How to Enhance Consumer’s Engagement with Returnable Cup Services? A Study of a Strategic Approach to Achieve Environmental Sustainability

Abstract

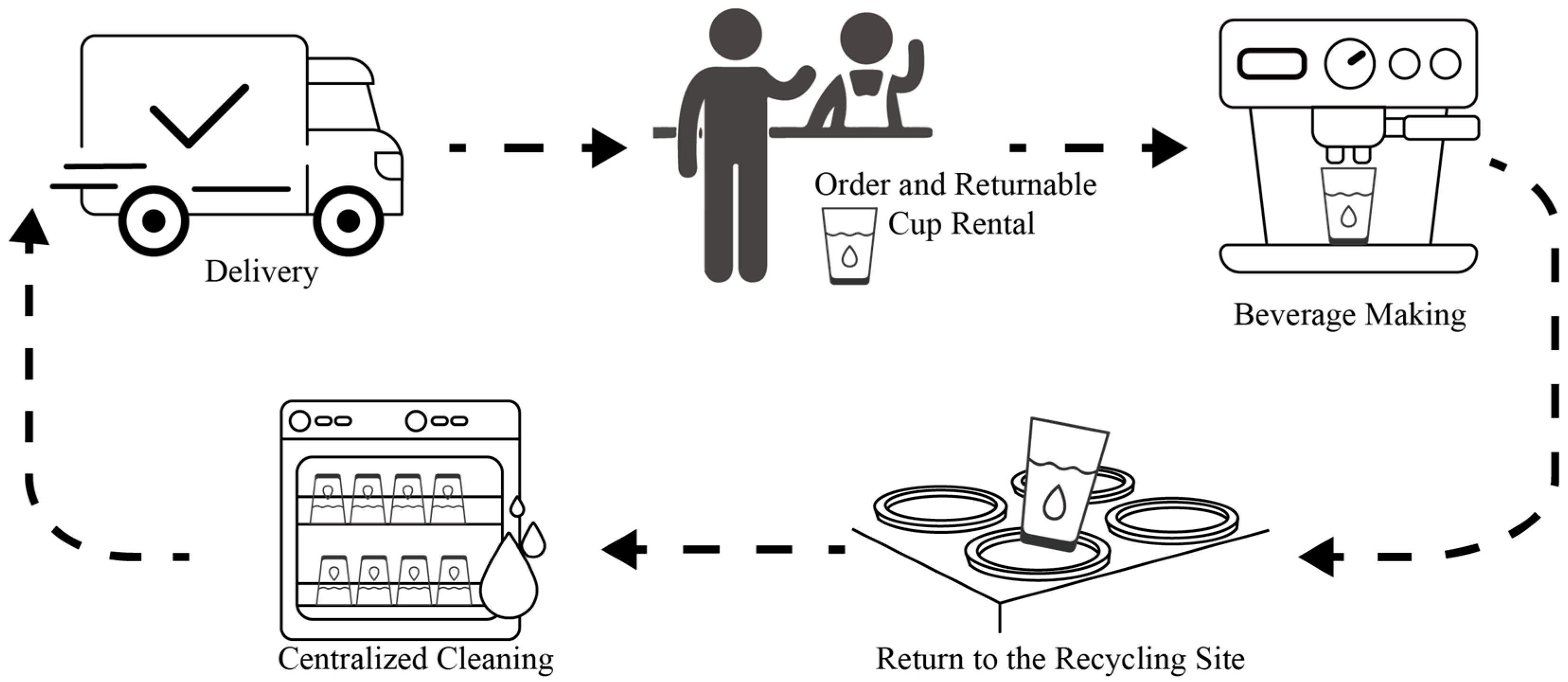

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NAM

2.2. Convenience of Use (CU)

2.3. Environmental Concern

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Analysis

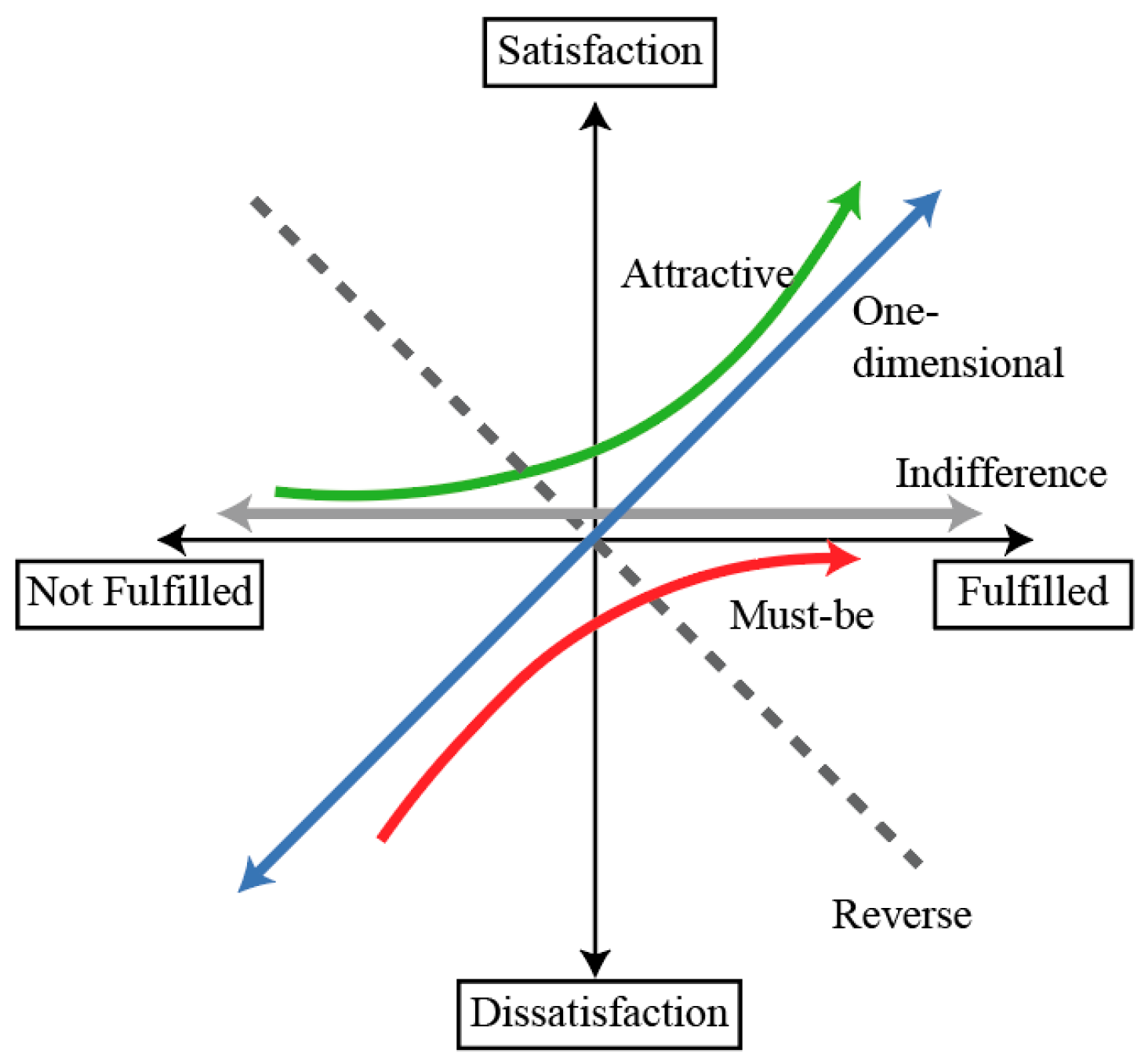

3.4. Kano Model

- Attractive qualities (A): These attributes are initially perceived as insignificant, meaning their presence or absence does not notably affect satisfaction. However, when the performance of these attributes becomes significant, satisfaction is greatly enhanced. Essentially, these qualities have the potential to delight customers when present.

- Must-be qualities (M): Must-be qualities represent fundamental attributes that customers expect as a minimum requirement. When these qualities perform at a satisfactory level, satisfaction remains unchanged, but failure to meet expectations can lead to significant dissatisfaction.

- One-dimensional qualities (O): One-dimensional qualities exhibit a linear relationship with satisfaction. Higher performance levels lead to increased satisfaction, while lower performance levels result in decreased satisfaction. These qualities typically align with customer expectations and form the basis of competitive advantage.

- Indifference: Indifference signifies that the quality attribute is unaffected by changes in performance. Whether the attribute performs well or poorly, it has little to no impact on overall satisfaction.

- Reversal: Reversal qualities represent a unique scenario where high performance actually diminishes satisfaction. In other words, exceeding expectations in these areas can lead to reduced satisfaction levels.

4. Results

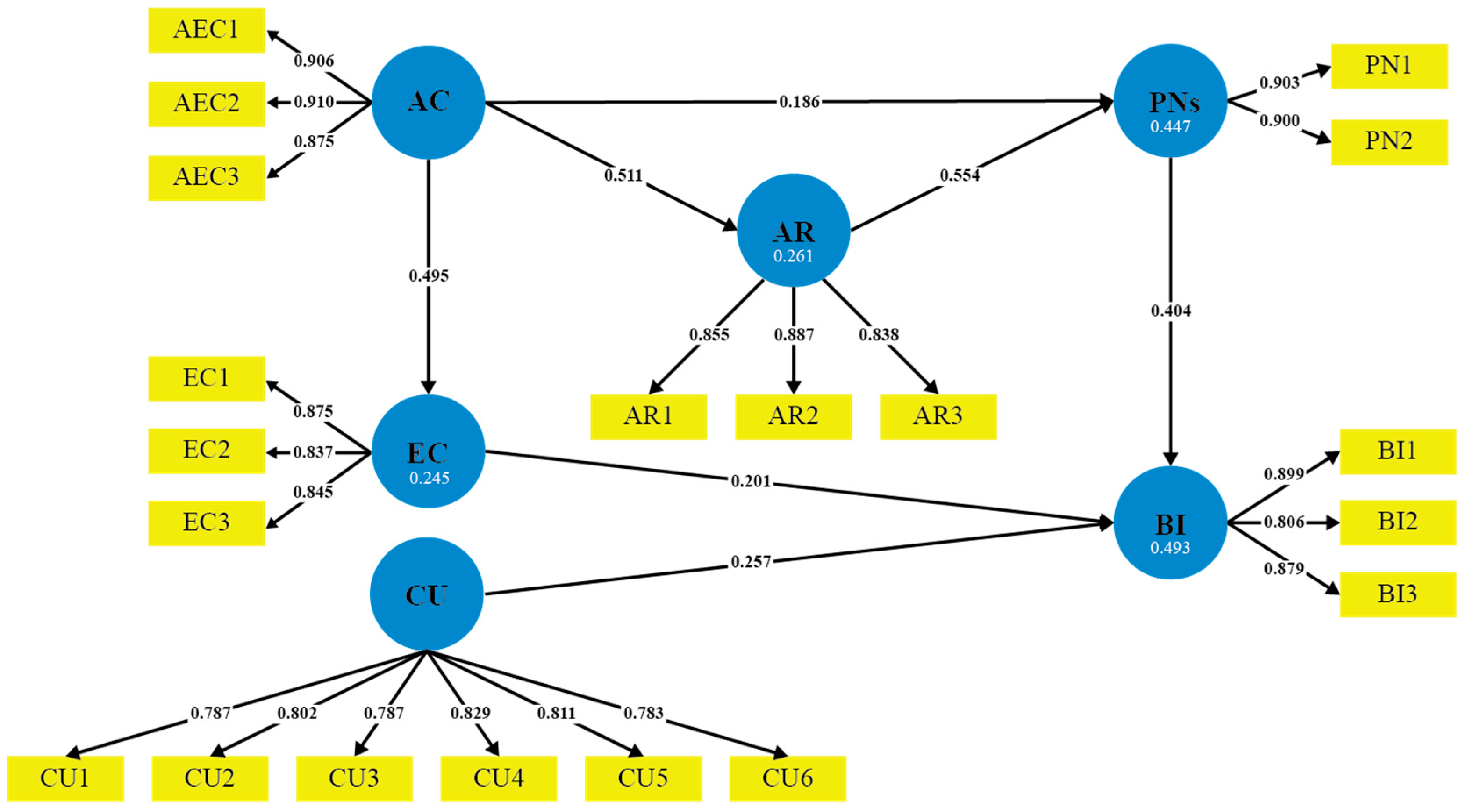

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis

4.2. The Kano Model Subjective Quality Attributes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hale, E. Taiwan Finds Diplomatic Sweet Spot in Bubble Tea. Al Jazeera. 2020. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/2020/6/26/taiwan-finds-diplomatic-sweet-spot-in-bubble-tea (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Hung, P.-Y. Food Nationalism beyond Tradition: Bubble Tea and the Politics of Cross-Border Mobility between Taiwan and Vietnam. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 50, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiges, J.; O’Neill, K. COVID-19 Has Resurrected Single-Use Plastics—Are They Back to Stay? The Conversation. 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/covid-19-has-resurrected-single-use-plastics-are-they-back-to-stay-140328 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Vanapalli, K.R.; Sharma, H.B.; Ranjan, V.P.; Samal, B.; Bhattacharya, J.; Dubey, B.K.; Goel, S. Challenges and Strategies for Effective Plastic Waste Management during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 750, 141514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Stadlthanner, K.A.; Andreu, L.; Font, X. Explaining the Willingness of Consumers to Bring Their Own Reusable Coffee Cups under the Condition of Monetary Incentives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, A.L.; Lorencatto, F.; Miodownik, M.; Michie, S. Influences on Single-Use and Reusable Cup Use: A Multidisciplinary Mixed-Methods Approach to Designing Interventions Reducing Plastic Waste. UCL Open Environ. 2021, 3, e025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoradovskaya, E.; Mullan, B.; Hasking, P. Choose to Reuse: Predictors of Using a Reusable Hot Drink Cup. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foteinis, S. How Small Daily Choices Play a Huge Role in Climate Change: The Disposable Paper Cup Environmental Bane. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziada, H. Disposable Coffee Cup Waste Reduction Study; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam, K.; Renganathan, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Muthunarayanan, V. Investigation on Paper Cup Waste Degradation by Bacterial Consortium and Eudrillus eugeinea through Vermicomposting. Waste Manag. 2018, 74, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H. Comprehensive Use of Recycling Cups Greenpeace Estimates That Taiwan will Reduce Carbon Emissions from 240,000 Motorcycles Per Year. Environmental Information Center. Available online: https://e-info.org.tw/node/237918 (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- GreenPeace. According to Green and Civilian Survey, Only 30% of Consumers Have Used Recyclable Cups. The Two Major Solutions Call on the Ministry of Environment to Continue Their Efforts. 15 August 2023. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/taiwan/press/37175/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Schutte, N.S.; Bhullar, N. Approaching Environmental Sustainability: Perceptions of Self-Efficacy and Changeability. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Tsetse, E.K.K.; Tulasi, E.E.; Muddey, D.K. Green Packaging, Environmental Awareness, Willingness to Pay and Consumers’ Purchase Decisions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A.; Zimmerman, J.; Erbug, C. Promoting sustainability through behavior change: A review. Des. Stud. 2015, 41, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boks, C. Design for sustainable behaviour research challenges. In Design for Innovative Value Towards a Sustainable Society, Proceedings of 7th International Symposium on Environmentally Conscious Design and Inverse Manufacturing, Kyoto, Japan, 30 November–2 December 2011; Mitsutaka, M., Yasushi, U., Keijiro, M., Schinichi, F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Prebežac, D. A critical review of techniques for classifying quality attributes in the Kano model. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Analysis of Factors Influencing Residents’ Habitual Energy-Saving Behaviour Based on NAM and TPB Models: Egoism or Altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopaei, H.R.; Nooripoor, M.; Karami, A.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C. Drivers of Residents’ Home Composting Intention: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Norm Activation Model, and the Moderating Role of Composting Knowledge. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shen, L.; Liu, W.; Wu, G. Uncovering People’s Mask-Saving Intentions and Behaviors in the Post-COVID-19 Period: Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding Consumer Recycling Behavior: Combining the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An Exploration of the Functions of Anticipated Pride and Guilt in Pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Zhang, Q.; Asmi, F.; Anwar, M.A.; Bhatia, M. Identifying the Motivating Factors to Promote Socially Responsible Consumption under Circular Economy: A Perspective from Norm Activation Theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cai, L.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X. Exploring Consumers’ Usage Intention of Reusable Express Packaging: An Extended Norm Activation Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I. Rational and Moral Antecedents of Tourists’ Intention to Use Reusable Alternatives to Single-Use Plastics. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. Intention and Behavior toward Bringing Your Own Shopping Bags in Vietnam: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Mark. 2022, 12, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Damaneh, H.E.; Cotton, M. Integrating the Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate Farmer Pro-Environmental Behavioural Intention. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the Norm Activation Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Context of Drone Food Delivery Services: Does the Level of Product Knowledge Really Matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Chiang, Y.-T.; Ng, E.; Lo, J.-C. Using the Norm Activation Model to Predict the Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Public Servants at the Central and Local Governments in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.F.; Kotchen, M.J.; Moore, M.R. Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.-W.; Wu, C.-C. Exploring Intention toward Using an Electric Scooter: Integrating the Technology Readiness and Acceptance into Norm Activation Model (TRA-NAM). Energies 2021, 14, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: Predicting energy behaviours with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behavior—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; de Groot, J. Explaining Prosocial Intentions: Testing Causal Relationships in the Norm Activation Model. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Lewis, A.N.; Dawkins, E.; Grah, R.; Vanhuyse, F.; Engström, E.; Lambe, F. Information as an Enabler of Sustainable Food Choices: A Behavioural Approach to Understanding Consumer Decision-Making. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshu, K.; Gaur, L.; Singh, G. Impact of Customer Experience on Attitude and Repurchase Intention in Online Grocery Retailing: A Moderation Mechanism of Value Co-Creation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Jun, M. Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Online Shopping Convenience. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Gifford, R.; Vlek, C. Factors Influencing Car Use for Commuting and the Intention to Reduce It: A Question of Self-Interest or Morality? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.G. Convenience in Services Marketing. J. Serv. Mark. 1990, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K.; Grewal, D. Understanding Service Convenience. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, P.N. Using Service Convenience to Reduce Perceived Cost. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer Switching Behavior in Service Industries: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zinkhan, G.M. Exploring the Impact of Online Privacy Disclosures on Consumer Trust. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; e Silva, S.C.; Ferreira, M.B. How Convenient Is It? Delivering Online Shopping Convenience to Enhance Customer Satisfaction and Encourage e-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-T.; Chang, K.-C.; Chen, M.-C.; Hsu, C.-L. Investigating the Effect of Service Quality on Customer Post-Purchasing Behaviors in the Hotel Sector: The Moderating Role of Service Convenience. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 13, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chen, M.; Hsu, C.; Kuo, N. The effect of service convenience on post-purchasing behaviours. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.E.; Chan, R.Y.; Yip, L.S.; Chan, A. Time Buying and Time Saving: Effects on Service Convenience and the Shopping Experience at the Mall. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer Reactions to Sustainable Packaging: The Interplay of Visual Appearance, Verbal Claim and Environmental Concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, N.; Gifford, R.; Milfont, T.L.; Weeks, A.; Arnocky, S. Learned Helplessness Moderates the Relationship between Environmental Concern and Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Waris, I.; Bhutto, M.Y.; Sun, H.; Hameed, I. Green Initiatives and Environmental Concern Foster Environmental Sustainability: A Study Based on the Use of Reusable Drink Cups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is Rapidly Accumulating Plastic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šuškevičė, V.; Kruopienė, J. Improvement of Packaging Circularity through the Application of Reusable Beverage Cup Reuse Models at Outdoor Festivals and Events. Sustainability 2021, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-H.; Lin, G.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, P.-Z.; Su, Z.-C. Exploring the Effect of Starbucks’ Green Marketing on Consumers’ Purchase Decisions from Consumers’ Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.; Steg, L. General Beliefs and the Theory of Planned Behavior: The Role of Environmental Concerns in the TPB. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1817–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qomariah, A.; Prabawani, B. The Effects of Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Concern, and Green Brand Image on Green Purchase Intention with Perceived Product Price and Quality as the Moderating Variable. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 448, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y. Consumers’ Intention to Bring a Reusable Bag for Shopping in China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information Publicity and Resident’s Waste Separation Behavior: An Empirical Study Based on the Norm Activation Model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to Activate Moral Norm to Adopt Electric Vehicles in China? An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Predict Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. An Assessment of Value Creation in Mobile Service Delivery and the Moderating Role of Time Consciousness. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekembayeva, G.; Garaus, M.; Schmidt, O. The Role of Time Convenience and (Anticipated) Emotions in AR Mobile Retailing Application Adoption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ren, C.; Dong, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Determinants Shaping Willingness towards On-Line Recycling Behaviour: An Empirical Study of Household E-Waste Recycling in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmaram, M.; Shiri, N.; Shinnar, R.S.; Savari, M. Environmental Support and Entrepreneurial Behavior among Iranian Farmers: The Mediating Roles of Social and Human Capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 1064–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K. Green University Initiatives and Undergraduates’ Reuse Intention for Environmental Sustainability: The Moderating Role of Environmental Values. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, J.K.-M.; Ho, J.M.; Hii, I.S. Green Meets Food Delivery Services: Consumers’ Intention to Reuse Food Delivery Containers in the Post-Pandemic Era. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.B.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahim, S.; Mir, B.A.; Suhara, H.; Mohamed, F.A.; Sato, M. Structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis of social media use and education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: An updated review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Jiao, R.J.; Yang, X.; Helander, M.; Khalid, H.M.; Opperud, A. An Analytical Kano Model for Customer Need Analysis. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S.-I. Attractive Quality and Must-Be Quality. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control. 1984, 14, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Aibinu, A.A.; Al-Lawati, A.M. Using PLS-SEM Technique to Model Construction Organizations’ Willingness to Participate in E-Bidding. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lai, P.-L.; Yang, C.-C.; Wang, X. Exploring the Factors That Drive Consumers to Use Contactless Delivery Services in the Context of the Continued COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Stevens Institute of Technology Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nofrizal; Juju, U.; Sucherly; Arizal, N.; Waldelmi, I.; Aznuriyandi. Changes and Determinants of Consumer Shopping Behavior in E-Commerce and Social Media Product Muslimah. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Kahneman, D. Duration Neglect in Retrospective Evaluations of Affective Episodes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Company | Gender | Title | Work Experience (y) | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDonald’s | F | Duty manager | 3 | 1 |

| McDonald’s | M | Duty manager | 2 | 2 |

| Starbucks | F | Duty manager | 5 | 3 |

| Starbucks | F | Employee | 3 | 4 |

| Starbucks | M | Employee | 2 | 5 |

| Bubble tea | F | Employee | 2 | 6 |

| Mentions Times | Factors |

|---|---|

| 4 | There are too few return points, which is inconvenient. |

| 3 | The overall return process is very inconvenient. |

| 3 | Returnable cups are easier to carry than to-go paper cups, so I would like to use them. |

| 3 | Customers find the service process troublesome. |

| 3 | Do not want to run back to the store just to return the cup for a special occasion. |

| 2 | Customers are worried about hygiene issues. |

| 2 | They do not want to use it because if they forget or do not have the time to return, the deposit will be deducted. |

| 1 | We can return the cups at 7–11, but not all of them. It depends on whether the store is a franchise or directly operated. Two stores also have membership requirements, so consumers feel it is complicated. |

| Category | Item | Factor | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of consequences (AC) | AC1 | Using returnable cups can improve the environment. | [26] |

| AC2 | Using returnable cups is environmentally friendly. | ||

| AC3 | Using returnable cups can reduce pollution. | ||

| Ascription of responsibility (AR) | AR1 | I feel partly responsible for the environmental problems caused by using single-use plastic (SUP) cups. | [26,64] |

| AR2 | I believe that consumers share some responsibility for the environmental problems associated with SUP cups. | ||

| AR3 | Because I do not use returnable cups, I feel jointly responsible for the environment’s pollution and ecological damage. | ||

| Personal norms (PNs) | PN1 | I feel it is my moral obligation to use returnable cups. | [26,63,65] |

| PN2 | Even if other people do not use returnable cups, I feel obligated to do so. | ||

| Environmental concern (EC) | EC1 | Environmental problems are of great importance to me. | [26,66] |

| EC2 | There is no way we can ignore the problems associated with the environment. | ||

| EC3 | It is important that we take care of the environment. | ||

| Convenience of use (CU) | CU1 | I think the current service model of returnable cups is convenient. | [61,62] |

| CU2 | I think location where you can rent returnable cups are quite common. | [63] | |

| CU3 | I think the portability of the returnable cup is convenient. | Interview | |

| CU4 | I think the return process of the returnable cup service is convenient. | ||

| CU5 | I thought it would be easy to take the rental returnable cups to a returning point. | [63] | |

| CU6 | There are many returnable cup collection sites near my home. | Interview | |

| Behavioral intention (BI) | BI1 | I will use the returnable cups. | [26,29] |

| BI2 | I like the idea of returnable cups | ||

| BI3 | I plan to use the service of returnable cups in the future. |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 293 | 51.3% |

| Female | 278 | 48.7% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 98 | 17.2% |

| 25–34 | 159 | 27.9% | |

| 35–45 | 175 | 30.6% | |

| More than 45 | 139 | 24.3% | |

| Education | High school or under | 148 | 25.9% |

| Bachelor’s | 346 | 60.6% | |

| Master’s or higher | 77 | 13.5% | |

| Experience of using returnable cups | Yes | 334 | 58.5% |

| No | 237 | 41.5% | |

| Frequency of drinking beverages (cups/week) | 1–3 times | 404 | 70.8% |

| 4–7 times | 119 | 20.8% | |

| More than 8 times | 48 | 8.4% |

| Factor | Item | Λ | VIF | AVE | CR (rho_a) | CR (rho_c) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of consequences (AC) | AC1 | 0.907 | 2.598 | 0.804 | 0.879 | 0.925 | 0.878 |

| AC2 | 0.907 | 2.686 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.875 | 2.129 | |||||

| Ascription of responsibility (AR) | AR1 | 0.855 | 1.924 | 0.739 | 0.826 | 0.895 | 0.824 |

| AR2 | 0.887 | 2.091 | |||||

| AR3 | 0.838 | 1.69 | |||||

| Personal norms (PNs) | PN1 | 0.903 | 1.637 | 0.812 | 0.768 | 0.896 | 0.768 |

| PN2 | 0.9 | 1.637 | |||||

| Convenience of use (CU) | CU1 | 0.791 | 1.736 | 0.64 | 0.905 | 0.924 | 0.889 |

| CU2 | 0.798 | 2.245 | |||||

| CU3 | 0.786 | 1.912 | |||||

| CU4 | 0.829 | 2.476 | |||||

| CU5 | 0.815 | 2.544 | |||||

| CU6 | 0.778 | 2.371 | |||||

| Environmental concern (EC) | EC1 | 0.872 | 1.993 | 0.727 | 0.812 | 0.889 | 0.812 |

| EC2 | 0.849 | 1.764 | |||||

| EC3 | 0.836 | 1.684 | |||||

| Behavioral intention (BI) | BI1 | 0.899 | 2.456 | 0.743 | 0.828 | 0.896 | 0.826 |

| BI2 | 0.806 | 1.534 | |||||

| BI3 | 0.879 | 2.303 |

| Direct Effects | β | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: AC → AR | 0.511 | 0.511 | 0.043 | 11.863 | 0 |

| H2: AR → PNs | 0.554 | 0.554 | 0.036 | 15.603 | 0 |

| H3: PNs → BI | 0.404 | 0.403 | 0.042 | 9.605 | 0 |

| H4: AC → PNs | 0.186 | 0.187 | 0.039 | 4.724 | 0 |

| H5: CU → BI | 0.257 | 0.259 | 0.037 | 6.957 | 0 |

| H6: AC → EC | 0.495 | 0.495 | 0.036 | 13.741 | 0 |

| H7: EC → BI | 0.201 | 0.201 | 0.041 | 4.894 | 0 |

| Indirect Effects | |||||

| AC → AR → PNs → BI | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.017 | 6.704 | 0 |

| AC → PNs → BI | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.018 | 4.079 | 0 |

| AC → EC → BI | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.021 | 4.654 | 0 |

| Experienced Consumer | Novice | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2 (+) | β2 Sig. | β1 (−) | β1 Sig. | Kano Category | β2 (+) | β2 Sig. | β1 (−) | β1 Sig. | Kano Category | |

| CU1 | 0.197 | * | −0.321 | * | O | 0.154 | * | −0.207 | * | O |

| CU2 | 0.127 | * | −0.118 | NS | A | 0.156 | * | −0.087 | NS | A |

| CU3 | 0.193 | * | −0.213 | * | O | 0.186 | * | −0.141 | * | O |

| CU4 | 0.200 | * | −0.210 | * | O | 0.198 | * | −0.051 | NS | A |

| CU5 | 0.127 | * | −0.196 | * | O | 0.263 | * | −0.020 | NS | A |

| CU6 | 0.159 | * | −0.065 | NS | A | 0.213 | * | −0.016 | NS | A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, D.J.; Chiu, T.-P.; Ma, M.-Y. How to Enhance Consumer’s Engagement with Returnable Cup Services? A Study of a Strategic Approach to Achieve Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114761

Yang DJ, Chiu T-P, Ma M-Y. How to Enhance Consumer’s Engagement with Returnable Cup Services? A Study of a Strategic Approach to Achieve Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114761

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Derrick Jessey, Tseng-Ping Chiu, and Min-Yuan Ma. 2024. "How to Enhance Consumer’s Engagement with Returnable Cup Services? A Study of a Strategic Approach to Achieve Environmental Sustainability" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114761