Perceived Behavior Analysis to Boost Physical Fitness and Lifestyle Wellness for Sustainability among Gen Z Filipinos

Abstract

:1. Introduction

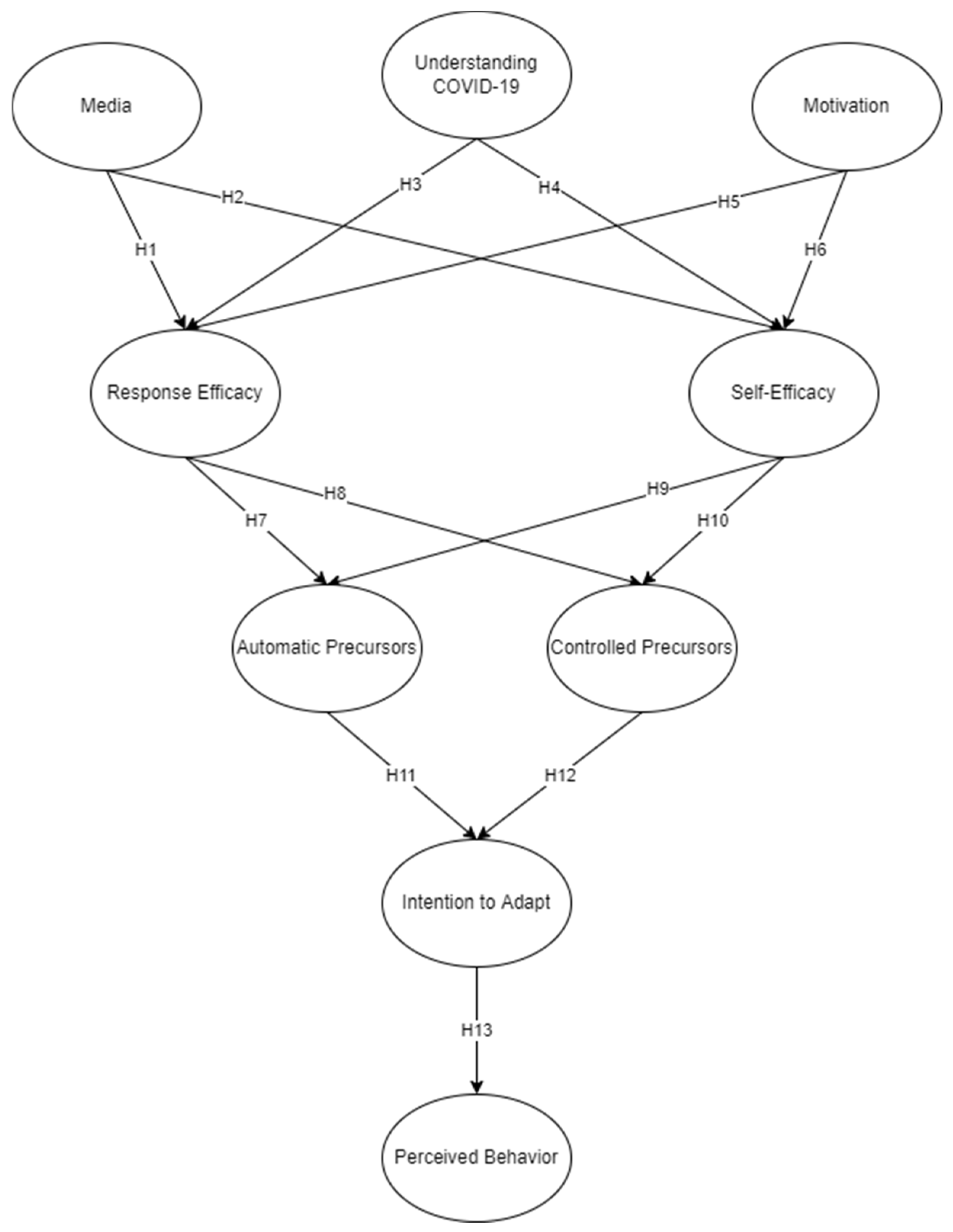

Related Studies and Theoretical Research Framework

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Questionnaire

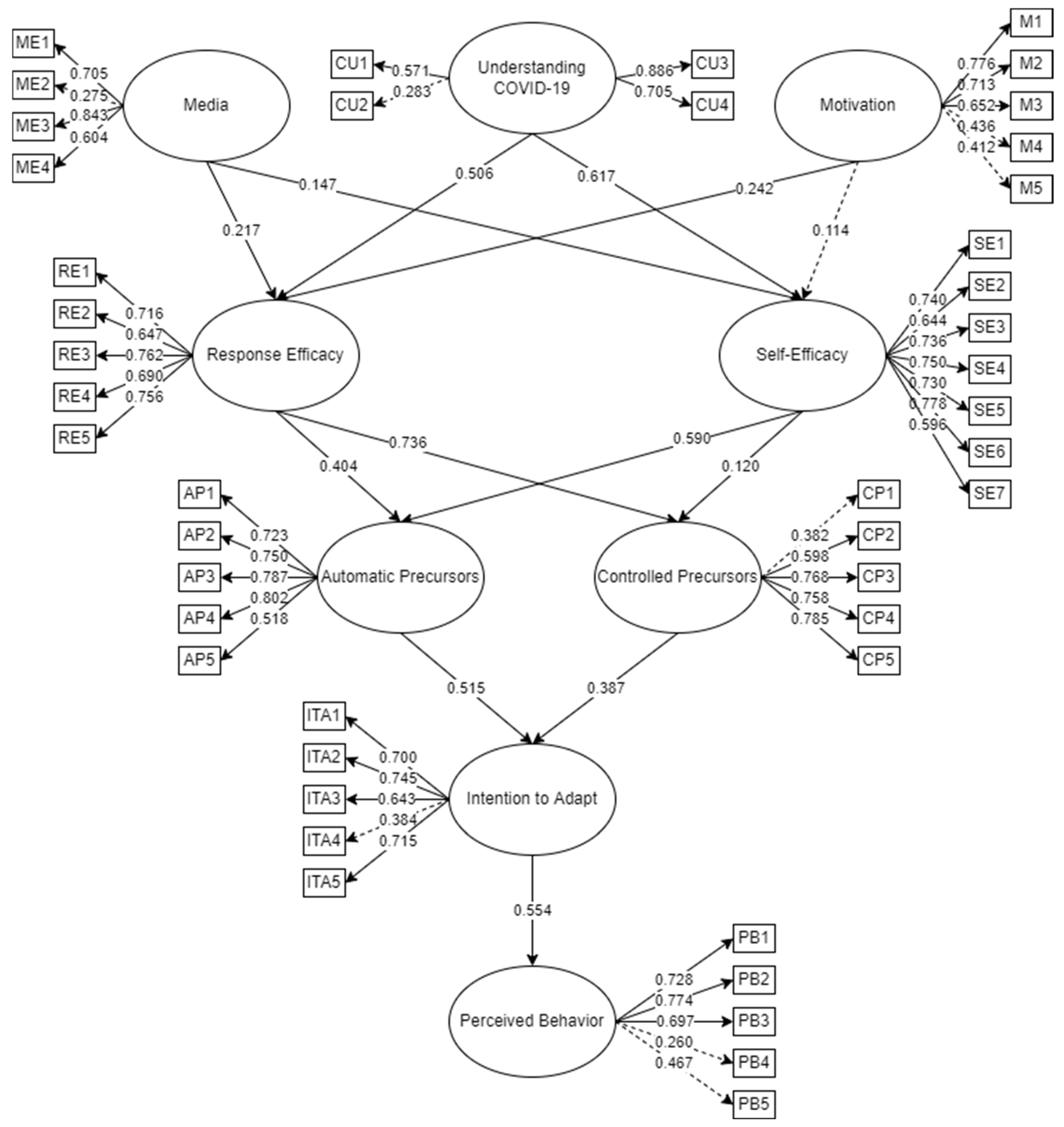

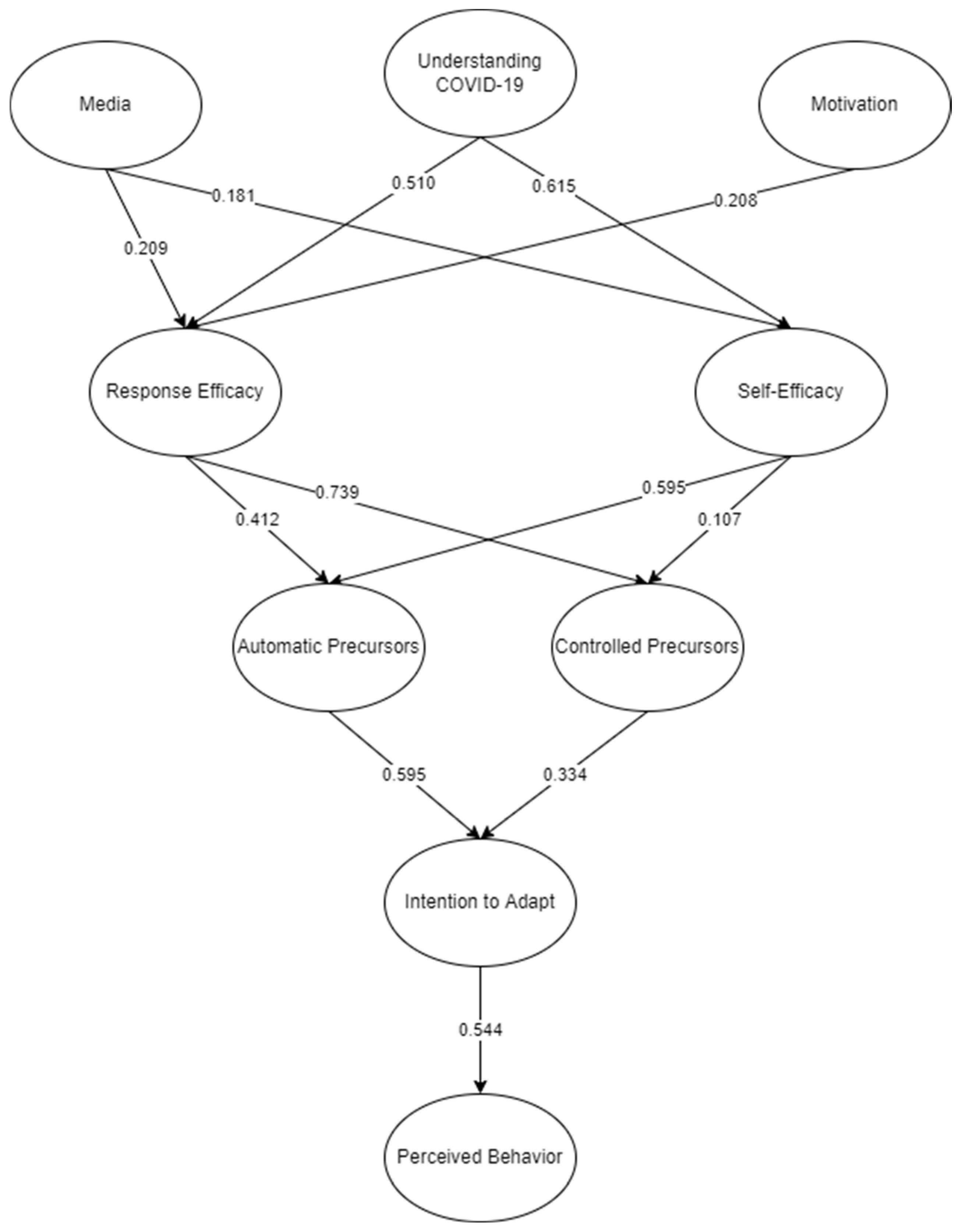

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corbin, C.B.; Le Masurier, G.C.; McConnell, K.E. Fitness for Life; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, S.; Jellum, L.; Howard, J.; Moser, A.; Mathis, D.; Collins, C.; Henderson, S.; Watjen, C. Concepts of Fitness and Wellness; Open Textbook Library: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Living: What Is a Healthy Lifestyle? Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108180 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272722 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44399 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults 65 Years and Older; Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada Physical Activity Tips for Older Adults (65 Years and Older). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/physical-activity-tips-older-adults-65-years-older.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Sedentary Behaviour Research Network Letter to the editor: Standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 540–542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, H.S.; Lopez, V. Global impact of COVID-19 on weight and weight-related behaviors in the adult population: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, A.; Severeijns, N.R.; Benson, S.; Scholey, A.; Garssen, J.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. Mood and changes in alcohol consumption in young adults during COVID-19 lockdown: A model explaining associations with perceived immune fitness and experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska, M.A.; Hamułka, J. Dietary and Lifestyle Changes During COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdowns among Polish Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey PLifeCOVID-19 Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, R. Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Olavarría, D.; Latorre-Román, P.Á.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Delgado-Floody, P. Positive and Negative Changes in Food Habits, Physical Activity Patterns, and Weight Status during COVID-19 Confinement: Associated Factors in the Chilean Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Bagon, G.M.; Dadulo, C.H.; Hortillosa, N.O.; Mercado, M.A.; Chuenyindee, T.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F. Investigating factors affecting behavioral intention among gym-goers to visit fitness centers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Integrating physical activity maintenance theory and social cognitive theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C. Health & Fitness Clubs—Statistics & Facts. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1141/health-and-fitness-clubs/ (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- IHRSA. 2019 Fitness Industry Trends Shed Light on 2020 & Beyond. 2020. Available online: https://www.ihrsa.org/improve-your-club/industry-news/2019-fitness-industry-trends-shed-light-on-2020-beyond/ (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Avourdiadou, S.; Theodorakis, N.D. The development of loyalty among novice and experienced customers of sport and fitness centres. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagir, S.; Altintig, A. The Reasons for Preference of the Fitness Centres in the Sakarya Region and the Expectations of the Individuals. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 143, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Ross, K.M.; Ranby, K.W.; Masters, K.S.; Peters, J.C.; Hill, J.O. Identifying groups at risk for 1-year membership termination from a fitness center at enrollment. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolesi, L.; Polverino, A.; Montuori, S.; Foti, F.; Ferraioli, G.; Sorrentino, P.; Sorrentino, G. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive functioning and wellbeing: Biological and psychological benefits. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, M.A.; Khabour, O.F.; Alzoubi, K.H. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Amid Confinement: The BKSQ-COVID-19 Project. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronek, J.; Boraczyński, M.; Gronek, P.; Wieliński, D.; Tarnas, J.; Marszałek, S.; Tang, Y.-Y. Exercise in aging: Be balanced. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, L.; Mullan, B.; McCaffery, K. Protection motivation theory and physical activity in the general population: A systematic literature review. Psychol. Health Med. 2013, 18, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillair, R. Protection motivation theory. Int. Encycl. Media Psychol. 2020, 3, 70–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chamroonsawasdi, K.; Chottanapund, S.; Pamungkas, R.A.; Tunyasitthisundhorn, P.; Sornpaisarn, B.; Numpaisan, O. Protection motivation theory to predict intention of healthy eating and sufficient physical activity to prevent diabetes mellitus in Thai population: A path analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, R.; Ronan, K.; Bambrick, H.; Taylor, M. Expanding protection motivation theory: Investigating an application to animal owners and emergency responders in bushfire emergencies. BMC Psychol. 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, R.E.; Mohseni, S.; Takhti, H.; Azad, M.; Shahabi, N.; Aghamolaei, T.; Norozian, F. Application of the protection motivation theory for predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan, Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 466. [Google Scholar]

- Cheval, B.; Maltagliati, S.; Fessler, L.; Farajzadeh, A.; Ben Abdallah, S.N.; Vogt, F.; Dubessy, M.; Lacour, M.; Miller, M.W.; Sander, D.; et al. Physical effort biases the perceived pleasantness of neutral faces: A virtual reality study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M.D.; Howieson, D.B.; Loring, D.W.; Fischer, J.S. Neuropsychological Assessment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cheval, B.; Boisgontier, M.P. The theory of effort minimization in physical activity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2021, 49, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, B.; Boisgontier, M.P.; Sieber, S.; Ihle, A.; Orsholits, D.; Forestier, C.; Sander, D.; Chalabaev, A. Cognitive functions and physical activity in aging when energy is lacking. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Kritz, M.; Grunseit, A.; Chau, J.; Ahmadi, M.; Holtermann, A.; Koster, A.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Johnson, N.; Sherrington, C.; et al. Barriers and enablers of vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity (VILPA) in physically inactive adults: A focus group study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruhn, J.; Schirrmacher, B. Intermedial Studies: An Introduction to Meaning across Media; Routledge: Abingdon, OX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vasuja, S.; Balamurugan, J. Imperative role of mass media to change human-health related behaviours: A review. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Crutchlow, L.; Prapavessis, H. The Short-Term Effects of Watching Consecutive Episodes of a Television Show during Treadmill Walking on Inactive Students’ Exercise Experience and Plans. 2018. Available online: http://isrctn.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Jane, M.; Hagger, M.; Foster, J.; Ho, S.; Pal, S. Social Media for Health Promotion and Weight Management: A critical debate. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Armour, K.M.; Wood, H. Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: New perspectives. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 24, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2019, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Castillo, A.M.; Salonga, L.J.; Sia, J.A.; Seneta, J.A. Factors affecting perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 prevention measures among Filipinos during enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and extended theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Güler, A. COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Meece, J.L.; Pintrich, P.R. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications; Pearson: Boston, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A.R.; Dias, R.; Neiva, H.P.; Loureiro, N.; Loureiro, V.; Marinho, D.A.; Nobari, H.; Marques, M.C. Physical activity, physical fitness, and cognitive function in adolescents. Trends Sport Sci. 2022, 29, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, C.L.; Crandall, A.; Barnes, M.D.; Novilla, M.L. Protection motivation during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of family health, media, and economic influences. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, A.; Jha, S.S.; Chakraborty, A.; Dobe, M.; Dey, A. Role of threat and coping appraisal in protection motivation for adoption of preventive behavior during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 678566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; de Bruijn, G.-J. How big is the physical activity intention-behaviour gap? A meta-analysis using the Action Control Framework. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, R.; Ekkekakis, P. Affective–reflective theory of physical inactivity and exercise. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2018, 48, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Teixeira, D.S.; Neiva, H.P.; Cid, L.; Monteiro, D. The bright and dark sides of motivation as predictors of enjoyment, intention, and exercise persistence. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Teixeira, P.; Caixeta, F.V.; Ramires da Silva, L.C.; Brasil-Neto, J.P.; Malcher-Lopes, R. Effects of CBD-enriched cannabis sativa extract on autism spectrum disorder symptoms: An observational study of 18 participants undergoing compassionate use. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raglewska, P.; Demarin, V. Dancing as non-pharmacological treatment for healthy aging in the COVID-19 era; a gerontological perspective. Trends Sport Sci. 2021, 28, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage: Andover, Hampshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ghozali, I. Multivariate Analysis Application with IBM SPSS 23 Program; Diponegoro University Publishing Agency: Semarang, Indonesia, 2016; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling: Foundations and Extensions; SAGE Publications, Incorporated: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kurata, Y.B.; Ong, A.K.; Andrada, C.J.; Manalo, M.N.; Sunga, E.J.; Uy, A.R. Factors affecting perceived effectiveness of multigenerational management leadership and metacognition among service industry companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, Y.B.; Ong, A.K.; Joyosa, J.J.; Santos, M.J. Predicting factors influencing perceived online learning experience among primary students utilizing structural equation modeling forest classifier approach. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 73, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, M.S. Structural equation modeling approaches in educational research and Practice. In Application of Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Civelek, M.E. Essentials of Structural Equation Modeling; Zea Books: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kurata, Y.B.; Ong, A.K.; Ang, R.Y.; Angeles, J.K.; Bornilla, B.D.; Fabia, J.L. Factors affecting flood disaster preparedness and mitigation in flood-prone areas in the Philippines: An integration of protection motivation theory and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Lavoie, A.; Camden, S.; Le Sage, N.; Sampalis, J.S.; Bergeron, E.; Abdous, B. Statistical validation of the glasgow coma score. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2006, 60, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N. Yapısal Eşitlik Modellemesine Giriş [Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling]; Ezgi Yayıncılık: Bursa, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; GUILFORD Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, T.; Arya, Y.K.; Mittal, S. Physical Fitness and exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative enquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi-Ani, N.A.; Anikwenze, C.; Isiani, M.C. Social Media and the COVID-19 pandemic: Observations from Nigeria. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2020, 7, 1799483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culos-Reed, N.; Wurz, A.; Dowd, J.; Capozzi, L. Moving online? how to effectively deliver Virtual Fitness. ACSM’S Health Fit. J. 2021, 25, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelienė, T.; Grønhøj, A. The role of peers, siblings and social media for children’s healthy eating socialization: A mixed methods study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Far Cardo, A.; Kraus, T.; Kaifie, A. Factors that shape people’s attitudes towards the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany—The influence of media, politics and personal characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurnaghan, S.J.; Weir, A.; Bishop, J.; Kennedy, S.; Blackbourn, L.A.; McAllister, D.A. Risks of and risk factors for COVID-19 disease in people with diabetes: A cohort study of the total population of Scotland. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyńska, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, H.; Liu, T.; Lipowski, M. Fear of COVID-19 changes the motivationfor physical activity participation:Polish-Chinese comparisons. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M.E.; Martin, B.; Matsumura, T.; Qureshi, A. Training for marathons during a marathon pandemic: Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on fitness among high-level nonelite runners. J. Sports Med. 2021, 2021, 9682520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makruf, A.; Ramdhan, D.H. Outdoor activity: Benefits and risks to recreational runners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kesmas Natl. Public Health J. 2021, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Manaf, Z.; Hadi Ruslan, A.; Mat Ludin, A.F.; Abdul Basir, S.M. Motivations, barriers and preferences to exercise among overweight and obese desk-based employees. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 19, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo-Huang, A.; Parker, N.H.; Bruera, E.; Lee, R.E.; Simpson, R.; O’Connor, D.P.; Petzel, M.Q.; Fontillas, R.C.; Schadler, K.; Xiao, L.; et al. Home-based exercise prehabilitation during preoperative treatment for pancreatic cancer is associated with improvement in physical function and quality of life. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 153473541989406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Füzéki, E.; Groneberg, D.A.; Banzer, W. Physical activity during COVID-19 induced lockdown: Recommendations. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2020, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolokoltsev, M.; Kuznetsova, L.; Romanova, E.; Shirshova, E.; Volkov, A.; Solodovnik, A.; Gnilitskaya, E. Physical activity of people who recovered from COVID-19. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 3265–3272. [Google Scholar]

- Maugeri, G.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Battaglia, G.; Pippi, R.; D’Agata, V.; Palma, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Musumeci, G. The impact of physical activity on psychological health during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallazola, V.A.; Davis, D.M.; Whelton, S.P.; Cardoso, R.; Latina, J.M.; Michos, E.D.; Sarkar, S.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Stone, N.J.; et al. A clinician’s guide to healthy eating for cardiovascular disease prevention. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baak, M.A.; Pramono, A.; Battista, F.; Beaulieu, K.; Blundell, J.E.; Busetto, L.; Carraça, E.V.; Dicker, D.; Encantado, J.; Ermolao, A.; et al. Effect of different types of regular exercise on physical fitness in adults with overweight or obesity: Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, M.P.; da Silva Fagundes, K.K.; Bizuti, M.R.; Starck, É.; Rossi, R.C.; de Resende e Silva, D.T. Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: An integrative review of the current literature. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 21, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, M.; Wright, C.J.; Carrotte, E.; Jenkinson, R.; Mulgrew, K.; Prichard, I.; Lim, M.S. “I aspire to look and feel healthy like the posts convey”: Engagement with fitness inspiration on social media and perceptions of its influence on health and Wellbeing. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perski, O.; Hébert, E.T.; Naughton, F.; Hekler, E.B.; Brown, J.; Businelle, M.S. Technology-mediated just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIS) to reduce harmful substance use: A systematic review. Addiction 2022, 117, 1220–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinska, M.M.; Davis, P.A. Recall of affective responses to exercise: Examining the influence of intensity and Time. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 573525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R.; Ulrich, L. I can see it in your face. affective valuation of exercise in more or less physically active individuals. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, W.S. Causal relationship between exercise commitment and exercise continuation intention according to the use of mobile home training: Changes in fitness after COVID-19. J. Korean Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 38, 963–973. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, W.; Friese, M.; Wiers, R.W. Impulsive versus reflective influences on health behavior: A theoretical framework and empirical review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2008, 2, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati-Najarkolaei, F.; Pakpour, A.H.; Saffari, M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Hajizadeh, F.; Chen, H.; Yekaninejad, M.S. Determinants of Lifestyle Behavior in Iranian Adults with Prediabetes: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior. Arch. Iran. Med. 2017, 20, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tapera, R.; Mbongwe, B.; Mhaka-Mutepfa, M.; Lord, A.; Phaladze, N.A.; Zetola, N.M. The theory of planned behavior as a behavior change model for tobacco control strategies among adolescents in Botswana. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Jalilolghadr, S.; Updegraff, J.A.; Broström, A.; Pakpour, A.H. Sleep hygiene behaviours in Iranian adolescents: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 27, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, K.; Yilmaz, F.; Kavalci, C.; Ozlem, M.; Demir, A.; Durdu, T.; Sonmez, B.M.; Yilmaz, M.S.; Karakilic, M.E.; Arslan, E.D.; et al. Occupational Injury Patterns of Turkey. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2013, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Birks, D.F.; Wills, P. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, N.X.; Ngoc, B.H.; Ha, N.T. The impacts of media exposure on COVID-19 preventive behaviors among Vietnamese people: Evidence using expanded protection motivation theory. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 215824402210961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Chung, W. Integrating health consciousness, self-efficacy, and habituation into the attitude-intention-behavior relationship for physical activity in college students. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 27, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Warner, L.M.; Schwarzer, R. The role of self-efficacy and friend support on adolescent vigorous physical activity. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 44, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Chen, W.; Peng, X. The influence of physical exercise on adolescent personality traits: The mediating role of peer relationship and the moderating role of parent–child relationship. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 889758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durau, J.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of User Gender. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mema, E.; Spain, E.S.; Martin, C.K.; Hill, J.O.; Sayer, R.D.; McInvale, H.D.; Evans, L.A.; Gist, N.H.; Borowsky, A.D.; Thomas, D.M. Social influences on physical activity for establishing criteria leading to exercise persistence. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Zenko, Z.; Ladwig, M.A.; Hartman, M.E. Affect as a Potential Determinant of Physical Activity and Exercise: Critical Appraisal on an Emerging Research Field; Oxford Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.; Bloxham, S. A systematic review of the effects of exercise and physical activity on non-specific chronic low back pain. Healthcare 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–40. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Hagger, M.S. Habit and physical activity: Theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda for future research. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Velez-Argumedo, C.; Gómez, M.; Mora, C. College students and eating habits: A study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Dandekar, S.P. Perceived benefits and barriers to exercise among physically active and non-active elderly people. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2019, 30, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawley-Brzoska, S.; Misra, R. Perceived benefits and barriers of a community-based diabetes prevention and management program. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimagining Journalism. Available online: https://ejc.net/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Chua, Y.T. Philippines. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021/philippines (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Social Media and Privacy: The Philippine Experience. Available online: https://fma.ph/resources/resources-gender-ict/social-media-and-privacy-the-philippine-experience/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Marar, S.D.; Al-Madaney, M.M.; Almousawi, F.H. Health information on social media. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1294–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poushter, J. Social Media Use Continues to Rise in Developing Countries but Plateaus across Developed Ones. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Farooq, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, A.K. Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritland, R.; Rodriguez, L. The influence of antiobesity media content on intention to eat healthily and exercise: A test of the ordered protection motivation theory. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 954784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finset, A.; Bosworth, H.; Butow, P.; Gulbrandsen, P.; Hulsman, R.L.; Pieterse, A.H.; Street, R.; Tschoetschel, R.; van Weert, J. Effective health communication—A key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klompstra, L.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A.; Evangelista, L.S.; van der Wal, M.H. Exercise motivation and self-efficacy vary among patients with heart failure—An explorative analysis using data from the HF-Wii Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 2353–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Li, B.; Wang, G.; Ke, Y.; Meng, S.; Li, Y.; Cui, Z.; Tong, W. Physical Fitness, exercise behaviors, and sense of self-efficacy among college students: A descriptive correlational study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 932014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.S.; Ma, Q.S.; Li, X.Y.; Guo, K.L.; Chao, L. The relationship between exercise motivation and exercise behavior in college students: The chain-mediated role of exercise climate and exercise self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1130654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, A.M.; Neace, S.M.; DeCaro, M.S.; Salmon, P.G. Trait mindfulness and intrinsic exercise motivation uniquely contribute to exercise self-efficacy. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, D.M.; Cumming, J.; Standage, M.; Duda, J.L. Images of exercising: Exploring the links between exercise imagery use, autonomous and controlled motivation to exercise, and exercise intention and behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevance, G.; Caudroit, J.; Romain, A.J.; Boiché, J. The adoption of physical activity and eating behaviors among persons with obesity and in the general population: The role of implicit attitudes within the theory of planned behavior. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 22, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 306 | 54.2 |

| Female | 259 | 45.8 | |

| Age bracket | Gen Z (18–25) | 542 | 95.9 |

| Millennials (26–41) | 14 | 2.5 | |

| Gen X (42–57) | 8 | 1.4 | |

| Boomers II (58–67) | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Occupation | Student | 517 | 91.5 |

| Part-time employee | 8 | 1.4 | |

| Full-time employee | 29 | 5.1 | |

| Self-employed | 6 | 1.1 | |

| Unemployed | 4 | 0.7 | |

| Retired | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Monthly Income Allowance | Below ₱10,957 | 464 | 82.1 |

| ₱10,957–₱21,914 | 60 | 10.6 | |

| ₱21,914–₱43,828 | 25 | 4.4 | |

| ₱43,829–₱76,668 | 11 | 1.9 | |

| ₱76,669–₱131,484 | 3 | 0.5 | |

| ₱131,485–₱219,140 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Above ₱219,140 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Geographical Residence | National Capital Region (NCR) | 276 | 48.8 |

| Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Region I—Ilocos Region | 11 | 1.9 | |

| Region II—Cagayan Valley | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Region III—Central Luzon | 93 | 16.5 | |

| Region IV-A—CALABARZON | 154 | 27.3 | |

| Region IV-B—MIMAROPA | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Region V—Bicol Region | 6 | 1.1 | |

| Region VI—Western Visayas | 4 | 0.7 | |

| Region VII—Central Visayas | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Region VIII—Eastern Visayas | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Region IX—Zamboanga Peninsula | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Region X—Northern Mindanao | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Region XI—Davao Region | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Region XII—SOCCSKSARGEN | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Region XIII—Caraga | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Do you exercise? | Sometimes | 404 | 71.5 |

| Yes | 53 | 9.38 | |

| No | 108 | 19.12 | |

| If yes, how often do you exercise? | Daily | 92 | 16.3 |

| Weekly | 221 | 39.1 | |

| Monthly | 100 | 17.7 | |

| N/A | 152 | 26.9 | |

| Do you have a nutritionist? | Yes | 9 | 1.6 |

| No | 556 | 98.4 | |

| Do you follow a specific diet? | Yes | 69 | 12.2 |

| No | 496 | 87.8 |

| Constructs | Items | Measures | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media | ME1 | I think the media influences me a lot to be physically active because of the personal experience of others. | Kaur et al. [62] |

| ME2 | I think that media, when used more carefully can cause individuals to feel less fear, panic, and confusion about contracting diseases. | Obi-Ani et al. [63] | |

| ME3 | Given the readily available online fitness programs, I think the media influences me to be more physically active. | Culos-Reed et al. [64] | |

| ME4 | I became more inclined to choose healthier food options because of media advertisements. | Ragelienė et al. [65] | |

| COVID-19 Understanding | CU1 | I think that health authorities help us prevent COVID-19 by providing safety information such as minimum health protocols, COVID-19 statistics, and vaccination updates. | El-Far Cardo et al. [66] |

| CU2 | I think COVID-19 is less fatal to individuals with comorbidity if healthy habits are incorporated into our lifestyle. | McGurnaghan et al. [67] | |

| CU3 | I exercise to be in good health and prevent COVID-19 implications. | Wilczyńska et al. [68] | |

| CU4 | Knowing the effects of COVID-19 makes me uneasy, so I engage in physical activities to improve my emotional well-being. | Wilczyńska et al. [68] | |

| Motivation | M1 | I think that I will be more motivated to exercise if I can do it in fitness and recreational centers. | Kaur et al. [62] |

| M2 | I am more encouraged to engage in physical activities when exercising with others. | ||

| M3 | I am more excited to perform outdoor exercises like walking, jogging, cycling, and other sports. | Matsumura et al. [69] | |

| M4 | The work-from-home setup motivates me to exercise and have a healthier diet. | Makruf and Ramdhan [70] | |

| M5 | Having workout equipment motivates me to be more physically active. | Abdul Manaf et al. [71] | |

| Response Efficacy | RE1 | I am encouraged to engage in exercise programs because it would improve my physical function. | Ngo-Huang et al. [72] |

| RE2 | I am encouraged to engage in exercise programs because it would improve my metabolism. | Füzéki, Groneberg, and Banzer [73] | |

| RE3 | I believe that being physically active would lessen my chances of getting sick. | Kolokoltsev et al. [74] | |

| RE4 | I believe regular physical activity has positive effects on psychological health. | Maugeri et al. [75] | |

| RE5 | I believe that eating healthy would lessen the threats of cardiovascular disease. | Pallazola et al. [76] | |

| Self-Efficacy | SE1 | I am confident in my ability to do resistance exercises (e.g., squats, lunges). | Van Baak et al. [77] |

| SE2 | I like to challenge myself to engage in aerobic physical activities. | Füzéki, Groneberg, and Banzer [73] | |

| SE3 | I like to challenge myself to engage in muscle-strengthening physical activities. | Füzéki, Groneberg, and Banzer [73] | |

| SE4 | I am confident that I can do physical exercises regularly. | da Silveira et al. [78] | |

| SE5 | It is easy for me to stick to my fitness goals. | Raggatt et al. [79] | |

| SE6 | I can control my food intake and adhere to a strict diet plan. | Raggatt et al. [79] | |

| SE7 | If I set my mind to reduce or stop drinking alcohol, smoking, and other unhealthy substances, I could immediately do so. | Perski et al. [80] | |

| Automatic Precursors | AP1 | I feel good after completing a workout routine. | Cheval and Biosgontier [31] |

| AP2 | I view the experience of physical activity to be pleasant. | Brand and Ekkekakis [47] | |

| AP3 | After completing a workout routine, I think of working out again in the following days. | Slawinska and Davis [81] | |

| AP4 | If I were asked about my feelings regarding exercising, I would say it is enjoyable. | Brand and Ulrich [82] | |

| AP5 | If I were asked about my feelings regarding exercising, I would say it is enjoyable. | Brand and Ekkekakis [47] | |

| Controlled Precursors | CP1 | I evaluate first the benefits and outcomes of physical activities before doing it. | Brand and Ekkekakis [47] |

| CP2 | I think eating nutritious foods may take a little effort but is beneficial for me. | Cheval and Boisgontier [31] | |

| CP3 | I think exerting effort to exercise is worthwhile. | Kim and Kim [83] | |

| CP4 | Regular exercise will enable me to become physically and mentally healthy. | Cheval and Boisgontier [27] | |

| CP5 | I think having a healthy lifestyle is rewarding in the long run. | Hofmann et al. [84] | |

| Intent to Adapt | ITA1 | I intend to exercise for me to be physically fit. | Kim and Kim [83] |

| ITA2 | I intend to eat nutritious food in order for me to be healthy. | Brand and Ekkekakis [47] | |

| ITA3 | I intend to avoid consuming too much junk, sweets, and other processed foods. | Rahmati-Najarkolae et al. [85] | |

| ITA4 | I intend to keep myself away from heavy alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and other unhealthy substance use. | Tapera et al. [86] | |

| ITA5 | I intend to sleep 7 to 9 h daily to boost my immune system. | Strong et al. [87] | |

| Perceived Behavior | PB1 | I believe I stayed fit during the past month. | |

| PB2 | I think I have eaten nutritious foods during the past month. | ||

| PB3 | I think I have kept myself away from consuming too much junk food, sweets, and other processed foods during the past month. | ||

| PB4 | I think I have kept myself from consuming too much alcohol, cigarette smoking, and other unhealthy substance use during the past month. | ||

| PB5 | I think I slept 7 to 9 h a day during the past month. |

| Latent Variables | Item | Mean | StDev | Variance | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | |||||

| Media | ME1 | 3.742 | 1.069 | 1.142 | 0.705 | 0.715 |

| ME2 | 4.336 | 0.806 | 0.649 | 0.275 | - | |

| ME3 | 3.731 | 1.036 | 1.073 | 0.843 | 0.836 | |

| ME4 | 3.273 | 1.156 | 1.337 | 0.604 | 0.604 | |

| COVID-19 Understanding | CU1 | 4.200 | 0.890 | 0.791 | 0.571 | 0.563 |

| CU2 | 3.795 | 1.055 | 1.114 | 0.283 | - | |

| CU3 | 3.724 | 1.084 | 1.175 | 0.886 | 0.893 | |

| CU4 | 3.627 | 1.080 | 1.167 | 0.705 | 0.703 | |

| Motivation | M1 | 4.126 | 1.060 | 1.124 | 0.776 | 0.786 |

| M2 | 3.745 | 1.244 | 1.548 | 0.713 | 0.732 | |

| M3 | 4.050 | 1.100 | 1.210 | 0.652 | 0.691 | |

| M4 | 3.207 | 1.230 | 1.512 | 0.436 | - | |

| M5 | 4.016 | 1.061 | 1.126 | 0.412 | - | |

| Response Efficacy | RE1 | 4.156 | 0.884 | 0.782 | 0.716 | 0.716 |

| RE2 | 4.096 | 0.952 | 0.906 | 0.647 | 0.647 | |

| RE3 | 4.428 | 0.768 | 0.589 | 0.762 | 0.767 | |

| RE4 | 4.607 | 0.683 | 0.466 | 0.690 | 0.696 | |

| RE5 | 4.614 | 0.658 | 0.432 | 0.756 | 0.762 | |

| Self-Efficacy | SE1 | 3.853 | 1.134 | 1.285 | 0.740 | 0.739 |

| SE2 | 3.708 | 1.100 | 1.211 | 0.644 | 0.643 | |

| SE3 | 3.919 | 1.116 | 1.245 | 0.736 | 0.735 | |

| SE4 | 3.589 | 1.197 | 1.434 | 0.750 | 0.754 | |

| SE5 | 3.002 | 1.205 | 1.452 | 0.730 | 0.735 | |

| SE6 | 3.158 | 1.148 | 1.317 | 0.778 | 0.782 | |

| SE7 | 4.165 | 1.078 | 1.163 | 0.596 | 0.597 | |

| Automatic Precursors | AP1 | 4.467 | 0.768 | 0.590 | 0.723 | 0.721 |

| AP2 | 4.262 | 0.918 | 0.843 | 0.750 | 0.748 | |

| AP3 | 3.950 | 1.067 | 1.139 | 0.787 | 0.788 | |

| AP4 | 4.085 | 0.978 | 0.957 | 0.802 | 0.802 | |

| AP5 | 3.961 | 1.140 | 1.300 | 0.518 | 0.517 | |

| Controlled Precursors | CP1 | 3.970 | 1.009 | 1.019 | 0.382 | - |

| CP2 | 4.266 | 0.836 | 0.699 | 0.598 | 0.595 | |

| CP3 | 4.446 | 0.726 | 0.528 | 0.768 | 0.764 | |

| CP4 | 4.591 | 0.653 | 0.427 | 0.758 | 0.771 | |

| CP5 | 4.657 | 0.649 | 0.421 | 0.785 | 0.798 | |

| Intent to Adapt | ITA1 | 4.352 | 0.882 | 0.778 | 0.700 | 0.729 |

| ITA2 | 4.211 | 0.899 | 0.808 | 0.745 | 0.726 | |

| ITA3 | 3.637 | 1.133 | 1.285 | 0.643 | 0.638 | |

| ITA4 | 4.349 | 0.966 | 0.933 | 0.384 | - | |

| ITA5 | 3.611 | 1.172 | 1.373 | 0.715 | 0.742 | |

| Perceived Behavior | PB1 | 3.159 | 1.263 | 1.595 | 0.728 | 0.734 |

| PB2 | 3.372 | 1.139 | 1.298 | 0.774 | 0.782 | |

| PB3 | 3.243 | 1.259 | 1.585 | 0.697 | 0.688 | |

| PB4 | 4.131 | 1.209 | 1.462 | 0.260 | - | |

| PB5 | 2.866 | 1.327 | 1.762 | 0.467 | - | |

| Goodness of Fit Measures | Parameter Estimates | Minimum Cut-off | Suggested by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.899 | >0.80 | Gefen et al. [88] |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.882 | >0.80 | Gefen et al. [88] |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.898 | >0.80 | Gefen et al. [88] |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.868 | >0.80 | Gefen et al. [88] |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | 0.836 | >0.80 | Gefen et al. [88] |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.065 | <0.07 | Civelek [89] |

| Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media | 0.756 | 0.765 | 0.525 |

| COVID-19 Understanding | 0.776 | 0.770 | 0.536 |

| Motivation | 0.625 | 0.781 | 0.544 |

| Response Efficacy | 0.824 | 0.842 | 0.517 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.858 | 0.879 | 0.511 |

| Automatic Precursors | 0.864 | 0.843 | 0.522 |

| Controlled Precursors | 0.834 | 0.824 | 0.542 |

| Intent to Adapt | 0.732 | 0.802 | 0.504 |

| Perceived Behavior | 0.781 | 0.779 | 0.541 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurata, Y.B.; Ong, A.K.S.; Cunanan, A.L.M.; Lumbres, A.G.; Palomares, K.G.M.; Vargas, C.D.A.; Badillo, A.M. Perceived Behavior Analysis to Boost Physical Fitness and Lifestyle Wellness for Sustainability among Gen Z Filipinos. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813546

Kurata YB, Ong AKS, Cunanan ALM, Lumbres AG, Palomares KGM, Vargas CDA, Badillo AM. Perceived Behavior Analysis to Boost Physical Fitness and Lifestyle Wellness for Sustainability among Gen Z Filipinos. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813546

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurata, Yoshiki B., Ardvin Kester S. Ong, Alyssa Laraine M. Cunanan, Alwin G. Lumbres, Kyle Gericho M. Palomares, Christine Denise A. Vargas, and Abiel M. Badillo. 2023. "Perceived Behavior Analysis to Boost Physical Fitness and Lifestyle Wellness for Sustainability among Gen Z Filipinos" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813546

APA StyleKurata, Y. B., Ong, A. K. S., Cunanan, A. L. M., Lumbres, A. G., Palomares, K. G. M., Vargas, C. D. A., & Badillo, A. M. (2023). Perceived Behavior Analysis to Boost Physical Fitness and Lifestyle Wellness for Sustainability among Gen Z Filipinos. Sustainability, 15(18), 13546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813546