Abstract

Green entrepreneurship has become a growing area of interest among researchers and practitioners as it has the potential to address the sustainability challenges faced by the global economy. The purpose of this study is to evaluate six antecedents (self-efficacy, attitude, green consumption commitment, country support, university support, and subjective norms) that can predict the intention to engage in green entrepreneurship among higher education students. A total of 690 higher education students were surveyed, and the results were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results showed that the internal antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention (self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption commitment) have a higher significant predictive power than the external antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention (country support, university support, and subjective norms) among higher education students. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the factors that influence green entrepreneurship intention (GEI) and can be used to inform policy and educational initiatives aimed at promoting green entrepreneurship. The findings of this research could also draw attention from the government and universities who are interested in understanding the factors that influence students’ inclination towards green entrepreneurship. This could lead to the creation of relevant course materials, programs, and funding to promote sustainable initiatives.

1. Introduction

Green entrepreneurship is an increasingly popular approach to business that prioritizes environmental sustainability. As more people become aware of the need to reduce their environmental impact and make a positive contribution to the planet, green entrepreneurship is becoming an attractive option. Green entrepreneurship denotes developing businesses that aim to solve environmental problems and promote sustainability [1]. Countries around the world are pushing to develop green entrepreneurship initiatives as a way to achieve harmony between economic growth, social progress, and environmental sustainability [2]. Higher education students are a significant demographic in the creation of green entrepreneurship projects because they have the skills and knowledge to create businesses [3]. Understanding the antecedents of GEI among higher education students is important for fostering a more sustainable future. A variety of internal and external factors may contribute to shaping GEI among higher education students. Several studies have highlighted the importance of antecedents such as entrepreneurial education, social norms, personal values, and environmental awareness in fostering green entrepreneurship intentions. However, the context of Saudi Arabia’s higher education system is unique, and there is limited research on the antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention in this context.

Green entrepreneurship is a way for entrepreneurs to address the environmental challenges facing the world today and to create economic opportunities for themselves and their communities [4,5]. There has been an increase in interest in recent years about green entrepreneurship, as it has the potential to create economic growth and social benefits while reducing environmental degradation [6,7,8]. However, previous studies that have investigated several internal and external antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions have produced contradictory and mixed results. Some studies have identified specific factors that can positively influence green entrepreneurship intentions, while other factors have a negative impact. For example, a study by Anghel and Anghel [3] employing correlation analysis as the main data analysis technique found that only green knowledge and education (internal factors) have a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions among 120 students in Romania. Similarly, a study by Aliedan et al. [9] employing structural equation modelling (SEM) as the main data analysis technique found that university education support and subjective norms (external factors), personal attitude, and perceived behavior control (internal factors) are significant predictors of green entrepreneurship intentions among 390 students in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Additionally, using a SEM data analysis method, Wang et al. [10] found that other different factors such as entrepreneurial self-efficacy optimism (internal factors), ecological values, and social responsibility (external factors) have a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions among 410 Chinese college students. On the other hand, using multiple linear regression analysis techniques, Aditya [11] found that university education failed to positively impact entrepreneurship intentions among 95 students at Jakarta State University, Indonesia. Similarly, Autio et al. [12] conducted international comparisons of samples from Finland, Sweden, United States of America (USA), and the United Kingdom (UK) and found that perceived behavior control (PBC) is the most important determinant of entrepreneurial intention, while subjective norms (external) have a negative impact on entrepreneurial intentions (internal). Likewise, Al-Jubari [13] conducted an empirical study on 622 college students in Yemen employing structural equating modelling and found that attitude and PBC can predict entrepreneurship intentions while subjective norms negatively influence entrepreneurship intention. These mixed results indicate that the factors that influence green entrepreneurship intentions may vary depending on methodological, cultural, and socioeconomic contexts. Overall, the mixed results of previous studies highlight the need for further research to better understand the factors that influence green entrepreneurship intentions in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. The current research can contribute to bridging this gap by investigating several internal and external antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions in one model using a large sample size (690 responses) and an advanced data analysis technique (PLS-SEM) in the context of Saudi Arabia.

Furthermore, despite the growing interest in green entrepreneurship, there is a significant research gap in the antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions among Saudi Arabia’s higher education. Specifically, there is a lack of empirical research on the role of cultural and social norms, the influence of government policies, and the impact of entrepreneurial education on green entrepreneurship intentions in the Saudi Arabian context. While some studies have examined the factors that influence traditional entrepreneurship intentions in Saudi Arabia, there is a lack of research on how these factors apply to green entrepreneurship. The current study seeks to overcome this gap in the literature by exploring the aspects that induce the intention to engage in green entrepreneurship among university students in the context of Saudi Arabia. The study focuses on young entrepreneurs because they are the future leaders of the economy and have the potential to drive change and create a more sustainable future [9]. Addressing this gap could provide important insights into the factors that drive green entrepreneurship intentions in Saudi Arabia and contribute to sustainable economic development. Further empirical research is needed to understand the unique cultural, social, and economic factors that influence green entrepreneurship intentions in the Saudi Arabian context. The research will add to the body of literature by providing valuable insights into the factors that affect GEI and by informing policy and educational initiatives aimed at promoting green entrepreneurship.

The remainder of our research is organized as follows: In Section 2, we highlight the theoretical background of our research. Section 3 discusses literature review and hypotheses development. In Section 4, we show research materials and methods. Section 5 includes data analysis and results. In Section 6, we discuss and conclude research results. Section 7 reveals the implications of the current study. Finally, Section 8 shows limitations and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) as introduced by Ajzen [14] is a well-established theoretical framework that can be applied to understand the antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions in Saudi Arabia’s higher education. The TPB suggests that an individual’s behavior is determined by their intention to perform that behavior, which is influenced by their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Planned behavior theory is frequently used in entrepreneurship intention research and provides a practical framework for understanding the elements influencing such entrepreneurial behavior [15,16]. Our study extends this theory beyond just attitudes and subjective norms and considers additional internal factors, such as self-efficacy and green consumption commitment, and external factors, such as country and university support. Examining these factors can offer insights into the cultural and educational influences that impact green entrepreneurship intentions within the Saudi Arabian context. These findings can be utilized to shape policy and educational efforts aimed at promoting green entrepreneurship.

2.1. Internal Antecedents of Green Entrepreneurship Intentions

Internal antecedent factors of GEI include self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption dedication. Attitude and subjective norms are two other important factors that can predict green entrepreneurship intentions. An individual’s attitude can be described as their assessment of whether an activity, such as launching a green business, is positive or negative [17]. Research has shown that positive attitudes towards green entrepreneurship may result in greater intentions to initiate a green enterprise. For example, Soomro et al. [18,19] found that green business attitudes are more likely to react based on green entrepreneurship preferences. Additionally, Nguyen et al. [20] reported that individuals who held more positive attitudes towards environmental sustainability were more likely to express intentions to start a green business. This highlights the importance of attitudes in shaping green entrepreneurship intentions. Hence, we can propose the below hypothesis:

H1:

Attitude towards green entrepreneurship has a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

Additionally, green consumption commitment is an important factor that can predict green entrepreneurship intentions. Green consumption commitment refers to an individual’s willingness to adopt environmentally friendly consumption behaviors. This concept shows a significant impact on green entrepreneurship intentions. It was found that people with a strong commitment to green consumption are more inclined to possess a favorable viewpoint toward green entrepreneurship and a greater intention to start a green business [21]. This highlights the importance of green consumption commitment in shaping green entrepreneurship intentions. Another study [22,23] found that individuals who have a higher level of green consumption commitment are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors, such as starting a green business. This suggests that a strong commitment to green consumption can drive individuals to take actions that support environmental sustainability. Therefore, we can suggest the below hypothesis:

H2:

Green consumption commitment has a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

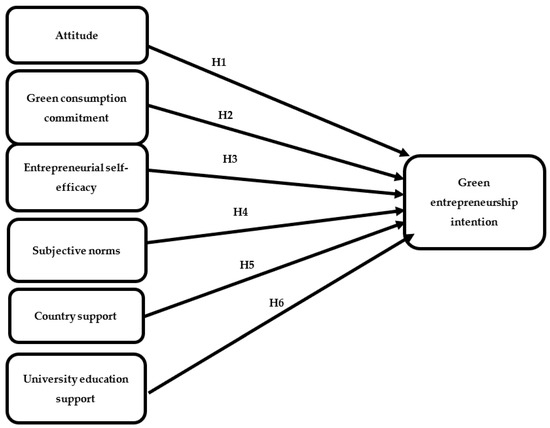

Awareness of green entrepreneurship can be influenced by people’s behavior (self-efficacy) [24]. As people become more aware of the impact of their purchasing decisions on the environment, they are increasingly seeking out environmentally friendly products and services. This has created a demand for environmentally responsible businesses and has encouraged companies to adopt sustainable business practices [18]. Many previous studies proved the empirical positive effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurship intentions [25,26,27]. Based on the above discussion (as shown in Figure 1) we can propose the below hypothesis:

Figure 1.

The proposed research framework.

H3:

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy has a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

2.2. External Antecedents of Green Entrepreneurship Intentions

External factors include country support, university support, and subjective norms. Country support is one of the most important considerations that may have an influence on GEI among students at higher education institutions. GEI can be influenced by government policies and initiatives to promote sustainable business practices. For example, many countries have implemented policies and regulations to encourage companies to implement measures that are beneficial to the environment, such as cutting back on the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere, conserving natural resources, and improving waste management [10,28,29,30,31,32]. If students are given legal backing for green business initiatives, they will have the confidence to initiate such projects [2] and will be more likely to pursue them [24].

The second factor that may affect green entrepreneurship intention is university support. Educational programs and training initiatives aimed at promoting green entrepreneurship awareness can help to increase understanding of the importance of sustainable business practices. These programs can be targeted at business owners, entrepreneurs, students, and other stakeholders, and can include topics such as sustainable business practices, environmental stewardship, and corporate social responsibility. Students’ ability to succeed in business is significantly impacted by the issue of startup business support at universities [33,34,35,36,37]. Therefore, universities are currently actively supporting startup ideas related to the level of environmental protection [38]. Moreover, Qazi et al. [39] argue that universities should include green entrepreneurship in their educational support programs. This would create a university environment that is conducive to green business, providing graduates with the necessary business competences and expertise in addition to the ability to start their own green businesses. Furthermore, colleges are having a positive effect on green entrepreneurship and business by instilling green business goals in students, and universities will be critical in transforming green entrepreneurship intentions into a successful green entrepreneurship business [20,40].

The third external factor is subjective norms. Subjective norms are known as individuals’ beliefs about what other people expect them to do or not do in a given situation. These are the perceived social pressures that influence an individual’s choice to take part in a certain activity or not [20]. Early exposure to challenging business conditions is expected to increase individual autonomy and positive attitudes towards self-employment [39]. According to [41], one of the factors driving personal business aspirations are subjective norms that influence students’ entrepreneurship intentions. Moreover, empirical research results find that subjective norms are a good predictor of entrepreneurial intentions [17,42]. More specifically, [20] reported a positive impact for subjective norms on green entrepreneurship. It was found that individuals who faced more social pressure to start a green business were more likely to have green entrepreneurship intentions [40,43]. This suggests that the opinions and beliefs of important close personalities, such as family, friends, and business associates, can influence a person’s intentions to start a green business. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be formulated:

H4:

Subjective norms have a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

H5:

Country support towards green entrepreneurship has a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

H6:

University education support towards green entrepreneurship has a positive impact on green entrepreneurship intentions.

3. The Saudi Arabian Context

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has made significant moves towards a sustainable future following the initiation of Vision 2030 in 2016. Several green initiatives were launched within the agenda of vision 2023, such as the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI), the Middle East Green Initiative (MGI), and the Green Riyadh Project [44]. These green initiatives have created a fertile ground for green entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. The government has launched several programs to support green entrepreneurs and startups and offers funding, training, and mentoring to green businesses. Our study has been carried out in the Saudi setting for a number of reasons. First, one of the goals of the Saudi Vision 2030 is to reduce the unemployment percentage from 11.6% to 7%. In addition, it seeks to increasing the involvement of the entrepreneurial sector and small and medium enterprises (SME) in the nation’s GDP from 20% to 35% [35]. Second, the revenues of Saudi Arabia depend considerably on oil prices. However, the worldwide fluctuation in the price of oil results in deficits in the budget of the country. Hence, Saudi Arabia is speedily shifting in the direction of expanding sources of revenue, including the focus on entrepreneurship. Third, the Saudi General Authority for Statistics pointed out that the young generation in Saudi Arabia with ages ranging between 15 and 34 years represents 36.7% of the entire population of the country. Thus, one of the important development directions in Saudi Arabia is to support the entrepreneurial sector, specifically young people and the university students who represent an important part of this group. To this end, these discussions draw attention to the existence of an entrepreneurship intention gap in the Saudi context, which we try to bridge in this study.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

To achieve the goal of the present study, a quantitative cross-sectional survey approach was employed. Prior literature was extensively examined to create study measures and establish the research framework, which led to the formulation of research hypotheses. Subsequently, an online questionnaire was utilized to gather primary empirical data, which was then analyzed using the PLS-SEM analysis method. Data were collected through an online self-administrated questionnaire from the targeted students in their final year and recent graduates in four colleges (business administration, arts, computer science, and engineering). These students had taken courses related to management and entrepreneurship. The study used a questionnaire with recognized and validated scales that identified six factors, including attitude, green consumption commitment, self-efficacy, university education support, country support, and social norms, as the most common predictors of entrepreneurial intention. The study categorized these factors into internal (attitude, green consumption commitment, and self-efficacy) and external (university education support, country support, and social norms) antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions. The questionnaire was tested for clarity, consistency, and simplicity by a group of 10 professors and 20 senior students, and no changes were made to the original questionnaire items.

The questionnaire had three sections: The first part gathered demographic evidence such as age, gender, and college. The second section assessed GEI using a seven question scale adapted from Liñán and Chen [45] and Hsu and Wang [46]. The third part of the questionnaire focused on the factors that influence GEI, with a total of 26 questions across six dimensions. The internal antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions, consisting of attitude, green consumption commitment, and self-efficacy, were evaluated using 4 items each. The specific items used for attitude were taken from Ajzen [47], while the items for green consumption commitment were adapted from Zeithaml et al. [48] and the items for self-efficacy were suggested by Soria-Barreto [49]. Likewise, the external factors (outside of personal influence) that contribute to green entrepreneurship intentions consist of country support, as assessed by Alvarez-Risco [24], university education support consisting of four items adapted from Yi [2], and subjective norms, which were measured by five items proposed by Ajzen [47]. These factors were included in the questionnaire due to their relevance to green entrepreneurship intentions, previous research, and empirical understanding; they demonstrated good psychometric characteristics according to previous studies [50,51,52,53,54].

4.2. Data Collection Process

We gathered the specific data needed for our research by conducting an online survey using a quantitative approach. This survey was shared through social media platforms and official university emails; it was sent to both recent graduates and current senior students during April and May 2022. We obtained the questionnaires for our study using a non-probability convenient sampling method in order to reach out to a variety of senior students and recent graduates and assess their perception of their entrepreneurial abilities. We specifically targeted this group because they may be considering entrepreneurship as a potential career path. It is worth noting that fresh graduates, i.e., individuals who have recently completed their academic studies usually at the undergraduate or postgraduate level and are seeking employment opportunities in Saudi Arabia, can receive various forms of support from public universities. Support includes technical, marketing, and financial assistance to help them start and manage their own businesses. We received 720 responses to the questionnaire from students. After carefully reviewing the submissions, we deemed 690 of them to be valid, resulting in a response rate of 95%.

We utilized SPSS software to investigate any missing data in our study and found that around 30 out of 720 questionnaires (more than 5%) had some random missing scores. We decided to exclude these questionnaires as they could have a significant impact on the accuracy of our research findings. As a result, we used 690 valid questionnaires in our study. Furthermore, we checked for outliers in our scale variables using the boxplot in SPSS and found none. All students who participated in our study were fully informed about the purpose of the research and provided their consent to participate voluntarily in the survey.

4.3. Statistical Analysis Methods

Partial least squares-based structural equation modeling, also known as PLS-SEM, is a method that is appropriate for evaluating and confirming the initial phases of theory formation [55]. This technique is advantageous for performing multivariate analysis [56]. PLS-SEM is a statistical technique that does not rely on strict assumptions about the underlying data and utilizes the variance in unobserved dimensions known as latent variables. It is commonly used in management research and has a reputation for generating dependable outcomes [57]. Smart PLS-SEM is frequently utilized for analyzing the connections between different variables. Additionally, as recommended by [55], we employed 5000 bootstrap repetitions with a sample size of 690 to establish the significance of the path coefficient and obtain more precise coefficient values.

4.4. Common Method Variance

To minimize the possibility of common method variance (CMV) in our study, we employed several pre-emptive techniques in the research design, in line with the recommendations of Lindell and Whitney [58] and Podsakoff et al. [59]. During the questionnaire development process, steps were taken to reduce this bias [60]. For example, the dependent variables were presented before the independent variables, following the advice of Salancik and Pfeffer [61]; the the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were also ensured. To ensure the questionnaire’s reliability and clarity, ten academics and twenty students piloted the survey questions. No modifications were made to the questionnaire following the pilot test. The survey was initially written in English, then professionally translated into Arabic (the participants’ native language) and then back into English. Finally, Harman’s single-factor analysis was conducted. The factors obtained had a score of 1.00 in an exploratory factor analysis test using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) with no rotation. Only one factor emerged explaining 38% of the variance and indicating that CMV was not a concern in our study.

5. Results

5.1. Sample Properties and Descriptive Analysis

This study included 690 valid participants from King Faisal University comprising 45% male and 55% female students. The majority of students (95%) were under 25 years old, as anticipated. The participants’ academic backgrounds were diverse with 30% coming from the business administration college, 23% from the college of arts, 22% from the computer sciences college, and 25% from the engineering college. As seen in Table 1, out of the 690 participants, 70% were senior students and the remaining 30% were fresh graduates. Fifteen per cent of respondents reported having experience running their own businesses, while 85% reported having experience working in either the private or public sectors. After examining the study for missing data using the SPSS package, it was found that there were missing scores in 30 out of 720 questionnaires, which was greater than 5%. As a result, these questionnaires were eliminated to avoid any potential impact on the research results. This left a total of 690 valid questionnaires for the study. Additionally, a boxplot was used to check for outliers in the scale variables and none were found. Moreover, as per Nunnally’s [62] criteria, neither the skewness nor kurtosis of the data exceeded −2 or +2, implying that the data exhibited a normal distribution. Moreover, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the study items we found to be less than 0.5, indicating the absence of any multicollinearity issues [63].

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

5.2. Measurement Model Assessment

As recommended by Leguina [56], we estimated the validity and reliability of the measurement model in our study before examining the structural model. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 provide the results of these evaluations. To evaluate the reliability of the dimensions, we used both composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha as suggested metrics.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity measures of the study construct.

Table 3.

Heterotrait—monotrait ratio (HTMT)-Matrix.

Table 4.

Loadings and cross-loadings for discriminant validity.

As suggested by Hair et al. [55], both composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (a) values should be higher than 0.7. In this study, all employed dimensions demonstrated CR and a values exceeding the recommended threshold values, including attitude (C_R = 0.982, a = 0.979), country support (C_R = 0.970, a = 0.980), green consumption commitment (C_R = 0.978, a = 0.978), green entrepreneurship intention (C_R = 0.960, a = 0.962), self-efficacy (C_R = 0.975, a = 0.970), subjective norms (C_R = 0.989, a = 0.979), and university support (C_R = 0.898, a = 0.889). Therefore, the dimensional reliability meets the conditions. The results are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Additionally, the study evaluated the factor load of each measurement item and found that it exceeded 0.7 (Table 3), indicating appropriate variable reliability [35]. Convergent validity of the employed measurement scales was also assessed. To meet the criterion of an adequate amount of construct convergence validity [64,65,66], the average variance extracted (AVE) value of all dimensions should be greater than 0.50. The results, as presented in Table 2, indicate that all AVE values exceeded 0.5, thus satisfying the convergence validity criteria.

In addition, to ensure that the study has adequate discriminant validity, the correlation coefficients between all factors should be less than the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) as suggested by the Fornell–Larcker conditions [67]. Moreover, the square root of AVE values should not be less than 0.7 [65]. As shown in Table 2, the diagonal values represent the square root of the factors’ AVE, while the non-diagonal scores are the correlation coefficient between dimensions. The numbers in the table fulfill the criteria for proper discriminant validity. In addition, [56,68] recommendation of a heterotrait–monotrait ratio below 0.90 was met by the values obtained in the study (see Table 3). These findings indicate that the measures utilized in the research exhibit strong reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity, thus allowing for hypothesis evaluation through analysis of the inner structural model.

5.3. Structural Model Findings

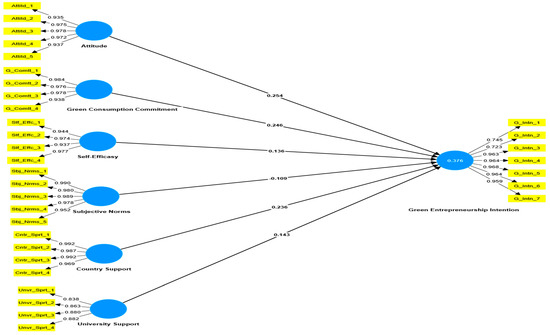

Once the appropriateness of the measurement model was confirmed, the proposed structural model was assessed. In accordance with Hair et al.’s [55] recommendations, 5000 bootstrap samples were employed to assess the significance level of the path coefficients. The path coefficients and corresponding p values are presented in Table 5 and Figure 2.

Table 5.

The proposed hypotheses results.

Figure 2.

The tested research model.

The findings from the analysis of the proposed model are depicted in Figure 2 and Table 5. The findings indicate that the three internal antecedents of GEI (attitude, green consumption commitment, and self-efficacy) have a significant and positive influence on green entrepreneurship intentions among both senior and fresh graduate students. The regression weight values for attitude (β = 0.254, t = 7.113; p < 0.001), green consumption commitment (β = 0.246, t = 7.193; p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (β = 0.136, t = 4.239; p < 0.001) were statistically significant, thus providing support for H1, H2, and H3. The results indicated that two of the external factors influencing GEI, namely country support and university support, had a positive effect on GEI among students, with β values of 0.236 (t = 7.012, p < 0.001) and 0.143 (t = 3.577, p < 0.001), respectively, thus confirming H5 and H6. However, the impact of subjective norms on GEI was negative but significant (β = −0.109, t = 2.868, p < 0.001) which means that H4 was not supported. These findings were also illustrated in Figure 2 and presented in Table 5.

The study also evaluated the predictive power of Q2, which suggests that a value greater than 0 indicates a suitable predictive relevance [56]. The results of the PLS-SEM showed that the Q2 value for green entrepreneurship intention was 0.362, suggesting that our model had appropriate predictive significance power. To estimate the explanatory power of the suggested model, the determination coefficient R2 was employed. A higher score of R2 implies greater explanatory power. Falk and Miller [69] argued that R2 scores greater than 10% have satisfactory explanatory power. In this study, the R2 value for green entrepreneurship intentions was 0.376, exceeding the recommended level. Overall, the proposed model in the study had sufficient explanatory power. In addition, the goodness of fit (GoF) of the model is another important indicator. According to the suggestion of [55], a standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) value < 0.05 and the normed fit index (NFI) value > 0.90 indicate good model fit. In our study, the estimated model’s SRMR and NFI values were 0.047 and 0.953, respectively, indicating that the proposed model was a good fit for our sample data.

6. Discussion

Recent years have witnessed cultural modifications in the direction of growth of ecologically friendly initiatives such as green entrepreneurship. It is evident that there is a massive role for green entrepreneurship in resolving social and environmental problems. Since the youth of today are the entrepreneurs of tomorrow, increasing their intentions toward green entrepreneurship may boost the sustainable growth of the economy in the future [70]. Motivated by this, the current study aims to investigate and offer novel insights into the antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions among millennials, who in our study are represented by higher education students at universities in Saudi Arabia. Using survey data, a model that investigates and assesses the internal antecedents (self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption commitment) and external antecedents (university education support, country support, and subjective norms) was built.

The results of our model provide support for five out of six developed hypotheses. Starting with the internal antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention among students in higher education, we find that attitude has a substantial positive influence on the students’ green entrepreneurship intentions. Hence, hypothesis (H1) is supported. This means that Saudi students’ attitudes enable them to have an encouraging vision concerning green entrepreneurial intentions. This outcome supports the preceding works by [71,72] who found that the wish to be involved in entrepreneurship can be reinforced by the constructive and positive attitude of students. Similarly, Nguyen et al. [20] confirmed that sustainable development and the green economy can be enhanced by inspiring the modification of individuals’ thoughts and attitudes about society, leading to great changes in views concerning green actions, principally in the university environment. Furthermore, our results lend support to those of Autio et al. [12] and Gird and Bagraim [73] in that those green entrepreneurial intentions are positively influenced by attitude. Likewise, Nordin [74] specified that attitude is a key essential factor for individuals’ intentions to become green entrepreneurs.

Another internal factor that may impact the intention of green entrepreneurship among higher education students is green consumption commitment. The results show that it has strong positive effect on Saudi students’ intentions concerning green entrepreneurship. Thus, our hypothesis (H2) is supported. That is, students with a high level of concern regarding environmental outcomes will have more interest in having green consumption performance [75]. These results are in accordance with prior work from [76], who reported that the perception of environmental concern is the central cause for implementing green consumption practices, and [77,78], who specified that persons with great environmental anxieties are enthusiastic to provide additional green products/services. Our results are also comparable to those of Amankwah and Sesen [23] who showed that students who recognize the importance of protecting the environment are more inspired to be involved in green entrepreneurship.

Finally, entrepreneurial self-efficacy is reported to have a favorable and significant influence on Saudi students’ green entrepreneurship intentions, hence supporting our hypothesis (H3). Our results lend support to earlier evidence, such as [71,79]. They argued that, in terms of intentions toward entrepreneurship, university students own robust self-confidence that may have an advantageous outcome on their observed behavioral control. Further, the association between students’ self-efficacy and their intention concerning green entrepreneurship is comparable to that documented by Soomro et al. [18] and Alvarez-Risco et al. [24]. Similarly, Nordin [74] identified that self-efficacy is one of the essential factors that impact individual awareness to become a green entrepreneur. Likewise, many prior studies (i.e., Prabowo et al. [80], Esfandiar et al. [81], and Nowiński et al. [82]) reported the positive impact of self-efficacy on the growth of a person’s entrepreneurial intentions to create his/her own business. Indeed, our results enhance the outcomes of Autio et al. [12] which reveal that self-efficacy is the most notable element in examining entrepreneurial intentions.

Regarding the external antecedents, it was found that subjective norms have a negative and significant association with green entrepreneurship intentions. That is, hypothesis (H4) is not accepted. This result means that the perceived social pressure and norms from family and friends failed to positively impact the desire of university students to be involved in green entrepreneurial practices. These results contradict what was reported by [11,42,83], who confirmed the positive impact of subjective norms on entrepreneurial intentions. Our reported results are in line with those of Autio et al. [12] and Al-Jubari [13], who found the entrepreneurial intentions of graduate business students to be negatively impacted by subjective norms. In fact, these negative results are common in the preceding literature (i.e., Alam et al. [84] and Majeed et al. [85]), which established that subjective norms could not predict entrepreneurial intentions. When entrepreneurs obtain support from their relatives, friends, and colleagues or they have conservative confidence in green entrepreneurship as a business choice, they are more expected to think about doing green entrepreneurship [20]. These results showed that, despite recent efforts exerted by the KSA government to promote entrepreneurship and diversify the economy, many students may still face cultural and societal barriers that limit their ability and willingness to pursue entrepreneurship. In Saudi culture, there is a strong emphasis on job security and stability, with many students encouraged to pursue careers in established industries or the public sector. This can discourage students from considering entrepreneurship as a viable career option, as it is often perceived as a high-risk and uncertain path. Additionally, in Saudi culture, there is a strong emphasis on personal reputation and image, and failure can be seen as a personal flaw or weakness. This stigma can be a significant barrier for students who may be hesitant to take the risks associated with entrepreneurship for fear of failure and negative judgment from their peers and families.

In terms of the fifth hypothesis (H5), our reported results indicate that country support has a positive influence on the intention for green entrepreneurship of students in Saudi universities; hence, the hypothesis is accepted. These findings are in accordance with [9] who indicated that the Saudi government encourages the practices of entrepreneurship and help graduates in many universities in constructing their own businesses with the aim of alleviating the problem of youth unemployment. Our results are also similar to those of Ead et al. [86] who pointed out that government support has a positive and substantial influence on green entrepreneurship intentions. Furthermore, Arrighetti et al. [87] and Pérez-Macías et al. [88] reported comparable results about the impact of economic bodies on students’ or youth’s entrepreneurial intentions. On the contrary, Hassan et al. [89] stated that the support of government policies did not impact the inspiration of students to become entrepreneurs. In the case of Saudi Arabia, the support from the government enables students to follow self-employment instead of looking for employment in the public sector. Therefore, entrepreneurship is one important factor in the national agenda of Saudi Arabia [45]. The results also indicate that country support leads to inspiring, motivating, and improving the capability of university students to develop a robust awareness about green entrepreneurship. Particularly, green entrepreneurship entails additional technology, specifically green technology, apart from more financial support which constitutes a key assurance for green entrepreneurs [70]. To this end, to inspire new green entrepreneurs, country support may include adjusting specific regulations and enhancing financial institutions to support ventures in green businesses via certain loans at rational interest rates [24].

The variable related to university education support was found to have a positive and significant connection with green entrepreneurship intentions among Saudi students. Hence, hypothesis (H6) is supported. Our findings are in line with prior work (i.e., [9,78,90]) who reported a favorable connection between the support provided by university and the intention of students to become entrepreneurs. Further, the results are in agreement with a recent study from Ead et al. [86] who found that education support has a strong and positive influence on green entrepreneurship intentions. Moreover, the results of Nordin [74] suggest that education has an influential role as a factor of interest for individuals wanting to become green entrepreneurs. In the same vein, the results of Souitaris et al. [91], Karimi et al. [92], Arrighetti et al. [87], and Pérez-Macías et al. [88] specified that educational programs outstandingly improved students’ entrepreneurial intentions. The results further lend support to the notion of the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Our results are also in line with the fact that the a greater part of startups in Saudi Arabia were established by university graduates [93]. According to these results, the green entrepreneurship intention of students was enhanced when they received support through university education. That is, universities construct awareness and motivate education of applied knowledge, thus students have the mechanisms to start their own companies. This will lead to decreasing unemployment rates, specifically in countries that may have graduate students who are facing difficulties in getting jobs. Further, the results are attributed to the fact that education can change the attitudes of students and impact their possible career tracks, in addition to having a key long-term outcome on their entrepreneurial mentality [94,95]. Thus, university education support should prepare students for suitable businesses by delivering programs, training, and incentives to produce green entrepreneurs who are able to build their businesses to provide green products [96].

The above results indicate that the connection with internal antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions is stronger than that of external antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions. Green consumption commitment, self-efficacy, and attitude towards green entrepreneurship are more strongly associated with entrepreneurship intentions than external factors such as subjective norms, university, and country support. This implies that, while access to funding and resources can be a significant factor in enabling entrepreneurship, it may not be as critical as an individual’s personality or inherited attitudes in driving their decision to become an entrepreneur. Therefore, policymakers and educators who aim to promote entrepreneurship should focus on developing and nurturing these internal antecedents in individuals, rather than relying solely on external factors to drive entrepreneurship intentions.

Furthermore, the above results give evidence that some individuals seem to have an inherent inclination towards environmentalism and sustainable business practices, which manifests as a passion for green entrepreneurship. These individuals may be described as being “born to be green entrepreneurs.” Such individuals tend to possess certain internal and inherited traits that make them more likely to pursue green entrepreneurship. For example, they may have a deep-seated sense of green consumption commitment and a desire to make a positive impact towards the environment. Green entrepreneurs with high levels of self-efficacy tend to be more resilient in the face of challenges and setbacks, and they are more likely to persist in pursuing their goals. They also tend to have greater self-awareness and a clearer understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, which allows them to make more informed decisions and take calculated risks. Green entrepreneurs with a positive attitude tend to be more innovative, resourceful, and flexible in their approach to business, and they are more likely to identify new opportunities for growth and development. While external factors, such as university support, country support, and subjective norms can certainly contribute to an individual’s success as a green entrepreneur, it is often their internal and inherited traits that set them apart from others. These traits provide them with the passion, drive, and vision necessary to create and sustain successful environmentally sustainable businesses.

7. Conclusions and Implications

Currently, entrepreneurs have greater awareness of constructing businesses that can achieve profits and engage with communities while certifying that managing these businesses has no harmful influence on the environment; entrepreneurs can achieve this through green entrepreneurial companies. Therefore, universities, regulators, and company directors need to enhance their awareness of green entrepreneurship intentions and fully understand its relevant antecedents with the aim to support them by reforming education programs. Thus, the purpose of this study is to examine the impact of internal antecedents (self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption commitment) and external antecedents (country support, university support, and subjective norms) on green entrepreneurship intentions among higher education students. According to the results of our analysis, we can draw the following conclusions: Regarding internal antecedents, it was found that self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption commitment are positively and significantly related to green entrepreneurship intentions. In terms of external antecedents, the results show that country support and university support have a positive and strong impact on green entrepreneurship intentions. In contrast, subjective norms have a negative association with green entrepreneurship intentions. It is also reported that internal antecedents have a greater significant predictive influence than external antecedents. Further, the findings of our study indicate that the TPB can predict and clarify the intentions for green entrepreneurship. It is concluded that Saudi university students have an increased intention to become green entrepreneurs.

Implications of the Study

This study has theoretical implications as well as practical implications. Theoretically, few studies on the intention for green entrepreneurship have been completed; consequently, the current study delivers a reference for Saudi Arabia and other similar countries. Further, Saudi Arabia is currently considered an entrepreneurial center, and its young individuals are showing great awareness and getting involved in small businesses. However, little is acknowledged concerning green entrepreneurial intentions specifically in younger generations (students). Thus, our study contributes to bridge the current gap in the literature. As a novel contribution, our model incorporated comprehensive internal (self-efficacy, attitude, and green consumption commitment) and external (country support, university support, and subjective norms) antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions in higher education students. These antecedents may establish benchmarks for implementing an approach to expand green entrepreneurship capabilities among students. Furthermore, the results of our study contribute to the TPB. It develops and extends the model of TPB by incorporating internal and external suggested determinants of green entrepreneurship intentions. Our results provide support to the postulation of TPB in a developing country such as Saudi Arabia. To this end, our results add to the emergent literature concerning students’ intentions toward green entrepreneurship and how this perception of green can be encouraged among university students.

On the practical implications front, the findings of the current study may provide some guidelines for regulators and policymakers regarding the advancement of green entrepreneurship intentions among university students. For instance, policymakers may enhance or launch more organizations that aim to support green entrepreneurship, eliminate obstacles, and increase access to financial services with the purpose of supporting young entrepreneurs. As our results show that country support has a positive and strong impact on green entrepreneurship intentions, governments should enhance efforts to arrange adequate infrastructure and guidelines that enhance the possibilities of entrepreneurship as an encouraging career alternative. Further, educational support and country support are found to significantly increase green entrepreneurship intentions. Thus, public institutions and universities need to collaborate equally to improve incubator organizations to build pioneering young entrepreneurs. As the relationship between subjective norms and green entrepreneurship intentions is found to be negative, universities are expected to adopt student-centered learning methods in entrepreneurial courses; Ismail et al. [97] claimed that this teaching technique involves applying real-life functional education to study programs aiming to produce entrepreneurs. Student-centered approaches include empirical education by doing. They lead to a constructive influence on students’ personal and professional improvement. It could enhance student engagement in practices such as starting small businesses. Accordingly, the student’s mental development is crucial. Consequently, it is proposed that educational approaches and contents specifically planned to develop subjective norms are incorporated into entrepreneurship education programs. Subjective norms can be enhanced by tools of teamwork and by offering opportunities for students to build a connection with entrepreneurial-minded groups and peers.

Additionally, governments may place financial requirements for universities to dynamically integrate green entrepreneurship into their academic programs and courses. That is, universities have an imperative role in boosting their students’ engagement in green entrepreneurial businesses and activities. Students, as young entrepreneurs, would then have clear objectives to become entrepreneurs and begin their private businesses, in addition to being capable of controlling the progression and processes of entrepreneurship. Therefore, training workshops, seminars, financial support, advice, and development courses should be delivered by universities to prepare students for green entrepreneurship. This can be completed by launching a specific supporting unit or center in universities. The results of this study may attract the consideration of universities in terms of knowing the antecedents that impact the students’ intentions toward green entrepreneurship, so that they can adopt course contents, construct suitable development programs, and provide funds to support green initiatives. The students’ green entrepreneurial creativeness and green intellectual capability should be improved.

8. Limitation and Future Research Directions

Although the current study delivers various insights, it also has several limitations. First, this study was carried out on students in King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia. Consequently, to generalize the results to other universities in Saudi Arabia or other countries, results must be investigated further. Thus, future studies may extend the university student group to be surveyed to include more universities and countries; a comparative study could also be carried out. Second, the sample of our study was from an academic setting. Hence, further studies may examine the antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions among youth outside the universities. Third, the use of a cross-sectional research design limits the ability to establish causality and infer temporal relationships between variables. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether the identified antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention are the cause or effect of such an intention. A longitudinal research design could provide more robust evidence of causality and temporal relationships, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics underlying green entrepreneurship intentions among higher education students. Fourth, future studies could examine additional antecedents of green entrepreneurship, such as the behavior of green citizenship and green interpersonal behavior. Lastly, as a venue for future work, it is imperative to study the interaction and interrelationships between all independent variables (antecedents of GII) and test the role of more moderating and mediating variables on the association between internal antecedents, external antecedents, and green entrepreneurship intention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E., M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; methodology, I.A.E.; software, I.A.E.; validation,, M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; formal analysis, I.A.E.; investigation, M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; data curation, I.A.E. and M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; visualization, I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration,., M.A.S.A. and M.A.A.; funding acquisition, M.A.S.A. and M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the deputyship of Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research through project number INST074.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: INST074, date of approval: 25 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, Y.; Tsai, S.-B.; Zhang, S.; Li, G. Green Entrepreneurship in Transitional Economies: Breaking through the Constraints of Legitimacy. In Green Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1136–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, G. From Green Entrepreneurial Intentions to Green Entrepreneurial Behaviors: The Role of University Entrepreneurial Support and External Institutional Support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, G.A.; Anghel, M.A. Green Entrepreneurship among Students—Social and Behavioral Motivation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakid, W.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. The Influence of Green Entrepreneurship on Sustainable Development in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Formal Institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, M.; Hansen, T.; Heiberg, J.; Klitkou, A.; Steen, M. Green Growth–A Synthesis of Scientific Findings. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, R.; Hassan, R.A. The Role of Opportunities for Green Entrepreneurship Towards Investigating the Practice of Green Entrepreneurship among SMEs in Malaysia. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2019, 8, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y. Green Entrepreneurial Orientation and Green Innovation: The Mediating Effect of Supply Chain Learning. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244019898798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Fathi, M.R.; Hassani, N.S. Eco-Innovation and Cleaner Production as Sustainable Competitive Advantage Antecedents: The Mediating Role of Green Performance. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2020, 22, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.; You, X.; Wang, H.-P.; Wang, B.; Lai, W.-Y.; Su, N. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, S. The Influence of Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perception of Self-Control And Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Behav. Entrep. 2020, 4, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, R.H.; Klofsten, M.; Parker, G.G.C.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial Intent among Students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I. College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: Testing an Integrated Model of SDT and TPB. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019853467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Zhuo, C.; Mou, Y.; Pu, Z.; Zhou, Y. COVID-19 to Green Entrepreneurial Intention: Role of Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Optimism, Ecological Values, Social Responsibility, and Green Entrepreneurial Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 732904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazz, A.M.S.; Elshaer, I.A. Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, Entrepreneurial Resilience and Creative Performance with the Mediating Role of Institutional Orientation: A Quantitative Investigation Using Structural Equation Modeling. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Ghumro, I.A.; Shah, N. Green Entrepreneurship Inclination among the Younger Generation: An Avenue towards a Green Economy. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Loarne Lemaire, S.; Razgallah, M.; Maalaoui, A.; Kraus, S. Becoming a Green Entrepreneur: An Advanced Entrepreneurial Cognition Model Based on a Practiced-Based Approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 801–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.; Pham, N.A.N.; Nguyen, T.K.N.; Nguyen, N.K.V.; Ngo, H.T.; Pham, T.T.L. Factors Affecting Green Entrepreneurship Intentions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, H.; Chung, J.; Thorndike Pysarchik, D. Antecedents to New Food Product Purchasing Behavior among Innovator Groups in India. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The Effect of Green Human Resource Management on Hotel Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Environmental Performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, J.; Sesen, H. On the Relation between Green Entrepreneurship Intention and Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; García-Ibarra, V.; Rosen, M.A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Factors Affecting Green Entrepreneurship Intentions in Business University Students in COVID-19 Pandemic Times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Gutiérrez, P.I.; Pastor Pérez, M.D.P.; Alonso Galicia, P.E. University Entrepreneurship: How to Trigger Entrepreneurial Intent of Undergraduate Students. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 927–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutzler, J.; Andonova, V.; Diaz-Serrano, L. How Context Shapes Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as a Driver of Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Multilevel Approach. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 880–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robayo-Acuña, P.V.; Martinez-Toro, G.-M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Rojas-Osorio, M. Intention of Green Entrepreneurship Among University Students in Colombia. In Footprint and Entrepreneurship: Global Green Initiatives; Alvarez-Risco, A., Muthu, S.S., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., Eds.; Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 259–272. ISBN 978-981-19889-5-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, D.F.; Dean, T.J.; Payne, D.S. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Dimov, D. The Call of the Whole in Understanding the Development of Sustainable Ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, W.R.; Pacheco, D.F.; York, J.G. The Impact of Social Norms on Entrepreneurial Action: Evidence from the Environmental Entrepreneurship Context. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Grilo, I.; Thurik, A.R. Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, D.; Bruton, G.D. Rapid Institutional Shifts and the Co–Evolution of Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, K.; Saladrigues, R. Impact of Attitude towards Entrepreneurship Education and Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, P.H.; Solomon, G.T.; Weaver, K.M. Entrepreneurial Selection and Success: Does Education Matter? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnadi, M.; Gheith, M.H. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in Higher Education: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Song, Y.; Pan, B. How University Entrepreneurship Support Affects College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallatah, M.I.; Ayed, T.L. “Entrepreneurizing” College Programs to Increase Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Mediation Framework. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.; Yani-de-Soriano, M.; Muffatto, M. The Role of Perceived University Support in the Formation of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. In Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-315-61149-5. [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, W.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A.; Qureshi, M.A. Impact of Personality Traits and University Green Entrepreneurial Support on Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Moderating Role of Environmental Values. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 13, 1154–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, J.; Khan, M.A.S.; Jin, S.; Altaf, M.; Anwar, F.; Sharif, I. Effects of Subjective Norms and Environmental Mechanism on Green Purchase Behavior: An Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Nazir, M.; Hashmi, S.B.; Di Vaio, A.; Shaheen, I.; Waseem, M.A.; Arshad, A. Green and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Mediation-Moderation Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, C.W. Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behaviour, Entrepreneurship Education and Self Efficacy toward Entrepreneurial Intention University Student in Indonesia; Universitas Ciputra: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Noor, N.H.; Yaacob, M.; Omar, N. Redefining the Link between Subjective Norm and Entrepreneurship Intention: Mediating Effect of Locus of Control. J. Int. Bus. Econ. Entrep. (JIBE) 2021, 6, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Saudi Green Initiatives. Available online: https://www.greeninitiatives.gov.sa/about-sgi/ (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and Cross–Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Wang, S.-M. Social Entrepreneurial Intentions and Its Influential Factors: A Comparison of Students in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002) Perceived Behavioural Control, Self-efficacy, Locus of Control and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Barreto, K.; Zuñiga-Jara, S.; Ruiz-Campo, S. Determinantes de la intención emprendedora: Nueva evidencia. Determ. Entrep. Intent. New Evid. 2016, 41, 325–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.A. Personal Traits and Digital Entrepreneurship: A Mediation Model Using SmartPLS Data Analysis. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Younis, N.S. Born Not Made: The Impact of Six Entrepreneurial Personality Dimensions on Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence from Healthcare Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. The Impact of Gender on the Link between Personality Traits and Entrepreneurial Intention: Implications for Sustainable Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. I Think I Can, I Think I Can: Effects of Entrepreneurship Orientation on Entrepreneurship Intention of Saudi Agriculture and Food Sciences Graduates. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Entrepreneurial Resilience and Business Continuity in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry: The Role of Adaptive Performance and Institutional Orientation. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monecke, A.; Leisch, F. SemPLS: Structural Equation Modeling Using Partial Least Squares; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for Common Method Variance in Cross-Sectional Research Designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS Release 10 for Windows: A Guide for Social Dcientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3. Baskı); Guilford: New York NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; p. xiv, 103. ISBN 978-0-9622628-4-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, Y. Factors That Can Promote the Green Entrepreneurial Intention of College Students: A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, M.B.A.; Salim, M.; Kamarudin, H. The Relationship between Educational Support and Entrepreneurial Intentions in Malaysian Higher Learning Institution. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 69, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, M.; Kassim, N.M.; Zain, M. Inclinations of Saudi Arabian and Malaysian Students towards Entrepreneurship. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2018, 11, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gird, A.; Bagraim, J.J. The Theory of Planned Behaviour as Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intent amongst Final-Year University Students. South Afr. J. Psychol. 2008, 38, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N. Green Entrepreneurial Intention of Mba Students: A Malaysian Study. Int. J. Ind. Manag. 2020, 5, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, I.; Phau, I. Attitudes towards Environmentally Friendly Products: The Influence of Ecoliteracy, Interpersonal Influence and Value Orientation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Lin, Y.-P.; Gao, Y.-S. Measuring Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship Capabilities: The Case of Taiwan Science Parks. J. Knowl. Econ. 2012, 3, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M.; Suki, N.M. Determining Students’ Behavioural Intention to Use Animation and Storytelling Applying the UTAUT Model: The Moderating Roles of Gender and Experience Level. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Ameen, F.A.; Fayyad, S. Sustainable Horticulture Practices to Predict Consumer Attitudes towards Green Hotel Visit Intention: Moderating the Role of an Environmental Gardening Identity. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do Entrepreneurship Programmes Raise Entrepreneurial Intention of Science and Engineering Students? The Effect of Learning, Inspiration and Resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, H.; Ikhsan, R.B.; Yuniarty, Y. Drivers of Green Entrepreneurial Intention: Why Does Sustainability Awareness Matter among University Students? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M.; Pratt, S.; Altinay, L. Understanding Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Developed Integrated Structural Model Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Gender on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in the Visegrad Countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Tornikoski, E.T. Predicting Entrepreneurial Behaviour: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Kousar, S.; Rehman, C.A. Role of Entrepreneurial Motivation on Entrepreneurial Intentions and Behaviour: Theory of Planned Behaviour Extension on Engineering Students in Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Ghumman, A.R.; Abbas, Q.; Ahmad, Z. Role of Entrepreneurial Passion between Entrepreneurial Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Entrepreneurial Intention: Measuring the Entrepreneurial Behavior of Pakistani Students. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2021, 15, 636–662. [Google Scholar]

- Ead, H.A.; Rashed, A.; Ghoniem, W.; Turk, M. Factors Affecting Students’ Intentions toward Green Entrepreneurship in COVID-19 Pandemic Times: A Case Study of Egyptian Universities. Int. J. Educ. Learn. 2022, 4, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighetti, A.; Caricati, L.; Landini, F.; Monacelli, N. Entrepreneurial Intention in the Time of Crisis: A Field Study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 835–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Macías, N.; Fernández-Fernández, J.-L.; Rúa Vieites, A. The Impact of Network Ties, Shared Languages and Shared Visions on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Online University Students. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Anwar, I.; Saleem, A.; Alalyani, W.R.; Saleem, I. Nexus between Entrepreneurship Education, Motivations, and Intention among Indian University Students: The Role of Psychological and Contextual Factors. Ind. High. Educ. 2022, 36, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.A.; Amjed, S.; Jaboob, S. The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship Education in Shaping Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A. Dimensionality Analysis of Entrepreneurial Resilience amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Models with Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: A Study of Iranian Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions and Opportunity Identification. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K.; Edelman, L.F.; Manolova, T.S.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G. When Do Entrepreneurial Intentions Lead to Actions? The Role of National Culture. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, A.; do Paco, A.; Ferreira, J.; Raposo, M.; Gouveia Rodrigues, R. Psychological Characteristics and Entrepreneurial Intentions among Secondary Students. Educ.+Train. 2013, 55, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, S.F.F.B.; Mamun, A.A.; Nawi, N.B.C.; Nasir, N.A.B.M.; Zakaria, M.N.B. Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention and the Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship Education: A Conceptual Model. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 3006–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D. Philanthropy, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: An Introduction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-38016-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.B.; Sawang, S.; Zolin, R. Entrepreneurship Education Pedagogy: Teacher-Student-Centred Paradox. Educ.+Train. 2018, 60, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).