2.1. Development of Conceptual Framework

The proposed conceptual framework aims to empirically examine the factors that relate to Greek customers’ perceptions of green supply chains in the electronics industry (and therefore their perception of green electronic products) and explores whether green supply chains influence customers’ purchasing behavior.

The factors incorporated in this framework were first identified through an extensive literature review; these were then discussed with five experts in the field (SCM executives) using an electronic focus group method. The final nine factors selected are:

Customers’ perceptions of electronic products from green supply chains (customers’ perceptions).

Environmental commitment of customers (environmental commitment).

Environmental concerns (environmental concern).

Attitude towards green electronic products.

Perceived environmental knowledge.

Perceived customer effectiveness.

Purchase intention.

Willingness to pay.

Green consumerism and green purchasing behavior.

In the following section, an attempt will be made to conceptualize the aforementioned research factors by referencing various articles in the international literature.

Customer perception of green electronics refers to how individuals perceive and interpret various aspects of such a product based on their sensory experiences, beliefs, social background, and past experiences. According to Roberts [

36], the most reliable indicator of environmentally responsible behavior (i.e., purchasing green products) was found to be consumers’ belief and confidence in their ability to address environmental challenges. This factor is influenced, indicatively, by the quality, price, brand reputation, and design of green electronic products (Ajzen, [

17]).

The environmental commitment of customers reflects their willingness to make choices and take actions that align with environmentally friendly values, including eco-friendly purchases, recycling, conserving energy and resources, and so forth (Hojnik et al. [

33]). Additionally, according to Sohn et al. [

37]), customer commitment constitutes an integral aspect of cohesion and sequential obligations among pertinent stakeholders. Its primary objective is maintained through the relationship linked to a specific service or product, which establishes the pivotal factors that influence the intention to maintain or terminate an economic relationship.

The environmental concern of a customer refers to the level of awareness and worry that an individual has about environmental issues. It reflects a person’s interest in environmental issues such as global warming, pollution, and habitat destruction (Prakash and Pathak, [

38]). Pro-environmental consumer behaviors are significantly influenced by their important role; specifically, it is widely acknowledged as a significant determinant of consumers’ motivation to embrace a sustainable way of life (De Canio et al. [

39]. Further, Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibanez [

40] confirmed the influence of environmental concerns on consumers’ intentions to purchase green energy brands. Thus, environmental concern is typically considered the key element in green marketing research that studies the eco-behavior of customers (Naz et al. [

34]).

Naz et al. [

34] state that, as per Ajzen [

17], “a customer’s attitude is described as an unfavorable or favorable evaluation of a person of a particular behavior”. In other words, the term “attitude toward a behavior” pertains to an individual’s assessment, either favorable or negative, of a certain conduct. It encompasses an individual’s prominent views concerning the anticipated outcomes associated with engaging in that behavior. Numerous parameters play a role in shaping one’s attitude.

Environmental knowledge refers to a person’s understanding of various aspects of the natural environment, including ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources, and the interrelationships between human activities and the environment. It encompasses a wide range of information and principles pertinent to the natural world and the ways in which human actions affect it (Naz et al. [

34]; Tan, [

41]). In this framework, Brosdahl and Carpenter [

42] found that these individuals exhibit a willingness to engage in the purchase of products that are designed to minimize their negative impact on the environment. Additionally, according to some researchers (Levine and Strube, [

43]; Ogbeide et al. [

44]), there exists a considerable relationship between general ecological knowledge and pro-environmental actions, and individuals who possess a greater understanding of long-term environmental issues are more inclined to allocate a larger portion of their financial resources to the acquisition of ecologically sustainable items.

Customer-perceived efficacy commonly refers to an individual’s belief that he/she can contribute to resolving environmental issues and mitigating his/her adversarial effects on ecosystems (Naz et al. [

34]; Tan, [

41]). The self-efficacy belief of customers has a significant influence on their cognitive responses to purchasing product or service decision-making. In other words, this statement suggests that an individual’s sense of self-efficacy has a role in shaping their sense of responsibility and their willingness to engage in environmentally responsible behaviors.

Green purchase intention, also known as eco-purchase intention, refers to a customer’s expressed willingness to buy products that are environmentally friendly and have a lower negative impact in comparison to conventional ones (Lai and Cheng, [

45]; Jaiswal and Kant, [

15]). According to Zhuang et al. [

46], “Purchasing intention is usually defined as a prerequisite for stimulating and pushing consumers to actually purchase products and services… and green purchase intention is the possibility of consumers wishing to purchase environmentally friendly products”.

The willingness to pay provides a vital link in transforming green-minded intentions into tangible actions that promote sustainable consumption. Finally, the green customerism factor broadly refers to green customer behavior, that is, the purchasing of eco-friendly products or services.

2.2. Formulation of Research Hypotheses

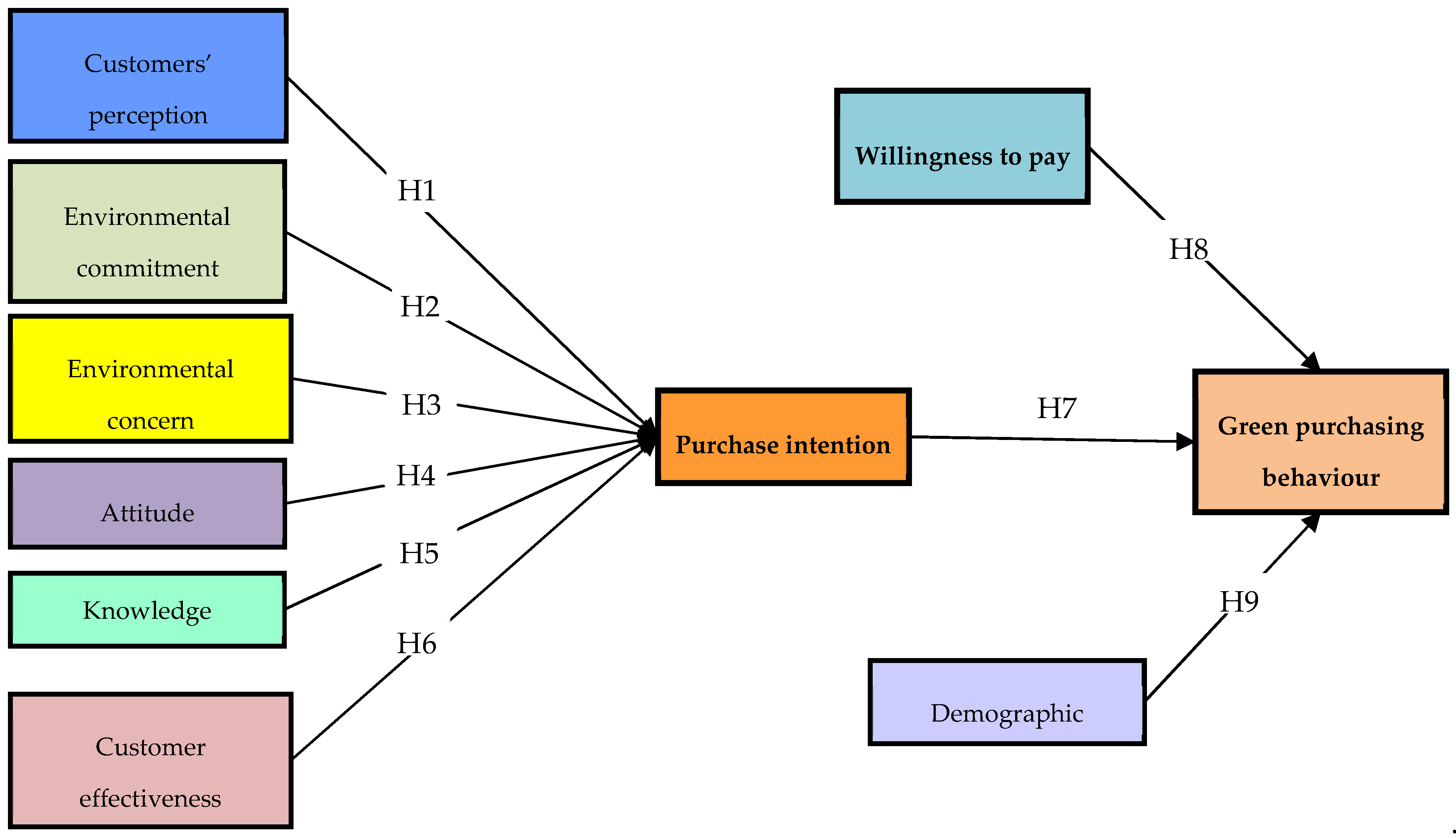

This section presents the research hypotheses that emerged from the research factors mentioned above, as well as the rationale by which they were formulated. The resulting, and novel, research model comprises nine hypotheses that form a two-level hierarchical structure.

Six factors are assumed by the model to positively and significantly impact the green purchase intention of electronics customers. The latter, together with the willingness to pay and the demographic variables, determine the green purchasing behavior of consumers of electronic products. The complete research model is displayed graphically in

Figure 1. In the following section, we discuss the empirical support for the nine research hypotheses that comprise the model.

Based on the findings reported earlier (Hojnik et al. [

33]), it is assumed that customer perception of electronic products from green supply chains will have a significant positive impact on green purchasing intentions. Chen and Chang [

47] and Yu and Lee [

48] confirmed that customer perceptions of green values have a significantly positive effect on purchase intention. Oluwajana et al. [

49] suggested that customers’ environmental commitment has a positive and significant effect on purchasing continuity toward an eco-friendly product.

Overall, previous research (Al Mamun et al. [

50]; Cerri et al. [

51]) established the linkage between customers’ environmental commitment and the intention to procure eco-friendly products, which led to the formulation of research hypothesis 2.

Scholars have documented that a person’s level of environmental awareness has a clear and substantial effect on their attitude to green products, and this, in turn, affects their inclination to buy such items (Yadav and Pathak, [

52]; Paul et al. [

26]). Moreover, Michaelidou et al. [

53] and Fauzan and Azhar [

54] argue that environmental concern is one of the most significant factors that directly affect green purchase intentions. In line with the previous argument, Majeed et al. [

55] found that customers’ environmental concerns have an impact on their purchase intentions. In the same framework, it has also been reported that the high environmental interest of customers is directly associated with a substantial level of intention to purchase these products (Jaiswal and Kant, [

15]; Naz et al. [

34]).

The existing body of research suggests that buyers who hold more positive views about green products tend to be more engaged in the process of deciding to purchase these products (Lee, [

56]; Joshi and Rahman, [

16]). Furthermore, Liao et al. [

57] found that there is a statistically significant and positive impact of customer attitudes on green purchase intention. Consequently, this research aims to study the connections between attitudes toward green products and the intention to purchase them (Jaiswal and Kant, [

15]).

The perceived environmental knowledge factor can be defined as an individual’s cognitive capacity to comprehend issues concerning the environment or sustainability, particularly in areas like air, water, and soil pollution, energy usage, waste generation, and their impact on both society and the natural world (Tan, [

41]; Yadav and Pathak, [

52]). This subjective measure of perceived environmental knowledge was examined by Jaiswal and Kant [

15] to explore the role of attitude towards green products and green purchase intention. The recent research by Elbarky et al. [

58] found that there is no significant correlation between perceived environmental knowledge and green purchase intention; however, they stated that further research incorporating other moderators and mediating factors has to be undertaken.

Within the realm of research on eco-conscious customer behavior, many scholars have extensively examined customers’ sense of effectiveness (Tan, [

41]; Kim, [

59]; Dagher and Itani, [

60]). According to Majeed et al. [

61], “Given the limited studies on the direct impact of customer’s self-efficacy belief on personal norms, and drawing on the above, it is clear that customers’ self-efficacy belief influences customer personal norms in protecting the natural environment” (i.e., purchasing green services and products). Additionally, some academic studies have indicated that the perceived effectiveness of such efforts is closely linked to, and impacts, their decisions to purchase these products (Tan, [

41]; Kang et al. [

62]).

The inclination of an individual to buy environmentally friendly products is referred to as their green purchase intention. Levine and Strube [

43] conducted research aimed at understanding how green purchase intention affects the eco-conscious buying behavior of undergraduate students and the study’s findings revealed a strong and significant correlation between intentions and the purchasing behavior of the subjects; consequently, customers tended to exhibit more extensive eco-friendly buying behaviors (Naz et al. [

34]).

According to Le Gall-Ely [

63] “Willingness to pay or reservation price, defined as the maximum price a given consumer accepts to pay for a product or service, is of particular interest as it is richer in individual information”. Additionally, willingness to pay represents the highest amount a customer is prepared to spend in order to acquire a specific environmentally friendly product (Li and Meshkova, [

64]). Numerous research studies have investigated customers’ readiness to incur extra expenses to acquire products with a minimal impact on the environment. Scholars have documented that customers are open to paying an additional cost if they are assured that this contributes to environmental protection (Moser, [

65]; Hinnen et al. [

66]; Naz et al. [

34]).

Several studies have been conducted to assess green purchasing behavior in relation to social and demographic variables (Prakash and Pathak, [

38]; Chekima et al. [

67]). It has been reported that parameters such as age, gender, and educational level are paramount to understanding customers’ green purchasing behavior (Naz et al. [

34]). As a result of this analysis, we derived the following nine hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Customers’ perceptions of green electronic products have a positive and significant impact on their intention to purchase electronics from green supply chains.

Hypothesis 2. The environmental commitment of customers has a positive and significant impact on the intention to buy green electronic products.

Hypothesis 3. The stronger the environmental concern, the stronger the intention of customers to purchase green electronic products.

Hypothesis 4. Attitudes towards green electronic products have a positive and significant impact on the intention to purchase such products.

Hypothesis 5. Perceived environmental knowledge has a positive and significant impact on the intention to purchase green electronic products.

Hypothesis 6. The stronger the perceived efficiency of customers, the stronger the purchase intention of electronic products that originate from green supply chains.

Hypothesis 7. The stronger the green purchase intention, the stronger the customers’ green purchasing behavior toward electronic products.

Hypothesis 8. The stronger the willingness to pay, the stronger the customers’ green purchasing behavior toward electronic products.

Hypothesis 9. Demographic variables positively and significantly impact the customers’ green purchasing behavior toward electronic products.

2.3. Research Methodology

The population targeted by this survey comprises residents of Greece, regardless of gender, age, or educational level. In short, the only limitation for participation in this research was that the participants had to be exclusively resident in Greece, otherwise, it was not possible to proceed to the next step.

Due to the fact that the survey questionnaire was distributed exclusively electronically via Google Forms, it is reasonable to conclude that it was targeted at Internet users only. The questionnaire was distributed in various ways, all of them electronic. This was primarily conducted via email, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Messenger, and posted as a link on some websites. It is clear, therefore, that the sampling approach adopted is the “convenience” and the “snowball” approach since researchers could not control those who viewed and filled in the questionnaire. Each of the nine factors was measured using multiple questions. These variables were derived from relevant international studies and were measured using a five-point Likert scale (i.e., from 1—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree).

The questionnaire consists of four main sections. In the first section, participants are asked about their demographic characteristics, i.e., age, gender, level of education, and place of residency. In the second section are questions about six factors that influence customers’ perceptions and purchasing preferences. The third section includes questions related to the two factors of intention to buy green products and the willingness to pay for such products. Finally, the fourth section includes questions about the dependent factor, green purchasing behavior.

The scales used to measure the factors incorporated in the proposed research model were adopted from various sources, including Jaiswal and Kant [

15], Chaudhary and Bisai [

35], Prakash and Pathak [

38], Tan [

41], Hojnik et al. [

33], and Naz et al. [

34]. A total of 45 closed-ended questions were used to measure all the research factors. Since these scales were in English, they were initially translated into Greek and then back-translated (by a different person) into English to ensure that there was no problem with the translated scales.

Before the full-scale distribution of the questionnaire used in the present survey, the necessary validity check was carried out to ensure that its content and purpose would be easily and fully understood by the majority of the participants.

A pilot application of the questionnaire was conducted in a group of 10 people to identify any ambiguities in its content or general problems of understanding or formulation of the terms used. In addition to this, in-depth discussions were held with students and professionals on the content of the questionnaire to check whether the content of the questionnaire, as a whole, was understandable.

Closed-ended questions with answers on a five-point Likert scale were chosen to simplify the way in which the participant was asked to complete the questionnaire and to make the analysis of the data easier. The total number of questions was 45.

The sample initially included 152 people (n = 152); however, 5 of these people were excluded because they declared themselves to be foreign residents and thus did not proceed to the subsequent stages of the questionnaire. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 147 people, i.e., n = 147. After the above procedures, the necessary corrections were made to the structure of the questionnaire, as well as to its wording and content, so that it could be easily understood by the participants.

All this was absolutely necessary because the factors and their variables were derived from a large number of articles found in the international literature and for this reason, it was necessary to ensure full understanding by the Greek population and successful adaptation to the Greek realities.

Of the individuals who constituted the sample, 48.7% and 51.3% were male and female, respectively. Regarding the ages of the participants, 27.6% were between 26 and 30 years old, 24.3% belonged to the 31–35-year-old age group, and 15.1% were between 21 and 25 years old. All other age groups in the sample constituted substantially lower percentages. Finally, 36.2%, 31.6%, 9.9%, and 9.9% of the survey participants held postgraduate, university, technological institution, and high school degrees, respectively.

Explanatory factor analysis (EFA) was used to unveil underlying patterns in the set of observed variables. Before diving into EFA, preliminary tests like Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin measure were used to assess whether the data were suitable. Bartlett’s test checked whether there were patterns, and KMO assessed sampling adequacy. Eigenvalues revealed how much variance each factor explained, with values above one indicating significance. Factor loadings showed the strength of the relationship between variables and factors. Total variance explained (TVE) gave the cumulative proportion of explained variance. Cronbach’s alpha measured internal consistency reliability. Together, these tests and indices help us understand the underlying structure and reliability of factors identified through EFA.