Home Sweet Home? The Mediating Role of Human Resource Management Practices in the Relationship between Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking in the Public Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Study Hypotheses

2.1. Leadership and Human Resource Management Practices

2.2. Human Resource Management Practices and Quality of Life in Teleworking

2.3. Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking

2.4. Leadership, Human Resource Management Practices, and Quality of Life in Teleworking

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Test of the General Model Composed of the Measurement Models

4.2. Testing Hypotheses and the Mediation Model

5. Discussion, Implications, Limitations, and Agenda

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Vrontis, D.; Alessio, I. Work from anywhere and employee psychological well-being: Moderating role of HR leadership support. Pers. Rev. 2022, 51, 1967–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, N.; Hauff, S.; Gubernator, P. The joint role of HRM and leadership for teleworker well-being: An analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Allan, B.; Clark, M.; Hertel, G.; Hirschi, A.; Kunze, F.; Shockley, K.; Shoss, M.; Sonnentag, S.; Zacher, H. Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2021, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulou, E.P.; Georgiadou, A. Leading through social distancing: The future of work, corporations and leadership from home. Gend. Work Organ 2021, 28, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.; Weber, E.; Büttgen, M.; Huber, A. Leadership matters in crisis-induced digital transformation: How to lead service employees effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglioretti, M.; Gragnano, A.; Margheritti, S.; Picco, E. Not All Telework is Valuable. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovic, M.; Gahan, P.; Olsen, J.; Gulyas, A.; Shallcross, D.; Mendoza, A. Exploring the adoption of virtual work: The role of virtual work self-efficacy and virtual work climate. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 33, 3492–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprinou, V.D.I.; Tasoulis, K.; Kravariti, F. The impact of servant leadership and perceived organisational and supervisor support on job burnout and work-life balance in the era of teleworking and COVID-19. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.A.F.; Barroco SM, S. Revolução tecnológica e smartphone: Considerações sobre a constituição do sujeito contemporâneo. Psicol. Estud. 2023, 28, e51648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firfiray, S.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Can family firms nurture socioemotional wealth in the aftermath of Covid-19? Implications for research and practice. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2021, 24, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demo, G.; Coura, K.V.; Fogaça, N.; Costa, A.C.; Scussel, F.; Montezano, L. How Are Leadership, Virtues, HRM Practices, and Citizenship Related in Organizations? Testing of Mediation Models in the Light of Positive Organizational Studies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Buch, R.; Glasø, L. Abusive retaliation of low performance in low-quality LMX relationships. J. Gen. Manag. 2020, 45, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarinho, K.P.B.; Paschoal, T.; Demo, G. Teletrabalho na atualidade: Quais são os impactos no desempenho profissional, bem-estar e contexto de trabalho? Rev. Serviço Público 2021, 72, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.J.; Oliveira, A.C.; Silva, L.P.; Mendonça, C.M.C. Teletrabalho e qualidade de vida: Estudo de caso do poder judiciário em um Estado do Norte do Brasil. Rev. Gestão Desenvolv. 2021, 18, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.M.P.G.; Quishida, A.; Foroni, P.G. A Leader’s Role in Strategic People Management: Reflections, Gaps and Opportunities. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2017, 21, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.C.; Demo, G.; Paschoal, T. Do human resources policies and practices produce resilient public servants? Evidence of the validity of a structural model and measurement models. Rev. Bras. Gestão Neg. 2019, 21, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, D. Work-life program participation and employee work attitudes: A quasi-experimental analysis using matching methods. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2020, 40, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Lepak, D.P. A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2498–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B.; Hirudayaraj, M.; Nair, P.K. Leadership challenges and behaviours in the information technology sector during COVID-19: A comparative study of leaders from India and the U.S. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Orhan, M.A. How it started, how it’s going: Why past research does not encompass pandemic-induced remote work realities and what leaders can do for more inclusive remote work practices. Psychol. Lead. Leadersh. 2023, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, A.S.; Reis Costa, S.R.; Ferraz, F.T.; Rampasso, I.S.; Resende, D.N. An analysis of teleworking management practices. Work J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2023, 74, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthonysamy, L. Continuance intention of IT professionals to telecommute post pandemic: A modified expectation confirmation model perspective. Knowl. Manag. E Learn. 2022, 14, 536–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishaj, V.; Neziraj, E. The Impact of Covid-19 On Human Resource It-Management. Qual. Access Success 2022, 23, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkiolakis, T.; Komodromos, M. Supporting Knowledge Workers’ Health and Well-Being in the Post-Lockdown Era. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoal, T.; Silva, P.M.; Demo, G.; Fogaça, N.; Ferreira, M.C. Qualidade de vida no teletrabalho, redesenho do trabalho e bem-estar no trabalho de professores de ensino público no Distrito Federal. Context. Rev. Contemp. Econ. Gestão 2022, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.; Guimarães, L.; La Falce, J. Vivências de servidores em um contexto de desflexibilização da jornada de trabalho. Rev. Eletrônica Ciênc. Adm. 2023, 22, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.; Trochmann, M.B.; Millesen, J.L. Putting the Humanity Back into Public Human Resources Management: A Narrative Inquiry Analysis of Public Service in the Time of COVID-19. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2024, 44, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira AA, R.; Lucena NN, N.; Damascena LC, L.; Albuquerque, R.L.; Silva LB, G. Impactos da Pandemia da Covid-19 na Qualidade de Vida no Trabalho dos Gestores do IFPB, campus João Pessoa, em Atividades Home Office. Rev. Ciênc. Adm. 2022, 28, e13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhokwe, H. Evaluating a desire to telework model: The role of perceived quality of life, workload, telework experience and organisational telework support. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coura, K.V.; Demo, G.; Scussel, F. Inspiring managers: The mediating role of organizational virtues in the relation between leadership and human resource management practices. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2022, 38, e38519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Vieira, R.; Puente-Palacios, K.E. O Impacto da Liderança nos Comportamentos de Aprendizagem das Equipes de Trabalho. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2023, 39, e39509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Row, International Relations: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, M.G.L.; Pereira, M.M.; Freitas CP, P.; Valentini, F. Mediation of the meaning of work on the relationship between leadership and performance, controlling the response bias. Estud. Psicol. 2023, 40, e200103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, R.; Grip, A.; Baudewijns, C. Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, S.C.; Blenckner, K.; Diehl, J.H.; Feilke, J.; Frei, C.; Grikscheit, S.; Hünsch, S.; Kohring, K.; Lay, J.; Lorenzen, G.; et al. Abrupt Implementation of Telework in the Public Sector During the COVID-19 Crisis. Z. Arb. Organ. Psychol. AO 2021, 65, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Burgi-Tian, J. Talent management challenges during COVID-19 and beyond: Performance management to the rescue. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2021, 24, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Jeon, S.H. Do Leadership Commitment and Performance-Oriented Culture Matter for Federal Teleworker Satisfaction with Telework Programs? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2020, 40, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Cho, Y.J.; Song, H.J. How do managerial, task, and individual factors influence flexible work arrangement participation and abandonment? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.B.; Lee, D.; Sohn, H. How to Increase Participation in Telework Programs in U.S. Federal Agencies: Examining the Effects of Being a Female Supervisor, Supportive Leadership, and Diversity Management. Public Pers. Manag. 2019, 48, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.J.; Grotto, A.R. Who can have it all and how? An empirical examination of gender and work–life considerations among senior executives. Gend. Manag. 2017, 32, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, M.A.; Glikson, E. On the hazards of the technology age: How using emojis affects perceptions of leaders. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 0, 2329488420971690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.; Gomez-Mejia, L.; Firfiray, S.; Berrone, P.; Villena, V.H. Leader beliefs and CSR for employees: The case of telework provision. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, M.C.; Marin, S. Exploring public sentiment on enforced remote work during COVID-19. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlstrom, T.R. Telecommuting and Leadership Style. Public Pers. Manag. 2013, 42, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.; Tummers, L.; Bekkers, V. The Benefits of Teleworking in the Public Sector: Reality or Rhetoric? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 570–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K.M.; Allen, T.D.; Dodd, H.; Waiwood, A.M. Remote workers communication during COVID-19: The role of quantity, quality, and supervisor expectation-setting. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1466–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toleikienė, R.; Rybnikova, I.; Juknevičienė, V. Whether and how does the Crisis-Induced Situation Change e-Leadership in the Public Sector? Evidence from Lithuanian Public Administration. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020, 16, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M.; Roman, A.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: Identifying the elements of e-leadership. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2019, 85, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci-Ferris, M.; Grabsch, D.K.; Bobo, A. Positives, Negatives, and Opportunities Arising in the Undergraduate Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2021, 62, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buengeler, C.; Leroy, H.; De Stobbeleir, K. How leaders shape the impact of HR’s diversity practices on employee inclusion. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Poutsma, E.; Van Der Heijden BI, J.M.; Bakker, A.B.; De Bruijn, T. Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatema, N. Stimulation of Efficient Employee Performance through Human Resource Management Practices: A Study on the Health Care Sector of Bangladesh. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. LAR Cent. Press 2018, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M. Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 13th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, A.O.; Kirschbaum, C. Fundamentos de gestão estratégica de pessoas. In Gestão Estratégica de Pessoas: Evolução, Teoria e Crítica; Cengage Learning: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, K. Human resource management. In The Oxford Handbook of Work and Organization; Ackroyd, S., Batt, R., Thompson, P., Tolbert, P., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, K. Human Resource Management: Rethorics and Realities; Macmillan: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demo, G.; Costa, A.C.; Coura, K.V.; Miyasaki, A.C.; Fogaça, N. What do scientific research say about the effectiveness of human resource management practice? Current itineraries and new possibilities. Rev. Adm. Unimep. 2020, 18, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bastida, R.; Marimon, F.; Carreras, L. Human resource management practices and employee job satisfaction in nonprofit organizations. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2018, 89, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demo, G.; Fogaça, N.; Costa, A.C. Políticas e práticas de gestão de pessoas nas organizações: Cenário da produção nacional de primeira linha e agenda de pesquisa. Cad. EBAPE BR 2018, 16, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, A.; Pangil, F. Mediating role of organizational commitment in the relationship between human resource management practices and employee engagement: Does black box stage exist? Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2018, 38, 606–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deadrick, D.L.; Stone, D.L. Human resource management: Past, present, and future. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 3, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.A.; Demo, G.; Caneppele, N.R. Com (ou sem) licença, estou chegando! (re)visitando itinerários de pesquisa e (re)desenhando práticas de gestão de pessoas para o teletrabalho. Rev. Eletrônica Ciênc. Adm. 2023, 22, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P. The strategic HRM debate and the resource-based view of the firm. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 1996, 6, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, V.; Dolamulla, S. The Effects of HRM Practices on Teamwork and Career Growth in Offshore Outsourcing Firms. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2017, 36, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among romanian employees—Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Cobo, M.J. What is the future of work? A science mapping analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.C.; Petsangsri, S.; Cui, Y. Positive Affect Predicts Turnover Intention Mediated by Online Work Engagement: A Perspective of R&D Professionals in the Information and Communication Technology Industry. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 764953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szulc, J.M.; McGregor, F.L.; Cakir, E. Neurodiversity and remote work in times of crisis: Lessons for HR. Pers. Rev. 2021, 52, 1677–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Pérez, M.P.; Jiménez MJ, V.; Carnicer, P.L. Telework adoption, change management, and firm performance. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2008, 21, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, E.; Kilaniotis, C. Flexible work and turnover: An empirical investigation across cultures. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Pérez, M.P.; Carnicer, P.L.; Jiménez MJ, V. Teleworking and workplace flexibility: A study of impact on firm performance. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathini, D.R.; Kandathil, G.M. An orchestrated negotiated exchange: Trading home-based telework for intensified work. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.M.; Țuclea, C.E.; Vrânceanu, D.M.; Țigu, G. Sustainable social and individual implications of telework: A new insight into the romanian labor market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). WHOQOL and Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs (SRPB); Report on WHO Consultation; MNH/MAS/ MHP/98.2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Klein, L.L.; Pereira BA, D.; Lemos, R.B. Qualidade de vida no trabalho: Parâmetros e avaliação no serviço público. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2019, 20, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.I.; Rueda, F.J.M. Effects of Organizational Values on Quality of Work Life. Paidéia 2017, 27, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, R.E. Quality of Working Life: What is it? Sloan Manag. Rev. 1973, 15, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeister, R.; Limongi-França, A.C. A Qualidade de Vida no Trabalho: Relações com o comprometimento organizacional nas equipes multicontratuais. Rev. Psicol. Organ. Trab. 2012, 3, 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Ferreira, R.R. Abordagem Teórico-Metodológica de Qualidade de Vida no Trabalho (QVT) de Suporte ao Projeto. In Qualidade de Vida no Trabalho (QVT) no Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq): Diagnóstico, Política e Programa; Paralelo: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LS, S.; Pantoja, M.P.; Figueira, T.G. Escala de Qualidade de Vida no Teletrabalho: Percepções de servidores e gestores públicos brasileiros. In Proceedings of the ANPAD Meeting (EnANPAD), Online Event, 14–16 October 2020; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sell, M.; Jacobs, S.M. Telecommuting and quality of life: A review of the literature and a model for research. Telemat. Inform. 1994, 11, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, S. New technologies and old ways of working in the home of the self-employed teleworker. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2002, 17, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissé, M.; Vonthron, A.M.; Vayre, É. Nomadic, Informal and Mediatised Work Practices: Role of Professional Social Approval and Effects on Quality of Life at Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.A.; Wallace, L.M.; Spurgeon, P.C. An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Empl. Relat. 2013, 35, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, S. Supplemental work at home among finnish wage earners: Involuntary overtime or taking the advantage of flexibility? Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2011, 1, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulate-Araya, R. Teletrabajo y su impacto en la productividad empresarial y la satisfacción laboral de los colaboradores: Tendencias recientes. Tecnol. Marcha 2020, 33, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, É.; Morin-Messabel, C.; Cros, F.; Maillot, A.S.; Odin, N. Benefits and Risks of Teleworking from Home: The Teleworkers’ Point of View. Information 2022, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demo, G. Políticas e Práticas de Gestão de Pessoas: Possibilidades de diagnóstico para gestão organizacional. In Análise e Diagnóstico Organizacional: Teoria e Prática; Mendonça, H., Ferreira, M.C., Neiva, E.R., Eds.; Vetor: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; pp. 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Raghuram, S.; Fang, D. Telecommuting and the role of supervisory power in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morilla-Luchena, A.; Muñoz-Moreno, R.; Chaves-Montero, A.; Vázquez-Aguado, O. Telework and social services in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, T.J.; Wang, Y. Forced shift to teleworking: How abusive supervision promotes counterproductive work behavior when employees experience COVID-19 corporate social responsibility. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2024, 37, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.C.B.; Roque, M.A.B. Atenção, memória e percepção: Uma análise conceitual da neuropsicologia aplicada à publicidade e sua influência no comportamento do consumidor. Intercom Rev. Bras. Ciências Comun. 2017, 40, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Hampshire, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Plataforma Nilo Peçanha. Indicadores da Gestão, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/pnp (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Brasil. Ministério da Gestão e da Inovação em Serviços Públicos. Confira Abaixo as Instituições com PGD em Execução, Assim Como os Seus Respectivos Normativos, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/servidor/pt-br/assuntos/programa-de-gestao/quem-ja-implementou (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. In Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, L.; Faiad, C.; Coelho Júnior, F.A. Análise psicométrica da escala de heteroavaliação de estilos de liderança. Estud. Psicol. 2016, 21, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demo, G.; Costa, A.C.; Coura, K.V. HRM Practices in the public service: A measurement model. RAUSP Manag. J. 2024, 59, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors and organizational effectiveness: Do challenge-oriented behaviors really have an impact on the organization’s bottom line? Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Descobrindo a Estatística Usando o SPSS, 5th ed.; Penso: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações, 3rd ed.; ReportNumber: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Zait, A.; Ioana, H. How Reliable are Measurement Scales? External Factors with Indirect Influence on Reliability Estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurombe, M.; Rayners, S.; Mokgobu, K.; Manka, K. The perceived influence of remote working on specific human resource management outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentjens, S.; Cherbib, J. Trust me if you can—Do trust propensities in granting working-from-home arrangements change during times of exogenous shocks? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 161, 113844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Shaikh, S.; Mirza, M.Z.; Obaid, A.; Muenjohn, N.; Ting, H. Work-From-Home in the New Normal: A Phenomenological Inquiry into Employees Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.; Mourão, L.; Cardoso VH, S.; Abbad, G.; Sandall, H.; Legentil, J.; Santos JO, P.L.; Carmo, E.A. Trabalhar de casa na pandemia: Sentimentos e vivências de gestores e não-gestores públicos. Estud. Psicol. 2023, 27, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago Torner, C. Teleworking and emotional exhaustion in the Colombian electricity sector: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of creativity. Intang. Cap. 2023, 19, 207–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Factors | Number of Items | Reliability Index * |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLS Scale | Focus on People (FP) | 07 | 0.90 1 |

| Focus on Results (FR) | 04 | 0.82 1 | |

| Public HRMPS | Relationship (REL) | 08 | 0.90 1/0.90 2 |

| Training, Development, and Education (TD & E) | 03 | 0.81 1/0.81 2 | |

| Performance and Skills Assessment (PSA) | 03 | 0.77 1/0.76 2 | |

| QoLT Scale | Work Self-Management (WSM) | 11 | 0.83 1 |

| Context of Teleworking (CT) | 06 | 0.79 1 | |

| Work Infrastructure (WI) | 03 | 0.79 1 | |

| Technological Structure (TS) | 03 | 0.88 1 | |

| Work Overload (WO) | 04 | 0.73 1 |

| Parameters | Reference Literature | General Model Result |

|---|---|---|

| NC (χ2/DF) | ≥2 and ≤3.0 | 2.54 |

| CFI | ≥0.9 | 0.97 |

| GFI | ≥0.9 | 0.96 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.08 |

| SRMR | ≤0.08 | 0.04 |

| Dimension | Factor | Charge Standardized | Standard Error | Critical Reason | Cargo Quality | R2 | Composite Reliability (Jöreskog’s Rho) | Extracted Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | FR | 0.814 ** | - | - | Excellent | - | 0.86 | 0.75 |

| FP | 0.917 ** | 0.102 | 11,835 | Excellent | ||||

| HRM Practices | TDE | 0.717 ** | - | - | Excellent | 47.4% | 0.81 | 0.60 |

| REL | 0.884 ** | 0.099 | 11,209 | Excellent | ||||

| PSA | 0.703 ** | 0.099 | 9850 | Excellent | ||||

| QoLT | WSM | 0.769 ** | - | - | Excellent | 9% | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| TS | 0.780 ** | 0.093 | 11,305 | Excellent | ||||

| WI | 0.849 ** | 0.113 | 11,635 | Excellent |

| Factor | L | HRM Practices | QoLT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | 0.75 a | ||

| HRM Practices | 0.47 | 0.60 a | |

| QoLT | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.64 a |

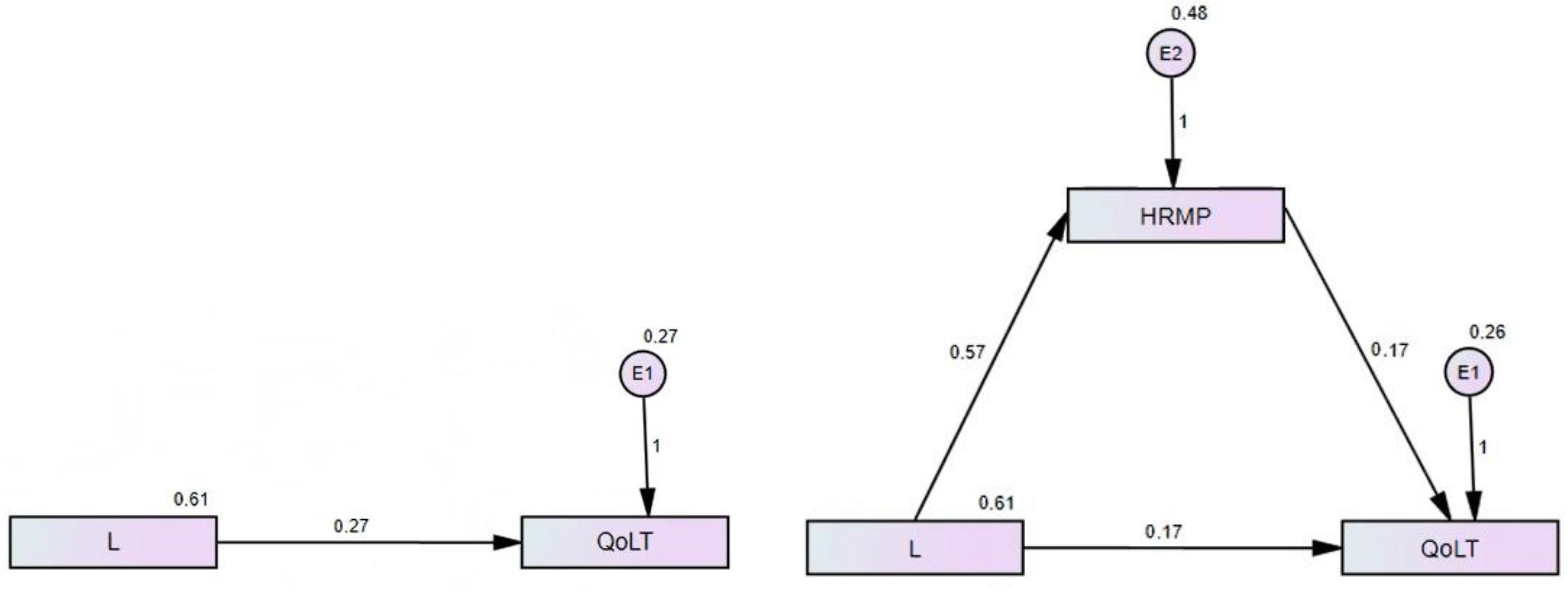

| Hypotheses | Relations | β |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Leadership → HRM Practices | 0.542 *** |

| H2 | HRM Practices → QoLT | 0.248 *** |

| H3 | Leadership → QoLT | 0.239 *** |

| Effect | Standardized Estimation | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.27 | 0.003 | Significant Impact |

| Direct | 0.17 | 0.003 | Significant Impact |

| Indirect | 0.10 | 0.009 | Significant Impact |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melo, T.A.d.; Demo, G. Home Sweet Home? The Mediating Role of Human Resource Management Practices in the Relationship between Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking in the Public Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125006

Melo TAd, Demo G. Home Sweet Home? The Mediating Role of Human Resource Management Practices in the Relationship between Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking in the Public Sector. Sustainability. 2024; 16(12):5006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelo, Tatiane Alves de, and Gisela Demo. 2024. "Home Sweet Home? The Mediating Role of Human Resource Management Practices in the Relationship between Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking in the Public Sector" Sustainability 16, no. 12: 5006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125006

APA StyleMelo, T. A. d., & Demo, G. (2024). Home Sweet Home? The Mediating Role of Human Resource Management Practices in the Relationship between Leadership and Quality of Life in Teleworking in the Public Sector. Sustainability, 16(12), 5006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125006