Triple Bottom Line, Sustainability, and Economic Development: What Binds Them Together? A Bibliometric Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Publications and Most Relevant Publications and Journals

3.2. Co-Occurrence Analysis

3.3. Cluster Analysis

4. Discussion

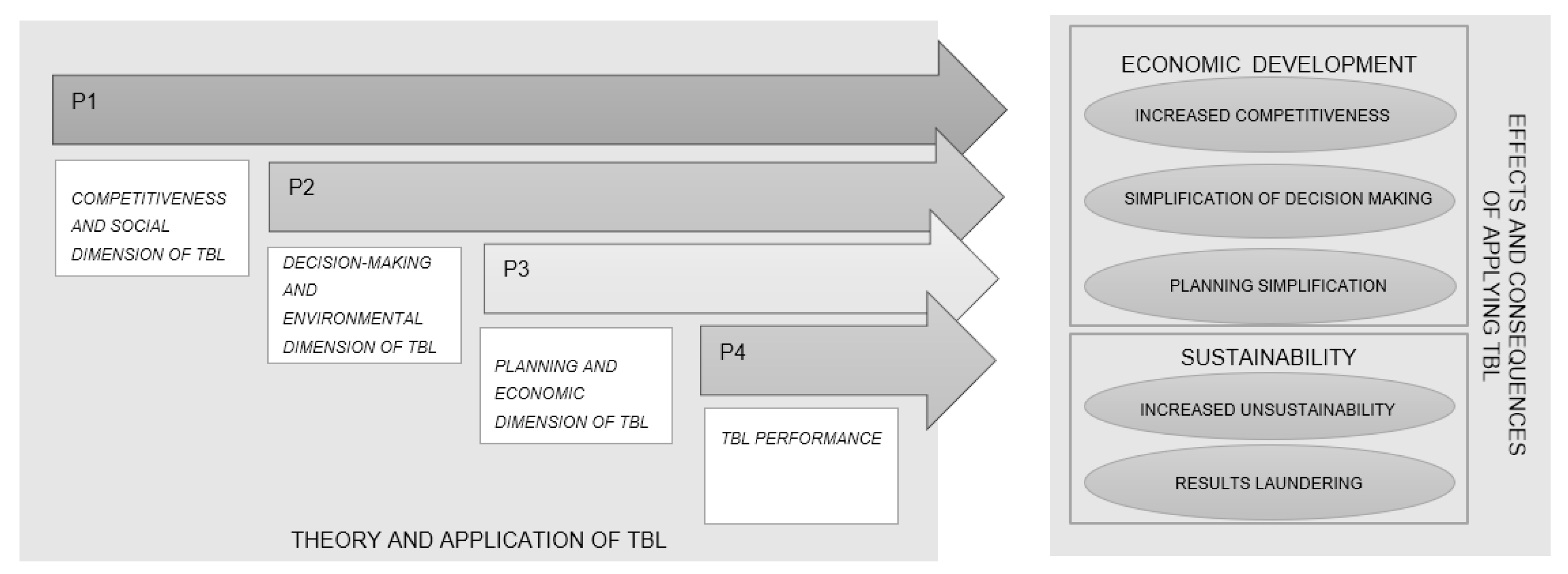

4.1. Cluster Discussion and Conceptual Model

4.1.1. Cluster 1—Competitiveness and Social Dimension of TBL

4.1.2. Cluster 2—Decision Making and Environmental Dimension of TBL

4.1.3. Cluster 3—Planning and Economic Dimension of TBL

4.1.4. Cluster 4—TBL Performance

4.1.5. Future Lines of Research by Cluster

4.1.6. Building the Conceptual Model

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Pratical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; et al. Managing the Health Effects of Climate Change. Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, B.; Barraclough, K.; Sypek, M.; Gois, P.; Arnold, L.; McDonald, S.; Knight, J. A Survey of Environmental Sustainability Practices in Dialysis Facilities in Australia and New Zealand. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, Z.; Arslan, A.; Puhakka, V. Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy, Sustainable Product Attributes, and Export Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1840–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ferrero, J.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B. Effect of Financial Reporting Quality on Sustainability Information Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Roh, T. Open for Green Innovation: From the Perspective of Green Process and Green Consumer Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Lieshout, J.W.F.C.; Nijhof, A.H.J.; Naarding, G.J.W.; Blomme, R.J. Connecting Strategic Orientation, Innovation Strategy, and Corporate Sustainability: A Model for Sustainable Development through Stakeholder Engagement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4068–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döll, L.M.; Ulloa, M.I.C.; Zammar, A.; do Prado, G.F.; Piekarski, C.M. Corporate Venture Capital and Sustainability. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. Green Open Innovation Activities and Green Co-Innovation Performance in Taiwan’s Manufacturing Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Obrenovic, B.; Du, J.; Godinic, D.; Khudaykulov, A. COVID-19 Pandemic Implications for Corporate Sustainability and Society: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Governance for Sustainability. Corp. Gov. An Int. Rev. 2006, 14, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.G. From Plimsoll Line to Triple Bottom Line: Adding Value through Partnership. Bottom Line 2015, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado-Peña, D.; López-Ruiz, V.R.; Alfaro-Navarro, J.L. The Effects of Environmental and Social Dimensions of Sustainability in Response to the Economic Crisis of European Cities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8255–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Q.; Gallear, D.; Ghobadian, A.; Ramanathan, R. Managing Knowledge in Supply Chains: A Catalyst to Triple Bottom Line Sustainability. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Lim, M.K.; Wong, W.P.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhan, Y. A Framework for Evaluating the Performance of Sustainable Service Supply Chain Management under Uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isil, O.; Hernke, M.T. The Triple Bottom Line: A Critical Review from a Transdisciplinary Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper & Bros: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Montabon, F.; Pagell, M.; Wu, Z.H. Making Sustainability Sustainable. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, D.; Muller, J.M.; Arnold, C.; Voigt, K.I. Sustainable industrial value creation: Benefits and challenges of industry 4.0. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1740015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, G. Measuring Organizational Performance: Beyond the Triple Bottom Line. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Bohm, S.; Eatherley, D. Systems Resilience and SME Multilevel Challenges: A Place-Based Conceptualization of the Circular Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.T.; Wang, J.Y. Research on Index Construction of Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Its Impact on Economic Growth. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A.; Gonzalez-Padron, T.L. The Structure of Sustainability Research in Marketing, 1958-2008: A Basis for Future Research Opportunities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.J.; Gray, R. W(h)Ither Ecology? The Triple Bottom Line, the Global Reporting Initiative, and Corporate Sustainability Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.; Yalcin, M.G.; Hales, D.N.; Kwon, H.Y. Interactions in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Framework Review. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 140–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, K.; Hays, C.; Center, H.; Daley, C. Building Capacity and Sustainable Prevention Innovations: A Sustainability Planning Model. Eval. Program. Plann. 2004, 27, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroun, W.; Ecim, D.; Cerbone, D. Refining Integrated Thinking. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, M.S.; Wang, J.L.; Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Iqbal, M.; Ismail, M. Establishing a Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation Model for Promoting Sustainability in the Food Sector: A Hybrid Approach of Expert Mining and ISM-MICMAC. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 8851–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, K.; Berwa, A. Sustainable Competitiveness: Redefining the Future with Technology and Innovation. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2017, 7, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.P.; Stead, J.G.; Stead, E. The Global Pricing of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 11, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, N.; Ha, N.C.; Ghazali, E.M. Bridging the Gap between Branding and Sustainability by Fostering Brand Credibility and Brand Attachment in Travellers ’ Hotel Choice. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 308–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajnef, K.; Ellouz, S. Nonlinear Causality between CSR and Firm Performance Using NARX Model: Evidence from France. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.; Pivo, G. The Triple Bottom Line and Sustainable Economic Development Theory and Practice. Econ. Dev. Q. 2017, 31, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, K.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z. All for One or All for Three: Empirical Evidence of Paradox Theory in the Triple-Bottom-Line. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaimani, S.; Sedighi, M. Toward a Holistic View on Lean Sustainable Construction: A Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Surface, D.L.; Zhang, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Practices in B2B Markets: A Review and Research Agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 106, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.J.; Lee, I.T. An Empirical Study on the Manufacturing Firm’s Strategic Choice for Sustainability in SMEs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J. Sustainability and Business Outcomes in the Context of SMEs: Comparing Family Firms vs. Non-Family Firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muhammad Suandi, M.E.; Amlus, M.H.; Hemdi, A.R.; Abd Rahim, S.Z.; Ghazali, M.F.; Rahim, N.L. A Review on Sustainability Characteristics Development for Wooden Furniture Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagranda, Y.G.; Wiśniewska-Paluszak, J.; Paluszak, G.; Mores, G.d.V.; Moro, L.D.; Malafaia, G.C.; Azevedo, D.B.d.; Zhang, D. Emergent Research Themes on Sustainability in the Beef Cattle Industry in Brazil: An Integrative Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, T.B.; Phadke, S.; Nair, M.V.; Flanagan, D.J. Examination of Sustainability Goals: A Comparative Study of US and Indian Firms. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 28, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzschbach, J.; Tanikulova, P.; Lueg, R. The Role of Top Managers in Implementing Corporate Sustainability—A Systematic Literature Review on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nadae, J.; Carvalho, M.M.; Vieira, D.R.; Nadae, J.; Carvalho, M.M.; Vieira, D.R.; de Nadae, J.; Carvalho, M.M.; Vieira, D.R. Integrated Management Systems as a Driver of Sustainability Performance: Exploring Evidence from Multiple-Case Studies. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2021, 38, 800–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Albareda, L.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Seuring, S. Traceability for Sustainability—Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bai, E.; Liu, L.; Wei, W. A Framework of Sustainable Service Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milojevic, S.; Sugimoto, C.R.; Yan, E.J.; Ding, Y. The Cognitive Structure of Library and Information Science: Analysis of Article Title Words. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1933–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W.; Yuan, L.; Ji, G.D.; Liu, Y.S.; Cai, Z.; Chen, X. A Bibliometric Review on Carbon Cycling Research during 1993–2013. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 6065–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Liu, W.; Dunford, M. Visualizing the Intellectual Structure and Evolution of Innovation Systems Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 103, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, S.; Faria, L.G.D.; Jurowetzki, R. Unveiling Scientific Communities about Sustainability and Innovation. A Bibliometric Journey around Sustainable Terms. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thirumaran, K.; Jang, H.J.; Pourabedin, Z.; Wood, J. The Role of Social Media in the Luxury Tourism Business: A Research Review and Trajectory Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-Based Clustering of Publications Using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veloutsou, C.; Ruiz, C. Brands as Relationship Builders in the Virtual World: A Bibliometric Analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 39, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.L. A New Bibliographic Coupling Measure with Descriptive Capability. Scientometrics 2017, 110, 915–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M.M. Bibliographic Coupling Between Scientific Papers. Am. Doc. 1963, 14, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.K.; Phipps, M.; Weaver, T.; Carrington, M.; Luchs, M.; Catlin, J.; Gupta, S.; Santos, N.; Scott, K.; Williams, J. Managing the Tensions at the [Intersection of the Triple Bottom Line: A Paradox Theory Approach to Sustainabillity Management. J. Public. Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Performance: Analysis of Triple Bottom Line Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.T.; Wang, J.Y.; Hua, X.Y.; Liu, Z.D. Entrepreneurship and High-Quality Economic Development: Based on the Triple Bottom Line of Sustainable Development. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Troise, C.; Strazzullo, S.; Bresciani, S. Creating Shared Value through Open Innovation Approaches: Opportunities and Challenges for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, N.; Pokharel, M.P. How Sustainability Is Reflected in the S&P 500 Companies’ Strategic Documents. Organ. Environ. 2017, 30, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Siddique, M.; Ali, K. Responsible Leadership and Business Sustainability: Exploring the Role of Corporate Social Responsibility and Managerial Discretion. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2022, 127, 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattera, M.; Ruiz-Morales, C.A. UNGC Principles and SDGs: Perception and Business Implementation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassala, C.; Orero-Blat, M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. The Financial Performance of Listed Companies in Pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Econ. Res. Istraz. 2021, 34, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, I.; Hasnaoui, A. The Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Vision of Four Nations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, K.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Is It Rewarded by the Corporate Bond Market? A Critical Note. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Warnick, B.J. Should We Require Every New Venture to Be a Hybrid Organization? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 630–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M.R.; Diaz-Fernandez, M.C.; Simonetti, B. The Social, Economic and Environmental Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role Played by Consumers and Potential Entrepreneurs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Farooq, K. Green Capabilities, Green Purchasing, and Triple Bottom Line Performance: Leading toward Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixell, M.J.; Luoma, P. Stakeholder Pressure in Sustainable Supply Chain Management A Systematic Review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Hamid, A.A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Supply Chain Resilience Strategies and Their Impact on Sustainability: An Investigation from the Automobile Sector. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layaoen, H.D.Z.; Abareshi, A.; Dan-Asabe, A.M.; Abbasi, B. Sustainability of Transport and Logistics Companies: An Empirical Evidence from a Developing Country. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, P.; Seuring, S. Putting Sustainability into Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M. Corporate Social Sustainability in Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review. J. Glob. Responsib. 2020, 11, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Khan, S.A.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Naim, I. Sustainable Warehouse Evaluation with AHPSort Traffic Light Visualisation and Post-Optimal Analysis Method. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2022, 73, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde-Calonge, A.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Saez-Martinez, F.J. The Circularity of the Business Model and the Performance of Bioeconomy Firms: An Interactionist Business-Environment Model. COGENT Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2140745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P. Do Internal and External Environmental Management Contribute to the Triple Bottom Line? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chen, H.Z.; Hazen, B.T.; Kaur, S.; Gonzalez, E. Circular Economy and Big Data Analytics: A Stakeholder Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P.; Zaccour, G. A Two-Period Game of a Closed-Loop Supply Chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 232, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.; Zeng, W.J.; Tse, Y.K.; Wang, Y.C.; Smart, P. Examining the Antecedents and Consequences of Green Product Innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Hahn, R.; Seuring, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in “Base of the Pyramid” Food Projects-A Path to Triple Bottom Line Approaches for Multinationals? Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardi, A.A.; Mahdiraji, H.A.; Masoumi, S.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. Developing Sustainable Competitive Advantages from the Lens of Resource-Based View: Evidence from IT Sector of an Emerging Economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.; Boulaksil, Y.; Qian, Y.G.; Allaoui, H. Modelling and Analysis of Online Ride-Sharing Platforms—A Sustainability Perspective. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 304, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.T.; Yang, Z.L. Drivers of Green Innovation in BRICS Countries: Exploring Tripple Bottom Line Theory. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Mion, G.; Brunetti, F.; Vargas-Sanchez, A. The Contribution of Manufacturing Companies to the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals: An Empirical Analysis of the Operationalization of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. Key Factors of Sustainability in Project Management Context: A Survey Exploring the Project Managers’ Perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Singh, R.K. Outsourcing and Reverse Supply Chain Performance: A Triple Bottom Line Approach. Benchmarking-An Int. J. 2021, 28, 1146–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.; Langella, I.; Carbo, J. From Green to Sustainability: Information Technology and an Integrated Sustainability Framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksson, J.; Wise, N.; Scott, P. Iceland’s Bourgeoning Cruise Industry: An Economic Opportunity or a Local Threat? Local Econ. 2020, 35, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Farrell, P.; Al-edenat, M. The Impact of Project Sustainability Management (PSM) on Project Success A Systematic Literature Review. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, A.T.; Panizzolo, R. Metrics for Measuring Industrial Sustainability Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Azmi, A.; Majid, R.A. Strategic direction of information technology on sustainable supply chain practices: Exploratory case study on fashion industry in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 23, 518–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foran, B.; Lenzen, M.; Dey, C.; Bilek, M. Integrating Sustainable Chain Management with Triple Bottom Line Accounting. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgeman, R.; Eskildsen, J. Modeling and Assessing Sustainable Enterprise Excellence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perello-Marin, M.R.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, R.; Alfaro-Saiz, J.J. Analysing GRI Reports for the Disclosure of SDG Contribution in European Car Manufacturers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 181, 121744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, W.; MacDonald, C. Getting to the Bottom of “Triple Bottom Line”. Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ullah, Z. Sustainable Product Attributes and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Marketing Resource Intensity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4107–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Gh, Z.; Bello-Pintado, A. The Effect of Sustainability on New Product Development in Manufacturing-Internal and External Practices. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogbe, C.S.K.; Bamfo, B.A.; Pomegbe, W.W.K. Market orientation and new product success relationship: The role of innovation capability, absorptive capacity, green brand positioning. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D. Sustainable Procurement Drivers for Extended Multi-Tier Context: A Multi-Theoretical Perspective in the Danish Supply Chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 146, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. Supply Chain Sustainability: Learning from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.; Kant, R.; Thakkar, J. Sustainable Performance Assessment of Rail Freight Transportation Using Triple Bottom Line Approach: An Application to Indian Railways. Transp. Policy 2022, 128, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Farrell, P.; Alrousan, M.; Alwardat, S.; Faisal, M. Incorporating Sustainability into Software Projects: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 1339–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.R.; Lin, K.H.; Chen, C.H.; Otero-Neira, C.; Svensson, G. A Framework of Firms’ Business Sustainability Endeavours with Internal and External Stakeholders through Time across Oriental and Occidental Business Contexts. ASIA PACIFIC J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 963–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallencreutz, J.; Deleryd, M.; Fundin, A. Decoding Sustainable Success. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, R.B.; Garvare, R.; Johnson, M. The Crippled Bottom Line—Measuring and Managing Sustainability. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2015, 64, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. Tightening Corporate Governance. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rodenburg, K.; Foti, L.; Pegoraro, A. Are Firms with Better Sustainability Performance More Resilient during Crises? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3354–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R.; Ramirez, E.; Martinez, J.D. Green Marketing Strategies: An Examination of Stakeholders and the Opportunities They Present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Cagliano, R. Sustainable Innovativeness and the Triple Bottom Line: The Role of Organizational Time Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1097–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitsis, A.M.; Chen, I.J. Do Motives Matter? Examining the Relationships between Motives, SSCM Practices and TBL Performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, P.; Reuter, C.; Pibernik, R.; Sichtmann, C.; Bals, L. Purchasing Managers’ Willingness to Pay for Attributes That Constitute Sustainability. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 62, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, L.; Morgan, Y.C.; Zee, S.; Mock, V.E. The Impact of Organizational Culture and Total Quality Management on the Relationship between Green Practices and Sustainability Performance. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, H.J. An Exploratory Analysis of the Project Management and Corporate Sustainability Capabilities for Organizational Success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C. Differences in Sustainable Management Between Four- and Five-Star Hotels Regarding the Perceptions of Three-Pillar Sustainability. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 791–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The Central Role of Human Resource Management in the Search for Sustainable Organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the Role of Human Resource Management in Corporate Sustainability and Social Responsibility: A Multi-Stakeholder, Multidimensional Approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, K.; Nakata, C.; Zhu, Z. Sustainable Innovation and the Triple Bottom-Line: A Market-Based Capabilities and Stakeholder Perspective. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C.; Garvare, R.; Ahmad, N. Including Sustainability in Business Excellence Models. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2011, 22, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mehmood, R. Enterprise Systems: Are We Ready for Future Sustainable Cities. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Svensson, G.; Eriksson, D. Organizational Positioning and Planning of Sustainability Initiatives: Logic and Differentiators. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2018, 31, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allur, E.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O.; Testa, F. Quality and Environmental Management Linkage: A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sartori, S.; Witjes, S.; Campos, L.M.S.S. Sustainability Performance for Brazilian Electricity Power Industry: An Assessment Integrating Social, Economic and Environmental Issues. Energy Policy 2017, 111, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helfaya, A.; Morris, R. Investigating the Factors That Determine the ESG Disclosure Practices in Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar-Diez, E.; Odriozola, M.D. CSR Committees and Their Effect on ESG Performance in UK, France, Germany, and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauer, E.; Wohner, B.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Food Packaging: An Extended Life Cycle Assessment Including Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste and Circularity Assessment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Praticò, F.G.; Giunta, M.; Mistretta, M.; Gulotta, T.M. Energy and Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Pavement Materials and Technologies for Urban Roads. Sustainability 2020, 12, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Junguitu, A.D.; Allur, E. The Adoption of Environmental Management Systems Based on ISO 14001, EMAS, and Alternative Models for SMEs: A Qualitative Empirical Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schebek, L.; Gassmann, A.; Nunweiler, E.; Wellge, S.; Werthen, M. Eco-Factors for International Company Environmental Management Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, C.L.; Hoogenberg, B.J.; Fratostiteanu, C.; Hashmi, H.B.A. The Relation between Environmental Management Systems and Environmental and Financial Performance in Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Future Lines of Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exploration of the influence that sustainable entrepreneurship has on economic growth in various political contexts. | [24] |

| Development of a conceptual model that analyses how circular economy systems and their resiliency build on the combination of business, society, and environmental system value. | [23] | |

| Analysis of approaches to open innovation that aim to co-create value for society and companies. | [63] | |

| Focusing on subjective measures of performance. | [101] | |

| 2 | Study of the mediating/moderator effect of sustainability in developing new products. | [102] |

| Consideration of the dual moderating role of Realized Absorption Capacity and Green Brand Positioning in the connection between Innovation Capacity and New Product Success. | [103] | |

| Examination of the interrelationships of all supply chain entities. | [104] | |

| Including natural scientists, social scientists, civil society, government, and industry in the operations and supply chain study. Analysis of sustainable strategies that help companies survive after COVID-19. | [105] | |

| 3 | Consulting stakeholders and experts to consider other indicators of sustainability. | [106] |

| Inclusion of more performance aspects in the reverse supply chain study. Consideration of other performance parameters related to the circular economy. | [91] | |

| Consideration of multiple stakeholders in measuring project success. | [94] | |

| Increased research into incorporating sustainability into software projects. | [107] | |

| 4 | Test firms’ business sustainability with the developed framework. | [108] |

| Discussion on the redefinition of economic sustainability, focusing on stakeholders’ perceptions and as drivers for sustainable success. | [109] | |

| Strengthening the evidence between the GRI and the SDGs. | [99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogueira, E.; Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. Triple Bottom Line, Sustainability, and Economic Development: What Binds Them Together? A Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086706

Nogueira E, Gomes S, Lopes JM. Triple Bottom Line, Sustainability, and Economic Development: What Binds Them Together? A Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086706

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogueira, Elisabete, Sofia Gomes, and João M. Lopes. 2023. "Triple Bottom Line, Sustainability, and Economic Development: What Binds Them Together? A Bibliometric Approach" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086706