1. Introduction

From the pre-Columbian era to Portuguese colonization in the territory that would later become Brazil, the extraction of useful parts of plants was the first activity practiced by humans to meet survival needs [

1]. Extractivism has become one of the most prominent issues in the discourse and movement of forest protection in Latin American and world politics in the last decade [

2].

Extractivism, as a human activity, is characterized by numerous interconnections and is part of a set of actions carried out in the context of socioeconomic, agronomic, and environmental productive activities [

3]. It is a complex of practices, mentalities, power differentials, and the rationalization of socioecological modes of organization [

4].

Extractivism is a model or paradigm of development in which the economies of the Global South are structured to depend predominantly on the exploitation of nature and satisfy the consumption of the Global North [

2,

5]. Extractive activities include any form of resource extraction, cultural appropriation, emotional extraction, human exploitation, and a technocapitalist world system [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Forest products are extracted by traditional people groups and communities, who commonly explore the diversity of natural products for subsistence [

11]. Extractivism is a complex and dynamic system consisting of an activity that occurs in a landscape independent of its domestication stage [

12]. By this logic, from the colonial period to the contemporary era, several extractive products have had, and continue to have, great importance in the economic, social, and political formation of the Amazon—specifically, the “drugs of outback,” including, the cacao (

Theobroma cacao L.), rubber tree (

Hevea brasiliensis M. Arg.), Brazilian chestnut tree (

Bertholletia excelsa H.B.K), palm heart, and the fruit of

açaizeiro (

Euterpe oleracea Mart.)—and the extraction of wood, turtle oil, pirarucu, mining, oil, and hydropower [

13].

The sustainability of extraction changes with technological progress, the emergence of economic alternatives, population growth, reduction of inventories, the wage levels of the economy, and fluctuations in relative prices, among other factors [

14]. The defenders and supporters of extractivism should value the people who carry out the activity by providing structural and legal support as well as connecting them with market opportunities [

15].

Similarly, farmers in the Amazon are not averse to innovation, provided they have markets, profits, increased agricultural productivity, the ability to domesticate potential plants, replacement for export (internal and external) of tropical products (rubber, palm oil, cocoa, rice, milk, poultry, eggs, vegetables, and so on), and recovery of areas that should not have been deforested [

16]. Moreover, the management and domestication practices of crops or rearing should be developed and even evolve toward the discovery of synthetics (synthetic rubber, artificial juices, synthetic vanilla, plastic wood, and industrial yarns) [

17].

These productivity dynamics and attention to markets are not yet present in extractive reserves (RESEXs), which are areas of high biodiversity that allow for the sustainable relationship of local communities with natural resources. After the assassination of Chico Mendes (1988), RESEXs have been applied to proposals or projects that predominantly defend the preservation of forest resources. However, extractivism can be feasible only in reduced market situations, because in market growth, farmers are encouraged to expand their plantations, being converted into an model new of economic transformation [

18,

19].

Currently, defenders and extractivist activists argue that RESEXs represent an ideal conservation and development model to reduce deforestation and ensure the preservation of biological diversity. Without this, reserve residents will not have a market to ensure family subsistence.

The ambiguity of 21st century extractivism reflects the lack of consensus on its role in the success or failure of the activity [

20]. The extractive economy is a cycle that starts with the expansion phase, then stabilizes, and finally declines. The Amazon rainforest is vulnerable to climate change and anthropogenic actions, such as deforestation and burning, and both of these factors affect natural and environmental resources [

21].

Although plant extraction has been a good strategy for the breeding and permanence of farmers in the field, price fluctuations in markets and the socioeconomic vulnerability of family farmers are persistent challenges [

22]. Extractive activity alone cannot reduce poverty or promote the monetary income of more than 256,000 properties in the Amazon [

23,

24].

Therefore, several important questions arise: What has been happening with the extractive economy of rubber, Brazilian nuts, and vegetable oils in RESEXs? Are financial values derived from extractive activities capable of ensuring subsistence for families and curbing deforestation? From this perspective, this study evaluates whether the supply of extractive products transformed into economic value can ensure the subsistence of families and contain deforestation.

In this sense, although the extraction of rubber, chestnuts, and vegetable oils presents sustainability from the agricultural, forestry, and ecological point of view, low returns, low productivity of land, and lack of labor point to weak economic viability of plant extraction in RESEXs.

This study is comprised of five sections. In

Section 2, we present the materials and methods, particularly the research subjects, study design, specific procedures, and data analysis. In

Section 3, we present the results of the primary data and analysis. In

Section 4, we discuss the results based on the identified situations. Finally, in

Section 5, we present our conclusions and recommendations based on this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

This study was conducted at RESEXs Alto Juruá, Rio Ouro Preto, and Rio Cajari during two periods: January to March 2017 and January to March 2019. A total of 384 interviews were conducted—234 in 2017 and 150 in 2019—at homes, with the primary decision-maker as the only respondent.

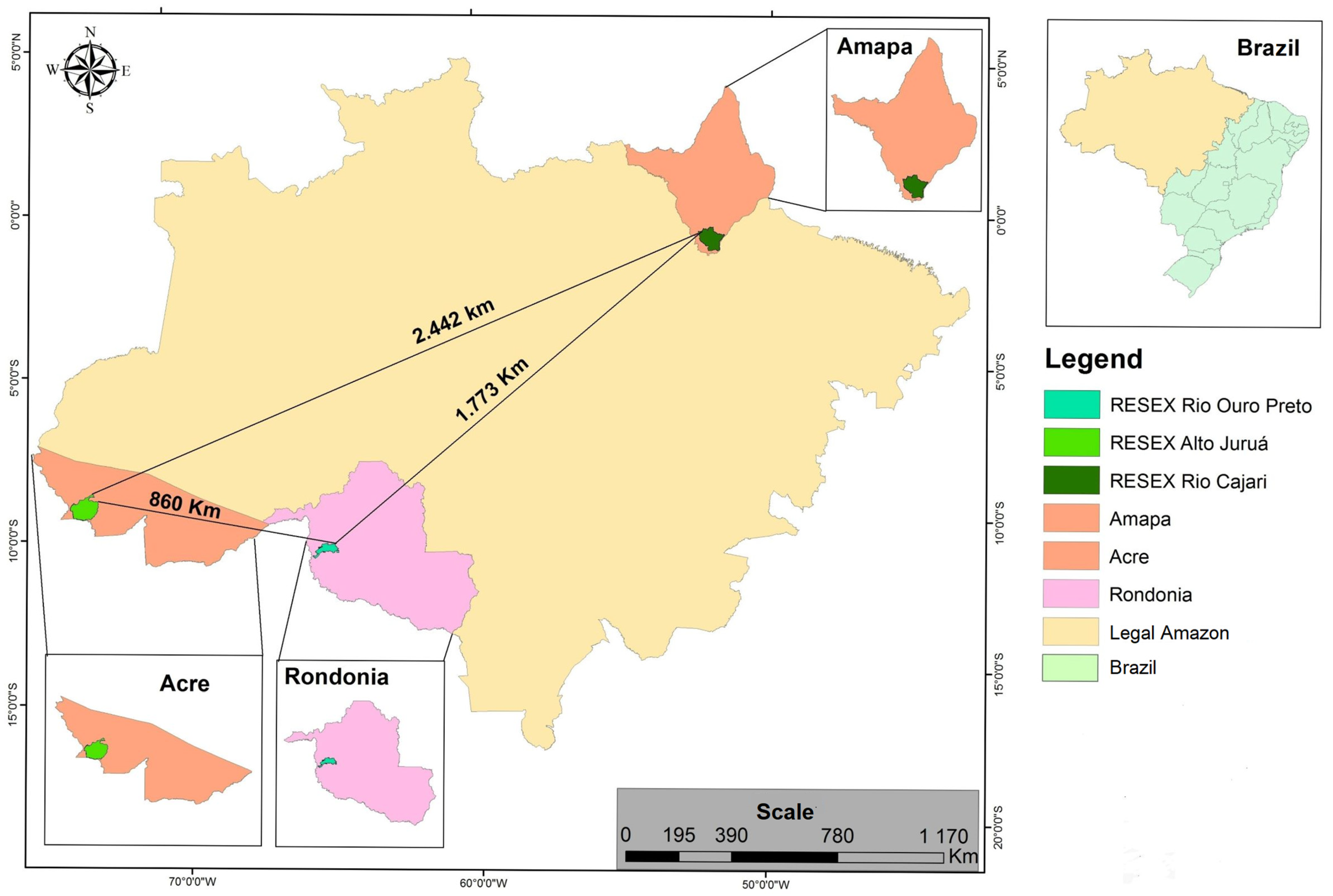

Figure 1 shows a map of the identification points and distances between RESEXs.

RESEX Alto Juruá was created through Decree 98,863, with 537,946 ha on 23 January 1990. According to the last demographic census, RESEX is located in the municipality of Marechal Thaumaturgo (Acre), where 4170 inhabitants (1042 families) live, divided into 80 communities, on the banks of the Juruá, Tejo, Breu, and Manteiga Rivers [

25]. The main products with economic potential are cassava flour, tobacco, brown sugar, beans, rice, corn, sweet potatoes, cattle breeding, sheep, pigs, and poultry.

RESEX Rio Ouro Preto was created through Decree 99,166, with 204,631 ha on 13 March 1990. According to the last demographic census, RESEX is located in the municipalities of Guajará-Mirim and Nova Mamoré (Rondônia), with 699 inhabitants (175 families) distributed across 12 communities along the vicinal roads of Pompeu, Tapper, Ramal dos Macacos, and Rio Ouro Preto [

25]. The main products with economic potential are Brazilian nuts, cassava flour, cattle, bananas, beans, rice, corn, poultry, and pigs.

RESEX Rio Cajari was created through Decree 99,145, with 532,397 ha on 12 March 1990. Based on the last population census, the RESEX is located in the municipalities of Laranjal, Mazagão, and Vitória do Jari (Amapá), with 2293 inhabitants (573 families) divided into 31 communities along the vicinal roads, BR-156, and Rio Cajari [

25]. The main products with economic potential are Brazilian nuts, cassava flour, beans, rice, corn, potatoes, and cattle.

2.2. Study Delineation

The association method with interference was the most appropriate approach to accomplish the objective of the study because of the dependence identified among the variables of the environmental, economic, institutional, and social groups [

26,

27]. For example, extractivism depends on investments in technologies for collection, beneficiation, and processing; however, in the absence of implementation, productive activity remains stagnant, with no prospective growth (environmental group). This situation affects the income of the family unit (economic group) and the subsistence of thousands of families (social group) owing to the ineffectiveness of public policies (institutional group).

Deforestation is the main reference for assessing the sustainability or unsustainability of RESEXs. The advancement of deforestation indicates that public policies fail or do not correspond to the interests of local communities. In this sense, the causal relationship and direct dependence between the variables of the environmental, economic, social, and institutional groups is evident.

The association method was carefully employed to clearly and objectively respond to the objectives of the study. Therefore, there was concern about the interconnection of each section of the manuscript to contribute to both the article and area of study. The strategy used was to understand the literature, evidence, phenomena, and groups of variables based on the primary and secondary collections.

2.3. Procedures

The RESEXs Alto Juruá, Rio Ouro Preto, and Rio Cajari were chosen for this study, because they have potential for environmental conservation and socioeconomic development, partly because of their 32 years of existence and wealth of environmental, economic, institutional, and social information. In addition, RESEXs have 7152 inhabitants (1790 families) distributed across 113 communities. We chose a simple random sample through sample calculation, because this meets the methodological criteria and demographic questions of the RESEXs. Relevance levels were 95% and 5.4%, respectively.

where

is the sample size (384 interviewees),

is the universe size (7152 locations),

is the proportion found (50%),

is the confidence level (95%), and

is the margin of error (5%).

The procedures for defining the sample followed those of traditional research, specifically a significance level of 95% and a sampling error of 5%. However, we entered the RESEXs only after approval of the research project submitted to the Biodiversity Authorization and Information System of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation.

The criteria for choosing communities were based on a list of all the communities in each RESEX. We conducted a draw, and the communities were selected as follows: for RESEX Alto Juruá: Tartaruga I, Tartaruga II, Pau Brasil, Foz do Piranha, Arenal, Fazenda Cachoeira, Belforte, Adão e Eva, São Luiz, Bandeirante I, Bandeirante II, Pedra Alta, São José, Bethânia, Tapuã, Acuriá I, Acuriá II, Jardim da Palma, and Matrinchã e Foz do Tejo; for Ouro Preto River: Alfredo Carneiro, Tapper, Pompeu, Nova Aliança, Bom Jesus, Três José, Ouro Preto, Floresta, and Nossa Senhora do Seringueiro; and for Cajari River: Açaizal, Água Branca do Cajari, Ariramba, Boca do Braço, Conceição do Mariacá, Dona Maria, Mazagão, Mangueiro, Marinho, Martins, Poção, Santana, Vila Santana, Santa Clara, Santa Rita, São Luiz, São João Paraíso, São José, São Pedro, São Pedro Ajurixi, Sororoca, Tapereira, and Terra Vermelha.

For data collection, semi-open forms and audio interviews were used when authorized by the interviewees. Due to a lack of accessibility in the Amazonian summer period, the collection occurred in winter, when the rivers flood. Therefore, we used fast river transport to access the communities, because most of them are located in the riverside regions of RESEXs. For the communities along the roads, pickup trucks with 4 × 4 traction suitable for obstacles and poorly maintained vicinal roads were used.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were collected after defining the qualitative criteria and included occasional voice recordings, informal conversations, and interviews (accompanied by questionnaire forms). Information from this procedure has become indispensable for understanding the relationship between traditional communities and natural resources, their simple ways of life, environmental and socioeconomic conditions, and institutional relations.

Qualitative criteria were added to the quantitative criteria, specifically during data treatment. Descriptive statistical analysis of frequency allowed for tests of mean, median, mode, standard deviation, variance, and correlation. Vector data, drainage matrix, locality, and hydrography were analyzed to create a map. The references used for elaboration were the National Water Agency, the management plan or the use of RESEXs, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, and the National Institute of Space Research (INPE/PRODES).

3. Results

Extractivism comprises productive activities involving Brazilian nuts, rubber, and vegetable oils (the main ones being

andiroba,

copaíba,

cumaru, and

muru-muru). These activities have strong socioeconomic importance but have changed over time.

Figure 2 shows the productive conditions for the three activities and the presence of the Bolsa Verde Program in the RESEXs.

Based on the results of the interviews, Brazilian nut collections were conducted between November and February in the RESEXs. Moreover, the product does not impact natural and environmental resources but generates income and contributes to subsistence. However, annual production fluctuates because of the decrease in rainfall and climate change in the Amazon Region. Nevertheless, extractivists continue with the activity because of their cultural and environmental significance, as the nuts are free, and the only associated cost is the labor cost of the family unit.

Once, the rubber cycle (1880–1910) was the main economic activity; however, after this period, the activity declined and could not be revived. The rise of international markets, lack of investments, and the growth of agriculture and livestock have rendered rubber a product of low economic value in RESEXs.

Vegetable oils in RESEXs are used culturally as medicines, subsistence, and for sale, if available, to tourists of interest. It is important to consider that vegetable oils represent the knowledge, customs, and culture of local communities; however, they have low economic value for local inhabitants.

The Bolsa Verde Program was created by Law No. 12,512/2011 and was regulated by Decree No. 7572/2011 with the objective of conserving environmental resources and benefiting traditional peoples and communities. Due to many rules and insufficient resources to serve all of families within the RESEXs, beneficiaries could only withdraw R$ 300.00 every three months. The government was ineffective in environmental conservation and improving the living conditions of local communities, because the institutional discourse prevailed under the implementation of extractive policies.

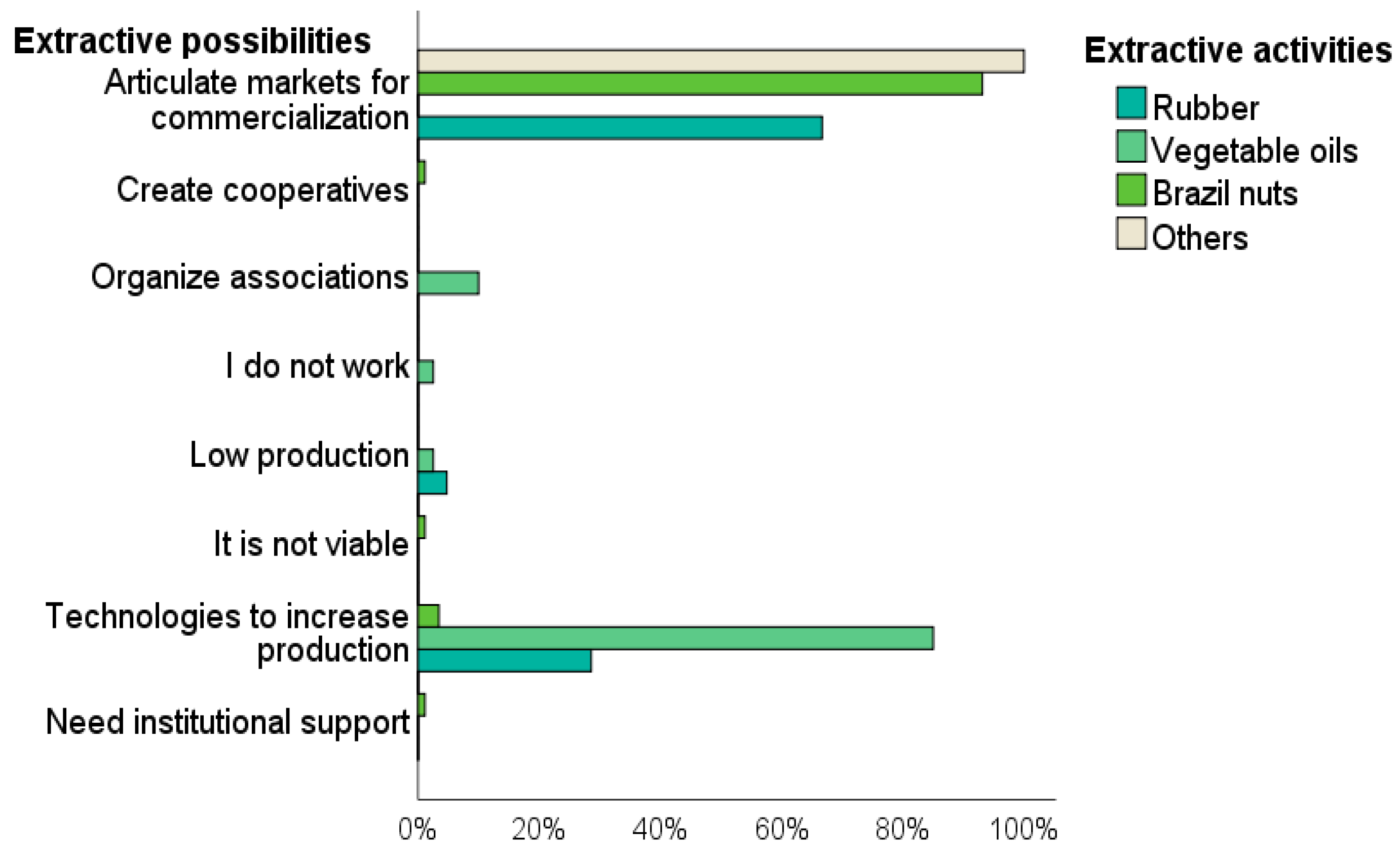

The discourse of activists, scientists, and environmentalists in favor of environmental conservation is increasing worldwide. Extractive activity is among the reasons for creating RESEXs, partly because of its low impact on natural resources and socio-environmental benefits. Three decades after the creation of RESEXs, extractive policies have not achieved the desired results (

Figure 3).

According to respondents, extractive policies correspond to the interests of national and international investors and are less important to extractive communities. Dissatisfaction stems from local inhabitants who have daily contact with natural resources and subsistence needs. This reality is persistently complex, because there is no institutional investment in social and financial capital for the productive activities of local communities.

Monthly household income is an indicator of the economic condition of extractive activities. Thus, it is possible to observe the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of collectors or producers, subsistence conditions, and possible impacts on environmental resources.

Figure 4 shows the monthly household incomes from Brazilian nut, rubber, and vegetable oil extraction.

According to the results of the interviews, monthly household income was below 1/2 minimum wage. This value corresponds to low supply, which fluctuates annually, as well as to low investments in productive activity. At RESEX Alto Juruá, there are few productive chestnut trees

and low incentives to extract vegetable oils and rubber production owing to the strengthening of agriculture and livestock. However, some strategic institutional initiatives should be implemented to reduce the environmental and socioeconomic difficulties and enhance extractive activity. The extraction of rubber, Brazilian nuts, and vegetable oils will advance significantly, based on critical decisions (

Figure 5).

Expansion of the productive activities of extractivism, development of markets, and implementation of technologies for collection and processing are recommended. This measure streamlines the work of the extractive producer, enhances the value of the product in regional and international markets, adds value to the product, and increases family income. However, if there is no change in the extractive policy, livestock and agriculture activities will continue to increase to unsustainable levels—in particular, cattle rearing, which requires extensive land area to create, recreate, and fatten.

Table 1 shows the annual, total accumulation and periods of deforestation.

RESEX Rio Ouro Preto has the lowest population density and less than half the number of hectares in relation to the Alto Juruá and Cajari Rivers; however, it has the highest deforestation rate. At the time of starting, the three RESEXs experienced deforestation, which continuously increased with the persistence and entry of bovine and buffalo producers.

RESEX Alto Juruá has a demographic density and level of deforestation almost twice that of RESEX Rio Cajari due to the culture established after the rubber plantation crisis. As the state did not pay the costs of expropriation to owners with ownership rights after the RESEX creation process, owners continued to explore primary areas to expand bovine productive activity.

RESEX Rio Cajari has the lowest level of deforestation in relation to the RESEXs Alto Juruá and Rio Ouro Preto because of the culture, awareness, and investment in the productivity of extractivism, mainly for Brazilian nuts. For example, on the margin of BR-156, in the Água Branca do Cajari Community in the municipality of Laranjal do Jari, Brazilian nuts and their by-products are commercialized. This region has been transformed into a tourist destination to promote extractive activities.

In general terms, deforestation accumulation fluctuates with each period, mainly due to the influence of cattle markets close to the RESEXs and the absence or low investment in extractive activity.

4. Discussion

We conclude that plant extractivism should not be considered the only development option, as the economic base cannot ensure subsistence for family units in RESEXs. Due to the expansion of markets, extractive activity loses exclusivity, and this is led by low productivity, dispersion in the forest, production collection, processing, economy of scale, and low prices paid by buyers.

For example, latex extraction continues to suffer from price fluctuations and disincentives to activity, although it was previously a good strategy for the production and permanence of extractivists in the Amazonian area [

22]. Moreover, because of the low prices of rubber and vegetable oils, the only active product is Brazilian nuts.

Brazilian nuts, rubber, and vegetable oils have potential, but the absence of innovations, production volumes, and technologies hinders their growth [

28]. Extractivism production is ecologically sustainable; however, under current conditions, it does not meet the requirements of subsistence of local communities and environmental conservation [

29].

Plant extractivism is the most appropriate productive model for forest conservation, but it is not economically sustainable on its own because of the limitations of scale and processing, and low productivity of land, labor, and income [

30]. The crisis of extractivism emanates from the absence of investment, inefficiency of public policies, and institutional management [

31]. This proves that institutional agents have politically correct discourse but do not implement actions that enable productive activity growth.

Additionally, plant and animal extractivism is the reason and cause of regional delay, as it is based on the availability of natural resources and belief in their inexhaustibility [

17]. In practice, low productivity, exhaustion, and secular passivity have led to an extractive crisis in RESEXs [

31]. The income generated from extractivism is too low to ensure the subsistence of the inhabitants, because few families engage in this activity while integrating it with agriculture and livestock [

32].

Each extractive product exhibits a specific behavior with regard to the conditions of productivity, processing, pricing, market, and perishability. For example,

babassu has large stocks, low profitability, and a drop in production due to low compensation for the effort spent on its collection and processing [

33]. Furthermore, the extraction of food products or those with elastic demand is more likely to be domesticated [

34].

Logging is economically viable, which is the reason for the expansion of community forest management in the Amazon, albeit unsuccessful in the medium- and long-term [

35]. Economic confidence in livestock and agriculture made extractivism a source of complementary income either due to low supply or low market prices [

36,

37]. This was confirmed in the field, as local communities prioritized productive activities with greater economic value.

In the process of co-evolution, associated production evolves over time owing to technological changes, pricing, markets, and the evolution of the economy. The diversified production of extractivism, sustainable animal husbandry, and agriculture promote food availability, income generation, and food security [

22].

From this perspective, income generation depends on the development of technologies that create economic alternatives and markets that can co-evolve [

14]. There is no perfect solution to environmental consequences, but it is necessary to use environmentally sustainable technologies and processes such as eco-sustainable business models, renewable energies, and the integration of extractivism with other productive activities [

38,

39]. Alternative benefits have not yet been implemented in order to ensure biological diversity and improve the quality of life of the local communities.

Moreover, the value of the forest for economic use or a green economy depends on the location, which comprises the floristic composition, distance to the market, infrastructure and technology, demand, and cultural norms that influence the viability of land use [

40]. Traditionally, the green economy is characterized by subversion and coercion, as well as sacrificing extractivism, numerous ecosystems, and socioecological qualities, in the name of sustainability, renewability, and energy transition [

41,

42,

43].

It is important to maintain extractive activity, because it presents a large stock value; however, the mere discourse of environmentalists, activists, and institutions is not sufficient to ensure the preservation, conservation, and reduction of deforestation. In the Amazon, more than 12,000 square kilometers of vegetation burned in 2021, impacting fauna, flora, and human health [

44]. Conservation units face high deforestation rates due to human actions such as invasion, pasture opening, and logging [

45,

46].

Deforestation in conservation units in the Amazon is increasing, causing environmental, social, and economic impacts [

47]. Livestock and agriculture are the main drivers of deforestation in CUs [

48]. Tropical deforestation occurs at an accelerated pace, resulting in the intensification of the greenhouse effect and warming of the Earth [

49]. These conclusions reaffirm the institutional commitment to reformulate and implement strategic extractive policies to provide environmental, economic, and social gains.

Therefore, it is essential to consolidate the state’s commitment to promote, protect, respect, and guarantee economic, social, cultural, and environmental rights, considering the principles of equality and progressivity, particularly for those who use extractivism as the main source of subsistence [

50]. Extractivism is far from achieving sustainability, as the only product that guarantees the existence of such activity is the Brazilian nut.

The proposal and approval of the privatization of Eletrobrás has aroused the private sector’s interest in the acquisition of thermal power plants in locations far from the Amazon. Brasil BioFuels acquired 36 thermal plants at an auction, four in Acre (municipalities of Marechal Thaumaturgo, Porto Walter, Santa Rosa do Purus, and Jordão) and 12 in Rondônia (municipalities of Porto Velho, Humaitá, São Francisco do Guaporé, Alta Floresta d’Oeste, and Guajará-Mirim).

The project ensures the planting of palm oil for the generation of electricity in places where the transport of diesel oil is difficult to access, particularly during the dry season in the Amazon summer [

51]. This project may be interesting for RESEXs based in the Amazon, because the planting and extraction of oil from oil palms to produce electricity takes advantage of degraded areas and generates employment and income.

6. Recommendations

As a priority, extractivism should be considered a cultural institution and economic model that can promote sustainability. Therefore, a strategy capable of valuing products derived from extractivism should be developed, and an approximation of the markets that remediate the efforts of forest conservationists should be considered.

To avoid deforestation, increasing productivity and sustainability of agroextractive activities, implementing subsistence crops, rearing livestock and small farm animals, and establishing fish farming should be considered to increase income. Swidden and fish farming may be conducted in secondary or deforested areas, whereas plant extraction should be conducted in primary forested areas.

Future studies will present the integration of productive activities of agriculture, extractivism, and animal husbandry or subsistence agroextractivism to ensure food security, environmental conservation, and sustainable practices for local communities of RESEXs.