on encouraging mobile use [29,39,45], cooperation and communication [28,30,31] using online forums, personalized learning [34], integrating certain educational tools [35,38,42] such as quizzes [36,41,43] and in which the teacher supports the students [44] in a meaningful way, have been valuable in fostering IM. On the other hand, strategies such as educational escape rooms based on augmented reality or badges do not seem helpful in encouraging IM [37,40]. Likewise, mandatory or voluntary participation in online discussion forums does not promote the development of IM [15].

4. Discussion

This review’s objective was to carefully examine the growth of IM in online education through the different intervention programs carried out in university teaching. In general terms, it can be stated that the published interventions succeed in promoting IM by following numerous strategies.

Research [39] highlights the importance of using cell phones or tablets to increase students’ IM. The generalized use of these devices and their flexibility makes them constantly accessible from anywhere, and they are very operational. The ease of access and use of the course through cell phones and tablets can be promoted by enhancing the user-friendliness of the applications, with files in different formats, “mobile friendly resources”, or useful apps. These findings are congruent with self-determination theory, which is based on basic psychological needs, specifically, in this case, autonomy and competence, since they favor the need for choice and students feel effective and capable [9].

Other authors highlight the importance of integrating certain tools combining an online course’s pedagogical features and structural substance. Thus, we can find multimedia applications and videos [31,35], quizzes [36,41,43] and teaching videos with chatbot and peer feedback mechanisms [38]. In addition, gamification can be a very appropriate element to enhance experiences and increase student interest. Specifically, quizzes contain various types of questions. They are a useful tool for reviewing and remembering essential ideas and concepts in an engaging and fun way, thus promoting learner curiosity and attention. In addition, they help to improve participation by encouraging students’ competitiveness, inspired by the desire to rank among the top players in the game. The quizzes can be repeated as many times as the student wishes, thus allowing control of the pace of learning. These tools are, therefore, very interesting support for IM in online teaching.

In contrast, using an educational platform with videos and other materials does not always increase intrinsic achievement motivation [35]. It is very important that they should be very well designed, with a correct selection of educational materials and that the videos are made at a high technical level. Once again, it can be observed that the self-determination theory and, in particular, the aspects of autonomy and competence can justify the success of these proposals since the students have freedom in the tasks and can test their capacity [7].

Other strategies consider it essential to encourage cooperation and communication activities among online students. The research considers that these interactions not only promote learning [34], but also foster friendship among students, which is beneficial for reducing student anxiety and stress [31]. Thus, we consider that a correct design of group discussion techniques is essential to encourage student interactions and make them productive. To this end, one study [30] shows that discussions in the course online forum should have less than 150 students to be effective since this avoids “mass features”. Therefore, a basis can be found in self-determination theory that supports the importance of the basic psychological need for relatedness where students feel connected to each other [17].

Other lines of research advocate giving a more relevant role to the teacher’s work from different perspectives. The support of tutors in a focused and proactive way are aspects that favor student motivation [44]; understood as the way in which the teacher supports and can offer more personal teaching or in which the students feel that they go hand in hand with the teacher and feel cared for, which can be supported by the self-determination theory, and, in particular, by the need for relatedness where students feel cared for by other individuals, and in this case by the teacher [6]. In addition, the teacher should offer a professional appearance and communication [28]. In this regard, a professional appearance is based on dress styles, such as wearing a suit and using certain colors. Professional communication is equivalent to the linguistics used, such as, for example, connecting words and a speech without hesitant pauses. In addition, the way in which the communicators emphasize the speech or address the students, involving them in what the communicators are transmitting, are factors that can favor listening.

Other strategies that can help to increase IM may refer to personalized learning since we live in a plural society, where the student profile can be very varied and very diverse casuistry can be found. Thus, the pace of learning and the teaching approach will be determined based on the needs of each student. Along these lines, [34] learning objectives, teaching instructional approaches, teaching content and sequence, and learning activities can be personalized. In this way, learners can choose from certain pre-established learning paths to complete the course. In this case, as supported by the self-determination theory, competence is favored since the student can focus and feel more effective in his work [7].

Finally, it should be noted that other interventions aimed at promoting intrinsic motivation have not found significant differences (for example, interventions based on augmented reality supported educational escape activity [37], but others have been useful in promoting other aspects, such as extrinsic motivation [15,45]. Finally, a badges study has shown that IM has decreased [40].

In general terms, it is worth mentioning that interventions designed to promote IM must comply with the following aspects:

- -

- Easily accessible technologically, friendly from any device.

- -

- Very well designed from a curricular point of view, using various educational supports such as quizzes, videos and attractive presentations and discussion forums where students can interact with each other.

- -

- Adapted to the contents favoring effective learning and personalizing education.

- -

- Teachers must know the students well to consider their needs or preferences to support the learning process professionally.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

5.1. Conclusions

It is worth highlighting the unanimity found regarding the importance of proposing specific approaches based on the development of IM in university online teaching since it promotes satisfaction towards studying and greater involvement on the part of students. Specifically, there is an increasing presence in universities of online training programs for different university degrees, so this teaching modality is booming and has a future that will have more and more presence.

Moreover, it is worth underlining the role of integrating new technologies in the classroom since they allow the teacher to make the most of the resources available. Thus, the most varied interventions have been found, all to promote the IM of online university students, in which they have been able to advance through multiple strategies. The use of cell phones or tablets and their accessibility has been highlighted, as well as the incorporation of multimedia applications or quizzes. It has also been seen that it is essential to encourage cooperation and communication among students through discussion forums or with the teacher, who can play a key role in flexibility and professionalism, as well as the personalization of teaching in a society as plural as it is today, with such varied student profiles.

It is essential to implement suitable interventions that promote IM to achieve quality education. In this way, the intervention can contribute to the development of the 4th Sustainable Development Goal of the 2030 Agenda. This goal emphasizes the significance of delivering inclusive and equitable quality education and encouraging opportunities for lifelong learning for everyone [1].

The present study could be limited by the fact that although the most relevant databases have been included, it is possible that some other articles could be found in other databases.

5.2. Future Directions

This systematic review can be the starting point for future studies since the scientific community has shown that the development of IM within the university context is a highly relevant topic that is still in full development and has a long way to go. In addition, the interest shown in such diverse geographical locations provides clear evidence that it is a theme that can be applied regardless of culture or methodologies. Finally, the work of fostering IM in online students and the interventions can be varied, making it a perfect field for creating and innovating following the guidelines outlined in this review and achieving a much more engaging future education with new tools thanks to technological advances that enhance the development of the student’s full potential and quality education as stated by the United Nations in the 4th Sustainable Development Goal.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su15139862/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist; Figure S1: Timeline of literature in IM (number of articles per year). Reference [46] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.A. and A.V.; methodology, R.K.A. and M.C.M.-M.; formal analysis, R.K.A. and M.C.M.-M.; investigation, A.V.; data curation, R.K.A. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.A. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.V. and M.C.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Giangrande, N.; White, R.M.; East, M.; Jackson, R.; Clarke, T.; Saloff Coste, M.; Penha-Lopes, G. A Competency Framework to Assess and Activate Education for Sustainable Development: Addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals 4.7 Challenge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Frías, E.; Arquero, J.L.; Del Barrio-García, S. Exploring How Student Motivation Relates to Acceptance and Participation in MOOCs. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. Contemporary American Literature in Online Learning: Fostering Reading Motivation and Student Engagement. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4725–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Lio, A.; Dhaliwal, H.; Andrei, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Nagani, U.; Samadder, S. Psychological Interventions of Virtual Gamification within Academic Intrinsic Motivation: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; Sanmartín, R.; Inglés, C.J.; García-Fernández, J.M. Academic Goal Profiles and Learning Strategies in Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Ringer, A.; Saville, K.; Parris, M.A.; Kashi, K. Students’ Motivation and Engagement in Higher Education: The Importance of Attitude to Online Learning. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, I.M.; Kusurkar, R.A. Science-Writing in the Blogosphere as a Tool to Promote Autonomous Motivation in Education. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 35, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Information Literacy and Recent Graduates: Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Perception of Credit-Based Information Literacy Courses. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2023, 49, 102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y. Students’ Motivation and Continued Intention with Online Self-Regulated Learning: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Z. Erzieh. 2021, 24, 1379–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, R.K.; Pozériene, J. Academic Motivation among Traditional and Online University Students. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2020, 9, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluce, A.C.; Oliveira, K.L.D. Students’ Motivation for Learning in Virtual Learning Environments. Paidéia 2015, 25, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, A.; Koestner, R. A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on How to Choose, Use, and Lose Personal Goals. In The Oxford Handbook of Educational Psychology; O’Donnell, A., Barnes, N.C., Reeve, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-19-984133-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bochiş, L.N.; Barth, K.M.; Florescu, M.C. Psychological Variables Explaining the Students’ Self-Perceived Well-Being in University, during the Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaid Mohammed Ali, J. The Impact of Online Learning amid COVID-19 Pandemic on Student Intrinsic Motivation and English Language Improvement. Dirasat Hum. Soc. Sci. 2022, 49, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Distance Education: A Self-Determination Perspective. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Li, R. Understanding Chinese Teachers’ Informal Online Learning Continuance in a Mobile Learning Community: An Intrinsic–Extrinsic Motivation Perspective. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajlouni, A.; Rawadieh, S.; Almahaireh, A.; Awwad, F.A. Gender Differences in the Motivational Profile of Undergraduate Students in Light of Self-Determination Theory: The Case of Online Learning Setting. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2022, 1, 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, F.; Xiu, G.; Khan, I.; Shahbaz, M.; Riaz, M.U.; Abbas, A. The Moderating Role of Intrinsic Motivation in Cloud Computing Adoption in Online Education in a Developing Country: A Structural Equation Model. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 2020, 21, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales-Ronda, P.; Aragonés-Jericó, C. Agile Methodologies in Times of Pandemic: Acquisition of Employment Skills in Higher Education. ET 2022, 64, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinsorgen, C.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M.; Naim, H.Y.; Branitzki-Heinemann, K.; Kankofer, M.; Mándoki, M.; Adler, M.; Tipold, A.; Ehlers, J.P. Impact of Virtual Patients as Optional Learning Material in Veterinary Biochemistry Education. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2018, 45, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilak, S.; Glassman, M.; Peri, J.; Xu, M.; Kuznetcova, I.; Gao, L. Need Satisfaction and Collective Efficacy in Undergraduate Blog-Driven Classes: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado Cespón, M.; Díaz Lage, J.M. Gamification, Online Learning and Motivation: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis in Higher Education. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2022, 14, ep381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Mesa, M.-C.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C.; DelCastillo-Andrés, Ó.; González-Campos, G. Augmented Reality and the Flipped Classroom—A Comparative Analysis of University Student Motivation in Semi-Presence-Based Education Due to COVID-19: A Pilot Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan Yılmaz, F.G. An Investigation into the Role of Course Satisfaction on Students’ Engagement and Motivation in a Mobile-assisted Learning Management System Flipped Classroom. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2022, 31, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; López-González, E. Impacto de La Clase Invertida En La Percepción, Motivación y Rendimiento Académico de Estudiantes Universitarios. Form. Univ. 2021, 14, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Y.; Thompson, P. Flipped University Class: A Study of Motivation and Learning. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. Student Intrinsic Motivation for Online Creative Idea Generation: Mediating Effects of Student Online Learning Engagement and Moderating Effects of Teacher Emotional Support. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 954216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beege, M.; Krieglstein, F.; Arnold, C. How Instructors Influence Learning with Instructional Videos—The Importance of Professional Appearance and Communication. Comput. Educ. 2022, 185, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.B. The Use of Mobile Devices in University Distance Learning: Do They Motivate the Students and Affect the Learning Process? Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, H.; Buyuk, K. Examination of Online Group Discussions in Terms of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Presence, and Perceived Learning. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2022. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Tian, M.; Fan, J.; Sun, Y. Influences of Online Learning Environment on International Students’ Intrinsic Motivation and Engagement in the Chinese Learning. J. Int. Stud. 2022, 12, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, M.; Caulfield, B.; Ward, T.; Johnston, W.; Doherty, C. Wearable Inertial Sensor Systems for Lower Limb Exercise Detection and Evaluation: A Systematic Review. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 1221–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, H.; Lowell, V.; Watson, W.; Watson, S.L. Using Personalized Learning as an Instructional Approach to Motivate Learners in Online Higher Education: Learner Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 52, 322–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berestova, A.; Burdina, G.; Lobuteva, L.; Lobuteva, A. Academic Motivation of University Students and the Factors That Influence It in an E-Learning Environment. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2022, 20, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, C.; Ghebremedhin, E.; Hansen, M. Development of an Interactive E-Learning Software “Histologie Für Mediziner” for Medical Histology Courses and Its Overall Impact on Learning Outcomes and Motivation. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2020, 37, Doc35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elford, D.; Lancaster, S.J.; Jones, G.A. Fostering Motivation toward Chemistry through Augmented Reality Educational Escape Activities. A Self-Determination Theory Approach. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 3406–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, M.; Gencel, N. Supporting the Instructional Videos With Chatbot and Peer Feedback Mechanisms in Online Learning: The Effects on Learning Performance and Intrinsic Motivation. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 60, 1716–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeno, L.M.; Grytnes, J.-A.; Vandvik, V. The Effect of a Mobile-Application Tool on Biology Students’ Motivation and Achievement in Species Identification: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Comput. Educ. 2017, 107, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyewski, E.; Krämer, N.C. To Gamify or Not to Gamify? An Experimental Field Study of the Influence of Badges on Motivation, Activity, and Performance in an Online Learning Course. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadán-Díaz, M.; Rivas-García, J.I. Percepciones de los estudiantes de posgrado ante la gamificación del aula con Quizizz. Texto Livre 2022, 15, e36941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, F.; Batooli, Z. Design, Development, and Evaluation of an Online Tutorial for “Systematic Searching in PubMed and Scopus” Based on GOT-SDT Framework. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2021, 47, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.M.; Fleming, R.; Pedrick, L.E.; Jirovec, D.L.; Pfeiffer, H.M.; Ports, K.A.; Barnack-Tavlaris, J.L.; Helion, A.M.; Swain, R.A. U-Pace instruction: Improving student success by integrating content mastery and amplified assistance. Online Learn. 2013, 17, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.; Leverett, S.; Beaumont, K. Success of Distance Learning Graduates and the Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learn. 2020, 35, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhko, Z.; Babaskin, D.; Vanina, E.; Rogulin, R.; Egorova, Z. Motivation for Mobile Learning: Teacher Engagement and Built-In Mechanisms. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2022, 16, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).