Charting the Professional Development Journey of Irish Primary Teachers as They Engage in Lesson Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Professional Development (PD) in Ireland

- What are Irish primary teachers’ reactions to LS as a PD model?

- What are teachers’ beliefs regarding LS as a sustainable model of PD?

2. Lesson Study (LS) as a Form of Professional Development

2.1. Japanese Lesson Study

2.2. Lesson Study (LS) outside Japan

3. Research on Lesson Study (LS)

4. Impetus for This Study

- What are Irish primary teachers’ reactions to LS as a PD model?

- What are teachers’ beliefs regarding LS as a sustainable model of PD?

5. Methodology

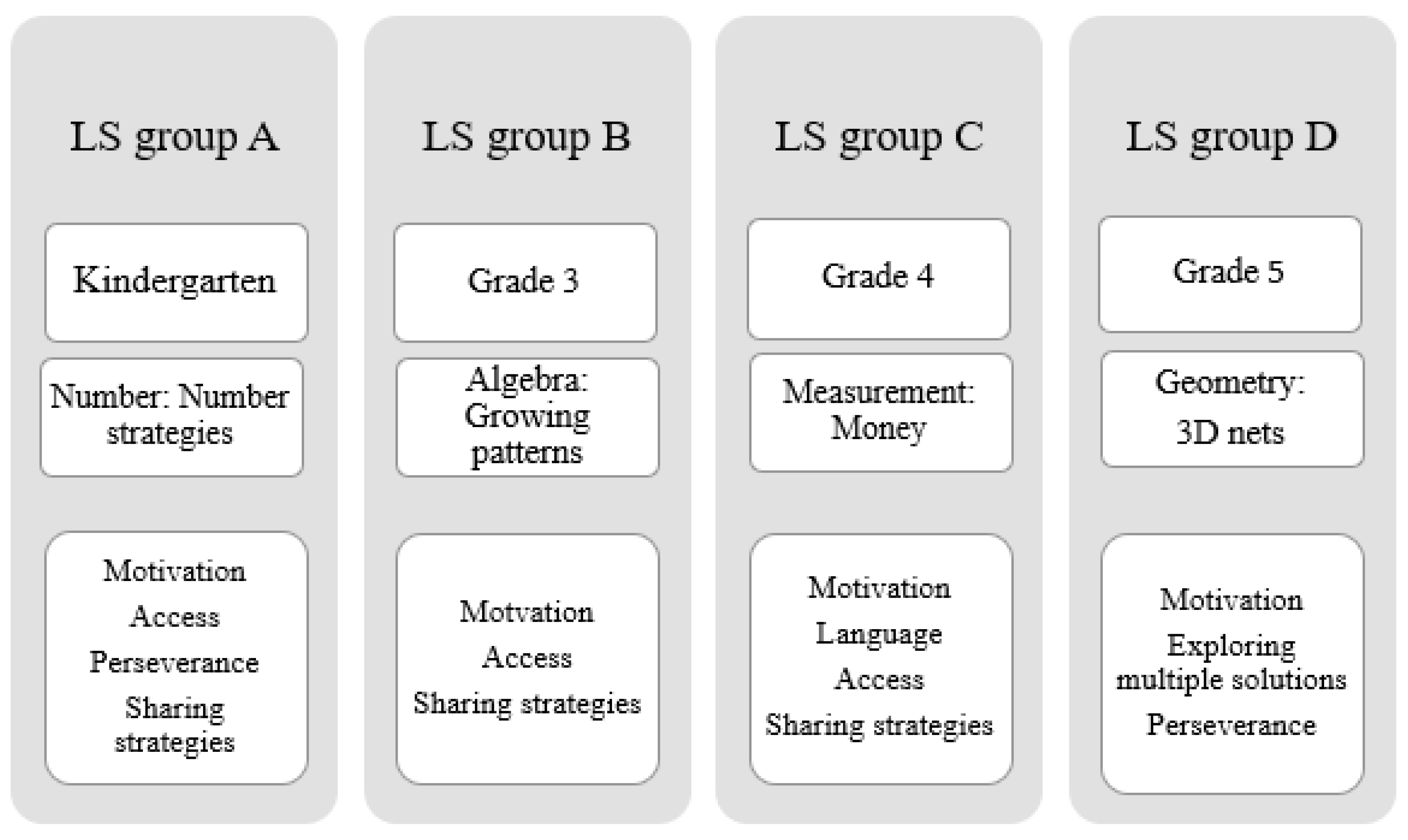

5.1. Context and Participants

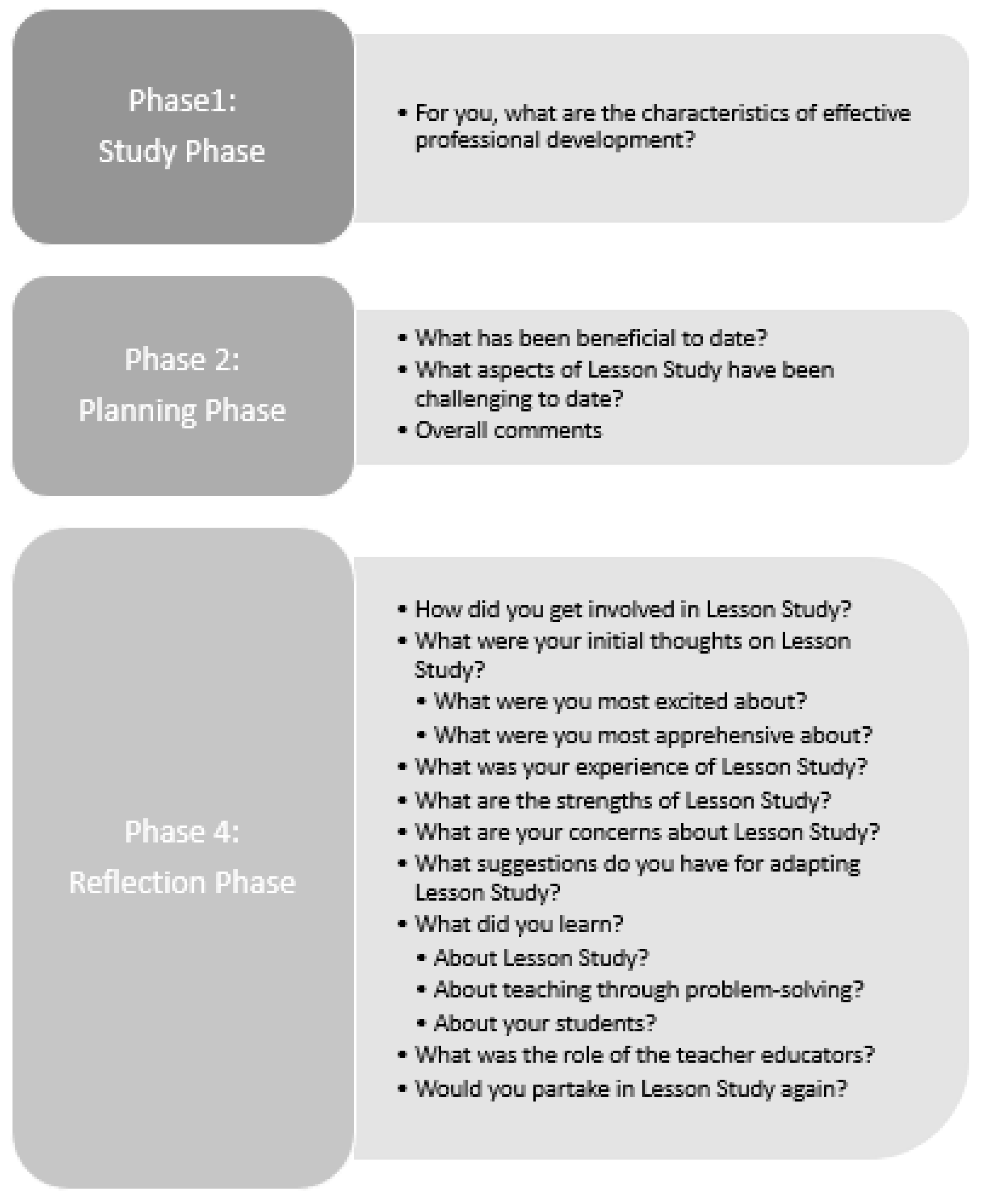

5.2. Data Collection

5.3. Data Analysis

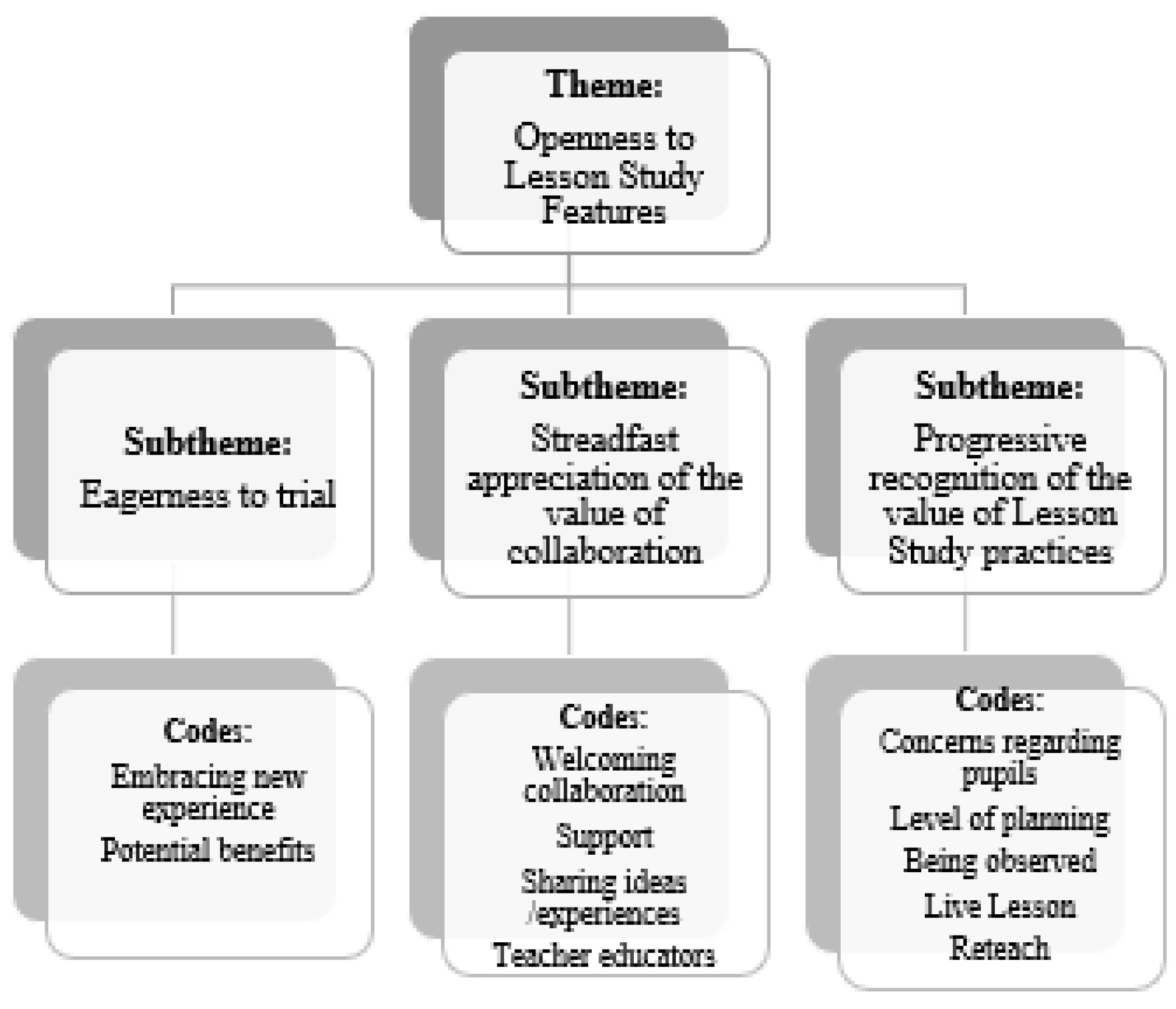

6. Findings

6.1. Openness to LS Features

6.1.1. Eagerness to Trial

I was approached by my principal…I was happy to take part but I didn’t really know anything about it(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I was curious to see how the process worked and what I would take from it. What were the underlying principles guiding Lesson Study(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Would any of the materials/strategies/methods influence my further teaching?(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I was most excited about doing something new with my kids as part of our maths LS group. It’s always good to allow for change(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Exciting to be part of! Eager to see how it will pan out and the learning that will be taken from it, to be used again in the future(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

As this is very new to us and something we haven’t engaged with before in our school we are relying on you both for expertise and instruction so that it will hugely benefit the school as a whole(Phase 1, email correspondence)

6.1.2. Steadfast Appreciation of the Value of Collaboration

I loved the idea of collaboratively planning and reflecting. The chance to see other teachers’ styles(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I was curious about working collaboratively with a teacher from other schools. Not something I’d have a lot of experience with(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I thought it was a very interesting concept. I liked the idea of collaborating with other schools and also the opportunity to work with senior maths lecturers, sharing knowledge and developing new skills(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Working in a group and the nice dynamic it creates(Phase 2, teacher reflection)

The interesting ideas I would never think of(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

The task when hashed with a few teachers appears less daunting(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

They kept the group focused and provided support and advice and quality feedback(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Collaboration with other teachers/facilitators—sharing ideas, planning together, thrashing out different ideas/methods/strategies(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Problem-solving is an area of great difficulty across the school…The pressure was alleviated working with another school(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I felt it was a very supportive process and we were all in it together. Listening to each other’s ideas and concern. All comments valued(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Good to get insight into where other schools are at, and the issues they face. Interesting to see we had similar goals and challenges(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

It’s a fantastic way to introduce/encourage collaboration in a school where this isn’t already happening(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

6.1.3. Progressive Recognition of the Value of LS Practices

It seemed like a lot of work for one lesson(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

What are the benefits of predicting the children’s responses?(Phase 1, fieldnotes)

Beneficial to tease out a relatively narrow topic over a protracted period, getting the chance to think(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

What I really liked about it was the focus and attention to detail(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Taking children’s different ways of thinking into consideration and being mindful of them going forward(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Collaborative planning, predicting strategies students may develop, reviewing the first teach, opportunity to reflect informed the reteach lesson(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Pressure on the teachers actually teaching the lessons(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Teaching in front of so many adults that I knew were more experienced than myself(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Apprehensive about teaching in front of academics(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Once it began, I realised it was a collaborative lesson that we all created together…(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

My biggest take away… seeing other teachers in action was really worthwhile and we can learn a lot from each other(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

It was tough having so many teachers and lecturers watching me. I’m glad it’s over but am happy enough with how it went(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

It puts pressure on the teaching teacher(Phase 4, teacher reflection)

The fear that the children will not understand the lesson objective. How will they respond?(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

…how the kids would react to more adults in the room? Was it a true lesson?(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Possibly a bit apprehensive about other schools having a different (higher) level(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

But it wasn’t a problem…the students didn’t bat an eyelid at the extra people in the room and responded well to the problem(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Having additional sets of eyes picking up on how the children tackle the task set will help as sometimes the teacher may not pick up on everything themselves(Phase 2, Fieldnotes)

Teachers’ observations of your class- watching/understanding children’s many ways of thinking/solving—seeing pupils through the process(Phase 4, teacher reflection)

[I] like the fact that we are evaluating the lesson and learning from both the positives and negatives(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Our trying it informed our practice(Phase 4, fieldnotes)

Focus- it’s rare we get a chance to re-evaluate teaching methods. Nice to be able to tweak after the first lesson(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

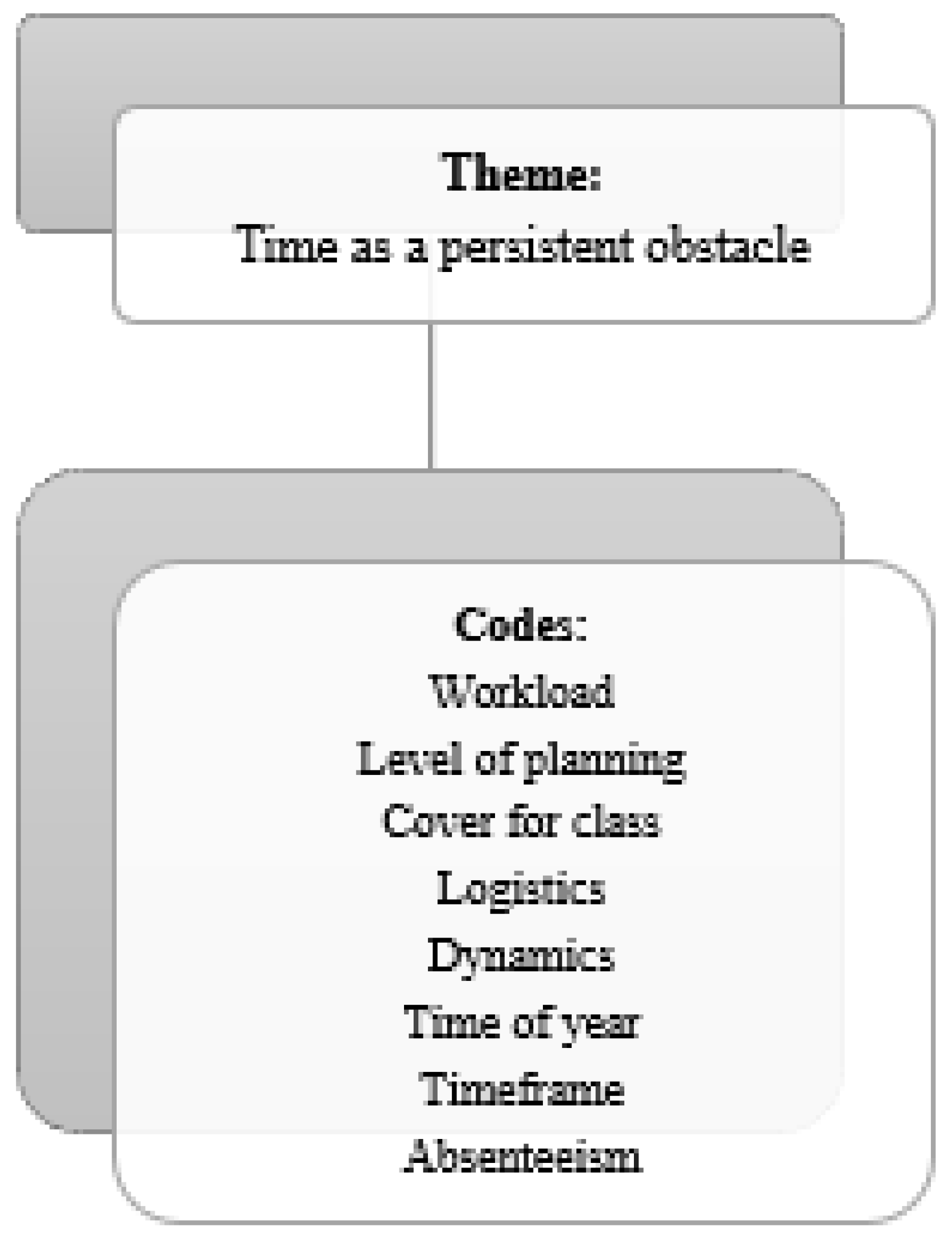

6.2. Time as a Persistent Obstacle

I was apprehensive about the workload involved, getting cover for my class, paper work overload and time investment(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Again, during the planning phase, all teachers mentioned time-related challenges: The amount of time you have to spend outside the classroom for the preparation. Preparation is excellent but just getting class cover can be difficult(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

There won’t be further opportunities for the teachers involved to collaborate before the next meeting(Phase 2, email correspondence)

We found it hard to meet as [teachers’ name] was [on leave] and I was on a course(Phase 2, fieldnotes)

… we spent the majority of the time trying to create a problem that would be accessible to the children yet challenging- we never got to the lesson plan…(Phase 2, fieldnotes)

We tried to populate the lesson template but it was new and very time consuming at the start(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Feeling overwhelmed by it…a lot of time has been put into it(Phase 2, fieldnotes)

We have an issue with the final meet [reflection phase]- it won’t work. We’d prefer not to rush one of the most beneficial parts. We’re just so busy- it’s the time of year(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

Timeframe very limited(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Researcher: Despite meetings scheduled since the start, only two of the four teachers are present(Phase 2, fieldnotes)

Unfortunately, we are unable to attend the sharing session. We are extremely busy that day in school and there are no teachers available to cover both our classes(Phase 3, email correspondence)

This meeting was quite frantic, with multiple parallel conversations happening at the same time and one teacher continuously revisiting previously discussed topics. Such narratives and stories tended not to progress the meeting but rather draw us away from the focus. Nonetheless, while it may not have been as linear as I wished, the group managed to make key decisions and discuss many pertinent and relevant areas(Phase 2: Researcher reflection)

It’s highly valuable but time consuming(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Lots of time constraints(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

6.3. Acknowledgement of Gains

6.3.1. Learning through LS

My main learning was that I under-estimated my kids which was awful(Phase 4, fieldnotes)

Children surprised me with the way they approached the problem given that the teacher gave them little information on how to solve the problem(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

We tend to spoon-feed them… We need to find a balance…We need to break the cycle…(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

Over-scaffolding, I use a lot of teacher talk, surprised with what they could do. I need to pull back(Phase 4, fieldnotes)

The problem is key, we don’t spend enough time picking the problem(Phase 4, fieldnotes)

Aim for problems with multiple strategies and solutions(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

It was an eye opener to me. If it’s relevant to them they will engage, persevere and share(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

LS allowed me to see the importance of children sharing ideas and how it helps/motivates others around them. Sharing and explore ‘more than 1 way’ is a vital part of teaching(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Let the children solve problems their own way and then communicate it back to their class. Maths dialogue is important(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

6.3.2. Commitment to LS Moving Forward

I’ll definitely do it again, it’s worth doing, very beneficial(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

Lesson Study is a daunting process but I found it very worthwhile. I would be very much delighted to take part again. It provides great collaboration to gain new knowledge and ideas(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Great opportunity for the children and teacher to learn(Phase 2, Teacher reflection)

Very transferable(Phase 4, Fieldnotes)

Gives you a chance to choose any area of the curriculum you may lack confidence in and get insights/ideas/help from other teachers(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

We hope to teach the lesson again in one of the other classes(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

I plan to try the other [LS groups’] lessons(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Yes, within our school to change our math teaching. Other teachers in the school have shown an interest to find out what LS involved. I would be keen to try LS out again. I hope to set up a group in the school(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

6.4. Tweaking LS to Strengthen the Fit

Class level appropriate, practical in application(Phase 1, Teacher reflection)

Ongoing support was also considered desirable: Continued contact(Phase 1, Teacher reflection)

I initially thought it wasn’t realistic but bringing it down to your own classroom it is relevant(Phase 4, fieldnotes)

We could pick a subject/area for the term/year and have each class level do a mini Lesson Study and share at Croke Park hours [additional non-contact hours](Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

…may only be feasible once or twice a year if you were hoping to get it up and running over a period of time(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

If lecturers could develop a presentation that we could show to the whole staff before LS so everyone is on board/understands the general idea(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

A whole school approach(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Principals should be more involved(Phase 4, Teacher reflection).

Time factor cannot be ignored. Unless the necessary time is given, it may become ‘just another initiative.’ Difficult to reconcile both parts of the issue(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Plan LS earlier in the term. Perhaps spring would be better in general(Phase 4, teacher reflection)

Online sessions might be helpful as there’s no teacher cover available(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

If skype (or something similar) could be used, it might be easier to liaise with the group(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

…in an already overcrowded curriculum I feel the planning element may not be as in-depth(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Would have loved more time together as a group to plan the lesson together(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

Maybe an extra meeting before the final teach(Phase 4, Teacher reflection)

There’s a lot of time and work involved in consulting with another school but I could see it work within our own school. There’s a culture in the school of staying back to work together after school and that it would be more manageable within our own school(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

I would like to be involved with another school as I feel this enhances the process, and also really allows you to focus on the lesson when they aren’t your children. Do it a few times a year…Liaise with other schools(Phase 3, fieldnotes)

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owens, D.C.; Sadler, T.D.; Murakami, C.D.; Tsai, C.-L. Teachers’ views on and preferences for meeting their professional development needs in STEM. Sch. Sci. Math. 2018, 118, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierez, S.B. Building a classroom-based professional learning community through lesson study: Insights from elementary school science teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2016, 42, 801–817. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt, J.D.; Vrikki, M.; van Halem, N.; Warwick, P.; Mercer, N. The impact of Lesson Study professional development on the quality of teacher learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 81, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, F.H. Teachers’ attitudes towards Lesson Study, perceived competence, and involvement in lesson study: Evidence from junior high school teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2020, 46, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park Rogers, M.; Abell, S.; Lannin, J.; Wang, C.Y.; Musikul, K.; Barker, D.; Dingman, S. Effective professional development in science and mathematics education: Teachers’ and facilitators’ views. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2007, 5, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewald, C.; Murwald-Scheifinger, E. Lesson study in teacher development: A paradigm shift from a culture of receiving to a culture of acting and reflecting. Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Nihill, M. The impact of policy on leadership practice in the Irish educational context; implications for research. Ir. Teach. J. 2019, 7, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Teaching Council. Policy on the Continuum of Teacher Education; Teaching Council: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. From isolation to individualism: Collegiality in the teacher identity narratives of experienced second-level teachers in the Irish context. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2020, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). Looking at Our School 2016: A Quality Framework for Primary Schools; DES: Dublin, Ireland, 2016.

- Flanagan, B. Teachers’ Understandings of Lesson Study as a Professional Development Tool in a Primary Multi- Grade School. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Typical practices of Lesson Study in East Asia. Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusanagi, K.N. Historical Development of Lesson Study in Japan. In Lesson Study as Pedagogic Transfer. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 69. [Google Scholar]

- Makinae, N. The Origin and Development of Lesson Study in Japan. In Theory and Practice of Lesson Study in Mathematics. Advances in Mathematics Education; Huang, R., Takahashi, A., da Ponte, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, J.; Hiebert, J. Lesson Study, improvement, and the importing of cultural routines. ZDM Math. Educ. 2016, 48, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Yoshida, M. Lesson Study: A Japanese Approach to Improving Mathematics Teaching and Learning; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, A. Introduction: Conceptual overview of Lesson Study. In Lesson Study Research and Practice in Mathematics: Learning Together; Hart, L., Alston, A., Murata, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, P.; Xu, H.; Vermunt, J.D.; Lang, J. Empirical evidence of the impact of lesson study on students’ achievement, teachers’ professional learning and on institutional and system evolution. Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; McDougal, T. Collaborative lesson research: Maximizing the impact of lesson study. ZDM Math. Educ. 2016, 48, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Cannon, J.; Chokshi, S. Japan lesson study collaboration reveals critical lenses for examining practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2003, 19, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Professional Development Service for Teachers (PDST). Lesson Study 2023. Available online: https://pdst.ie/primary/stem/lesson-study (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Hourigan, M.; Leavy, A.M. The complexities of assuming the ‘teacher of teachers’ role during Lesson Study. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, M.; Leavy, A.M. Elementary teachers’ experience of engaging with Teaching Through Problem Solving using Lesson Study. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2023, 35, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, M.; Leavy, A.M. Learning from Teaching: Pre-service elementary teachers’ perceived learning from engaging in ‘formal’ Lesson Study. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2019, 38, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, A.M.; Hourigan, M. Using Lesson Study to support knowledge development in initial teacher education: Insights from early number classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 57, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Shúilleabháin, A. Developing mathematics teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge in Lesson Study: Case study findings. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 2016, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, J. What is Lesson Study? Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 45, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajkler, W.; Wood, P.; Norton, J.; Pedder, D.; Xu, H. Teacher perspectives about lesson study in secondary school departments: A collaborative vehicle for professional learning and practice development. Res. Pap. Educ. 2015, 30, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richit, A.; Ponte, J.P. Teachers’ perspectives about lesson study. Acta Sci. 2017, 19, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, M.; Wilkinson, B. Adopting an international innovation for teacher professional development: State and district approaches to Lesson Study in Florida. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 67, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotger, S. Methodological understandings from elementary science lesson study facilitation and research. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2015, 26, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M. Learning to lead, leading to learn: How facilitators learn to lead lesson study. ZDM Math. Educ. 2016, 48, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Perry, R.; Hurd, J. Improving mathematics instruction through lesson study: A theoretical model and North American case. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 2009, 12, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Perry, R. Lesson Study to scale up research-based knowledge: A randomized, controlled trial of fractions learning. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2017, 48, 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, R.C.; Lewis, C.C.; Rhoads, C.; Lai, K.; Riddell, C.M. Impact of Lesson Study and fractions resources on instruction and student learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2023, 92, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, J.W.; Hiebert, J. The Teaching Gap: Best Ideas from the World’s Teachers for Improving Education in the Classroom; The Free Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ertle, B.; Chokshi, S.; Fernandez, C. Lesson Planning Tool 2001. Available online: https://sarahbsd.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lesson_planning_tool.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Suter, W.N. Introduction to Educational Research: A Critical Thinking Approach, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L. Teaching as community property. Change 1993, 25, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.; Lewis, C. What is successful adaptation of lesson study in the US? J. Educ. Chang. 2009, 10, 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, M.; Murata, A.; Howard, C.C.; Wilkinson, B. Lesson study design features for supporting collaborative teacher learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 77, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LS Group A | LS Group B | LS Group C | LS Group D |

|---|---|---|---|

| This year in the North Pole, Santa has told the elves that the number of baubles on each Christmas tree must match the number displayed on the star on the top of the tree. Can you help Santa work out all the ways the Christmas trees can be decorated? | There will be a new skyscraper in Limerick. The builder needs your help to work out how many windows he will need to order. As it is a very narrow building, for each storey, there is one window on each side of the building and a sunroof on the top. Instead of counting the number of windows each time, we want to help the builder to come up with a quicker way to work out the total number of windows required. | The principal teacher has received money for new equipment for the school and has selected your class to help decide what equipment should be purchased. The budget is €1000. You and your partner need to think carefully about what the school needs. You must buy at least one item from each of the 5 shops. You must not spend more than the budget. You will be reporting your ideas back to the principal. | A factory was printing nets for Christmas-themed gift boxes (cubes) in the lead up to Christmas. However, the printer malfunctioned and started to produce random nets. While some nets are correct, others are faulty and do not make a cube. Your help is needed to identify as many different correct nets for the cube. |

| Data Source | Phase 1 Study | Phase 2 Planning | Phase 3 Implementation | Phase 4 Reflection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fieldnotes | X | X | X | X |

| Email correspondence | X | X | X | X |

| Teacher reflection | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hourigan, M.; Leavy, A.M. Charting the Professional Development Journey of Irish Primary Teachers as They Engage in Lesson Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124997

Hourigan M, Leavy AM. Charting the Professional Development Journey of Irish Primary Teachers as They Engage in Lesson Study. Sustainability. 2024; 16(12):4997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124997

Chicago/Turabian StyleHourigan, Mairéad, and Aisling M. Leavy. 2024. "Charting the Professional Development Journey of Irish Primary Teachers as They Engage in Lesson Study" Sustainability 16, no. 12: 4997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124997