Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pandemic Contextualization and Study Population

1.2. Identifying the Research Question

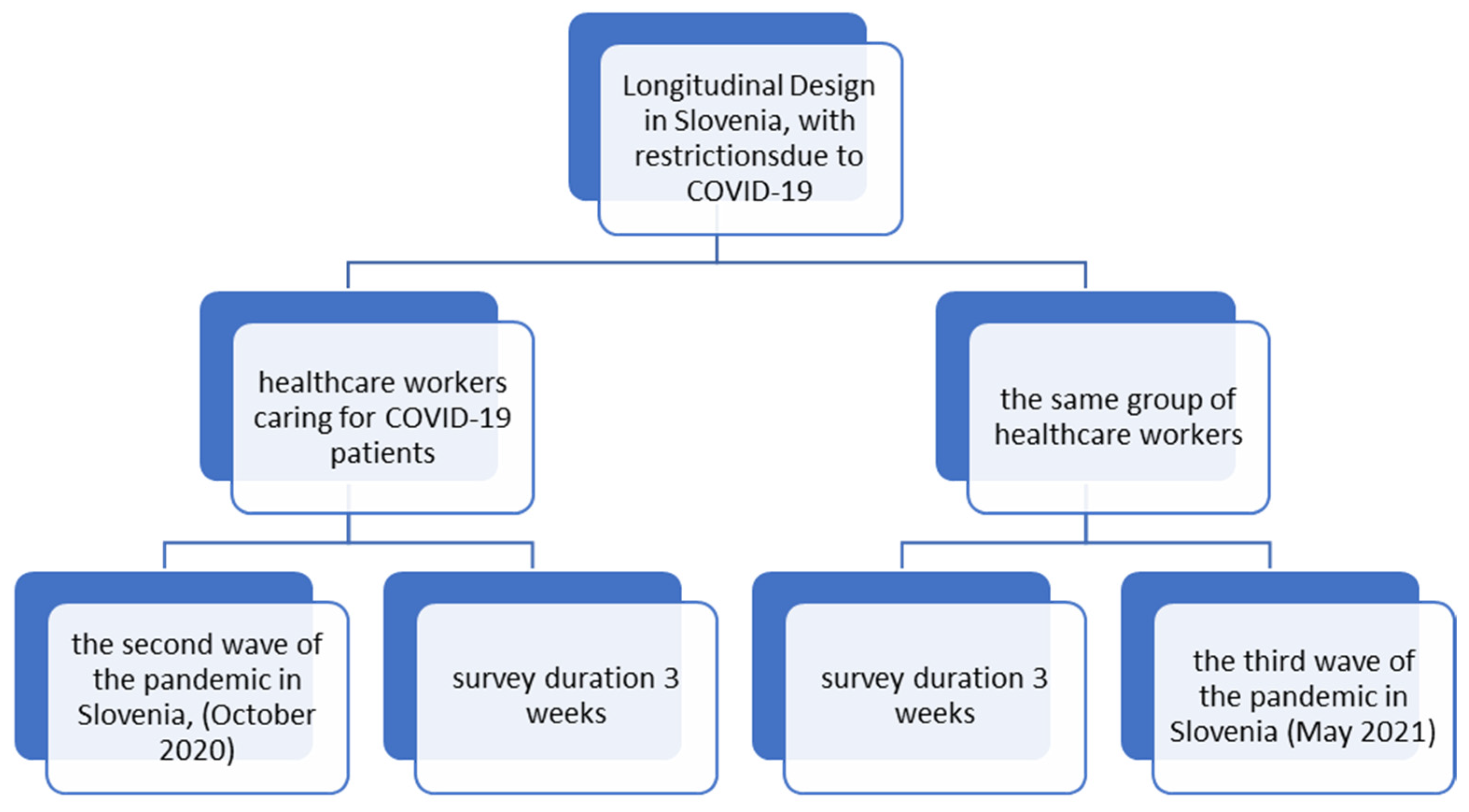

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Recommendations

- Real-time and constant information and involvement of all employees in the planning and implementation of healthcare activities;

- Providing support and assistance in times of crisis and during the emergence of fear (employees must be informed about the person in charge of offering support, as well as all necessary documentation);

- Providing adequate and sufficient protective equipment;

- Promoting effective communication and cooperation between employees;

- Workload and capacity have to be in balance;

- Constant monitoring of well-being and the presence of possible burnout symptoms in employees;

- Awareness that inadequate resources and a lack of autonomy and control of feelings impact one’s ability to succeed at our present and future actions;

- A feeling of fairness at work can be improved if employees feel valued and recognized for the contributions they make;

- It is important to recognize highly demanding (cognitively, emotionally, or physically) tasks;

- Taking time for oneself is crucial for well-being and will benefit the individual’s performance;

- It is important to recognize times when someone is most stressed or anxious;

- All members of healthcare teams must be aware of the symptoms and signs of burnout among colleagues and promote early recognition.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Yıldırım, M.; Geçer, E.; Akgül, Ö. The impacts of vulnerability, perceived risk, and fear on preventive behaviours against COVID-19. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.G.; Walls, R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 1439–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, D. Occupational risks for COVID-19 infection. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Jin, X.; Wei, G.; Chang, C.-T. Monitoring and Early Warning of SMEs’ Shutdown Risk under the Impact of Global Pandemic Shock. Systems 2023, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. The influencing factors of career adaptability of newcomers: Based on multiple perspectives of individual, family and school. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 11, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, M. Comparison of Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among People Affected by versus People Unaffected by Quarantine During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e924609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanos, K.; Mazeri, S.; Constantinou, D.; Vavlitou, A.; Karaiskakis, M.; Kourouzidou, D.; Nikolaides, C.; Savvidou, N.; Katsouris, S.; Koliou, M. Exploring the factors associated with the mental health of frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, S.L.; Johnson, J.; Eades, O.; Cameron, P.A.; Forbes, A.; Fisher, J.; Grantham, K.; Hodgson, C.; Hunter, P.; Kasza, J.; et al. Mental Health Outcomes in Australian Healthcare and Aged-Care Workers during the Second Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhu, X.; Fu, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, J. Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: A multi-center cross-sectional survey investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno Ferrán, M.; Barrientos-Trigo, S. Caring for the caregiver: The emotional impact of the coronavirus epidemic on nurses and other health professionals. Enferm. Clin. Engl. Ed. 2021, 31, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiri, M.; Nargesian, A.; Dastpish, F.; Sharifi, S.M. The impact of psychological capital on mental health among Iranian nurses: Considering the mediating role of job burnout. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrogante, O.; Aparicio-Zaldivar, E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: The mediational role of resilience. Intensive. Crit. Care. Nurs. 2017, 42, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Still, M. Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maben, J.; Bridges, J. Covid-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Qian, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R.; Qi, L.; Yang, J.; Song, X.; Zhou, X.; et al. The prevalence and risk factors of psychological disturbances of frontline medical staff in china under the COVID-19 epidemic: Workload should be concerned. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Smith, C.D.; Hingle, S.; Poplau, S.; Miranda, R.; Freese, R.; Palamara, K. Evaluation of Work Satisfaction, Stress, and Burnout Among US Internal Medicine Physicians and Trainees. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2018758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Xia, Z.; Tao, J. Humanization of nature: Testing the influences of urban park characteristics and psychological factors on collegers’ perceived restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 79, 127806. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G.; Yıldırım, M.; Wong, P.T.P. Meaningful living, resilience, affective balance, and psychological health problems during COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 71, 7812–7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Gong, X.; Liu, J.; Wan, Z.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; et al. Nurses endured high risks of psychological problems under the epidemic of COVID-19 in a longitudinal study in Wuhan China. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 131, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, M.; Chahar, P. Burnout of healthcare providers during COVID-19. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2020. epub ahead of print. Available online: https://www.ccjm.org/content/ccjom/early/2020/07/01/ccjm.87a.ccc051.full.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Society of Critical Care Medicine. Clinicians Report High Stress in COVID-19 Response. 2020. Available online: https://sccm.org/blog/may-2020/sccm-covid-19-rapid-cycle-survey-2-report (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Stehman, C.R.; Testo, Z.; Gershaw, R.S.; Kellogg, A.R. Burnout, Drop Out, Suicide: Physician Loss in Emergency Medicine, Part I. West. J. Emerg. 2019, 20, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Hasan, O.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Relationship Between Clerical Burden and Characteristics of the Electronic Environment with Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medscape. Medscape US and International Physicians’ COVID-19 Experience Report: Risk, Burnout, Loneliness. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-physician-covid-experience-6013151 (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Du, M.; Hu, K. Frontline Health Care Workers’ Mental Workload During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2021, 33, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liang, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Fei, D.; Wang, L.; He, L.; Sheng, C.; Cai, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Cruz, L.N.; Cardoso, R.B.; Albuquerque, M.D.F.P.M.D.; Montarroyos, U.R.; de Souza, W.V.; Ludermir, A.B.; de Carvalho, M.R.; Vicente, J.D.D.S.; Filho, M.P.V.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of frontline healthcare workers in a highly affected region in Brazil. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.; Yuanyuan, C.; Qiuxiang, Y.; Cong, L.; Xiaofeng, L.; Yundong, Z.; Jing, C.; Peifeng, Q.; Yan, L.; Xiaojiao, X.; et al. Psychological distress surveillance and related impact analysis of hospital staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in Chongqing, China. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 103, 152198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska, K.; Majchrowicz, B.; Snarska, K.; Guzak, B. Psychosocial Burden and Quality of Life of Surveyed Nurses during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, A.G.; Olshavsky, M.E.; Newport, D.J.; Benzer, J.; Chambers, K.M.; Custer, J.; Rathouz, P.J.; Nutt, S.; Jwaied, S.; Leslie, R.; et al. Occupational Risk Factors and Mental Health Among Frontline Health Care Workers in a Large US Metropolitan Area During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022, 24, 21m03166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1859–1922. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttormson, J.L.; Calkins, K.; McAndrew, N.; Fitzgerald, J.; Losurdo, H.; Loonsfoot, D. Critical Care Nurse Burnout, Moral Distress, and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A United States Survey. Heart Lung 2022, 55, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Yun, J.; Kim, T. Stress- and Work-Related Burnout in Frontline Health-Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 17, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.; Dobnik, M. The Importance of Monitoring the Work-Life Quality during the COVID-19 Restrictions for Sustainable Management in Nursing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; McLoughlin, C.; Stillman, M.; Poplau, S.; Goelz, E.; Taylor, S.; Nankivil, N.; Brown, R.; Linzer, M.; Cappelucci, K.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 4th ed.; Mind Garden: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Linzer, M.; Poplau, S.; Babbott, S.; Collins, T.; Guzman-Corrales, L.; Menk, J.; Murphy, M.L.; Ovington, K. Worklife and Wellness in Academic General Internal Medicine: Results from a National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M. Mini Z Burnout Survey. Institute for Professional Worklife (IPS). 2015. Available online: https://www.professionalworklife.com/mini-z-survey (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.S. Factors Influencing Emergency Nurses’ Burnout During an Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Kong, Y.; Li, W.; Han, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.X.; Wan, S.W.; Liu, Z.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Clin. Med. 2020, 24, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, A.T. Teamwork in a pandemic: Insights from management research. BMJ Lead. 2020, 4, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribà-Agüir, V.; Martín-Baena, D.; Pérez-Hoyos, S. Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 80, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, D.P. User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire; National Foundation for Educational Research Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens, J.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunsaker, S.; Chen, H.-C.; Maughan, D.; Heaston, S. Factors That Influence the Development of Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Emergency Department Nurses. J. Nurs. Sch. 2015, 47, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halcomb, E.; McInnes, S.; Williams, A.; Ashley, C.; James, S.; Fernandez, R.; Stephen, C.; Calma, K. The Experiences of Primary Healthcare Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. J. Nurs. Sch. 2020, 52, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciaszek, J.; Ciulkowicz, M.; Misiak, B.; Szczesniak, D.; Luc, D.; Wieczorek, T.; Fila-Witecka, K.; Gawlowski, P.; Rymaszewska, J. Mental Health of Medical and Non-Medical Professionals during the Peak of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Nationwide Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.; Pinho, R.; Teixeira, A.; Martins, V.; Nunes, R.; Morgado, H.; Castro, L.; Serrão, C. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers during the first wave in Portugal: A cross-sectional and correlational study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas-Hernández, L.; Ariza, T.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Canadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacadura-Leite, E.; Sousa-Uva, A.; Ferreira, S.; Costa, P.L.; Passos, A.M. Working conditions and high emotional ex-haustion among hospital nurses. Rev. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 17, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.; Sloane, D.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Aungsuroch, Y. Work stress, perceived social support, self-efficacy and burnout among Chinese registered nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Fu, W.; Liu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhou, N.; Yan, S.; Lv, C. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobnik, M.; Maletič, M.; Skela-Savič, B. Work-Related stress factors in nurses at Slovenian hospitals—A cross-sectional study. Zdr. Varst. 2018, 57, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.; Treven, S.; Mumel, D. Well-Being and Satisfaction of Nurses in Slovenian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Zdr. Varst. 2020, 59, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, B.X.; et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.; Treven, S.; Mumel, D. Leadership behavior predictor of employees’ job satisfaction and psychological health. In Exploring the Influence of Personal Values and Cultures in the Workplace; Nedelko, Z., Brzozowski, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasangohar, F.; Jones, S.L.; Masud, F.N.; Vahidy, F.S.; Kash, B.A. Provider Burnout and Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned from a High-Volume Intensive Care Unit. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-King, A.; Dykes, L. Wellbeing for HCWs during COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://d29e30c9-ac68-433c-8256-f6f9c1d4a9ec.filesusr.com/ugd/bbd630_fc6de742af1442baada144de34343388.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Kenrick, D.T.; Griskevicius, V.; Neuberg, S.L.; Schaller, M. Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | At the Beginning of the Second Wave of COVID-19 | At the End of the Third Wave of COVID-19 | Z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (95% CI) Median (IQR) | n (%) | Mean ± SD (95% CI) Median (IQR) | n (%) | |||

| MBI-HSS—EE | 36.33 ± 5.95 (35.42–37.25) 37 (4) | 29.61 ± 11.3 (27.77–31.56) 28 (16) | −6.444 | <0.001 | ||

| No or mild EE (≤18) | 3 (2%) | 24 (17%) | ||||

| Moderate EE (19–26) | 11 (6%) | 34 (24%) | ||||

| High EE (≥27) | 170 (92%) | 84 (59%) | ||||

| MBI-HSS—DP | 9.36 ± 2.91 (8.9–9.8) 8 (2) | 11.54 ± 5.15 (10.72–12.42) 11 (6) | −4.240 | <0.001 | ||

| No or mild DP (≤5) | 3 (2%) | 18 (13%) | ||||

| Moderate DP (6–9) | 123 (67%) | 35 (25%) | ||||

| High DP (≥10) | 58 (31%) | 89 (62%) | ||||

| MBI-HSS—PA | 41.99 ± 9.75 (40.44–44.03) 42 (14) | 45.76 ± 4.22 (45.09–46.63) 47 (3) | −3.372 | <0.001 | ||

| High PA-< burnout (≥40) | 118 (64%) | 131 (92%) | ||||

| Moderate PA (34–39) | 33 (18%) | 7 (5%) | ||||

| Mild PA-> burnout (≤33) | 33 (18%) | 4 (3%) | ||||

| MINI Z BURNOUT SURVEY | 33.48 ± 2.15 (33.18–33.78) 33 (1) | 33.12 ± 3.23 (32.6–33.7) 33 (4) | −1.329 | 0.184 | ||

| Joyful work environment (≥20) | 184 (100%) | 142 (100%) | ||||

| WORKPLACE SATISFACTION-SUBSCALE | 11.2 ± 1.44 (11.0–11.42) 11 (2) | 12.28 ± 1.54 (12.03–12.52) 12 (2) | −7.007 | <0.001 | ||

| Highly supportive environment (≥15) | 8 (5%) | 9 (6%) | ||||

| WORKPLACE STRESS- SUBSCALE | 13.7 ± 1.42 (13.5–13.9) 14 (1) | 13.51 ± 1.9 (13.16–13.81) 13 (3) | −1.304 | 0.192 | ||

| Low-stress environment (≥15) | 31(17%) | 43 (30%) | ||||

| GHQ-12 | 16.63 ± 2.21 (16.29–16.97) 17 (2) | 13.99 ± 4.63 (13.20–14.77) 12 (06) | −7.336 | <0.001 | ||

| Variables | Emotional Exhaustion | Personal Accomplishment | Depersonalization | Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working experiences | 0.074 | 0.073 | −0.119 | 0.077 |

| Patient number | 0.246 ** | 0.113 | 0.192 ** | 0.079 |

| Concern for health | 0.250 ** | −0.017 | 0.168 * | −0.098 |

| Workload | 0.172 ** | −0.084 | 0.025 | −0.136 * |

| Concern for security | 0.206 ** | 0.183 | 0.085 | −0.098 |

| Physical activity | −0.045 | 0.124 | −0.038 | 0.160 * |

| Workplace satisfaction | −0.028 | 0.128 | −0.044 | 0.198 ** |

| Workplace stress | 0.049 | −0.007 | 0.049 | −0.092 |

| Emotional exhaustion | 1.00 | −0.032 | 0.050 | −0.058 |

| Personal accomplishment | −0.032 | 1.00 | −0.052 | 0.006 |

| Depersonalization | 0.050 | −0.052 | 1.00 | −0.040 |

| Variables | Emotional Exhaustion | Personal Accomplishment | Depersonalization | Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working experiences | −0.121 | 0.003 | −0.072 | 0.091 |

| Patient number | 0.160 | 0.058 | 0.082 | 0.039 |

| Concern for health | 0.100 | 0.024 | 0.029 | −0.054 |

| Workload | 0.181 * | −0.022 | 0.022 | −0.028 |

| Concern for security | 0.140 | −0.026 | 0.026 | −0.286 ** |

| Physical activity | −0.208 * | 0.049 | −0.130 | 0.312 ** |

| Workplace satisfaction | −0.142 * | 0.097 | −0.027 | 0.205 ** |

| Workplace stress | 0.551 ** | −0.203 ** | 0.176 * | −0.588 ** |

| Emotional exhaustion | 1.00 | −0.156 | 0.381 ** | −0.403 ** |

| Personal accomplishment | −0.156 | 1.00 | −0.193 * | 0.091 |

| Depersonalization | 0.381 ** | −0.193 * | 1.00 | −0.240 ** |

| Variables | B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 = 0.370 | Working experiences | −0.006 | 0.023 | −0.019 | −0.252 | 0.801 |

| Patients’ number | −0.623 | 1.316 | −0.041 | −0.473 | 0.637 | |

| Concern for health | −0.613 | 0.849 | −0.066 | −0.721 | 0.472 | |

| Workload | −0.617 | 0.461 | −0.115 | −1.336 | 0.184 | |

| Concern for workplace security | −0.586 | 0.357 | −0.125 | −1.917 | 0.025 | |

| Physical activity | 0.769 | 0.275 | 0.212 | 2.796 | 0.006 | |

| Workplace satisfaction | 0.324 | 0.120 | 0.212 | 2.733 | 0.007 | |

| Workplace stress | −0.044 | 0.116 | −0.028 | −0.381 | 0.703 | |

| Emotional exhaustion | −0.015 | 0.032 | −0.041 | −0.471 | 0.638 | |

| Personal accomplishment | 0.035 | 0.040 | 0.066 | 0.863 | 0.390 | |

| Depersonalization | −0.037 | 0.063 | −0.049 | −0.589 | 0.557 |

| Variables | B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 = 0.533 | Working experiences | −0.048 | 0.034 | −0.110 | −1.415 | 0.160 |

| Number of patients | −0.536 | 0.475 | −0.094 | −1.127 | 0.262 | |

| Concern for health | −0.102 | 0.350 | −0.023 | −0.292 | 0.771 | |

| Workload | −1.426 | 0.622 | −0.176 | −2.293 | 0.023 | |

| Concern for workplace security | −2.293 | 0.818 | −0.220 | −2.803 | 0.006 | |

| Physical activity | 1.067 | 0.351 | 0.242 | 3.044 | 0.003 | |

| Workplace satisfaction | 0.191 | 0.248 | 0.064 | 0.769 | 0.443 | |

| Workplace stress | −0.490 | 0.197 | −0.199 | −2.488 | 0.014 | |

| Emotional exhaustion | −0.060 | 0.130 | −0.198 | −2.080 | 0.025 | |

| Personal accomplishment | 0.210 | 0.137 | 0.125 | 1.918 | 0.044 | |

| Depersonalization | −0.097 | 0.074 | −0.109 | −1.319 | 0.190 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobnik, M.; Lorber, M. Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712766

Dobnik M, Lorber M. Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712766

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobnik, Mojca, and Mateja Lorber. 2023. "Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712766

APA StyleDobnik, M., & Lorber, M. (2023). Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study. Sustainability, 15(17), 12766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712766