Mechanisms of Media Persuasion and Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth Driving Green Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Underpinning Theory

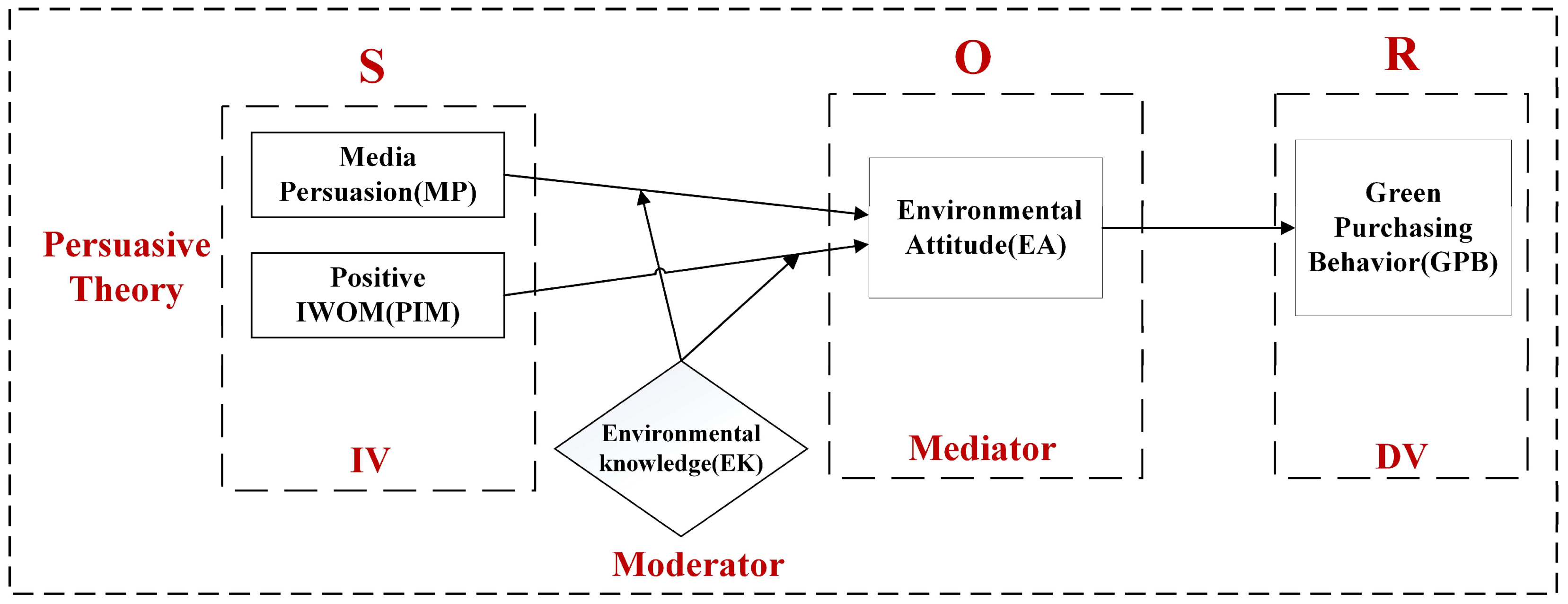

2.1.1. S–O-R

2.1.2. Persuasion Theory

2.2. Green Purchasing Behavior (GPB)

2.3. Media Persuasion (MP)

2.4. Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth (PIM)

2.5. Environmental Attitude (EA)

2.6. Environmental Knowledge (EK)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Instrument Development and Measures

3.2. Critical Organisms of Selecting Eco-Friendly Clothing

3.3. Sample and Data Collection Procedures

3.4. Methods of Analysis

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Normality Test

4.2. Common Methodological Biases

4.3. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.3.1. Reliability and KMO Test

4.3.2. Validity Tests

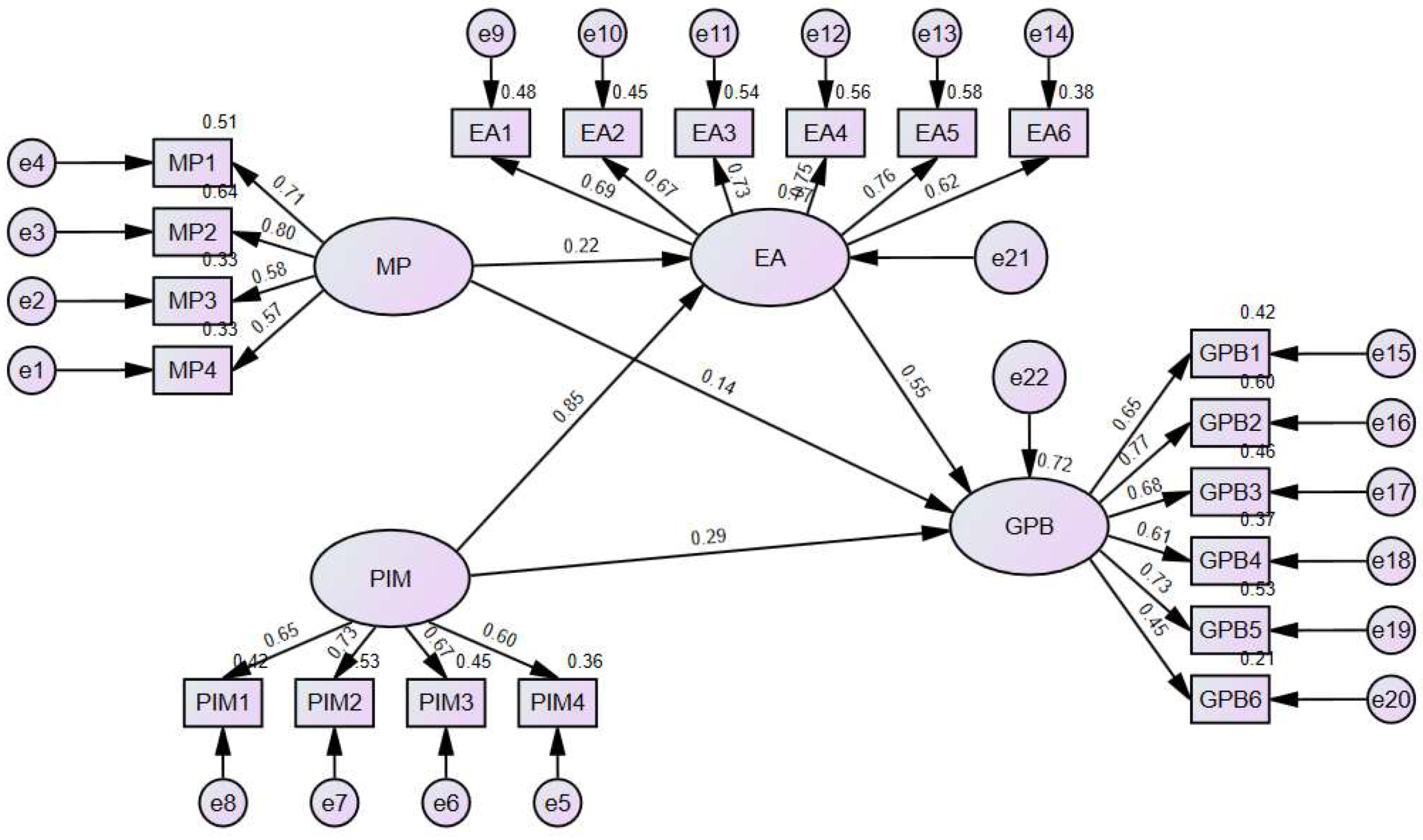

4.4. SEM Results

4.5. Mediating and Moderating Effects

4.5.1. Mediating Effects of Environmental Attitude (EA)

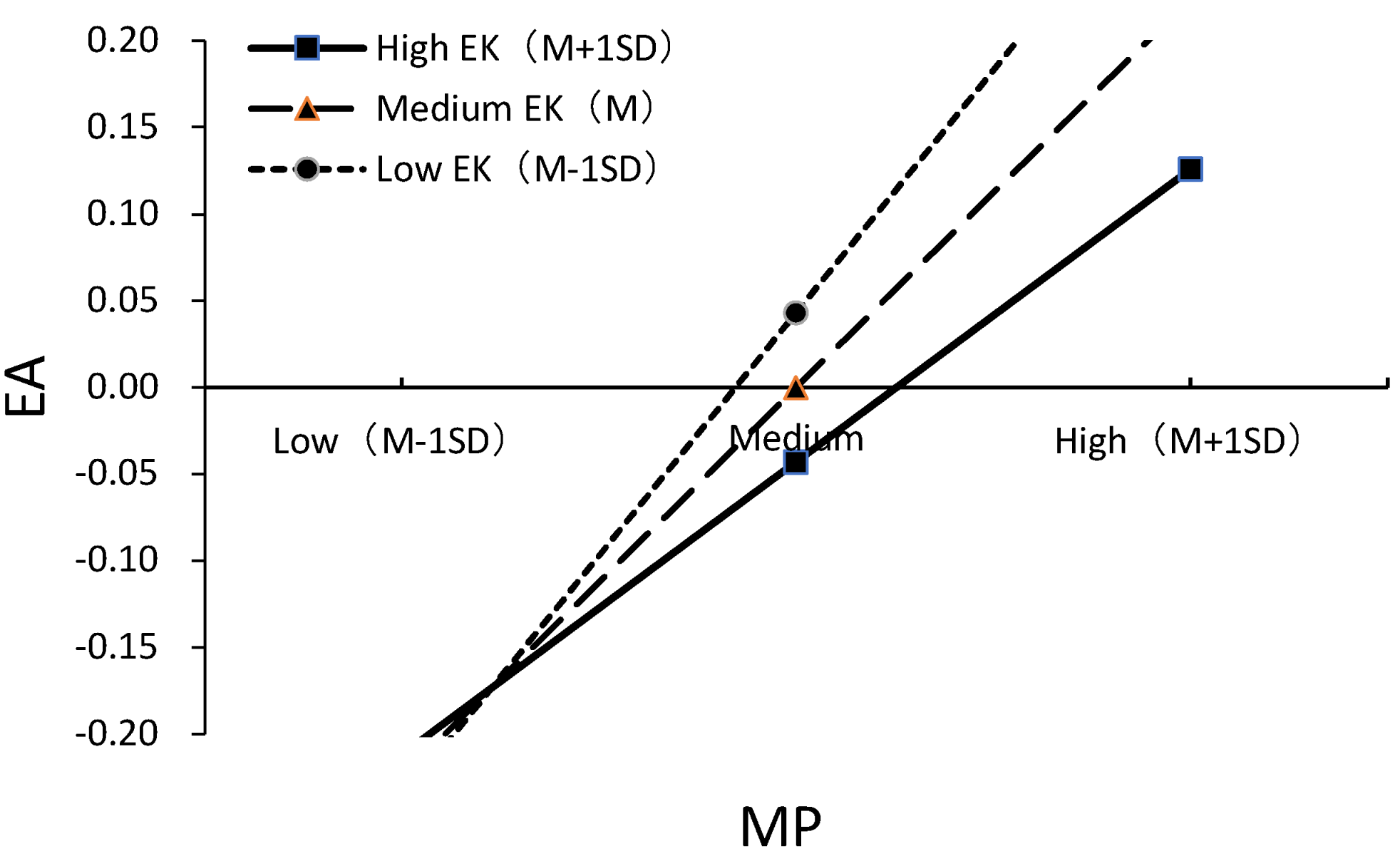

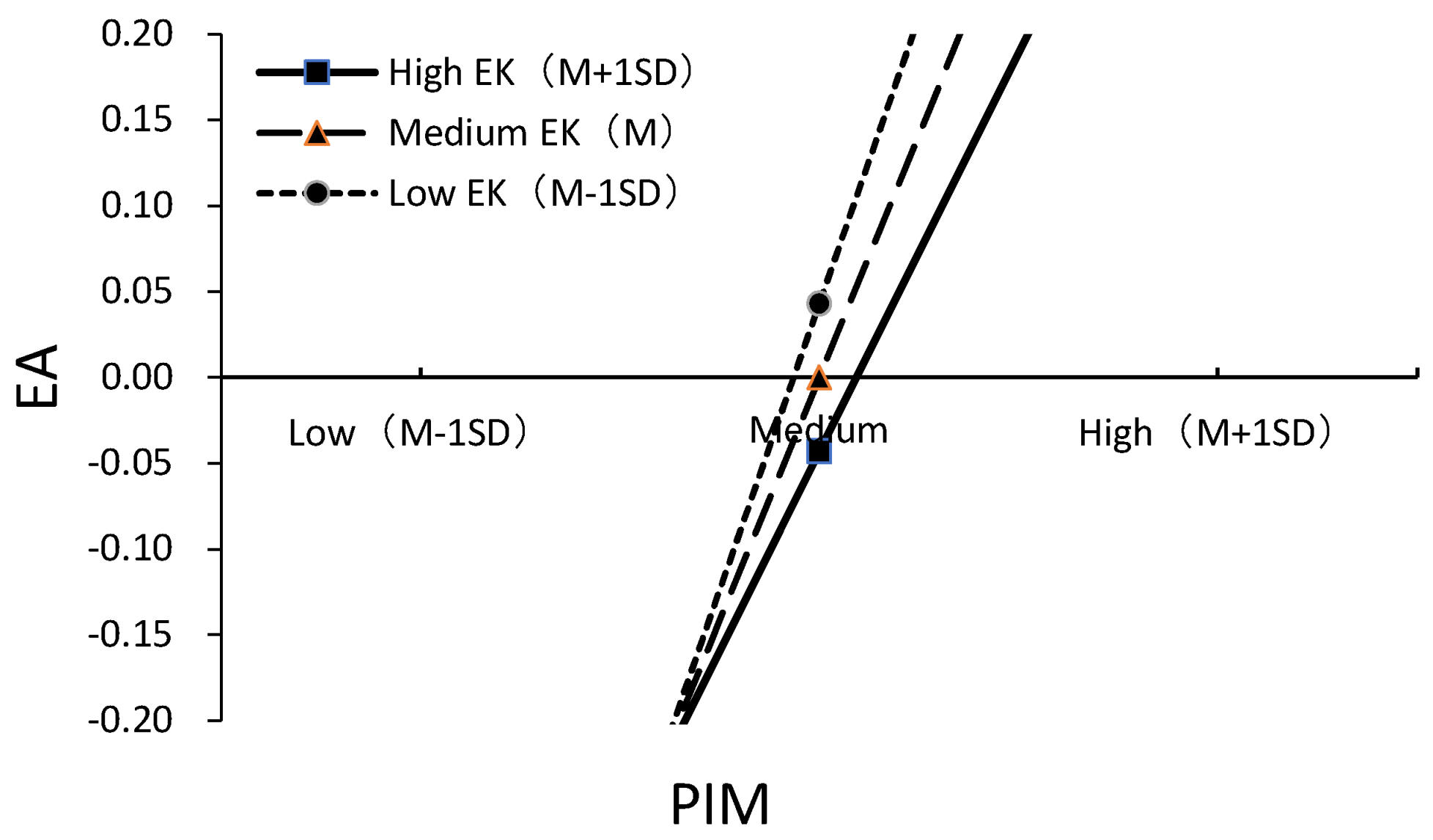

4.5.2. Moderating Effects of Environmental Knowledge (EK)

4.5.3. Moderated Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. The Potential Implications for Managerial Practice

6.2.1. From a Governmental Perspective

6.2.2. From a Corporate Perspective

7. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measure | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Media persuasion | I have seen information about the environmental crisis on TV. | [62] |

| I recently observed an advertisement that highlighted the environmental crisis. | ||

| I heard about the environmental crisis on the radio. | ||

| I was browsing the internet for information on the environmental crisis. | ||

| Positive IWOM | I think green cars have a lot of positive reviews online. | [99] |

| I make purchasing decisions with useful information from positive word-of-mouth about the product. | ||

| Positive reviews from consumers who have already purchased will make me feel good about the product. | ||

| I trust the green products recommended by the green consumer role models. | ||

| Environmental attitude | I think green products help reduce pollution. | [91] |

| I think green products help protect nature. | ||

| If I had a choice, I’d go for green products. | ||

| For me, buying green products is a good idea. | ||

| I am positive about buying green products. | ||

| I think it’s important to consider ecological preservation when buying. | ||

| Environmental knowledge | I know that I buy products and packages that are environmentally safe. | [100,101] |

| I know more about recycling than the average person. | ||

| I know how to select products and packages that reduce the amount of waste in landfills. | ||

| I understand the environmental phrases and symbols on product packages. | ||

| I am confident that I know how to sort items for recycling properly. | ||

| I am very knowledgeable about environmental issues. | ||

| Green purchasing behavior | I select energy-saving products. | [102] |

| I select environmentally friendly products. | ||

| I select products with green certification labels. | ||

| I select eco-friendly products with less pollution. | ||

| I consider purchasing green products because they are less polluting. | ||

| When I have an option between two products, I select the one that causes less harm to people. |

References

- Li, W.; Shao, J. Research on Influencing Factors of Consumers’ Environmentally Friendly Clothing Purchase Behavior—Based on Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2023. Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; He, D. Research on the Mechanism of How Positive E-commerce Network Word-of-Mouth Influences Consumers Green Consumption Intention. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Keh, H.T.; Chen, J. Assimilating and Differentiating: The Curvilinear Effect of Social Class on Green Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 47, 914–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Syeda, D.; Kazmi, Q.; Anwar, A.; Ramish, M.S.; Salam, A. Impact of Green Marketing on Green Purchase Intention and Green Consumption Behavior: The Moderating Role of Green Concern. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 7, 975–993. [Google Scholar]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Rondon-Eusebio, R.F. Green Marketing Practices Related to Key Variables of Consumer Purchasing Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Singh, S.; Sharma, K.K. Relationship between environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, environmental attitude and environmental behavioural intention—A segmented mediation approach. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, X. What triggers consumers to purchase eco-friendly food? The impact of micro signals, macro signals and perceived value. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 2204–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salandri, L.; Rizzo, G.L.C.; Cozzolino, A.; De Giovanni, P. Green practices and operational performance: The moderating role of agility. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 134091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Luo, Y. Research on Green Supply Chain Performance Evaluation of Manufacturing Enterprises under ‘Double Carbon’ Targets. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 39, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, O.A.; Agag, G. Understanding Factors Affecting Consumers’ Conscious Green Purchasing Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zuo, J.; Wu, G.; Liu, B. To be green or not to be: How environmental regulations shape contractor greenwashing behaviors in construction projects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Media Persuasion Shaping and Urban Residents’ Green Purchasing Behavior-A Test of Moderating Mediating Effects. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 22, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Klein, K.; Böck, W. From Bounded Morality to Consumer Social Responsibility: A Transdisciplinary Approach to Socially Responsible Consumption and Its Obstacles. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Zhou, L.; Chien, H.; Wu, W. Promoting eco-labeled food consumption in China: The role of information. Agribusiness 2024. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Mitra, S.; Zhang, H. Research Note—When Do Consumers Value Positive vs. Negative Reviews? An Empirical Investigation of Confirmation Bias in Online Word of Mouth. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zontanos, G.; Anderson, A.R. Relationships, marketing and small business: An exploration of links in theory and practice. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2004, 7, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Alfarisi, S.; Hassan, S.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Hishan, S.S.; Al-Shami, S.; Gazem, N.A.; Mohammed, F.; Abu Al-Rejal, H.M. Fostering a clean and sustainable environment through green product purchasing behavior: Insights from Malaysian consumers’ perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Wei, H.-H.; Chi, H.-L.; Ma, Y.; Jian, I.Y. Psychological and Demographic Factors Affecting Household Energy-Saving Intentions: A TPB-Based Study in Northwest China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, J.; Su, W. The Impact of Environmental Commitment on Green Purchase Behavior in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Al Mamun, A.; Masukujjaman, M.; Yang, Q. Significance of the environmental value-belief-norm model and its relationship to green consumption among Chinese youth. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawde, S.; Kamath, R.; ShabbirHusain, R.V. ‘Mind will not mind’—Decoding consumers’ green intention-green purchase behavior gap via moderated mediation effects of implementation intentions and self-efficacy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; McMaster, R.; Newholm, T. Care and Commitment in Ethical Consumption: An Exploration of the ‘Attitude–Behaviour Gap’. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Hou, C.; Jo, M.-S.; Sarigöllü, E. Pollution avoidance and green purchase: The role of moral emotions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleitman, H.; Nachmias, J.; Neisser, U. The S-R reinforcement theory of extinction. Psychol. Rev. 1954, 61, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Distinguishing anger and anxiety in terms of emotional response factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Ao, W. Why is instant messaging not instant? Understanding users’ negative use behavior of instant messaging software. Comput. Human. Behav. 2023, 142, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Said, F.; Ting, H.; Firdaus, A.; Aksar, I.A.; Xu, J. Do Privacy Stress and Brand Trust still Matter? Implications on Continuous Online Purchasing Intention in China. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 15515–15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, R.T.; Khoddami, S. A Framework for Investigating Green Purchase Behavior with a Focus on Individually Perceived and Contextual Factors. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2023, 11, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Exploring an adverse impact of smartphone overuse on academic performance via health issues: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, M.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Dhir, A. Positive and negative word of mouth (WOM) are not necessarily opposites: A reappraisal using the dual factor theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S.C. Effects of perceived service fairness on emotions, and behavioral intentions in restaurants. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1233–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Yu, T.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-T. Identifying the critical factors for sustainable marketing in the catering: The influence of big data applications, marketing innovation, and technology acceptance model factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, P.-J.; Ren, L.; Shih, E.H.-W.; Ma, C.; Wang, H.; Ha, N.-H. Place attachment to pseudo establishments: An application of the stimulus-organism-response paradigm to themed hotels. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Hampson, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Consumer confidence and green purchase intention: An application of the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floh, A.; Madlberger, M. The role of atmospheric cues in online impulse-buying behavior. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E.; Mathur, A.; Smith, R.B. Store environment and consumer purchase behavior: Mediating role of consumer emotions. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. Using SOR framework to explore the driving factors of older adults smartphone use behavior. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, F. The influence mechanism of green advertising on consumers’ intention to purchase energy-saving products: Based on the S-O-R model. JUSTC 2023, 53, 0802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainton, M.; Zelley, E.D. Applying Communication Theory for Professional Life: A Practical Introduction, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, M.W.; Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 19, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geers, A.L.; Briñol, P.; Vogel, E.A.; Aspiras, O.; Caplandies, F.C.; Petty, R.E. The Application of Persuasion Theory to Placebo Effects. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2018, 138, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, Y.T.; Hassan, A.M.; Batbaatar, B.; Lin, P.-K. Household Waste Separation Intentions in Mongolia: Persuasive Communication Leads to Perceived Convenience and Behavioral Control. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Kuo, T.-C.; Liao, H.-T. Design for sustainable behavior strategies: Impact of persuasive technology on energy usage. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J. Influencing Human Behavior: Theory and Applications in Recreation and Tourism; Sagamore Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nadanyiova, M.; Gajanova, L.; Majerova, J. Green marketing as a part of the socially responsible brand’s communication from the aspect of generational stratification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Veas-González, I.; Naranjo-Armijo, F.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerra-Regalado, W.; Vidal-Silva, C. Advertising and Eco-Labels as Influencers of Eco-Consumer Attitudes and Awareness—Case Study of Ecuador. Foods 2024, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, G.K.; Itani, O. Factors influencing green purchasing behaviour: Empirical evidence from the Lebanese consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabkhot, H. Factors affecting millennials’ green purchase behavior: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvaka, V.; Stoforos, C.; Palaskas, T.; Botsaris, C. Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention: Dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Role of Affective Mediators in the Effects of Media Use on Proenvironmental Behavior. Sci. Commun. 2021, 43, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Xi, Y.; He, Z. Is Green Spread? The Spillover Effect of Community Green Interaction on Related Green Purchase Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policarpo, M.C.; Aguiar, E.C. How self-expressive benefits relate to buying a hybrid car as a green product. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Huanhuan, C.; Maozeng, X.U.; Fuliang, C. Reviewon Vehicle Routing Problems of Municipal Solid Waste. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Hwang, H.-G. Consumers Purchase Intentions of Green Electric Vehicles: The Influence of Consumers Technological and Environmental Considerations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, J.; Khan, M.A.S.; Jin, S.; Altaf, M.; Anwar, F.; Sharif, I. Effects of Subjective Norms and Environmental Mechanism on Green Purchase Behavior: An Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 779629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, K. Research on mechanism of consumer innovativeness influencing green consumption behavior. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2014, 5, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Sheng, G. Advertising strategies and sustainable development: The effects of green advertising appeals and subjective busyness on green purchase intention. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3421–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Keh, H.T.; Wang, X. Powering Sustainable Consumption: The Roles of Green Consumption Values and Power Distance Belief. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J.N. A Framework for the Study of Persuasion. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2022, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. The Green Purchase Behavior of Hong Kong Young Consumers: The Role of Peer Influence, Local Environmental Involvement, and Concrete Environmental Knowledge. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2010, 23, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, I.M.; Anas, A.; Farinacci, S. Dissociation of processes in belief: Source recollection, statement familiarity, and the illusion of truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1992, 121, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental Concern, Patterns of Television Viewing, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Integrating Models of Media Consumption and Effects. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, B.; Wang, B.; Ma, G. The Impact of Energy-saving Information Exposureon Green Consumption Behavior—An Empirical Study of Large-scale Text Data from E-commerce Data Platforms. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 30, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L. Mere Exposure, Psychological Reactance and Attitude Change. Public Opin. Q. 1976, 40, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.S.; Mitra, K.; Webster, C. Word-of-Mouth Communications: A Motivational Analysis. In Advances in Consumer Research; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1998; p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Broderick, A.J.; Lee, N. Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms. Decis. Support. Syst. 2012, 53, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, D. A review of research on IWOM communication mechanism. Manag. Rev. 2011, 2, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronski, J.J.; Carlston, D.E. Negativity and extremity biases in impression formation: A review of explanations. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 105, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, A.D.; Mukherjee, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Consumer Acceptance of Online Agent Advice: Extremity and Positivity Effects. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Brandão, T.; Delgado, C.; Vale, V. Brand Love, Attitude, and Environmental Cause Knowledge: Sustainable Blue Jeans Consumer Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Gong, R.; Han, G. E-word of mouth sentiment analysis for user behavior studies. Inf. Process Manag. 2022, 59, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gasawneh, J.A.; Al-Adamat, A.M. The mediating role of e-word of mouth on the relationship between content marketing and green purchase intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H. The Influence of Green Viral Communications on Green Purchase Intentions: The Mediating Role of Consumers’ Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influences. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4829–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Che, Y.; Wang, P. Empirical Research on the Effects of IWOM to Consumer Purchasing Intention: Based on the Microblogging Marketing. Int. J. Adv. Inf. Sci. Serv. Sci. 2012, 4, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-H.; Tsao, S.-H.; Chyou, J.-T.; Tsai, S.-B. An empirical study on effects of electronic word-of-mouth and Internet risk avoidance on purchase intention: From the perspective of big data. Soft Comput 2020, 24, 5713–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Viralta, D.; Veas-González, I.; Egaña-Bruna, F.; Vidal-Silva, C.; Delgado-Bello, C.; Pezoa-Fuentes, C. Positive effects of green practices on the consumers’ satisfaction, loyalty, word-of-mouth, and willingness to pay. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Berenguer, J. Environmental Values, Beliefs, and Actions. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J. The environmental attitudes inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwistianus, H.; Hatane, S.E.; Rungkat, N. Environmental Concern, Attitude, and Willingness to Pay of Green Products: Case Study in Private Universities in Surabaya, Indonesia. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 158, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Jan, M.T. The influence of collectivism on consumer responses to green behavior. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 1, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; da Costa, M.F.; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer antecedents towards green product purchase intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, H.J.P.; Barcellos-Paula, L. Personal Variables in Attitude toward Green Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Foods 2024, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulsara, H.P.; Trivedi, M. Exploring the Role of Availability and Willingness to Pay Premium in Influencing Smart City Customers’ Purchase Intentions for Green Food Products. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2023, 62, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq-Machado, L.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Gómez-Prado, R.; Cuya-Velásquez, B.B.; Esquerre-Botton, S.; Morales-Ríos, F.; Almanza-Cruz, C.; Castillo-Benancio, S.; Anderson-Seminario, M.d.L.M.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; et al. Sustainable Fashion and Consumption Patterns in Peru: An Environmental-Attitude-Intention-Behavior Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Alam, M.N.; Alshareef, R.; Alsolamy, M.; Azizan, N.A.; Mat, N. Environmental factors affecting green purchase behaviors of the consumers: Mediating role of environmental attitude. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2023, 10, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golley, F.B. A Primer for Environmental Literacy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cc2knx (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Xie, J.; Lu, C. Relations among Pro-Environmental Behavior, Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Perception, and Post-Materialistic Values in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, L.; Foti, F.; Liuzza, M.T.; Palermo, L. The role of place attachment and spatial anxiety in environmental knowledge. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 94, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tripathi, V. Green Advertising: Examining the Role of Celebrity’s Credibility Using SEM Approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 23, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Wei, X. Bridging Green Gaps: The Buying Intention of Energy Efficient Home Appliances and Moderation of Green Self-Identity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Tanwir, N.S. Do pro-environmental factors lead to purchase intention of hybrid vehicles? The moderating effects of environmental knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.B.; Jin, B. Predictors of purchase intention toward green apparel products: A cross-cultural investigation in the USA and China. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2017, 21, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Eroglu, D.; Ellen, P.S. The Development and Testing of a Measure of Skepticism Toward Environmental Claims in Marketers’ Communications. J. Consum. Aff. 1998, 32, 30–55. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23859544 (accessed on 4 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Chen, J.-Y. A Model of Green Consumption Behavior Constructed by the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, Z.; Namazova, N. Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakumbi, G.; Phiri, J. Adoption of Social Media for SME Growth in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of SMEs in the Clothing industry in Lusaka, Zambia. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 10, 3202–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Herrera, L.G.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Gallegos, A.; Benjumea-Arias, M.; Flores-Siapo, E. Technology acceptance factors of e-commerce among young people: An integration of the technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, C. The Impact of Online Environmental Platform Services on Users’ Green Consumption Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, G.P.M.; de Assis Rangel, J.J.; Shimoda, E. Sustainable last-mile distribution in B2C e-commerce: Do consumers really care? Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 3, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson College Division: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1841396 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z. The Analyses of Moderated Mediation Effects based on Structural Equation Modeling. J. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 41, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Moderation Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkzadeh, G.; Koufteros, X.; Pflughoeft, K. Confirmatory Analysis of Computer Self-Efficacy. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowsky, J.; Jager, J.; Hemken, D. Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.S.; Le, T.T.Y. ‘Why do We Buy Green Products?’ An Extended Theory of the Planned Behavior Model for Green Product Purchase Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isac, N.; Javed, A.; Radulescu, M.; Cismasu, I.D.L.; Yousaf, Z.; Serbu, R.S. Is greenwashing impacting on green brand trust and purchase intentions? Mediating role of environmental knowledge. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, I.; Manalang, L.; David, R.; Guiao, B.G. Accounting for Environmental Awareness on Green Purchase Intention and Behaviour: Evidence from the Philippines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct (N = 357) | Group | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 147 | 41.2% |

| Female | 210 | 58.8% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 103 | 28.85% |

| 25–34 | 142 | 39.78% | |

| 35–44 | 68 | 19.05% | |

| Over 44 | 44 | 12.32% | |

| Individual monthly income | 3000 and below | 68 | 19.05% |

| 3001–6000 | 54 | 15.13% | |

| 6001–9000 | 66 | 18.49% | |

| 9001–12,000 | 66 | 18.49% | |

| More than 12,000 | 103 | 28.85% | |

| Educational level | High school and below | 10 | 2.80% |

| Diploma | 20 | 5.60% | |

| Undergraduate | 254 | 71.15% | |

| Master | 73 | 20.45% |

| Contact | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Standard Error | Kurtosis | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | 3.0413 | 0.73883 | −0.086 | 0.129 | −0.648 | 0.257 |

| PIM | 3.8487 | 0.61227 | −1.068 | 0.129 | 1.509 | 0.257 |

| EA | 4.1569 | 0.59478 | −1.397 | 0.129 | 2.161 | 0.257 |

| EK | 3.5840 | 0.72944 | −0.548 | 0.129 | −0.025 | 0.257 |

| GPB | 4.1508 | 0.53896 | −1.05 | 0.129 | 1.277 | 0.257 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha (CA > 0.7) | KMO Value (KMO > 0.6) | Bartlett Test Significance (p < 0.05) | Factor Analysis Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | 0.754 | 0.737 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| PIM | 0.749 | 0.766 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| EA | 0.866 | 0.871 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| EK | 0.885 | 0.903 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| GPB | 0.829 | 0.863 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| Fitness | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 1 < NC < 3 | |||||

| Value | 1.872 | 0.049 | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.935 | 0.052 |

| Constructs | Items | SFL | TVE | CR | AVE > 0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | MP1 | 0.809 | 58.039% | 0.846 | 0.580 |

| MP2 | 0.835 | ||||

| MP3 | 0.695 | ||||

| MP4 | 0.698 | ||||

| PIM | PIM1 | 0.764 | 57.86% | 0.846 | 0.579 |

| PIM2 | 0.803 | ||||

| PIM3 | 0.741 | ||||

| PIM4 | 0.732 | ||||

| EA | EA1 | 0.764 | 60.117% | 0.900 | 0.601 |

| EA2 | 0.751 | ||||

| EA3 | 0.793 | ||||

| EA4 | 0.82 | ||||

| EA5 | 0.82 | ||||

| EA6 | 0.697 | ||||

| EK | EK1 | 0.748 | 63.780% | 0.913 | 0.638 |

| EK2 | 0.793 | ||||

| EK3 | 0.824 | ||||

| EK4 | 0.787 | ||||

| EK5 | 0.798 | ||||

| EK6 | 0.838 | ||||

| GPB | GPB1 | 0.742 | 54.341% | 0.876 | 0.544 |

| GPB2 | 0.809 | ||||

| GPB3 | 0.758 | ||||

| GPB4 | 0.719 | ||||

| GPB5 | 0.801 | ||||

| GPB6 | 0.569 |

| MP | PIM | EA | EK | GPB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | 0.762 | ||||

| PIM | 0.423 ** | 0.761 | |||

| EA | 0.455 ** | 0.727 ** | 0.775 | ||

| EK | 0.541 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.799 | |

| GPB | 0.437 ** | 0.644 ** | 0.732 ** | 0.581 ** | 0.738 |

| H | Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | MP → EA | 0.219 | 0.044 | 4.365 | *** | Supported |

| H1b | MP → GPB | 0.144 | 0.043 | 2.507 | 0.012 | Supported |

| H2a | PIM → EA | 0.852 | 0.081 | 9.246 | *** | Supported |

| H2b | PIM → GPB | 0.293 | 0.105 | 2.051 | 0.040 | Supported |

| H3 | EA → GPB | 0.553 | 0.125 | 3.739 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimate | S.E. | Bootstrap 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| H4a | MP → EA → GPB | 0.094 | 0.046 | 0.024 | 0.204 | ** |

| H4b | PIM → EA → GPB | 0.363 | 0.161 | 0.113 | 0.747 | ** |

| Mediator | EK | Mean | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA (MP→EA→GPB) | High | 0.080 (**) | 0.028 | 0.026 | 0.135 |

| Medium | 0.107 (**) | 0.037 | 0.035 | 0.179 | |

| Low | 0.133 (**) | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.226 | |

| Contrast | High–Low | −0.053 (*) | 0.025 | −0.013 | −0.003 |

| Mediator | EK | Mean | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA (PIM→EA→GPB) | High | 0.284 (**) | 0.083 | 0.121 | 0.447 |

| Medium | −0.062 (*) | 0.026 | −0.114 | −0.010 | |

| Low | 0.407 (**) | 0.129 | 0.155 | 0.660 | |

| Contrast | High–Low | −0.124 (*) | 0.053 | −0.227 | −0.020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Z.; Rosbi, S.; Amlus, M.H. Mechanisms of Media Persuasion and Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth Driving Green Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156521

Yu Z, Rosbi S, Amlus MH. Mechanisms of Media Persuasion and Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth Driving Green Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156521

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Zeng, Sofian Rosbi, and Mohammad Harith Amlus. 2024. "Mechanisms of Media Persuasion and Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth Driving Green Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156521

APA StyleYu, Z., Rosbi, S., & Amlus, M. H. (2024). Mechanisms of Media Persuasion and Positive Internet Word-of-Mouth Driving Green Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 16(15), 6521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156521