Abstract

Coffee is one of the most highly traded commodities in global markets. However, the coffee sector experiences significant value chain asymmetries and inequalities, both at the local and global levels. While market instruments may address these imbalances, there is an increasing recognition of the need for governance models that ensure fairness throughout the coffee supply chains, from agricultural production to the roasting and consumption of coffee. This article aims to provide a state-of-the-art review and analysis of research studies on governance dynamics within the coffee chain in Colombia. Colombia is a key coffee-producing country at the global level, with relevant coffee chain governance features. The review encompasses articles published from 2008 to 2023, a period that coincides with significant political and economic transformations in Colombia. The analysis and discussion of the findings highlight key issues and insights for further research to identify potential strategies promoting equity and sustainability within Colombian coffee chain governance.

1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most highly traded commodities in global markets, with a daily consumption of approximately three billion cups. This growing global demand has fueled the expansion of coffee production and exports, with an increase of over 60 percent of production since the 1990s. Small-scale producers in tropical and subtropical countries account for more than 70 percent of coffee production, with an estimated 25 million producers directly dependent on coffee for their livelihoods [1,2]. However, despite its economic significance, the coffee sector faces numerous challenges due to the inequitable distribution of value and high price volatility. It is remarkable that only a mere 10 percent of the coffee’s estimated annual value of around USD 200 billion remains within the producing countries [3]. This disparity in value distribution significantly contributes to the sector’s difficulties. As a result, coffee-growing regions bear the burdens of persistent rural poverty and economic vulnerability. While attempts have been made to address disparities through agro-food chain strategies and agribusiness policies that prioritize the most vulnerable actors in the supply chain, the presence of severe inequalities continues to impede the socially and economically equitable development of coffee-producing countries.

The current study approaches food chain governance as the set of rules, regulations, relationships, and practices that govern the production, processing, distribution, and consumption of food from its initial production to its final consumption. It encompasses various actors, including farmers, producers, processors, distributors, retailers, consumers, and regulatory bodies. The concept of food chain governance recognizes that the food system is complex and involves interactions between multiple stakeholders across different stages.

Within this context, Colombia is a country with distinctive coffee chain governance issues that need to be addressed. First, Colombia emerges as the world’s third-largest coffee producer, following Brazil and Vietnam, and the largest producer of mild Arabica coffee at the global level [3]. Over 550,000 farmers, 95 percent of whom cultivate plots smaller than 3 hectares, sell their coffee to cooperatives. Farmers grow coffee in 22 of the 32 departments of the country and in 600 municipalities (53% of the total). The coffee sector economically sustains over 2.2 million individuals, accounting for around 26 percent of the rural population and 5 percent of the total population. Notably, the coffee industry contributes approximately 12 percent to the gross domestic agricultural product and represents more than 8 percent of the country’s total exports. These figures highlight the coffee sector’s central role in the Colombian economy and explain the strong support provided by governmental, semi-governmental, and non-governmental institutions to govern the coffee chain [4,5].

Second, the Colombian coffee supply chain is mainly based on small-scale farming. The majority of Colombian coffee farmers cultivate small plots of land, typically less than 3 hectares in size. This is in contrast to other countries, such as Brazil, where coffee production is characterized by a significant presence of larger-scale plantations, which play a prominent role [6].

Third, the Colombian coffee supply chain is widely based on the cooperative system. In Colombia, a significant portion of coffee farmers sell their coffee to cooperatives. These cooperatives play a crucial role in supporting the farmers within the coffee chain by providing technical assistance, certification services, marketing support, infrastructure development, quality control, and acting as a guarantee of purchase [7]. Fourth, recent historical events have brought about significant changes in the Colombian economic and societal structure. The peace process initiated in 2016, which marked the end of a 50-year conflict, and the recent land reform project initiated under the Petro government after decades of liberalization and land concentration processes have had profound consequences on Colombian agriculture and, subsequently, coffee chain governance.

These elements position Colombia as a valuable viewpoint for unraveling some transformative governance dynamics within the coffee supply chain. Moreover, it allows observation of the economic and political transformations taking place in Latin America and their wide-ranging impacts on regional and global agri-food supply chains. Consequently, the objective of this article is to reveal the coffee chain governance dynamics in Colombia through a comprehensive review and analysis of past research studies addressing the various economic, environmental, social, and political factors intervening in coffee chain governance.

A systematic literature review of the empirical problem of food chain governance can serve as a valuable tool for aggregating, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research to offer insights into the complexities, challenges, and opportunities of governing food supply chains. Moreover, thanks to its multidimensional perspective, this review attempts to delve into the roles played by Colombian and global actors within the coffee chain and explores the extensive ramifications of the ongoing transformations in the country for the coffee sector as a whole. Focusing on the national chains or actors within a global supply chain involves narrowing the research scope to study the specific dynamics, interactions, and implications of those actors operating within Colombia. By focusing specifically on the national chain actors within a global supply chain, the research can provide valuable insights into how local dynamics and interactions interact with the overall functioning of the larger global network. This focused analysis can be particularly useful for researchers, policymakers, and industry stakeholders interested in understanding the intricacies of a specific country’s role within the broader global supply chain.

Thus, the approach adopted by the study contributes to a nuanced understanding of the intricate interplay between the diverse factors influencing the coffee supply chain at the country and global levels. This exploration takes into account the presence of informal channels and the importance of the relationships at the local level within the coffee supply chain, acknowledging that governing these necessitates a profound understanding of the local context, which certainly deserves extensive and deep field research.

The article is structured into several sections to provide a comprehensive analysis of the issue. After this introduction, the second section outlines the chosen methodology and details the process of data collection and analysis. The third section examines the selected studies, including their geographical and temporal distribution, objectives, and covered topics. The fourth section analyzes the research findings based on the thematic categories identified in the previous section. The fifth section presents a discussion of the results, critically analyzing the emerging themes from the reviewed literature, identifying potentials, limitations, and gaps, and suggesting perspectives for future research. Finally, the sixth section offers a concise conclusion summarizing the main findings derived from the research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

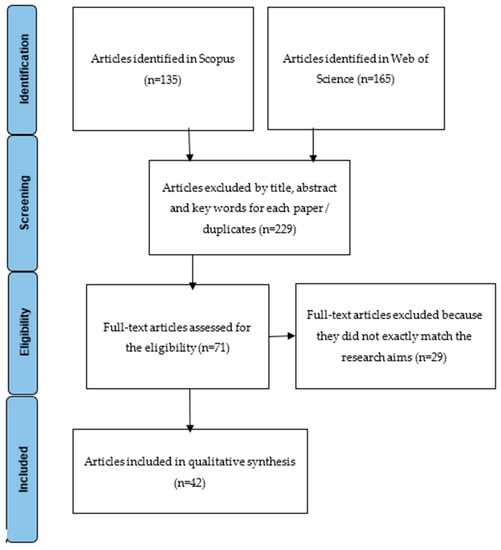

A systematic literature review provides a comprehensive and reproducible method for identifying and assessing relevant literature in a specific field. In line with the article’s objectives, this review specifically focused on studies about Colombian coffee chain governance issues. Figure 1 describes the search strategy process according to the four steps of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Collection and selection of articles.

The articles were retrieved from two scientific search engines—Scopus and Web of Science—in May 2023. Scopus and Web of Science are the most complete databases of peer-reviewed literature and can be considered warranties of peer-reviewed certified and shared knowledge. To refine the research, a search string with a specific combination of search terms was developed (Table 1). Moreover, the search was restricted to articles published between 2008 and 2023, which were considered more relevant and useful to provide a significant overview of recent coffee chain governance trends and dynamics. Before 2008, the number of publications was minimum and without continuity.

Table 1.

Search string and studied identified in Scopus and Web of Science.

The aim of the string search was to identify studies that investigate the governance dynamics of the coffee supply chain: how the stakeholders govern the chain, and what role the institutions play in supporting equitable relationships within the coffee supply chain. Thus, the search string included the key terms “coffee” and “colombia*” combined with the following terms: “governance”, “agro-food chain” and agri-food chain”, “fair*”, “certification”, “polic*”, “justice”, and “consumer*”. The search on Scopus and Web of Science yielded 135 and 165 results, respectively. During the screening phase, 65 articles were duplicates. In total, 164 articles were excluded because they were out of scope, as the papers’ title, abstract, and keywords focused on agronomic implications of environmental certifications, nutrition issues, chemical and organoleptic properties of coffee, effects on ecosystems and biodiversity considered in isolation from their chain governance implications, or briefly mentioned coffee as one among many food products. The resulting 71 articles were fully read, and 29 were eliminated as not directly relevant to the research topic. Therefore, 42 articles were included in the body of this analysis.

2.2. Data Analysis

To analyze in detail the articles, a form containing general information—author(s), title, year of publication, and journal—was created. More information was categorized, such as research objectives, country, abstract, empirical setting and methodology and sample size (where appropriate).

The research team used this form to identify the most prominent issues developed in the reviewed literature. Relevant information extracted from the reviewed studies was analyzed in detail by researchers. The researchers then agreed to group research results into homogeneous categories defining the main issues of the studies. The final grouping allowed for a better understanding and interpretation of the factors influencing governance dynamics of the coffee chain in Colombia.

The present study analyzed the articles according to the following main criteria: geographical distribution of the studies, temporal distribution of the studies, methodological approaches adopted, field of research, aims of the studies, and keywords.

3. Distribution of the Studies

3.1. Geographical and Temporal Distribution of the Studies and Publishing Journals

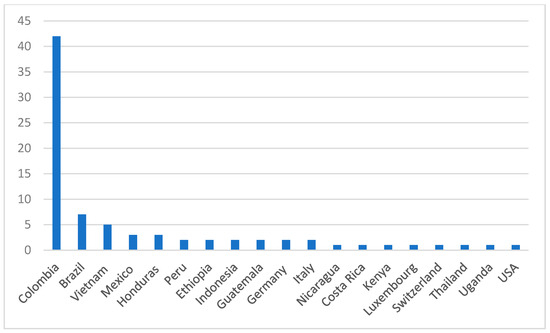

The screening phase allowed us to describe the distribution of the studies in space and time. Regarding geographical distribution, since the search string concerned a specific geographical area, the most represented country is obviously Colombia (Figure 2). However, it is interesting to note that several comparative studies also include other countries, thus underlining the existing common issues among coffee supply chain actors all around the world.

Figure 2.

Number of studies per country.

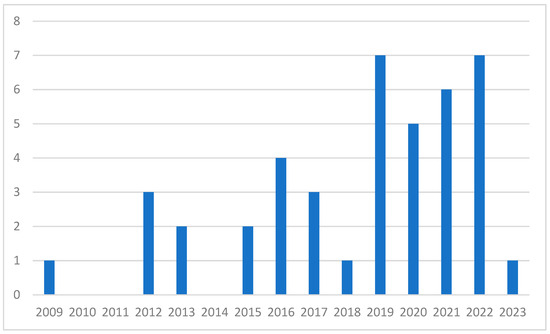

Regarding the time distribution, most studies are concentrated between 2016 and 2022 (Figure 3). The time frame of 2008–2023 was adequate for examining the recent transformations in the coffee sector. The concentration of studies in the last years shows an increasing interest on this topic and coincides with some recent significant changes in Colombia (peace process, government change, etc.) that have had an impact on the coffee chain. In this sense, the peaks in 2019, 2020, and 2022 highlight a link between these changes and some important transformations of the coffee chain in Colombia.

Figure 3.

Annual trend of studies.

The articles are well distributed among journals focused on food policies, sustainability, development studies, agriculture economics, and sociology (Table 2). Most of the journals are in English, but a significant part is in Spanish, which confirms the growing regional interest in Colombian coffee chain governance issues.

Table 2.

Publishing journals.

The research studies adopted various methodological approaches (Table 3). This summary provides a concise overview of the different methodological approaches adopted in the reviewed literature. Most of the studies adopted a mixed qualitative–quantitative approach, followed by studies based on primary and secondary data. Case study research is rather frequent.

Table 3.

Methodological approaches adopted.

3.2. Fields and Objectives of the Studies

The selected articles are from different disciplines and have different aims. Agriculture and ecological economics, development studies, and rural sociology are the most targeted fields. However, other fields, such as land management and behavioral economics, are present.

Table 4 offers a summary of the main issues of the studies. The most frequent issues of the research studies concern the effects of the certifications (Organic, Fair Trade, etc.) on the coffee producers’ income (38% of the studies). Another significant part of the studies (23.8%) is about asymmetries and inequalities along the supply chain, thus highlighting an important aspect in the coffee sector. Other aims concern issues after the ’90s liberalization process (14.3%). Lower but still significant percentages concern the role of women in the coffee sector (9.5%), the effects of the peace process on the coffee sector (7.1%), unfair practices along the supply chain (9.5%), consumer behavior regarding coffee in Colombia (7.1%), and the role of blockchains in supporting fair practices (4.8%). It is also interesting to highlight that many studies include more than one issue. This highlights how the topics and issues analyzed in the articles are interconnected. The Results and Discussion section highlights the main findings within each issue and the possible existent relations among them.

Table 4.

Issues of the studies.

The body of literature provides a broad perspective of the relevant issues related to the governance dynamics of the coffee chain in Colombia. This is highlighted by the variety of keywords (Table 5). Some keywords such as “certification/standards”, “value chain”, “Latin America”, and “women/gender” are the most common. Other common keywords are “geographical indications”, “peace/war/social conflict”, “land distribution/use”, “international trade”, “Fair Trade”, and “consumption/consumer”, thus confirming the variety of issues that need to be addressed to explain the coffee chain governance dynamics.

Table 5.

Most frequent keywords (≥3 articles).

4. Results

To provide a systematic examination of the prevalent themes identified in the reviewed studies, the study results merge into the developed distinct sections, and sub-sections when appropriate. Each of these sections corresponds to a specific main issue identified in the studies. Supplementary Material provides the detailed analysis of each study reporting key information of the reviewed studies, including the main issues addressed (Supplementary Material).

4.1. Role of Certifications and Agro-Food Chain Relationships

4.1.1. Certifications, Geographical Indications, and Origin Labels

Certifications and origin labels are some of the tools adopted in the coffee sector since the ’70s and mostly after the ’90s liberalization of the coffee market. The most famous and established certifications are Fair Trade, Organic, Geographical Indication (GI), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), Protected Denomination of Origin (PDO), and Denomination of Origin (DO).

Many studies of our selection are focused on establishing the effectiveness of these tools in ensuring sustainability from an ecological, social, and economic point of view [4,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The results are contradictory. While some authors highlight the benefits of certification for all market players, most of them reveal that certification does not have a significant role in ensuring a greater income for weaker actors, such as farmers, in the supply chain.

Among the authors who consider certification to be a positive factor, Rueda and Lambin [4] argue that certification is an important tool for ensuring environmental sustainability and improving the income of farmers, allowing them to access new chains in which more value is generated. In their opinion, this is even more important in a global scenario in which trade liberalization has increased smallholders’ exposure to market volatility and economic shocks. They also highlight the role of the FNC in supporting economically and technically the smallholders, which allows less burdensome costs for obtaining the certifications.

This role of FNC has also been highlighted by Vellema et al. [11]. Agricultural extension and income support are part of the programs of the Colombian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. These authors mention a dedicated program, called Protección del Ingreso Cafetero (PIC), to help producers take the steps required to have their coffee qualified as specialty in order to get price premiums.

Hernández-Aguilera et al. [14] highlight the effectiveness of Fair Trade in promoting alternative business models based on trust and quality. In their opinion, Fair Trade empowers smallholders to organize into cooperatives, which allows them to compete better on a global scale. Although, as they admit, these certifications imply additional costs for the growers, and a regulatory framework is needed in order to support the weaker actors along the supply chain, they offer opportunities for small farmers. In this sense, the role of cooperatives is crucial in linking smallholders with high-value markets. Establishing an adequate and fair payment scheme for farmers is essential, since the allocation of price premiums remains a major challenge in specialty coffee business models.

Giuliani et al. [13], through an econometric analysis based on data from a cross-country survey covering 575 farms in various regions of Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Mexico, highlight the positive effects of Organic and Fair Trade certifications, especially in terms of farmers’ environmental conduct, and soil management techniques. However, these authors emphasize that certifications alone have little impact in terms of economic improvement and social conduct and are more effective in the presence of an institutional framework that hinders unfair practices and favors education and access to credit. Moreover, regarding food security, they report that certified small farmers have more difficulties than non-certified farmers due to the specialization in coffee at the expense of other crops.

Other scholars are more critical about the role and effectiveness of certifications. Through a survey of 600 growers, Dietz et al. [7] highlight that, although Fair Trade can improve the income of farmers by establishing a minimum floor price (1.40 USD/lb for green Arabica coffee) and a fixed social premium (0.20 USD/lb), in most cooperatives only part of the harvest is sold under Fair Trade contracts.

Other studies support these findings. In their study of Colombian coffee producers Quiñones-Ruiz et al. [10] argue that certifications are strategies from the Global North that do not take into account all the asymmetries along the international supply chains and might shift, albeit unintentionally, power relations in favor of global corporations. However, they also recognize that in the specific case of Colombia—a developing country with a relevant self-organization of coffee producers and a solid multi-level and multi-actor governance framework—GIs have an important impact on the growers’ income. According to these authors, certifications and origin labels have a more positive impact where the producers are well organized. Self-organization and robust and context-sensitive policies are pre-conditions of the certifications’ and labels’ effectiveness [10].

Ibanez and Blackman [12] dispute that eco-certification and other certifications are a win-win solution. While the changes caused by certification have a positive impact on the environmental outcomes, it is more difficult to establish a positive effect on the farmers’ income. According to these scholars, certifications seem to benefit intermediaries and retailers more than producers. Among Colombian growers, medium and wealthy farmers benefit more than small and low-income farmers due to the high costs and strict requirements of the certifications and sustainability standards. Similar results and considerations have been reported by Beuchelt [9], Gómez-Cardona [8], Rámirez-Gómez [16], and Valbuena et al. [15]. In their studies, these authors highlight how certification costs and requirements can be burdensome for smallholders. To avoid this risk, specific policies aimed at supporting the growers with specific funds, training, access to land, and credit are needed.

4.1.2. Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Specialty Coffee

Besides certifications, over the last decades, other private tools called voluntary sustainability standards (VSSs) have emerged with the aim of certifying sustainable production. These additional standards require products to meet specific economic, social, and environmental sustainability metrics and are mostly designed and marketed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or private firms. Some examples are C.A.F.E. Practices, Nespresso AAA, and 4C. Another additional tool for certifying the quality of coffee is the designation of Specialty Coffee, created by the Specialty Coffee Association, which is assigned to any coffee that has achieved a score of 80 or higher out of 100 on a standardized score sheet by a panel of expert coffee tasters known as Q Graders [14].

The effectiveness of these tools has been the subject of focus for several scholars. Hernández-Aguilera et al. [14] emphasize the significance of quality labels such as Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices and Nespresso’s AAA Sustainable Quality Program. While acknowledging that specialty markets involve additional costs for growers, the authors argue that these markets present opportunities for small farmers. However, they also emphasize the importance of a supportive regulatory framework to ensure that weaker actors in the supply chain receive adequate support. This highlights the need to strike a balance between the potential benefits of specialty markets and the need to address the challenges faced by small farmers through appropriate regulations and support mechanisms.

Several scholars have focused on the effectiveness of these tools. Hernández-Aguilera et al. [14] support the importance of quality labels, such as Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. and Nespresso’s AAA. Although, as they admit, specialty markets imply additional costs for the growers and a regulatory framework is needed in order to support the weaker actors along the supply chain, these markets offer opportunities for small farmers.

Baquero-Melo [19] analyzes the strategies utilized by several stakeholders in Colombia, highlighting that multinational roasting companies and retailers capture much of the value along the supply chain. Big corporations monopolize the supply of specialty coffee, while products with fair trade and organic certification benefit a small percentage of farmers able to take advantage of niche markets without changing the global trade distribution.

Dietz et al. [7] highlight that VSSs seem to have little or even a negative impact on the growers’ income due to their costs. According to these authors, marketing strategies, support programs, and an adequate regulatory framework seem to have a far more significant economic impact on smallholders, regardless of whether the growers hold additional certification.

Miatton and Amado [20] argue that a regulatory framework that prioritizes transparency and fairness in the coffee supply chain is more effective in improving the income of smallholder farmers compared to relying solely on certifications and VSSs. The authors contend that certifications and specialty coffee labels can pose challenges and burdens for small farmers, which is particularly relevant in the Colombian coffee sector, where the majority of growers are smallholders.

Based on this review, there is a lively debate among scholars regarding the effectiveness of certifications, origin labels, and VSSs in the Colombian context. The findings present a mixed picture, although a critical trend seems to emerge. In summary, these tools, which have gained popularity since the liberalization process in the 1990s, show positive results in terms of environmental sustainability. However, their impact on providing economic opportunities for smallholders and growers is less positive. Consequently, the role of institutions and cooperatives becomes crucial to ensure that certification costs are not overly burdensome for smallholders and that price premiums are distributed fairly among farmers.

4.2. Fairness along Coffee Agro-Food Chain

4.2.1. Asymmetries, Inequalities, and Unfair Trade Practices

Due to a significant increase of over 60% since the 1990s, the coffee sector has experienced substantial growth in recent decades, creating economic opportunities in numerous countries, including Colombia. However, this growth has not been accompanied by an equitable distribution of value throughout the supply chain, resulting in persistent barriers, asymmetries, and inequalities. This issue has been consistently reported in various studies on the coffee industry [10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

The coffee value chain is notably intricate and opaque and involves multiple stakeholders. In the upstream value chain, various actors can be identified, ranging from input suppliers to roasters. Smallholder farmers in developing countries, particularly Colombia, produce coffee beans, primarily Arabica (though Robusta beans are also produced). The majority of coffee is exported in its raw or “green” form and is delivered to roaster companies, typically located in developed countries. Although the distribution of value along the supply chain varies across contexts, it is generally acknowledged that roasters and retailers capture a significant portion of the value, while coffee-producing countries, especially smallholder farmers, receive only a minimal percentage of the final price paid by consumers [20]. This reality holds true even in the case of Colombia, despite the presence of well-organized coffee producers, predominantly smallholders, represented by cooperatives and federated under a robust association such as the National Federation of Coffee Producers (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, FNC).

Numerous studies focusing on this topic highlight these concerns. In a recent study conducted by Moreira and Lee [24] employing a global value chain (GVC) analysis encompassing the three largest producers and exporters of unprocessed coffee in the world—Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia—a scenario emerges wherein processors, roasters, and retailers, predominantly Swiss, German, US, and Italian corporations, leverage their considerable market power to appropriate a significant share of the value along the global chain. Some roasters exhibit higher shares of value compared to their shares in volume, underscoring their dominant position in segments with high value added. In many instances, they also exert control over different links in the chain, along with the commercialization of their products, by establishing internal retail networks or entering into exclusive distribution agreements with supermarket chains. Consequently, corporations headquartered in developed countries amass the largest trade surplus. Switzerland, Italy, and Germany collectively account for 95.1% of the global roasted coffee trade surplus. Lerner et al. [23] conducted an analysis of the distribution of value within the supply chain, with a specific focus on the factors driving the disparity between prices paid to farmers and those paid free-on-board (FOB). According to their research, this difference stems from various issues. The first issue pertains to an imbalance of power among growers, negotiators, and buyers (distribution, processing firms, and retail) resulting from unfair trading practices (UTPs). These UTPs arise from three factors that negatively impact the weaker party: (1) limited alternatives for trading, (2) technological dependence, and (3) informational asymmetry, characterized by incomplete or unclear contracts that enable opportunistic behavior during contract execution.

Miatton and Amado [20] corroborate the opaqueness and imbalance of the coffee value chain in their analysis. Remarkably, producing countries retain less than 10% of the total value (approximately USD 200 billion annually). Producers face challenges, such as low and volatile prices for green coffee and limited market access. They receive meager compensation and frequently rely on government aid, which is also true for Colombia. The authors employ a specific index, namely the Commodity Fairness Index (CFI), to quantitatively calculate and measure the inequality present along the value chain [20]. The data used to construct this index unveil a stark reality: producers capture a mere 5% of the total value despite constituting 89% of the chain’s population. Exporters (1% of the chain’s population) capture 9% of the value, while importers and roasters (1% and 3% of the chain’s population, respectively) capture 32% and 45% of the value, respectively. According to these authors, blockchain technology, more so than certifications and VSSs, has the potential to alleviate this imbalance.

4.2.2. Role of Institutions and Importance of Farmers’ Self-Organization

The challenge of addressing inequalities and asymmetries within the coffee chain has been extensively analyzed by numerous authors. Within the strategies proposed by these studies, two key elements emerge as predominant: the role of institutions in establishing a robust legal framework that promotes greater equity throughout the supply chain, and the importance of coffee growers’ ability to self-organize and cooperate, thereby empowering themselves in the face of more dominant industry players. These elements highlight the need for a multifaceted approach that combines institutional support with grassroots initiatives to foster a more inclusive and fair coffee industry.

Moreira and Lee [24] attribute the unequal dynamics of the coffee chain to structural and artificial barriers associated with monopolistic marketing channels, protectionist policies implemented by European and US countries, and difficulties faced by coffee-producing nations in accessing the technologies employed in coffee processing. Overcoming such barriers and implementing appropriate countermeasures is crucial for achieving a more equitable distribution of value. The authors propose the formation of a coffee cartel, akin to OPEC, as a radical option to unite major coffee-producing countries and enhance their influence in the global market [24].

Lerner et al. [23] highlight how the inequalities are also related to domestic asymmetric price transmission and other inefficiencies in the coffee chain, stemming from information and bargaining power asymmetries. To address this imbalance and foster fairer exchanges, the authors suggest enhancing and optimizing the institutional environment [23]. The key lies in implementing appropriate policies to reduce the number of intermediaries and transaction costs. Moreover, it is crucial to enhance public infrastructure by investing in logistics, technology, and education, which would lower transportation costs and minimize information asymmetries. In this regard, robust institutions and farmers’ organizations play an indispensable role in ensuring efficiency, fairness, and equal opportunities.

Some scholars emphasize the necessity of a regulatory framework to mitigate inequalities and asymmetries within the Colombian coffee chain [22,23,24,26]. In this context, the pursuit of distributive justice should strive for systemic change at both the local and global levels. Geographical indications (GIs), as proposed by Quiñones-Ruiz et al. [10], can assist in protecting local producers, but their effectiveness relies on coffee growers attaining power through self-organization and collective action.

Other scholars highlight the significance of self-organization, collective action, and institutional efforts to establish new power balances and promote equitable value distribution [15]. Rueda and Lambin [4], Albertus [21], and Baquero-Melo [19] introduce land distribution as an additional element for analyzing the coffee sector. Albertus [21] argues that the expansion of the global coffee market has intensified pressure on public lands and small-scale farmers, resulting in the allocation of public lands to private farmers and land concentration in Colombia. Baquero-Melo [19] highlights the significant disparities in land ownership within the coffee industry. His study reveals that merely 1% of large-scale farms, consisting of approximately 6000 farms, account for a substantial 15% of the total coffee-planted area. Remarkably, this proportion is nearly equivalent to the land area (16%) cultivated by the lower 50%, comprising around 274,000 small-scale farmers [19]. Implementing policies that facilitate the redistribution of land has the potential to play a significant role in addressing and rebalancing inequalities within the coffee sector. Land redistribution can contribute to creating a more equitable distribution of resources, enabling small-scale coffee producers to have access to land and resources that were previously concentrated in the hands of a few. By providing opportunities for smallholders and marginalized communities to access productive land, these policies can foster greater economic empowerment and reduce disparities in the sector.

These considerations collectively indicate that these disparities along the coffee chain in Colombia stem from both external and internal factors, driven by power imbalances at local and global scales, which predominantly impact producers, particularly small farmers. Most authors advocate for systemic change rather than relying solely on market tools such as certifications or VSSs. The self-organization of farmers and institutional support are indispensable in achieving this transformation. By addressing these aspects, it becomes possible to create an environment where all actors in the coffee chain can thrive and contribute to a more sustainable and equitable future for the industry.

4.2.3. Role of Blockchains in Supporting Fairness along the Coffee Chain

In recent years, blockchain technology has gained prominence and momentum as a tool for ensuring traceability, equity, and fairness along supply chains. Essentially, a blockchain is a decentralized, distributed, and public digital ledger used to record transactions across multiple computers. This characteristic endows blockchains with tremendous potential to enhance traceability and performance by providing security and transparency. However, the benefits and challenges of this technology in agro-food systems have not yet been thoroughly analyzed. There is a lively discussion concerning the development methods of blockchains, standardization issues, technical integration, accessibility, participant collaboration, and trust [20,27,28,29].

In this review of the coffee sector in Colombia, two articles discuss the potential role of blockchains in reducing asymmetries and inequalities in the coffee chain. The expectations and proposals regarding this technology differ. Miatton and Amado [20] hold an optimistic viewpoint. According to these authors, the initial step towards improving fairness and balance in the coffee industry involves bringing transparency to an opaque value chain. They describe the architecture of a web app built on a blockchain framework, which is based on the following principles: (a) delivering full transparency, (b) enabling collaborative demand management between farmers and buyers, (c) ensuring end-to-end traceability and verified provenance throughout the entire supply chain, (d) enabling farmers’ visibility and promoting inclusive business models, (e) allowing producers to securely share audits and certificates, and (f) ensuring data confidentiality. The authors argue that implementing such an app could create a more transparent environment in which inefficiencies, asymmetries, and inequalities are readily identified. Clear identification of these issues could lead to their reduction or resolution.

On the other hand, Singh et al. [29] adopt a more critical stance. In an empirical study on coffee producers in Colombia, they argue that claims regarding the transparency and sustainability benefits of blockchain technology remain largely theoretical. They highlight the lack of understanding regarding how the current imbalances can affect the design and implementation of blockchain projects. Given the existing asymmetries, there is a risk that blockchain technology might exacerbate power imbalances, favoring the most influential actors and enabling larger companies to protect their brand image cost-effectively. Moreover, as suggested by these authors, in the absence of redistributive measures, the costs and risks associated with blockchain implementation and use would disproportionately burden small producers upstream rather than larger actors downstream in the supply chain [29]. This highlights the paradoxical risk of potentially intensifying income inequality instead of mitigating current asymmetries.

From these studies, it can thus be inferred that blockchain technology can effectively contribute to improving equity and fairness in the coffee sector, but only if accompanied by a regulatory framework that deals with the existing asymmetries and supports weaker actors throughout the supply chain. From this perspective, it becomes quite clear that establishing this framework and extending support, including educational and financial assistance, to small and medium producers can create the most conducive environment for the successful and effective integration of blockchain technology.

4.3. Coffee Agro-Food Chain Development

As mentioned in the introduction, two significant events have played a crucial role in shaping Colombia’s recent history: the liberalization of the coffee market following the dismantling of the quota and price regulations of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989, and the peace process initiated in 2016 between guerrilla forces, the Colombian state, and paramilitary groups. These events have had significant political and economic implications for the development of the coffee agro-food chain, as discussed extensively by scholars [8,18,26,30,31,32,33,34].

4.3.1. Coffee Sector and the Liberalization Process

The failure to reach an agreement on new export quotas in 1989 had far-reaching effects worldwide. In Colombia, as several scholars have emphasized, the main consequences were increased exposure to an unregulated global market and, subsequently, price volatility and speculation and increased investment costs, primarily impacting small producers and rural communities. Producers bore the brunt of these effects, while many businesses involved in shipping, banking, and commerce within the National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC) also suffered and declared bankruptcy [30]. Although there is no consensus among scholars regarding the exact consequences of this change, all the articles analyzed here concur that the dissolution of the ICA had predominantly negative effects on the actors within coffee-producing countries, including Colombia.

Utrilla-Catalan et al. [26] conducted an analysis of the dynamics and evolution of the international green coffee market between 1995 and 2018. They highlighted the increasing power imbalance in the global coffee trade during this period, with fewer countries playing a significant role. The collapse of the ICA resulted in a shift in control of the international coffee trade from producing to processing and consuming countries. Consequently, this led to greater inequality between producing and importing countries, creating an increasingly buyer-, trader-, or roaster-driven value chain. Additionally, speculative processes contributed to a “coffee paradox” characterized by lower and unstable prices for producers and higher prices for consumers. The decrease in farmers’ income also prompted young people to abandon agricultural land, leading to mass migrations and the rapid urbanization process observed in Colombia and other coffee-producing countries [26].

Baquero-Melo [19] argues that the liberalization process exerted greater pressure on Colombian farmers to increase productivity at lower costs. This presented significant challenges for smallholder farmers, who were compelled to navigate an unregulated segment of the market and utilize market tools, such as certifications or voluntary standards. Consequently, there was a heightened exploitation of rural workers and coffee pickers, as labor costs needed to be reduced. This situation led to the growth of informal contracts within the Colombian coffee economy despite existing labor laws and regulations.

Gomez-Cardona [8], through a study in southwest Colombia, highlights how certifications such as Organic, Fair Trade, and others, which are necessary to add value in an unregulated and extremely competitive market, imposed new restrictions on farmers. The efforts made to comply with these certifications have had a detrimental impact on the daily lives and working conditions of farmers, leading to a significant deterioration, particularly for small farmers who have been affected. Consequently, Colombian farmers experienced a dual trend: some abandoned coffee cultivation to seek alternative forms of income, while others opted to self-organize in new cooperative structures to bypass traditional certifications and establish trust-based relationships between producers and consumers.

Rodriguez et al. [34] emphasize the negative consequences of the liberalization process, including declining prices and the increased investments required to compete in global markets. These factors led many Colombian coffee farmers to seek alternatives in their pursuit of economic stability, which had profound consequences on the Colombian economy, society, and environment. As a result, many farmers migrated from rural to urban areas in search of livelihoods, while others resorted to unsustainable activities such as gold mining.

Bair and Hough [30] also express criticism regarding the effects of the liberalization process. Through a comparative analysis of the consequences in Mexico and Colombia, they shed light on how this process accelerated land concentration and exacerbated local and global inequality. However, unlike other scholars, they argue that these effects were not solely caused by the liberalization process but were also influenced by previous dynamics of land concentration and privatization that had been supported and managed by the Colombian state for several decades. These dynamics led to a progressive dispossession of small and medium farmers and favored the concentration of land and capital in the coffee sector. From their perspective, the liberalization process merely intensified and amplified existing dynamics and trends within the Colombian economy.

4.3.2. Effects of the Peace Process on the Colombian Coffee Sector

The peace process between guerrilla forces, the Colombian state, and paramilitary groups began in 2016 and is still ongoing. This process has had significant economic consequences, particularly for the coffee sector, which was severely impacted by the civil war and subsequent territorial fragmentation. The peace process facilitated the expansion and consolidation of cooperative networks through improvements in equipment, infrastructure, and communication routes, thereby facilitating better organization within the coffee production chain. Several scholars highlight the positive effects of the peace process [8,31,32,33]. Barrios et al. [31] provide a systemic analysis of the Colombian war and post-war economy, focusing on the effects of the peace process on the coffee sector. According to their findings, the cultivation of coca, which shares soil characteristics with coffee crops, became prevalent during the conflict, as farmers were coerced or compelled to switch their crops and share profits with the war actors who used coca production as a source of funding. This resulted in a decline in coffee production and a loss of control for farmers over their territory and economic activities. With the peace process, the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC), supported by the Colombian government, facilitated land redistribution and provided soft loans to farmers’ families, enabling them to reintegrate into the official economy. Additionally, the FNC supported fair trade initiatives that played a crucial role in promoting cooperation, stability, and economic opportunities on both local and global scales. These initiatives helped undermine the war economy, offering farmers a viable economic alternative and fostering a reconciliation strategy through the creation of new cooperative networks and local markets.

Bonnet [32] traces the history of the Colombian economy over the past decades and emphasizes the role of certain corporations in promoting peace talks among conflicting forces. Specifically, Bonnet highlights the efforts of the Consejo Gremial Nacional (CGN) during Uribe’s administration (2008–2010). The CGN, which includes coffee enterprises, actively denounced the detrimental effects of the war, highlighting how the conflict exacerbated the consequences of the global economic crisis on the Colombian economy. These efforts explain the CGN’s role in sustaining a peace agreement from 2000 to 2016.

Navarrete et al. [33] offer a distinct perspective on the peace process and its consequences. They emphasize the role of Rural Producer Organizations (RPOs) in the peacebuilding process. In their case study of the Colombian municipality of Planada, the authors demonstrate how the left-wing guerrilla forces of FARC-EP played a crucial role in promoting the establishment of Rural Producer Organizations (RPOs) to facilitate agrarian reform and sustain the revolutionary movement. Furthermore, these revolutionary forces in Planada prohibited opium cultivation and instead encouraged the production of coffee and other crops. The empowered and self-organized rural communities, regardless of their affiliations, have been instrumental in fostering peace through their productive activities. Economic activity has become a resilience strategy to distance themselves from the conflict [33]. Despite challenges such as low and volatile international market prices and rising input costs, coffee farmers in Planada persevered and formed associations that played a decisive role in facilitating dialogue between conflicting forces. The commencement of peace talks in 2012 allowed these farmers’ associations to establish relationships with potential partners, exporters, and buyers. The peace process initiated in 2016 has been instrumental in creating and expanding commercial relationships. Navarrete et al. [33] also emphasize the significant role of intermediary institutions, such as third-party organizations and foreign companies, in supporting the efforts of growers’ associations through the establishment of certified supply chains. Despite the critical literature on the effects of certifications, the scholars’ case study demonstrates their potential in promoting peacebuilding and collaboration within the post-war Colombian economy [32,33,34].

4.4. Actors Discrimination along the Coffee Agro-Food Chain

Some studies focus on discriminatory practices within the Colombian coffee industry, intertwining with the previous section on asymmetries and inequalities. However, specific topics and original perspectives within these studies warrant attention.

4.4.1. Women’s Role and Female Empowerment in the Colombian Coffee Sector

The importance of women’s role in the coffee sector has been increasingly recognized in recent years, with several scholars examining its significance for understanding changes in the Colombian economy [19,35,36,37]. Cuellar Gomez [35] evaluates the effectiveness of support programs for female coffee growers’ cooperatives, drawing insights from interviews conducted with members of the Asociación de Mujeres Caficultoras Cauca (AMUCC) in Colombia. The study highlights the growing significance of female farmers in the coffee chain, emphasizing how the use of gender in global marketing can contribute to economic, social, and environmental sustainability for the communities and individuals involved. Moreover, women’s cooperative and organizational skills have proven to be effective in strengthening and consolidating farmers’ networks [35].

Pineda et al. [36] underline how changes in the cultural climate in Colombian rural areas have heightened the importance and visibility of women’s work and participation in coffee production. This increased visibility has led to greater economic and political rights for women within the coffee industry. The remarkable increase in the population of women coffee farmers in recent years has brought about significant transformations in gender dynamics within the country, as well as in various aspects of the Colombian economy, such as innovation and cooperative work. As the National Government and programs initiated by the National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC) sought to boost coffee production and address the challenges posed by the coffee crisis of 2008–2009, the active participation of women became indispensable in achieving these objectives. Their involvement not only empowered women by giving them a voice in decision-making processes, but also yielded positive outcomes that revitalized the cooperatives and their operations [36].

These aspects are also highlighted by Andrade et al. [37] in their study on female participation in the Colombian coffee sector. The authors emphasize the important role of women in promoting social responsibility, which, in turn, enables better access to differentiated markets, certified supply chains, and the strengthening of producers’ associations and cooperatives. Although women still have a relatively minor presence in decision-making positions or high value-added processes along the coffee chain, Andrade et al. [37] argue that women’s coffee associations are highly effective in fostering social responsibility practices. This represents both economic and social strength, since social responsibility leads to increased visibility in the global market and a fairer distribution of value along the supply chain.

4.4.2. Unfair Practices: Child Labor, Workers’ Exploitation, and Local Communities

Some articles shed light on the issue of unfair practices within the Colombian coffee sector, addressing illegal or criminal activities. The studies included in this section explore phenomena such as child labor, the exploitation of workers, and the impact on local communities [13,18,37,38].

Torres-Tovar et al. [38] highlight the presence of child labor in Colombia, particularly in rural areas and under informal conditions. The capacity of the Colombian state to address this issue is limited. The proliferation of informal contracts and the challenges associated with monitoring remote coffee-growing regions create obstacles for state authorities in effectively exercising control. These circumstances contribute to a lack of oversight and hinder the ability of state authorities to ensure compliance with labor and environmental regulations, further exacerbating the complexities of governing the coffee sector. The authors suggest implementing a stricter legal framework supported by robust state supervision, along with integrating agricultural training into school education in rural areas. This integration would enable children and adolescents to plan their future lives within the context of agricultural work [38].

Baquero-Melo et al. [19] shed light on the increasing exploitation of rural workers in the Colombian coffee sector, which is identified as a consequence of the liberalization process. The authors argue that the liberalization policies imposed significant pressure on Colombian farmers to increase productivity and reduce costs, which had a profound impact on medium and small farmers. Consequently, the exploitation of rural workers and coffee pickers has intensified as a means of minimizing labor expenses. Labor control practices in rural areas have led to the adoption of low wages and various contract types, including long-term, verbal, and shift-based or daily contracts. This exploitative dynamic places a substantial burden on workers across the entire coffee production chain. It is important to note that many certifications do not mandate farm owners to provide additional wages to pickers, further exacerbating the situation. Consequently, despite the presence of labor laws and regulations, informal contracts continue to be pervasive within the rural coffee economy.

Another concerning issue addressed by several scholars is the exploitation of local communities in coffee production areas [13,30,39]. Giuliani et al. [13] emphasize that specialization in coffee production at the expense of other crops poses a threat to the food security of rural communities, particularly in situations characterized by price volatility and low incomes for smallholder farmers. Zambrano et al. [39] shed light on this concern by offering a case study in the Colombian Department of Boyacá. Their research highlights how the shift from a diversified family farming model to a coffee monoculture has heightened vulnerability to food insecurity. This transition has come at the expense of other crops, leading to a reduced variety of food sources and increased reliance on a single commodity. As a result, the livelihoods of farmers and local communities have become more precarious, with implications for their ability to access an adequate and diverse food supply. To mitigate these challenges, it is crucial to generate alternatives and formulate public policies and programs that promote the cultivation of regional food crops in addition to coffee. Diversifying agricultural production in this manner will not only ensure food security for local communities, but also contribute to a more sustainable and resilient agricultural system.

4.5. Coffee Chain Downstream Actor: Consumers

Coffee Consumer Behavior in Colombia

The final section of this research explores consumer behavior regarding coffee, an important aspect that reflects the changes in Colombian society and their consequences on the economy. Three articles shed light on this issue [40,41,42].

Sepúlveda et al. [40] conducted a cross-cultural study to analyze the preferences of Spanish and Colombian consumers regarding the origin and attributes of specialty coffee, such as Fair Trade, sustainability, organic production, and gourmet quality. The study supports the idea that certifications and labels associated with specialty, Fair Trade, or gourmet coffee have a positive impact on consumers, increasing the likelihood of purchase. The authors argue that there is a growing demand for ethical attributes across various food product categories. This applies to coffee as well: an increasing number of consumers tend to prefer certified coffee despite its higher price compared to undifferentiated coffee. However, Sepúlveda et al. [40] acknowledge that the study has limitations, as it was conducted only in urban areas and did not consider important sociodemographic characteristics such as the income and education level of the participants.

Escandon-Barbosa et al. [41] conducted a study on coffee and wine consumption among millennial shoppers in Colombia, highlighting the significant influence of consumers’ social networks and online information on shaping consumer choices. They emphasized that these digital platforms provide coffee brands with a unique and privileged space to promote their products. In this context, the narrative constructed by coffee brands becomes crucial, as it has the potential to not only drive consumer preferences but also foster the growth of a sustainable regional coffee market.

Areiza-Padilla and Puertas [42] approach the issue from a different perspective by analyzing the case of Starbucks in Colombia. They argue that global coffee brands that position themselves as sustainable can promote conspicuous consumption in emerging markets. These sustainable brands create a social status that allows consumers to showcase their social standing. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in rapidly growing markets like Colombia, where the middle class seeks to adopt global habits while maintaining their traditions. Wealthy consumers increasingly prioritize sustainable consumption and often choose companies that align with sustainable practices. Recognizing this trend is crucial for developing effective marketing strategies. The authors argue that conspicuous consumption should not always be seen as incompatible with sustainability. In some cases, conspicuous consumption can even help popularize sustainable practices, benefiting both local and global sustainable supply chains and improving the incomes of smallholder farmers organized in associations and cooperatives [42].

5. Discussion

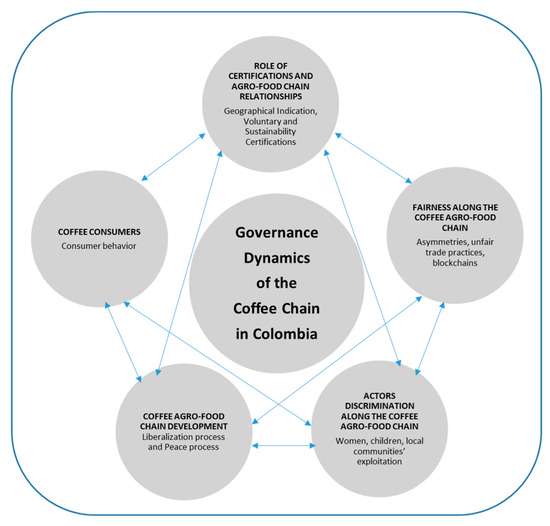

The current study presents a comprehensive review and analysis of recent articles focusing on the coffee chain governance dynamics in Colombia. The review has categorized the articles into five main areas based on their aims and themes: fairness along the coffee agro-food chain, coffee agro-food chain development, discrimination among actors in the coffee agro-food chain, coffee consumers, and the role of certifications. Each category includes sub-categories that delve into specific topics. The findings offer valuable insights into the dynamics and evolution of the Colombian coffee chain, covering all stages of the chain and providing a thorough understanding of the industry’s potential, strengths, limitations, and challenges in Colombia. The literature review identifies common issues and interrelationships among the various categories (Figure 4), enabling a multidimensional perspective that sheds light on individual problems and facilitates the formulation of future areas of research on the topic, as presented in the following sections.

Figure 4.

Interrelationships of relevant issues.

5.1. Limited Effectiveness of Certifications

One prominent observation is that scholars highlight how the coffee chain in Colombia experiences asymmetries and inequalities at local and global scales, where worker exploitation, economic sustainability, environmental impact, and food security emerge. To address these dynamics, a substantial number of articles explore the contributory role of certifications, origin labels, and voluntary sustainability standards in the coffee chain governance. Some scholars perceive these market instruments as crucial tools for mitigating inequalities and promoting fairness and sustainability in the coffee sector [4,11,14]. However, the review reveals that a significant portion of scholars express criticism regarding the effectiveness of these tools [8,9,10,12,15]. The findings suggest that these instruments alone are insufficient to address or mitigate inequalities along the global value chain. Paradoxically, in some cases, these instruments may even exacerbate existing imbalances, favoring powerful actors and creating new dependencies that threaten the autonomy and survival of smallholder coffee farmers and compromise the food security of local communities [13].

In this context, delving into the institutional framework of the coffee industry brings to light the pivotal role of associations within its structure. Gaining a deep understanding of this governance framework is essential to understand why some coffee producers, even as they remain part of the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC) and adhere to the national regulatory framework about coffee, are experiencing a certain detachment from this coffee institution [43,44]. As a reaction to this, they are actively seeking to establish alternative pathways for promotion [43,44,45].

In numerous cases, these associations try to establish non-traditional coffee production and value chains, where the understanding of quality allowed by direct knowledge and relationships transcends the conventional boundaries set by certifications. This evolution is significant as it highlights how these associations are moving beyond conventional paradigms and embracing innovative approaches that enable them to thrive in the global coffee landscape [43,44,45].

5.2. The Empowering Role of Institutions in Governing the Coffee Value Chain

Given the limited effectiveness of certifications, labels, and standards in addressing structural inequalities within the coffee industry, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive strategy that acknowledges and tackles these issues while actively involving political actors. This strategy should recognize that the root causes of inequality extend beyond the realm of market-based solutions and require broader engagement with social, economic, and political dimensions.

Several authors advocate empowering local and international institutions to establish a legal framework that ensures greater transparency and equity in supply chains [10,11,13,14]. Market tools and blockchain technologies, while valuable, are deemed insufficient and occasionally counterproductive on their own. As highlighted in relevant literature, the existence of access barriers to technologies can result in an uneven participation of producers. Despite a certain impact of digital technologies on the power dynamics within the coffee value chain (CVC), the actual involvement of producers in value creation may remain modest and contingent upon decisions made by other stakeholders. While these technologies are reshaping power structures, the transformation may entail a re-centralization of authority in the hands of new technological entities, rather than effecting genuine empowerment of producers [46]. However, if deployed in conjunction with an appropriate legal framework and supportive policies, new technologies can contribute to an effective strategy aimed at achieving greater coffee value distribution and safeguarding the weaker actors within the supply chain.

The essence of this process can be best grasped as a political undertaking rather than merely an economic one. The disparities and imbalances observed within the global coffee agri-food chain are a reflection of power dynamics that are deeply entrenched at both local and international levels [19,24]. These power relations contribute to profound class inequalities in food-producing countries and to significant disparities between the Global North and the Global South. Consequently, any concerted effort to redistribute value along the coffee chain must necessarily confront and transform these power dynamics with the overarching aim of fostering more equitable and balanced international relationships [23,24].

5.3. Colombia Economic and Political Setting and Coffee Supply Chain

Colombia’s current economic and historical–political situation appears to be favorable for strengthening the agricultural sector, and thus obviously the coffee supply chain. Following decades of violent conflict that deeply divided the country, the peace accords initiated in 2016 have restored political stability, which is already demonstrating positive effects on the Colombian economy, including the coffee sector. With the restoration of peace and security, many regions in Colombia now have the opportunity to revitalize their agricultural sectors and unlock their untapped potential, valuing the key role of coffee [8,31,33]. This return to full agricultural production, also favored by the land reform project of the current Petro’s government, which aims to allocate unused or underutilized large agricultural estates (latifundia) to small-scale producers, can have a multitude of benefits for these areas. Engaging in agricultural activities has the potential to generate not only income for farmers but also valuable employment opportunities for the local population. This, in turn, contributes to the overall social and economic development of these areas [15,33,47,48].

Furthermore, Colombia may play a strategic position within the Latin American context and value its capacity to influence dynamics and balances on the continent. With its growing political influence, Colombia may shape regional policies, promoting cooperation among neighboring countries and strengthening regional partnerships. These political developments could have profound governance implications for the coffee chain. Colombia’s growing political influence can provide a unique opportunity to shape the dynamics of the coffee industry, both domestically and internationally [24]. By leveraging its position, Colombia can advocate for fair trade practices, environmental sustainability, and social responsibility within the global coffee chain. Moreover, by investing in technologies and building capabilities for local coffee roasting, supported by adequate national policies, Colombia could effectively counterbalance the dominance of powerful actors in the coffee supply chain, particularly roasting companies. This would allow Colombia to retain more value within its borders, create local employment opportunities, and strengthen the domestic coffee industry [20,23,48].

This transformation would undoubtedly have a significant impact on both local and regional coffee consumption, thus expanding the market for coffee products. As coffee production and processing revitalizes, there would be a notable increase in the availability and quality of locally grown coffee. This, in turn, would create favorable conditions for the development of local coffee brands and stimulate the growth of the coffee industry at the regional level [41].

In this sense, the studies reviewed in this context reveal a notable trend in recent years: an increasing preference among Colombia’s middle and wealthy classes for consuming high-quality coffee [40,41,42]. While global coffee brands attract their attention, these consumers also express a desire to preserve their traditions and a sense of national identity. Capitalizing on this opportunity, Colombia can foster the creation of local coffee brands that resonate with consumers and align with their preferences.

5.4. Insights for Further Research

Given the potentialities discussed earlier, it is crucial to continue conducting in-depth studies on the coffee chain in Colombia, with a strong focus on the factors identified in this review and their interconnectedness. Understanding the interplay between economic, social, and environmental aspects in the coffee chain governance dynamics is essential for developing comprehensive approaches that account for its multifaceted nature. By recognizing the interdependencies among these factors, it becomes possible to design interventions that foster sustainable and equitable development throughout the entire coffee value chain.

However, it is important to acknowledge that there are gaps in the existing literature. First, while many authors have meticulously examined specific aspects of the issue, there remains a lack of scholarly work that adopts an extensive multidisciplinary perspective. To fully grasp the complexities of the global coffee chain, Colombia’s central role within it, and the current historical and political context of the country, it is key to integrate these elements into a comprehensive analysis. Such an analysis would not only capture the existing limitations and opportunities but also define new political models and coffee supply chains that facilitate the full realization of the sector’s potential.

Second, another area that requires attention, closely linked to the previous gap, is the scarcity of quantitative studies that analyze the impacts of transformations in the Colombian coffee industry on land use and local communities. While previous studies by scholars such as Giuliani et al. [13] and Zambrano et al. [40] have provided valuable insights into the impact of monoculture in the coffee industry, there is still a need for further investigation to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how this trend affects the economy and food security of local communities. Comparing this impact with the impact of more diversified models of agriculture, such as those proposed by the agroecological paradigm, is of paramount importance. The agroecological paradigm emphasizes diversified agriculture and bottom-up decision-making processes, promoting ecological sustainability and social equity. Conducting research that investigates the comparative impacts of different agricultural approaches to coffee production is urgent in the current historical and cultural context. The ongoing intense debate on alternative agricultural paradigms to the dominant agro-industrial model highlights the need to explore more sustainable models of agriculture.

Moreover, adopting this approach could effectively address some of the negative consequences of the liberalization process, which have been highlighted by various authors and currently impact the coffee sector. One such consequence is the gradual transfer of power and control to the actors managing the key hubs of the global supply chain. To counteract this trend, it would probably be highly beneficial to reallocate some political and institutional control within the supply chain, prioritizing endogenous and bottom-up development processes rather than relying solely on downstream buyers. Given the importance and potential impact of this perspective, it is crucial to foster further research that delves into its practical implications. Through comprehensive investigations and the collection of empirical evidence, it is possible to uncover concrete examples that improve the effectiveness of strategies that promote governance dynamics aimed at retaining power locally. The insights generated from such research might help decision-making processes and shape policy discussions, leading to positive changes in the coffee chain.

In this regard, facilitating the self-organization of small coffee producers into associations and cooperatives, with the support of targeted economic policies aimed at protecting coffee farmers in their countries of origin, could prove to be an effective strategy [10,47,49]. From this perspective, the ongoing land reform initiatives and the redistribution of large tracts of fertile land to small producers organized in cooperatives, such as coffee, but not exclusively, are developments that warrant attention and further investigation. These processes hold great potential to reshape power dynamics within the coffee chain, empowering marginalized actors and fostering a more equitable distribution of resources [23,26,50]. By examining the outcomes and implications of these initiatives, researchers can gain valuable insights into the effectiveness of alternative governance models and their impact on the socioeconomic landscape of coffee-producing regions. Such analysis can contribute to the design of more inclusive and sustainable approaches that prioritize the well-being of smallholder coffee farmers, strengthen local communities, and foster a fairer and more resilient coffee industry.

6. Conclusions

The conducted review has provided a comprehensive overview of the recent governance issues of the Colombian coffee chain, shedding light on its structure and dynamics at the local and global levels. The search string proved to be effective. The research articles addressed a wide range of issues impacting the coffee value chain in Colombia. Through an in-depth analysis and discussion of the findings, the review has successfully identified connections between the identified problems, enabling a better understanding of the Colombian coffee sector’s limitations and potential.

The authors have prominently highlighted the presence of asymmetries and inequalities throughout the coffee agro-food chain, as well as the economic and political transformations that have shaped the coffee sector in the country in recent decades. Given Colombia’s status as the third-largest coffee-producing nation in the world, its current economic and political situation makes it a compelling case study for understanding present and future changes in the coffee sector. The review and analysis of the results have not only examined ongoing trends and challenges within the country but also identified possible common governance dynamics shared by other coffee-producing nations within the global supply chain.

Consequently, Colombia emerges as a privileged observatory for understanding contradictions, bottlenecks along the chain, and potential strategies for their resolution. Thus, it is important to continue studying the coffee sector in Colombia from a multidisciplinary perspective that connects aspects of the economic agro-food chain with environmental, social, and political factors. Such an approach will provide valuable insights into the intricate interplay between these dimensions and contribute to developing comprehensive solutions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su151813646/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.S.; validation, A.S.; formal analysis, A.F.; investigation, A.F.; data curation, A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Rafforzamento della capacita’ istituzionale per favorire la competitività e sostenibilità del settore agricolo e lo sviluppo delle aree rurali in Colombia” (Strengthening institutional capacity to foster the competitiveness and sustainability of the agricultural sector and the development of rural areas in Colombia), funded by AGENZIA ITALIANA PER LA COOPERAZIONE ALLO SVILUPPO (AICS), EUROPEAN UNION, FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS (FAO)—Cooperation Program DRET II, Contract number: AID 012184/01/0.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Borrella, I.; Mataix, C.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Smallholder Farmers in the Speciality Coffee Industry: Opportunities, Constraints and the Businesses that are Making it Possible. IDS Bull. 2015, 46, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Coffee Organization (ICO). Coffee Development Report: The Future of Coffee; ICO: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre. The Coffee Guide, 4th ed.; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, X.; Lambin, E.F. Linking Globalization to Local Land Uses: How Eco-Consumers and Gourmands are Changing the Colombian Coffee Landscapes. World Dev. 2013, 41, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Monroy, L.; Potts, S.G.; Tzanopoulos, J. Drivers influencing farmer decisions for adopting organic or conventional coffee management practices. Food Policy 2016, 58, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volsi, B.; Telles, T.S.; Caldarelli, C.E.; Da Camara, M.R.G. The dynamics of coffee production in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Estrella Chong, A.; Grabs, J.; Kilian, B. How Effective is Multiple Certification in Improving the Economic Conditions of Smallholder Farmers? Evidence from an Impact Evaluation in Colombia’s Coffee Belt. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 56, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cardona, S. Las tensiones de los mercados orgánicos para los caficultores colombianos. Caso Val. Cauca. Cuad. Desarro. Rural. 2012, 9, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Beuchelt, T.; Zeller, M. The role of cooperative business models for the success of smallholder coffee certification in Nicaragua: A comparison of conventional, organic and Organic-Fairtrade certified cooperatives. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Penker, M.; Vogl, C.R.; Samper-Gartner, L.F. Can origin labels re-shape relationships along international supply chains?—The case of Café de Colombia. Commons J. 2015, 9, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellema, W.; Casanova, A.B.; González, C.; D’Haese, M. The effect of specialty coffee certification on household livelihood strategies and specialisation. Food Policy 2015, 57, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, M.; Blackman, A. Is eco-certification a win–win for developing country agriculture? Organic coffee certification in Colombia. World Dev. 2016, 82, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]