Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

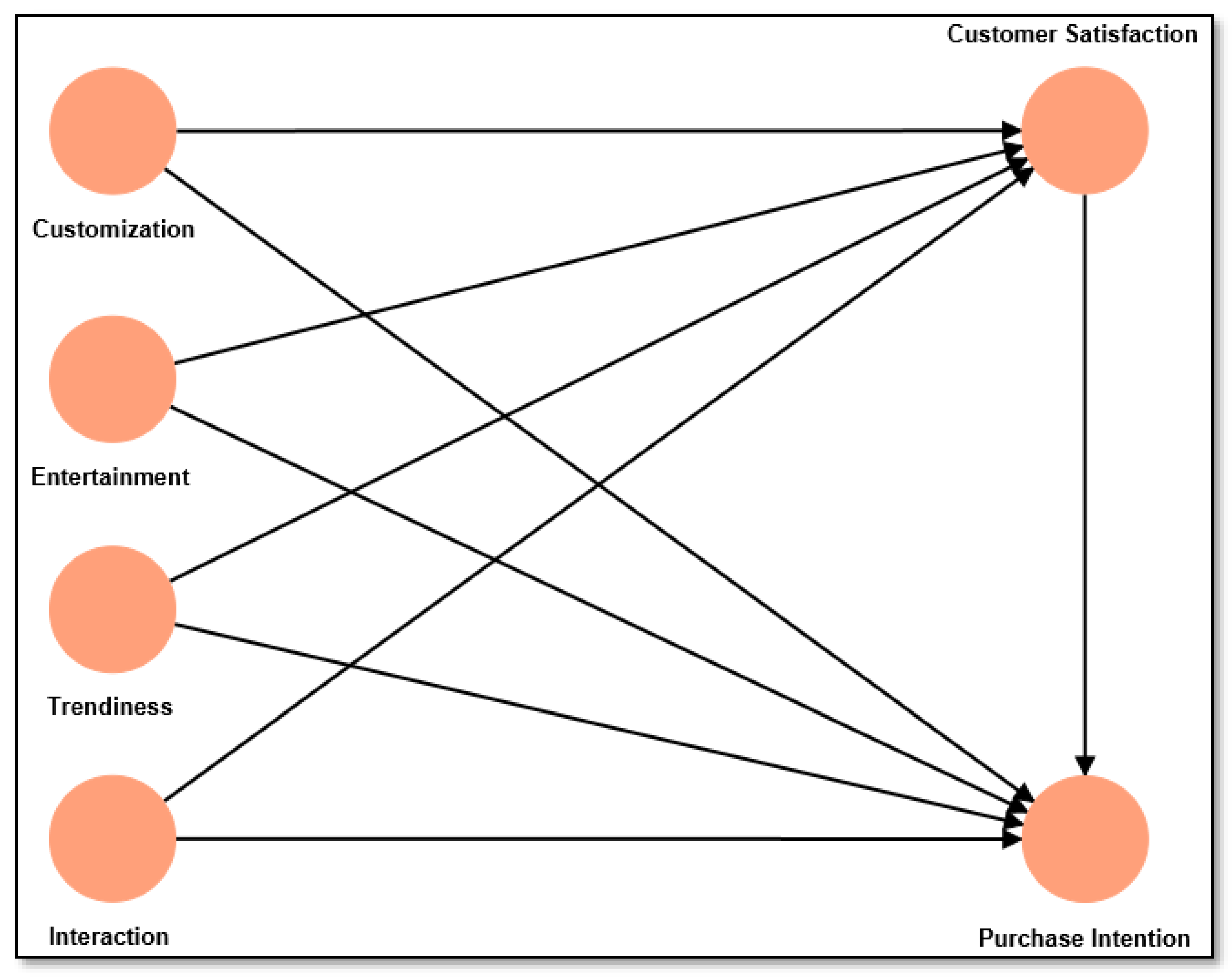

2. An Overview of the Theoretical Background and the Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Social Media Marketing Activities (SMMAs)

2.2. Customer Satisfaction (CS)

2.3. Purchase Intention (PI)

2.4. The Impact of SMMAs on PI

2.5. The Impact of SMMAs on CS

2.6. The Impact of CS on PI

2.7. The Intervening Role of CS in the Relationship between SMMAs and PI

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

3.2. Sample of the Study and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance (CMV)

4.2. Results of Measurement Model Assessment

4.3. Assessment of the Predictive Ability of the Structural Model

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Customization (CUS) | CUST1 | It is possible to search for customized information on restaurant X’s social media |

| CUST2 | Restaurant X’s social media provide lively feed information I am interested in | |

| CUST3 | Restaurant X offers customized services through its social media | |

| Entertainment (ENT) | ENTR1 | The content found in restaurant X’s social media seems interesting. |

| ENTR2 | Utilizing the social media channels of restaurant X is exciting. | |

| ENTR3 | It is fun to collect information on products through restaurant X’s social media. | |

| Trendiness (TRE) | TRND1 | Restaurant X’s social media content is up-to-date |

| TRND2 | Using restaurant X’s social media is very trendy. | |

| TRND3 | The content on restaurant X’s social media is the newest information. | |

| Interaction (INT) | INTR1 | I can easily share my opinions through restaurant X’s social media. |

| INTR2 | It is easy to convey my opinions or conversation with other users through restaurant X’s social media | |

| INTR3 | It is possible to have two-way interaction through restaurant X’s social media. | |

| Customer satisfaction (CS) | CS1 | I am pleased that I have visited this restaurant. |

| CS2 | I really enjoyed myself at this restaurant. | |

| CS3 | Considering all my experiences with this restaurant, my decision to visit it was a wise one. | |

| CS4 | The food quality and services of this restaurant fulfill my expectations. | |

| CS5 | overall, I am satisfied with this restaurant | |

| Purchase Intention (PI) | PI1 | I plan to purchase restaurant products that I have seen on social media. |

| PI2 | I intend to purchase restaurant products that I like based on social media interaction. | |

| PI3 | I am very likely to purchase restaurant products recommended by my friends on social media. |

References

- Manalo, S. Effectiveness of social media marketing in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2020, 9, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choedon, T.; Lee, Y. The effect of social media marketing activities on purchase intention with brand equity and social brand engagement: Empirical evidence from Korean cosmetic firms. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2020, 21, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, K.; Dunnan, L.; Gul, R.F.; Shehzad, M.U.; Gillani, S.H.M.; Awan, F.H. Role of Social Media Marketing Activities in Influencing Customer Intentions: A Perspective of a New Emerging Era. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 808525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepkowska-White, E.; Parsons, A.; Berg, W. Social media marketing management: An application to small restaurants in the US. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Khan, Z.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Social Media Marketing on Apparel Brands’ Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediation of Perceived Value. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 25, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R. An examination of the factors affecting consumer’s purchase decision in the Malaysian retail market. Int. J. Crowd Sci. 2018, 2, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger III, P.J.; De Oliveira, M.J. Driving COBRAs: The power of social media marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yoo, M.; Yang, W. Online Engagement Among Restaurant Customers: The Importance of Enhancing Flow for Social Media Users. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.; Lee, C.; Orth, U.; Kim, C.; Kahle, L. Sustainable marketing and social media: A cross-country analysis of motives for sustainable behaviors. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Sakka, G.; Grandhi, B.; Galati, A.; Siachou, E.; Vrontis, D. Adoption of Social Media Marketing for Sustainable Business Growth of SMEs in Emerging Economies: The Moderating Role of Leadership Support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, H.; Ali Raza, M.; Ali, G.; Aman, J.; Bano, S.; Nurunnabi, M. The effects of corporate social responsibility practices and environmental factors through a moderating role of social media marketing on sustainable performance of business firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navalón, J.G.; Gelashvili, V.; Debasa, F. The Impact of Restaurant Social Media on Environmental Sustainability: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Kiefer, K.; Paul, J. Marketing-to-Millennials: Marketing 4.0, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Law, R.; Wen, I. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepkowska-White, E. Exploring the challenges of incorporating social media marketing strategies in the restaurant business. J. Internet Commer. 2017, 16, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushara, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Albohnayh, A.S.M.; Alshammari, W.G.; Aldoreeb, M.; Elsaed, A.A.; Elsaied, M.A. Power of Social Media Marketing: How Perceived Value Mediates the Impact on Restaurant Followers’ Purchase Intention, Willingness to Pay a Premium Price, and E-WoM? Sustainability 2023, 15, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V.; Sharma, V. The Mediating Role of Customer Relationship on the Social Media Marketing and Purchase Intention Relationship with Special Reference to Luxury Fashion Brands. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 872–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, U.; Baig, S.A.; Hashim, M.; Sami, A. Impact of social media marketing on consumer’s purchase intentions: The mediating role of customer trust. Int. J. Entrep. Res. 2020, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Charni, H.; Khan, S. Impact of Social Media Marketing on Consumer Behavior in Saudi Arabia. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Moslehpour, M.; Ismail, T.; Purba, B.; Wong, W. What makes GO-JEK go in Indonesia? The Influences of social media marketing activities on purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 17, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Impacts of Luxury Fashion Brand’s Social Media Marketing on Customer Relationship and Purchase Intention. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2010, 1, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Malik, G.; Gupta, S. Impact of Extended Marketing Mix of Casual Dining Restaurants on Customer Experience and Customer Satisfaction. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 19155–19161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M. Effectiveness of social media marketing on enhancing performance: Evidence from a casual-dining restaurant setting. Tour. Econ. Bus. Financ. Tour. Recreat. 2021, 27, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Crews, T.B.; Gustafson, C.; Strick, S. Use of Social Networking Sites in the Restaurant Industry: Best Practices. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2012, 15, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-Long, S.; Wongsurawat, W. Social media marketing evaluation using social network comments as an indicator for identifying consumer purchasing decision effectiveness. J. Direct Data Digit. Mark. Pract. 2015, 17, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.J.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.J. The Effect of Social Media Usage Characteristics on e-WOM, Trust, and Brand Equity: Focusing on Users of Airline Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K. An empirical study the effect of social media marketing activities upon customer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth and commitment in indemnity insurance service. In Proceedings of the International Marketing Trends Conference, Paris, France, 23 January 2015; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. The influence of social media marketing activities on customer loyalty: A study of e-commerce industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3882–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrilees, B. Interactive brand experience pathways to customer-brand engagement and value co-creation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, M.; Platania, S.; Santisi, G. Entertainment marketing, experiential consumption and consumer behavior: The determinant of choice of wine in the store. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, M.; Becker, H.; Gravano, L. Hip and trendy: Characterizing emerging trends on Twitter. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardani, W.; Rahyuda, K.; Giantari, I.G.A.K.; Sukaatmadja, I.P.G. Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions in Tourism: A Literature Review. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Int. Manag. 2019, 4, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Ji, H.; Kim, J.; Park, E.; del Pobil, A.P. Deep learning model based on expectation-confirmation theory to predict customer satisfaction in hospitality service. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopalle, P.K.; Lehmann, D.R. Setting quality expectations when entering a market: What should the promise be? Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anabila, P.; Ameyibor, L.E.K.; Allan, M.M.; Alomenu, C. Service Quality and Customer Loyalty in Ghana’s Hotel Industry: The Mediation Effects of Satisfaction and Delight. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 748–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Kamrul Islam Shaon, S.M. A Theoretical Review of CRM Effects on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2015, 4, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Mohamed, S.A.K.; Khalil, A.A.F.; Albakhit, A.I.; Alarjani, A.J.N. Modeling the relationship between perceived service quality, tourist satisfaction, and tourists’ behavioral intentions amid COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of yoga tourists’ perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1003650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralayya, B. Customer Satisfaction at M/s Sindol Bajaj Bidar. Iconic Res. Eng. J. 2021, 4, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Flott, L.W. Customer satisfaction. Met. Finish. 2002, 100, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, I.; Unusan, C.; Cobanoglu, C. Service Quality, Perceived Value and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intention in Restaurants: An Integrated Structural Model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, A.; Abid, G.; Afridi, J.; Elahi, N.; Asif, M. Social media communication and behavioral intention of customers in hospitality industry: The mediating role customer satisfaction. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Joung, H.; Choi, E.; Kim, H. Understanding vegetarian customers: The effects of restaurant attributes on customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2022, 25, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.G. Purchase Intentions and Purchase Behavior. J. Mark. 1979, 43, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions and Their Behavior; Now Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, A.; Dastane, D.O. Factors affecting purchase intention of South East Asian (SEA) young adults towards global smartphone brands. ASEAN Mark. J. 2016, 8, 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Lin, C. Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Yang, S.; Iqbal, Q. Factors affecting purchase intentions in generation Y: An empirical evidence from fast food industry in Malaysia. Adm. Sci. 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, L.C.; Lian, S.B. Customer Engagement in Social Media and Purchase Intentions in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.; Wen, M.; Huang, L.; Wu, K. Online hotel booking: The effects of brand image, price, trust and value on purchase intentions. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2015, 20, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.G.; Minazzi, R. Web reviews influence on expectations and purchasing intentions of hotel potential customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronthal-Sacco, R.; Whelan, T.; Van Holt, T.; Atz, U. Sustainable purchasing patterns and consumer responsiveness to sustainability marketing. J. Sustain. Res. 2019, 2, e200016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Grebinevych, O.; Roubaud, D. Green factors stimulating the purchase intention of innovative luxury organic beauty products: Implications for sustainable development. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, A.; Johnson Jorgensen, J. Influences on Consumer Engagement with Sustainability and the Purchase Intention of Apparel Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Shen, J.; Ashfaq, M.; Shahzad, M. Social media and sustainable purchasing attitude: Role of trust in social media and environmental effectiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhanifard, Y.; Balighi, G.A. Emotional modeling of the green purchase intention improvement using the viral marketing in the social networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming consumers’ intention to purchase green products: Role of social media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuyi, J.; Mamun, A.A.; Naznen, F. Social media marketing activities on brand equity and purchase intention among Chinese smartphone consumers during COVID-19. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Mandal, A.; Kujur, F. The social media marketing strategies and its implementation in promoting handicrafts products: A study with special reference to Eastern India. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2021, 23, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayaa, O.Y.A.; Sulistiyanib, S.; Pudjowatic, J.; Kartikawatid, T.S.; Kurniasih, N.; Purwanto, A. The role of social media marketing, entertainment, customization, trendiness, interaction and word-of-mouth on purchase intention: An empirical study from Indonesian smartphone consumers. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 5, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, U.; Subramanian, N.; Parrott, G. Role of social media in retail network operations and marketing to enhance customer satisfaction. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Ye, Q. First Step in Social Media: Measuring the Influence of Online Management Responses on Customer Satisfaction. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R. Impact of Social Media Marketing, Price Promotion, and Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Satisfaction. Jindal J. Bus. Res. 2017, 6, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Keh, H.T. A re-examination of service standardization versus customization from the consumer’s perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, V.; Peltier, J.W.; Schultz, D.E. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipps, B.; Phillips, B. Social Networks, Interactivity and Satisfaction: Assessing Socio-Technical Behavioral Factors as an Extension to Technology Acceptance. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Asare, C.; Fatawu, A.; Abubakari, A. An analysis of the effects of customer satisfaction and engagement on social media on repurchase intention in the hospitality industry. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Exploring an adverse impact of smartphone overuse on academic performance via health issues: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10, JCMC1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisniyanti, A.; Fah, C.T. The impact of social media marketing on purchase intention of skincare products among indonesian young adults. Eurasian J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction. In The Robustness of Lisrel against Small Sample Sizes in Factor Analysis Models; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K. Structural equation modelling in perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, P.; Nadhila, V.; Sanny, L. Effect of social media marketing on Instagram towards purchase intention: Evidence from Indonesia’s ready-to-drink tea industry. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2020, 4, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashman, R.M.K. Enhancing Customer Satisfaction Through Social Media. Eurasian J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, H.D.; Parahiyanti, C.R. The Effect of Social Media Marketing to Satisfaction and Consumer Response: Examining the Roles of Perceived Value and Brand Equity as Mediation. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2021, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | VIF | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customization | CUST1 | 0.832 *** | 1.763 | 0.766 | 0.865 | 0.682 |

| CUST2 | 0.871 *** | 1.925 | ||||

| CUST3 | 0.772 *** | 1.356 | ||||

| Entertainment | ENTR1 | 0.822 *** | 1.657 | 0.838 | 0.903 | 0.756 |

| ENTR2 | 0.905 *** | 2.550 | ||||

| ENTR3 | 0.879 *** | 2.253 | ||||

| Trendiness | TRND1 | 0.857 *** | 1.746 | 0.814 | 0.890 | 0.729 |

| TRND2 | 0.856 *** | 1.855 | ||||

| TRND3 | 0.848 *** | 1.791 | ||||

| Interaction | INTR1 | 0.830 *** | 1.831 | 0.830 | 0.897 | 0.744 |

| INTR2 | 0.892 *** | 2.004 | ||||

| INTR3 | 0.865 *** | 1.890 | ||||

| Customer satisfaction | CS1 | 0.806 *** | 1.912 | 0.879 | 0.912 | 0.675 |

| CS2 | 0.799 *** | 1.872 | ||||

| CS3 | 0.881 *** | 2.940 | ||||

| CS4 | 0.853 *** | 2.607 | ||||

| CS5 | 0.763 *** | 1.768 | ||||

| Purchase Intention | PI1 | 0.769 *** | 1.763 | 0.758 | 0.803 | 0.576 |

| PI2 | 0.732 *** | 1.925 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.776 *** | 1.356 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Customer satisfaction | 0.822 | |||||

| 2. Customization | 0.607 | 0.826 | ||||

| 3. Entertainment | 0.600 | 0.478 | 0.869 | |||

| 4. Interaction | 0.660 | 0.501 | 0.508 | 0.863 | ||

| 5. Purchase Intention | 0.640 | 0.625 | 0.568 | 0.577 | 0.759 | |

| 6. Trendiness | 0.723 | 0.615 | 0.552 | 0.707 | 0.619 | 0.854 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. customer satisfaction | ||||||

| 2. Customization | 0.738 | |||||

| 3. Entertainment | 0.697 | 0.598 | ||||

| 4. Interaction | 0.763 | 0.624 | 0.603 | |||

| 5. Purchase Intention | 0.855 | 0.885 | 0.776 | 0.776 | ||

| 6. Trendiness | 0.852 | 0.781 | 0.667 | 0.850 | 0.857 |

| Construct | R2 | Q2 Predict |

|---|---|---|

| Customer satisfaction | 0.630 | 0.619 |

| Purchase Intention | 0.551 | 0.526 |

| Hypothesized Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Confidence Intervals Bias Corrected | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||

| Direct Path | |||||

| H1: CUST → PI | 0.288 | 5.643 *** | 0.191 | 0.388 | Accepted |

| H2: ENTR → PI | 0.191 | 3.851 *** | 0.092 | 0.286 | Accepted |

| H3: TRND → PI | 0.105 | 1.731 NS | −0.012 | 0.229 | Rejected |

| H4: INTR → PI | 0.143 | 2.564 ** | 0.035 | 0.252 | Accepted |

| H5: CUST → CS | 0.190 | 5.012 *** | 0.118 | 0.264 | Accepted |

| H6: ENTR → CS | 0.213 | 4.771 *** | 0.121 | 0.299 | Accepted |

| H7: TRND → CS | 0.331 | 6.643 *** | 0.233 | 0.432 | Accepted |

| H8: INTR → CS | 0.223 | 4.162 *** | 0.113 | 0.326 | Accepted |

| H9: CS → PI | 0.179 | 2.820 ** | 0.059 | 0.304 | Accepted |

| Indirect path | |||||

| H10: CUST → CS → PI | 0.034 | 2.447 * | 0.011 | 0.066 | Accepted |

| H11: ENTR → CS → PI | 0.038 | 2.241 * | 0.013 | 0.085 | Accepted |

| H12: TRND → CS → PI | 0.059 | 2.608 ** | 0.020 | 0.110 | Accepted |

| H13: INTR → CS → PI | 0.040 | 2.266 * | 0.011 | 0.079 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anas, A.M.; Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Alrefae, W.M.M.; Daradkeh, F.M.; El-Amin, M.A.-M.M.; Kegour, A.B.A.; Alboray, H.M.M. Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097207

Anas AM, Abdou AH, Hassan TH, Alrefae WMM, Daradkeh FM, El-Amin MA-MM, Kegour ABA, Alboray HMM. Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097207

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnas, Ashraf Mohamed, Ahmed Hassan Abdou, Thowayeb H. Hassan, Wael Mohamed Mahmoud Alrefae, Fathi Mohammed Daradkeh, Maha Abdul-Moniem Mohammed El-Amin, Adam Basheer Adam Kegour, and Hanem Mostafa Mohamed Alboray. 2023. "Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097207

APA StyleAnas, A. M., Abdou, A. H., Hassan, T. H., Alrefae, W. M. M., Daradkeh, F. M., El-Amin, M. A.-M. M., Kegour, A. B. A., & Alboray, H. M. M. (2023). Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context. Sustainability, 15(9), 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097207