Eco-Friendly Transactions: Exploring Mobile Payment Adoption as a Sustainable Consumer Choice in Taiwan and the Philippines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Mobile Payment

2.2. Hedonic Motivation (HM) and Utilitarian Motivation (UM)

2.3. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

2.3.1. Performance Expectancy (PE)

2.3.2. Effort Expectancy (EE)

2.3.3. Social Influence (SI)

2.3.4. Facilitating Condition (FC)

2.4. Behaviour Intention (BI)

3. Measures and Data

3.1. Measures

3.2. Participants and Sample Profile

4. Results

4.1. Reliability Analysis

4.2. Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity

4.3. Structure Equation Modeling Analysis (SEM)

4.3.1. Model Fit

4.3.2. Path Analysis

4.4. Mediator Effect

4.4.1. Taiwan

4.4.2. The Philippines

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions and Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghezzi, A.; Renga, F.; Balocco, R.; Pescetto, P. Mobile Payment Applications: Offer state of the art in the Italian market. info 2010, 12, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Piercy, N.C.; Williams, M.D. Modeling consumers’ adoption intentions of remote mobile payments in the United Kingdom: Extending UTAUT with innovativeness, risk, and trust. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Thomas, M.; Baptista, G.; Campos, F. Mobile payment: Understanding the determinants of customer adoption and intention to recommend the technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, M.P.; Scarazzato, T.; Munchen, D.D.; Dartora, P.C.; Veit, H.M.; Bernardes, A.M.; Dias, P.R. Eco-friendly electronics—A comprehensive review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2001263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.T.Y.; Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R. Mobile payment technology in hospitality and tourism: A critical review through the lens of demand, supply and policy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3636–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Niu, H. Green consumption: Environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behavior. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, B.H. Digital Detox: Why Taking a Break from Technology Can Improve Your Well-Being; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Özekicioğlu, H.; Yilmaz, B.; Alkan, G.; Oğuz, S.; Kocabaş, C.; Boz, F. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on the electronic product trade of the G-7 countries: A complex network analysis approach and panel data analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujari, A.; Gaggi, O.; Palazzi, C.E. A mobile sensing and visualization platform for environmental data. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2020, 66, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. Smartphones, distraction narratives, and flexible pedagogies: Students’ mobile technology practices in networked writing classrooms. Comput. Compos. 2019, 52, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerviler, G.; Demoulin, N.T.M.; Zidda, P. Adoption of in-store mobile payment: Are perceived risk and convenience the only drivers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Nim, N.; Agarwal, A. Platform-based mobile payments adoption in emerging and developed countries: Role of country-level heterogeneity and network effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1529–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Dai, W.; Liu, D.; Hu, Y. Quality of e-commerce agricultural products and the safety of the ecological environment of the origin based on 5G Internet of Things technology. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, G.W.; Ping, T.A.; Muthuveloo, R. Antecedents of Behavioral Intention to Adopt Internet of Things in the Context of Smart City in Malaysia. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 442–456. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Predicting the determinants of the NFC-enabled mobile credit card acceptance: A neural networks approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 5604–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. The Practice of Management; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Ashfaq, M.; Begum, S.; Ali, A. How “Green” thinking and altruism translate into purchasing intentions for electronics products: The intrinsic-extrinsic motivation mechanism. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessey, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadwallader, S.; Jarvis, C.B.; Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L. Frontline employee motivation to participate in service innovation implementation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Hsu, P.-Y.; Chen, J.; Shiau, W.-L.; Xu, N. Utilitarian and/or hedonic shopping—Consumer motivation to purchase in smart stores. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.B.; Choo, H.J. How virtual reality shopping experience enhances consumer creativity: The mediating role of perceptual curiosity. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.N.; Franz, S.A.; Jarrett, N.L.; Pickett, S.M. Nature enhanced meditation: Effects on mindfulness, connectedness to nature, and pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 864–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Guo, F.; Yu, F.; Liu, S. The effects of online shopping context cues on consumers’ Purchase intention for cross-border e-commerce sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Bastounis, A.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Stewart, C.; Frie, K.; Tudor, K.; Bianchi, F.; Cartwright, E.; Cook, B.; Rayner, M.; et al. The effects of environmental sustainability labels on selection, purchase, and consumption of food and drink products: A systematic review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 891–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Carr, C.L.; Peck, J.; Carson, S. Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Chen, J. What motivates customers to shop in smart shops? The impacts of smart technology and technology readiness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Alzahrani, M. Investigating the Effects of E-Marketing Factors for Agricultural Products on the Emergence of Sustainable Consumer Behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatimah, H.; Susanto, P.; Abdullah, N.L. Hedonic motivation and social influence on behavioral intention of e-money: The role of payment habit as a mediator. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, E.; Florsheim, R. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: The online experience. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.-J. The effects of utilitarian and hedonic online shopping value on consumer preference and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poong, Y.S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Takada, J.-I. Investigating the drivers of mobile learning acceptance among young adults in the World Heritage town of Luang Prabang, Laos. Inf. Dev. 2016, 33, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, K.T.; Mizerski, R. An Exploratory Study of the responses and relationships involved in the evaluation of, and in the intention to purchase new rock music. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Arnold, M.J. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating differential effects on retail outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.-A.; Hlédik, E.; Dabija, D.-C. Predicting consumers’ purchase intention through fast fashion mobile apps: The mediating role of attitude and the moderating role of COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 186, 122111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Zhang, T.; Bilgihan, A. Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zefreh, M.M.; Edries, B.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. Understanding the antecedents of hedonic motivation in autonomous vehicle technology acceptance domain: A cross-country analysis. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Song, Y.; Zhou, P. Continued use intention of travel apps: From the perspective of control and motivation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2022, 34, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Sachan, A. m-Government experience: A qualitative study in India. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 46, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zeng, X. Sustainability of government social media: A multi-analytic approach to predict citizens’ mobile government microblog continuance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Junaid, M.; Zafar, A.U.; Li, Z.; Fan, M. Online purchase intention in Chinese social commerce platforms: Being emotional or rational? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.G. Non-functional motives for online shoppers: Why we click. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, D.N.; Tham, J.; Azam, S.M.F.; Khatibi, A.A. An empirical analysis of perceived transaction convenience, performance expectancy, effort expectancy and behavior intention to mobile payment of Cambodian users. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2019, 11, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; de Luna, I.R.; Montoro-Ríos, F.J. User behaviour in QR mobile payment system: The QR Payment Acceptance Model. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2015, 27, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, N. Consumer attitudes on mobile payment services—Results from a proof of concept test. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2014, 32, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, N.F.A.; Adnan, H.R.; Firmansyah, F.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Kurnia, S.; Purwandari, B. Why do people want to use location-based application for emergency situations? The extension of UTAUT perspectives. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrave, M.; Waeterloos, C.; Ponnet, K. Ready or not for contact tracing? investigating the adoption intention of COVID-19 contact-tracing technology using an extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azawei, A.; Alowayr, A. Predicting the intention to use and hedonic motivation for mobile learning: A comparative study in two Middle Eastern countries. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, G.; Burnaz, S. Finance. Adoption of mobile payment systems: A study on mobile wallets. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 5, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sripalawat, J.; Thongmak, M.; Ngramyarn, A. M-banking in metropolitan Bangkok and a comparison with other countries. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2011, 51, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Miltgen, C.L.; Popovič, A.; Oliveira, T. Determinants of end-user acceptance of biometrics: Integrating the “Big 3” of technology acceptance with privacy context. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Kim, Y.; Hsu, J.; Tan, X. The effects of social influence on user acceptance of online social networks. Int. J. Human–Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. Analysis of online social networks: A cross-national study. Online Inf. Rev. 2010, 34, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roethke, K.; Klumpe, J.; Adam, M.; Benlian, A. Social influence tactics in e-commerce onboarding: The role of social proof and reciprocity in affecting user registrations. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 131, 113268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Are personal innovativeness and social influence critical to continue with mobile commerce? Internet Res. 2014, 24, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, J.; Wu, K.; Huang, X.; Kong, N.; Campy, K.S. Characterizing Chinese consumers’ intention to use live e-commerce shopping. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, K.; Yadav, R. Behavioural intention to adopt mobile wallet: A developing country perspective. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2016, 8, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungilo, G.G.; Setyohadi, D.B. Factors influencing acceptance of online shopping in Tanzania using UTAUT2. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2020, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Chan, F.K.; Thong, J.Y. Designing e-government services: Key service attributes and citizens’ preference structures. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lu, H.; Hou, M.; Cui, K.; Darbandi, M. Customer satisfaction with bank services: The role of cloud services, security, e-learning and service quality. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Zheng, G.; Hamayun, M.; Ibrahim, A.M. The antecedents of willingness to adopt and pay for the iot in the agricultural industry: An application of the UTAUT 2 theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobti, N. Impact of demonetization on diffusion of mobile payment service in India: Antecedents of behavioral intention and adoption using extended UTAUT model. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 472–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimon, M.G.; Bin Yusoff, R.Z.; Mokhtar, S.S.M. The mediating role of hedonic motivation on the relationship between adoption of e-banking and its determinants. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 558–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Paul, J.; Korfiatis, N.; Lytras, M.D. Examining the role of consumer impulsiveness in multiple app usage behavior among mobile shoppers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 140, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Ramli, F.A.A.; Shaw, N. The moderating influence of brand image on consumers’ adoption of QR-code e-wallets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumussoy, C.A.; Calisir, F. Understanding factors affecting e-reverse auction use: An integrative approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, B. An integrative model for understanding the sustainable entrepreneurs’ behavioural intentions: An empirical study of the Italian context. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3519–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.; Huang, Y.; Qian, L.; Song, J. Privacy paradox for location tracking in mobile social networking apps: The perspectives of behavioral reasoning and regulatory focus. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 190, 122412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Zhang, X. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: U.S. vs. China. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lee, B.C.; Ho, S.H. Consumer attitude toward gray market goods. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, G.; Oliveira, T. A weight and a meta-analysis on mobile banking acceptance research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.-T.T.; Ho, J.C. The effects of product-related, personal-related factors and attractiveness of alternatives on consumer adoption of NFC-based mobile payments. Technol. Soc. 2015, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.-B.; Tan, G.W.-H. Mobile technology acceptance model: An investigation using mobile users to explore smartphone credit card. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 59, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurel, B. Computers as Theatre; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Drumwright, M. Engaging consumers and building relationships in social media: How social relatedness influences intrinsic vs. extrinsic consumer motivation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, Y. Will virtual reality be a double-edged sword? Exploring the moderation effects of the expected enjoyment of a destination on travel intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.-J.; Leong, L.-Y.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lee, V.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Mobile social tourism shopping: A dual-stage analysis of a multi-mediation model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Peng, M.Y.-P.; Anser, M.K. Enhancing consumer online purchase intention through gamification in China: Perspective of cognitive evaluation theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechine, H.; Lakhal, S.; Ndjambou, P. A meta-analysis of the UTAUT model: Eleven years later. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. L’administration 2016, 33, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Explaining social media adoption for a business purpose: An application of the UTAUT model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A systematic literature review and theory evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbad, M.M.M. Using the UTAUT model to understand students’ usage of e-learning systems in developing countries. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7205–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.U.; Hameed, Z.; Khan, S.N.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, M.T. Exploring the effects of culture on acceptance of online banking: A comparative study of pakistan and turkey by using the extended UTAUT model. J. Internet Commer. 2022, 21, 183–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Alalwan, A.A.; Shammout, A.B.; Al-Badi, A. An analysis of the factors affecting mobile commerce adoption in developing countries: Towards an integrated model. Review of International Business and Strategy 2019, 29, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G. Shopping motives, big five factors, and the hedonic/utilitarian shopping value: An integration and factorial study. Innov. Mark. 2006, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, D.W. Validating Instruments in MIS Research. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados; Bookman Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P. Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.L.; Bool, N.C.; Chiu, C.L. Challenges and factors influencing initial trust and behavioral intention to use mobile banking services in the Philippines. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 246–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.J.R.; Sharma, D.K.B.; Petalio, J. Losing Kapwa: Colonial legacies and the Filipino American family. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2017, 8, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayli, S. The impact of digital banking on customer satisfaction in the Lebanese banking industry: The mediating effect of user experience. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Sci. 2023, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Simintiras, A.C.; Yeniaras, V.; Oney, E.; Bahia, T.K. Redefining confidence for consumer behavior research. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct Variable | Taiwan | Philippines | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s α | VIF | Cronbach’s α | VIF | |

| PE (Performance Expectancy) | 0.937 | 2.928 | 0.878 | 2.898 |

| EE (Effort Expectancy) | 0.959 | 2.906 | 0.905 | 3.030 |

| SI (Social Influence) | 0.868 | 1.191 | 0.811 | 1.575 |

| FC (Facility Condition) | 0.849 | 1.965 | 0.865 | 2.625 |

| UM (Utilitarian Motivation) | 0.936 | 3.752 | 0.874 | 1.876 |

| HM (Hedonic Motivation) | 0.937 | 2.165 | 0.874 | 1.817 |

| BI (Behavior Intention) | 0.951 | 0.920 | ||

| Total | 0.966 | 0.948 | ||

| Panel A: Convergent Validity Analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Items | Taiwan | Philippines | |||||

| FC | CR | AVE | FC | CR | AVE | |||

| UM | 7 | 0.705–0.879 | 0.945 | 0.713 | 0.711–0.854 | 0.910 | 0.591 | |

| HM | 3 | 0.899–0.933 | 0.941 | 0.841 | 0.771–0.860 | 0.868 | 0.688 | |

| PE | 4 | 0.864–0.926 | 0.932 | 0.792 | 0.834–0.886 | 0.914 | 0.727 | |

| EE | 4 | 0.907–0.922 | 0.960 | 0.857 | 0.784–0.898 | 0.915 | 0.729 | |

| SI | 5 | 0.678–0.839 | 0.873 | 0.581 | 0.701–0.824 | 0.886 | 0.610 | |

| FC | 3 | 0.715–0.903 | 0.856 | 0.667 | 0.838–0.896 | 0.893 | 0.736 | |

| BI | 5 | 0.774–0.853 | 0.921 | 0.702 | 0.870–0.937 | 0.951 | 0.797 | |

| Panel B: Discriminant validity analysis | ||||||||

| Panel B1: The case of Taiwan | ||||||||

| AVE | UM | HM | PE | EE | SI | FC | BI | |

| UM | 0.713 | 0.844 | ||||||

| HM | 0.841 | 0.798 | 0.917 | |||||

| PE | 0.792 | 0.499 | 0.625 | 0.89 | ||||

| EE | 0.857 | 0.531 | 0.665 | 0.416 | 0.926 | |||

| SI | 0.581 | 0.455 | 0.570 | 0.357 | 0.379 | 0.762 | ||

| FC | 0.667 | 0.555 | 0.696 | 0.435 | 0.463 | 0.397 | 0.817 | |

| BI | 0.797 | 0.555 | 0.695 | 0.589 | 0.538 | 0.430 | 0.543 | 0.893 |

| Panel B2: The case of the Philippines | ||||||||

| AVE | UM | HM | PE | EE | SI | FC | BI | |

| UM | 0.591 | 0.769 | ||||||

| HM | 0.688 | 0.637 | 0.829 | |||||

| PE | 0.727 | 0.376 | 0.590 | 0.853 | ||||

| EE | 0.729 | 0.427 | 0.671 | 0.396 | 0.854 | |||

| SI | 0.610 | 0.378 | 0.593 | 0.350 | 0.398 | 0.781 | ||

| FC | 0.736 | 0.465 | 0.730 | 0.431 | 0.490 | 0.433 | 0.858 | |

| BI | 0.702 | 0.412 | 0.646 | 0.387 | 0.540 | 0.635 | 0.478 | 0.838 |

| Panel A: Taiwan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV | IV | Std. (β) | S.E. | p-Value | R2 |

| HM | UM | 0.798 | 0.057 | 0.000 | 0.636 |

| PE | HM | 0.625 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.391 |

| EE | HM | 0.665 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.443 |

| SI | HM | 0.570 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.325 |

| FC | HM | 0.696 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.484 |

| BI | PE | 0.253 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.541 |

| EE | 0.135 | 0.052 | 0.010 | ||

| SI | 0.050 | 0.058 | 0.259 | ||

| FC | 0.115 | 0.052 | 0.043 | ||

| HM | 0.339 | 0.064 | 0.000 | ||

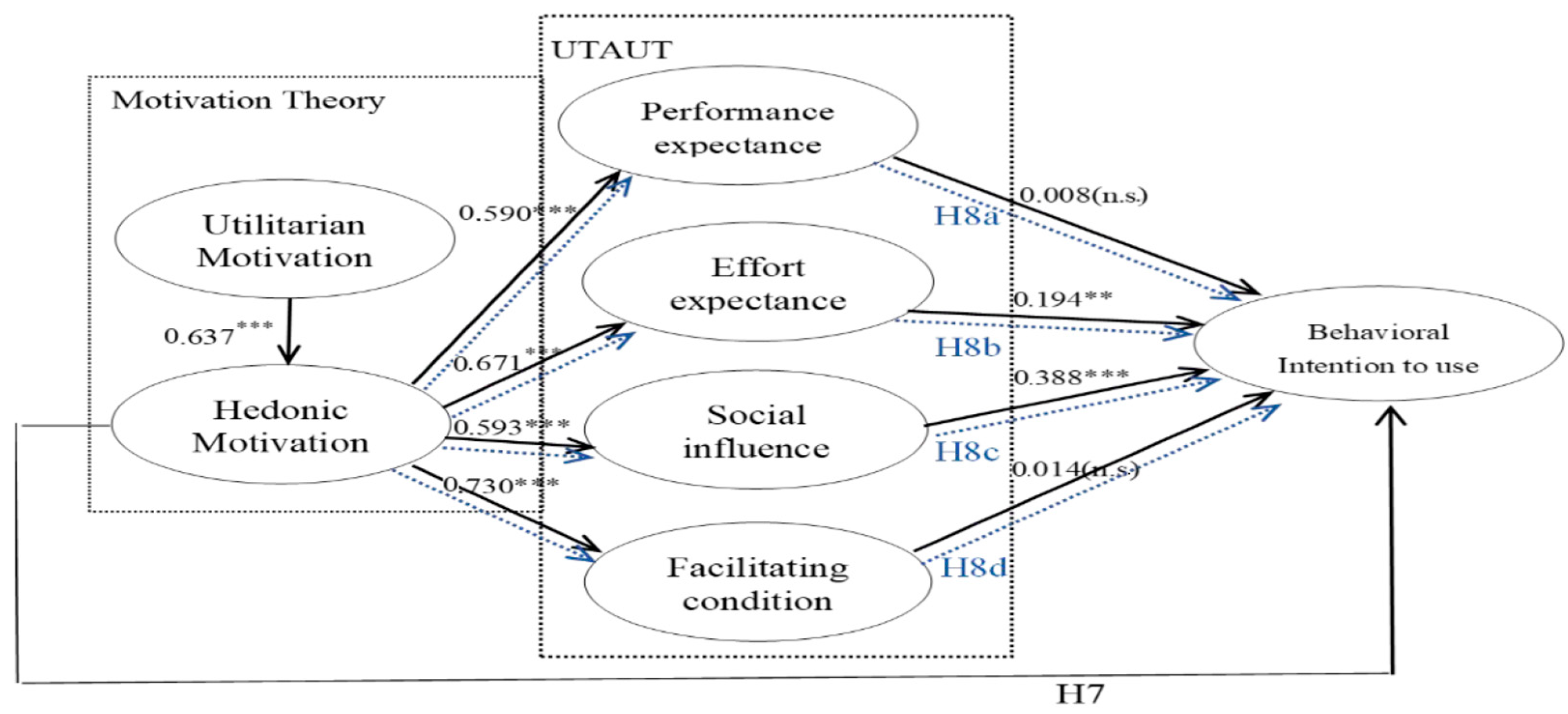

| Panel B: the Philippines | |||||

| DV | IV | Std. (β) | S.E. | p-Value | R2 |

| HM | UM | 0.637 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.406 |

| PE | HM | 0.590 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.349 |

| EE | HM | 0.671 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.450 |

| SI | HM | 0.593 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.352 |

| FC | HM | 0.730 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.533 |

| BI | PE | 0.008 | 0.052 | 0.897 | 0.536 |

| EE | 0.194 | 0.059 | 0.006 | ||

| SI | 0.388 | 0.081 | 0.000 | ||

| FC | 0.014 | 0.065 | 0.867 | ||

| HM | 0.271 | 0.117 | 0.014 | ||

| Panel C: Ranking of factors adopted | |||||

| Factors | Taiwan Std. (β) | Ranking | Philippines Std. (β) | Ranking | |

| HM | 0.798 | 1 | 0.637 | 3 | |

| PE | 0.625 | 4 | 0.590 | 5 | |

| EE | 0.665 | 3 | 0.671 | 2 | |

| SI | 0.570 | 5 | 0.593 | 4 | |

| FC | 0.696 | 2 | 0.730 | 1 | |

| Panel A: Mediator Effect Analysis for Taiwan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | Du = 1000 | ||||

| 95% CI | ||||||

| Std.Err. | Z | p | llci | ulci | ||

| Total Effect | ||||||

| HM→BI | 0.673 | 0.063 | 10.705 | 0.000 | 0.567 | 0.817 |

| Total Indirect Effect | ||||||

| HM→PE→EE→SI→FC→BI | 0.344 | 0.070 | 4.933 | 0.000 | 0.209 | 0.480 |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| HM→PE→BI | 0.153 | 0.041 | 3.718 | 0.000 | 0.071 | 0.233 |

| HM→EE→BI | 0.087 | 0.043 | 2.002 | 0.045 | 0.009 | 0.181 |

| HM→SI→BI | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.878 | 0.380 | −0.033 | 0.090 |

| HM→FC→BI | 0.077 | 0.046 | 1.690 | 0.091 | −0.007 | 0.175 |

| Panel B: Mediator effect analysis for the Philippines | ||||||

| Total Effect | ||||||

| HM→BI | 0.686 | 0.101 | 6.784 | 0.000 | 0.521 | 0.929 |

| Total Indirect Effect | ||||||

| HM→PE→EE→SI→FC→BI | 0.398 | 0.215 | 1.854 | 0.064 | −0.101 | 0.774 |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| HM→PE→BI | 0.005 | 0.079 | 0.063 | 0.950 | −0.134 | 0.194 |

| HM→EE→BI | 0.138 | 0.096 | 1.438 | 0.150 | −0.040 | 0.358 |

| HM→SI→BI | 0.244 | 0.063 | 3.863 | 0.000 | 0.146 | 0.383 |

| HM→FC→BI | 0.011 | 0.151 | 0.070 | 0.944 | −0.214 | 0.291 |

| Panel C: Results of mediation effect between Taiwan and the Philippines | ||||||

| Hypothesis | Mediation | Result of Taiwan | Result of Philippines | |||

| H8a | HM→PE→BI | v | x | |||

| H8b | HM→EE→BI | v | x | |||

| H8c | HM→SI→BI | x | v | |||

| H8d | HM→FC→BI | x | x | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, H.-J.; Hung, F.-H.S.; Lee, P.-C.; Ni, Y.; Chen, Y. Eco-Friendly Transactions: Exploring Mobile Payment Adoption as a Sustainable Consumer Choice in Taiwan and the Philippines. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16739. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416739

Niu H-J, Hung F-HS, Lee P-C, Ni Y, Chen Y. Eco-Friendly Transactions: Exploring Mobile Payment Adoption as a Sustainable Consumer Choice in Taiwan and the Philippines. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16739. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416739

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Han-Jen, Fei-Hsu Sun Hung, Po-Ching Lee, Yensen Ni, and Yuhsin Chen. 2023. "Eco-Friendly Transactions: Exploring Mobile Payment Adoption as a Sustainable Consumer Choice in Taiwan and the Philippines" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16739. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416739