Abstract

Recent research confirms that climate change is having serious negative effects on children’s and adolescents’ mental health. Being aware of global warming, its dramatic consequences for individual and collective goals, and the urgent need for action to prevent further warming seems to be so overwhelming for young people that it may lead to paralyzing emotions like (future) anxiety, worries, shame, guilt, and reduced well-being overall. Many children and adolescents feel hopeless in view of the challenges posed by the transformations towards a sustainable future. Feeling powerless widens the gap between knowledge and action which in turn may exacerbate feelings of hopelessness. One of the tasks for parents, educators, and policymakers is therefore to empower young people to act against global warming, both individually and collectively. Psychological resources were identified as precursors of pro-environmental behavior. A theoretical model (and accompanying empirical research) is presented which elaborates on the links between self-efficacy, self-acceptance, mindfulness, capacity for pleasure, construction of meaning, and solidarity on the one hand, and subjective well-being and sustainable behavior on the other hand. This literature review suggests starting points for programs that aim to promote both psychological resources, subjective well-being, and individual and collective pro-environmental behaviors in young people.

1. Introduction

1.1. Youth and Climate Change

Global warming and related changes will affect the younger generation more than anyone else living right now [1]. For example, they will face more extreme weather events like heat waves and floods when compared with older generations [1]. Because of their physical vulnerability, youth will also experience more extreme effects on their health (including birth complications) and deaths due to disasters hitting their physical environment, especially in the global South [2]. This circumstance has fueled worldwide social movements like “Fridays for Future” and has inspired courts to recognize the rights of future generations, e.g., [3]. Today’s young people must come to terms with living a more restricted life and producing a smaller ecological footprint.

Adolescents’ awareness of environmental issues has been on the rise [4], possibly because they have often been confronted with news about the effects of global warming from a very early age—sometimes with the understanding of only the emotional message of “threat” and less about its causes. And oftentimes, it exceeds the awareness of older generations: In a survey of a representative sample of 4103 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states, 51% of the 18-to-34-year-olds but only 29% of the over-55-year-olds believed that global warming will pose a serious threat in their lifetime [5], possibly because it may take 10 to 15 years before global warming will accelerate beyond human control [1]. Data from three nationally representative surveys conducted in the UK in 2020, 2021, and 2022 showed an overall pattern of higher levels of climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions, and emotions among younger generations (born after 1996) when compared to older generations, with the gap being larger and more consistent for climate-related emotions than for climate-related beliefs [6]. More than 50% of a sample of 10,000 young people worldwide reported that they felt each of several negative emotions (i.e., sad, helpless, anxious, afraid, angry, guilty, and powerless) about climate change [7]. Because anxiety is a natural and healthy response to threat, it is not surprising that with increasing awareness young people’s subjective well-being has deteriorated [2].

Evidence has indicated time and again that environmental degradation is associated with anxiety and stress as well as with depressive moods, phobias, sleep disorders, attachment disorders, and substance abuse in young people all over the world (for reviews, see [8,9,10]). “Climate distress” is experienced by growing proportions of children, adolescents, and young adults [11,12]. In sum, perceptions of global warming and its consequences are likely to cause adaptive levels of anxiety stress in many and maladaptive ones (i.e., mental health problems) in a sizeable number of young people [2,13,14,15]. Experiencing floods, droughts and other turbulences connected with global warming may impair their families’ functioning in a way that increases their risk for later mental illness [16]. Promoting young people’s subjective well-being and reducing mental illness by empowering them to collectively mitigate further rises in temperature and to adapt to already occurring consequences through more ecologically sustainable lifestyles seems obvious, especially in light of the fact that “Good Health and Well-being” and “Climate Action” are two of the Sustainable Developmental Goals set by the United Nations for 2030 [17].

1.2. Adopting a Sustainable Lifestyle

An ecologically sustainable lifestyle of society describes a long-term considerate use of the earth’s finite natural resources [18]. For individuals, Hunecke [19] stresses that a sustainable lifestyle not only encompasses ecologically sustainable, i.e., pro-environmental, behavior (PEB). It also includes relatively stable patterns of pro-environmental values, attitudes, and beliefs that are guided by the principles of sustainable development. Many examples demonstrate that individual commitment can provide important impulses that can—when they add up—achieve a long-term impact in the political, social, and cultural transformations ahead [20,21,22]. The Fridays for Future movement is the best example of this ripple effect because it started with a single person and has reached global impact within months, e.g., [23,24]. Single influencers promoting a sustainable lifestyle on social media channels—so-called greenfluencers or eco-influencers—tend to reach millions of young people and can likewise help them adopt or maintain a sustainable lifestyle [25,26]. However, even if young people’s attitudes, beliefs, and values are changing towards sustainable lifestyles, for the planet it ultimately comes down to their PEB.

1.3. Acting Pro-Environmentally

A recent meta-analysis of 41 independent adult research samples showed that many studies have examined the ways in which people translate their concerns into PEB [27]. The most commonly used theoretical frameworks to predict and explain PEB are the Theory of Planned Behavior [28], the Norm Activation Theory [29], and the Value-belief-norm Theory [30] which include values, norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control as predictors for PEB and intentions to perform PEB. In a meta-analysis across 56 adult datasets, the Comprehensive Action Determination Model of the determinants of individual environmentally relevant behavior was developed, which combined these most common theories of environmental psychology. It showed that intentions for PEB, together with perceptions of behavioral control, accounted for up to 55% of the variance in self-reported PEB [31]. Thiermann and Sheate’s [32] two-pathway model of PEB elaborates upon the Comprehensive Action Determination Model, which does not include psychological resources. Thiermann and Sheate [32] emphasize relational variables: Connectedness with nature tends to increase self-transcendence values and to decrease self-enhancement values. Connectedness with nature was shown to influence individuals’ personal norms, which in turn predicted their pro-environmental intentions. In their model, empathy (with nature) is predicted by connectedness with nature, by the awareness of the consequences (original model), and by the social context (new variable). Empathy is linked with negative and positive emotions and is expected to be a strong predictor of compassion. In Thiermann and Sheate’s [32] theoretical model, compassion influences pro-environmental behavioral intentions directly and indirectly via personal norms. The authors hypothesize that with increased activation of relational pathways, the motivation to act pro-environmentally becomes more intrinsic because the normative pathways are supplemented by an emotional base.

Only very few studies have studied children’s and adolescents’ pro-environmental intentions or behaviors with reference to aspects of the above-mentioned theoretical models, e.g., [33,34]. For example, de Leeuw et al. [33] establish that attitudes towards PEB, injunctive norms regarding PEB, descriptive norms for PEB, and perceived control over PEB accounted for 68% of the variance in high school students’ behavioral intentions and 27% of the variance in their self-reported PEB. In this sample of youth, the proportion of explained variance was strikingly lower than in adult samples [31]. Although children’s and adolescents’ possibilities to show PEB are more limited than adults’ (e.g., because of limited financial resources or freedom of choice), it is still useful to investigate these predictors because their influence on their PEB through educational measures tended to be high [35,36]. However, education for sustainable development which is restricted to the transfer of knowledge may not be sufficient. This was the result of a study in which knowledge of the causes and effects of climate change was not a direct predictor of PEB among youth, whereas social norms and self-efficacy were strong predictors [37]. Similarly, in the study by Tamar et al. [38] with N = 284, Indonesian college students’ environmental knowledge was not a significant predictor of their general PEB and in the study by Razali et al. [39], the effect of pro-environmental attitudes and self-efficacy on the self-reported PEB of N = 500 14- to 18-year-olds in Indonesia was stronger than the effect of environmental knowledge.

1.4. Psychological Barriers to a Sustainable Lifestyle in Young People

Gaps exist between youths’ concerns, beliefs, awareness, and norms on the one hand and their pro-environmental intentions on the other hand [40], much like in adults [41]. This means that although people have the attitudes, beliefs, and values that correspond to a sustainable lifestyle, they do not (always) act accordingly. For example: The intention to make pro-environmental consumption decisions and the willingness to forego amenities for the environment was low in a sample of more than 4000 respondents between 15 and 29 years from 19 European countries, although the threat of environmental degradation was perceived to be high [42]. Correlations between pro-environmental intentions and self-reported PEB ranged between medium sized (r = 0.38) and high (r = 0.59) in samples of 12- to 16-year-olds [33] and 12- to 17-year-olds [43], respectively. These results suggest that additional factors need to be taken into account when predicting PEB, especially when considering that self-reported PEB could be biased by shared method variance or social desirability [44].

Feeling overwhelmed and paralyzed by the severity of the global environmental problems and the magnitude of the necessary transformations are two reasons that may explain the gaps between young peoples’ awareness, their intentions, and their behavior. For example, 12% of a representative sample of 14- to 22-year-olds in Germany stated that they did not want to join Fridays for Future, because they felt that “they could not change anything anyway” [45]. Indeed, perceived self-efficacy is included in the Theory of Planned Behavior-based models as the locus of control, e.g., [33]. In general, “motivational outcomes of self-efficacy are choice of activities, effort, persistence, and achievement” [46] (p. 4). It is considered to be an important psychological factor that is also responsible for a person’s pro-environmental intentions and actual PEB [47]. In Kollmuss and Agyeman’s [41] model, a lack of self-efficacy is one of the emotional blocks that acts as a barrier to PEB. Several interview studies concur that individual and collective self-efficacy seems to be low in many young people, e.g., [48,49,50]. Lack of self-efficacy seems to affect not only individual PEB but also political activism. This is unfortunate because it is precisely the involvement in protest movements that can empower young people and enhance their personal growth [24,51]. Feelings of frustration and powerlessness because of sluggish government activity tend to exacerbate young people’s climate distress. This can lead to further impairments in subjective well-being [7], also among the activists [52]. However, a higher locus of control or self-efficacy can lead to a greater willingness to act. Depending on the perceived opportunities and control over the implementation of the measures, the willingness to act pro-environmentally was generally positively related to the perceived usefulness of pro-environmental actions among Chinese youth [53].

1.5. Further Psychological Resources, a Sustainable Lifestyle with PEB, and Subjective Well-Being

There are additional personal psychological resources besides high self-efficacy that contribute to the promotion of a sustainable lifestyle. Based on the foundations of positive psychology, Hunecke [19] developed a theoretical model on the presumed connections between six psychological resources and a sustainable lifestyle. Noteworthy is Hunecke’s [19] idea of regeneration, i.e., that the future state (after a successful transformation) needs to be a psychologically desirable state that people strive to achieve. Hunecke [19] places less emphasis on the actual state or on a dystopian future to be avoided. Psychological resources are supposed to influence not only a sustainable lifestyle but also subjective well-being in a positive way. Thus, Hunecke’s [19] model could provide valuable starting points for developing interventions and educational programs to promote both subjective well-being and a sustainable lifestyle in youth.

Unfortunately, it is one of the caveats of positive psychology and sustainability research that valuable theoretical work is seldom accompanied by empirical proof of its assumptions. Although children and adolescents will be affected the most by the consequences of global warming [54], research on the association between their subjective well-being, psychological resources, and sustainable lifestyle is sparse. The aim of this review is therefore to synthesize the literature on how subjective well-being and a sustainable lifestyle are linked with the personal psychological resources of young people, both theoretically and empirically, and to sketch some interventions that promote both subjective well-being and pro-environmental values, intentions, and behavior. Although the theoretical model described below was developed for adults, and although it is obvious that children and adolescents have fewer (and perhaps different) opportunities to act pro-environmentally, the general associations between psychological resources, subjective well-being, and sustainable lifestyles are believed to be the same.

2. A Model of Psychological Resources and a Sustainable Lifestyle

In Hobfoll’s [55,56] Conservation of Resources theory “resources are those entities that either are centrally valued in their own right […] or act as a means to obtain centrally valued ends […]” [55] (p. 307). Personal characteristics, such as high self-esteem, are one of the four basic categories of resources people value and try to obtain in order to avoid the experience of stress [55,56]. Environmental psychology has elaborated on concepts from Positive Psychology and has identified psychological resources and positive emotions as important precursors of individual PEB [57]. Wamsler and Restoy [58] argue that “sustainability is fundamentally about our relationships, i.e., the relationship to oneself, what we believe and value, and how we view ourselves in relation to the world around us” (p. 3). These authors emphasize that emotional intelligence is key to the transformation to sustainability and that sustainable behavior goes beyond the individual. Ronen and Kerret [59] propose a common holistic definition of well-being, i.e., sustainable well-being, which encompasses the key components of both Positive Psychology and sustainability and recognizes the links between the well-being of individuals and the well-being of systems like the natural environment. Building on these connections, Hunecke [19,60] has developed the Pleasure-Goal Regulation-Meaning Theory of Well-being, which will be presented in the following.

Pleasure-Goal Regulation-Meaning Theory of Well-Being by Hunecke [19]

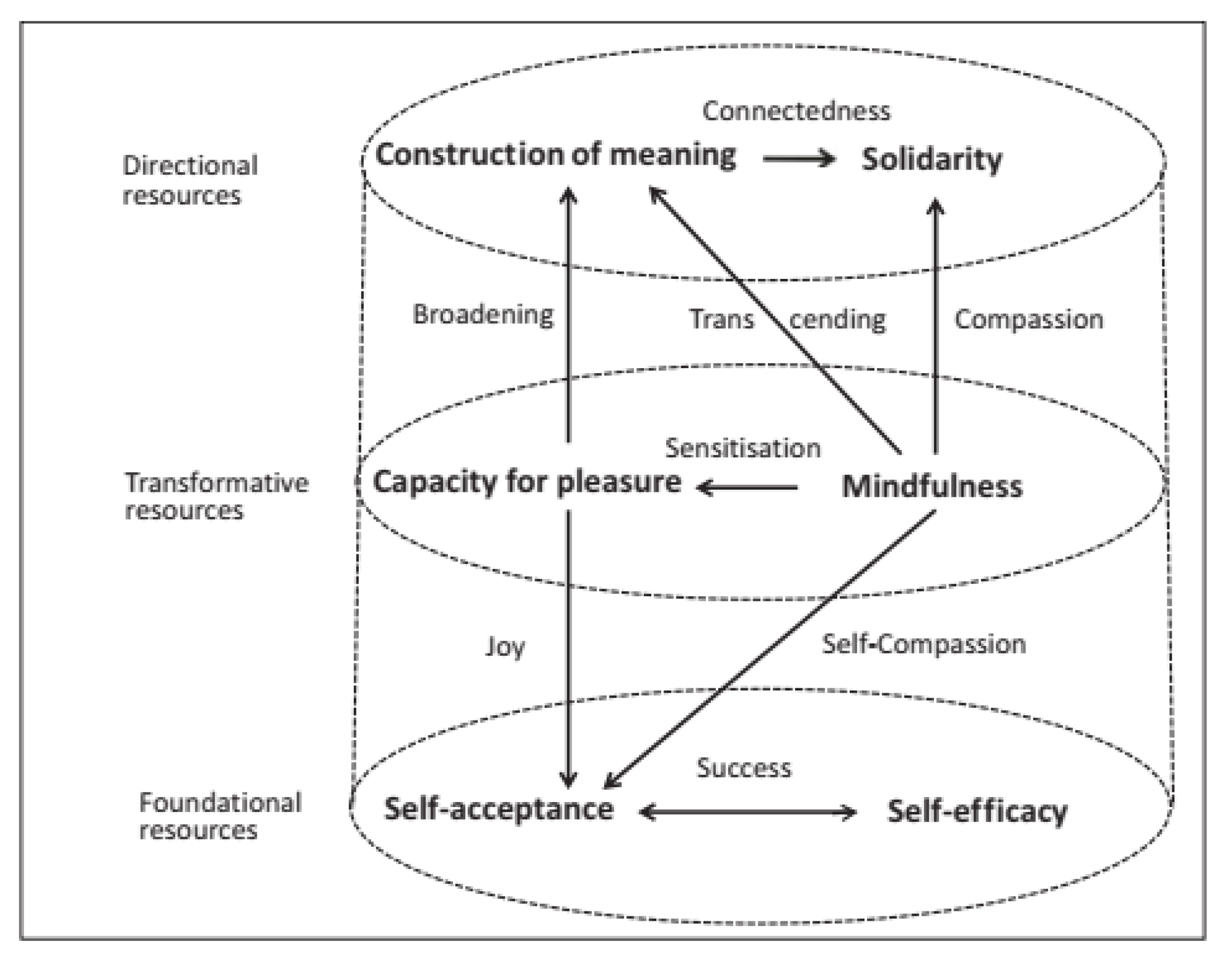

Hunecke [19] argues that beyond technological innovations and an increase in organizational efficiency, cultural transformation is indispensable for the transition towards a sustainable lifestyle. Drawing on social–ecological research, environmental psychology, and Positive Psychology, he states that people need to evaluate their future life in a more sustainable society as enjoyable before they manage to change their behavior and maintain these changes over long periods of time. According to Hunecke’s [19] theory, well-being can be achieved by three orientations to happiness: hedonism, goal regulation, and meaning. A fulfilled life is based on these three pillars and their associated emotions, such as sensual pleasure, satisfaction, and pride, as well as security, connectedness, and trust. Hunecke [19] identified six psychological resources that support individuals in realizing these strategies for leading a happy life while enhancing both subjective well-being and sustainable behavior. They are divided into foundational resources (self-acceptance, self-efficacy), transformational resources (capacity for pleasure, mindfulness), and directional resources (construction of meaning, solidarity). Their multiple interrelations are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Interrelations between six psychological resources for a sustainable lifestyle from Hunecke [12,48]. Note: From “Psychology of sustainability. From sustainability marketing to social-ecological transformation”, by M. Hunecke, 2022, Springer, (p. 94). Copyright 2022 by the Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG. Reprinted with permission.

According to Hunecke’s [19] theory, the personality-strengthening foundational resources of self-acceptance and self-efficacy do not automatically promote sustainable behavior because they are primarily concerned with achieving individual goals and needs, which can be very materialistic and thus ecologically unsustainable. The capacity for pleasure and mindfulness have a transformative function and “exhibit the greatest potential when it comes to questioning and changing the current lifestyle in a reflexive manner, independently of critical life events and developmental tasks” [60] (p. 41). Directional resources are key when it comes to translating intentions for sustainable behavior into action. Both the construction of meaning and solidarity within a group can stimulate reflective thinking, which probes old values and attitudes. New values emerge within the group and are maintained by consensus. Hunecke [19] stresses that these psychological resources are mutually reinforcing and that the omission of one resource may be compensated by another one.

3. Empirical Associations between the Psychological Resources and PEB

Unfortunately, the associations between psychological resources and a sustainable lifestyle which Hunecke [19] proposed lack empirical support, especially for children and adolescents, because most studies have focused on the negative effects of climate change on people’s well-being and the normative, social, and emotional barriers to a sustainable lifestyle. Apart from self-efficacy, few studies exist for adults (and even fewer for youth) that examine the relations between psychological resources and sustainable attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors. Nonetheless, some studies indicate at least indirect links or have examined related constructs in youth. The following sections present research findings that support the above-mentioned model, beginning with the relationship between subjective well-being and sustainable lifestyles. They are followed by each psychological resource included in Hunecke’s [19] model that is related to pro-environmental values, beliefs, intentions, or behaviors with special emphasis on children and adolescents wherever possible.

3.1. Well-Being and PEB

According to Hunecke’s [19] Pleasure-Goal Regulation-Meaning model, subjective well-being and accompanying positive emotions are the basis for a sustainable lifestyle and therefore for PEB. In a recent meta-analysis of 78 studies, a moderate correlation of r = 0.24 between subjective well-being and overall PEB was reported for adults [61]. Another meta-analysis concluded that nature connectedness was significantly associated with vitality (r = 0.24), positive affect (r = 0.22), and life satisfaction (r = 0.17) [62]. The few (quasi-) experimental studies included in the meta-analysis by Zawadzki et al. [61] suggested “that there is potential for creating a positive self-reinforcing cycle between pro-environmental engagement and subjective well-being, which may promote long-term environmental behaviors and enhanced subjective well-being” [61] (p. 11). Already experiencing oneself as pro-environmental, i.e., having a green self-image, was already associated with more life satisfaction in a large study with participants from 35 countries, 17 of which were not from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic; [63]) nations [64]. For children, positive relations between well-being, life satisfaction or positive emotions, and a sustainable lifestyle (including pro-environmental values and actions) were supported in samples from around the world. For example, a correlation of r = 0.26 between PEB and well-being (here: ratio of positive and negative emotions) was corroborated in a study with over 1900 fifth and sixth graders from Israel [65]. Life satisfaction was positively associated with connectedness to nature, beliefs in environmental behavior, and self-reported PEB (r = 0.59, r = 0.45, and r = 0.20, respectively) in a study with N = 120 10- to 19-year-olds from Spain [66]. Happiness was associated with connectedness to nature (r = 0.31) and self-reported PEB (r = 0.19) in a study with N = 296 9- to 12-year-olds from Mexico [67]. In a Swedish study, adolescents with higher life satisfaction showed more meaning-focused coping with climate change which was associated with PEB [68,69]. And in Italy, pro-environmental behavior was associated with personal and social well-being (both r = 0.21) in a sample of N = 1925 adolescents aged 14 to 20 years [70].

3.2. Construction of Meaning and PEB

Meaning-focused coping involves reflecting upon the meaning and benefits of a difficult situation. Because it tends to engender positive emotions like trust and hope [71], it can be considered a psychological resource. The just-mentioned empirical results from the studies by Ojala [68,69] support Hunecke [19] in modeling the construction of meaning to be one of the directional psychological resources that may foster both subjective well-being and actions toward a sustainable lifestyle.

More research supports the notion that engaging in meaningful activities is one of the mechanisms that may explain the link between subjective well-being and a sustainable lifestyle. Using an implicit association test, Venhoeven and colleagues [72] found that environmentally friendly actions were implicitly associated with positive emotions. After analyzing self-report questionnaires, they concluded that this relationship “is not merely a matter of social desirability, but rather a matter of meaning: acting sustainably is perceived as a moral choice and thus as a meaningful course of action, which can elicit positive emotions” [72] (p. 8). Klement and Terlau [73] concluded that college students who were involved in (extra)curricular activities in favor of sustainable development tended to report higher eudaimonic well-being related to self-discovery and meaning in life than a control group. Another study underlined the prominent role of environmental hope in promoting both PEB and the well-being of high school students. It highlighted the potential of hope-based programs to achieve both outcomes among adolescents [65]. Chawla [74] concluded in her literature review that constructive hope was an important resource for children and youth when it comes to coping with an increasingly degraded natural environment. In her review, she also presented empirical evidence to the effect that social trust [75] and social support [76] can give meaning to actions and thereby encourage children and adolescents. This leads to the psychological resource of solidarity.

3.3. Solidarity, Empathy, Compassion, and PEB

According to Hunecke [19], solidarity encompasses both personal responsibility for the welfare of other people and collective self-efficacy. Hill and Howell [77] established a link between prosocial spending and happiness, especially for adults with higher levels of self-transcending values, i.e., concern for other people. In another meta-analysis, Curry et al. [78] found acts of kindness and helpfulness to be related to well-being. Studies conducted within the framework of positive youth development (such as the model from the Australian Temperament Project; [79]) and models of global competencies confirmed Hunecke’s [19] assumption that solidarity is also one of the directional psychological resources that may lead to more subjective well-being for adolescents. They established that solidarity in a broad sense was related to adolescents’ positive development and emotional health [80]. That solidarity is important for the transformation toward a sustainable lifestyle in children and adolescents is confirmed by the results of Fielding and Head [43], who studied two samples of 12- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 24-year-olds. These authors concluded that attributing greater responsibility for the protection of the environment to the community was related to stronger pro-environmental intentions and actions. In contrast, attributing greater responsibility to the government for environmental protection was related to more negative environmental intentions and behavior on the part of the participants. Additionally, Jugert et al. [81] established experimentally that collective efficacy bolstered young adults’ pro-environmental intentions by increasing their self-efficacy. Joshi and Rahman [82] discovered that perceived consumer effectiveness was one of the key psychological determinants of young consumers’ sustainable purchase decisions. In a recent survey on the Fridays for Future movement, young people in Germany reported that friends participating in the movement and identification with others engaging in climate protection were the strongest psychological drivers for their pro-environmental activism [83].

Solidarity in the sense of caring for other people, however, requires a certain amount of empathy and compassion [84]. Links between empathy and pro-environmental intentions, environmental values, and attitudes in children have been corroborated by several studies. In an experimental study, young children took either the perspective of a perpetrator or a victim of environmental harm. Results indicated that children in the victim perspective showed more empathy with the environment because they rated the harmful behavior to be more reprehensible than children in the perpetrator perspective [85]. Similar moral judgments were obtained in an intervention study with preschoolers who took the perspective of animals who were living in a forest [86]. Pearce et al. [87] specified that identifying with animals (as compared to landscapes) increased preadolescents’ empathy and resulted in stronger anticipatory guilt over environmental degradation, which in turn stimulated their intentions towards pro-environmental behaviors. Empathic concern (for other people) among adolescents did not have a direct effect on intentions or self-reported PEB, but influenced PEB indirectly via its effects on behavioral, normative, and control beliefs [33]. Empathy towards animals furthermore mediated the positive relation between childhood attachment to a pet and the avoidance of eating meat as adults [88]. Intervention studies have demonstrated that children’s empathy and prosocial behavior could be increased through mindfulness interventions in schools [89,90,91], which leads to the transformative psychological resource of mindfulness.

3.4. Mindfulness and PEB

In recent years mindfulness has gained much attention in (environmental) psychology because connectedness with the natural world is one of the tenets of mindfulness and compassion [92]. Ericson et al. [93] present four main reasons for the well-established positive impact of mindfulness practice on physical and mental well-being: (1) to be engaged in the present moment (and not in the past or the future) is positively correlated with happiness; (2) mindfulness increases empathy and compassion, which in turn tend to enhance social relationships; (3) mindfulness stimulates people to recognize their own values (instead of those promoted by society or commercials) and helps them to behave in accordance with them; and (4) with its stress on post-materialistic values, mindfulness can help in reducing the power of materialistic welfare on well-being. In Ericson’s model, mindfulness also contributes directly to sustainable behavior because the chances to achieve personal well-being take center stage in peoples’ awareness. When empathy and compassion increase through the practice of mindfulness, they support people in connecting with humans (and animals) in other parts of the world who are affected by unsustainable decisions, and with their natural environment and its degradation. Empirical relations between mindfulness and subjective well-being have been confirmed in meta-analyses for youth, e.g., [94]. For adults, there is evidence of an indirect connection with PEB by way of a decrease in materialistic values and an increase in subjective well-being [95,96]. In a systematic review, Fischer et al. [97] found some empirical support for their theoretical propositions that mindfulness contributes (1) to the disruption of mental and behavioral routines, (2) to a narrowing of the attitude-behavior gap, (3) to an increase in non-materialistic values, (4) to an enhancement of well-being, and (5) to an increase in prosocial behavior. Because of these ideas, mindfulness was included in intervention programs that aimed at promoting PEB, e.g., [98]. A mindfulness-based intervention in schools showed a strong effect on precursors of sustainable consumption behavior in 15-year-olds [99]. After another four-month school-based training program with 10- to 12-year-olds, the intervention group showed a significant increase in pro-environmental beliefs, whereas the control group did not [100]. Even a short-term mindful activities intervention in a nature reserve with nine- and ten-year-olds resulted in an increase in their nature connectedness and their positive affect [101]. In an interview study, adult practitioners reported that they were able to enjoy their lives more fully since practicing mindfulness. They also appreciated the natural environment more intensely at the sensory level, which reinforced their emotional connectedness to nature at the level of experience [102]. Raising the awareness of sensory experiences or increasing the capacity for pleasure could be another mechanism by which mindfulness impacts the transition toward a sustainable lifestyle, e.g., [103].

3.5. Capacity for Pleasure and PEB

Hunecke [19] explains the capacity for pleasure as enjoying sensory experiences. In the literature, physical pleasure is considered to be part of hedonic well-being and may refer, for example, to the pleasure of eating a nice dinner, e.g., [104]. Bryant and Veroff [105] defined savoring as “the capacity to attend to, appreciate, and enhance the positive experiences in one’s life” (p. 2) and linked it directly to people’s well-being. In their diary studies with undergraduates, Oishi et al. [106] confirmed that the experience of physical pleasure was strongly associated with subjective well-being. Beyond the already reported links between subjective well-being and a sustainable lifestyle, the capacity for pleasure was specifically linked to a sustainable lifestyle: Nurse et al. [107] established that young adults’ motivation for sensory pleasure was positively associated with their nature-related behavior, such as hiking and visiting national parks, national forests, or wilderness areas. Apathy or lack of environmental concern toward environmental issues as well as anthropocentrism was negatively associated with the self-reported level of motivation for sensory pleasure [107]. Similarly, in a study with 8- to 12-year-olds, girls reported to be more strongly connected to nature than boys. This seemed to be a function of their more intensive sensory engagement with nature in visual, auditory, and tactile terms [108]. In another study, young adults’ pro-environmental purchasing was predicted by their intrinsic motivation to perform pro-environmental actions, i.e., because they enjoyed doing so [109]. Finnish college students’ enjoyment of the natural environment furthermore predicted their PEB via their intentions [110]. Unfortunately, most of these studies do not provide any insights into the direction of effects because they are correlational. However, since the capacity for pleasure is closely related to, if not part of, subjective well-being [111], it is likely that a sustainable lifestyle and the capacity for pleasure are mutually reinforcing (as noted earlier in this article).

3.6. Self-Acceptance and PEB

Self-acceptance is often seen as another dimension of well-being, e.g., [112], which is strongly linked to positive emotions as well [113,114]. In Hunecke’s [19] model, accepting oneself is one of the foundational resources that at first sight may seem counterintuitive to promote a sustainable lifestyle because this is primarily concerned with achieving individual goals and needs. But self-acceptance can also be viewed as a resource in personality development, which can help in overcoming self-enhancement values (for example through consumption) and in developing self-transcendent values. Little research has been conducted on the predictive power of self-acceptance on a sustainable lifestyle. A closely related meta-analysis noted a significant positive association between self-acceptance and nature connectedness (r = 0.17) in four samples with N = 686 adults [115]. Participants in a nature-based intervention study reported that experiences of self-acceptance raised their expectations that they would be able to come to terms with future challenges [116]. In keeping with this, another intervention study demonstrated that adolescents’ expeditions into the wilderness increased both their self-esteem (a construct which also includes aspects of self-acceptance; r > 0.50; e.g., [117]) and their nature connectedness [118]. The positive association between students’ eco-anxiety and their intention to act pro-environmentally was moderated by the discrepancy between their self-perception and their desire to see themselves [119]. Indirect effects were underlined in a study by Queiroz et al. [120]. Self-esteem and environmental values were both higher in adolescents from homes that were characterized by parental warmth. Higher levels of self-esteem seem to be associated with giving environmental values greater priority. In an earlier study, a two-week environmental education camp boosted children’s self-esteem, increased their curiosity about nature, and fostered their outdoor skills [121]. In summary, the research findings support the assumption that self-acceptance functions as a foundation or part of subjective well-being that helps young people develop and maintain a sustainable lifestyle.

3.7. Self-Efficacy and PEB

The other foundational psychological resource at the basic level of Hunecke’s [19] model is self-efficacy. It is known to be a strong contributor to subjective well-being and positive emotions in adolescents [122]. As mentioned earlier, self-efficacy is a psychological resource that is frequently under study when examining individual preconditions for a sustainable lifestyle and for PEB. In Klöckner’s [31] meta-analytic model, behavioral control—a construct closely related to self-efficacy—was a direct predictor of PEB. In a more recent meta-analysis, self-efficacy was the factor that was most closely related to behavior adapting to climate change [123]. Studies with adolescents indicated that self-efficacy contributed to forecasting their general ecological intentions which in turn predicted their general ecological behavior [124] and their self-reported PEB [33,37,43]. In addition, greater self-efficacy was associated with high school students’ increased participation in climate activism [125]. Hunecke [19] assumes that both self-efficacy and self-acceptance function as resources to become more independent from social comparisons which in turn increases personal sustainability.

4. Implications for Practice

The results reported so far suggest that promoting subjective well-being by strengthening psychological resources can help children and adolescents adopt sustainable lifestyles, when combined with providing them with knowledge about current and impending climate changes and when teaching appropriate coping strategies. Strengthening psychological resources may indeed be the factor that enhances the success of environmental education. A recent meta-analysis over N = 169 studies with 519 effect sizes established the effectiveness of environmental education for children’s and adolescents’ environmental knowledge (g = 0.953), attitudes (g = 0.384), intentions (g = 0.256), and PEB (g = 0.410) [36]. None of the examined moderators of program effectiveness (i.e., characteristics of the study, the design, the intervention, the participants, and the outcomes) were significant. It thus remained unclear which characteristics of the educational programs were responsible for their success in the various domains. Psychological resources may be the missing link that accounts for the influence between environmental education and a sustainable lifestyle in youth.

This idea suggests new approaches to education for sustainable development at different stages of young people’s lives. Education could focus, for example, on strengthening psychological resources rather than just addressing the negative impact of the climate crisis on subjective well-being as a motivation for PEB. Ronen and Kerret [59] proposed a holistic definition of well-being, i.e., sustainable well-being, which encompasses key components of both positive psychology and sustainability and recognizes the links between the well-being of individuals and the well-being of the natural environment. By integrating the benefits of positive education and environmental education into a coherent approach, Ronen and Kerret [59] provided a roadmap to guide schools (and other educational institutions) in their approach to environmental education with the aim of enhancing sustainable well-being. Three of their 10 “thinking rules” were (1) think and feel positive, (2) identify and use individual strengths, and (3) together and integrative. With these rules in mind, caregivers and teachers could teach children from an early age onward to be aware of their personal psychological resources and to strengthen them. Learning to enjoy food through sufficient time for meals and teachers as role models [126] and regular walks in forests and parks with a mindful sensory experience of flora and fauna [127], for example, can be organized in nearly every preschool, kindergarten, or school alongside explaining the basics of ecologically sustainable behavior [128,129]. Forest schools provide an opportunity to teach primary and secondary school students not only about the climate crisis and ecologically sustainable behavior but also to instill solidarity and social responsibility in them [130]. When in nature, new emphasis could be placed on experiencing pleasure, including the pleasure of learning [131]. Sobel [132] provided a comprehensive overview of outdoor (pre)school approaches around the world that have been developed to foster children’s connection to nature. When empirical results were available, they consistently emphasized the positive effects on children’s well-being and behavior. Thus, approaches to promoting sustainable lifestyles through education for sustainable development already exist in many countries and are well suited to be expanded by another focus—that of promoting psychological resources which are part of the “inner nature” of human development.

5. Implications for Research

In research, there is an urgent need for quasi-experimental interventions to establish the causal links between strengthening children’s and adolescents’ personal resources while at the same time preparing them for a sustainable lifestyle, organizing collective action in support of the transformation, and adapting to the unavoidable changes in the environment. Unfortunately, many of the studies cited above used correlational (rather than causal) designs. Most results stemmed from cross-sectional studies which relied almost exclusively on participants’ self-reports of their PEB with their well-known flaws. Most importantly, none of the studies have collected data on the link between psychological resources and subjective well-being with a sustainable lifestyle. Only a handful of interventions on the promotion of a sustainable lifestyle among youth meet the high methodological standards for meaningful evaluations, by having, for example, a randomized controlled design. Future studies on the relation between psychological resources and PEB should close this gap by meeting higher methodological standards in longitudinal, randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental intervention studies.

6. Conclusions

Today’s youth will bear the brunt of the unpleasant changes of the rapid increase in global temperatures (climate adaptation) while their PEB may have little effect on local warming [1]. It is therefore necessary to support the younger generation in developing and strengthening their (psychological) resources for the cultural, social, and political transformations that are needed to mitigate climate change and to alleviate the worst consequences—by individual sustainable lifestyles and by collective climate activism. Hunecke’s [19] Pleasure-Goal Regulation-Meaning Theory of Well-being provides the theoretical framework for this review of empirical research on the associations between six psychological resources and PEB in children and youth. Empirical research on the promotion of psychological resources to increase both well-being and a sustainable lifestyle in young people was found to be scarce. However, for each of the six psychological resource construction of meaning, solidarity, mindfulness, capacity for pleasure, self-efficacy, and self-acceptance, at least indirect associations with PEB and well-being were established, which advocates for the fostering of children’s and adolescents’ psychological resources in order to promote their PEB is backed by empirical support. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials that allow conclusions to be drawn about causal relations between the constructs under scrutiny. Nevertheless, the existing literature indicates that empowering youth will not only help them to downregulate their eco-anxiety and increase their well-being and agency but will also narrow the gap between their environmental concerns, attitudes, and intentions and their actual PEB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V. and M.v.S.; literature review, K.V.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V.; writing—review and editing, K.V. and M.v.S.; supervision, M.v.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thiery, W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J.; Palmer, A.; Markey-Towler, R. Review of Literature on Impacts of Climate Litigation; Melbourne. 2022. Available online: https://www.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/4238450/Impact-lit-review-report_CIFF_Final_27052022.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- List, M.K.; Schmidt, F.T.C.; Mundt, D.; Föste-Eggers, D. Still green at fifteen? Investigating environmental awareness of the PISA 2015 population: Cross-national differences and correlates. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, J.R. Global Warming Age Gap: Younger Americans Most Worried. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/234314/global-warming-age-gap-younger-americans-worried.aspx (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Poortinga, W.; Demski, C.; Steentjes, K. Generational differences in climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions and emotions in the UK. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.E.L.; Sanson, A.V.; van Hoorn, J. The psychological effects of climate change on children. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Reilly, K.; Everitt, H.; Gilliland, J.A. Review: The impact of climate change awareness on children’s mental well-being and negative emotions—A scoping review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strife, S.J. Children’s environmental concerns: Expressing ecophobia. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanson, A.V.; van Hoorn, J.; Burke, S.E.L. Responding to the impacts of the climate crisis on children and youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciberras, E.; Fernando, J.W. Climate change-related worry among Australian adolescents: An eight-year longitudinal study. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Assembly of the United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Steffen, W.; Rockström, J.; Richardson, K.; Lenton, T.M.; Folke, C.; Liverman, D.; Summerhayes, C.P.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cornell, S.E.; Crucifix, M.; et al. Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8252–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunecke, M. (Ed.) Psychology of Sustainability: From Sustainability Marketing to Social-Ecological Transformation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-16751-5. [Google Scholar]

- Farache, F.; Grigore, G.; McQueen, D.; Stancu, A. The role of the individual in promoting social change. In Responsible People; Farache, F., Grigore, G., Stancu, A., McQueen, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-3-030-10739-0. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K. Political agency: The key to tackling climate change. Science 2015, 350, 1170–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. Is the 1.5 °C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sabherwal, A.; Ballew, M.T.; Linden, S.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H.; Maibach, E.W.; Kotcher, J.E.; Swim, J.K.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Leiserowitz, A. The Greta Thunberg Effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Bellemo, M. Children and youth in the climate crisis. BJPsych Bull. 2021, 45, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdecker, B. Travel-related influencer content on Instagram: How social media fuels wanderlust and how to mitigate the effect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Meijers, M.H.C.; Zwart, W. The importance of influencer-message congruence when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Li, L.M.W. The relationship of environmental concern with public and private pro-environmental behaviours: A pre-registered meta-analysis. Euro J. Soc. Psych 2023, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Howard, J. A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior; Rushton, J.P., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; Lawerence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 89–211. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiermann, U.B.; Sheate, W.R. Motivating individuals for social transition: The 2-pathway model and experiential strategies for pro-environmental behaviour. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 174, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L.; Cheung, C.T.Y. Why do young people do things for the environment? The effect of perceived values on pro-environmental behaviour. YC 2022, 23, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, J.; Leijten, P.; Spitzer, J.; Thomaes, S. Does environmental education benefit environmental outcomes in children and adolescents? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, K.C.; Ardoin, N.M.; Gruehn, D.; Stevenson, K. Exploring a theoretical model of climate change action for youth. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 2389–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamar, M.; Wirawan, H.; Arfah, T.; Putri, R.P.S. Predicting pro-environmental behaviours: The role of environmental values, attitudes and knowledge. MEQ 2021, 32, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, G.; Fatmawati, S.; Hidayat, R.; Farooq Mujahid, M.U. Psychological factors influencing pro-environmental behavior in urban areas. WSIS 2023, 1, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Gjersoe, N.; O’Neill, S.; Barnett, J. Youth perceptions of climate change: A narrative synthesis. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanpää, L. Youth environmental consciousness in Europe: The influence of psychosocial factors on pro-environmental behaviour. In Green European: Environmental Behaviour and Attitudes in Europe in a Historical and Cross-Cultural Comparative Perspective; Telešienė, A., Gross, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 202–220. ISBN 9781317301189. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, K.; Pankowska, P.K.; Brick, C. Identifying bias in self-reported pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Nukleare Sicherheit. Zukunft? Jugend Fragen! Umwelt, Klima, Politik, Engagement—Was Junge Menschen Bewegt. Available online: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/zukunft_jugend_fragen_studie_bf.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Chapter Four—Self-efficacy and human motivation. In Advances in Motivation Science; Elliot, A.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, A.; Roberts, O.; Chiari, S.; Völler, S.; Mayrhuber, E.S.; Mandl, S.; Monson, K. How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.A.; Davison, A. Disempowering emotions: The role of educational experiences in social responses to climate change. Geoforum 2021, 118, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielking, M.; Moore, S. Young people and the environment: Predicting ecological behaviour. Aust. J. Env. Educ. 2001, 17, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budziszewska, M.; Głód, Z. “These are the very small things that lead us to that goal”: Youth climate strike organizers talk about activism empowering and taxing experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, B. On Mourning Climate Change. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/reality-play/201812/mourning-climate-change (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Dong, X.; Geng, L.; Rodríguez Casallas, J.D. How is cognitive reappraisal related to adolescents’ willingness to act on mitigating climate change? The mediating role of climate change risk perception and believed usefulness of actions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Burke, S.E.L. Climate change and children: An issue of intergenerational justice. In Children and Peace; Balvin, N., Christie, D.J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 343–362. ISBN 978-3-030-22175-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Culture, and Community: The Psychology and Philosophy of Stress; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-306-48444-5. [Google Scholar]

- Corral Verdugo, V. The positive psychology of sustainability. Env. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Restoy, F. Emotional intelligence and the sustainable development goals: Supporting peaceful, just, and inclusive societies. In Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-3-319-71066-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen, T.; Kerret, D. Promoting sustainable wellbeing: Integrating positive psychology and environmental sustainability in education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunecke, M. Psychology of sustainability. In Personal Sustainability; Parodi, O., Tamm, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 33–50. ISBN 9781315159997. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzki, S.J.; Steg, L.; Bouman, T. Meta-analytic evidence for a robust and positive association between individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors and their subjective wellbeing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83; discussion 83–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. How green self image is related to subjective well-being: Pro-environmental values as a social norm. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 149, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerret, D.; Orkibi, H.; Bukchin, S.; Ronen, T. Two for one: Achieving both pro-environmental behavior and subjective well-being by implementing environmental-hope-enhancing programs in schools. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Pinto, N.; Garrido, D.; Gértrudix-Barrio, F.; Fernández-Cézar, R. Is knowledge of circular economy, pro-environmental behavior, satisfaction with life, and beliefs a predictor of connectedness to nature in rural children and adolescents? A pilot study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Hernández, L.F.; Sotelo-Castillo, M.A.; Echeverría-Castro, S.B.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.O. Connectedness to nature: Its impact on sustainable behaviors and happiness in children. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojala, M. Coping with climate change among adolescents: Implications for subjective well-being and environmental engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Young people and global climate change: Emotions, coping, and engagement in everyday life. In Geographies of Global Issues; Ansell, N., Klocker, N., Skelton, T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 329–346. ISBN 978-981-4585-53-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolo, M.G.; Servidio, R.; Palermiti, A.L.; Nappa, M.R.; Costabile, A. Pro-environmental behaviors and well-being in adolescence: The mediating role of place attachment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venhoeven, L.A.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Why going green feels good. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, J.; Terlau, W. Education for sustainable development and meaningfulness: Evidence from the questionnaire of eudaimonic well-being from German students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures 2017, 94, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D. Children’s constructive climate change engagement: Empowering awareness, agency, and action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Howell, R.T. Moderators and mediators of pro-social spending and well-being: The influence of values and psychological need satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 69, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, O.S.; Rowland, L.A.; van Lissa, C.J.; Zlotowitz, S.; McAlaney, J.; Whitehouse, H. Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 76, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, S.; Sanson, A.V. The Australian Temperament Project: The First 30 Years. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/atp30.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Sanson, A.V.; Wachs, T.D.; Koller, S.H.; Salmela-Aro, K. Young people and climate change: The role of developmental science. In Developmental Science and Sustainable Development Goals for Children and Youth; Verma, S., Petersen, A.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 115–137. ISBN 978-3-319-96591-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Consumers’ sustainable purchase behaviour: Modeling the impact of psychological factors. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, H.; Loy, L.S. What drives pro-environmental activism of young people? A survey study on the Fridays for Future movement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.G. Social movements and the politics of care: Empathy, solidarity and eviction blockades. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2020, 19, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.R.; Garrett, M.K. Preschoolers’ moral judgments of environmental harm and the influence of perspective taking. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithoxoidou, L.S.; Georgopoulos, A.D.; Dimitriou, A.T.; Xenitidou, S.C. “Trees have a soul too!” Developing empathy and environmental values in early childhood. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2017, 5, 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, H.; Hudders, L.; van de Sompel, D.; Cauberghe, V. Motivating children to become green kids: The role of victim framing, moral emotions, and responsibility on children’s pro-environmental behavioral intent. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H.; Mican, F. Childhood pet ownership, attachment to pets, and subsequent meat avoidance. The mediating role of empathy toward animals. Appetite 2014, 79, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Salisch, M.; Voltmer, K. A daily breathing practice bolsters girl’s pro-social behavior and third and fourth grader’s supportive peer relationships: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuba, M.K.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; McElroy, T.; Katahoire, A. Effectiveness of a SEL/mindfulness program on Northern Ugandan children. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 9, S113–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Oberle, E.; Lawlor, M.S.; Abbott, D.; Thomson, K.; Oberlander, T.F.; Diamond, A. Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bristow, J.; Bell, R.; Wamsler, C. Reconnection: Meeting the Climate Crisis Inside Out; Mindfulness Initiative: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 1913353060. [Google Scholar]

- Ericson, T.; Kjønstad, B.G.; Barstad, A. Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.L.; Griffiths, K.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Foulkes, L.; Parker, J.; Dalgleish, T. Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2018, 60, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U.; Grossman, P. Meditating for the planet: Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on sustainable consumption behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1012–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainability: Correlation or causation? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.M.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, I.J.; Raymond, C.M. Positive psychology perspectives on social values and their application to intentionally delivered sustainability interventions. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, T.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness training at school: A way to engage adolescents with sustainable consumption? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalón, C.; Montero-Marin, J.; Modrego-Alarcón, M.; Gascón, S.; Navarro-Gil, M.; Barceló-Soler, A.; Delgado-Suárez, I.; García-Campayo, J. Implementing a training program to promote mindful, empathic, and pro-environmental attitudes in the classroom: A controlled exploratory study with elementary school students. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4422–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrable, A.; Booth, D.; Adams, D.; Beauchamp, G. Enhancing nature connection and positive affect in children through mindful engagement with natural environments. IJERPH 2021, 18, 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiermann, U.B.; Sheate, W.R. How does mindfulness affect pro-environmental behaviors? A qualitative analysis of the mechanisms of change in a sample of active practitioners. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2997–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, B.P.; Romano, A.; Kateman, S.; Nori, R. Less is more: Mindfulness, portion size, and candy eating pleasure. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 103, 104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhoeven, L.A.; Bolderdijk, J.; Steg, L. Explaining the paradox: How pro-environmental behaviour can both thwart and foster well-being. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F.B.; Veroff, J. Savoring: A New Model of Positive Experience, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781315088426. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Schimmack, U.; Diener, E. Pleasures and subjective well-being. Eur. J. Pers. 2001, 15, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, G.A.; Benfield, J.; Bell, P.A. Women engaging the natural world: Motivation for sensory pleasure may account for gender differences. Ecopsychology 2010, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.J.; Given, L.M.; Martin, J.M.; Hochuli, D.F. Urban children’s connections to nature and environmental behaviors differ with age and gender. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, I.; Kim, S.; Kim, M. The relative importance of values, social norms, and enjoyment-based motivation in explaining pro-environmental product purchasing behavior in apparel Domain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, J.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Keinonen, T. Examining the relationships between factors influencing environmental behaviour among university students. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K.C.; Kringelbach, M.L. Building a neuroscience of pleasure and well-being. Psychol. Well Being 2011, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett-Cheetham, E.; Williams, L.A.; Bednall, T.C. A differentiated approach to the link between positive emotion, motivation, and eudaimonic well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, S.S.; Niles, B.L.; Park, C.L. A mindfulness model of affect regulation and depressive symptoms: Positive emotions, mood regulation expectancies, and self-acceptance as regulatory mechanisms. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Morgan, J. Mental health recovery and nature: How social and personal dynamics are important. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.L.; Waltz, J.A. Mindfulness, self-esteem, and unconditional self-acceptance. J. Rat.-Emo. Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2008, 26, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Bragg, R.; Pretty, J.; Roberts, J.; Wood, C. The Wilderness Expedition. J. Exp. Educ. 2016, 39, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. The influence mechanism of environmental anxiety on pro-environmental behaviour: The role of self-discrepancy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, P.; Garcia, O.F.; Garcia, F.; Zacares, J.J.; Camino, C. Self and nature: Parental socialization, self-esteem, and environmental values in Spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresner, M.; Gill, M. Environmental education at summer nature camp. J. Environ. Educ. 1994, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, J.R.; McKay, M.T. Self-efficacy and well-being in adolescents: A comparative study using variable and person-centered analyses. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, A.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Saloranta, S. Participatory school experiences as facilitators for adolescents’ ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrasin, O.; Crettaz von Roten, F.; Butera, F. Who’s to Act? Perceptions of intergenerational obligation and pro-environmental behaviours among youth. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.O.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G.; Fisher, J.O.; Anderson, C.B.; Nicklas, T.A. The impact of child care providers’ feeding on children’s food consumption. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sella, E.; Bolognesi, M.; Bergamini, E.; Mason, L.; Pazzaglia, F. Psychological benefits of attending forest school for preschool children: A systematic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 35, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wu, Z. They can and will: Preschoolers encourage pro-environmental behavior with rewards and punishments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, M.; Jerman, J.; Anžlovar, U.; Torkar, G. Preschool children’s understanding of pro-environmental behaviours: Is It too hard for them? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 5554–5571. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, E.A.; Murray, R. A Marvellous Opportunity for Children to Learn: A Participatory Evaluation of Forest School in England and Wales; Forest Research: Surrey, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sieg, A.-K.; Dreesmann, D. Promoting Pro-Environmental BEEhavior in School. Factors Leading to Eco-Friendly Student Action. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, D. Outdoor school for all: Reconnecting children to nature. In EarthEd: Rethinking Education on a Changing Planet; Worldwatch Insitute, Ed.; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 23–33. ISBN 978-1-61091-873-2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).