Sustainability Is Social Complexity: Re-Imagining Education toward a Culture of Unpredictability

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Objectives

Itineraries in Social Complexity and Implications for a Culture of Sustainability

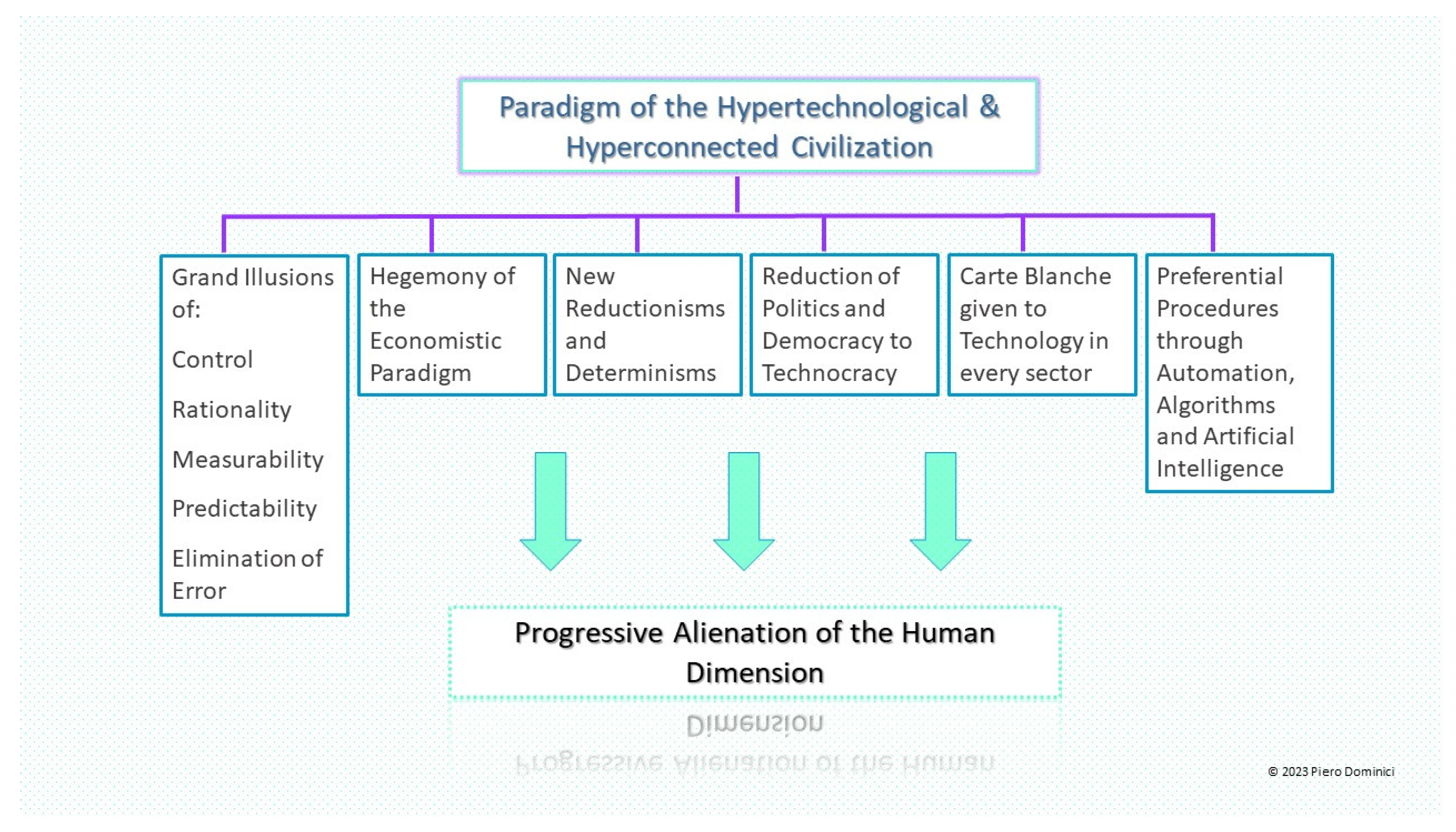

2. The Thought Crisis Standing in the Way of Sustainability and the Progressive Alienation of the Human Dimension

3. The Tyranny of Concreteness in the Society-Mechanism of Simulation and Automation

4. Speed vs. Thought

Reflection and Social Bonds in an Accelerated Age

5. Education Is Innovation, Education Is Inclusion, Education Is Sustainability, Education Is Democracy

6. An Epistemology of Error

Blueprint for a New Approach to Education

7. Sustainability, Equality, Unpredictability

Beyond an Economistic Vision of Society

8. Epilogue

Co-Creating Sustainable Societies

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumann, Z. The Art of Life; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, G.H. Mind, Self and Society; It trans: Mente, Sè e Società; Barbera: Firenze, Italy, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, W. Science and Complexity. Am. Sci. 1948, 36, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. The Human Use of Human Beings; Stati Uniti, Avon Books, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science; Prometheus Books: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Architecture of Complexity. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1962, 106, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. The Computer and the Brain; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- von Neumann, J. The Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, E.N. The Essence of Chaos; Univ. of Wash Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Canguilhelm, G. Le Normal et le Pathologique; It trans, Il normale e il patologico; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, F.E. Systems Thinking. Harmondsworth: Penguin. In What Algorithms Want. Imagination in the Age of Computing; Finn, E., Ed.; It trans, Che cosa vogliono gli algoritmi. L’immaginazione nell’era dei computer; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. More is Different. Science 1972, 177, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature. A Necessary Unity; Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Le Paradigme Perdu: La Nature Humaine; Le Seuil: Paris, France, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. La Méthode; Éditions Points: Paris, France, 1977; Volumes I–VI. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Introduction à la Pensèe Complexe; It trans: Introduzione al pensiero complesso; Sperling & Kupfer: Milano, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Tao of Physics; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life; Random House South Africa: Parklands, South Africa, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals: Forms, Chance and Dimensions; WH Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Le Moigne, J.-L. La Théorie du Système Général; Presses Universitaires: Paris, France, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. La Nouvelle Alliance; Gallimard: Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. Order out of Caos; Bentham Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature; New York Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition; Reidel Publishing Company: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. The Tree of Knowledge; New Science Library: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. La Fin des Certitudes; Editions Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- von Foerster, H. Observing Systems; Intersystems: Seaside, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, S.A. Gene Regulation Networks. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1971, 6, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, S.A. Origins of Order; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziale Systeme; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. The autopoiesis of social systems. J. Sociocybern. 1990, 6, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziologie des Risikos; It trans: Sociologia del rischio; Bruno Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi, G.; Ceruti, M. La Sfida Della Complessità; Bruno Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M. The Quark and the Jaguar; Abacus: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M. Complexity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, E. The Systems View of the World: A Holistic Vision for Our Time; Hampton Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yam, Y. Dynamics of Complex Systems; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. Guns, Germs, and Steel. The Fates of Human Societies; It trans, Armi, acciaio e malattie. Breve storia del mondo negli ultimi tredicimila anni; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. Collapse How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed; It trans: Collasso. Come le società scelgono di morire o vivere; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, K.M.; White, M.C.; Long, R.G. Why Study the Complexity Sciences in the Social Sciences? Hum. Relat. 1999, 25, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L. Linked. How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life; Perseus: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G. The Science of Complexity. Epistemological Problems and Perspectives. Sci. Context 2005, 18, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, P. La Comunicazione Nella Società Ipercomplessa; Condividere la conoscenza per governare il mutamento; FrancoAngeli: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. For an Inclusive Innovation. Healing the Fracture between the Human and the Technological. Eur. J. Future Res. 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, P. Dentro la Società Interconnessa. La Cultura Della Complessità per Abitare i Confini e le Tensioni Della Civiltà Ipertecnologica; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. Educating for the Future in the Age of Obsolescence. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing (ICCI*CC), Milan, Italy, 23–25 July 2019; Volume 4, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. The Digital Mockingbird: Anthropological Transformation and the “New Nature”. World Futures. J. New Paradig. Res. 2022, 78, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, P. Beyond the Darkness. The world-system and the urgency of rebuilding a truly open and inclusive civilization, capable of coping with organizational complexity. Riv. Trimest. Sci. Dell’amministrazione 2022, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. Human Hypercomplexity: Error and Unpredictability in Complex Multi-Chaotic Social Systems. In Multi-Chaos, Fractal and Multi-Fractional Artificial Intelligence of Different Complex Systems; Karaca, Y., Baleanu, D., Zhang, Y.-D., Gervasi, O., Moonis, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; ISBN 9780323900324. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. The weak link of democracy and the challenges of educating toward global citizenship. Prospects 2023, 53, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolis, G.; Nicolis, C. Foundations of Complex Systems; World Scientific: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Montuori, A. Journeys in Complexity: Autobiographical Accounts by Leading Systems and Complexity Thinkers; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, P.L. Untangling Complex Systems: A Grand Challenge for Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.R.; Baker, R.M. Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential, Applications for the Social Sciences. Systems 2019, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blastland, M. The Hidden Half. How the World Conceals its Secrets; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- von Hayek, F.A. The Theory of Complex Phenomena. In The Critical Approach to Science and Philosophy; Bunge, M., Ed.; Essay in Honor of K.R.Popper; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Haken, H. Synergetics: An Introduction. Nonequilibrium Phase-Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry and Biology; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. The Self-Organizing Economy; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Poincaré, H. Sur l’équilibre d’une masse fluide animée d’un mouvement de rotation. Acta Math. 1885, 7, 259–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education; It trans, Democrazia e educazione. Un’introduzione alla filosofia dell’educazione; La Nuova Italia: Firenze, Italy, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. La Ricerca Della Certezza; La Nuova Italia: Firenze, Italy, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Come Pensiamo; La Nuova Italia: Firenze, Italy, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Maritain, J. La Persona e il Bene Comune; Morcelliana: Brescia, Italy, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci, A. Quaderni del Carcere (4 voll.); Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1948–1951. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. La Pedagogia Degli Oppressi, Ed; Gruppo Abele: Torino, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Les Sept Savoirs Nécessaires à L’éducation du Futur; It trans, I sette saperi necessari all’educazione del futuro; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. La Tête Bien Faite; It trans: La testa ben fatta. Riforma dell’insegnamento e riforma del pensiero; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, M. Come Educare il Potenziale Umano; Garzanti: Milano, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Profumo, F. Leadership per L’innovazione Nella Scuola; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maffei, L. Elogio Della Ribellione; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sloman, S.; Fernbach, P. The Knowledge Illusion. Why We Never Think Alone; Stati Uniti, Penguin Publishing Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, A. Radical Technologies. The Design of Everyday Life; It trans, Tecnologie radicali. Il progetto della vita quotidiana; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, K. Atlas of AI; It Trans: Né intelligente né artificiale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. Per Un’etica dei New-Media; Firenze Libri Ed.: Firenze, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. Controversies on hypercomplexity and on education. In Controversies in the Contemporary World; Fabris, A., Scarafile, G., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam-Philadelphia, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, T. La Vie Commune. Essai D’anthropologie Générale; It trans, La vita comune.L’uomo è un essere sociale; Pratiche Ed.: Milano, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Touraine, A. Un Nouveau Paradigme. Pour Comprendre le Monde Aujourd’hui; It trans, La globalizzazione e la fine del sociale. Per comprendere il mondo contemporaneo; Il Saggiatore: Milano, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, E. L’individuo Senza Passioni, Individualismo Moderno e Perdita del Legame Sociale; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rainie, L.; Wellman, B. Networked: The New Social Operating System; It trans, Networked. Il nuovo sistema operativo sociale; Guerini: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, J. Gaia. A New Look at Life on Earth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Weltrisikogesellschaft. Auf Der Suche Nach Der Verlorenen Sicherheit; It trans, Conditio Humana.Il rischio nell’età globale; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tegmark, M. Life 3.0. Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, H. Hello World. How to be Human in the Age of the Machine; It trans, Hello World. Essere Umani nell’era delle machine; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M. The Myth of Research-Based Policy and Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre; It trans: Il metodo delle scienze storico-sociali; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, H. Alienation and Acceleration: Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality; NSU Press: Aarhus/Malmö, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. On Democracy; It trans, Sulla democrazia; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone; It trans, Capitale sociale e individualismo. Crisi e rinascita della cultura civica in America; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, C. Coping with Post-Democracy; It trans, Postdemocrazia; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. Understanding Knowledge As a Commons; It trans: La conoscenza come bene comune. Dalla teoria alla pratica; Bruno Mondadori: Milan, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Dopo la Democrazia; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Not for Profit. Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Princeton: Princeton University Press; It trans, Non per profitto. Perché le democrazie hanno bisogno della cultura umanistica; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, C. Il Disagio Della Democrazia; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Canfora, L. La Democrazia. Storia di Un’ideologia; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. Democratic Deficits: Critical Citizens Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. La Società Dell’irresponsabilità; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, T.H. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E.C. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society; It trans, Le basi morali di una società arretrata; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; It trans, Fondamenti di teoria sociale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, R. Citizenship. A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, P. The Struggle for a Society of Responsibility and Transparency: The core question of Education and Culture. In Preventing Corruption through Administrative Measures; Carloni, E., Paoletti, D., European Union Programme Hercule III (2014–2020), European Commission, Eds.; ANAC, Morlacchi Ed.: Perugia, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. The Wealth of Networks. How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom; It trans, La ricchezza della Rete. La produzione sociale trasforma il mercato e aumenta le libertà; Università Bocconi Ed: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Plebe, A.; Emanuele, P. Filosofi Senza Filosofia; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. The Myth of the Framework; Routhledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Nella Spirale Tecnocratica. Un’arringa per la Solidarietà Europea; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lévinas, E. Humanisme de L’autre Homme; It trans Umanesimo dell’altro uomo; Il Melangolo: Genova, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. Das Prinzip Verantwortung, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main; It trans, Il principio responsabilità. Un’etica per la civiltà tecnologica; Einaudi: Torino, Italia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Inequality Reexamined; It trans, La diseguaglianza. Un riesame critico; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Poincaré, J.H. Science et Méthode; Flammarion: Paris, France, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Routhledge: London, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolution; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, I.; Musgrave, A. Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Theorie des Kommunikativen Handelns, Bd.I Handlungsrationalität und Gesellschaftliche Rationalisierung; It trans Teoria dell’agire comunicativo, voll.I, Razionalità nell’azione e razionalizzazione sociale, vol.II, Critica della ragione funzionalistica; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; It trans, Una teoria della giustizia; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, N. Superintelligence. Paths, Dangers, Strategies; It trans, Superintelligenza. Tendenze, pericoli, strategie; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sadin, È. L’Intelligence Artificielle ou L’enjeu du Siècle; It trans, Critica della ragione artificiale. Una difesa dell’umanità; Luiss University Press: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan; It trans, Il cigno nero, come l’improbabile governa la nostra vita; Il Saggiatore: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. Antifragile; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dominici, P. Sustainability Is Social Complexity: Re-Imagining Education toward a Culture of Unpredictability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416719

Dominici P. Sustainability Is Social Complexity: Re-Imagining Education toward a Culture of Unpredictability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416719

Chicago/Turabian StyleDominici, Piero. 2023. "Sustainability Is Social Complexity: Re-Imagining Education toward a Culture of Unpredictability" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416719

APA StyleDominici, P. (2023). Sustainability Is Social Complexity: Re-Imagining Education toward a Culture of Unpredictability. Sustainability, 15(24), 16719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416719