Determinants of an Environmentally Sustainable Model for Competitiveness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How do LSPs implement environmental practices?

- How do human–environment connections foster sustainability performance?

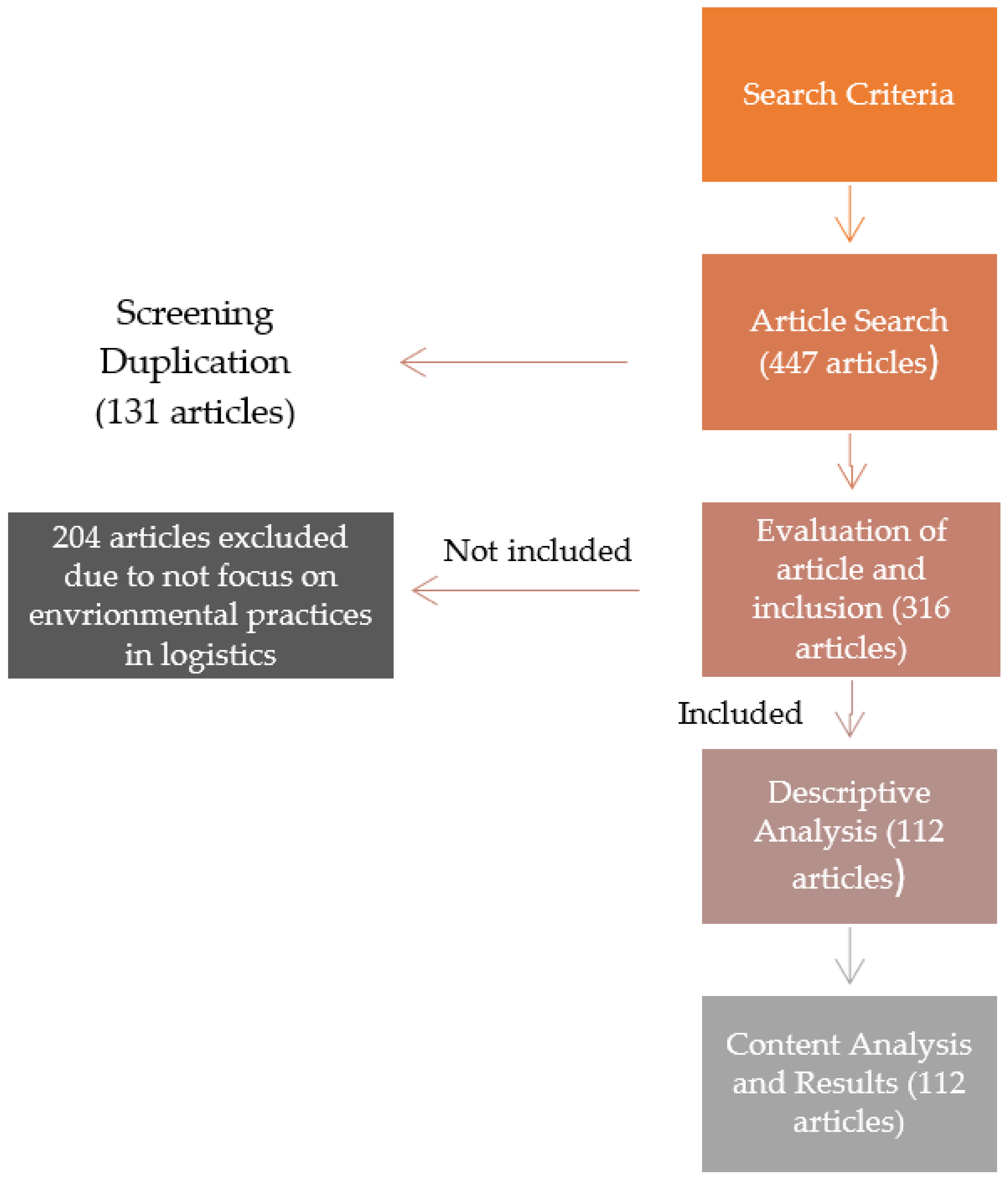

2. Methodology

- How do LSPs implement environmental practices?

- How do human–environment connections foster sustainability performance?

2.1. Paper Overview

2.2. Past Review Papers

3. Results

3.1. Implementation of Environmental Practices by LSPs

- -

- Mission and vision—the extent of a firm vision and mission for sustainability;

- -

- Structure and formal system—the extent of legal efforts toward environmental sustainability;

- -

- Organizational culture and proses—the extent of culture, knowledge, and awareness or education and training about ethical and environmental operations;

- -

- Competitive strategies—the extent of environmental capabilities, systems, or practices as sources of competitive advantage;

- -

- Technology competencies—the extent of advanced or innovative tools, green technologies, and logistics innovation focused on environmental sustainability to handle environmental issues, more significant freight volumes, speed the time taken to deliver, and lower the delivery cost.

3.2. Human–Environment Connection

3.3. An Environmentally Sustainable Model

4. Discussions and Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sallnäs, U.; Huge-Brodin, M. De-greening of logistics? Why environmental practices flourish and fade in provider-shipper relationships and networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 74, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Green logistics performance and sustainability reporting practices of the logistics sector: The moderating effect of corporate governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, S.; Yousaf, H.Q.; Ahmed, M.; Rehman, S. Effects of green human resource management on green innovation through green human capital. Environmental knowledge, and managerial concern. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. Environmental performance and human development for sustainability: Towards to a new Environmental Human Index. Sci. Total Env. 2022, 838, 156491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, K.; Loreau, M. A model of Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and opportunities in promoting human well-being and environmental sustainability. Ecol. Modelling. 2023, 475, 110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, N. Explicating sustainable development growth and triumph: An Islamic-based sustainability model. In Handbook of Research on SDGs for Economic Development, Social Development, and Environmental Protection; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 120–143. [Google Scholar]

- El Baz, J.; Laguir, I. Third-party logistics providers (TPLs) and environmental sustainability practices in developing countries. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, N. Green Logistics Practices and Sustainable Business Model. In Handbook of Research on the Applications of International Transportation and Logistics for World Trade; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 354–366. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, H.; Norrman, A. The Physical Internet–review, analysis and future research agenda. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bask, A.; Rajahonka, M. The role of environmental sustainability in the freight transport mode choice: A systematic literature review with focus on the EU. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 560–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: Systematic literature review and research directions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 53, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Santoro, L.; Thomas, A. Environmental sustainability in third-party logistics service providers: A systematic literature review from 2000–2016. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, N.; Asaari, M.H.A.H. Leadership attributes and their impact on work-related attitudes. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, N. A sustainable leadership model: Intelligence and innovation of knowledge resources. In Sustainable Development of Human Resources in a Globalization Period; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Rollins, J.; Yan, E. Web of Science use in published research and review paper 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Sci. Metr. 2018, 115, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tukker, A. Product service for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 7, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Davison, I.; Adams, R.; Edordu, A.; Picton, A. A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med. Educ. Rev. 2019, 53, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.S.; Moeinzadeh, S.; Tseng, M.L.; Tan, K. A literature review on environmental concerns in logistics: Trends and future challenges. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 24, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchet, G.; Melacini, M.; Perotti, S. Environmental sustainability in logistics and freight transportation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 775–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Durst, S. Knowledge management in environmental sustainability practices of third-party logistics service providers. Vine 2015, 45, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, P.L.; Iranmanesh, M.; Kumar, K.M.; Foroughi, B. The impact of multinational corporations’ socially responsible supplier development practices on their corporate reputation and financial performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaiser, F.H.; Ahmed, K.; Sykora, M.; Choudhary, A.; Simpson, M. Decision support systems for sustainable logistics: A review and bibliometric analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1376–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, S.; Zorzini, M.; Cagno, E.; Micheli, G.J.L. Green supply chain practices and company performance: The case of 3PLs in Italy. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 640–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S. Participation in global value chain and green technology progress: Evidence from big data of Chinese enterprises. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 1648–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baah, C.; Opoku-Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Faibil, D.; Abdoulaye, F.A.M. Examining the correlations between stakeholder pressures, green production practices, firm reputation, environmental and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing SMEs. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 27, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Arora, A.S.; Sivakumar, K.; Burke, G. Strategic sustainable purchasing, environmental collaboration, and organizational sustainability performance: The moderating role of supply base size. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsis, A.M.; Chen, I.J. Do motives matter? Examining the relationships between motives, SSCM practices and TBL performance. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25/3, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huge-brodin, M.; Sweeney, E.; Evangelista, P. Environmental alignment between logistics service providers and shippers—A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020, 31, 575–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P. Environmental sustainability practices in the transport and logistics service industry: An exploratory case study investigation. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 12, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.H. Barriers to low-carbon warehousing and the link to carbon abatement: A case from emerging Asia. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Colicchia, C.; Creazza, A. Is environmental sustainability a strategic priority for logistics service providers? J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 198, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Nilsson, F. Developing environmentally sustainable logistics: Exploring themes and challenges from a logistics service providers’ perspective. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 46, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacken, J.; Rodrigues, V.S.; Mason, R. Examining CO2e reduction within the German logistics sector. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2014, 25, 54e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Seuring, S. Environmental impacts as buying criteria for third party logistical services. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lammgård, C. Intermodal train services: A business challenge and a measure for decarbonization for logistics service providers. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2012, 5, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, J.; Figliozzi, M.; Faulin, J. Assessment of the carbon footprint reductions of tricycle logistics services. Transp. Res. Rec. 2016, 2570, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maas, S.; Schuster, T.; Hartmann, E. Stakeholder pressures, environmental practice adoption and economic performance in the German third-party logistics industry-a contingency perspective. J. Bus. Econ. 2018, 88, 167–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureeyatanapas, P.; Poophiukhok, P.; Pathumnakul, S. Green initiatives for logistics service providers: An investigation of antecedent factors and the contributions to corporate goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.Y.; Tai, A.H.; Zhou, E. Optimizing truckload operations in third-party logistics: A carbon footprint perspective in volatile supply chain. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 63, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudla, N.L.; Klaas-Wissing, T. Sustainability in shipper-logistics service provider relationships: A tentative taxonomy based on agency theory and stimulus-response analysis. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, C.P. 3PL implementing corporate social responsibility in a closed-loop supply chain: A conceptual approach. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 15, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jørsfeldt, L.M.; Hvolby, H.H.; Nguyen, V.T. Implementing environmental sustainability in logistics operations: A case study. Strateg. Outsourcing Int. J. 2016, 9, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, R.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. A multimodal logistics service network design with time windows and environmental concerns. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehmke, J.F.; Campbell, A.M.; Thomas, B.W. Optimizing for total costs in vehicle routing in urban areas. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 116, 242–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulzele, V.; Shankar, R.; Choudhary, D. A model for the selection of transportation modes in the context of sustainable freight transportation. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1764–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicchia, C.; Marchet, G.; Melacini, M.; Perotti, S. Building environmental sustainability: Empirical evidence from Logistics Service Providers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, U.; Huge-Brodin, M. Environmental practices as offerings and requirements on the logistics market. Logist. Res. 2014, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Subramanian, N.; Abdulrahman, M.D.; Zhou, X. Integration of logistics and cloud computing service providers: Cost and green benefits in the Chinese context. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014, 70, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heeswijk, W.J.A.; Mes, M.R.; Schutten, J.M.; Zijm, W.H. Freight consolidation in intermodal networks with reloads. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2018, 30, 452–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karia, N.; Wong, C.Y. The impact of logistics resources on the performance of Malaysian logistics service providers. Prod. Plan. Control. 2013, 24, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caris, A.; Macharis, C.; Janssen, G.K. Planning Problems in Intermodal Freight Transport: Accomplishments and Prospects. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2008, 31, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Low-carbon initiatives of logistics service providers: The perspective of supply chain integration. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, L.; Tao, F.; Wang, S. Multi-depot open vehicle routing problem with time windows based on carbon trading. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laari, S.; Solakivi, T.; Töyli, J.; Ojala, L. Performance outcomes of environmental collaboration. Balt. J. Manag. 2016, 11, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Santoro, L.; Hallikas, J.; Kähkönen, A.K.; Lintukangas, K. Greening logistics outsourcing: Reasons, actions and influencing factors. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2019, 34, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Tang, L. The relationship among green human capital, green logistics practices, green competitiveness, social performance and financial performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 1377–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Werff, E.V.D.; Lurvink, J. The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Towards a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossoni, L.; Poli, I.T.; Sinay, M.C.F.; Araujo, G.A. Materiality of sustainable practices and the institutional logics of adoption: A comparative study of chemical road transportation companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, H.B.; Nordfjaern, T.; Jørgensen, S.H.; Rundmo, T. The value-belief-norm theory, personal norms and sustainable travel mode choice in urban areas. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B. Identifying critical success factors to facilitate reusable plastic packaging towards sustainable supply chain management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Alum, E.; Ahenkorah, E. Exploring financial performance and green logistics management practices: Examining the mediating influences of market, environmental and social performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Source | Review Year | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning problems in intermodal freight transport: accomplishments and prospects | [21] | 1990–2005 | Intermodal freight transport: strategic, tactical, operational planning decisions and solution methods. |

| Environmental sustainability in logistics and freight transportation: A literature review and research agenda | [19] | 1994–2011 | Logistics and freight transportation: sustainability initiatives, factors of its adoption, adoption benefits, barriers to adoption, and the evaluation and measurement of environmental initiatives. |

| Knowledge management in environmental sustainability practices of third-party logistics service providers | [20] | 2000–2014 | 3PLs’ environmental sustainability: green initiatives and influencing factors, energy efficiency in road freight transport companies, buyer’s perspective and collaboration, knowledge management in sustainability. |

| The Physical Internet–review, analysis and future research agenda | [9] | 2011–2017 | Physical Internet based on four factors: organizational readiness, external pressure, perceived benefits, and adoption for sustainable, interoperable, and collaborative freight transport. |

| The role of environmental sustainability in the freight transport mode choice | [10] | 1970–2010 | Role of environmental sustainability and intermodal transport in transport mode decisions within the EU. |

| Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: Systematic literature review and research directions | [11] | 1960–2014 | Logistics service providers (LSPs): green initiatives, the relationship between green initiatives and performance, factors influencing their adoption, customer perspective in the sustainable supply chain, ICTs supporting green initiatives. |

| Decision support systems for sustainable logistics: a review and bibliometric analysis | [22] | 1994–2015 | Decision support systems for sustainable logistics: key themes of identified literature. |

| A literature review on environmental concerns in logistics: trends and future challenges | [18] | 2009–2018 | Review and presents a generic conceptual model for understanding the implementation process of environmental practices in logistics: reverse logistics, closed-loop logistics, green logistics, and environmental logistics. |

| Dimensions of Organizational Design | Environmental Practices | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mission and Vision | A firm vision for sustainability and thereby incorporates the strategies such as Go Green, Go Help, and Go Teach. Incorporated the environmental principles in their mission statement. Incorporated Green logistics principles into the company strategy and operation. Strategy promoting the use of cleaner transport modes and more environmentally friendly vehicles. | [7,31,32,33] |

| Structure and formal system | Formal efforts toward environmental sustainability. Formal environmental policy or strategy. Environmental management system for assessing, monitoring, and reporting on the environmental impacts:

| [34,35,36,37,38] |

| Organizational process and culture | Knowledge and awareness or education and training about ethical and environmental operations. Resource optimization: transport and warehouse capacity. Preservation | [7,31,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Competitive strategy | Environmental sustainability as a source of competitive advantage Intermodality—Transport of goods by multiple modes of transportation. Intra-organizational environmental practices. Cooperation between the LSPs, customers, and other stakeholders. Coordination—managing the interdependencies between the activities of the business functions within a company and between the companies. | [7,31,35,37,41,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| Technology competency | Technology or software for facilitating environmental sustainability and energy efficiency. Modern vehicles cause fewer emissions. Electric and low carbon emitting vehicles. More efficient diesel engines, automatic transmission vehicles, and natural gas–powered units to company fleets. Technology capability: Intelligent vehicle technologies: this category includes several advanced vehicles or accessories used in transport for reducing adverse environmental impact. Warehouse technologies: this category includes several advanced instruments, machinery, or accessories used in the warehouse for reducing adverse environmental impact IT, accessories, and green software: this category includes several green information and software systems. Generic energy-efficient technology, equipment, and accessories: this category includes energy-efficient technology, equipment, and accessories that use commonly in the facilities of LSPs. | [7,42,52,53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noorliza, K. Determinants of an Environmentally Sustainable Model for Competitiveness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021444

Noorliza K. Determinants of an Environmentally Sustainable Model for Competitiveness. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021444

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoorliza, K. 2023. "Determinants of an Environmentally Sustainable Model for Competitiveness" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021444