Macroeconomic Determinants of Circular Economy Investments: An ECM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

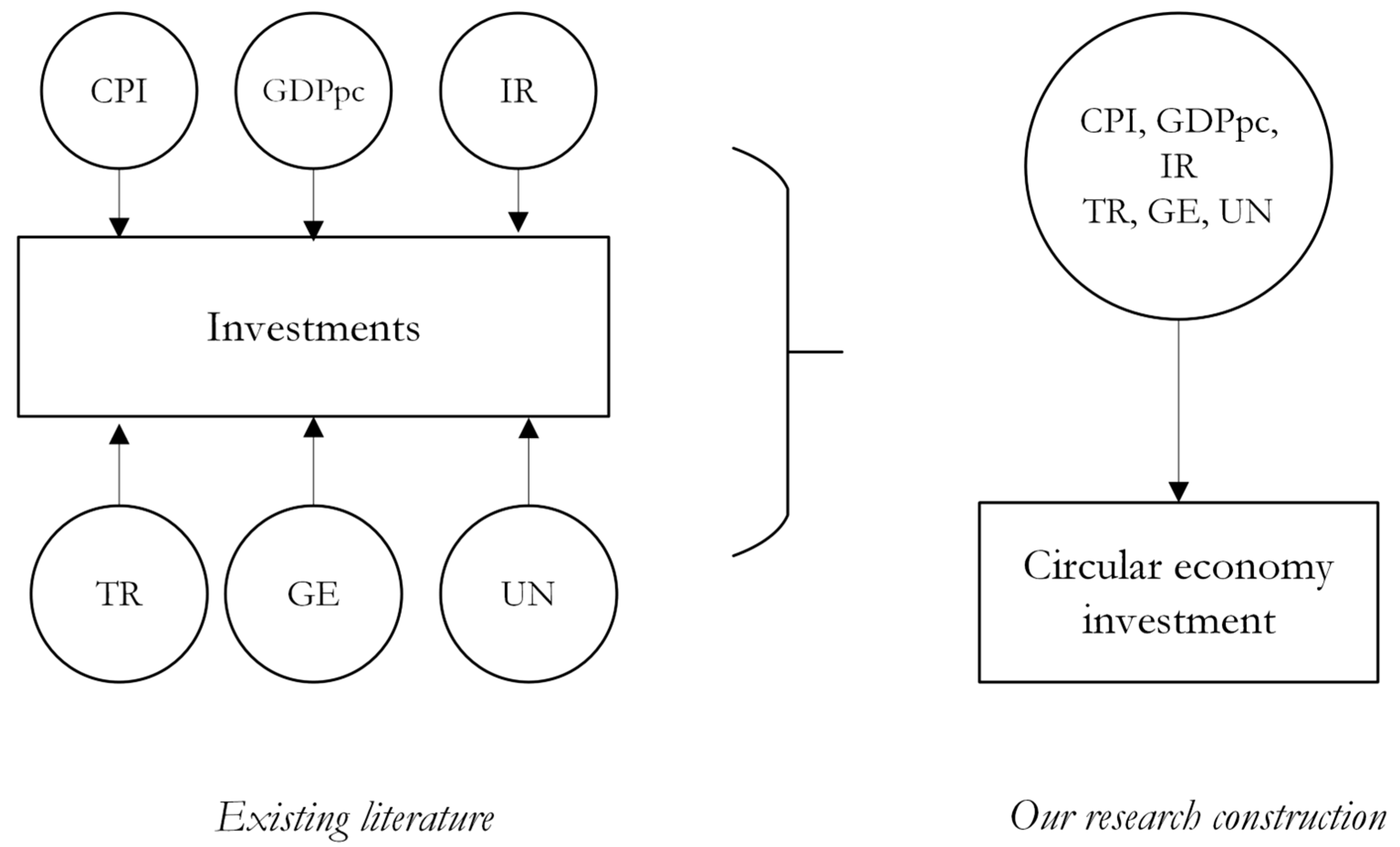

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Data and Variables

3.3. Hypotheses Development

3.4. Methodology

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, M.; Zhao, Z.Y. Causal linkages between energy investment and economic growth: A panel data modelling analysis of China. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2018, 13, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, L.; Compernolle, T.; Hagspiel, V.; Kort, P.; Oliveira, C. Stepwise Investment in Circular Plastics under the Presence of Policy Uncertainty; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 83, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Wang, Y.; Ali, S.; Haider, M.A.; Amin, N. Shifting to a green economy: Asymmetric macroeconomic determinants of renewable energy production in Pakistan. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, L.; Madlener, R. A pathway to green growth? Macroeconomic impacts of power grid infrastructure investments in Germany. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foye, V.O. Macroeconomic determinants of renewable energy penetration: Evidence from Nigeria. Total Environ. Res. Themes 2023, 5, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, K.B.; Lanre Ibrahim, R. Bayesian model averaging approach of the determinants of foreign direct investment in Africa. Int. Econ. 2022, 172, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Jahan, S.M. Determinants of international development investments in renewable energy in developing countries. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T.; Damásio, B. Leveraging the circular economy: Investment and innovation as drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirović, V.; Kalaš, B.; Inđić, M. The determinants of government expenditures in Serbia: The application of ARDL model. Anal. Ekon. Fak. Subotici 2023, 59, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Effects of government expenditure on private investment: Canadian empirical evidence. Empir. Econ. 2005, 30, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinevičienė, L. Testing the Relationship between Government Expenditure and Private Investment: The Case of Small Open Economies. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bairam, E.; Ward, B. The externality effect of government expenditure on investment in OECD countries. Appl. Econ. 1993, 25, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlo, T.; Oyeleke, O.J. Effects of Government Expenditure on Private Investment in Nigerian Economy (1980–2016). Emerg. Econ. Stud. 2018, 4, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirović, V.; Kalaš, B.; Andrašić, J.; Milenković, N. Implications of Environmental Taxation for Economic Growth and Government Expenditures in Visegrad Group countries. Polit. Ekon. 2023, 71, 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirović, V.; Kalaš, B.; Milenković, N.; Andrašić, J. Different modelling approaches of tax revenue performance: The case of Baltic countries. Economics 2023, 26, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vence, X.; López Pérez, S.d.J. Taxation for a circular economy: New instruments, reforms, and architectural changes in the fiscal system. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milios, L. Towards a Circular Economy Taxation Framework: Expectations and Challenges of Implementation. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Ha, N.; Tan Minh, P.; Binh, Q.M.Q. The determinants of tax revenue: A study of Southeast Asia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2026660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ðurović Todorović, J.; Đorđević, M.; Mirović, V.; Kalaš, B.; Pavlović, N. Modeling Tax Revenue Determinants: The Case of Visegrad. Economies 2024, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.; St. Aubyn, M. Economic growth, public, and private investment returns in 17 OECD economies. Port. Econ. J. 2019, 18, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Lobonţ, O.R.; Meng, Q. Effectiveness of Principal-Component-Based Mixed-Frequency Error Correction Model in Predicting Gross Domestic Product. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P.; Loza, A. Short and Long Run Determinants of Private Investment in Argentina. J. Appl. Econ. 2005, 8, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyuan, L.; Khurshid, A. The effect of interest rate on investment; empirical evidence of Jiangsu Province, China. J. Int. Stud. 2015, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, A.A.; Scandurra, G. Investments in renewable energy sources in countries grouped by income level. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2016, 11, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvelli, G. The long-run effects of government expenditure on private investments: A panel CS-ARDL approach. J. Econ. Financ. 2023, 47, 620–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, R.K. Determinants of private sector investment in a less developed country: A case of the Gambia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1794279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.T.; Pham, A.D.; Tran, D.N. Impact of Monetary Policy on Private Investment: Evidence from Vietnam’s Provincial Data. Economies 2020, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghura, D.; Goodwin, B. Determinants of private investment: A cross-regional empirical investigation. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhgaliyeva, D.; Beirne, J.; Mishra, R. What matters for private investment in renewable energy? Clim. Policy 2023, 23, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurović Todorović, J.; Đorđević, M.; Zoran, T. Analysis of the Dynamics of Inflation in Serbia. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 21, 56–61. Available online: https://www.smjournal.rs/index.php/home/article/view/107 (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Ababio, J.O.-M.; Aboagye, A.Q.Q.; Barnor, C.; Agyei, S.K. Foreign and domestic private investment in developing and emerging economies: A review of literature. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2132646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, K. Determining Factors of Private Investments: An Empirical Analysis for Turkey. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2010, 11, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Omitogun, O. Investigating the crowding out effect of government expenditure on private investment. J. Compet. 2018, 10, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, C.; Muñoz-Bugarin, J. Capital investment and unemployment in Europe: Neutrality or not? J. Macroecon. 2010, 32, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon, H.T.; Katsimi, M.; Zoega, G. Investment and the long swings of unemployment. Econ. Transit. Inst. Chang. 2023, 31, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilaw Woldetensaye, W.; Sisay Sirah, E.; Shiferaw, A. Foreign direct investments nexus unemployment in East African IGAD member countries a panel data approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2146630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strat, V.A.; Davidescu, A.; Paul, A.M. FDI and The Unemployment—A Causality Analysis for the Latest EU Members. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Nikolić, M. Drivers for development of circular economy—A case study of Serbia. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, A.M.; Milenković, N.; Dudić, B.; Kalaš, B.; Radovanov, B.; Mittelman, A. Evaluating Bank Efficiency in the West Balkan Countries Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirović, V.; Kalaš, B.; Milenković, N.; Andrašić, J.; Đaković, M. Modelling Profitability Determinants in the Banking Sector: The Case of the Eurozone. Mathematics 2024, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupor, B. Investment and interest rate policy. J. Econ. Theory 2001, 98, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yip, C.K. Investment, interest rate rules, and equilibrium determinacy. Econ. Theory 2004, 23, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccarini, A. Investment sensitivity to interest rates in an uncertain context: Is a positive relationship possible? Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2007, 40, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.; Cecchetti, S.G.; Gordon, R.J. Inflation and uncertainty at short and long horizons. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act. 1990, 1990, 215–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Karolyi, G.A.; Longstaff, F.A.; Sanders, A.B. An empirical comparison of alternative models of the short-term interest rate. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 1209–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Kharb, R.; Suneja, V.; Aggarwal, S.; Singh, P.; Shahzad, U.; Saini, N.; Kumar, D. The relationship between investment determinants and environmental sustainability: Evidence through meta-analysis. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- IMF Database Data. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Pao, H.T. The causal link between circular economy and economic growth in EU-25. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 76352–76364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, S.A. The Crowding Out of Government Investment over Private Investment in Iraq: A Standard Study Using the Model (VECM) for the Period 2004-2021. Appl. Econ. Financ. 2023, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatoglu, F.Y. The Relationship between Human Capital Investment and Economic Growth: A Panel Error Correction Model. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2011, 13, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| dependent variable | |||

| INV | investment in circular economy | This indicator is part of the circular economy indicator set of the Eurostat data. It is used to monitor progress towards a circular economy. | Eurostat |

| independent variable | |||

| real GDPpc | real gross domestic product per capita | Measures the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a year divided by the total population of the considered countries. | Eurostat |

| CPI | consumer price index—annual % | Reflects the annual percentage change in the cost to the average consumer of acquiring a basket of goods and services. This basket may be fixed or updated at specified intervals, such as yearly. The CPI calculation generally uses the Laspeyres formula. | IMF data |

| GE | government expenditure—% of GDP | Government expenditure as a percentage of GDP is a metric that represents the total government spending relative to the overall economic output of a country. It is calculated by dividing the total government expenditure by gross domestic product (GDP) and multiplying it by 100 to express it as a percentage. | IMF data |

| UR | unemployment | The unemployment rate measures the percentage of the unemployed labor force seeking employment. | IMF data |

| TR | tax revenue as % GDP | Total revenue from taxes and social contributions (incl. imputed social contributions) after deduction of amounts assessed but unlikely to be collected in % of GDP. | Eurostat |

| IR | long-term interest rates | Maastricht criterion bond yields are long-term interest rates. | Eurostat |

| Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | ADF Test—Levels | ADF Test—First Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invest | 0.695 | 0.600 | 0.374 | 0.100 | 2.400 | 68.862 | 255.832 |

| Real GDPpc | 1.941 | 2.000 | 4.193 | −14.500 | 23.300 | 189.018 | 266.144 |

| Government expenditure | 44.986 | 44.981 | 7.096 | 21.230 | 66.820 | 41.026 | 97.563 |

| Unemployment rate | 8.518 | 7.400 | 4.322 | 1.900 | 27.500 | 36.663 | 144.759 |

| CPI | 2.502 | 1.921 | 2.958 | −4.478 | 19.705 | 46.731 | 83.435 |

| Tax revenue % | 36.700 | 36.533 | 6.023 | 20.616 | 49.859 | 61.657 | 148.673 |

| Interest rate | 3.093 | 3.060 | 2.533 | −0.510 | 22.500 | 46.948 | 81.306 |

| Hypothesized Number of Cointegration Equations | Trace Test | Probability | Max-Eigen Test | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 345.70 | 0.0000 | 290.70 | 0.0000 |

| At most 1 | 118.00 | 0.0000 | 103.90 | 0.0001 |

| At most 2 | 60.02 | 0.2666 | 43.26 | 0.8521 |

| At most 3 | 86.10 | 0.0036 | 86.10 | 0.0036 |

| Invest | Real GDPpc | Government Expenditure | Unemployment Rate | CPI | Tax Revenue % | Interest Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invest | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Real GDPpc | 0.0404 | 1.0000 | |||||

| Government expenditure | 0.4322 | −0.0182 | 1.0000 | ||||

| Unemployment rate | −0.3023 | −0.1697 | 0.1353 | 1.0000 | |||

| CPI | 0.3109 | 0.2059 | −0.2068 | −0.2469 | 1.0000 | ||

| Tax revenue % | 0.4428 | −0.2608 | 0.8323 | −0.0983 | −0.1692 | 1.0000 | |

| Interest rate | −0.2067 | −0.1808 | −0.0249 | 0.4400 | 0.1924 | −0.2409 | 1.0000 |

| Variable | Long-Run Model | Short-Run Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Statistic | Coefficient | t-Statistic | |

| Intercept | 1.40758 | 7.60531 *** | −0.00382 | −0.59286 |

| Government expenditure | 0.00217 | 1.82377 * | 0.00081 | 2.33994 ** |

| Unemployment rate | −0.01077 | −3.04518 *** | −0.01134 | −2.34690 ** |

| CPI | 0.00898 | 2.66646 *** | 0.01064 | 3.84328 *** |

| Tax revenue | 0.01365 | 2.63961 *** | 0.00237 | 1.67070 * |

| Interest rate | −0.01454 | −3.12399 *** | −0.00848 | −1.72498 * |

| εt−1 | −0.43592 | −11.8256 *** | ||

| Diagnostics | Long-Run Model | Short-Run Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIF test | Government expenditure | 7.5144 | 5.6445 |

| Unemployment rate | 1.0558 | 5.2422 | |

| CPI | 2.9163 | 2.0414 | |

| Tax revenue | 2.8844 | 6.7005 | |

| Interest rate | 1.1519 | 5.3132 | |

| R-squared | 0.7852 | 0.3360 | |

| F-statistic | 53.5410 *** | 6.7377 *** | |

| Hausman test | 18.3092 ** | 14.2399 ** | |

| Breusch–Pagan LM test | 53.8593 | 15.0626 | |

| Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test | 1.2655 | 1.7108 | |

| Jarque–Bera test | 4.8209 | 2.3347 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalaš, B.; Radovanov, B.; Milenković, N.; Horvat, A.M. Macroeconomic Determinants of Circular Economy Investments: An ECM Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156666

Kalaš B, Radovanov B, Milenković N, Horvat AM. Macroeconomic Determinants of Circular Economy Investments: An ECM Approach. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156666

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalaš, Branimir, Boris Radovanov, Nada Milenković, and Aleksandra Marcikić Horvat. 2024. "Macroeconomic Determinants of Circular Economy Investments: An ECM Approach" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156666

APA StyleKalaš, B., Radovanov, B., Milenković, N., & Horvat, A. M. (2024). Macroeconomic Determinants of Circular Economy Investments: An ECM Approach. Sustainability, 16(15), 6666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156666