Methods of Cyclist Training in Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

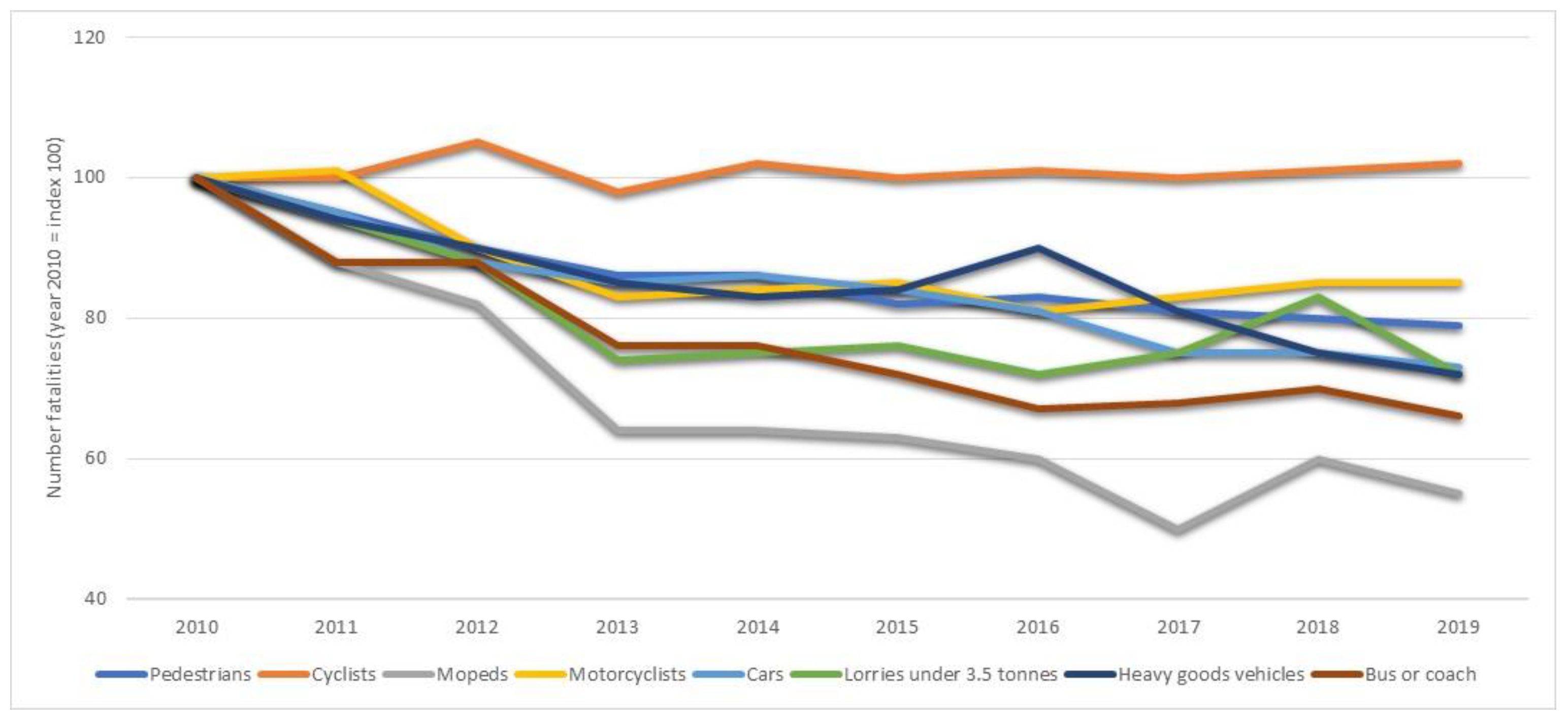

2. The State of Cycle Safety in European Union

3. Cycling Education in Europe

- Fundamental bike handling skills:

- Maintaining balance.

- Pedaling.

- Steering.

- Braking.

- Safety skills:

- Scanning the environment (e.g., moving one’s head).

- Merging into traffic.

- Braking to halt at traffic signals and stop signs.

- Signaling maneuvers when turning [8].

3.1. The Netherlands

3.2. Germany

3.3. England

3.4. Austria

3.5. Slovenia

- Attaining theoretical knowledge and assessing comprehension.

- Practicing cycling skills in controlled environments.

- Experiencing hands-on riding within actual traffic scenarios [23].

3.6. Poland

- The role of the coordinator and teaching staff assisting students in obtaining a bicycle card.

- The curriculum content covered in preparation for acquiring a bicycle card.

- The duration of each examination segment.

- The format of the theoretical examination, encompassing question count and knowledge scope.

- The location of the practical examination.

3.7. Italy

4. Comparative Analysis of Training Methods, Rules, and Regulations for the Training and Examination of Cyclists

5. Conclusions

- Prioritizing the education of children and adolescents, recognizing their role as bearers of knowledge to future generations.

- Undertaking a long-term process of standardizing cycling education that aligns with current needs and prevailing standards.

- Elevating awareness about the significance of cycling education among parents, as their behaviors and practices serve as models for their children.

- Infusing safe cycling content into all levels of education, ranging from kindergarten to high school, within defined and consistent time frames.

- Establishing a governing body responsible for cyclist education that acts as a training coordinator, and defines and enforces standards and prerequisites.

- Amending legal provisions regarding age limits for independent cycling.

- Intertwining theory and practice during cycling education sessions.

- Facilitating opportunities for cycling practice, initially within secure and controlled environments and subsequently in real traffic settings during training.

- Advocating the core importance of cycling proficiency testing and elevating its prominence, as a pivotal stage in advancing road safety.

- Ensuring that instructors of bicycle courses are well-prepared and adhere to specific standards.

- Implementing mandatory annual refresher training for teachers and instructors.

- Evaluating the knowledge and skills of trainers through mandatory competency examinations.

- Conducting recurring campaigns aimed at promoting safe cycling practices for both children and adults.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Road Safety Observatory. Facts and Figures Cyclists; European Commission, Directorate General for Transport: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mocniak, K. Kto chroni niechronionych? In Sytuacja Pieszych i Rowerzystów w Warszawie na Tle Polski i Europy; Zielone Mazowsze: Warszaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, A.; Kahlmeier, S.; Gotschi, T. Exposure-Adjusted Road Fatality Rates for Cycling and Walking in European Countries; Discussion Paper; The International Transport Forum: Zurich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Road Safety Thematic Report—Fatigue; European Road Safety Observatory, European Commission, Directorate General for Transport: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Law Commission. In Proceedings of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Vienna, Austria, 23 May 1969.

- DaCoTA. Pedestrians and cyclists. In Deliverable 4.8l of the EC FP7 Project DaCoTA; DaCoTA: Bryn Mawr, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Speed management. In Proceedings of the European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Paris, France, 1–3 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J. Bicycle Safety Education for Children From a Developmental; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holland-Cycling.com. Traffic Exam Improves Road Safety for Children. 2018. Available online: https://www.holland-cycling.com/blog/292-traffic-exam-improves-road-safety-for-children (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Veiligverkeer Assen. Praktisch Verkeersexamen 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.vvnassen.nl/Praktisch-verkeersexamen (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Verkeer op School. Tien Weetjes over Het Grote Fietsexamen. 2021. Available online: https://www.verkeeropschool.be/nieuws/tien-weetjes-over-het-grote-fietsexamen/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Wikipedia. Verkehrserziehung. 2022. Available online: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verkehrserziehung (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Dojczland.info. Karta Rowerowa w Niemczech—Najważniejsze Informacje! 2020. Available online: https://dojczland.info/karta-rowerowa-w-niemczech/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Wikipedia. Jugendverkehrsschule. Available online: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jugendverkehrsschule (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Die Rheinpfalz. Jugendverkehrsschule: Radführerschein Auch in der Pandemie Möglich. 2020. Available online: www.rheinpfalz.de/lokal/kaiserslautern_artikel,-jugendverkehrsschule-radf%C3%BChrerschein-auch-in-der-pandemie-m%C3%B6glich-_arid,5132053.html?reduced=true (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Deutshe Verkehrswacht. Über Uns. 2022. Available online: https://deutsche-verkehrswacht.de/ueber-uns/ (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Department for Transport. National Standard for Cycle Training; Driver & Vehicle Standards Agency: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Bikeability Trust. Bikeability Delivery Guide; The Bikeability Trust: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bikeability. About Us. 2020. Available online: https://www.bikeability.org.uk/about/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Oesterreich.gv.at. Radfahrprüfung. 2022. Available online: https://www.oesterreich.gv.at/themen/freizeit_und_strassenverkehr/rad_fahren/1/Seite.610420.html (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Jugendrotkreuz. Das Jugendrotkreuz im Kindergarten. 2021. Available online: https://www.jugendrotkreuz.at/oesterreich/angebote/radfahrpruefung/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- MeinBezirk.at. Jugendrotkreuz: Risiko für Badeunfälle Heuer Besonders Hoch. 2021. Available online: https://www.meinbezirk.at/perg/c-freizeit/jugendrotkreuz-risiko-fuer-badeunfaelle-heuer-besonders-hoch_a4746239#gallery=null (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Javna Agencua Republike Slovenue Za Varnost Prometa. Kolesarski Izpiti. Available online: https://www.avp-rs.si/preventiva/prometna-vzgoja/programi/kolesarski-izpiti/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Žlender, B. Koncept Usposabljanja za Vožnjo Kolesa in Kolesarskega Izpita v Osnovni Šoli; Ministrstvo za Izobraževanje, Znanost in Šport: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K. Inventory and Compiling of a European Good Practice Guide on Road Safety; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Edukacji Narodowej. Podstawa Programowa Kształcenia Ogólnego z Komenatrzem: Szkoła Podstawowa, Technika; Dobra Szkoła: Warszaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minister Transportu, Budownictwa i Gospodarki Morskiej. Rozporządzenie Ministra Transportu, Budownictwa i Gospodarki Morskiej z Dnia 12 Kwietnia 2013 r. w Sprawie Uzyskiwania Karty Rowerowej (Dz.U. z 2013 r., Poz. 512); Sejm: Warszaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Normattiva. Decreto Legislativo 30 Aprile 1992 n. 285 e Successive Modificazioni; Normattiva: Rome, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Federazione Italiana Ambiente e Bicicletta. Chi Siamo. Available online: https://fiabitalia.it/fiab/chi-siamo/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Deutscher Bundestag. Straßenverkehrs-Ordnung (BGBl. I S. 367); Bundesanzieger: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- City of Vienna. Traffic Rules and Regulations for Cyclists. Available online: https://www.wien.gv.at/english/transportation-urbanplanning/cycling/traffic-rules.html (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Republika Slovenija Ministrstvo Za Notranje Zadeve. Policija. Varno na Kolo. Available online: https://www.policija.si/index.php/component/content/article/156/801-varno-na-kolo (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- NederlandersFietsen. Wetgeving Fietsers. Available online: https://nederlandersfietsen.nl/wetgeving-fietsers/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz. Straßenverkehrs-Zulassungs-Ordnung (StVZO); Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit und Bundesministerium des Innern nach Anhörung der Beteiligten Kreise: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rechtsinformationssystem Des Bundes. Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Verkehr, Innovation und Technologie über Fahrräder, Fahrradanhänger und zugehörige Ausrüstungsgegenstände (Fahrradverordnung). 2023. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=20001272 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- GOV.UK. General Product Safety Regulations 2005: Great Britain. 2005. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2005/1803/contents/made (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Javna Agencija Republike Slovenije Za Varnost Prometa. Varno Kolo. Available online: https://www.avp-rs.si/preventiva/preventivne-akcije/varnost-kolesarjev/varno-kolo/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Minister Infrastruktury. Rozporządzenie Ministra Infrastruktury z Dnia 31 Grudnia 2002 r. w Sprawie Warunków Technicznych Pojazdów Oraz Zakresu Ich Niezbędnego Wyposażenia; Sejm: Warszaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Voor Veilig Verkeer. Fietsen op Een Voetpad of Zebrapad, Mag Dat? Available online: https://www.veiligverkeer.be/inhoud/fietsen-op-een-trottoir-of-zebrapad-mag-dat/ (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Allgemeiner Deutsher Fahhrad-Club. Verkehrsrecht für Radfahrende. Available online: https://www.adfc.de/artikel/verkehrsrecht-fuer-radfahrende (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- British Cycling. Tips for Cycling with Kids. Available online: https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/knowledge/article/20200529-Get-Started-Tips-for-cycling-with-kids-0 (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Minister Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji; Minister Transportu i Gospodarki Morskiej; Minister Obrony Narodowej. Ustawa z Dnia 20 Czerwca 1997 r. Prawo o Ruchu Drogowym (Dz. U. 1997 Nr 98 Poz. 602); Sejm: Warszaw, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatiadis, N.; Pappalardo, G.; Cafiso, S. A comparison of bicyclist attitudes in two urban areas in USA and Italy. In Data Analytics: Paving the Way to Sustainable Urban Mobility, Proceesdings of the CSUM 2018—Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Skiathos Island, Greece, 24–25 May 2018; Nathanail, E., Karakikes, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 879, pp. 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Description of Contents | Division into Chapters | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role 1 | Prepare for a journey | How to prepare myself and the cycle, and plan a journey | 1.1. Prepare myself for a journey 1.2. Preparing the cycle for a journey 1.3. Plan a journey |

| Role 2 | Ride with control | How to set off, ride, and stop the cycle | 2.1. Set off and stop the cycle 2.2. Ride safety and responsibly |

| Role 3 | Use the road in accordance with the highway code | How to negotiate roads and junctions and comply with signals, signs, and road markings | 3.1. Negotiate roads safely and responsibly 3.2. Comply with signals, signs, and road markings |

| Role 4 | Ride safely and responsibly in the traffic system | How to share the road with others | 4.1. Interaction with other road users 4.2. Minimize risk when cycling |

| Role 5 | Improve cycling | Learn from experience and keep up to date with changes | 5.1. Review and improve your cycling practice |

| Role 6 | Deliver cycle training | Enable others to cycle safety and responsibly | 6.1. Prepare to train learners 6.2. Design cycle training sessions 6.3. Enable safe and responsible cycling 6.4. Manage risk to maximize learning 6.5. Improve professional practice 6.6. Train instructors to deliver cycle training |

| Description | Maximum Number of Participants per Instructor | Minimum Time Requirements | Recommended Age Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | It teaches basic bicycle handling skills in a controlled, traffic-free environment | 12 | 2 h | From 7 to 9 years |

| Level 2 | It teaches students how to cycle along planned routes on roads with less traffic | 6 | 6 h | From 9 to 11 years old |

| Level 3 | Provides participants with the ability to cope with a variety of traffic conditions; training is conducted on normal traffic roads with advanced features and systems | 3 | 2 h | Over 14 years old |

| Success Criteria | Penalty Points | |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | At least 75% of possible points, including all tasks for 2 points. | None. |

| Practical—driving around the maneuvering area | Overcoming 50% of the obstacles without error, which must include stopping, not moving an object, and slalom. | For each contact of the ground with a foot, for each time touching the boundary line of the maneuvering area, for each loss or movement of a peg cone or mark, for each omission of an obstacle, for knocking down the first stick in the final obstacle or knocking down the last stick in the final obstacle, for knocking down all obstacles, for destroying an obstacle that should not be touched by the examinee at all. |

| Practical—driving in traffic | Credit is granted if the student has not collected more than 25% negative points and did not make cardinal errors such as forcing the right of way, incorrect signaling for a turning maneuver, etc. | 1. Driving technique: failure to check the suitability of the bicycle for riding, incorrectly getting on the bike, getting off the bike, incorrect one-handed driving, incorrect driving straight ahead, abnormal stop. 2. Driving on the road: too large a bend when turning into a road with priority, too much distance from the edge of the road, incorrect use of the bicycle path, incorrect passing of a railway crossing. 3. Turning right: lack of hand signaling of the intention to change direction. 4. Turning left: failure to turn and look backwards before turning left, no hand signaling of the intention to turn left, incorrect arc when turning. 5. Passing: failure to look back before making a turning maneuver, hindering traffic coming from the opposite direction, wrong turn right. 6. Behavior towards pedestrians: obstructing the passage of pedestrians through the pedestrian crossing. 7. Intersection: disregarding the STOP sign, failure to comply with the applicable rules, wrong roundabout driving. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | In grades 7 and 8 of primary school, children take a bicycle test which consists of a mandatory theoretical part and a practical part which takes place in traffic, but the decision to conduct it is up to the school. |

| Germany | Children take the bicycle test in the 4th grade, which is usually when they are 10 years old, and the teacher conducting the classes decides whether a child has mastered the safe riding and first aid elements, and whether the results of the theory test and practical test are satisfactory. The exam consists of a theoretical and a practical part. |

| Austria | Children as young as 9 who are in 4th grade, or those who have just turned 10, can take the voluntary bicycle test. The test is divided into a theoretical and a practical part. A positive result from the voluntary bicycle test entitles children to independently ride a bicycle on public roads without a guardian. |

| England | The idea of organizing bicycle exams, which had been practiced in the past, was abandoned. The current training system does not provide for them and focuses on the implementation of the assumptions of training levels. |

| Slovenia | The exam usually takes place in the 5th grade of primary school. Children who pass the bicycle exam receive a bicycle card. The exam usually takes place in the 5th grade of primary school. |

| Poland | Most often, it is carried out in the 4th grade (some institutions organize it in the 5th grade) of primary school. A positive result on the theoretical and practical parts entitles the student to receive a bicycle card. |

| Italy | The current training system does not provide for bicycle exams and focuses on the implementation of the assumptions of training levels. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | It takes place in real traffic, on a route designated by the organizers. |

| Germany | The practical part of the exam usually takes place in youth movement schools. |

| Austria | The practical exam is conducted in real traffic. |

| England | There is no bicycle exam. The training is carried out successively in the following environments: free from traffic (level 1), on roads with less traffic (level 2), on roads with normal traffic (level 3). |

| Slovenia | The first part of the exam takes place in the maneuvering area and the second in real traffic. |

| Poland | The place is determined by the school principal. Depending on the infrastructure at the facility’s disposal, it is a maneuvering area, a school playground, a gymnasium, a schoolyard, or a traffic town. |

| Italy | There is no bicycle exam. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | Before the start of the practical exam, the ability to check the technical condition of the bicycle is assessed. One by one, children cover the bicycle route in traffic, which is determined individually by the organizers. The course of the route and specific tasks are made public in good time. The skills that would need to be tested are not specified. During the exam, it is generally checked whether children apply knowledge and rules of the road in practice. |

| Germany | The exam consists of driving a designated route in a traffic town; in most cases children can decide on their own which route they want to take. The scope of the tasks to be examined has not been specified; the policeman observes the driving style of students and assesses any traffic violations. |

| Austria | There are no specific skills that a bike test must include. It is up to the organizers of the exam how it will be run, its route, and what it will check. |

| England | There is no bicycle test in England, but the “National Standard” defines what a cyclist should know and be able to do at each level of training. Bikeabilty instructors prepare a schedule of classes individually for participants, taking into account and meeting the standards set for each level. |

| Slovenia | The document “Concept of Bicycle Training and Bicycle Examination in Primary School”, issued by the Ministry of National Education, Science, and Sport, defines the objectives and thematic areas that teachers should raise during the course. In addition, it provides the criteria for passing individual parts of the bicycle exam (Table 3). The questions on the theory test are drawn from a pool of questions which the person taking the exam can prepare for in advance. |

| Poland | The new core curriculum for the subject of technology presents the required skills that a primary school student should have after completing the training. The role of the teacher conducting the subject is to draw up regulations that specify the conditions for applying for a bicycle card and the procedure for obtaining it. The scope and rules for obtaining a bicycle card by persons who are not primary school students are specified in the Regulation of the Minister of Transport, Construction, and Maritime Economy of 12 April 2013 on obtaining a bicycle card. The organizer is responsible for the questions in the theoretical exam and the course of the practical exam. The form of the exam must comply with the provisions in the regulations. |

| Italy | There is no bicycle exam. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | Does not exist. Children who pass the bike license exam receive a diploma. |

| Germany | After passing the exam, students receive a bicycle license, which is symbolic and not enforced by German traffic law. |

| Austria | Its possession entitles children over 10 years of age to ride in traffic without a guardian. |

| England | Does not exist. With the completion of each Bikeability level, the student receives a diploma with congratulations on completing the course. |

| Slovenia | Upon successfully passing the bicycle examination, the student is granted a bicycle card, enabling children below the age of 14 to independently ride a bicycle [24]. |

| Poland | It is an official document that authorizes persons under 18 to ride a bicycle. It is issued for free and indefinitely [27]. |

| Italy | Does not exist. With the completion of each course, the student receives a diploma with congratulations on completing the course. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | School teachers and Traffic Garden employees are responsible for education. |

| Germany | Lessons on road safety are taught by school teachers, while traffic guards and the police are responsible for classes in Youth Traffic Schools. |

| Austria | The voluntary bicycle test is carried out in cooperation with the police. |

| England | The Bikeability program is run by specially trained instructors [19]. |

| Slovenia | A trained teacher in cooperation with parents, the police, and the municipal council for prevention and education in road traffic [23]. |

| Poland | “The classes are conducted by a teacher with specialist training in road traffic organized free of charge in the provincial road traffic center, a police officer or a retired police officer with specialist training in road traffic, an examiner or an instructor” [27]. |

| Italy | The classes are conducted by a teacher coming for free from a private institution. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | Dutch do not wear helmets, nor are they obliged to do so. Cyclists there are convinced that the rules of the road and infrastructure design will protect them against injuries. |

| Germany | There is no obligation to wear a helmet. The German traffic police focuses on education by running campaigns promoting helmet wearing [30]. |

| Austria | Children under the age of 12 must wear a helmet when riding a bicycle, as well as those traveling in a seat behind the cyclist [31]. |

| England | British law does not require cyclists to wear a helmet, but the Highway Code suggests wearing a helmet with particular attention to its correct size and secure fastening. |

| Slovenia | A cyclist under the age of 18 must wear an approved protective helmet on his head while riding, and the same applies to a child riding on a bicycle as a passenger [32]. |

| Poland | There is no law in Poland that would require cyclists to wear a helmet. |

| Italy | The Highway Code [28] includes an obligation to wear a helmet, for electric bicycles and traditional bicycles, only for children and teenagers up to the age of 14. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands |

|

| Germany |

|

| Austria |

|

| England | The rear hand brakes are placed on the left side, and the front ones on the right side. Bell. White or yellow reflectors on both sides of each wheel or tire. White wide-angle headlight or front lamp. Red wide-angle rear reflector. Yellow reflectors front and rear on each pedal [36]. |

| Slovenia | Working front and rear front brakes. White light at the front for road lighting and red light at the rear. Pedal reflectors. Bell. Properly inflated tires. Properly adjusted steering wheel and seat height. It is also recommended that a bike have mudguards, a chain guard, and a rack [37]. |

| Poland | In front—at least one position light of white or selective yellow color (a flashing light may be used). At the rear—at least one red reflector with a shape other than a triangle and at least one red position light. At least one effective brake. A bell or other non-shrill sound warning signal. From October 8, 2013, cyclists do not need to have lights on their bikes if they are not going to ride after dark. This does not apply to the red rear reflector, which must be permanently installed [38]. |

| Italy | According to the Highway Code [28], in order to be able to circulate, bicycles must necessarily be equipped with a bell, front lights, rear lights and reflectors, and reflectors on the pedals and side. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| All analyzed countries | None of the analyzed countries require cyclists to wear a reflective vest. |

| Country | Description |

|---|---|

| The Netherlands | There is no age limit that would entitle children to move independently on the road. Children under the age of 10 can use the footpaths for cycling [39]. |

| Germany | Children up to the age of 8 must ride on the pavement. At this age, they may start to use separate bike lanes if they are available for use. However, at the age of 10, they can start driving independently in road traffic. The German legislature explains this by saying that children under the age of 10 are particularly at risk in road traffic because they have not yet acquired the necessary knowledge and skills [40] |

| Austria | A child under the age of 12 may not ride a bicycle in traffic without being accompanied by a responsible person who is at least 16 years old. Children between the ages of 10 and 12 may ride alone on the streets only if they have passed the voluntary bicycle test and have their bicycle license as proof [31]. |

| England | In England, there are no legal age limits for when children can start cycling on the street. The decision is up to the parents and is based on observation of cycling skills and awareness of the dangers on the road. Although there are no penalties for unaccompanied driving under the age of 10, this does not mean that such children should drive in traffic unaccompanied by their parents or guardians [41]. |

| Slovenia | If a child does not have a bicycle card, he/she cannot ride a bicycle in road traffic until the age of 14 [23]. |

| Poland | Children under the age of 10 cannot ride a bicycle without the supervision of an adult; they are treated by law as pedestrians. Therefore, they must ride on the pavement. A positively passed exam for a bicycle license entitles children and youth aged 10–18 to ride a bicycle on their own on the street. Adults can ride a bike without any limits or additional permissions [42]. |

| Italy | In Italy, there are no legal age limits for when children can start cycling on the street but a child under the age of 14 is under parental responsibility. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wachnicka, J.; Jarczewska, A.; Pappalardo, G. Methods of Cyclist Training in Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914345

Wachnicka J, Jarczewska A, Pappalardo G. Methods of Cyclist Training in Europe. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914345

Chicago/Turabian StyleWachnicka, Joanna, Alicja Jarczewska, and Giuseppina Pappalardo. 2023. "Methods of Cyclist Training in Europe" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914345

APA StyleWachnicka, J., Jarczewska, A., & Pappalardo, G. (2023). Methods of Cyclist Training in Europe. Sustainability, 15(19), 14345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914345