The Mediating Effect of Perceived Institutional Support on Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty in Higher Education

Abstract

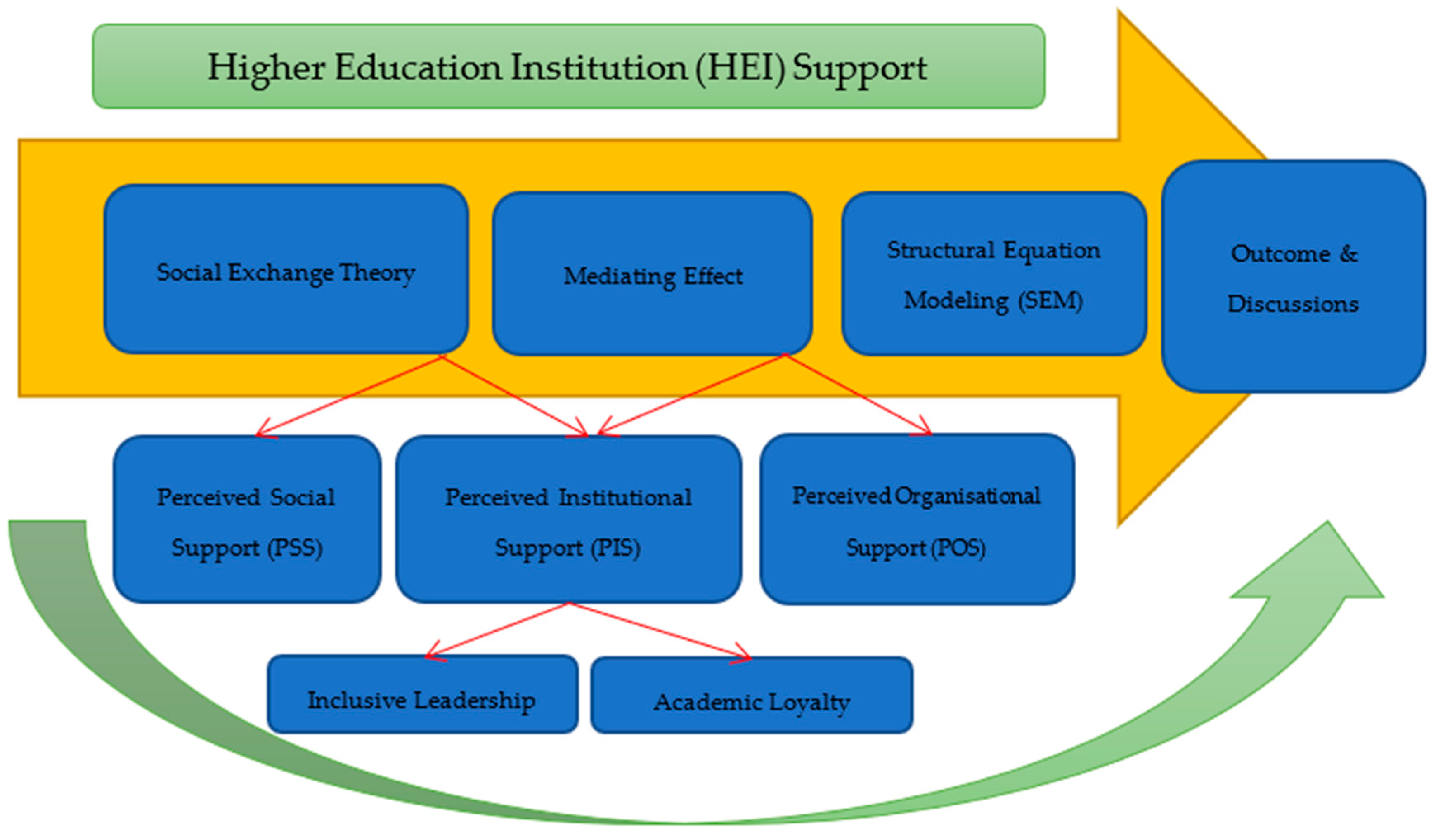

:1. Introduction

2. Theory

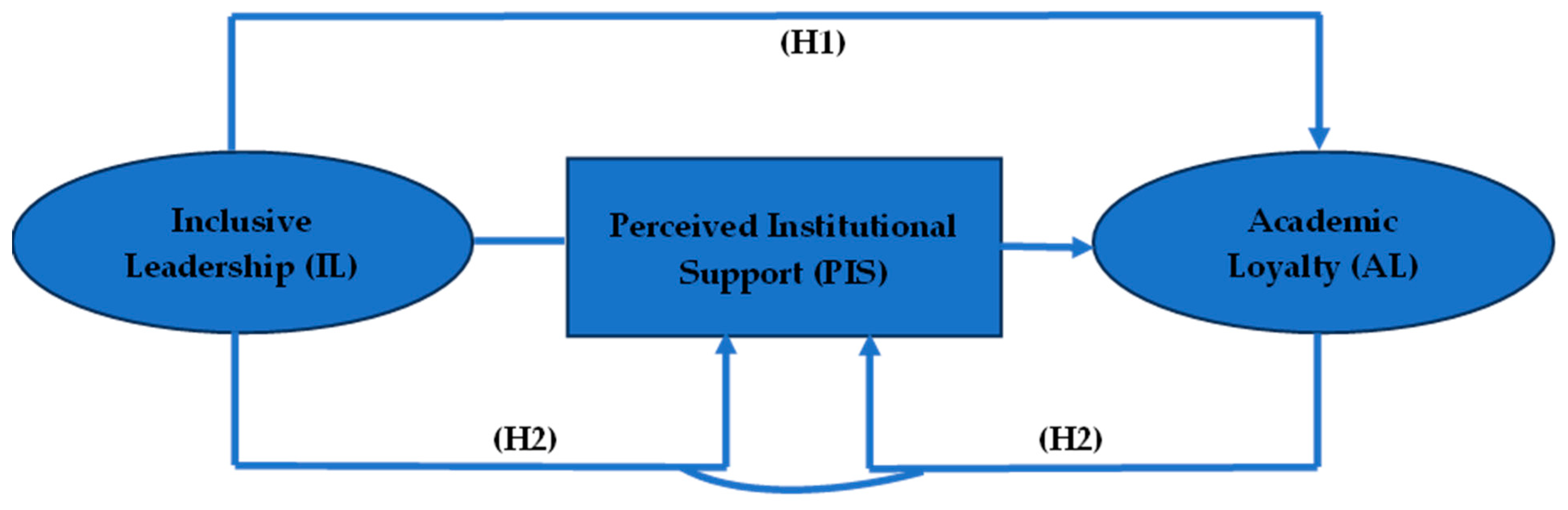

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty

2.3. Does Perceived Institutional Support Have Any Mediating Effect?

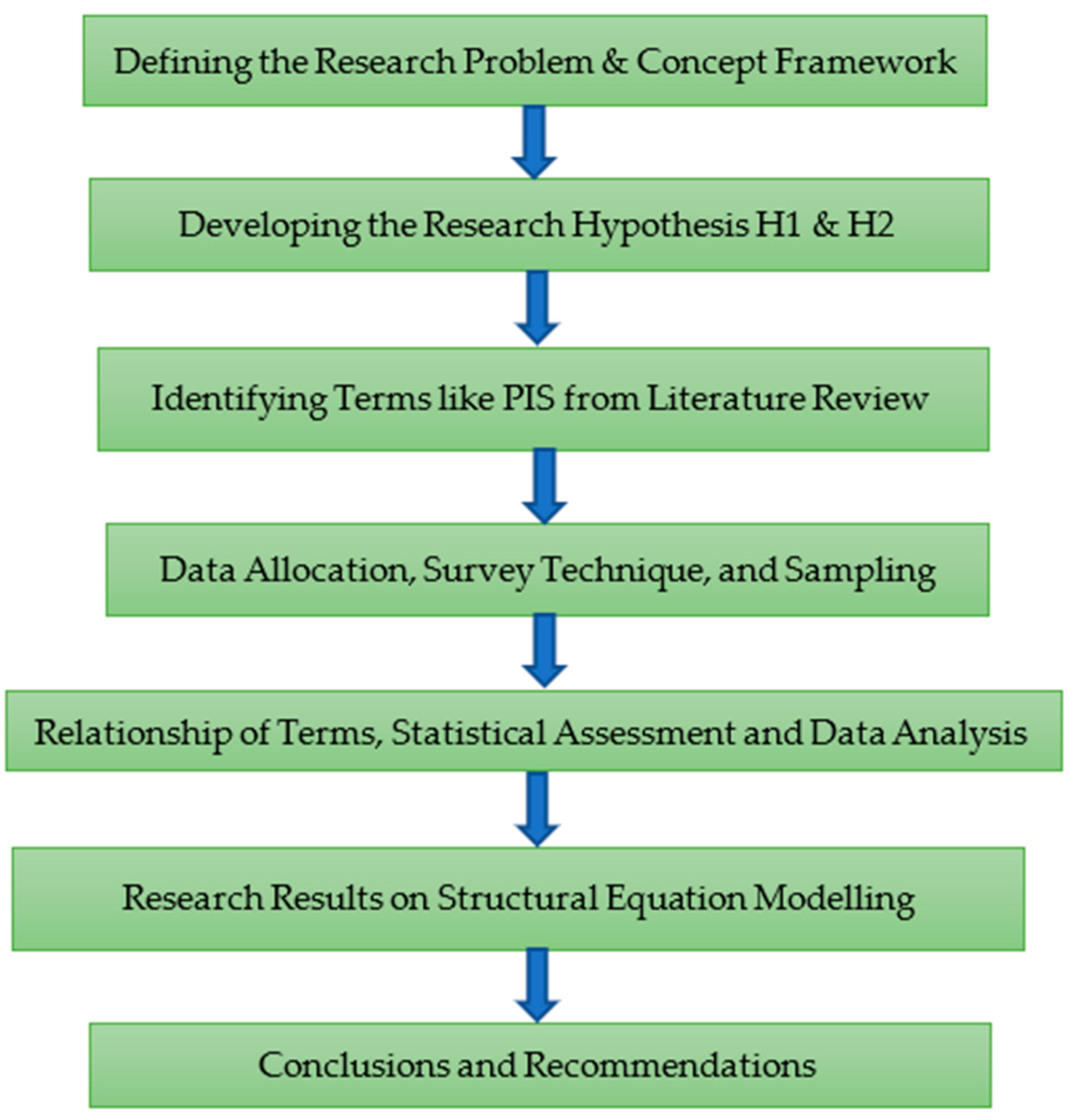

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Samples and Sampling Techniques

3.2. Likert Scale and Criteria Setting

3.3. Research Tools and Method

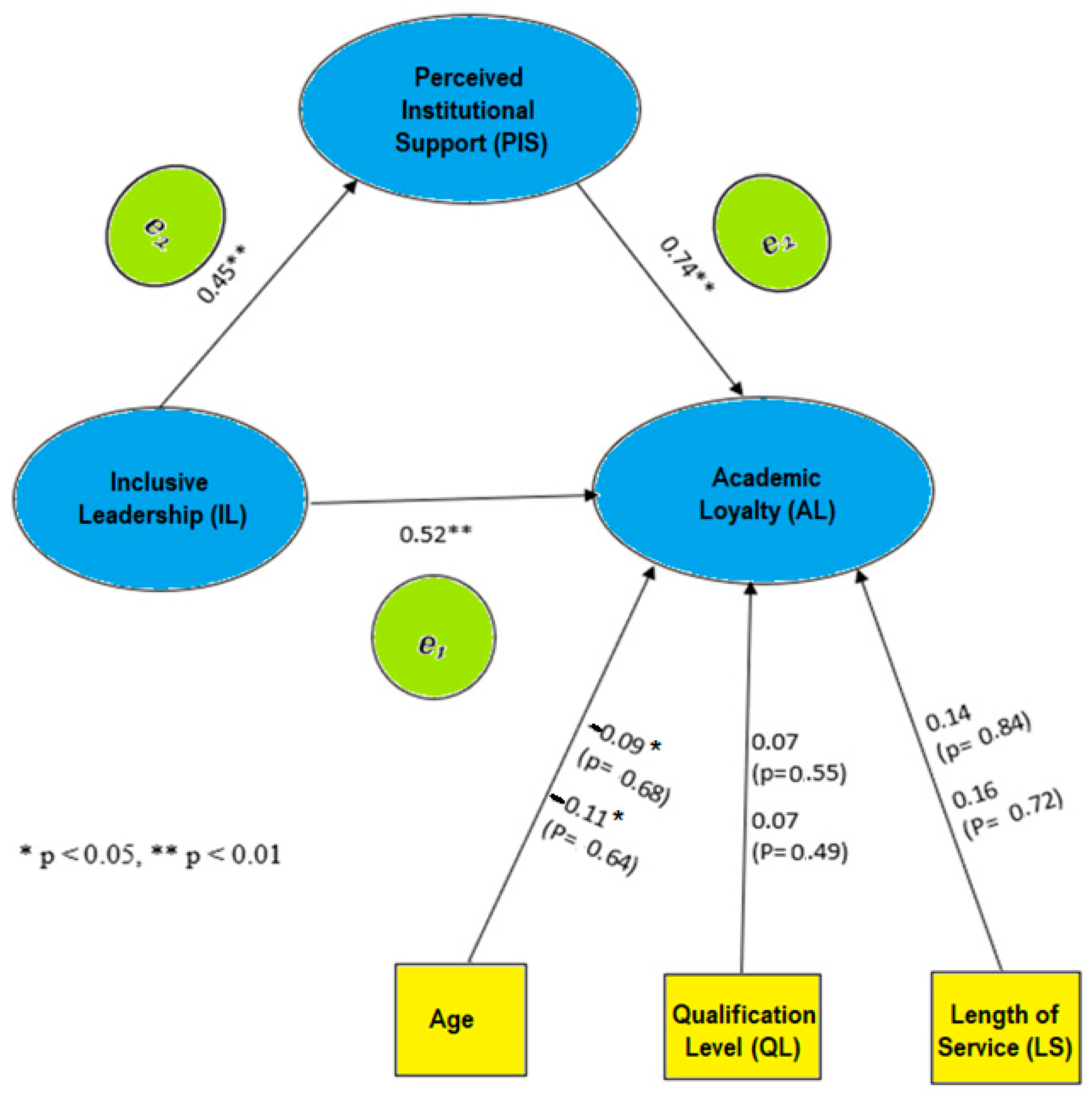

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the Sustainable Development Goals. High Educ. 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottafava, D.; Ascione, G.S.; Corazza, L.; Dhir, A. Sustainable development goals research in higher education institutions: An interdisciplinarity assessment through an entropy-based indicator. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P. An overview of the engagement of higher education institutions in the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 135694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Does online technology provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh-a comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Heras, M. What Sustainability? Higher Education Institutions’ Pathways to Reach the Agenda 2030 Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, S.; Damian, R. Higher Education for Modern Societies: Competences and Values; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2010; Volume 15, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/higher-education-for-modern-societies-competences-and-values/168075dddb (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Popov, N.; Wolhuter, C.; de Beer, L.; Hilton, G.; Ogunleye, J.; Achinewhu-Nworgu, E.; Niemczyk, E. New Challenges to Education: Lessons from around the World. BCES Conference Books, Volume 19. Bulgarian Comparative Education Society. 2021. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613922.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Chankseliani, M. International development higher education: Looking from the past, looking to the future. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2022, 48, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezar Adrianna, J.; Elizabeth, M.H. Shared Leadership in Higher Education: Important Lessons from Research and Practice; American Council on Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlehurst, R.; Goreham, H.; Woodfield, S. Why research leadership in higher education? Exploring contributions from the UK’s leadership foundation for higher education. Leadership 2009, 5, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Sustainable Education and Sustainability in Education: The Reality in the Era of Internationalisation and Commodification in Education—Is Higher Education Different? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Sustainable leadership in higher education institutions: Social innovation as a mechanism. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Eustachio, J.H.; Caldana, A.C.; Will, M.; Salvia, A.L.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Platje, J.; Kovaleva, M. Sustainability Leadership in Higher Education Institutions: An overview of challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbobaniyi, G.O.; Srivastava, S. Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty in HEIs. In Proceedings of the GBS InFER Conference, London, UK, 18 November 2022; held at Global Banking School (GBS). Institute For Educational Research (InFER), GEDU House: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chhotray, S.; Sivertsson, O.; Tell, J. The roles of leadership, vision, and empowerment in born global companies. J. Int. Entrep. 2018, 16, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prewitt, J.; Weil, R. Developing Leadership in Global and Multi-Cultural Organization. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, L. Research on the Influence of Inclusive Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behaviour. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Sports, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (SAEME 2017), Taiyuan, China, 29–30 June 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Elegido, J.M. Does it make sense to be a loyal employee? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Kalimuthu, R.; Farrukh, S.; Khan, M.S. Role of Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Employee Loyalty: Empirical Analysis from Saudi Hotel Industry. Int. J. Bus. Psychol 2020, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Neely, B.H. A structural-emergence model of diversity in teams. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Qoraboyev, I.; Gimranova, D. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. High Educ. 2021, 81, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales Franco, C.; McCowan, T. Rewiring higher education for the Sustainable Development Goals: The case of the Intercultural University of Veracruz, Mexico. High Educ. 2021, 81, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungfamai, K. State, university, and society: Higher educational development and university functions in shaping modern Thailand. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.L. Higher education in the sustainable development goals framework. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzek, E.A.; Hafen, C.A.; Allen, J.P.; Gregory, A.; Mikami, A.Y.; Pianta, R.C. How teacher emotional support motivates students: The mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learn. Instr. 2016, 42, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granziera, H.; Liem, G.A.D.; Chong, W.H.; Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J.; Bishop, M.; Tynan, L. The role of teachers’ instrumental and emotional support in students’ academic buoyancy, engagement, and academic skills: A study of high school and elementary school students in different national contexts. Learn. Instr. 2022, 80, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, V.A.N.; Frick, L.T.; Stelko-Pereira, A.C.; Zechi, J.A.M.; Amaral, E.L.; da Cunha, J.M.; Cortez, P.A. Validity evidence for the multidimensional scale of perceived social support at university and safety perception at campus questionnaire. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 107, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, K.C.P.; Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J.; Burns, E.C.; Hare, N.; Cox, S.; Flesken, A.; McCarthy, I. Academic buoyancy in high school: A cross-lagged multilevel modeling approach exploring reciprocal effects with perceived school support, motivation, and engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 1931–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Burns, E.C.; Collie, R.J.; Bostwick, K.C.P.; Flesken, A.; McCarthy, I. Growth goal setting in high school: A large-scale study of perceived instructional support, personal background attributes, and engagement outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmur, D. A critical analysis of the UNESCO/OECD guidelines for quality provision of cross-border higher education. Qual. High. Educ. 2007, 13, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, A. Quality assurance of cross-border higher education. Qual. High. Educ. 2006, 12, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaggleston, J. Research into Higher Education in England. High. Educ. Eur. 1983, 8, 66–75. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000057015 (accessed on 26 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. Inclusive Business Creation: Good Practice Compendium; Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in Ireland; OECD Skills Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in Greece; OECD Skills Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/HEInnovate%20Greece_061221.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Vikki, B.; Christopher, J. England: Tracing Good and Emerging Practices on the Right to Higher Education; Policy Initiatives on the Right to Higher Education in England. UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384293 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Meek, V.L.; Teichler, U.; Kearney, M.L. Higher Education, Research and Innovation: Changing Dynamics; International Center for Higher Education Research Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 2009; Available online: https://ds.amu.edu.et/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/12934/UNESCO%20Higher%20Education%2C%20Research%20and%20Innovation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=14 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Carlsen, A.; Holmberg, C.; Neghina, C.; Owusu-Boampong, A. Closing the Gap: Opportunities for Distance Education to Benefit Adult Learners in Higher Education; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Feldbrunnenstrasse, Germany; Hamburg, Germany, 2016. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573634.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- UNESCO. Flexible Learning Pathways in British Higher Education. UNESCO IIEP. 2021, pp. 1–14. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378004 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Brennan, J. Flexible Learning Pathways in British Higher Education: A Decentralised and Market-Based System. Report Prepared within the Framework of the IIEP-UNESCO Research Project ‘SDG 4: Planning for Flexible Learning Pathways in Higher Education’. 2021. Available online: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/about-us/flexible-learning-pathways.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Blau, P.M. A formal theory of differentiation in organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1970, 35, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselin, C. Are universities specific organizations. In Towards A Multiversity?: Universities between Global Trends and National Traditions; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2007; pp. 63–84. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/22777/1007385.pdf?sequence=1#page=64 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Davidaviciene, V.; Al Majzoub, K. The Effect of Cultural Intelligence, Conflict, and Transformational Leadership on Decision-Making Processes in Virtual Teams. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, S.K.; Gera, S.; Haque, S.N. The mediating role of organizational culture: Transformational leadership and change management in virtual teams. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2023, 28, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I.; Kim, L.E. Teacher self-efficacy, instructional quality, and student motivational beliefs: An analysis using multilevel structural equation modeling. Learn. Instr. 2020, 66, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.K. Factors influencing the learning transfer of nursing students in a non-face-to-face educational environment during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea: A cross-sectional study using structural equation modeling. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2023, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E. Inclusive Leadership: The Essential Leader-Follower Relationship; Routledge: England, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden, R.; Petrov, G.; Gosling, J. Developing Collective Leadership in Higher Education: Final Report for Research and Development Series; Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (LFHE): London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Juntrasook, A.; Nairn, K.; Bond, C.; Spronken-Smith, R. Unpacking the narrative of non-positional leadership in academia: Hero and/or victim? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 32, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. Job burnout and managerial effectiveness relationship: Moderating effects of locus of control and perceived organizational support: An empirical study on Indian managers. Asian J. Manag. Res. 2011, 2, 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Matzler, K.; Renzl, B. The relationship between interpersonal trust, employee satisfaction, and employee loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2006, 17, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, J.K.; Nussler, M.L. The managerial drivers of employee satisfaction and loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. 2000, 11, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, J.; Titus, A. Why Inclusive Leaders are Good for Organizations and how to become one. Diversity and Inclusion. Harvard Business Review. 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/03/why-inclusive-leaders-are-good-for-organizations-and-how-to-become-one (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Veli Korkmaz, A.; van Engen, M.; Schalk, R.; Bauwens, R.; Knappert, L. INCLEAD: Development of an Inclusive Leadership Measurement Tool; Tilburg University, Department of Human Resource Studies: Tilburg, The Netherland, 2022; Available online: https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/19c2fe2e-eb03-41f3-bd95-5aa12d05cf1a (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Alhmoud, A.; Rjoub, H. Total Rewards and Employee Retention in a Middle Eastern Context; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Lukman, R.; Lozano, F.J.; Huisingh, D.; Lambrechts, W. Declarations for sustainability in higher education: Becoming better leaders, through addressing the university system. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moed, H.F. A critical comparative analysis of five world university rankings. Scientometrics 2017, 110, 967–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucha, J. Country-specific determinants of world university rankings. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.J.; Grisaffe, D.B. Employee commitment to the organization and customer reactions: Mapping the linkages. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Singh, T.; Bhakar, S.S.; Sinha, B. Employee loyalty towards organization—A study of academician. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2010, 1, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, P. Leadership and employee creativity. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Zhou, J., Shalley, C.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.C.; Cheng, Y. The Academic Ranking of World Universities. High. Educ. Eur. 2005, 30, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.; Propper, C.; Smith, S. Herding cats? Management and university performance. Econ. J. 2014, 124, 534–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhvargers, A. Global University Rankings and Their Impact: Report II; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marconi, G.; Ritze, J. Determinants of international university rankings scores. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 6211–6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuknor, S.C.; Bhattacharya, S. Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Randel, A.E.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Holcombe Ehrhart, K.; Singh, G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, M.; Boal, K.; Davis, J. Institutional Leadership: Past, Present, and Future. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Suddaby, R., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 721–736. [Google Scholar]

- Otaye-Ebede, L. Employees’ perception of diversity management practices: Scale development and validation. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.A.; Farao, C. Inclusive leadership and extra-role behaviours in higher education: Does organizational learning mediate the relationship? Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 36, 397–418. [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti, J.; Bhau, S. Empirical investigation of moderating and mediating variables in between transformational leadership and related outcomes: A study of higher education sector in North India. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1123–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Ojukwu, M.C. The Effect of Inclusive Leadership and Employee Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Employees’ Voice in First Marina Trust Limited, Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arici, H.E.; Arasli, H.; Çobanoğlu, C.; Hejraty Namin, B. The effect of favoritism on job embeddedness in the hospitality industry: A mediation study of organizational justice. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behaviour: The moderating role of power distance. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Naqvi, S.M.M.R.; Khan, A.K.; Arjoon, S.; Tayyeb, H.H. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behaviour: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.C.; Mai, Q.; Tsai, S.B.; Dai, Y. An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship, and innovative behaviour from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, L.; Blessinger, P. Inclusive Leadership in Higher Education: International Perspectives and Approaches; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Inclusive education is a multi-faceted concept. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2015, 5, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmaei, A.; Sadeghinejad, Z. Inclusive leadership: A scientometric assessment of an emerging field. Adv. Ser. Manag. 2019, 22, 221–245.59. [Google Scholar]

- Aboki, F.; Pinnock, H. Promoting Inclusive Education Management in Nigeria. EENET. 2021. Available online: https://www.eenet.org.uk/enabling-education-review/enabling-education-review-4/eer-4/4-2/ (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Veidemane, A. Education for sustainable development in higher education rankings: Challenges and opportunities for developing internationally comparable indicators. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veidemane, A.; Kaiser, F.; Craciun, D. Inclusive Higher Education Access for Underrepresented Groups: It Matters, But How Can Universities Measure It? Soc. Incl. 2021, 9, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, T.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B. The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 497–519. [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Luria, G.; Brimhall, K.C. What leaders say versus what they do: Inclusive leadership, policy-practice decoupling, and the anomaly of climate for inclusion. Group Organ. Manag. 2022, 47, 840–871. [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 941–966. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, A.V.; Van Engen, M.L.; Knappert, L.; Schalk, R. About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 100894. [Google Scholar]

- Randel, A.E.; Galvin, B.M.; Shore, L.M.; Ehrhart, K.H.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Kedharnath, U. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar]

- Alfons, A.; Ateş, N.Y.; Groenen, P.J. A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2022, 25, 591–617. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, H.A.S.; Wells, B.; Guenther, S.; Matkin, G.S. The path to inclusion: A Literature Review of Attributes and Impacts of Inclusive Leaders. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2022, 21, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aselage, J.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 24, 491–509. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Morgeson, F.P. Safety-related behaviour as a social exchange: The role of perceived organizational support and leader–member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, D.A. Building a learning organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Confessore, S.J.; Kops, W.J. Self-directed learning and the learning organization: Examining the connection between the individual and the learning environment. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 1998, 9, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.E. A contextual theory of learning and the learning organization. Knowl. Process Manag. 2005, 12, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, K.; Vernoy, M.; Williams, B.; Vernoy, J. Psychology in Action; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.C.P.; Prabhakar, P.V. Personality and work motivation: A decisive assessment of Vroom’s expectancy theory of employee motivation’. Asia Pac. J. Res. 2018, 1, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. How to prevent, detect and control common method variance in electronic commerce research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed.; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Hartman, N.; Cavazotte, F. Method variance and marker variables. A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 477–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Medsker, G.J.; Williams, L.J.; Holahan, P.J. A review of current practices for evaluating causal models in organizational behavior and human resources management research. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 439–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, E.; Halle, T.; Terry-Humen, E.; Lavelle, B.; Calkins, J. Children’s school readiness in the ECLS-K: Predictions to academic, health, and social outcomes in first grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2006, 21, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. Wolman, B.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK, 19–20 June 2008; Available online: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1046&context=buschmancon (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, P.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.R.; Mulaik, S.A.; Brett, J.M. A tale of two methods. Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Smith, G.T. Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 62, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Chiu, C.M.; Chen, C.A. The effect of TQM practices on employee satisfaction and loyalty in government. Total Qual. Manag. 2010, 21, 1299–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmaz, A.; Akman, G.; Ozkan, C.; Pastuszak, Z. Empirical study of public sector employee loyalty and satisfaction. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.B.; Karim, N.B.; Patah, M.O.R.B.A.; Zahari, H.; Nair, G.K.S.; Jusoff, K. The linkage of employee satisfaction and loyalty in hotel industry in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentaro, B. Employee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Employee Loyalty: A Case of New Vision Printing and Publishing Company Limited (NYPPCL). Ph.D. Thesis, Makerere University Business School, Kampala, Uganda, 2018. Available online: https://mubsir.mubs.ac.ug/handle/20.500.12282/4634 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Onsardi, A.; Asmawi, M.; Abdullah, T. The effect of compensation, empowerment, and job satisfaction on employee loyalty. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2017, 5, 7590–7599. [Google Scholar]

- Hanaysha, J.; Tahir, P.R. Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on job satisfaction. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 219, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Sajid, S.M. A Study of Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention among Public and Private Sector Employees. J. Manag. Res. 2017, 17, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Auer Antoncic, J.; Antoncic, B. Employee satisfaction, intrapreneurship and firm growth: A model. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentareddy, S.; Suganthi, L. Building affective commitment through job characteristics, leadership and empowerment. J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavaha, C.; Lekhawichit, N.; Chienwattanasook, K.; Jermsittiparsert, K. The Moderating Effect of Effective Commitment among the Psychological Empowerment Dimensions and Organizational Performance of Thailand Pharmaceutical Industry. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 697–705. Available online: https://www.sysrevpharm.org/articles/the-moderating-effect-of-effective-commitment-among-the-psychological-empowerment-dimensions-and-organizational-performa.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Amaechi, C.V.; Amaechi, E.C.; Oyetunji, A.K.; Kgosiemang, I.M. Scientific Review and Annotated Bibliography of Teaching in Higher Education Academies on Online Learning: Adapting to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brika, S.K.M.; Chergui, K.; Algamdi, A.; Musa, A.A.; Zouaghi, R. E-Learning Research Trends in Higher Education in Light of COVID-19: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front Psychol. 2022, 12, 762819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Amaechi, E.C.; Onumonu, U.P.; Kgosiemang, I.M. Systematic Review and Annotated Bibliography on Teaching in Higher Education Academies (HEAs) via Group Learning to Adapt with COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.M. Global research activity on e-learning in health sciences education: A bibliometric analysis. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, X. Visualization analysis on the research topic and hotspot of online learning by using CiteSpace-Based on the Web of Science core collection (2004–2022). Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 1059858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, W.A.R.W.M.; Amin, I.M. A Scientometric Analysis of Twenty Years Trends in Mobile Learning, Blended Learning, Online Learning, E-Learning and Dental Education Research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2022, 11, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posillico, J.J.; Stanislav, T.A.; Edwards, D.J.; Shelbourn, M. Scholarship of teaching and learning for construction management education amidst the fourth industrial revolution: Recommendations from a scientometric analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 032022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.I.; Omotayo, T.; Ekundayo, D.; Oyetunji, A.K. Enhancing BIM competencies of built environment undergraduates students using a problem-based learning and network analysis approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A.; O’Reilly, C.A. Paradigm lost: Reinvigorating the study of organizational culture. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Valencia, J.C.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Rev. Latinoam. Psicología 2016, 48, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmbeck, G.N. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and paediatric psychology literature. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripon, C.; Gonța, I.; Bulgac, A. Nurturing Minds and Sustainability: An Exploration of Educational Interactions and Their Impact on Student Well-Being and Assessment in a Sustainable University. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, K.; Nasr, O.A.; Miladi, M.N.; Fatima, H.; Shahwar, S.; Naveed, Q.N. Potentialities and priorities for higher educational development in Saudi Arabia for the next decade: Critical reflections of the vision 2030 framework. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanu, I.A. Igwebuike as the Hermeneutic of Individuality and Communality in African Ontology. NAJOP Nasara J. Philos. 2017, 2, 162–179. Available online: https://philarchive.org/archive/IKETDO-3 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Kanu, I.A. Igwebuike as an Igbo-African philosophy of inclusive leadership. Igwebuike Afr. J. Arts Humanit. 2017, 3, 165–183. Available online: https://www.igwebuikeresearchinstitute.org/journal/3.7.10.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Dyikuk, J.J. The intersection of communication in Igwebuike and trado-rural media: A critical evaluation. J. Afr. Stud. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 2, 175–192. Available online: https://www.apas.africa/journal/J.2.3.13.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

| S/N | Themes | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leadership | [47,48] |

| 2 | Organizational Culture | [48] |

| 3 | Change Management | [48,49] |

| 4 | Teaching methods | [50] |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | KMO | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Eigen Values | Variance Expressed | α Coeff. Cronbach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive leadership (IL) | 9 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 312.17 ** | 2.42 | 62.13 | 0.77 |

| Academic loyalty (AL) | 8 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 276.39 ** | 3.22 | 71.52 | 0.76 |

| Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) | 12 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 387.41 ** | 2.71 | 57.43 | 0.84 |

| Age | 4 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 209.13 ** | 3.41 | 64.88 | 0.79 |

| Qualification level (QL) | 4 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 294.15 ** | 2.15 | 75.19 | 0.81 |

| Length of Service (LS) | 6 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 338.84 ** | 2.56 | 69.12 | 0.72 |

| Variable | Means | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | 3.670 | 0.790 | 1 | |||||

| AL | 3.130 | 0.810 | 0.410 | 1 | ||||

| PIS | 2.780 | 0.720 | 0.030 | 0.220 * | 1 | |||

| Age | 36.130 | 7.090 | −0.000 | 0.320 ** | −0.060 | 1 | ||

| QL | 3.770 | 0.880 | 0.050 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.330 | 1 | |

| LS | 8.460 | 4.610 | 0.110 ** | 0.360 | −0.000 | 0.040 | 0.220 ** | 1 |

| First Hypothesis Model (e1) | Second Hypothesis Model (e2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL → AL | 0.520 ** | IL → PIS | 0.450 ** |

| - | - | PIS → AL | 0.740 ** |

| - | - | IL → PIS → AL | 0.360 * |

| Age → AL | −0.09 (p = 0.680) | Age → AL | −0.11 (p = 0.640) |

| QL → AL | 0.07 (p = 0.550) | QL → AL | 0.07 (p = 0.490) |

| LS → AL | 0.14 (p = 0.840) | LS → AL | 0.16 (p = 0.720) |

| CMIN/df | 2.7740 | 2.7680 | |

| RMSEA | 0.0810 | 0.0810 | |

| GFI | 0.9010 | 0.8910 | |

| CFI | 0.9320 | 0.9190 | |

| NFI | 0.9110 | 0.9080 | |

| TLI | 0.9260 | 0.9230 | |

| Standardized Coefficient | T-Statistic | Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||||

| IL → AL | 0.52 | 3.43 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| IL → PIS | 0.45 | 2.86 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| PIS → AL | 0.74 | 4.35 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| Indirect effect | |||||

| IL → PIS → AL | 0.36 | 2.07 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| Total effect | |||||

| IL → AL | 0.78 | 4.63 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.01 |

| S/N | Themes | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Employee involvement | [10,123,125] |

| 2 | Job satisfaction | [54,126,127] |

| 3 | Job empowerment | [128,129] |

| 4 | Teaching methods | [130,131,132,133] |

| 5 | Learning methods | [134,135,136,137] |

| 6 | Bibliometric study on learning | [130,131,132,133,134,135,136] |

| 7 | Organizational culture | [18,48,138,139] |

| 8 | Mediating effect | [10,27,28,29,48,76,77,140] |

| 9 | Sustainable education | [12,15,24,26,86,141,142,143] |

| 10 | Sustainable leadership | [13,14,15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gbobaniyi, O.; Srivastava, S.; Oyetunji, A.K.; Amaechi, C.V.; Beddu, S.B.; Ankita, B. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Institutional Support on Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty in Higher Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713195

Gbobaniyi O, Srivastava S, Oyetunji AK, Amaechi CV, Beddu SB, Ankita B. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Institutional Support on Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713195

Chicago/Turabian StyleGbobaniyi, Olabode, Shalini Srivastava, Abiodun Kolawole Oyetunji, Chiemela Victor Amaechi, Salmia Binti Beddu, and Bajpai Ankita. 2023. "The Mediating Effect of Perceived Institutional Support on Inclusive Leadership and Academic Loyalty in Higher Education" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713195