Abstract

Since 2018, the government of South Korea has strengthened its environmental policies to solve the problem of fine particulate matter in the air. Because of these strict regulations, diesel cars have been replaced with cleaner vehicles, and coal power plants have been shut down. Despite these government efforts, some researchers assert that fine dust programs have failed in Seoul, the capital of Korea. In other words, they conclude that the central and local governments designed and implemented the policies unreasonably. Despite these critics, this study attempts to prove that the government has thoroughly and meticulously prepared its policies on fine particles. Also, it tries to demonstrate that the policy scheme has been properly established. To attain these research goals, the theory of procedural rationality is adopted and utilized. As a result of the analysis, six steps of procedural rationality were identified in the Korean policy on fine dust: problem identification, goal setting, searching for alternatives, consequence prediction, comparison of alternatives, and policy decision. In conclusion, this study provides suggestions for environmental policies in other metropolitan cities, especially in developing countries that suffer from severe air pollution.

1. Introduction: A New Environmental Challenge of Fine Dust

South Korea has achieved rapid economic growth since the 1970s. As a side effect of material prosperity, it has experienced environmental pollution in advance of other developing countries such as Brazil, India, and China. However, the Korean government has dealt with its environmental problems effectively. These ecological outcomes could be explained by the hypothesis of the Environmental Kuznets Curve, which shows the relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation [1]. In brief, developing countries can improve their environmental quality after passing a specific turning point of economic income. Generally, the turning point of the per capita annual income is estimated at approximately USD 10,000 according to Grossman and Krueger (1995). In fact, the air and water quality of South Korea has improved since the 1990s [2]. Specifically, Jiang et al. (2020) identified an inverted U-shaped pattern with regard to air pollution in South Korea [3]. Likewise, Choi et al. (2015) showed that there was a significant improvement in the country’s water quality, and proved that economic growth accompanied a shift in environmental policy [4].

In spite of these positive outcomes, Koreans have a serious concern about the air pollution issue, especially about fine particulate matter. Kwag et al. (2021) reported that fine particulate matter became severe from 2010 to 2016 [5]. Therefore, emission control policies regarding fine dust have been introduced and executed to solve the air pollution problem [6]. Nevertheless, the government was alarmed that the level of ultra-fine dust exceeded environmental standards several times in 2018. Consequently, Koreans had to wear face masks to prevent inhaling fine particles. To make things worse, this issue provoked an international conflict, because the considerable amount of ultra-fine dust is regarded to have originated from China and moved to South Korea.

In addition, the problem of fine particulate matter has developed into a domestic political agenda in South Korea. For instance, Moon Jae-in, who was inaugurated as president in 2017, suggested aggressive policies to reduce the concentration level of ultra-fine dust as a presidential election pledge. As explained above, even though South Korea had shown positive performances in some environmental areas, it was still experiencing serious air quality degradation, especially with regard to fine particles [7].

In this context, where the policy of fine dust has become a critical issue at home and overseas, it is necessary for scholars to provide scientific research results because policies, fundamentally, are outcomes of political science. However, there have only been political controversies regarding fine dust issues in the Seoul Metropolitan Area, South Korea. Therefore, this study attempts to scientifically analyze the environmental policies on fine particulate matter from the viewpoint of procedural rationality. To attain these research goals, this study consists of five sections. In the following Section 2, the Korean policies on fine dust are described in outline. The basic theory of procedural rationality is illustrated in Section 3. Then, Section 4 analyzes the policy process of fine particles in the Seoul Metropolitan Area. In conclusion, Section 5 summarizes research results and suggests policy implications.

2. Literature Review of Korean Policies on Particulate Matter

2.1. Fine Dust Policies in South Korea

Air pollution has been a major field of environmental policies in South Korea, like in other industrialized countries. For instance, London smog is a well-known historical case of atmospheric pollution, induced by coal combustion in the 1950s, and Los Angeles also suffered from similar air pollution caused by vehicular emissions until the 1990s. Likewise, the Korean government has strengthened the standard of air quality and made strict policies since the 2000s [8].

In 2003, the central government of South Korea enacted the Special Act on the Improvement of Air Quality in Seoul Metropolitan Area and commenced enforcement of this Act in 2005. This was established because the capital city had faced a new kind of air pollution, fine particulate matter, unlike traditional pollutants such as sulfur oxides and nitrogen dioxide. Since then, fine dust has become a serious problem in this country. Based on this act, the First Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Control Master Plan was established in 2005. The major implementation measures are illustrated in Table 1. From then on, South Korea was able to formulate a systematic policy scheme to solve the problem of fine dust [9].

Table 1.

Implementation measures of the first master plan for metropolitan air quality management.

Hereafter, the Korean government endeavored to reduce the concentration of fine dust (particulate matter, PM). For instance, the concentration of PM10, a relatively large fine dust of which the diameter is around 10 μm, was 69 µg/m3 at that time, and the government set the ambitious goal of reducing this to 40 µg/m3, which was the same target level of the neighboring capital city, Tokyo in Japan. However, these policies were just focused on PM10. In other words, the Korean policy had limitations as it did not consider PM2.5, an ultra-fine dust of which the diameter is about 2.5 μm [11].

After ten years of the first master plan, the government presented the second master plan in 2013. This plan emphasized human health risks from air pollution and introduced a standard for PM2.5. In addition, the central government adopted new policy measures such as environmentally friendly power generation, industrial complexes with low emissions, the expansion of infrastructure for mass transportation, and so forth. Table 2 illustrates these new policy measures. Municipalities such as Seoul and Incheon followed the policy direction and cooperated with the central government [12].

Table 2.

Comprehensive measures for fine dust management in Korea.

In 2019, the administration of Jae-in Moon launched the National Council on Climate and Air Quality (NCCA), a new official control tower for fine dust. Ban Ki-moon, the former UN Secretary-General, was appointed as the chairperson of the NCCA to induce international cooperation with neighboring countries, including China. The most prominent feature of this council is the attendance of all the stakeholders such as experts, government officials, politicians, civic groups, and even ordinary citizens. In 2020, the council proposed a stern regulation of “No diesel vehicle sales by 2035”.

2.2. Results of the Policies

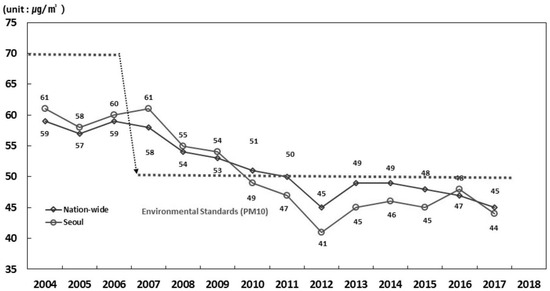

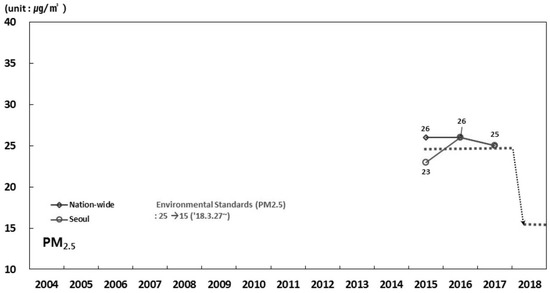

Owing to these aggressive responses, the air quality was improved nationwide and locally. In detail, the standard had been strengthened in 2006, and the goal of PM10 was achieved in 2011. Figure 1 shows the time-series changes in the PM10 concentration. Namely, national and local air quality was improved below the standard after the implementation of related policies for five years. However, ultra-fine dust pollution did not improve regardless of the new policies added in the second master plan. In other words, there had been no distinguished accomplishment, as seen in Figure 2. However, the Ministry of Environment decided to reinforce the standard of PM2.5 from 25 µg/m3 to 15 µg/m3 in 2015, although the performance was not satisfactory. From then on, ordinary citizens began to notice that they were living in bad air conditions and started to buy air purifiers and face masks. Consequently, air pollution has become a tangible concern since then [8].

Figure 1.

Concentration level of PM10 in South Korea. Source: [8].

Figure 2.

Concentration level of PM2.5 in South Korea. Source: [8].

In this situation, Kim and Lee (2019) diagnosed the effectiveness of fine dust policies and concluded that the programs of local governments did not work properly [13]. For example, while Seoul introduced free-riding programs for mass transportation in case of air pollution emergencies, these policies did not show the desired outcomes. Moreover, Choi and Kim (2016) insisted that it was inevitable for these programs to fail because of path dependency, which is a branch of irrational decision-making theory [14]. In other words, they concluded that the Korean policy on fine particles had been locked in the existing path of institutions and policies despite government efforts.

On the contrary, this study attempts to prove that the ultra-fine dust policy of Korea was relatively rational and reasonably well designed. However, in order to attain these research goals, it is necessary to narrow down the research topic. Therefore, the policy on fine dust equivalent to PM10 will be excluded, and it will focus on PM2.5 only. This is because the ultra-fine dust policy is more important in the viewpoint of its timeliness and seriousness. In fact, PM2.5 is related to lung cancers and the WHO has regarded it as a carcinogen since 2013. With this clarified and confined range of the research target, this study will analyze the process of the environmental policy on ultra-fine dust by adopting a Procedural Rationality Model. The following section, Section 3, will elaborate on basic theories about this rational model. In addition, the distinguishing features of this rational model in comparison to irrational models will be illustrated.

3. Methodology and Analysis Framework of Procedural Rationality

3.1. Irrational Decision-Making Theories

Policy-making procedures can be explained from two different viewpoints: the rational and the irrational models. First, some scholars insist that policy processes are irrational because policies are just the results of politics. Actually, public policies are designed, introduced, and developed by politicians. In this decision-making procedure, the power strength of advocacy groups determines their preferred policy. Consequently, policies are obliged to be irrational as the procedures are influenced by political powers [15].

One of the most famous irrational models for interpreting policy processes is the Garbage Can Model. This model was coined by Cohen, March, and Olsen in 1972 [16]. After analyzing decision-making procedures in the United States, they suggested the new concept of organized anarchy. Particularly, in some specific organizations such as parliaments and universities, these irrational traits were easily identified.

Concretely, they conceptualized this model as a garbage can that was full of agendas, problems, and issues with regard to public policy. In actuality, representatives in national parliaments tend to accumulate and delay bills submitted by ruling and opposition parties. However, these bills are finally passed within a package deal at some point, without a reasonable explanation. Like this, political decision-making is not rational, and policy is regarded as a product of a power game in this model.

In detail, the Garbage Can Model consists of social problems, participants, choice opportunities, and solutions for decision-making. Namely, these components are factors of organized anarchy. Additionally, Cohen et al. (1972) suggested three preconditions for applying the Garbage Can Model: problematic preference, unclear causality, and arbitrary participation [15]. To summarize, participants are not responsible for their attendance, the preference of decision-makers is disordered, and the causal relationship between policy goals and means is ambiguous in this irrational model.

Afterward, the Policy Stream Model was developed from the Garbage Can Model by John Kingdon in 1984. Because of this theoretical background, the Policy Stream Model is inevitably another irrational model for explaining policy processes from the viewpoint of politics. However, this model provides a more elaborate framework for policy analysis. Specifically, Kingdon (1984) illustrated that policy issues attain official agenda status, and solutions are chosen by decision-makers in the public sphere [17]. Currently, this model is also called the policy streams framework, the multiple streams model, or the multiple streams approach [18,19,20].

This model assumes that there are three independent streams in the policy process: a problem stream, a policy stream, and a political stream [21]. First, the problem stream contains the conditions and components of a specific issue. At a particular moment, these conditions come to the attention of decision-makers [22]. Second, the policy stream is related to alternative solutions to the problem. Kingdon described that solution ideas float around in a primeval policy soup [23]. Third, the political stream encompasses national moods, public opinion, and power dynamics. This stream naturally influences the receptiveness of voters to certain solutions [24].

In this Policy Stream Model, the meaningful point is the concept of policy windows, which is improved from the original Garbage Can Model. In short, as the three streams align by chance, policy windows are open for the establishment of new policies. Therefore, policy windows provide for the possibility of policy changes [19]. However, the periods of window opening are so short that policy entrepreneurs should actively attempt to introduce their preferred policies [25].

Until now, a number of scholars have shown an interest in this attractive model and utilized it to analyze social phenomena. Since 1984, hundreds of studies have cited Kingdon’s article and applied the Policy Stream Model in their analyses. Rawat and Morris (2016) illustrate this trend, reporting a peak in citations of Kingdon’s article during the mid-1990s and a downturn afterward. In this descending period, some researchers identified limitations in the Policy Stream Model [26]. For instance, defects in policy entrepreneurs were pointed out by American scholars. Also, developing countries are known to have different policy streams. Despite these critics and the down-turning tendency of citations, the Policy Stream Model is still an influential theory in social sciences. For example, Kagan (2019) adopted the multiple streams model to the policy of a renewable energy portfolio standard in Hawaii, and Huber-Stearns et al. (2019) analyzed a case of institutional innovation in forest watershed governance using a multiple streams approach [23,27].

3.2. Rational Decision-Making Theories

The above sub-section has outlined the history of irrational decision-making theories and briefly introduced a couple of major models. In this part, the opposite viewpoint will be delineated: a Procedural Rationality Model for policy processes. Rationality is definitely a very ambiguous notion in the fields of philosophy and cognitive psychology. In fact, there have been theoretical controversies about whether rationality can be reliably defined or not [28]. In contrast, there are overall agreements about rationality among social scientists. In the mid-1950s, Herbert Simon conceptualized procedural rationality to understand how public choices are made by governments [29]. Thereafter, rationality in policy processes has been defined as a series of reasonable and logical decision-making [30].

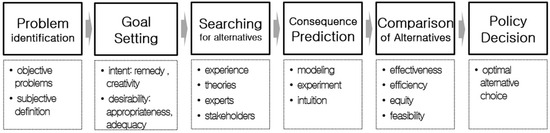

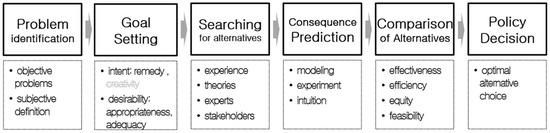

This rational policy-making process consists of six steps: problem identification, goal setting, searching for alternatives, consequence prediction, comparison of alternatives, and policy decision. First, public policies certainly start from social problems because governments are the only authorities that ought to solve their public issues by using policies. Therefore, problem identification is the first step of policy processes. In this step, the identification is characterized by the objectivity of problems and the subjectivity of their definitions. Second, policy goals are set after identifying social problems. In this step of goal setting, the intent of policies is classified as either remediation or creativity. Also, the desirability of the goal can be evaluated using criteria such as appropriateness and adequacy. Third, governments need to search for instruments to attain policy goals. In this step of searching for alternatives, policy instruments are derived from experiences, theories, experts, and stakeholders. Fourth, the next step is consequence prediction. After exploring policy instruments, the results of individual alternatives should be anticipated using experimentation, modeling, and intuition. Fifth, a comparison of alternatives is necessary before the final decision-making. In this step, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and feasibility can be adopted as criteria for assessment. Sixth, policy decision is the last step. Through this, an optimal policy alternative can be finally chosen [31].

This study utilizes these six steps for analyzing the procedural rationality of the Korean policies on fine particulate matter. Namely, if the procedure of policy-making in South Korea followed these steps properly, the policy processes could be regarded to be rational. In contrast, if the Korean government did not adopt these six steps in general, the fine dust policy of the country would be judged to be irrational. Figure 3 schematizes a framework for the analysis of procedural rationality [28].

Figure 3.

Analysis framework for evaluating procedural rationality.

Before utilizing this analytic framework, it is necessary to narrow down and confirm the scope of this study. First, the scope of contents is restricted to fine particulate matter, especially ultra-fine dust (PM2.5). Second, the scope of time corresponds to the period from 2013 to 2020, as illustrated in Section 2. Third, the scope of methodologies is limited to procedural rationality, not substantial rationality. In the next section, the analysis framework will be applied within these research scopes.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Problem Identification

Governments always encounter plenty of social problems. Among these, only a few issues are chosen as worthwhile policy agendas. When selecting issues, public administrations consider two priorities, namely the objectivity of the problems and the subjectivity of their definitions. Firstly, with regard to fine particulate matter in South Korea, there was an objectively identified problem in 2019. The annual mean concentration of PM2.5 in Seoul was 24.8 µg/m3, which was significantly higher than 10 µg/m3, the target of the World Health Organization [32]. The international organization suggested four targets of PM2.5 in its report entitled “Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide” [33]. In detail, Interim Targets 1, 2, 3, and the Air Quality Guideline are 35, 25, 15, and 10 µg/m3, respectively. Among these, the Korean government adopted the level of Interim Target 2 as a national standard in 2013. Furthermore, the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer), an affiliated sub-organization of the WHO, announced in the same year that ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) was included as a carcinogen that provokes lung cancers [34]. Thereafter, the Ministry of Environment in South Korea strengthened the standard of PM2.5 to 15 µg/m3 in accordance with Interim Target 3 in 2015. As shown in this case, there was indisputable air pollution in Korea with respect to ultra-fine dust, including PM2.5.

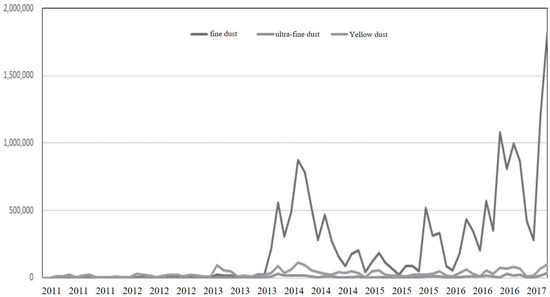

Secondly, policy-making processes need their own subjective definition. If a majority of Koreans have no interest in environmental pollution and ignore the issue of fine particles, politicians would not legislate any related bills and not allocate budgets at all. However, Korean voters were very sensitive to the issue of air pollution. Figure 4 indicates the number of articles on fine dust and ultra-fine dust in newspapers from 2011 to 2017. Namely, right after the two announcements from the Ministry of Environment in 2013 and 2015, Korean citizens revealed enormous concerns about PM10 and PM2.5. Owing to this large interest from the public, government officials and politicians were able to enact and revise the law on fine particulate matter [35]. Therefore, with regard to problem identification, there were two fulfilled conditions: objective problems and subjective definitions.

Figure 4.

The number of articles on fine dust and ultra-fine dust. Source: [35].

4.2. Goal Setting

In the next step, it is necessary to distinguish between the two intents of policy: remediation or creativity. Here, creative goals are targets that have not been encountered previously. As times are rapidly changing in this day and age, governments should follow trends and adapt to a new transition. For example, public administrations could aim to make a new future, such as the era of artificial intelligence or the fourth industrial revolution. However, the goals of environmental policies, including fine dust programs, are not creative at all.

In contrast, the policy goals regarding fine particulate matter are a sort of remedy. Surely, there had rarely been air pollution before industrialization. In fact, fine particles mostly originate from two major sources: coal-fired power plants and internal combustion engines. In the Seoul Metropolitan Area, the visibility impairment problem originating from fine particulate matter has received considerable attention [36]. Consequently, the purpose of the policies was to restore the air quality from polluted to clean. Therefore, the type of policy goals for ultra-fine dust could be classified as a remedy.

In this step of goal setting, it is also necessary to examine the desirability of the policy. The generally accepted definition of public policy is the effort of governments to attain desirable societies. Here, policy goals are related and indispensable to the desired state. Concretely, desirability is divided into two sub-components: appropriateness and adequacy. These two desirability components regarding ultra-fine particles were enunciated in the government report entitled the Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management [37].

First, the policy goal of fine particulate matter was appropriate because clean air is a prerequisite for a healthy life. As illustrated in Section 1, air pollution has been the most serious anxiety for Korean citizens. Therefore, reducing the PM2.5 concentration as a policy goal was obviously desirable. Second, the policy goal of eliminating fine particles was also adequate. After the Ministry of Environment set the target concentration at 25 µg/m3 in 2013, the government strengthened this standard again up to 15 µg/m3 in 2015, only two years after the first announcement. According to the official report, the Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management, the ministry anticipated that this target was achievable [38].

4.3. Searching for Alternatives

After setting policy goals, governments should search for feasible means to achieve the goals. It is widely accepted that there are four major sources for policy alternatives: experiences, theories, experts, and stakeholders. First, the Korean government had already acquired experiences from itself and others. In 2016, the United Nations Environment Programme published a report on air pollution policies and programs around the world [38]. Other countries’ policies and practices in this report were exemplary of the Korean fine dust policy. Particularly, South Korea referred to the experience of the United States because it has strong autonomy at the level of municipalities in the field of air pollution policies related to fine particles [39]. Additionally, previous domestic policies about PM10 in the First Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Control Master Plan, illustrated in Section 2, were also helpful and beneficial to the ultra-fine dust policy [40].

Moreover, the ministry utilized theories and experts from the national research institute, the Korea Environment Institute, to obtain policy alternatives. This institute was first established as the Korea Environmental Technology Research Institute in 1992, and the current name was approved in 1997. Currently, it has 224 staff, including 140 experts. In particular, this institute specializes in supporting environmental policies on behalf of the government, and the personnel consists of scientists, engineers, economists, and so forth.

Actually, the institute analyzed policy alternatives by using theories and scientific models, and two research reports were published. In the first report, the physical characteristics of PM2.5 were examined, the health impacts of fine particulate matter were estimated, and a roadmap for management programs was designed [41]. The second report formulated fine dust policies at the level of municipalities, particularly in industrial and residential cities such as Ulsan, Gwangju, and Daejeon [42].

Also, the Ministry of Environment held two official conferences in 2014 and 2016 to collect policy alternatives from stakeholders including private companies, civil activists, and local residents. Their suggestions were reflected in government policies. In addition, this open-to-the-public policy process was able to strengthen social trust between the government and private sectors. Consequently, this sort of partnership was helpful in achieving effective implementation [43].

4.4. Consequence Prediction

After collecting policy alternatives from various sources, governments need to predict the consequences of individual policy means. At this step, experts utilize modeling methods, scientific experiments, and their intuitions. First, researchers applied atmospheric models to simulate the behavior of pollutants in the air. To obtain more accurate results, they had to collaborate with Chinese experts because fine dust is a transboundary pollutant. However, Chinese authorities were initially not cooperative because the government denied its responsibility. Therefore, South Korea alternatively looked for joint research with the United States. Finally, the Chinese government decided to collaborate, and the North-East Asia Clean Air Partnership was launched in 2018. Other international channels such as the Tripartite Environmental Ministers Meeting and Tripartite Policy Dialogue on Air Pollution were also activated. Owing to this multilateral partnership, Korean and Chinese researchers were able to develop simulation models for fine dust in conjunction [8].

Additionally, artificial rain experiments were conducted 29 times from 2016 to 2018 in the metropolitan area, and one experiment was implemented in 2019 over the Yellow Sea. The purpose of these numerous experiments was to identify whether artificial rain could eliminate fine dust or not. Approximately half of the total amount of fine particles was presumed to originate from China. Therefore, if the Korean government could remove fine dust over the sea, air pollution could be eased in Seoul and across the Korean peninsula. However, the effect of the experiments was negligible, disappointing the Ministry of Environment. Consequently, the government excluded artificial rain from potential policy alternatives [44].

The ministry also utilized experts’ intuitions. In some circumstances, governments are inevitably dependent on specialists because computer models cannot perfectly predict the future. Therefore, professional intuitions from experts could be the only method to rely on for anticipation. Actually, the Korean government listened attentively to opinions from domestic and foreign experts. This was because the fine dust issue is not restricted to South Korea but also involves neighboring countries. In this complicated international situation, experts’ intuitions had the potential to be especially valuable.

4.5. Comparison of Alternatives

The next step after predicting consequences involves a comparison of alternatives. In the previous step, the environmental impacts, technical possibilities, and economic costs of potential policy alternatives are estimated. Then, governments need to compare individual alternatives before finally deciding on policy means. In this step, criteria such as effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and feasibility could be utilized.

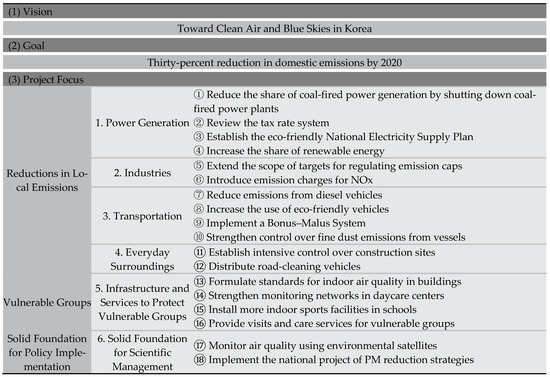

Among these, effectiveness is a basic criterion with regard to public policy. Indeed, in the Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management, the government considered whether individual fine dust programs could attain the policy goals or not [34]. Subsequently, it is necessary to examine efficiency because governments always have financial constraints. In South Korea, the Ministry of Economy and Finance participated in the comprehensive plan and reviewed costs and budgets. If there had been no agreements from the financial ministry, the plan for fine particles would not have been confirmed. Additionally, the Korean government took equity into account. As seen in Figure 5, the comprehensive plan included considerate and meticulous protection of vulnerable groups such as infants, elderly people, and disabled people. At last, feasibility was also reviewed thoroughly. For example, other ministries such as MOTIE (the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy) and MOLIT (the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation) participated in and were associated with achieving the policy goals regarding fine dust.

Figure 5.

Strategic process in the Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management. Source: [37].

4.6. Policy Decision

Based on the comparison of alternatives, governments decide on the optimal policy. With respect to the ultra-fine dust of PM2.5 in South Korea, there were two major decisions. Of course, there were other related policies in advance of these two decisions. For instance, the Special Act on the Improvement of Air Quality in Seoul Metropolitan Area was introduced in 2003. Owing to this act, the First Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Control Master Plan was also able to be established, as illustrated in Section 2. Nevertheless, the first master plan just focused on relatively large fine dust (PM10) and did not include any regulations concerning ultra-fine particles (PM2.5). As the main topic of this study is only PM2.5, subsequent policies are more important with regard to fine particulate matter. Therefore, only the two recent policy decisions in 2013 and 2018 are considered in this step.

At first, the Second Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Control Master Plan was declared in 2013, and the Korean government focused on ultra-fine particles and commenced controlling the emission of PM2.5 in earnest. In 2018, the Special Act on the Reduction and Management of Fine Dust was enacted apart from other existing ordinances. This act empowered the government to solve the problem of ultra-fine dust more effectively. As indicated in Figure 6, the government additionally applied stricter guidelines for PM2.5 based on this act. Consequently, Korean citizens began to directly experience stern regulations even in their everyday lives. Actually, a recent press release from the Ministry of Environment shows that the concentration of fine dust recorded its lowest level, 21.0 µg/m3, in April 2024, while it was 24.4 µg/m3 in April 2019 when the regulation started. The ministry insisted that this improvement meant that the environmental policy was effective.

Figure 6.

Structure of the Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management. Source: [37].

4.7. Synthesis of Analysis Results

The procedural rationality of the Korean policy on ultra-fine dust has been analyzed above. Six steps of policy processes were adopted as a framework of analysis: problem identification, goal setting, searching for alternatives, consequence prediction, comparison of alternatives, and policy decision. To summarize, objective problems with regard to PM2.5 were ascertained, and a subjective definition in public perception was verified at the problem identification step. The intent of the policy was a remedy, and targets were deemed desirable at the goal setting step. The Ministry of Environment collected policy means from experiences, theories, experts, and stakeholders at the searching for alternatives step. To anticipate future results of individual alternatives, research institutes utilized modeling, experiments, and intuitions at the consequence prediction step. Also, the government accepted effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and feasibility as criteria for assessment in the comparison of alternatives step. Finally, there were two major decisions made in 2013 and 2018 at the policy decision step. Figure 7 indicates the synthetic results of this analysis in a diagram.

Figure 7.

Results of analysis. Note: a gray strikethrough indicates a sub-component that was excluded and not applicable.

5. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research Works

This study aimed to review the rationality of the ultra-fine dust policies in South Korea. The academic interest in this research was stimulated by a couple of previous studies: namely, Kim and Lee (2019) judged that the environmental programs enacted to reduce the emissions of fine particles had failed [13]; furthermore, Choi and Kim (2016) insisted that the fundamental reason for this policy failure was caused by path dependency [14]. In these two studies, the authors asserted that Korean policies with regard to fine particulate matter were improperly designed, irrationally executed, and inappropriately evaluated by the government. In contrast, this study attempted to refute their opinions by adopting procedural rationality as a framework of analysis and proved that the Korean policy scheme was significantly reasonable and rational.

Even though only one case of the Seoul Metropolitan Area was analyzed in this study, the results of the analysis could apply to other cities. Particularly, megacities in developing countries such as China, India, and Vietnam suffer from severe air pollution because of coal consumption. These similar metropolitan and capital areas need to be independent from irrational and political decision-making processes with regard to air pollution. This paper suggests that they should adopt six-step rational policy procedures like the Seoul Metropolitan Area.

In conclusion, while this study demonstrates opposite findings against two previous ones, it also has several limitations. First, rationality has subjective features inevitably. In other words, rationality is not objective, and researchers’ subjective judgments cannot help but intervene in their qualitative analyses. Second, this study analyzed only procedural rationality, not substantive rationality. Nevertheless, as insisted by Simon (1976), procedural rationality is more important, and it is a central concept for policy analysis owing to the imperfections of substantive rationality [45]. For these reasons, this study just focused on procedural rationality. Lastly, follow-up studies could be expanded in other metropolitan cities in developing countries or compare the results of this analysis with other domestic cities in South Korea. In addition, research on substantive outcomes of air pollution regulations could be meaningful and helpful for policy-makers by utilizing scientific simulations and experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20224000000150).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Apergis, N.; Ozturk, I. Testing Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis in Asian countries. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Kim, E.; Woo, Y. The Relationship between Economic Growth and Air Pollution—A Regional Comparison between China and South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Hearne, R.; Lee, K.; Roberts, D. The relation between water pollution and economic growth using the environmental Kuznets curve: A case study in South Korea. Water Int. 2015, 40, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwag, Y.; Kim, M.-H.; Oh, J.; Shah, S.; Ye, S.; Ha, E.-H. Effect of heat waves and fine particulate matter on preterm births in Korea from 2010 to 2016. Environ. Int. 2020, 147, 106239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, B.-U.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, S. Sensitivity of fine particulate matter concentrations in South Korea to regional ammonia emissions in Northeast Asia. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Ho, C.-H.; Chang, L.-S.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.-K.; Kim, S.-J. Dominance of large-scale atmospheric circulations in long-term variations of winter PM10 concentrations over East Asia. Atmos. Res. 2020, 238, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnka, D. Policies, Regulatory Framework and Enforcement for Air Quality Management: The Case of Korea; Environment Working Paper No. 158; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE (Ministry of Environment). ECOREA: Environmental Review 2015, Korea; MOE (Ministry of Environment): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- Ministry of Environment (MOE). Emission Reduction Program for In-Use Diesel Vehicles. Korea Environ. Policy Bull. 2008, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marval, J.; Tronville, P. Ultrafine particles: A review about their health effects, presence, generation, and measurement in indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 108992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Yoo, J.Y.; Park, C.J. Recent Status and Policy of Fine Dust in the Metropolitan Area of Korea. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2018, 9, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Lee, J.W. Why did Seoul’s Free Public Transportation Program for Reducing Fine Particulate Matter Fail?: A Political Management Perspective. Korean J. Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 22, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Kim, C. Path Dependency and Social Amplification of Risk in Particulate Matter Air Pollution Management and its Implications. J. Korean Reg. Dev. Assoc. 2016, 28, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, P. Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues, 2nd ed.; Macmillan International Higher Education; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.D.; March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, D.A. Policy Entrepreneurs, Issue Experts, and Water Rights Policy Change in Colorado. Rev. Policy Res. 2010, 27, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, I.H. The Development of Renewable Electricity Policy in the Province of Ontario: The Influence of Ideas and Timing. Rev. Policy Res. 2007, 24, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N.; Zahariadis, N.; Zohlnhöfer, R. The Multiple Streams Framework: Foundations, Refinements, and Empirical Applications. In Theories of the Policy Process; Weible, C., Sabatier, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. “The World Changed Today”: Agenda-Setting and Policy Change in the Wake of the September 11 Terrorist Attacks. Rev. Policy Res. 2004, 21, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.; Kapoor, T.; McLaren, L. Politics, Science, and Termination: A Case Study of Water Fluoridation Policy in Calgary in 2011. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 36, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.A. Multiple Streams in Hawaii: How the Aloha State Adopted a 100% Renewable Portfolio Standard. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 36, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, D.J. Earth Day and Its Precursors: Continuity and Change in the Evolution of Midtwentieth-Century U.S. Environmental Policy. Rev. Policy Res. 2008, 25, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; McConnell, A.; Perl, A. Streams and stages: Reconciling Kingdon and policy process theory. Eur. J. Political Res. 2014, 54, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Morris, J.C. Kingdon’s “Streams” Model at Thirty: Still Relevant in the 21st Century? Politics Policy 2016, 44, 608–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber-Stearns, H.R.; Schultz, C.; Cheng, A.S. A Multiple Streams Analysis of Institutional Innovation in Forest Watershed Governance. Rev. Policy Res. 2019, 36, 781–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.R.; Rawling, P. The Oxford Handbook of Rationality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, G.; Herbert, A. Simon and the concept of rationality: Boundaries and procedures. Braz. J. Political Econ. 2010, 30, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.-H.; Oh, S.-M. An Analysis on Rationality in Policy Making Process: Focusing on the Case of Seoul Energy Corporation. Korean J. Local Gov. Stud. 2020, 24, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQAir. 2019 World Air Quality Report: Region & City PM2.5 Ranking; IQAir: Goldach, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Air Quality Guidelines for Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Air Pollution and Cancer; IARC Scientific Publications: Lyon, France, 2013; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M. An Analysis of Social Data characteristics about ultra-fine dust and future policy demand. Mag. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2017, 17, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, S.D.; Lee, B.K.; Han, J.S. Fine particulate matter characteristics and its impact on visibility impairment at two urban sites in Korea: Seoul and Incheon. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment (MOE). Comprehensive Plan on Fine Dust Management. Korea Environ. Policy Bull. 2018, 15, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Actions on Air Quality: Policies & Programmes for Improving Air Quality around the World; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.-H. Review of PM-related Air Quality Improvement Policies of United States for PM-related Air Quality Improvement of Metropolitan Region in Korea. J. Korean Soc. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 25, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jung, C.H.; Kum, H.S.; Kim, Y.P. The Revisit on the PM10 Reduction Policy in Korea: Focusing on Policy Target, Tools and Effect of 1st Air Quality Management Plan in Seoul Metropolitan Area. J. Environ. Policy Adm. 2017, 25, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S. A Study on the Health Impact and Management Policy of PM2.5 in Korea (I); Korea Environment Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S. A Study on the Health Impact and Management Policy of PM2.5 in Korea (II); Korea Environment Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T. Air Quality and Regional Co-operation in South Korea. Global Asia 2019, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.; Jung, W.; Chae, S.; Ko, A.; Ro, Y.; Chang, K.; Seo, S.; Ha, J.; Park, D.; Hwang, H.; et al. Analysis of Results and Techniques about Precipitation Enhancement by Aircraft Seeding in Korea. Atmosphere 2019, 29, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. From substantive to procedural rationality. In Method and Appraisal in Economics; Spiro, L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).