How Underlying Attitudes Affect the Well-Being of Travelling Pilgrims—A Case Study from Lhasa, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

4. Data Sources and Variable Determination

5. Results

5.1. Factor Analysis

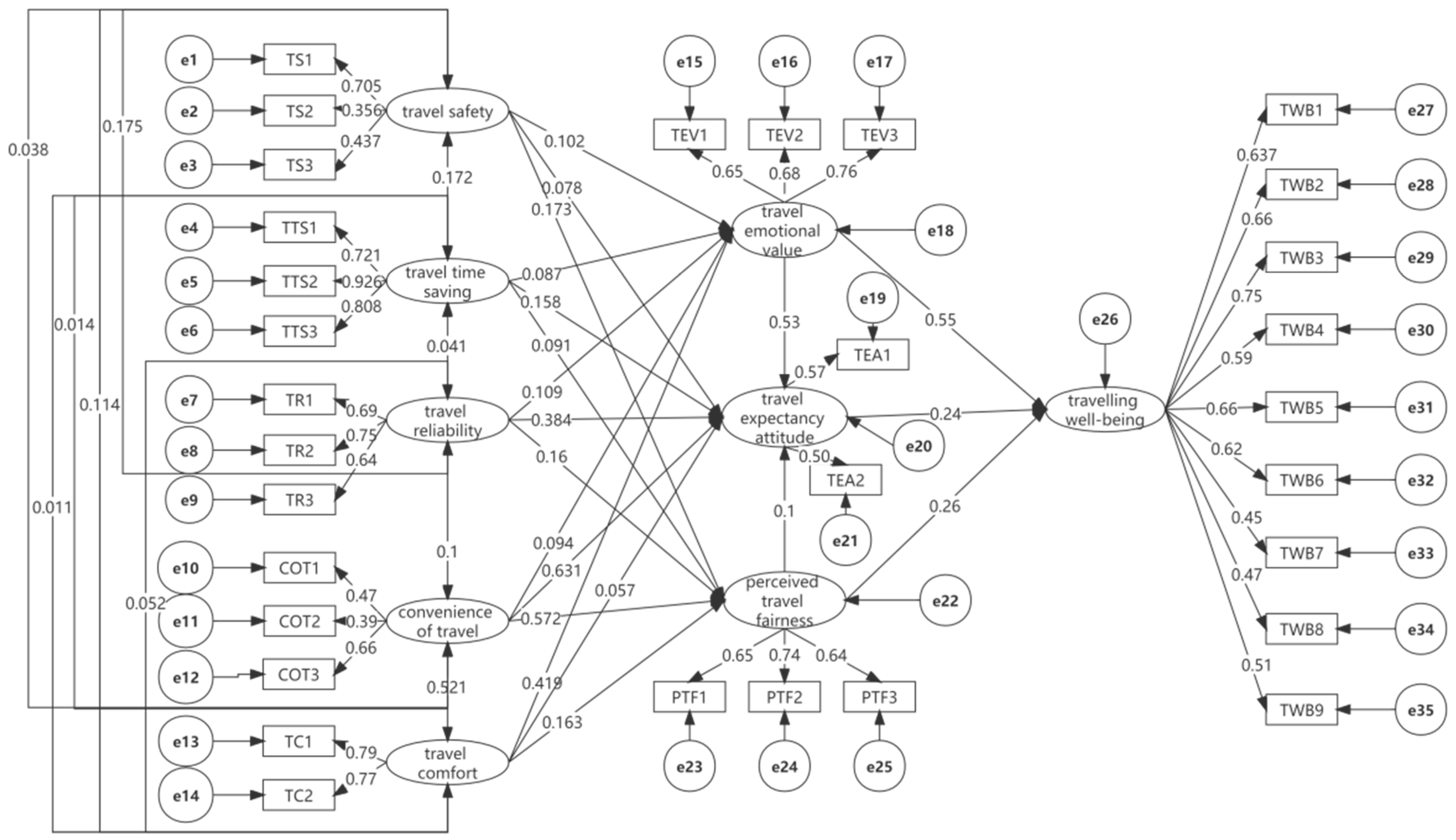

5.2. Model Results

5.3. Travel Market Segmentation Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.; Fan, Y. Review of Overseas Studies on Subjective Well-being During Travel and Implications for Future Research in China. Urban Plan. Int. 2018, 33, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M. Social indicators of perceived life quality. Soc. Indic. Res. 1974, 1, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Developments in satisfaction-research. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 37, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Fujita, F. Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. the science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, S.; Singh, P. Psychological well-being and pilgrimage: Religiosity, happiness and life satisfaction of Ardh–Kumbh Mela pilgrims (Kalpvasis) at Prayag, India. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 12, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; El-Geneidy, A.M. Does distance matter? exploring the links among values, motivations, home location, and satisfaction in walking trips. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 50, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Titheridge, H. Satisfaction with the commute: The role of travel mode choice, built environment and attitudes. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Cai, L.A.; Li, M. Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kwon, J. A study on fairness perception, relation quality and long-term orientation of travel business franchise. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 28, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Carrel, A.; Mishalani, R.G.; Sengupta, R.; Walker, J.L. In pursuit of the happy transit rider: Dissecting satisfaction using daily surveys and tracking data. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 20, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzer, A.; Frey, B.S. Stress that doesn’t pay: The commuting paradox. Scand. J. Econ. 2008, 110, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorée, D. The 3p model: A general theory of subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 681–716. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, C.D.; Sweet, M.N.; Kanaroglou, P.S. All minutes are not equal: Travel time and the effects of congestion on commute satisfaction in canadian cities. Transportation 2017, 45, 1249–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaco, R.W.; Stokols, D.; Milanesi, L. Objective and subjective dimensions of travel impedance as determinants of commuting stress. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susilo, Y.O.; Cats, O. Exploring key determinants of travel satisfaction for multi-modal trips by different traveler groups. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 67, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Schwanen, T.; Van Acker, V.; Witlox, F. Travel mode choice and travel satisfaction: Bridging the gap between decision utility and experienced utility. Transportation 2016, 43, 771–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstad, C.J.; Gamble, A.; Gärling, T.; Hagman, O.; Polk, M.; Ettema, D.; Olsson, L.E. Subjective well-being related to satisfaction with daily travel. Transportation 2011, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Schwanen, T.; Van Acker, V.; Witlox, F. Travel and Subjective Well-Being: A Focus on Findings, Methods and Future Research Needs. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Herstein, R.; Caber, M.; Drori, M.; Bideci, M. Exploring religious tourist experiences in Jerusalem: The intersection of Abrahamic religions. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.; Raj, R. The importance of religious tourism and pilgrimage: Reflecting on definitions, motives and data. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2018, 5, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Golob, T.F. Joint models of attitudes and behavior in evaluation of the san diego i-15 congestion pricing project. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2001, 35, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Richardson, T.; Smyth, P.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hine, J.; Lucas, K. Investigating links between transport disadvantage, social exclusion and well-being in melbourne-updated results. Res. Transp. Econ. 2010, 29, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Choe, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.; Pae, T.I. The effects of pilgrimage on the meaning in life and life satisfaction as moderated by the tourist’s faith maturity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Vella-Brodrick, D. The usefulness of social exclusion to inform social policy in transport. Transp. Policy 2009, 16, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, X.W. Activity-travel behavior model of urban low-income commuters based on structural equation. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 45, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E.A.; Guerra, E. Mood and mode: Does how we travel affect how we feel? Transportation 2015, 42, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, D.A.; Wiesenthal, D.L. The relationship between traffic congestion, driver stress and direct versus indirect coping behaviours. Ergonomics 1997, 40, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zeid, M.; Ben-Akiva, M. The effect of social comparisons on commute well-being. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, D.T.; Mokhtarian, P.L. When is getting there half the fun? modeling the liking for travel. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseki, H.; Taylor, B.D. Not all transfers are created equal: Towards a framework relating transfer connectivity to travel behaviour. Transp. Rev. 2009, 29, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Evaluating transportation equity. World Transp. Policy Pract. 2002, 8, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Willson, G.B.; McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A.L. Tourism and spirituality: A phenomenological analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, C.; Carnegie, E. Pilgrimage: Journeying beyond self. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, Z. Travel behavior characteristics of pilgrimage groups in Lhasa under age differences. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 4, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ettema, D.; Garling, T.; Eriksson, L.; Friman, M.; Olsson, L.E.; Fujii, S. Satisfaction with travel and subjective well-being: Development and test of a measurement tool. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D.; Friman, M.; Garling, T.; Olsson, L.E.; Fujii, S. How in-vehicle activities affect work commuters’ satisfaction with public transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Tatham, R.L.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate data analysis. Technometrics 1998, 30, 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Latent Variables | Indicators |

|---|---|

| TS | TS1: The planning of travel routes ensures the safety of travellers. |

| TS2: The mode of travel used is safe. | |

| TS3: The infrastructure is in place to ensure that travellers can carry out their activities in an orderly manner. | |

| TTS | TTS1: Short time to access transport resource services. |

| TTS2: Short time to destination. | |

| TTS3: Short time spent on congested roads. | |

| TR | TR1: Ability to control the travel time. |

| TR2: Ability to know exactly how long it will take to reach the destination. | |

| TR3: Ability to arrive at the destination on time. | |

| COT | COT1: Easy access to the different modes of travel. |

| COT2: Access to different modes of transport. | |

| COT3: Fewer transfers required to reach destination. | |

| TC | TC1: Ability to travel in a quieter environment. |

| TC2: A spacious and uncrowded travel environment during travel. | |

| TEV | TEV1: Stability and comfort during the trip, as expected. |

| TEV2: Transport infrastructure provides understanding and respect for the travelling public during the journey. | |

| TEV3: Reduces fatigue and negative emotions during travel. | |

| TEA | TEA1: Satisfied with travel patterns and optimistic about the future of travel. |

| TEA2: Consider their travel situation to be in an advantageous position to complete their trip as planned. | |

| PTF | PTF1: There are enough ways to travel to ensure that most residents can make the pilgrimage daily. |

| PTF2: Ensuring equal access to travel opportunities for the community. | |

| PTF3: Transportation resources are inclusive and tailored to the individual. |

| Latent Variables | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Emotional dimension | TWB1: Overall, a sense of well-being experienced from the pilgrimage. |

| TWB2: The process and the goal of a pilgrimage is full of meaning. | |

| TWB3: Inner peace and relaxation during the pilgrimage. | |

| TWB4: Active and interested in the pilgrimage. | |

| TWB5: Optimistic about the pilgrimage travel process. | |

| TWB6: Pilgrimage trips are an important part of life, and the respondents feel confident in their ability to complete these activities. | |

| Cognitive level | TWB7: The trip was better than initially expected. |

| TWB8: Enjoying good travel conditions during the trip. | |

| TWB9: The overall travel for the pilgrimage was very smooth. |

| Hypothetical Path | Hypothesis Description |

|---|---|

| H1 | Travel security has a positive impact on emotional values. |

| H2 | Travel security has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H3 | Travel security has a positive impact on perceptions of fairness. |

| H4 | Time-saving travel has a positive impact on emotional value. |

| H5 | Time-saving travel has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H6 | Time-saving has a positive impact on perceptions of fairness. |

| H7 | Convenience of travel has a positive impact on perceptions of fairness. |

| H8 | Convenience of travel has a positive impact on emotional value. |

| H9 | Convenience of travel has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H10 | Travel reliability has a positive impact on perceptions of fairness. |

| H11 | Travel reliability has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H12 | Travel reliability has a positive impact on emotional value. |

| H13 | Travel comfort has a positive impact on perceptions of fairness. |

| H14 | Travel comfort has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H15 | Travel comfort has a positive impact on emotional value. |

| H16 | Perceived travel fairness has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H17 | Emotional value has a positive impact on expected attitudes. |

| H18 | Perception of fairness has a positive impact on travel well-being. |

| H19 | Expected attitudes has a positive impact on travel well-being. |

| H20 | Emotional value has a positive impact on travel well-being. |

| Latent Variable | Observation Variables | Standard Load | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | TS1 | 0.846 | 0.771 | 0.8643 | 0.6801 |

| TS2 | 0.849 | ||||

| TS3 | 0.777 | ||||

| TTS | TTS1 | 0.879 | 0.858 | 0.9325 | 0.8224 |

| TTS2 | 0.991 | ||||

| TTS3 | 0.844 | ||||

| TC | TC1 | 0.812 | 0.758 | 0.7959 | 0.661 |

| TC2 | 0.814 | ||||

| TR | TR1 | 0.746 | 0.787 | 0.7359 | 0.4829 |

| TR2 | 0.710 | ||||

| TR3 | 0.623 | ||||

| COT | COT1 | 0.602 | 0.735 | 0.6977 | 0.4371 |

| COT2 | 0.624 | ||||

| COT3 | 0.748 | ||||

| TEA | TEA1 | 0.799 | 0.710 | 0.7537 | 0.605 |

| TEA2 | 0.756 | ||||

| TEV | TEV1 | 0.736 | 0.720 | 0.8111 | 0.5891 |

| TEV2 | 0.805 | ||||

| TEV3 | 0.760 | ||||

| PTF | PTF1 | 0.712 | 0.755 | 0.7989 | 0.5706 |

| PTF2 | 0.733 | ||||

| PTF3 | 0.817 | ||||

| TWB | TWB1 | 0.742 | 0.809 | 0.8848 | 0.4625 |

| TWB2 | 0.672 | ||||

| TWB3 | 0.748 | ||||

| TWB4 | 0.553 | ||||

| TWB5 | 0.677 | ||||

| TWB6 | 0.637 | ||||

| TWB7 | 0.755 | ||||

| TWB8 | 0.681 | ||||

| TWB9 | 0.630 |

| TS | TTS | TC | TR | COT | TEA | TEV | PTF | TWB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | 0.825 | ||||||||

| TTS | −0.071 | 0.906 | |||||||

| TC | 0.05 | 0.007 | 0.507 | ||||||

| TR | 0.063 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.695 | |||||

| COT | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.257 | 0.004 | 0.813 | ||||

| TEA | 0.029 | 0.051 | 0.032 | 0.116 | 0.094 | 0.778 | |||

| TEV | 0.04 | 0.033 | 0.244 | 0.029 | 0.118 | 0.001 | 0.768 | ||

| PTF | 0.052 | 0.026 | 0.225 | 0.048 | 0.227 | 0.024 | 0.099 | 0.755 | |

| TWB | 0.031 | 0.034 | 0.191 | 0.061 | 0.177 | 0.069 | 0.147 | 0.200 | 0.680 |

| Path | Path Coefficient | p | Standardisation | CR | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS→TEV | 0.119 | 0.208 | 0.102 | 1.259 | H1: Accepted |

| TS→TEA | 0.085 | 0.488 | 0.078 | 0.693 | H2: Rejected |

| TS→PTF | 0.183 | *** | 0.173 | 2.176 | H3: Accepted |

| TTS→TEV | 0.07 | 0.134 | 0.087 | 1.497 | H4: Rejected |

| TTS→TEA | 0.119 | ** | 0.158 | 2.009 | H5: Accepted |

| TTS→PTF | 0.067 | ** | 0.091 | 1.787 | H6: Accepted |

| COT→PTF | 0.543 | *** | 0.566 | 6.619 | H7: Accepted |

| COT→TEV | 0.096 | 0.254 | 0.092 | 1.189 | H8: Rejected |

| COT→TEA | 0.607 | *** | 0.616 | 3.904 | H9: Accepted |

| TR→PTF | 0.114 | *** | 0.131 | 1.884 | H10: Accepted |

| TR→TEA | 0.329 | *** | 0.370 | 2.848 | H11: Accepted |

| TR→TEV | 0.086 | 0.225 | 0.091 | 1.222 | H12: Rejected |

| TC→PTF | 0.130 | *** | 0.188 | 2.653 | H13: Accepted |

| TC→TEA | 0.045 | 0.635 | 0.063 | 0.545 | H14: Rejected |

| TC→TEV | 0.324 | *** | 0.431 | 5.026 | H15: Accepted |

| PTF→TEA | 0.546 | *** | 0.531 | −3.527 | H16: Accepted |

| TEV→TEA | 0.096 | 0.361 | 0.101 | −1.003 | H17: Rejected |

| PTF→TWB | 0.556 | *** | 0.553 | 7.687 | H18: Accepted |

| TEA→TWB | 0.239 | *** | 0.244 | 3.249 | H19: Accepted |

| TEV→TWB | 0.237 | *** | 0.257 | 4.272 | H20: Accepted |

| Attitudinal Factor | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived safety | 3.09 £ | 3.27 £ | 3.08 £ | 2.93 £ |

| Time saving perception | 3.42 £ | 2.01 | 1.95 | 3.66 * |

| Comfort perception | 2.06 | 3.98 * | 2.66 £ | 3.7 * |

| Reliability perception | 3.4 £ | 3.15 £ | 3.54 £ | 3.41 £ |

| Perceived convenience | 3.02 £ | 4.01 * | 3.31 £ | 3.82 * |

| C1 (142/466) | C2 (132/466) | C3 (118/466) | C4 (74/466) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 69 | 76 | 39 | 41 |

| Female | 72 | 55 | 78 | 32 |

| Percentage of women | 51.1% | 42% | 66.7% | 43.8% |

| Age | ||||

| Under 34 years old | 36 | 47 | 21 | 18 |

| 35–54 years old | 37 | 40 | 29 | 32 |

| 55–64 years old | 38 | 32 | 50 | 24 |

| Over 65 years old | 31 | 13 | 18 | 0 |

| Percentage of people over 65 years old | 24.8% | 0.1% | 11.1% | 0% |

| Disposable income | ||||

| <CNY 2000 | 22 | 30 | 18 | 18 |

| CNY 2000–5000 | 66 | 50 | 60 | 30 |

| CNY 5000–7000 | 20 | 38 | 15 | 23 |

| >CNY 7000 | 34 | 14 | 25 | 3 |

| Percentage of population with disposable income less than CNY 2000 | 15.5% | 22.7% | 15.3% | 24.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, G.; Wang, J. How Underlying Attitudes Affect the Well-Being of Travelling Pilgrims—A Case Study from Lhasa, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411268

Cheng G, Wang J. How Underlying Attitudes Affect the Well-Being of Travelling Pilgrims—A Case Study from Lhasa, China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411268

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Gang, and Jiayao Wang. 2023. "How Underlying Attitudes Affect the Well-Being of Travelling Pilgrims—A Case Study from Lhasa, China" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411268

APA StyleCheng, G., & Wang, J. (2023). How Underlying Attitudes Affect the Well-Being of Travelling Pilgrims—A Case Study from Lhasa, China. Sustainability, 15(14), 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411268