Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

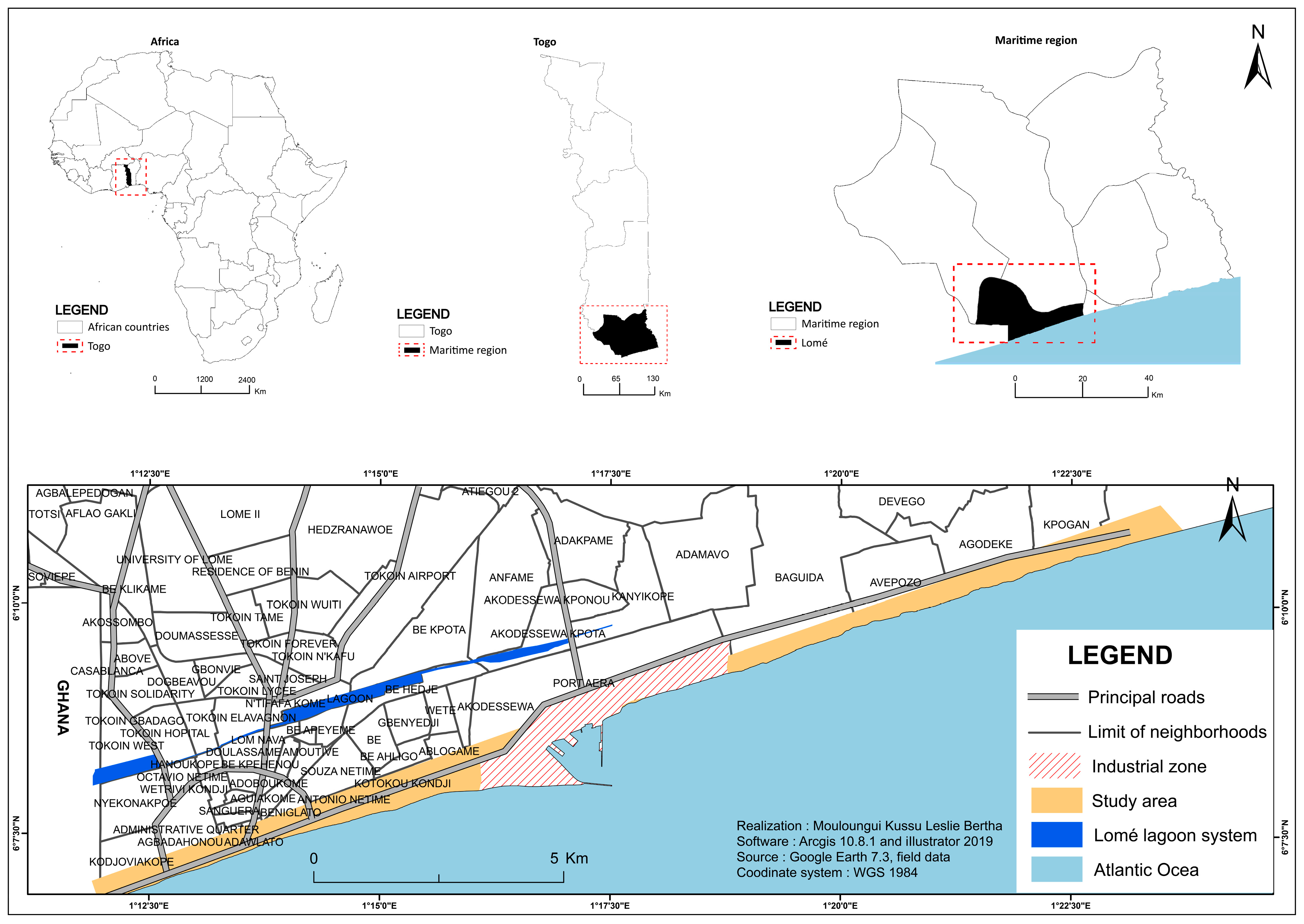

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

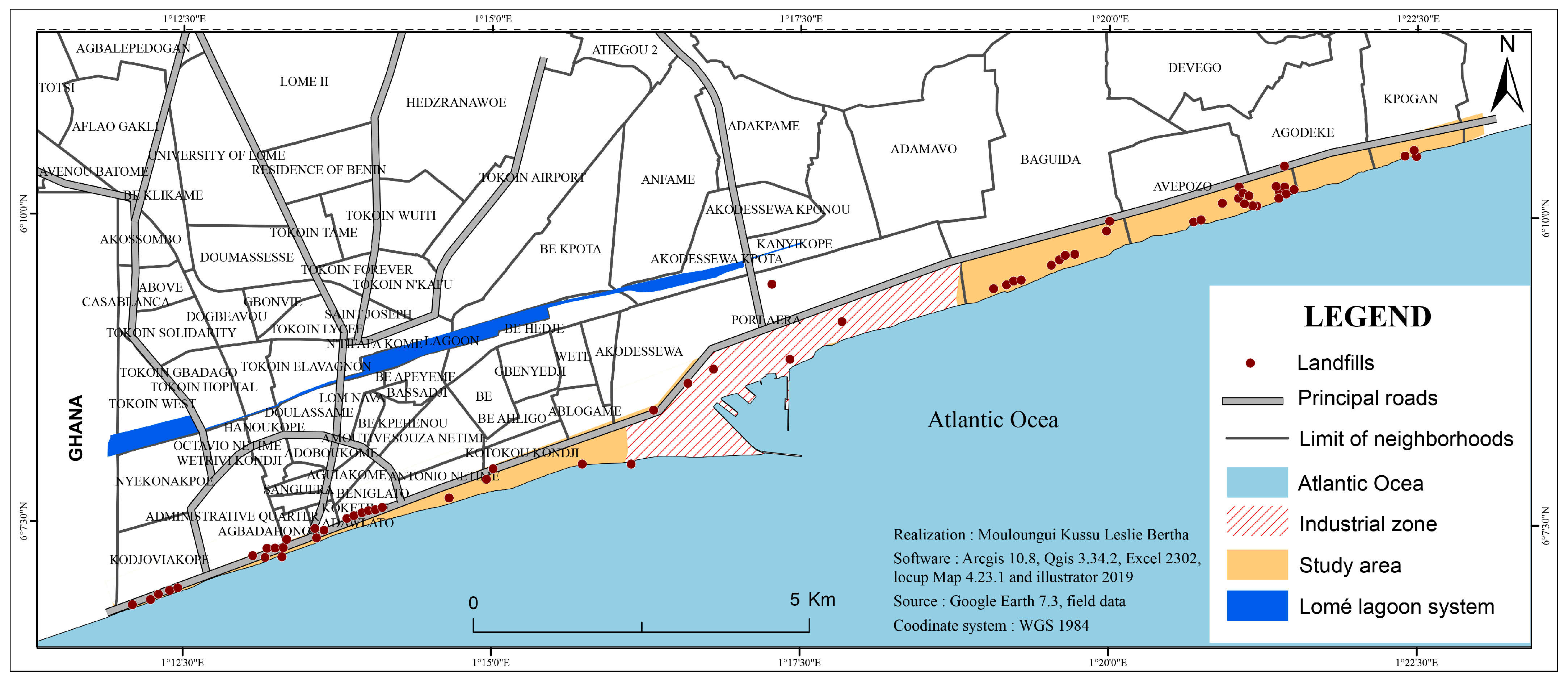

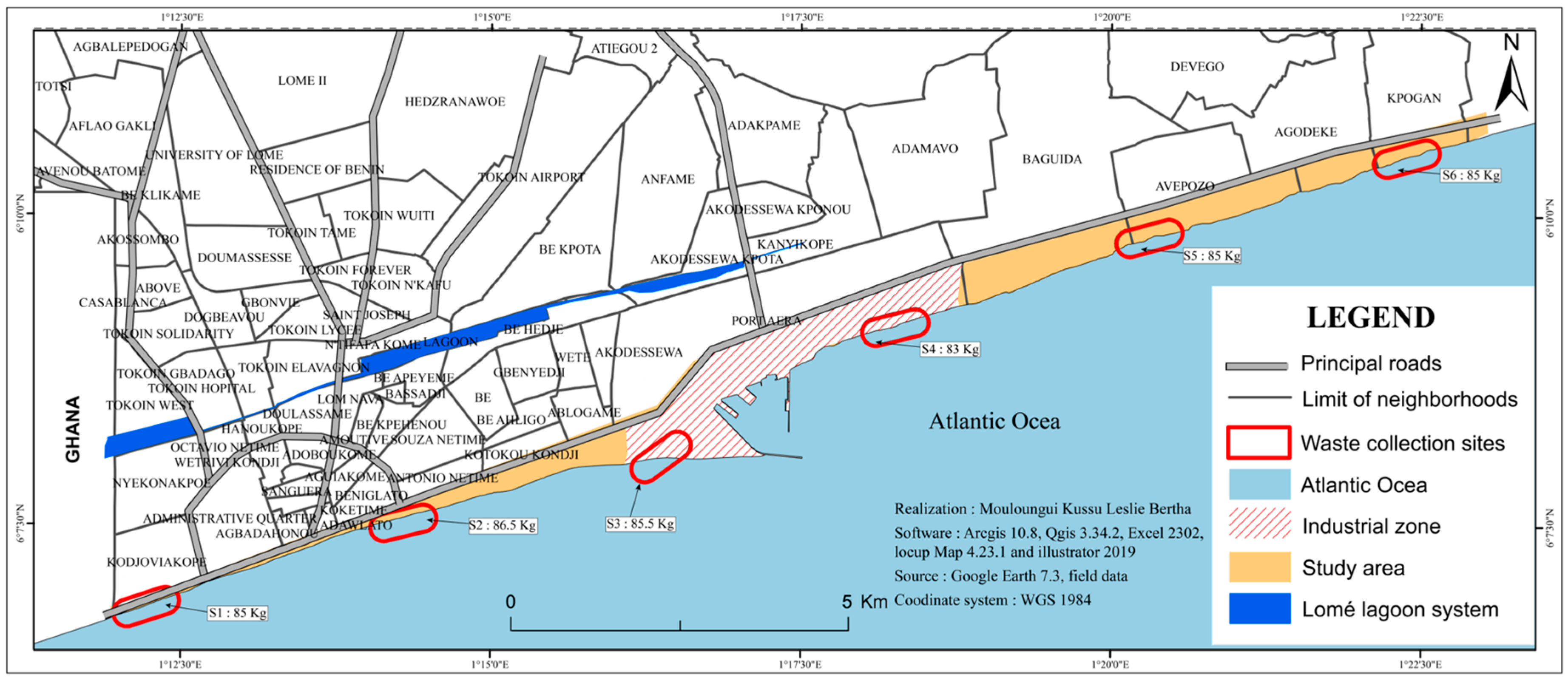

2.2.1. Mapping Waste Dumps along the Greater Lomé Coastline

2.2.2. Physical Characterisation of Solid Waste along the Greater Lomé Coastline

2.2.3. Surveys and Direct Observations in the Field

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Waste Deposits on the Aflao–Kpogan Coastal Strip

3.2. Physical Characterisation of Waste

- -

- Site 1 is dominated by green waste and wood (20.6%), followed by hard plastics (19.4%) and CNC (unclassified fuels) (14.5%), while the other categories are less than (10%);

- -

- Site 2 is dominated by paper and cardboard and flexible plastics, with more than (17%) each, followed by glass waste (16.9%) and CNC (unclassified fuels) (15.2%), while the other categories vary between 0 and 10%;

- -

- Site 3 is characterised by fine waste representing (23.4%) of the total, accompanied by soft plastic waste (19.7%), while the other categories vary between 0 and 10%;

- -

- Site 4 is dominated by green waste (19%), flexible plastics (18.4%) and fine waste (17.8%), while the other categories vary between 0 and 10% proportions;

- -

- Site 5 is characterised by flexible plastic waste (26.5%), followed by wood waste (22.4%) and fine waste (17.7%), while the other proportions range from 1 to 8%;

- -

- Site 6 is dominated by fine waste (38.2%), followed by flexible plastics (23.9%), while the proportions of the other categories vary between 0 and 8%.

| All Fractions | Site 1 % | Site 2 % | Site 3 % | Site 4 % | Site 5 % | Site 6 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green waste | 20.6 | 8.2 | 8 | 19 | 8.8 | 3 |

| Wood | 20.6 | 10.5 | 5.5 | 8.3 | 22.4 | 8.4 |

| Food | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 3 |

| Paper and cardboard | 0 | 17.6 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 3 |

| Soft plastics | 10.3 | 17.5 | 19.7 | 18.4 | 26.5 | 23.9 |

| Hard plastics | 19.4 | 5.3 | 8 | 10.1 | 6.5 | 7.8 |

| Simple textiles | 1.8 | 1.8 | 9.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| Sanitary textiles | 0 | 0.2 | 6.2 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Metals | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Glasses | 0 | 16.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| CNC (unclassified fuels) | 14.5 | 15.2 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| INC (non-combustible ungraded materials) | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 5. | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Special | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| Fine < 20 mm | 11.5 | 5.8 | 23.4 | 17.8 | 17.7 | 38.2 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

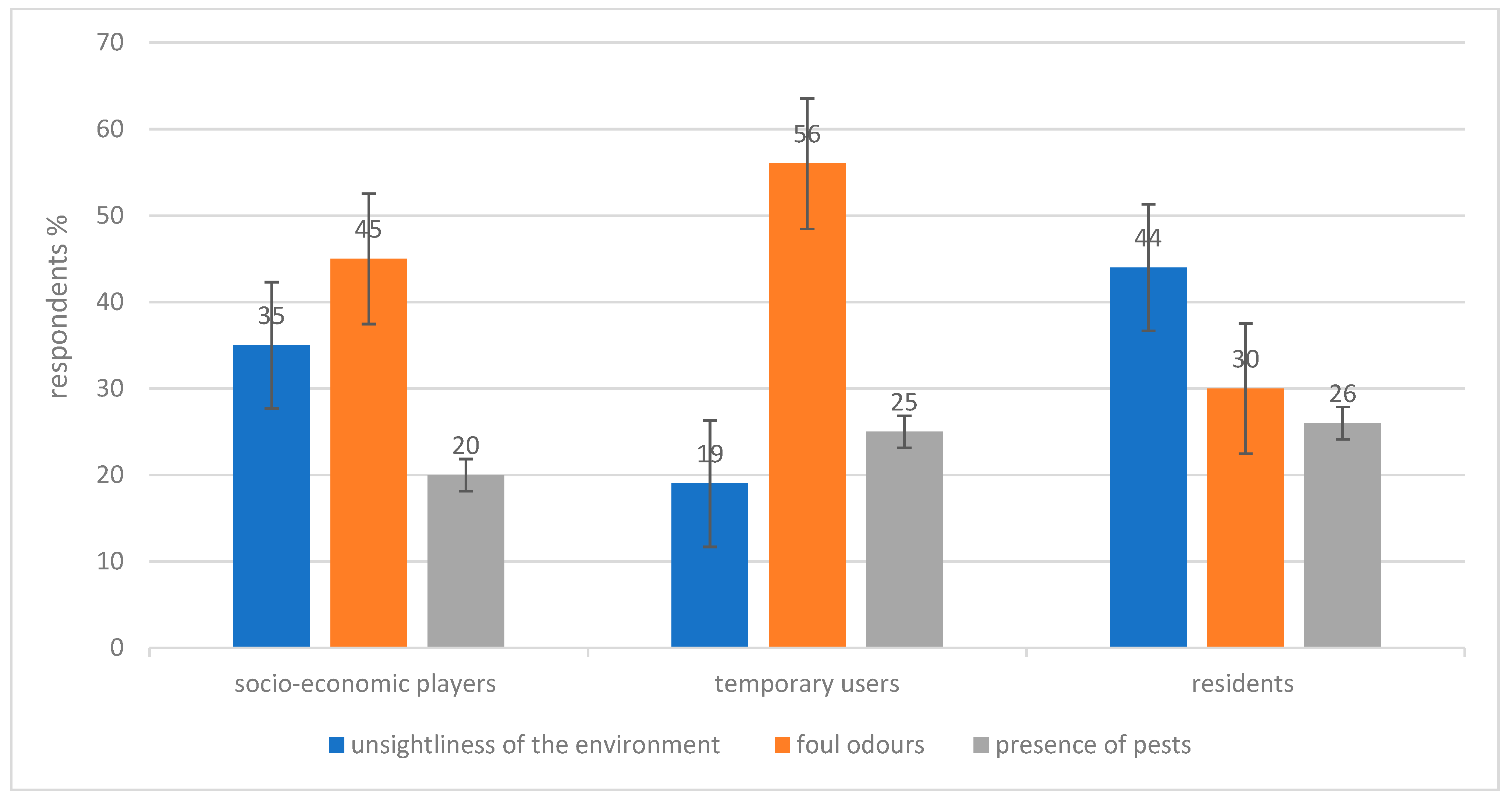

3.3. The Greater Lomé Coastline an Environment Threatened by Waste

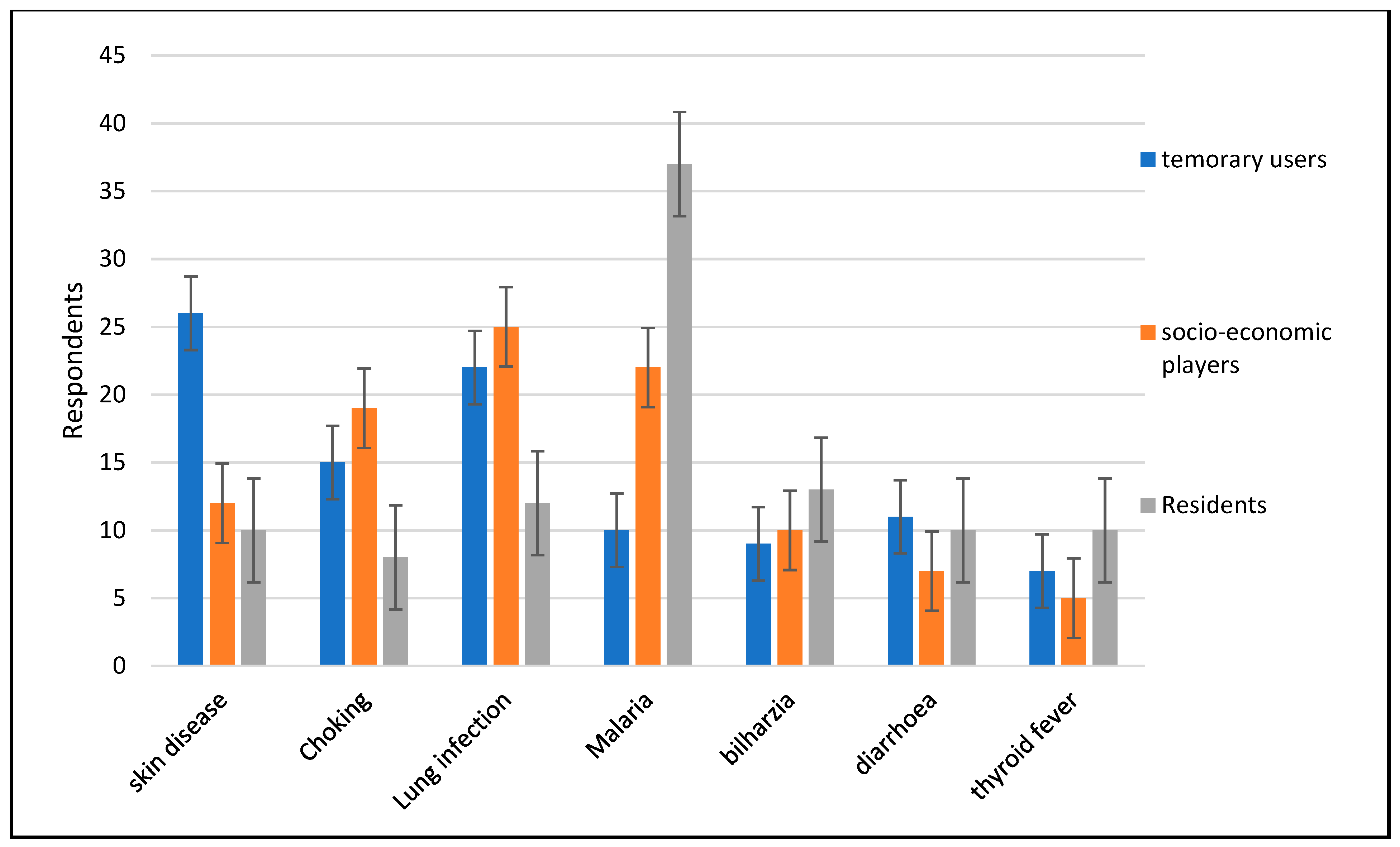

3.4. Health Risks to Local Populations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daniel, N. La population des littoraux du monde. Ingeo 1999, 63, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, R. Coastal Adaptation to Climate Change: Performative Governance through Experimentation and Public Action Strategies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, R. Coastal Urbanisation: Spaces, Landscapes and Representations. Territories at the City-Sea Interface. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale (UBO), Brest, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan, D. Analysis of Anthropogenic Pressures on the European and French Coastal Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of La Rochelle, Rochelle, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, B. Tourism development, urbanisation of the Mediterranean coastline and the environment. MEDIT W 1995, 2, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Conil, P.; Le Guern, C. Le littoral face aux pollutions. Geosciences 2013, 17, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kablan, N.H.J.; Pottier, P. Problématique de la Gestion Intégrée des Zones Côtières en Côte d‘Ivoire, Revue de Géographie du Littoral en Côte d‘Ivoire, in Anoh Paul and Patrick Pottier (dir) Géographie du Littoral Ivoirien 2008, 249–273. Available online: https://www.calameo.com/books/002797242bd3e9f6af01e (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Rogombe, L.G.; Lembe Bekale, A.J.; Mbadinga, M.; Mombo, J.B. Les facteurs anthropiques de la dégradation des mangroves d’Angondjé, Okala et Mikolongo au nord du Grand Libreville. ESJ 2022, 18, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandbois, M. La protection et la gestion des zones côtieres. Rev. Quebécoise Droit Int. 1998, 176–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiha, B.; Hamida, L. Contribution à l’Identification et à la Quantification des Déchets Solides Générés par les Estivants Dans la Plage de Corso (Wilaya de Boumerdès, Algérie) Approche Socio-Économique et Écologique. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Mouloud Mammeri, Tizi Ouzou, Algeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, N.; Emile, T. Les Villes d’Afrique Face à Leurs Déchets; Université de Technologie de Belfort-Montbéliard: Belfort, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- PNUE. Avenir de la Gestion des Déchets en Afrique; Programme des Nations Unies pour l’Environnement: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Étude de Collecte D’informations Relatives à la Gestion des Déchets Municipaux Solides dans les Villes d’Afrique; Rapport Final; JICA (Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale): Tokyo, Japan, 2022; p. 18.

- Tini, A. La Gestion des Déchets Solides Ménagers à Niamey au Niger: Essai Pour une Stratégie de Gestion Durable. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National de Lyon, Lyon, France, 2003. Available online: http://theses.insa-lyon.fr/publication/2003ISAL0084/these.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Edem, K.K. Valorisation des Déchets Solides Urbains Dans les Quartiers de Lomé (Togo): Approche Méthodologique Pour Une Production Durable de Compost. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lomé/Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Serge, O.A.L. Optimisation de la Gestion des Déchets Solides Ménagers en Milieu Urbain: Cas de la Ville de DAPAONG au Togo. 2015. Available online: https://docplayer.fr/74864208-Optimisation-de-la-gestion-des-dechets-solides-menagers-en-milieu-urbain-cas-de-la-ville-de-dapaong-au-togo.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Kpabou, Y.; Koledzi, K.E.; Baba, G.; Batawila, K.; Améyapoh, Y. Evaluation des Risques D’exposition à la Gestion des Déchets Solides Ménagers à Lomé. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2018, 149, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Planification du Développement et de la Coopération. 5ème Recensement General de la Population et de L’Habitat RGPH-5.p.2, Novembre 2022. Available online: https://www.togofirst.com/images/2023/RECENSEMENT_RESULTATS_.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Yacoubou, T. Insalubrite et Gestion des Dechets Menagers dans la Ville de Lome au TOGO. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lomé/Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aina, M.P. Expertises des Centres d’Enfouissement Techniques de Déchets Urbains dans les PED: Contributions à l’Élaboration d’un Guide Méthodologique et à sa Validation Expérimentale sur Sites. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lomé/Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh, E.; Bodjona, M.B.; Aziable, E.; Tchegueni, S.; Kili, K.A.; Tchangbedji, G. Etat des lieux de la gestion des déchets dans le Grand Lomé. Int. J. Bio. Chem. Sci 2019, 13, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messanh, K. Repenser la Gestion des Matières Résiduelles à Lomé au Togo; Université de Sherbrooke: Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ecole Africaine des Métiers de l’Architecture et de l’Urbanisme. Opportunités et Contraintes de la Gestion des Déchets à Lomé: Les Dépotoirs Intermédiaires; Rapport Final—September 2002 Projet de Recherche PSEAU/PDM/EAMAU; 2002; p. 53. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/epa/gdda/Actions/Action_D10/Annexes_rapport_final_D10.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Koledzi, K.E.; Baba, G.; Feuillade, G.; Guy, M. Caractérisation physique des déchets solides urbains à Lomé au Togo, dans la perspective du compostage décentralisé dans les quartiers. Environ. Ingénierie Dév. 2011, N°59, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFD. Vers Une Meilleure Gestion des Déchets à Lomé; AFD: Oberursel, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gnane, N.M. Gestion des déchets électroniques et enjeux environnementaux AU TOGO. Échanges 2017, 2, 484–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kofi, S.D. Etalement Urbain et Problematique de la Mobilite dans les Metropoles d’Afrique Subsaharienne: Etude de Cas du Grand-Lome au Togo; Université de Lome: Lomé, Togo, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agbemedi, Y.M. Production de la Plage dans le Grand Lomé (Togo) et le Greater Accra (Ghana): Pratiques, Logiques, Enjeux. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Journal Officiel De La Republique Togolaise. 2019, p. 2. Available online: https://jo.gouv.tg/sites/default/files/JO/JOS_19_11_2019-64E%20ANNEE%20N%C2%B0%2030BIS.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Vimenyo, M. Le Port Autonome de Lome et Son Arriere-Pays. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2006; p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de L’environnement et des Ressoureces Forestieres. Premier-rapport-sur-letat-de-lenvironnement-marinreem-du-TOGO_FV (1).pdf., p. 159. 2022. Available online: https://environnement.gouv.tg/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/PREMIER-RAPPORT-SUR-LETAT-DE-LENVIRONNEMENT-MARINREEM-DU-TOGO_FV.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Ministere de L’environnement et des Ressources Forestieres. Programme National de Suivi de L’environnement au Togo-PNSET.p.132. 2012. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/Tog183990.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Aloueimine, S.; Matejka, G.; Zurbrugg, C.; Sidi Mohamed, M. Caractérisation des déchets urbains de Nouakchott, partie 1: Conception d’une nouvelle méthodologie d’échantillonnage des déchets. Environ. Ingénierie Dév. 2006, N°44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essowè, K. Etude de l’etat des lieux de la Gestion et Caractérisations Physique et Chimique des Dechets Solides Menagers de la ville de Tsevie. Ph.D. Thesis, Universite De Lome, Lomé, Togo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiema, B.; Constantin, A. Dechets Plastiques a Ouagadougou: Caracterisation et Analyse de la Perception des Populations (BURKINA FASO). Institut International d’Ingénerie de l’Eau et de l’Environnement, p. 62. 2012. Available online: https://docplayer.fr/48820986-Dechets-plastiques-a-ouagadougou-caracterisation-et-analyse-de-la-perception-des-populations-burkina-faso.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Ngahane, E.L. Gestion Technique de l’Environnement d’Une Ville (BEMBEREKE au BENIN): Caractérisation et Quantification des Déchets Solides Émis; Connaissance des Ressources en Eau et Approche Technique. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yaméogo, J. Perceptions des Risques Environnementaux et Sanitaires liés à L’utilisation des Pesticides dans le Maraîchage Urbain à Koudougou (Burkina Faso): Approche par la méthode d’indice. Rev. Interdiscip. Resol-Trop. 2021, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cabane, F. Lexique D’écologie, D’environnement et D’aménagement du Littoral. Version 24 [Recto-Verso]; Ifremer: Brest, France, 2012; 342p. [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio, C.A. L’émergence et les perceptions des risques socio-environnementaux liés aux pratiques d’assainissement et aux usages de l’eau sur la lagune Aghien en Côte d’Ivoire. Afr. Sociol. Rev. Rev. Afr. Sociol. 2020, 24, 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bébé, K.; Assi, Y.G.; Jacques, L.K. Degradation du cadre de vie et risques sanitaires à bingerville (CÔTE D’IVOIRE). Rev. Espace Territ. Sociétés Et Santé 2021, 4, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Koné-Bodou, P.J.; Victor, K.K.; Charles, F.D.; Yapi, D.A.C.; Kouadio, A.S.; Sanogo, Z.B.E.T.A. Risques sanitaires liés aux déchets ménagers sur la population d’Anyama (Abidjan-Côte d’Ivoire).html. VertigO—Rev. Electron. Sci. L’Environ. 2019, 19, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Rabah, C.; Abbes, A.; Borhane Djebar, A. Déchets solides encombrants les plages d’Annaba. Synthèse Rev. Sci. Technol. 2008, 17, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pessièzoum, A. La plage de Lomé: L’exutoire insalubre des égouts de la ville, témoins de la dynamique côtière. Rev. Géogr. Trop. D’Environ. 2016, 153–164. Available online: https://www.revues-ufhb-ci.org/fichiers/FICHIR_ARTICLE_2165.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Aloueimine, S. Methodologie de Caracterisation des Dechets Menagers a Nouakchott (Mauritanie): Contribution a La Gestion des Dechets et Outils D’aide a la Decision; Université de Limoges: Limoges, France, 2006; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- Edem, K.; Sema, A.-I.M.; Aziable, E.; Sizing, B. Caractérisation des Déchets Plastiques et leur Valorisation dans le Béton au Togo. 2023, pp. 345–356. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368817673 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Tramoy, R.; Gasperi, J.; Tassin, B. Plastoc: Indicateurs de la Pollution en Macrodéchets dans L’environnement et Estimation des Flux Issus des Eaux Urbaines. Laboratoire Eau Environnement et Systèmes Urbains (LEESU), hal-04006271, p. 80. 2022. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04006271v1/document (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Wulandari, D.; Warmadewanthi; Pandebesie, E.S.; Cahyadi, M.N.; Anityasari, M.; Dwipayanti, N.M.U.; Purnama, I.G.H.; Addinsyah, A. Solid waste management in a coastal area (Study Case: Sukolilo Sub-district, Surabaya). Sustain. Resil. Coast. Manag. 2021, 799, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiansyah, H.; Saiya, H.G.; Afkarina, K.I.I.; Indra, T.L. Coastal Community Perspective, Waste Density, and Spatial Area toward Sustainable Waste Management (Case Study: Ambon Bay, Indonesia). Sustainability 2021, 13, 10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, W.; Birahayu, D.; Adhayanto, O.; Irman, I. Marine Coastal Waste Management in the Coastal Area of Gresik Regency as an Effort to Maintain the Potential of Marine Resources. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Social-Humanities in Maritime and Border Area, SHIMBA 2022, Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia, 18–20 September 2022; EAI: Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia, 2022; p. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, M.; Abdoli, M.; Mehrdadi, N.; Mousavinezhad, M. Municipal Solid Waste Management in Coastal line of Gilan Province. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2014, 2, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Hitige, L.; Samarakoon, T. Status of Solid Wastes and its Management in the Coastal Environments of Sri Lanka. IJEAB 2021, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitou, I.; Kerambrun, L. Pressions Physiques et Impacts Associés Autres Perturbations Physiques Dechets sur le Littoral; Ifremer: Brest, France, 2012; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaha, A. Macrodéchets Dans le Littoral d’Annaba: Bilan, Impact et Gestion Intégrée; Université Badji Mokhtar–Annaba Faculté Des Sciences Département Des Sciences De La Mer: Annaba, Algeria, 2018; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Gohourou, F.; Yao-Kouassi, Q.C.; Ahua, É.A. Activités Humaines et Dégradation des Eaux en Milieu Littoral: Cas de la Ville de San-Pédro (Sud-Ouest de la Cote D’Ivoire). 2019, pp. 327–341. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03186708/ (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Maryvonne, H. Pollution du Milieu Marin par les Déchets Solides: Etat des Connaissances Perspectives D’implication de L’Ifremer en Réponse au Défi de la Directive Cadre Stratégie Marine et du Grenelle de la Mer; Ifremer: Brest, France, 2010; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Bouba, D.F. Santé Environnementale dans les Villes en Afrique Subsaharienne: Problèmes Conceptuels et Méthodologiques. ESJ 2019, 15, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onibokun, A.G. La Gestion des Déchets Urbains.html, KARTHALA, et CRDI. 2001. ISBN 0-88936-927-5. Available online: https://idrc-crdi.ca/sites/default/files/openebooks/927-5/index.html (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Ibrahima, A.; Traore, S.S.; Mathias Dolo, A.D. Assainissement et Risques de Maladies dans la Commune vi du District de Bamako, Mali. ESJ 2023, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guylain, N.N.; Benjamin, K.T.; Aime, K.K. Impact of household waste on the environment and health in the periphery of Kinshasa, drc. Afr. Sci. J. 2023, 3, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Batch | GPS Position | Initial Mass Weighed Kg | Mass after Characterization Kg | Error Rate % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (Ghana–Togo border at Kodjoviakopé) | X:301,229.89 Y:676,121.95 | 85 k | 83.8 | −1.5 |

| S2 (Opposite the Asigame market in Lomé) | X:305,054.80 Y:677,365.35 | 86.5 | 85.7 | +0.8 |

| S3 (Ablogamé) | X:308,887.33 Y:678,347.11 | 85.5 | 81.1 | −2.3 |

| S4 (Katanga) | X:312,374.87 Y:680,269.33 | 83 | 84.3 | −1.5 |

| S5 (Baguida) | X:316,153.89 Y:681,595.76 | 85 | 84.8 | −2.0 |

| S6 (Kpogan) | X:319,982.18 Y:682,773.74 | 85 | 82.6 | −2.8 |

| Total | 510 | 502.3 | Average: −1.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mouloungui Kussu, L.B.; Zoo Eyindanga, R.C.; Vimenyo, M.; Ngawandji, B.N.; Fiagan, K.-A.; Mambani, J.-B. Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124968

Mouloungui Kussu LB, Zoo Eyindanga RC, Vimenyo M, Ngawandji BN, Fiagan K-A, Mambani J-B. Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo. Sustainability. 2024; 16(12):4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124968

Chicago/Turabian StyleMouloungui Kussu, Leslie Bertha, René Casimir Zoo Eyindanga, Messan Vimenyo, Brigitte Nicole Ngawandji, Koku-Azonko Fiagan, and Jean-Bernard Mambani. 2024. "Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo" Sustainability 16, no. 12: 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124968

APA StyleMouloungui Kussu, L. B., Zoo Eyindanga, R. C., Vimenyo, M., Ngawandji, B. N., Fiagan, K.-A., & Mambani, J.-B. (2024). Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo. Sustainability, 16(12), 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124968