The Decision-Making and Moderator Effects of Transaction Costs, Service Satisfaction, and the Stability of Agricultural Productive Service Contracts: Evidence from Farmers in Northeast China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework Construction

3. Data and Method

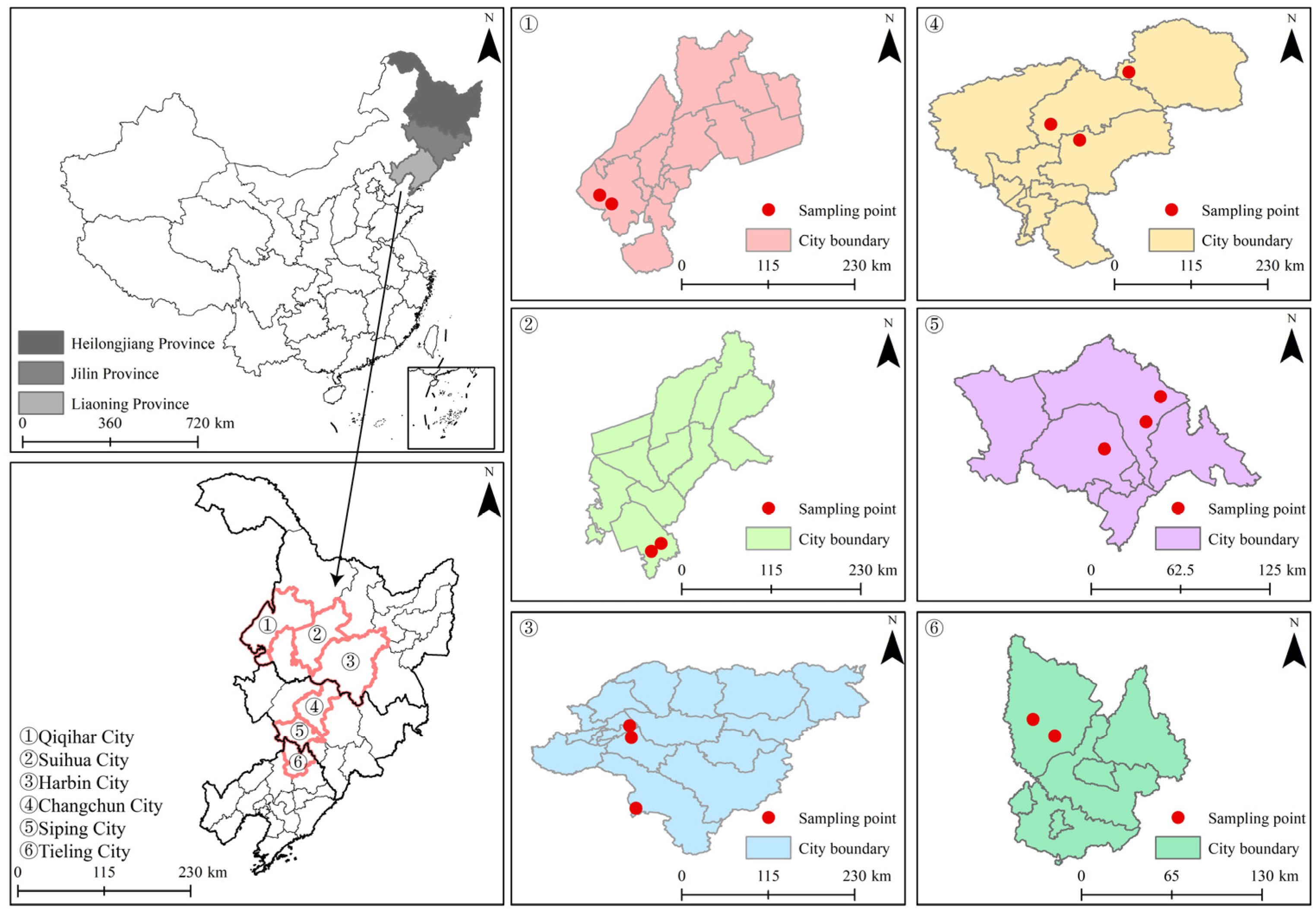

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Method

3.3.1. Mvprobit Model

3.3.2. Variable Selection

4. Result

4.1. The Impact of Transaction Costs on the Stability of Farmers’ Agricultural Productive Service Contracts

4.1.1. The Impact of Transaction Costs on Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts for Agricultural Productive Services

4.1.2. The Impact of Transaction Costs on Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate in Agricultural Productive Service Contracts

4.1.3. The Impact of the Characteristics of Rural Households’ Production and Operation on the Stability of Farmers’ Agricultural Production Service Contracts

4.2. The Moderating Effect of Service Satisfaction on the Stability of Farmers’ Agricultural Productive Service Contracts

4.2.1. Moderating Analysis of the Impact of Service Satisfaction on Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts and Long-Term Cooperation for Agricultural Productive Services

4.2.2. Mediation Analysis of the Impact of Service Satisfaction on the Stability of Different Service Types in Farmers’ Agricultural Productivity

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution of This Study

5.2. Shortcomings of the Study

5.3. Future Research Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y. The Challenges and Strategies of Food Security under Rapid Urbanization in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Fan, X.; Jin, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Oenema, O.; Velthof, G.; Hu, C.; Ma, L. Relocate 10 Billion Livestock to Reduce Harmful Nitrogen Pollution Exposure for 90% of China’s Population. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Reflections on China’s Food Security and Land Use Policy under Rapid Urbanization. Land. Use Policy 2021, 109, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuneng, D.; Youliang, X.; Leiyong, Z.; Shufang, S. Can China’s Food Production Capability Meet Her Peak Food Demand. in the Future? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, Y. China’s Food Security Challenge: Effects of Food Habit Changes on Requirements for Arable Land and Water. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Han, Q. Food Security of Mariculture in China: Evolution, Future Potential and Policy. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Zhao, C.; Ullah, W.; Ahmad, R.; Waseem, M.; Zhu, J. Towards Sustainable Farm Production System: A Case Study of Corn Farming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Fang, F.; Che, X.; Chen, M. Evaluation of Urban-Rural Difference and Integration Based on Quality of Life. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, H.; Liao, L.; Tu, S.; Li, T. Land Use Transitions and Urban-Rural Integrated Development: Theoretical Framework and China’s Evidence. Land. Use Policy 2020, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of Urban-Rural Integration Level and Its Spatial Differentiation in China in the New Century. Habitat. Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Ning, G.; Rong, Z. Destination Homeownership and Labor Force Participation: Evidence from Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. J. Hous. Econ. 2022, 55, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, P.; Peng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wan, J. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Rural Labor Migration in China: Evidence from the Migration Stability under New-Type Urbanization. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Squires, V.R. Integration of Rural and Urban Society in China and Implications for Urbanization, Infrastructure, Land and Labor in the New Era. SAJSSE 2019, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Yu Benjamin, F. Labor Mobility Barriers and Rural-Urban Migration in Transitional China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 53, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Bao, H.X.H.; Zhang, Z. Off-Farm Employment and Agricultural Land Use Efficiency in China. Land. Use Policy 2021, 101, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, H. Intentions of Farmers to Renew Productive Agricultural Service Contracts Using the Theory of Planned Behavior: An Empirical Study in Northeastern China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, H. Does the Agricultural Productive Service Embedded Affect Farmers’ Family Economic Welfare Enhancement? An Empirical Analysis in Black Soil Region in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Long, H.; Tang, L.; Tu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y. Analysis of the Spatial Variations of Determinants of Agricultural Production Efficiency in China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ke, J.; Su, Y. What Drives Smallholders to Utilize Socialized Agricultural Services for Farmland Scale Management? Insights from the Perspective of Collective Action. Land 2022, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioliou, E.; Willcocks, L.; Liu, X. Researching IT Multi-Sourcing and Opportunistic Behavior in Conditions of Uncertainty: A Case Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdin, E.; Cebe, M.; Akkaya, K.; Solak, S.; Bulut, E.; Uluagac, S. A Bitcoin Payment Network with Reduced Transaction Fees and Confirmation Times. Comput. Netw. 2020, 172, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Are There Too Many Farms in the World? Labor-Market Transaction Costs, Machine Capacities and Optimal Farm Size; NBER Working Papers; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.; Vink, N. The Development of Vegetable Enterprises in the Presence of Transaction Costs among Farmers in Omsati Region of Namibia: An Assessment. J. Agric. Food Res. 2020, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A. Transaction Cost Theory: Past, Present and Future. AMS Rev. 2019, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.W.E.; Berg, C.; Davidson, S.; Potts, J. On Coase and COVID-19. Eur. J. Law. Econ. 2022, 54, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Antecedents and Outcomes of Employee Empowerment Practices: A Theoretical Extension with Empirical Evidence. Human. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldstad, Ø.D.; Snow, C.C. Business Models and Organization Design. Long. Range Plan. 2018, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lin, P.; Song, F. Property Rights Protection and Corporate R&D: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 93, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Torre, A.; Ehrlich, M. The impact of Chinese government promoted homestead transfer on labor migration and household’s well-being: A study in three rural areas. J. Asian Econ. 2023, 86, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-T.; Chen, P.-C.; Su, C.-Y.; Chao, C. Behavioral Intention to Undertake Health Examinations: Transaction Cost Theory and Social Exchange Theory. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2019, 11, 100–112. Available online: https://www.ijoi-online.org/attachments/article/134/0922%20 (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Dias, M.F.; Silva, A.C.; Nunes, L.J.R. Transaction Cost Theory: A Case Study in the Biomass-to-Energy Sector. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2021, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Zhang, A. Effect of Transaction Rules on Enterprise Transaction Costs Based on Williamson Transaction Cost Theory in Nanhai, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Lin, Y.-L.; Hou, H.-C. What Drives Consumers to Adopt a Sharing Platform: An Integrated Model of Value-Based and Transaction Cost Theories. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Economics of Transaction Costs Saving Forestry. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 36, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D.R. Customer Satisfaction, Market Share, and Profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Johnson, L.W.; Spreng, R.A. Modeling the Determinants of Customer Satisfaction for Business-to-Business Professional Services. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Z.; Ma, W.; Valentinov, V. The Effect of Cooperative Membership on Agricultural Technology Adoption in Sichuan, China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 62, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, F.K.; Joshua, M.; Ngongondo, C. Determinants of Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricul tural Practices in Zomba, Eastern Malawi. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Digital economy and farmers’ income inequality—A quasi-natural experiment based on the “broadband China” strategy. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. Social capita’s role in mitigating economic vulnerability: Understanding the impact of income disparities on farmers’ livelihoods. World Dev. 2024, 177, 106515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. Neighborhood Does Matter: Farmers’ Local Social Interactions and Land Rental Behaviors in China. Land 2024, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Linderholm, H.W.; Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, G. Climatic Causes of Maize Production Loss under Global Warming in Northeast China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, D. Evaluation and Driving Factors of City Sustainability in Northeast China: An Analysis Based on Interaction among Multiple Indicators. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuxi, G. A Study on the Conservation of Soil Fauna Diversity in the Black Soil Agroecosystem, Northeast China; Changchun University: Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mwinkom, F.X.K.; Damnyag, L.; Abugre, S.; Alhassan, S.I. Factors Influencing Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in North-Western Ghana: Evidence of Farmers in the Black Volta Basin in Upper West Region. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, M.; Ren, B.; Zou, Y.; Lv, T. Understanding Farmers’ Willingness in Arable Land Protection Cooperation by Using fsQCA: Roles of Perceived Benefits and Policy Incentives. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 68, 126234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koech, K.K.; Chege, C.G.K.; Bett, H. Which Food Outlets Are Important for Nutrient-Dense-Porridge-Flour Access by the Base-of-the-Pyramid Consumers? Evidence from the Informal Kenyan Settlements. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Duan, K.; Zhang, W. The Impact of Internet Use on Farmers’ Land Transfer under the Framework of Transaction Costs. Land 2023, 12, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoro, J.T.; Mudhara, M.; Chimonyo, M. Farmers’ choice of cattle marketing channels under transaction cost in rural South Africa: A multinomial logit model. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2015, 32, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Chen, H. The Farmers’ Willingness to Enter the Collective Construction Land. Market from the Perspective of Transaction Cost Economics: An Empirical Analysis of Nanhai District. In Proceedings of the 2019 5Th International Conference On Environmental Science and Material Application 2020, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–13 November 2019; Volume 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Ma, W. Trust, transaction costs, and contract enforcement: Evidence from apple farmers in China. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Song, H. Research on Negotiation Game of Supply-sale Contract of Agricultural Products Based on Bargaining Model. In Proceedings of the 2013 Sixth International Conference On Business Intelligence and Financial Engineering (Bife), Hangzhou, China, 14–16 November 2013; pp. 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, H. The Effect of Uncertainty of Riskson Farmers’ Contractual Choice Behavior for Agricultural Productive Services: An Empirical Analysis from the Black Soil in Northeast China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Delgado, M.S. The Transition to Modern Agriculture: Contract Farming in Developing Economies. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, J. The Vertical Division of Agricultural Industrial Chain and Its Selection of Institutional Arrangements: From the View of Transaction Cost Economics. In Proceedings of the International Asia Conference on Industrial Engineering and Management Innovation (IEMI2012) Proceedings; Qi, E., Shen, J., Dou, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1349–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Xinyue, L.; Li, Z. Agricultural Contract Arrangement: Farmers’ Risk Attitude and Contract Choice Decision. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2020, 20, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijian, C.; Jie, W. A Study of the Influence of Village Cadre Identity on Agricultural Land Transfer Contracts and the Diffusion Effect: An Example of Duration. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. 2022, 5, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Harbin | Suihua | Qiqihar | Changchun | Siping | Tieling | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | ||||||||||

| Gender | Male | Freq | 64 | 114 | 133 | 172 | 170 | 191 | 844 | |

| Prop | 7.58 | 13.51 | 15.76 | 20.38 | 20.14 | 22.63 | 100 | |||

| Female | Freq | 1 | 3 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 19 | 49 | ||

| Prop | 2.04 | 6.12 | 2.04 | 42.86 | 8.16 | 38.78 | 100 | |||

| Education | Illiteracy | Freq | 7 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 35 | |

| Prop | 20 | 20 | 8.57 | 22.86 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 100 | |||

| Primary school | Freq | 20 | 71 | 57 | 85 | 77 | 83 | 393 | ||

| Prop | 5.09 | 18.07 | 14.50 | 21.63 | 19.59 | 21.12 | 100 | |||

| Junior high school | Freq | 33 | 33 | 68 | 82 | 71 | 109 | 396 | ||

| Prop | 8.33 | 8.33 | 17.17 | 20.71 | 17.93 | 27.53 | 100 | |||

| High school and above | Freq | 5 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 21 | 13 | 69 | ||

| Prop | 7.25 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 26.09 | 30.43 | 18.84 | 100 | |||

| Family size | 1–2 | Freq | 26 | 44 | 33 | 49 | 43 | 66 | 261 | |

| Prop | 9.96 | 16.86 | 12.64 | 18.77 | 16.48 | 25.29 | 100 | |||

| 3–4 | Freq | 28 | 38 | 69 | 73 | 70 | 97 | 375 | ||

| Prop | 7.47 | 10.13 | 18.40 | 19.47 | 18.67 | 25.87 | 100 | |||

| More than 5 | Freq | 11 | 35 | 32 | 71 | 61 | 47 | 257 | ||

| Prop | 4.28 | 13.62 | 12.45 | 27.63 | 23.74 | 18.29 | 100 | |||

| Do you have non-agricultural income? | No | Freq | 30 | 44 | 73 | 69 | 56 | 75 | 347 | |

| Prop | 8.65 | 12.68 | 21.04 | 19.88 | 16.14 | 21.61 | 100 | |||

| Yes | Freq | 35 | 73 | 61 | 124 | 118 | 135 | 546 | ||

| Prop | 6.41 | 13.37 | 11.17 | 22.71 | 21.61 | 24.73 | 100 | |||

| Different types APS | Partial production process services | Freq | 35 | 80 | 124 | 163 | 170 | 82 | 654 | |

| Prop | 5.35 | 12.23 | 18.96 | 24.92 | 25.99 | 12.54 | 100 | |||

| Full trusteeship service | Freq | 30 | 37 | 10 | 30 | 4 | 128 | 239 | ||

| Prop | 12.55 | 15.48 | 4.18 | 12.55 | 1.67 | 53.56 | 100 | |||

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Description | Mean | S.D. | MIN | MAX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Farmers’ willingness to renew contracts (C1a) | 0 = No; 1 = Yes | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | |

| Farmers’ long-term willingness to cooperate (C1b) | 0 = No; 1 = Yes | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Core explanatory variables | Information Cost (A1) | The relationship between farmers and service providers (a11) | 1 = Very Good; 2 = Good; 3 = General; 4 = Poor; 5 = Very Poor | 2.36 | 0.65 | 1 | 5 |

| Trust between farmers and service providers (a12) | 1 = Very Good; 2 = Good; 3 = General; 4 = Poor; 5 = Very Poor | 2.09 | 0.59 | 1 | 5 | ||

| The reasonableness of the price charged (a13) | 1 = Very Good; 2 = Good; 3 = General; 4 = Poor; 5 = Very Poor | 2.34 | 0.68 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Farmers’ understanding of service content and term (a14) | 1 = Very Good; 2 = Good; 3 = General; 4 = Poor; 5 = Very Poor | 2.28 | 0.65 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Negotiation Cost (A2) | Farmers’ current contract type selection (a21) | 1 = Oral; 2 = Written | 1.26 | 0.44 | 1 | 2 | |

| Service organization guarantees output (a21) | 1 = No; 2 = Yes | 1.23 | 0.42 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Payment methods for agricultural productive services (a21) | 1 = Full; 2 = Installment | 1.22 | 0.42 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Execution Cost (A3) | The length of waiting time from appointment to service anticipated by farmers (a31) | 1 = Very Not Long; 2 = Not Long; 3 = Average; 4 = Long; 5 = Very Long | 2.17 | 0.59 | 1 | 5 | |

| Time taken to contact service providers by farmers (a31) | 1 = Very Little; 2 = Not Much; 3 = Average; 4 = A Lot; 5 = Very Much | 2.20 | 0.62 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Degree of difficulty farmers encounter in contacting agricultural production services (a33) | 1 = Very Easy; 2 = Easy; 3 = Average; 4 = Not Easy; 5 = Very Difficult | 2.14 | 0.61 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Service Satisfaction (B1) | Farmers’ satisfaction with service providers’ service (b11) | 1 = Very Poor; 2 = Poor; 3 = General; 4 = Good; 5 = Very Good | 3.86 | 0.57 | 1 | 5 | |

| Satisfaction with current services amongst farmers (b12) | 1 = Very Poor; 2 = Poor; 3 = General; 4 = Good; 5 = Very Good = 5 | 3.83 | 0.62 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Service attitude satisfaction amongst farmers (b13) | 1 = Very Poor; 2 = Poor; 3 = General; 4 = Good; 5 = Very Good | 4.02 | 0.45 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Control variables | Individual Characteristics | Gender | 1 = Male; 2 = Female | 1.05 | 0.23 | 1 | 2 |

| Education | Years | 7.09 | 2.78 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Family Characteristics | Machinery | 1 = With Machinery; 0 = Without Machinery | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Fragmentation | Number of land parcels | 5.23 | 4.86 | 1 | 55 | ||

| Terrain | 0 = Slope or Depression; 1 = Flat Land | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Aging | The ratio of the number of 55-year-old men | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Population | Numbers | 35.04 | 37.70 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Land | Numbers | 40.86 | 45.77 | 2.5 | 358 | ||

| Farmscale | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | Y | 0.40 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Non-farm | Ratio of household non-farm income | 2.10 | 0.51 | 0 | 4.77 | ||

| Income level | 1 = Upper; 2 = Medium; 3 = Lower | 1.88 | 0.76 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Risk Factors | Disaster | The number of local natural disasters in the past five years. | 1.92 | 1.32 | 0 | 10 | |

| Identify Variables | Risk | 0 = Familiar; 1 = Stranger | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | |

| Region Dummy Variable | Province | 1 = Heilongjiang Province; 2 = Jilin Province; 3 = Liaoning Province | 1.05 | 0.23 | 1 | 3 | |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts | Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate | Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts | Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate | |||||

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| A1 | −0.3048 *** | 0.0600 | −0.2112 *** | 0.0584 | ||||

| A2 | 0.1539 *** | 0.0522 | 0.1596 *** | 0.0466 | ||||

| A3 | −0.0245 | 0.0486 | −0.1037 ** | 0.0475 | ||||

| B1 | 0.3562 *** | 0.0630 | 0.2870 *** | 0.0622 | 0.3662 *** | 0.0656 | 0.2946 *** | 0.0663 |

| a11 | −0.3442 *** | 0.0903 | −0.4729 *** | 0.0901 | ||||

| a12 | −0.1484 ** | 0.0763 | −0.1063 ** | 0.0585 | ||||

| a13 | −0.2224 *** | 0.0770 | −0.2160 *** | 0.0763 | ||||

| a14 | −0.0650 | 0.0833 | 0.0269 | 0.0819 | ||||

| a21 | 0.4889 ** | 0.2022 | 0.1742 ** | 0.0783 | ||||

| a22 | 0.1448 | 0.2050 | 0.1976 | 0.1834 | ||||

| a23 | 0.1811 ** | 0.0935 | 0.1234 ** | 0.0679 | ||||

| a31 | −0.0901 | 0.0898 | −0.2166 ** | 0.0940 | ||||

| a32 | −0.1261 | 0.0842 | −0.1789 ** | 0.0831 | ||||

| a36 | −0.1339 | 0.0893 | −0.2919 *** | 0.0893 | ||||

| Machinery | −0.0199 | 0.1103 | −0.1122 | 0.1037 | −0.0044 | 0.1115 | −0.0937 | 0.1057 |

| Fragmentation | 0.0068 | 0.0128 | 0.0102 | 0.0116 | 0.0041 | 0.0130 | 0.0067 | 0.0119 |

| Terrain | 0.2821 *** | 0.1016 | 0.2096 * | 0.1095 | 0.2930 *** | 0.1127 | 0.1944 * | 0.1118 |

| Aging | −0.0003 | 0.1481 | −0.3409 ** | 0.1420 | −0.0191 | 0.1497 | −0.3691 ** | 0.1448 |

| Disaster | −0.0076 | 0.0373 | −0.0988 *** | 0.0357 | −0.0032 | 0.0381 | −0.1119 *** | 0.0366 |

| Risk | −0.6006 *** | 0.1411 | −0.3937 *** | 0.1411 | −0.5727 *** | 0.1454 | −0.2663 ** | 0.1360 |

| Land | −0.0421 | 0.0877 | −0.1001 | 0.0810 | −0.0309 | 0.0887 | −0.1074 | 0.0827 |

| Farmscale | −0.0415 | 0.1239 | −0.0268 | 0.1183 | −0.0192 | 0.1261 | −0.0175 | 0.1215 |

| Gender | 0.0808 | 0.2117 | 0.2023 | 0.1994 | 0.0026 | 0.2155 | 0.0801 | 0.2051 |

| Education | 0.0207 | 0.0175 | 0.0185 | 0.0165 | 0.0194 | 0.0178 | 0.0149 | 0.0170 |

| Population | 0.0233 | 0.0411 | −0.0113 | 0.0396 | 0.0271 | 0.0416 | −0.0036 | 0.0405 |

| Non-farm | −0.0013 | 0.0014 | −0.0010 | 0.0014 | −0.0013 | 0.0014 | −0.0010 | 0.0014 |

| Income level | 0.0524 | 0.0973 | 0.1151 | 0.0926 | 0.0834 | 0.0990 | 0.1581 | 0.0955 |

| Province | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Atrho21 | 0.6502 *** (0.0658) | 0.6424 *** (0.0678) | ||||||

| 0.5718 *** (0.0442) | 0.5667 *** (0.0461) | |||||||

| Log likelihood | −969.4494 | −943.2701 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| N | 893 | 893 | ||||||

| Variable | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts | Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate | |||

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| A1 | −0.3016 *** | 0.0618 | −0.2235 *** | 0.0596 |

| A2 | 0.1540 *** | 0.0542 | 0.1825 *** | 0.0493 |

| A3 | −0.0494 | 0.0496 | −0.0963 ** | 0.0481 |

| B1 | 0.4023 *** | 0.0687 | 0.3529 *** | 0.0693 |

| A1*B1 | 0.0593 | 0.0475 | 0.1579 *** | 0.0486 |

| A2*B1 | 0.1541 ** | 0.0692 | 0.1138 ** | 0.0528 |

| A3*B1 | 0.1228 *** | 0.0460 | 0.0702 * | 0.0411 |

| Machinery | −0.0305 | 0.1116 | −0.1043 | 0.1048 |

| Fragmentation | 0.0077 | 0.0130 | 0.0104 | 0.0117 |

| Terrain | 0.2808 ** | 0.1127 | 0.2292 ** | 0.1106 |

| Aging | −0.0010 | 0.1496 | −0.3472 ** | 0.1438 |

| Disaster | −0.0123 | 0.0378 | −0.0933** | 0.0363 |

| Risk | −0.6269 *** | 0.1441 | −0.3885 *** | 0.1433 |

| Land | −0.0396 | 0.0883 | −0.1012 | 0.0814 |

| Farmscale | −0.0453 | 0.1256 | −0.0434 | 0.1195 |

| Gender | 0.0549 | 0.2118 | 0.2171 | 0.2027 |

| Education | 0.0185 | 0.0176 | 0.0195 | 0.0166 |

| Population | 0.0271 | 0.0414 | −0.0125 | 0.0401 |

| Non-farm | −0.0015 | 0.0014 | −0.0010 | 0.0014 |

| Income level | 0.0397 | 0.0984 | 0.0985 | 0.0935 |

| Province | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Atrho21 | 0.6504 *** (0.0662) | |||

| 0.5719 *** (0.0445) | ||||

| Log likelihood | −956.5148 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | |||

| N | 893 | |||

| Variable | Model 4: Adjustment Estimates of Service Satisfaction in Some Links | Model 5: Full Managed Service Satisfaction Adjustment Estimate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts | Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate | Farmers’ Willingness to Renew Contracts | Farmers’ Long-Term Willingness to Cooperate | |||||

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| A1 | −0.2219 *** | 0.0733 | −0.1516 ** | 0.0737 | −0.4313 *** | 0.1067 | −0.3505 *** | 0.1010 |

| A2 | −0.1349 | 0.1528 | −0.0662 | 0.1446 | 0.2973 *** | 0.1100 | 0.2915 *** | 0.0971 |

| A3 | −0.0223 | 0.0589 | −0.1001 * | 0.0584 | −0.0701 | 0.0770 | −0.1550 ** | 0.0728 |

| B1 | 0.5683 ** | 0.1747 | 0.3372 ** | 0.1412 | 0.3345 *** | 0.1257 | 0.6359 *** | 0.1471 |

| A1*B1 | 0.0695 | 0.0584 | 0.1131 * | 0.0645 | 0.0023 | 0.0771 | 0.2971 *** | 0.0804 |

| A2*B1 | 0.3403 | 0.2573 | 0.1273 | 0.2065 | 0.1972 ** | 0.0959 | 0.1596 * | 0.0876 |

| A3*B1 | 0.1279 ** | 0.0620 | 0.1119 * | 0.0614 | 0.1436 ** | 0.0668 | 0.1511 ** | 0.0657 |

| Machinery | −0.1413 | 0.1294 | −0.0608 | 0.1260 | −0.1629 | 0.2285 | −0.0275 | 0.1995 |

| Fragmentation | 0.0085 | 0.0140 | 0.0096 | 0.0130 | 0.0139 | 0.0194 | 0.0384 | 0.0205 |

| Terrain | 0.1573 * | 0.0917 | 0.1246 | 0.1320 | 0.4736 *** | 0.1793 | 0.1927 | 0.1707 |

| Aging | −0.1673 | 0.1729 | −0.4689 *** | 0.1730 | 0.2250 | 0.2598 | 0.2085 | 0.2373 |

| Disaster | −0.0014 | 0.0447 | −0.1280 *** | 0.0441 | −0.0123 | 0.0655 | −0.0840 | 0.0617 |

| Risk | −0.8074 *** | 0.1763 | −0.7206 *** | 0.1974 | −0.4137 * | 0.2261 | −0.0252 | 0.2123 |

| Land | −0.0566 | 0.0993 | −0.1511 | 0.0960 | −0.0349 | 0.1659 | −0.0664 | 0.1472 |

| Farmscale | −0.0471 | 0.1519 | −0.1125 | 0.1513 | 0.0934 | 0.2159 | 0.0977 | 0.1957 |

| Gender | 0.3112 | 0.2553 | 0.3731 | 0.2430 | −0.1475 | 0.3892 | −0.1980 | 0.3718 |

| Education | 0.0215 | 0.0200 | 0.0186 | 0.0193 | 0.0304 | 0.0337 | 0.0059 | 0.0315 |

| Population | 0.0461 | 0.0460 | −0.0132 | 0.0460 | −0.0218 | 0.0822 | −0.0439 | 0.0750 |

| Non-farm | −0.0008 | 0.0015 | −0.0005 | 0.0015 | −0.0039 | 0.0033 | −0.0007 | 0.0030 |

| Income level | 0.0564 | 0.1144 | 0.1185 | 0.1120 | 0.0158 | 0.1773 | 0.0828 | 0.1559 |

| Province | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Atrho21 | 0.6709 *** (0.0815) | 06999 *** (0.1172) | ||||||

| 0.5856 *** (0.0536) | 0.6043 *** (0.0744) | |||||||

| Log likelihood | −720.5194 | −322.7582 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| N | 654 | 342 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, Y.; Liu, H.; Chai, Z.; Wang, Z. The Decision-Making and Moderator Effects of Transaction Costs, Service Satisfaction, and the Stability of Agricultural Productive Service Contracts: Evidence from Farmers in Northeast China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114371

Xue Y, Liu H, Chai Z, Wang Z. The Decision-Making and Moderator Effects of Transaction Costs, Service Satisfaction, and the Stability of Agricultural Productive Service Contracts: Evidence from Farmers in Northeast China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114371

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Ying, Hongbin Liu, Zhenzhen Chai, and Zimo Wang. 2024. "The Decision-Making and Moderator Effects of Transaction Costs, Service Satisfaction, and the Stability of Agricultural Productive Service Contracts: Evidence from Farmers in Northeast China" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114371