Abstract

As brand equity (BE) is a valuable, but intangible, asset of any firm, understanding BE represents a primary task for many organizations. Factors that influence the development of BE are of inordinate academic and practical significance and a source of continuous investigation. While the current literature on social media communication (SMC) and BE provides a wealth of information, our study pioneers the most recent processes of mediation and moderation of electronic word-of-mouth and product involvement (PI) in BE research. Accordingly, the results of this work will likely become one of the key sources of information in sustainable marketing planning and in the development of strategies. To accomplish this goal, we assessed the structural relationships among SMC, electronic word of mouth (e-WOM), PI, and BE. A questionnaire survey was administered concerning consumer brands in China. In this survey, due to the need for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, the questionnaire was distributed and collected via the internet. A total of 369 data sets were analyzed by partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results of our investigation reveal that: (a) social media firm- and user-generated content have a positive impact on e-WOM, (b) social media firm- and user-generated content have a positive impact on BE, (c) e-WOM has a positive impact on BE and serves as an intermediary role between SMC and BE, and (d) PI exerts specific moderating effects between SMC and BE.

1. Introduction

The internet has become the largest source of information in the 21st century, and with the advent of its associated websites has markedly changed global business. SMC represents a group of internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0 [1], with the result that it enables the creation and exchange of user-generated information [2]. Cheung, Pires, and Rosenberger [3] noted that the use of social media to entice customers has recently evolved into a major marketing trend for companies. Sustainability has been integrated with marketing and extended to business and social issues [4]. Therefore, an inseparable connection exists between the concept of BE and SMC in sustainable marketing activities. Social Media (SM) is now widely recognized as an effective tool to reduce misperceptions and rumors about brands and improve BE by providing consumers with a new data-driven paradigm to interact, collaborate and exchange information and content online [5]. To link SMC with BE, marketers should be encouraged to use SM as a channel for brand communication [6]. BE is an important concept initially proposed in the field of marketing in the 1980s [7]. Lemon et al. [8] considered that BE refers to the value of the brand, defined as a customer’s subjective and intangible assessment of the brand, above and beyond its perceived objective value. In marketing decision-making processes, firms with a successfully established BE can be readily distinguished from similar brands, and, as a result, increase their appeal to consumers [9]. However, based on a review of marketing and management literature, we found that only limited research has been conducted as to the means through which SMC specifically affects BE in the social media environment.

First, in the context of online communication for brands, few people consider the direct and indirect impacts of e-WOM reviews on BE. There is a gap between measurements of e-WOM research on SMC and BE. Second, to the best of our knowledge, little is known about the combined impact of applying SMCs on BE for both high-involvement and low-involvement product variables [10]. This highlights the need to examine effective BE building processes and assess the means through which SMCs influence BE. There also exists a need to understand how this influence varies as a function of the level of PI, to facilitate the joint use of these elements. Therefore, the issue of whether product engagement moderates this efficacy was also investigated. In summary, although a limited amount of research exists regarding the relationship between SMC and BE, there remains a lack of comprehensive information on the systematic theoretical framework and conceptual model to explain the means by which SMC affects the dimensions of BE through mediating mechanisms [11]. Therefore, in this study we detail a means through which SMC affects BE via the mediating and moderating mechanisms of electronic word-of-mouth and product engagement. To achieve this goal, we describe the construction and validation of a conceptual model in the context of social identity theory and uses and gratifications theory.

The goal of this study is to expand upon the discussion of BE, conduct an in-depth research assessment of BE and develop a documented proposal for the sustainable social media marketing and development of BE. To verify our research model and hypothesis, we used the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis method. Finally, based on our findings, we present some novel insights, the limitations of our study, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Equity (BE)

In general, based on research focus or research perspectives, BE can be divided into firm-based [12], employee-based [13] or consumer-based brand equities (CBBE) [14]. Our current research focuses on CBBE and therefore is limited to a consideration of consumers’ views. Keller [15] first presented the concept of the CBBE model, which proposed that brand knowledge, as determined by the customer’s memory of a brand image, is a key factor in creating BE. One area that offers the greatest opportunity for further brand impact research is digital development [16]. Consumers of social media are considered to be the primary driver of developing BE [17]. Social media communications provide information and interactions that increase brand and relationship equity [18]. These activities increase consumer perceptions of value, build longer-term relationships, and increase recognition of the brand image. Given that the development of internet technology provides new opportunities for firms to interact with current and potential customers [19], it is necessary to explore the impact of SMC, e-WOM, and PI dimensions on BE.

2.2. Social Media Communication (SMC)

SMC refers to the sharing of content production and communication based on user relationships on the internet. Previous research on SMC has mainly focused on two types: (1) firm-generated content (FGC) also referred to as marketing-generated content (MGC) and (2) user-generated content (UGC), which also includes professional user-generated content (PGC) [20]. As one important consequence of internet development, social media provides new avenues for connecting marketers and consumers through popular platforms (SM: such as TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Bilibili) [21]. Kim and Ko [22] identify five major forces, viz., interaction, entertainment, trendiness, customization, and word-of-mouth, that capture and engage consumers’ perceptions of various marketers’ practices on social media and characterize social media marketing activities [23]. Due to the highly rich contents on social media, which influence the way consumers locate information, evaluate products, and generate product reports, many brands use social media platforms to support brand sustainability [18]. Therefore, companies should view social media platforms as key components for their future messaging strategy and utilize a variety of SM tools to maximize results [24].

2.3. Firm-Generated Content (FGC)

FGC can be considered as a type of SMC, such as Facebook posts, tweets, and YouTube videos, which are posted by brand owners on their brand pages, accounts, or social media channels [25,26]. To paraphrase Goh et al. [27], FGC consists of marketers creating content online with the intention of engaging consumers. As FGC has a stronger ability to meet consumer demand for information, it requires less time and cost for customers to locate and obtain information. Marketers also want to present a positive image of their brand and, given that social media profiles are completely controlled by the seller, they will always transmit positive communications of their content [26]. Aesthetically pleasing and reliable FGC fosters not only consumer brand awareness, but also emotional and behavioral responses that develop favorable brand engagements, trust, and relationships [28]. As a result, it is thought that SMC, as created by firms, represents a very important component of an organization’s advertisement and promotion [29].

2.4. User-Generated Content (UGC)

UGC refers to media content created by the public, including any form of online content that is created, initiated, distributed, and consumed by users [30]. Since UGC is developed by social media users with similar interests, consumers are likely to place a high value on their assessments and ideas [6]. In social media, users engage in information interactions in a decentralized and heterogeneous manner through functions such as like, follow, forward, and post [31]. The purpose of the UGC model is self-expression, and its initiative and creativity are brought into full play [32]. It promotes the development of social media technology and enriches social media information. A unique aspect of UGC is that its content is generated by active users in a non-professional environment and differs substantially from firm marketing. Consumers can freely create advertisements to portray positive and negative views of products and firms [33]. Thus, UGC is an important part of social media marketing, which not only increases the amount of content available to customers, but also the sharing of reliable experiences, which also enhances customer trust. UGC has become a concept for evaluating consumer opinions and establishing effective BE [34]. Therefore, it is crucial to study the impact of UGC as related to BE.

2.5. Electronic Word of Mouth (e-WOM)

E-WOM refers to the electronic exchange of knowledge and information among different consumers after using an identical series of products, services, or brands [35]. Consumers report on their specific experience with a particular product, which then has a certain influence on other consumers. E-WOM is a medium of communication dominated by the consumer in the absence of any influence of markets or firms [36]. With the development and widespread use of the internet, it has become increasingly more convenient for consumers to express their opinions on brand products. As a result, channels for consumers with similar interests in a product or brand to exchange information about the brand have been substantially broadened [37]. UGC and e-WOM are often used interchangeably [38], however, we will continue to delve into the relationship between the two as a means to guide marketers in their efforts to maximize the commercial value of e-WOM.

2.6. Product Involvement (PI)

PI has become one of the most important concepts in consumer research, with the structure of this concept originating from literature in the field of psychology [39]. PI refers to the extent of consumers’ interests and efforts in the purchase of a product [40]. The extent of product participation in the CBBE-building process is examined as a moderator in marketing contexts, but the results are equivocal, necessitating further investigation. The argument is that FGC is effective in building consumers’ positive brand attitude when considering high-involvement products, since consumers are more willing to search for information using the Internet and FGC brand pages. SMC exerts a greater effect on high- versus low-involvement products and brands when it comes to BE. This is because customers more readily use social media to research information when deciding on high-involvement products, such luxury goods, cellphones, and airlines [41]. In contrast, as customers are more inclined to base their judgments on convenience, they are less disposed to do so when choosing low-involvement products or brands, such as those found at supermarkets and groceries [42]. Thus, involvement with a product reflects its perceived relevance to consumers’ inherent needs, values, and interests [3]. In recent years, PI in the social media environment, as a theory for connecting the relationship between brands and consumers, has attracted considerable attention [43]. Therefore, in this study, we employed PI theory to explore the impact of SMC on BE in the social media environment and the moderating effects of PI dimensions on this impact.

2.7. Theoretical Background

Uses and gratifications theory (U&G) and social identity theory (SIT) are not new to BE literature. Followers of social media brands are value conscious, and individual perceived benefits play an important role in driving users’ community engagements. U&G theory provides an explanation for consumer’s attraction to SMC activities to gratify cognitive, social/personal, integrative, and hedonic gratifications or benefits as well as sensory, affective, behavioral, and user experiences [44]. User media satisfaction and consumer experience influences the manner in which individuals use media and brands and their behaviors. Therefore, an understanding of consumers’ experience and satisfaction is critical to influencing BE through SMC. Social identity theory also assumes that people identify themselves with certain social groups to enhance their self-esteem and self-concept. SIT has been used to explain conformity and socialization and group-based bias in peer groups, and also serves as a theoretical paradigm to explain the relationship between customers and brands. A brand can serve as a symbol for a social group, allowing customers to feel a sense of shared identity and belonging with that brand. When brands portray a good brand image and effectively position this image in the minds of consumers, these consumers will tend to show some degree of bias towards such brands [45]. Thus, the association between social identity theory and uses and gratifications theory provides support for examining model relationships, demonstrates the linkage of influencer-consumer engagement behaviors, and may develop brand evangelism that represents sustainable consumer-brand relationships.

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Relationship between SMC and e-WOM

What is certain is that online social media provides consumers and marketers with a platform for publishing and sharing information [46]. Firm marketers present the content created by the firm and introduce the features and services of the firm’s products through novel advertisements and other mechanisms [47]. In turn, users can respond to this FGC utilizing published information, e-WOM, or forwarding. Therefore, any FGC may access and influence many users on social media through e-WOM [48]. Although marketers can initiate e-WOM conversations directed to targeted customers, not all FGCs will exert the same impact on all consumers, with some content achieving a sizeable response, while other content does not [49]. It has been reported that reliable content, when created by online marketers, produces consumer agreement and increased attention to that content or online celebrities; whereas the absence of this reliability results in a failure to continue to view this content [50]. Therefore, creating accurate content represents an essential component in generating a positive customer response [51]. Miller and Lammas [52] reported that UGC not only serves as a communication and marketing channel, but also enhances WOM transmission. When people read and share information on social media, at least some of them aim to gain useful information [53]. Moreover, when consumers search for information about products and services online, they are often attracted to the large amount of user-originated content. The findings of Muda and Hamzah also highlight the positive impact that consumers’ perceived credibility regarding the source of user-originated content exerts on purchase intent and word-of-mouth through attitudes toward user-originated content [11]. These studies are identical in that vast numbers of UGCs and FGCs are found in SMC and high-quality UGCs and FGCs will result in more e-WOMs. Therefore, we propose the following two related hypotheses:

Hypothesis H1a.

FGC exerts positive impacts on e-WOM.

Hypothesis H1b.

UGC exerts positive impacts on e-WOM.

3.2. Relationship between SMC and BE

Marketers always actively display the firm’s brand, either through traditional media or SMC [54].FGC on social media influences consumers’ evaluation of brands [28]. These are often regarded as advertisements and can stimulate consumer brand awareness and brand image. Bruhn et al. [26] proposed that firm-generated SMC wields a positive impact on the four elements of BE, consisting of brand loyalty, awareness, perceived quality, and association. In particular, more vivid, emotional, and interactive enterprise-generated content of a presentation, like a video, can generate greater BE [6]. Social media marketing managers can influence BE by including the brand when considering their customer set and through influencing customer loyalty to the brand [55]. As positive or negative information will affect BE, it is very important to understand the impact of user reviews on BE [26]. According to the findings of Yoo et al. [56], when brand communication evokes a favorable response to related brands, it will have a positive impact on BE. For UGC that is informative and useful, positive emotions (thankful, happy) have a positive impact on BE, while negative emotions (dislike, sad) have a negative impact on BE [6]. In addition, results from previous empirical studies have also shown that UGC has a positive impact on BE [54]. Based on the above information, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H2a.

FGC exerts positive impacts on BE.

Hypothesis H2b.

UGC exerts positive impacts on BE.

3.3. Relationship between e-WOM and BE

User-generated online product reviews and e-WOM, which have proliferated rapidly on the internet, have had significant effects on firms and E-commerce [57,58]. E-WOM determines a consumer’s evaluation of the brand, which represents the brand’s value [22]. Interestingly, approximately 71% of customers would purchase products suggested by their social network [59]. Similarly, according to González-Rodríguez et al. [60], consumers who find e-WOM useful are more likely to use e-WOM for their decision-making processes and generate e-WOM to help other users. Therefore, many fashion brands have adopted a social media-centric approach to increase brand engagement and sales [61]. It has been reported that the opinions of experienced customers wields a significant impact on the behavioral decisions of new customers [62], indicating that a firm’s BE largely depends on a user’s evaluation of the brand’s market performance. Determining the effect of e-WOM on BE has always received considerable attention from researchers and marketers. Here, we propose the following hypothesis based on the firm’s efforts to generate communication and establish relationships with consumers to promote effective word-of-mouth communication:

Hypothesis H3.

e-WOM exerts a positive impact on BE.

3.4. Mediating Role of e-WOM

In this study, a further prediction proposed is that there are indirect effects among these variables. The dissemination of e-WOM has become an important channel for consumer opinions, due to ease of access and expansive audiences which then enables a wide range of information diffusion [63]. With this process, the communication between the communicator and recipient can directly or indirectly change the attitude and behavior of the recipient [64]. Jalilvand and Samiei [65] proposed that e-WOM communication, either directly or indirectly, has a strong impact on consumer behavior, leading to behavioral decisions. After collating these research findings, we propose that e-WOM affords a certain intermediary role between SMC and BE, leading to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H4a.

e-WOM has an intermediary role in the relationship between BE and FGC.

Hypothesis H4b.

e-WOM has an intermediary role in the relationship between BE and UGC.

3.5. Moderating Role of PI

PI is the personal knowledge of the product as determined by consumers’ interests and arousal. PI can be divided into either a high or low level of involvement. High PI is based on quality perception while low PI is more susceptible to emotion [66]. The degree of consumer involvement has a significant impact on consumers’ attitudes towards the product or brand [67]. In this way, results from previous studies indicate that PI factors may exert a moderating effect on the relationship between SMC and BE.

Hypothesis H5.

PI will moderate the relationship between SMC and BE.

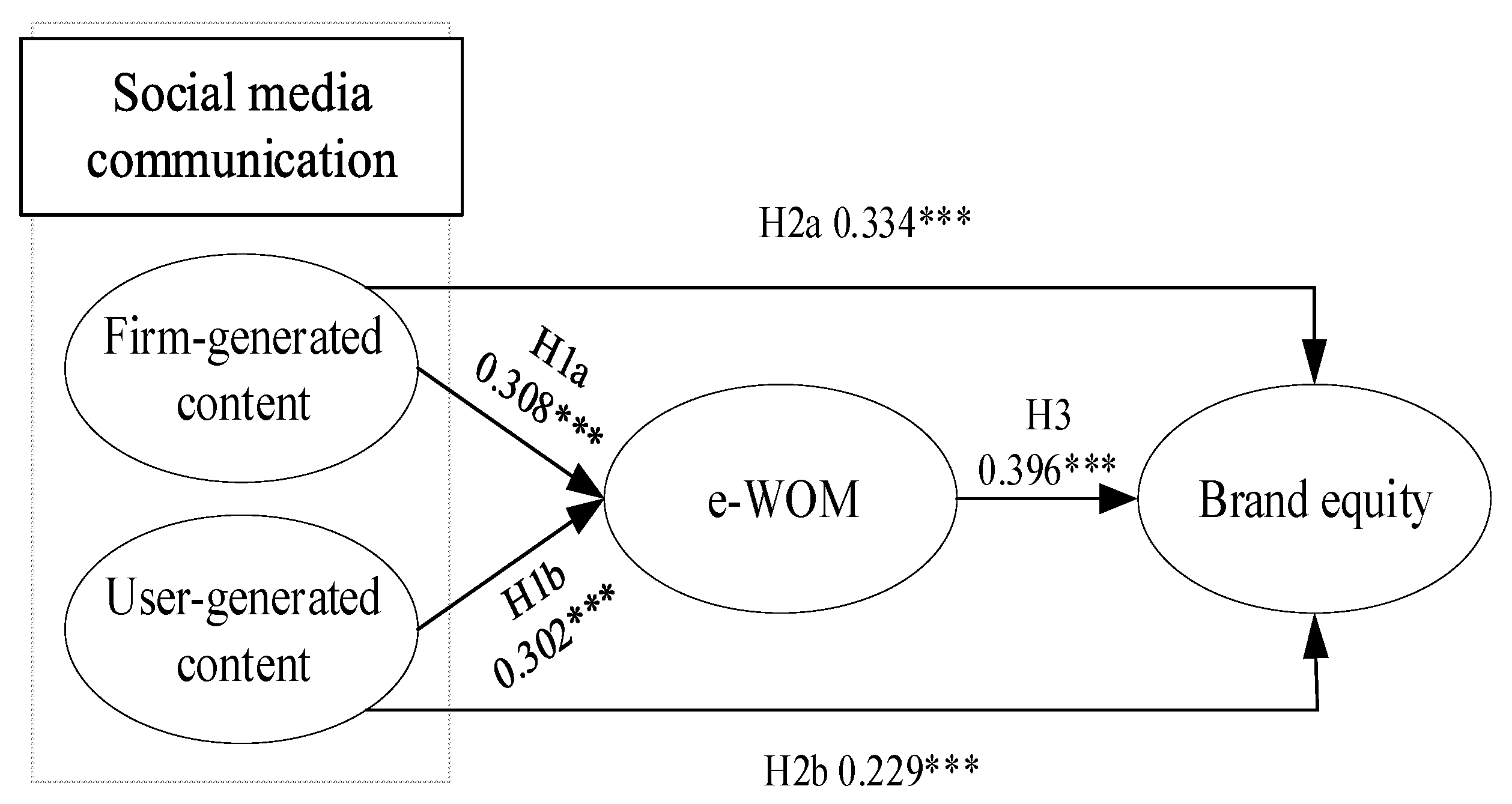

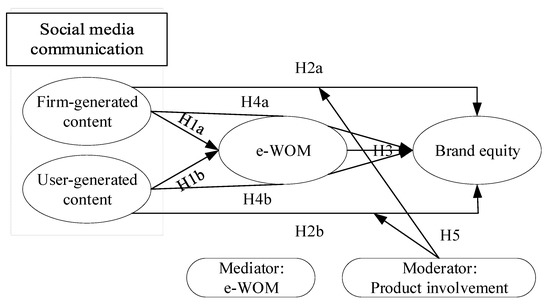

In this study, the conceptual framework was developed according to related research and theories, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Study Design and Methods

4.1. Measurement

Using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 strongly disagree” to “5 strongly agree”, the questionnaire was initially compiled in English and later translated into Chinese by professionals to ensure uniformity and consistency. Finally, 369 valid responses were collected, all from customers in different Chinese regions. To ensure randomness of the sample, a random sampling method was adopted. The original measurement scale is shown in Table 1 and Appendix A.

Table 1.

Measurement items.

4.2. Data Collection

The current study uses quantitative techniques to objectively test the hypothesized associations. In this survey, due to the need for social distancing in the era of COVID-19, the questionnaire was distributed and collected via an internet link (Wenjuanxing, Weixin, Bilibili etc.). WeChat, as one of the most popular social media platforms in China, was used to collect data on market dominance. To reduce social desirability bias and common method variance, an identical Internet Protocol address was established to ensure that data were only submitted once. In addition, we used a “measurement separation procedure” to separate the measurement of predictors (e.g., items related to SMC, e-WOM, and PI were inserted in the initial section of the questionnaire) from the measurement of criterion variables (e.g., items related to BE were inserted in the final section of the questionnaire) [71]. A total of 420 questionnaires were distributed of which 51 were discarded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, data from 369 respondents were used in the data analysis, which represented a final response rate of 87.86%.

4.3. Sample Characteristics

In the final questionnaire, the proportion of men in the sample was slightly greater than that of women (199 versus 170). Respondents were mainly young adults aged 18–29 years (56.10%). Academic qualifications mainly consisted of individuals with junior college and undergraduate levels of education (83.20%). Monthly incomes were in the range of 441–880 USD (57.18%), followed by 881–1310 USD (30.89%). A detailed summary of this information is contained in Table 2. In general, the characteristics of interviewees, such as gender, education level, and monthly income, were consistent with the current demographics of Chinese residents.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of participants’ characteristics.

According to the “Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development” released by the China Internet Information Center, as of June 2022, the number of internet users nationwide was 1.051 billion, with an internet penetration rate of 74.4%. The largest group of internet usage rate is those between 20–39 years of age (37.5%). In addition, millennials tend to conduct more searches and are more influenced by the brand information they retrieve online, as well as by the interactions they experience on social media platforms [44]. The interviewees in this study were between 18 and 38 years old and accounted for a total of 88.89% of the respondents, which provided a representative and realistic sample.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity

An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the data, with the goal of identifying a final set of items with acceptable discrimination and convergence. The first included the Bartlett sphericity and KMO tests for the Bartlett’s sphere test, the chi-square statistic value = 5386.492 with 210 degrees of freedom (df), and a probability value of less than that established for statistical significance (α = 0.05). The KMO value = 0.912, which is greater than the 0.8 required for factor analysis [72]. The factor loading value of the variables was relatively high in all cases (β > 0.7). Cronbach’s α indicator was initially used to measure the reliability of the scales, with 0.7 as the reference value [73]. The results show that all sample variables achieved statistically significant values (α > 0.8), indicating that scale reliability was relatively high. Convergence validity was evaluated by calculating the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extraction (AVE) values. The CR and AVE exceeded the threshold used as a reference at levels of 0.7 and 0.5 [74], respectively, as well as for other indicators of overall fit for the confirmatory factor analysis [75], the values of RFI, NFI, CFI, TLR, IFI, RMSEA, and χ2 were all achieved statistically significant levels (see Table 3). In addition, according to Fornell and Larcker’s [76] discriminant validity test, the square root of AVE of any latent variable should be greater than the correlation between this particular latent variable and other latent variables. Results of this analysis, as contained in Table 4, show that the square root of the AVE is greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations. Thus, the model constructs demonstrate sufficient discriminant validity (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Convergent validity and internal consistency reliability.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

In this study, common method bias was procedurally controlled by acquiring anonymous measurements and reversing some items. The data collected were tested for common method bias using Harman’s single-factor test [77]. Results of the unrotated exploratory factor analysis extracted a total of five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the maximum factor variance explained was 38.553% (less than 40%), indicating that no serious common method bias was present in this study [71].

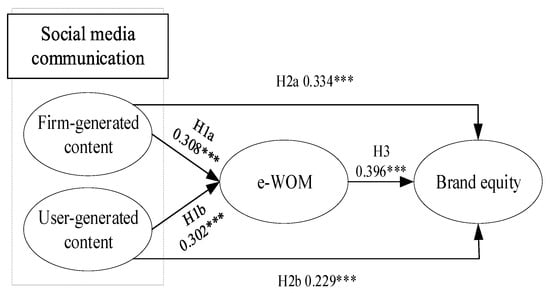

5.2. Tests of Research Hypotheses: Direct Relationships

After evaluating the reliability and validity of the measurement scales, structural equation modeling (SEM) was then employed to test the research hypotheses in the research model and hypothesis development. The SEM is specified by 2 structural relationships depicted by 5 path estimates linking the relationships between the two constructs identified in the proposed model. The results yield an adequate level of fit with χ2 = 112.818, df = 84, CMIN/DF = 1.343, GFI = 0.959, RFI = 0.961, NFI = 0.968, CFI = 0.992, TLR = 0.990, IFI = 0.992, and RMSEA = 0.031. With regard to the impact of SMC upon FGC and UGC in e-WOM (H1a, H1b), both FGC and UGC demonstrated significant direct positive effects on e-WOM, with path coefficients being 0.308 (p = 0.001) and 0.302 (p = 0.000), respectively. In the two paths regarding impacts of FGC and UGC on BE (H2a, H2b), we found that both FGC and UGC showed significant positive direct impacts on BE, with path coefficients being 0.334 (p = 0.000) and 0.229 (p = 0.000), respectively. Therefore, the results of the study provide support for the hypotheses H1a, b and H2a, b. Our results also show that e-WOM had a significant positive impact on BE (β = 0.396) at p-value = 0.000 level, so the assumption held by H3 is also substantiated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research model results. Note: *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

5.3. Tests of Research Hypotheses: Indirect Relationships (Mediating Effect of e-WOM)

A mediating effects analysis was performed to evaluate the mediating effects as previously predicted in this report. Based on the Model 4 mediation model compiled by Hayes [78] the mediation effect of e-WOM upon the relationship between SMC and BE was tested. H4a and H4b proposed that e-WOM exerts an intermediary effect on the relationship between FGC/UGC and BE. Bootstrapping procedures were used to test mediation effects [79]. It can be seen from Table 5 that this situation exists for our H4a (confidence interval = [0.0672, 0.1558]) and H4b (confidence interval = [0.0725, 0.1630]), the confidence interval did not straddle a zero in between. In other words, the mediating role of e-WOM is statistically significant, indicating that SMC not only directly predicts the BE but also predicts the BE of through the mediating effects of e-WOM. In our H4a hypothesis, the direct (0.3098) and intermediary (0.1080) effects account for 74.15% and 25.85% of the total effect (0.4178), respectively. In our H4b hypothesis, the direct (0.2620) and intermediary (0.1152) effects account for 69.46% and 30.54% of the total effect (0.3772), respectively.

Table 5.

Mediating effects of e-WOM.

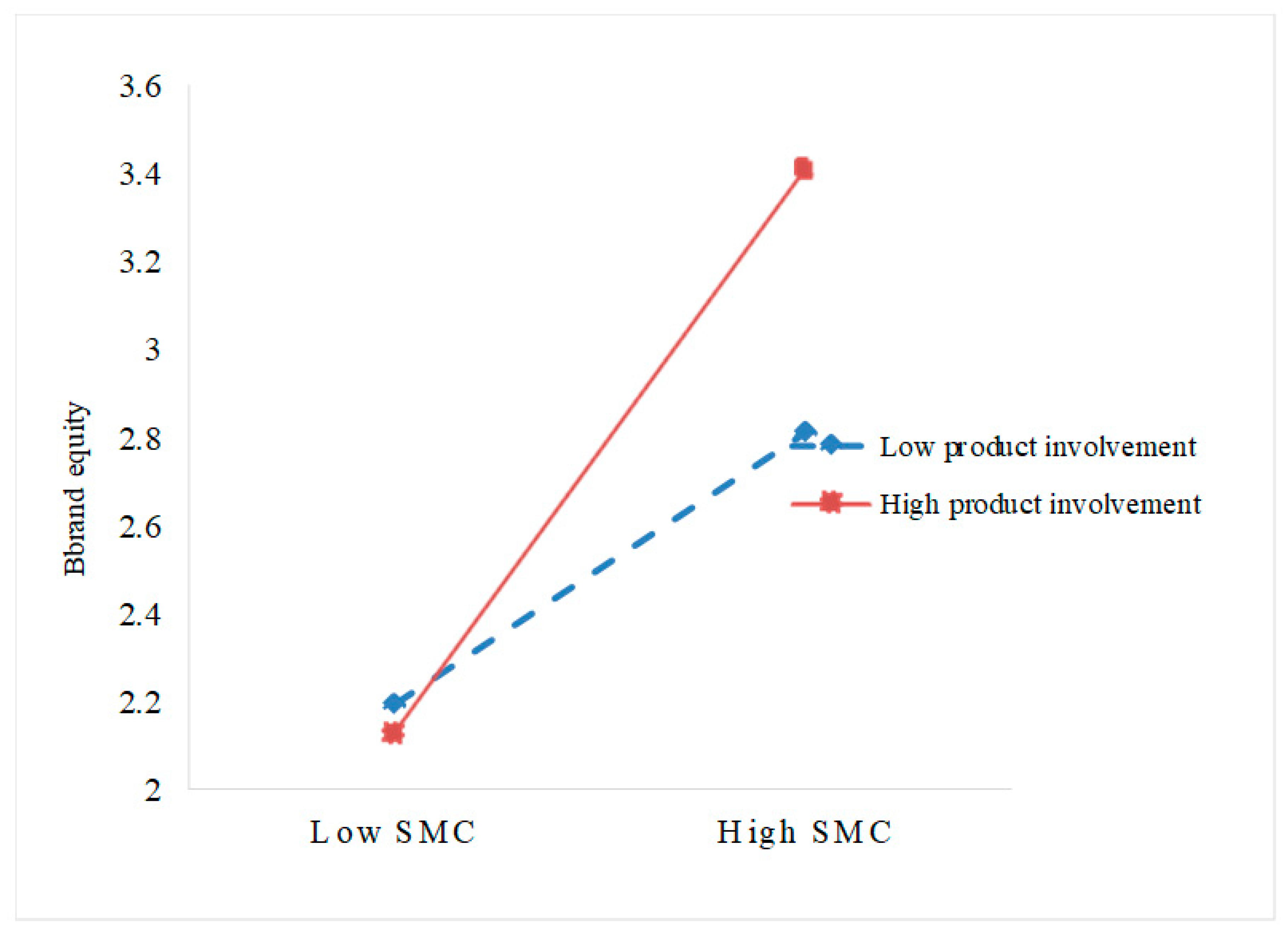

5.4. Tests of Research Hypotheses: Moderating Relationships (Moderating Effect of PI)

In this study, PI was used as a moderator factor to study the relationship between SMC and BE. Mediator and moderator analyses were conducted using the PROCESS Model 5 macro for SPSS [78] with 5000 bootstrap resamples. The results in Table 6 reveal an important role for SMC and PI interactive item (β = 0.3297, confidence interval = [0.2342, 0.4251], p < 0.05) in BE prediction in support of H5. Compared to the respondents with low PI, those with high PI can enhance the influence of SMC on BE. It can be seen from Figure 3, which contains a slope analysis, that SMC has a significant positive predictive effect on BE in both subjects with higher or lower levels of PI. However, this predictive effect is relatively small in the low- as compared to the high-PI situation, indicating that the predictive effect of SMC on BE shows a gradual upward trend as the level of PI increases. In addition, we studied whether demographic characteristics as control variables can affect BE in the model relationship. We found that age, but not gender, education level, or income, can significantly influence BE. This may be related to both self-efficacy and alongside aging processes such as accrued life experience, since younger adults are more prone to engage in opportunities to learn new technologies [80].

Table 6.

The moderating role of PI on the relationship between SMC and BE.

Figure 3.

Moderating role of PI on the relationship between SMC and BE.

Finally, a summary of all research hypotheses with statistically significant effects is contained within Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of results.

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussions

The main purpose of this paper was to assess the comprehensive model relationship among SMC, e-WOM, PI, and BE. A summary of the analyses of these results and discussion are presented below. First, we found SMC generated by a firm has a positive effect on e-WOM. Social media sites are considered as reliable platforms for e-WOM [81], as they allow companies or ordinary consumers to share their feelings and experiences through text messages, pictures, videos, and other content. As a result, e-WOM becomes more attractive and appealing [82]. In support of our H1b hypothesis are results demonstrating that SMC generated by users exerts a positive effect on e-WOM. Consistent with the findings of Campbell et al. [83], users can use social media platforms, such as YouTube, to post comments and offer suggestions which can then trigger the sharing of brand conversations. Taken together, these findings indicate that social media provides consumers with unlimited opportunities to promote e-WOM communication. Similarly, Park and Shin et al. have also recently reported that the usefulness of SMC information has a positive impact on the communication and adoption of e-WOM [84]. Second, Schivinski and Dabrowski [85] have proposed that SMC generated by companies has a positive impact on perceived brand quality, association, and awareness, while Kumar et al. [86] stated that social media content created by consumers can also significantly affect the attitude and behavior of customers. The findings of Zollo et al. indicate that SMC campaigns impact BE and are particularly effective if they address digital consumer interests and provide a positive brand experience [44]. Further, Kumar et al. [86] also note that attitudes toward UGC have a positive impact on BE and purchase intentions [11]. These points are related to our H2a, b hypothesis. Results from previous studies have also supported the precept that e-WOM plays an important role in providing information about brands and enhancing the exchange of opinions and experiences about products and services, all of which may then enhance BE appeal [87]. Sun et al. provided the first empirical validation demonstrating that e-WOM exerts a positive impact on BE when considering consumer perceptions of domestic and foreign brands in an important emerging market, like China [88]. These concepts are consistent with our H3 hypothesis that e-WOM has a direct positive effect on BE.

We not only examined the effects of direct relationships between the models but also focused on the influence of e-WOM as a mediating factor on the independent variable, SMC, and the dependent variable, BE, as contained within our H4a and H4b hypotheses. The results obtained do, in fact, show that e-WOM is an important mediator of the above relationships. In previous research, e-WOM has been shown to play a vital role in the sharing, discussion, and interaction processes among social media users [89]. That is, user-generated and FGC related to brand information can promote e-WOM behavior, thereby promoting an enhancement of BE. Finally, we also evaluated the moderating effect of PI on the model as part of our H5 hypothesis and found that different levels of PI also exert a moderating effect on SMC and BE. In this study, we found that, as compared with that of low-involvement customers, high-involvement customers play a stronger role in promoting a positive relationship between SMC and BE.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This research was initiated with the concept of a brand’s SMC strategy, and, based on U&G and SIT theories, generated the proposal that SMC represents a relatively low-cost resource that brands can employ in the process of accumulating BE. Existing literature also supports the view that SMC has increased interactions, trend identifications, customization, sale activity information, and word of mouth, all factors which can affect consumers’ attitudes and behaviors toward brands [90]. BE may be incorporated into a company’s strategy to help it expand, become more competitive, and promote sustainable brand development. Thus, this research has implications for academics and practitioners as both companies and consumers acknowledge the value of brand-related communication on social media. The theoretical significance of this report resides in relating the importance of SMC, e-WOM, and PI in sustainable social media marketing and sustainable brand management.

First, we provide important evidence that provides a means to understand the relationship among SMC, e-WOM, and BE. We established a causal relationship, determine correlations between these structures and provide experience for this relationship framework support, along with a better understanding of this concept, all of which contribute to the development of the theory. Second, by analyzing the mediating role of e-WOM, the findings presented here highlight the potential of e-WOM’s influence on BE. In this way, we not only respond to previous research requests, but also extend social media marketing research to propose a potential mediating role of e-WOM between SMC and BE, thus emphasizing the intrinsic process and contribution to theoretical research.

The impact of PI on consumer behavior has received relatively little attention. In this report, we supplement the findings of previous studies by conducting a follow-up investigation directed at determining the relationship between SMC and BE based on the differences in high and low PI. Here, we emphasize the predictive effects of PI on BE, demonstrate the importance of PI as a moderating factor in the context of SMC, and expand upon the knowledge of brand management in terms of differences in PI.

6.3. Practical Implications

This study offers numerous practical implications with regard to sustainable social media marketing and branded SMCs. First, our findings suggest that SMC has a positive impact on BE. The growing importance of SMC activities in achieving brand sustainability is driving brands to make sustainability a priority and a core management objective. Therefore, brands should continue to use social media platforms as an important mechanism to establish and maintain BE. With use of live broadcasts, videos, and other SMC forms, brands can facilitate consumer’s understanding of the product, create a notable and interesting image of the brand, its product and firm, as well as integrate vivid, novel, and entertaining information into the brand story, all of which can increase promotion. For example, environmental advertising is the most prominent sustainability dimension and the one most frequently used by fashion brands, as reliable companies can create a positive brand reputation through corporate social responsibility and commitment to environmental and social issues [44]. The higher the public brand reputation, the higher the sustainable growth of BE. Thus, marketers should develop and manage their content within a variety of social media platforms. Social media e-WOM of consumer comments, opinions, and praise posted on social media serve as important components of brand communication, which enhances the potential for the brand to be viewed positively and thus enhances BE. Marketers should be aware of the necessity to expand upon their skill sets and build a comprehensive set of skills to enable e-WOM management. Such results can be used to design marketing strategies, to promote sustainability efforts and to position yourself as an increasingly aware promoter of brand sustainability.

Second, we found that e-WOM exerts a positive mediating effect between SMC and BE. Managers can also motivate and guide consumers to generate content related to products and brands, a process which would then help companies better understand consumers’ views on brands, products, and companies. Precise marketing and personalized marketing are important elements of sustainable marketing. If this process is neglected and there is no further analysis of consumers’ potential needs, other than simply finding new customer groups, the cost of social media marketing will continue to rise, making it difficult to achieve BE accumulation and sustainable brand development. Brands should be well aware that effective processes built around UGC and word-of-mouth represent significant mechanisms for development of a successful business model and, it is also possible to formulate better e-WOM strategies by considering consumers’ expectations.

Finally, it is also worth noting that the nearer a brand is to the ideal self of consumers, the more likely consumers will invest in the process of understanding the brand’s product and acquire an attachment to the brand. Differences in PI have led to different levels of customer input. Ideally, companies should establish more specific user review management plans and implement varying product or brand knowledge dissemination strategies based on consumers’ PI. Rather than directly guiding purchases, a step-by-step strategy would nurture social media users to transition them into long-term brand advocates. We should actively build and be effective in managing communications between consumers and consumers, consumers and brand/companies, and encourage customers to post more high-quality reviews and establish partnerships with consumers through hierarchical planning and setting. Senior commentators should not only serve as opinion leaders in the industry but also as spokespersons for their brands or products. In short, the use of social media to enhance communication and interaction between brands and consumers can help maintain good long-term relationships between brands and consumers, enhance BE, and achieve sustainable development of marketing and brands.

6.4. Limitations of the Research

Like all research, this report has limitations and will require further research. First, the influence of some potentially influential variables, such as culture and nationality, were not incorporated within the proposed hypotheses [91]. These variables may exert a moderating effect on the range of determinants among SMC, e-WOM, and BE. The time and expense required for conducting this research precluded such a comprehensive analysis. Future research will need to include these variables and collect larger samples from different countries, such as conducting multi-group comparative analyses among respondents of different cultures, genders, and other variables across countries. Second, the use of self-management questionnaires may generate bias. Subjective scoring of the questionnaire by the survey respondents may also produce biases, which may produce different results when applied to different industries [92]. Finally, our study investigated Chinese consumers, and finally selected Weibo and Bilibili etc. among the social media platforms for the study. However, according to Coelho et al. [93], the impact and popularity of various content on Facebook and Instagram may differ. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be applied to all social media platforms, and future research and discussion should be extended to other overseas social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. In summary, future research in this area should primarily be directed toward expanding this model with the addition of other important constructs that may influence each driver of BE. In addition, this work should include a larger sample size, more diverse cultures and ages, as well as different platforms for future comparative studies to demonstrate the generalizability of the relationship between SMC and BE variables.

Author Contributions

Conceiving research and designing research framework: W.D. and S.N. Collecting and analyzing data: K.L., S.Y. and C.L. Writing the paper: K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of constructs and measurements used.

Table A1.

List of constructs and measurements used.

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm-generated communication | The company’s social media communications for brand are very attractive. | 0.857 | 0.870 | 0.883 | 0.654 |

| This company’s social media communications for brand perform well, when compared with the social media communications of other companies. | 0.853 | ||||

| The level of the company’s social media communications for brand meets my expectations. | 0.788 | ||||

| I am satisfied with the company’s social media communications for brand. | 0.756 | ||||

| User-generated communication | The content generated on social media sites by other users about brand performs well, when compared with other brands. | 0.868 | 0.901 | 0.907 | 0.709 |

| The content generated by other users about brand is very attractive. | 0.851 | ||||

| The level of the content generated on social media sites by other users about brand meets my expectations. | 0.842 | ||||

| I am satisfied with the content generated on social media sites by other users about brand. | 0.821 | ||||

| e-WOM | If my friends were looking to purchase something, I would tell them to try [Brand] on social media. | 0.861 | 0.849 | 0.867 | 0.685 |

| I would recommend [Brand] products to my friends on social media. | 0.833 | ||||

| If my friends were looking to purchase something, I would tell them to try [Brand] on social media. | 0.832 | ||||

| Brand equity | If another brand is not different from brand in any way, it seems smarter to purchase brand. | 0.803 | 0.895 | 0.900 | 0.693 |

| It makes sense to buy brand instead of any other brand, even if they are the same. | 0.793 | ||||

| Even if another brand has the same feature as brand, I would prefer to buy brand. | 0.783 | ||||

| If there is another brand as good as brand, I prefer to buy brand. | 0.782 | ||||

| Product involvement | When I am looking for the online comments, I think the product is valuable to me. | 0.856 | 0.930 | 0.934 | 0.701 |

| When I am looking for the online comments, I think the product is useful to me. | 0.844 | ||||

| When I am looking for the online comments, I think the product is attracting to me. | 0.843 | ||||

| When I am looking for the online comments, I think the product is meaningful to me. | 0.837 | ||||

| When I am looking for the online comments, I am interested in the product. | 0.837 | ||||

| When I am looking for the online comments, I think the product is important to me. | 0.804 |

References

- Fuchs, C. Baidu, Weibo and Renren: The global political economy of social media in China. Asian J. Commun. 2016, 26, 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger, P.J., III. Exploring synergetic effects of social-media communication and distribution strategy on consumer-based Brand equity. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2020, 10, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.J.; Kim, Y. Research trends of sustainability and marketing research, 2010–2020: Topic modeling analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarvizhi, C.A.; Al Mamun, A.; Jayashree, S.; Naznen, F.; Abir, T. Modelling the significance of social media marketing activities, brand equity and loyalty to predict consumers’ willingness to pay premium price for portable tech gadgets. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella-Ramón, A.; García-de-Frutos, N.; Ortega-Egea, J.M.; Segovia-López, C. How does marketers’ and users’ content on corporate Facebook fan pages influence brand equity? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; Vinhas da Silva, R.; Hair, J.F. Towards a unified theory of brand equity: Conceptualizations, taxonomy and avenues for future research. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Rust, R.T.; Zeithaml, V.A. What drives customer equity? Mark. Manag. 2001, 10, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Khan, B.M. The Role of Social Media Communication in Brand Equity Creation: An Empirical Study. IUP J. Brand Manag. 2019, 16, 54–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Choi, J.B.; Greene, M. Synergistic effects of social media and traditional marketing on brand sales: Capturing the time-varying effects. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, M.; Hamzah, M.I. Should I suggest this YouTube clip? The impact of UGC source credibility on eWOM and purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mooij, M. Brand Equity. Education Directorate of the International Advertising Association, Amsterdam, September. Directions. J. Interact. Mark. 1993, 23, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- King, C.; Grace, D. Building and measuring employee-based brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 938–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, P.H. Managing brand equity. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K. Social media marketing and customers’ passion for brands. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I.; Veloutsou, C. Working consumers: Co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ko, E.; Woodside, A.; Yu, J. SNS marketing activities as a sustainable competitive advantage and traditional market equity. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickart, B.; Schindler, R.M. Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information. J. Interact. Mark. 2001, 15, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godes, D.; Mayzlin, D. Firm-created word-of-mouth communication: Evidence from a field test. Mark. Sci. 2009, 28, 721–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. The influence of social media marketing activities on customer loyalty. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3882–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castronovo, C.; Huang, L. Social media in an alternative marketing communication model. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2012, 6, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gensler, S.; Völckner, F.; Liu-Thompkins, Y.; Wiertz, C. Managing brands in the social media environment. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K.S.; Bruhn, M.; Schoenmueller, V.; Schäfer, D.B. Are social media replacing traditional media in terms of brand equity creation? Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.-Y.; Heng, C.-S.; Lin, Z. Social media brand community and consumer behavior: Quantifying the relative impact of user-and marketer-generated content. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Social media content aesthetic quality and customer engagement: The mediating role of entertainment and impacts on brand love and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, T.; Eastin, M.S.; Bright, L. Exploring consumer motivations for creating user-generated content. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 8, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W. Developing UGC social brand engagement model: Insights from diverse consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulussen, S. User-Generated Content. Int. Encycl. Journal. Stud. 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.R.; Pitt, L.F.; McCarthy, I.; Kates, S.M. When customers get clever: Managerial approaches to dealing with creative consumers. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegner, C. Word of mouth on the web: The impact of Web 2.0 on consumer purchase decisions. J. Advert. Res. 2007, 47, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Broderick, A.J.; Lee, N. Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, G.; Michaelidou, N.; Argyriou, E. Cross-national differences in e-WOM influence. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1689–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Fischer, E.; Yongjian, C. How does brand-related user-generated content differ across YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter? J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesschaeve, I.; Bruwer, J. The importance of consumer involvement and implications for new product development. In Consumer-Driven Innovation in Food and Personal Care Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 386–423. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, R.A.; Price, L.L.; Feick, L. Rethinking the origins of involvement and brand commitment: Insights from postsocialist central Europe. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.-J.; Park, J.-W. A study on the effects of social media marketing activities on brand equity and customer response in the airline industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 66, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Chang, L.H. Determinants of habitual behavior for national and leading brands in China. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2003, 12, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, E.C.; Calder, B.J.; Kim, S.J.; Vandenbosch, M. Evidence that user-generated content that produces engagement increases purchase behaviours. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, L.; Filieri, R.; Rialti, R.; Yoon, S. Unpacking the relationship between social media marketing and brand equity: The mediating role of consumers’ benefits and experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.; Meshreki, H.; Sarofim, S. Brand equity in higher education: Comparative analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, S.; Dellarocas, C.; Godes, D. Introduction to the special issue—Social media and business transformation: A framework for research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-C.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Christou, E.; Gretzel, U. Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, L.; Gensler, S.; Leeflang, P.S. Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungruangjit, W.; Charoenpornpanichkul, K. Building Stronger Brand Evangelism for Sustainable Marketing through Micro-Influencer-Generated Content on Instagram in the Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, J.; Sievert, J.; Jacob, F. How credibility affects eWOM reading: The influences of expertise, trustworthiness, and similarity on utilitarian and social functions. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Lammas, N. Social media and its implications for viral marketing. Asia Pac. Public Relat. J. 2010, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donohoe, S. Advertising uses and gratifications. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The effect of social media communication on consumer perceptions of brands. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Luo, X.R.; Xu, Y.; Warkentin, M.; Sia, C.L. Examining the moderating role of sense of membership in online review evaluations. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.J.; Park, J.-W.; Choi, Y.J. The Effect of Social Media Usage Characteristics on e-WOM, Trust, and Brand Equity: Focusing on Users of Airline Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Gordon, B.S.; Nakazawa, M.; Shibuya, S.; Fujiwara, N. Bridging the gap between social media and behavioral brand loyalty. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 28, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Bilgihan, A.; Okumus, F.; Shi, F. The impact of eWOM source credibility on destination visit intention and online involvement: A case of Chinese tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. Celebrity fashion brand endorsement in Facebook viral marketing and social commerce. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senecal, S.; Nantel, J. The influence of online product recommendations on consumers’ online choices. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J. eWOM overload and its effect on consumer behavioral intention depending on consumer involvement. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Jalilvand, M.; Samiei, N. The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Conceptualizing involvement. J. Advert. 1986, 15, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lee, H. The effects of source credibility, affection, and involvement in reducing the belief of internet rumors. J. Manag. 2005, 22, 391–413. [Google Scholar]

- Goyette, I.; Ricard, L.; Bergeron, J.; Marticotte, F. e-WOM Scale: Word-of-mouth measurement scale for e-services context. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. Lߣadministration 2010, 27, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Chen, C.S. The influence of the country-of-origin image, product knowledge and product involvement on consumer purchase decisions: An empirical study of insurance and catering services in Taiwan. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Shirkey, E.C. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; Mcgraw Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling; University of Kansas: Lawrence, Kansas, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Prakash, G.; Gupta, B.; Cappiello, G. How e-WOM influences consumersߣ purchase intention towards private label brands on e-commerce platforms: Investigation through IAM (Information Adoption Model) and ELM (Elaboration Likelihood Model) Models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. The influence of eWOM in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended approach to information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Pitt, L.F.; Parent, M.; Berthon, P.R. Understanding consumer conversations around ads in a Web 2.0 world. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Shin, J.-K.; Ju, Y. Attachment styles and electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) adoption on social networking sites. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The impact of brand communication on brand equity through Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bezawada, R.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Kannan, P. From social to sale: The effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijoria, C.; Mukherjee, S.; Datta, B. Impact of the antecedents of electronic word of mouth on consumer based brand equity: A study on the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, H.; Wang, S. Examining the relationships between e-WOM, consumer ethnocentrism and brand equity. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, N.H.; Md Ariff, M.S.; Mohd Som, N.; Zakuan, N.; Sulaiman, Z. The mediating effect of brand image between electronic word of mouth and purchase intention in social media. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2016, 22, 3176–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Investigating the impact of social media advertising features on customer purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. Mine your customers or mine your business: The moderating role of culture in online word-of-mouth reviews. J. Int. Mark. 2017, 25, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.L.F.; de Oliveira, D.S.; de Almeida, M.I.S. Does social media matter for post typology? Impact of post content on Facebook and Instagram metrics. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).