Abstract

The sustainable finance framework implements the regulation to enhance firms’ sustainable reporting and increase market transparency in channeling funds. However, firms are under the pressure of going green and, thus, often demonstrate a propensity to environmental decoupling, which means the gap between what is told about environmental performance and what is truly done within. The main purpose of our exploratory work is to detect the environmental decoupling among sampled firms. The research problem relates to the effects of reporting requirements and aligning symptoms of environmental decoupling by comparing the increase in qualitative disclosures (talk) relative to measurable KPIs (real actions). We have empirically confirmed the potential problems of environmental decoupling within the environmental aspects other than carbon emissions. We have observed the improvement of qualitative disclosures, while the KPIs other than carbon-emission-related (use of resources and energy) confirmed no real actions. This result is aligned with the current policymakers’ focus on carbon emission reporting. Firms declare the implementation of policies and targets, but it does not fully drive real change. Our study contributes to the emerging strand of the literature on environmental decoupling, as well as offers implications for policymakers, to enhance the efficiency (and prevent environmental decoupling) within the new sustainable finance regulatory framework of the European Union.

1. Introduction

The sustainable finance framework is a relevant part of the European Green Deal policy designed in support of achieving the climate neutrality targets. The sustainable finance framework incorporates the system of reporting on a firm’s environmental activities, under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (hereafter CSRD), which entered into force on 5 January 2023 [1]. The related requirements included in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), in line with the Directive EU 2023/2772 [2], pose new challenges and remain one of the key managerial concerns within the reporting on sustainability. CSRD, as the new regulatory framework, will enhance more concern and information on a firm’s environmental performance and drive a need to change the business model. On the other hand, managers are increasingly aware that going “green” is particularly important nowadays, not only in a reputational context but also for the capital providers, as the sustainable finance framework will exert greater pressure on green investments and innovation by linking the flow of funds to climate-neutral investments.

The undeniable trend toward demonstrating “green” and sustainable practices and the related pressures and incentives lead to a growing concern about a firm’s propensity for so-called “sustainability decoupling”. Overall, sustainability decoupling refers to the communication of a firm’s sustainable practices and reflects a situation when a firm is communicating more than is being done in real terms [3,4]. Sustainability decoupling means simply a gap between “talk and walk” [5] to denote the discrepancies between what firms disclose about their sustainable performance and how far it reflects their real practices within. Sustainability decoupling is recently widely studied by scholars in the context of CSR practices [6] or one isolated aspect of sustainable performance, for instance, environmental decoupling [7]. Our study aims to contribute to the latter trend by detecting the symptoms of the potential scale of environmental decoupling among Polish listed firms.

Overall, we explore Polish firms’ environmental decoupling being motivated by prior evidence that firms tend to “talk” by expanding their sustainability reports with a large bulk of qualitative information (soft disclosures) rather than demonstrating improvement at real KPIs (key performance indicators) level. There is a strand of the literature that has been revising this issue in the aftermath of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive [8] implementation, hereafter NFRD [9,10,11]. Inspired by these works, in our explorations, we adopt a similar analytical approach by looking backward to compare the qualitative and quantitative disclosures on firms’ environmental performance before and after the implementation of the regulation. Our study uses a sample of Polish firms as these offer a unique setting for this kind of research. Poland represents a country where decarbonization on the route to achieve climate neutrality targets is particularly challenging. At the same time, it has long traditions in sustainability reporting, as before the reporting regime, the listed firms were competing to be included in the Respect index, and currently, the WIG-ESG index, the Warsaw Stock Exchange Index, dedicated to tracking the most ESG-oriented firms. Therefore, Poland is the only country that offers insight into potential environmental decoupling in European Union peripheral countries.

In our study, we test a hypothesis that in response to reporting regulation firms increased the qualitative environmental information (talk), with little effect on real actions, as confirmed by a set of KPIs. The results could have important implications for uncovering the potential existence of a managerial propensity for low responsiveness to the expected effects of regulation and fall into the strategy of environmental decoupling. This aspect of our work remains relevant given the implementation of CSRD and its relevance to achieving European Green Deal goals and climate neutrality targets. In other words, by looking backward at the effects of implementing the former mandatory regime (NFRD), our work could help to uncover the possible pathways of the inefficiency of the CSRD regulation, stemming from firms’ propensity to environmental decoupling.

The remainder of this work is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the existing literature in support of our hypothesis. In Section 3, we develop the methodical aspects of our empirical investigations by explaining the selection of variables and the sources of data used in our study. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The firm’s environmental performance disclosures are explained on the ground of legitimacy theory. Given that stakeholders are interested in firms’ environmental performance (both in the context of hindering the environment as well as supporting the environment), companies are more interested in legitimizing themselves in front of stakeholders before they could exert pressure on a firm’s performance within [12,13]. One possible strategy for a company to create a positive image could be to disclose information about its performance [14]. It was one of the major trends in developing firms’ sustainability reporting practices [15] as corporate reporting remains one of the major channels of communication between a firm and its stakeholders. There is a notable strand of the literature reviewing sustainability reporting from various angles. In this study, however, the aspect reflecting the relevance of the regulatory pressure remains in focus.

The need for a regulatory framework was driven by one of the major concerns, which was a lack of a unified framework for reporting on firms’ sustainable performance. The GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) [16] has become the first to promote a common language on the way to standardize sustainability reports [17]. In this respect, the information provided in sustainability reports maintains rigor, comparability, and auditability [18]. However, there is strong literature evidence that non-financial reporting, which is based on the GRI framework, was used predominantly for symbolic purposes. The symbolic aspects are primarily associated with greenwashing, which is defined as “selective disclosure of positive information about a company’s environmental or social performance, without full disclosure of negative information on these dimensions, so as to create an overly positive corporate image” [19]. However, there is also evidence that environmental disclosures had no impact on real environmental performance, as well as being a part of impression management [20,21].

A recent trend in this strand of the literature is the exploration of the possible existence of environmental decoupling. We define environmental decoupling in line with the existing definitions of CSR decoupling [3,5,22,23]. Environmental decoupling refers to the gap that is created between a firm’s environmental disclosures and an actual firm’s environmental performance. In other words, there is a discrepancy between positive communication about a firm’s environmental performance and its poor real environmental performance [22].

This understanding of environmental decoupling reflects the policy-practice decoupling, which occurs when the relationship between firms’ policies and practice is nonexistent or inconsistent [7,23,24]. In this aspect, environmental decoupling reflects the greenwashing practices due to disclosing positive actions while concealing negative ones [25] or not fully implementing the declared environmental policies [26].

Numerous studies on CSR or environmental decoupling were motivated by the growing evidence that the quality and completeness of corporate disclosures are questionable [27]. Some works confirmed that firms overstate their CSR performance, which is in line with legitimacy theory [22]. On the other hand, there is evidence that firms understate their activities to divert attention from the related costs [28]. Whatever the reason, these practices increase the gap between what is disclosed and the actual firm’s performance [3].

The issuance of the European Union Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) [8] is considered the first relevant step toward a unified framework of sustainability reporting [11,29]. The NFRD has mandated all large firms to issue statements on their sustainable performance. The NFRD entered into force in 2018, and since then, large firms have been mandated to disclose more extended information on their environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) aspects. The establishment of a mandatory reporting regime is driven by the regulatory role of disclosure and the related expectation that this will change the firm’s behavior as a consequence of increased stakeholder pressure [30,31]. After a few years of the NFRD reporting regime, numerous scholars attempted to capture if the regulatory role of the NFRD was truly achieved. There is evidence that the effect was achieved if we consider the extension of the information provided within the sustainability reports and the improvement of the firm’s ESG ratings [29,32]. This evidence was, however, accompanied by some contradicting evidence [10] or the evidence on the relevant gaps in the scope of the information disclosed by firms under the NFRD regime. In particular, there is evidence that quantity prevails over quality [11,33]. For Poland, Klimczak et al. [34] have confirmed that firms’ NFRD-related disclosures were bluntly positive and, at the same time, lacked information reflecting performance. The management response to the growing pressure on disclosures appears to respond to the need of investors with qualitative information and, at the same time, avoid setting goals and reporting effects. Klimczak et al. [34] evidence signalizes the possible presence of decoupling among Polish listed firms.

These observations have led to the question of whether the mandatory reporting requirements and its regulatory role helped to avoid a firm’s tendency to legitimize its environmental performance. Based on the previous empirical evidence, we pose a hypothesis that after the NFRD regulation, Polish firms improved their disclosures reflecting environmental performance in qualitative terms, with no improvement reflecting real actions within. The confirmation of our hypothesis would indicate the possible symptoms of environmental decoupling, where talk (qualitative disclosures) prevails over real actions.

3. Research Design and Method

Our empirical study is designed to explore the potential symptoms of environmental decoupling by looking backward and verifying the effects of the NFRD implementation. In this endeavor, we compare the set of variables for the pre-directive period (until 2016) with the post-directive periods (2018 onwards). This approach is consistent with prior works that have also revised the effects of NFRD implementation (e.g., [9,10]). This method was used in prior studies to consider the improvement of the quality or quantity of sustainability disclosures (including environmental ones). In our work, we modify the comparisons accordingly, to shed some light on the possible symptoms of environmental decoupling (under the assumption that quality disclosures reflect “talk”, while hard quantitative ones—the “real actions”).

Our exploratory study uses a sample of Polish listed firms, which is motivated by a few observations. First of all, Poland offers a unique experimental setting for this kind of research due to its relatively short history of sustainability reporting and the anxieties over the successful implementation of the NFRD [35,36,37]. These anxieties were omnipresent, although Polish listed firms have issued voluntarily sustainability reports since the implementation of RespectIndex by the Warsaw Stock Exchange in 2009. Therefore, among the EU peripheral countries, Poland remains the only one that offers a relatively large sample for sound investigations. Thus, the relative homogeneity of the sample, given the historical and legislative cross-country differences, is maintained. As pointed out by Orsato et al. [38], the ESG-related studies targeted at emerging markets (markets with less mature economies) are relatively scarce. On the other hand, according to Garcia et al. [39] there is a greater demand for ESG practices in emerging markets in comparison to mature ones. In this regard, our study offers a relevant contribution to the existing debate on firm’s environmental behavior by offering a comprehensive and in-depth study of Polish listed firms from diverse angles. Finally, following Klimczak et al. [34] observations, there is a potential arena for environmental decoupling among Polish listed firms, which we wish to verify.

Our work is based on the data available from the LSEG Eikon database (formerly known as Refinitiv Eikon DataStream) [40], looking at the firm’s environmental performance in two major aspects. The first is a firm’s energy efficiency, which is the indication of the use of energy as a resource. The second is carbon emissions that reflect the firm’s response to the climate neutrality targets. In a methodical context, for both aspects, we employ a set of variables that are informative in the context of a firm’s “talk” (qualitative disclosures based on firms’ declarations) and real actions (the measurable KPIs). We present these variables in Table 1, together with their definitions.

Table 1.

Tested variables and their definitions.

To cover the aspect of firms’ “talk” (stemming from qualitative disclosures and declarations), we test three variables (see Table 1). The first two variables reflect the score assigned to a firm regarding the carbon emissions (Em) or use of resources (Res), including the use of energy. These two scores are a part of the Environmental rating, within the overall ESG rating, provided by LSEG Eikon. The third variable we employ in the context of firms’ “talk” is a self-computed composite index that reflects the overall score based on the firm’s declarations on policies and targets related to energy use and emissions (P&T).

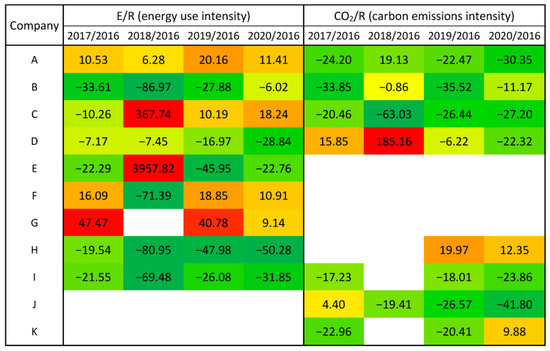

To cover the aspects of firms’ real actions, we employed two KPI-type intensity ratios provided by LSEG Eikon: energy use intensity (E/R) and carbon emissions intensity (CO2/R). Due to copyright issues and a need to maintain firms’ anonymity, we do not disclose disaggregated data for each company.

For the analysis of the data, we applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as it is suitable for the comparisons of paired data that are not normally distributed. We applied a Wilcoxon test to verify whether the changes in the variables of our interest (Table 1) were statistically significant, over the years, at a given company level. We perform this analysis for all Polish listed firms, available in LSEG Eikon, as of July 2022, for the period 2014–2020. As can be seen in Table 2, the number of Polish firms included in the LSEG Eikon database was constantly increasing, starting from 2014 as the first year of our observations. However, there is a visible discrepancy between the number of firms for which LSEG Eikon provided Em, Res, and values for P&T composite index, and the number of firms for which the data on real effects of emissions or energy efficiency are available.

Table 2.

Number of observations for indicators of our interest, as provided in LSEG Eikon.

Given the relatively low number of firms that provided their emission intensity score for 2016 (only eight), we supplemented our analysis with a firm-level study of the trends in real effects, based on the E/R and CO2/R, to support the conclusions on the possible areas for environmental decoupling among Polish listed firms.

4. Results and Discussion

The first stage of our analysis was to examine the changes in the variables of our interest (Em, Res, P&T, E/R, and CO2/R) over time. In Table 3, we report the year-to-year changes by providing p-values of the Wilcoxon test. We also provide changes in the mean values that inform whether the indicators have increased or decreased over time (as the dynamic indices). This analysis helps to detect whether firms have been improving their talk and real actions before the mandatory reporting regime (NFRD), as well as whether their talk and actions were improving continuously, not only in the year of NFRD implementation.

Table 3.

Indicators that reflect a firm’s environmental performance over time.

Data provided in Table 3 indicate that the implementation of the NFRD regulation had an impact on firms’ environmental disclosures at a qualitative level. The emission scores (Em) and resource use scores (Res) had changed at statistically significant levels (increase) between 2018 and 2019, as well as between 2019 and 2020. There was also a significant increase between 2017 and 2016, which could explain the first response of firms to the announcements of the timeline of the implementation of the NFRD, as a foreseen regulation. Interestingly, 2018, as the first year when the NFRD regulation was in force, has not brought statistically significant changes compared to 2017. These observations provide strong evidence that the mandatory reporting regime (NFRD) has resulted in an increase in environmental concern at the level of the firm’s scores (Em, Res) and declarations on the implementation of policies and targets (P&T).

If we consider the real effects, reflected by the changes in energy efficiency intensity (E/R) and carbon emissions intensity (CO2/R) we observe no statistically significant changes. This observation supports our hypothesis that environmental performance has changed at the level of declarations (policies and targets, which reflect a “talk”) rather than at the level of real actions. It suggests that there could be a problem of environmental decoupling among Polish listed firms. In particular, the data confirms previous empirical evidence about Polish companies overestimating their CSR practices in their sustainability reports [41].

In Table 4, we provide the results of the analysis of the variables of our interest that have changed after the NFRD implementation (2018, 2019, and 2020), relative to 2016 as the pre-directive period. The data support prior observations, namely that the effects are strongly visible at the level of qualitative indicators, reflecting the overall declarations on emissions or use of resources, as well as composite score P&T. The actual effects remain statistically insignificant for energy efficiency. There is, however, a statistically significant decrease in carbon emissions intensity (at 5% for 2020 relative to 2016 and 1% for 2019 relative to 2016). This is a positive observation, suggesting that firms are focusing on their emissions reduction, which is in line with climate neutrality targets. It also suggests that the potential problem with environmental decoupling emerges in the fields of environmental performance other than carbon emissions.

Table 4.

Environmental performance indicators—comparison of pre-NFRD period (2016) with post-directive periods (2018, 2019, 2020).

To revise this observation more in-depth, we supplement our analysis with the analysis of firm-level dynamic indicators of the studied KPIs, namely the energy use intensity (E/R) and carbon emissions intensity (CO2/R). Based on the LSEG Eikon database, we present below the heat map that reflects the positive and negative changes of these ratios over time. As we intend to capture the potential impact of the mandatory reporting regime (NFRD), for the firm-level analysis, we have chosen those companies that provided data on their energy use intensity and emissions intensity for 2016 (which we treat as pre-NFRD period). Then, we compared post-NFRD figures for 2018–2020 with 2016 by computing dynamic indices. Therefore, in the heat map (Figure 1), we graphically visualize the dynamics indices for 11 firms (named with letters to maintain anonymity) as case studies. As can be seen, a relatively larger number of firms provided complete data on their energy use intensity compared to emissions intensity.

Figure 1.

Heat map—changes in the energy use intensity (E/R) and carbon emissions intensity (CO2/R) at firm-level (base dynamic indices). Notes: The table presents the base dynamic indices (2016 as the base year) in percentage for E/R and CO2/R, in percentage. Colors follow a traffic-light system and range from green to indicate significant improvement (a drop of −50% or more), via yellow (dynamics around 0%, no significant change), to red to denote significant increase (an increase of 50% or more). Letters from A–K denote particular companies studied companies (cases). Source: Own study.

In the heat map presented in Figure 1, we adopted the traffic-light color system to distinguish between those firms that are the leaders of change (green) and those that are still increasing their emissions or use of energy (red). As can be seen, there are still cases with a significant increase in the use of energy (E/R) compared to 2016 levels. Overall, looking at the heat map, we observe that within the use of energy, all colors cover the heat map (with a relative balance between green improvement, yellow-orange stabilization, and red for worsening). There are firms that continuously improve their energy intensity (e.g., H, I, B, or D), as well as those that are far from real improvements (A, C, G, or F). However, as far as emissions are concerned (CO2/R), the majority of firms improved their real performance. There is only one firm with a significant increase in emissions intensity (case D, 2018/2016) and one firm that remains in the orange zone (H). Overall, within the carbon emissions intensity, there is a visible prevalence of decreases and related improvement (green). It confirms our former observation (based on the Wilcoxon test) that firms tend to be more focused on emission reductions, compared to other areas of environmental behavior.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have looked backward and revised whether the regulatory regime has positively impacted firms’ environmental behavior. More precisely, we have focused on detecting symptoms of environmental decoupling stemming from the difference between what firms disclose (“talk”) and implement in real activities. We employed the methodology used in prior works and compared the effects of the NFRD regulation in the 2016–2020 time span. Our findings suggest that Polish firms could be affected by an environmental decoupling strategy of overestimating their environmental performance by increasing qualitative disclosures. We find that there were significant improvements in qualitative disclosures, e.g., firm’s environmental scores (resource and emissions scores, or policy scores), while target disclosures were not followed by improvement of KPIs indicators (energy use intensity and carbon emissions intensity).

Interestingly, our evidence documents only a real effect on CO2 emissions, which suggests that environmental decoupling has potentially emerged in those fields of environmental performance that are given less attention by policymakers. The evidence of significant improvement in qualitative disclosures is in line with legitimacy theory [12,13], as well as suggests the existence of impression management [20]. Our empirical investigation confirmed that the effect of regulation was visible only in terms of declarations (policies, targets, as the proxies of “talk”), therefore helping firms to legitimize their performance by declarations disclosed to stakeholders.

Our study contributes to the extant literature in two main ways. First, it adds a sound methodology to detect environmental decoupling in reporting practices based on the triangulation of different information. Instead of building on a single multidimensional ESG Eikon score, we focus on ad hoc environmental scores and on manually collected information. Indeed, LSEG Eikon ESG scores combine different granular information about environmental disclosure and real performance, mixing them in one single measure. Differently, we focus on narrowed environmental scores and compare them with the related KPIs indicators of real performance. This approach allowed us to detect potential problems of environmental decoupling within the environmental aspects other than emissions. This result is aligned with the current policymakers’ focus on carbon emission reporting because, recently, a lot of regulations and guidelines (e.g., Fit for 55 [42]) have been introduced to enhance the measurement and management of emissions to mitigate climate risks. Also, at the analytical level, numerous works adopted only carbon emissions as a hallmark of green behavior and environmental concern. Therefore, we complement this literature with other facets of a firm’s environmental performance.

A second relevant contribution is concerned with the practical implications of this analysis. Our evidence confirms the criticism raised by the NFRD regulation, which is mainly related to its flexibility in scope and reporting standards. In this regard, our evidence about environmental decoupling supports the current EU reporting system (the CSRD), which has introduced a rigid taxonomy to define ex-ante the scope of sustainability reporting and the assurance of disclosure by third parties to avoid the risk of overestimating organizations’ contribution to sustainable development.

Our study has several limitations. The first is that the research process was narrowing the research sample to Polish companies. However, we performed the analysis for all Polish listed firms available in LSEG Eikon, as of July 2022, for the period 2014–2020. Therefore, the results are reliable for Poland. In addition, Polish companies were the only representatives of the Central and Eastern European Countries in LSEG Eikon database, which provides a valuable insight into European peripheral countries facing particular challenges of decarbonization. The second limitation is the illusive nature of the environmental decoupling, as it is challenging to detect if a scale counts. However, we applied sound methodology, driven by prior studies and it helped us to detect the potential symptoms within the environmental aspects other than emissions. It is not surprising to find emissions at the forefront because, recently, this aspect has been given a lot of attention, placing this aspect (emissions) as a central point of firms’ climate actions caused by direct interlinks. Also, at the analytical level, numerous works adopted only carbon emissions as a hallmark of green behavior and environmental concern. Thus, emissions are given a kind of priority as a proxy for environmental behavior.

In sum, this exploratory analysis provides the basis for more advanced studies aimed at understanding the antecedents and the consequences of environmental decoupling. Future research, for instance, could consider investigating whether and how different environmental topics may be the subject of impression management strategies or can apply a similar methodical approach to compare environmental decoupling across different countries and industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.-K. and M.P.; methodology, M.W.-K. and M.P.; software, M.W.-K.; validation, M.P.; formal analysis, M.P., A.L., A.S. and M.W.-K.; investigation, A.L. and A.S.; resources, M.P.; data curation, A.L. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.-K.; writing—review and editing, M.P. and A.L.; visualization, M.W.-K.; supervision, M.W.-K.; project administration, M.W.-K.; funding acquisition, M.W.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Economics in Katowice, grant “Beyond Barriers” number 02/BB/01/2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the insightful comments provided by the Reviewers of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022, Amending Regulation (eu) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Directive (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 Supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Sustainability Reporting Standards. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R2772 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Tashman, P.; Marano, V.; Kostova, T. Walking the walk or talking the talk? Corporate social responsibility decoupling in emerging market multinationals. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpur, S.; Nadeem, M.; Roberts, H. Corporate social responsibility decoupling: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2023. ahead-of-print. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367077934_Corporate_social_responsibility_decoupling_a_systematic_literature_review_and_future_research_agenda#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 3 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bothello, J.; Ioannou, I.; Porumb, V.-A.; Zengin-Karaibrahimoglu, Y. CSR decoupling within business groups and the risk of perceived greenwashing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.A.; Nadeem, M.; Zalata, A.M. Walking the talk? A corporate governance perspective on Corporate Social Responsibility decoupling. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 34, 2186–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2014/95/EU (2014) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0095 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Mio, C.; Fasan, M.; Marcon, C.; Panfilo, S. The predictive ability of legitimacy and agency theory after the implementation of the EU directive on non-financial information. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordazzo, M.; Bini, L.; Marzo, G. Does the EU Directive on non-financial information influence the value relevance of ESG disclosure? Italian evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3470–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, M.; Carrassi, M.; Muserra, A.L.; Wieczorek-Kosmala, M. The impact of the EU non-financial information directive on environmental disclosure: Evidence from Italian environmentally sensitive industries. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M.; Llena, F.; Carrasco, F.; Correa, C. Accountability and accounting regulation: The case of the Spanish environmental disclosure standard. Eur. Account. Rev. 2002, 11, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llena, F.; Moneva, J.M.; Hernandez, B. Environmental disclosures and compulsory accounting standards: The case of Spanish annual reports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Owen, D.; Adams, C. Accounting and Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social Environmental Reporting; Prentice-Hall: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. Quality of sustainability reports and impression management: A stakeholders perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, M.; Sabelfeld, S.; Blomkvist, M.; Dumay, J. Rebuilding trust: Sustainability and non-financial reporting and the European Union regulation. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. The transparency trap: Non-financial disclosure and the responsibility of business to respect human rights. Am. Bus. Law J. 2019, 56, 5–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Guidry, R.P.; Hageman, A.M.; Patten, D.M. Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Smid, H. Decoupling among CSR policies, programs, and impacts: An empirical study. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Montiel, I. When Are Corporate Environmental Policies a Form of Greenwashing? Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 377–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Ioannou, I. Mind the gap: The interplay between external and internal actions in the case of corporate social responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2569–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Lyon, T.P. Greenwash vs. brown wash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organ. Sci. 2014, 26, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchiello, A.F.; Marrazza, F.; Perdichizzi, S. Non-financial disclosure regulation and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: The case of EU and US firms. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Sealy, R.; Trojanowski, G. Understanding Research Findings and Evidence on Corporate Reporting: An Independent Literature Review; The Financial Reporting Council: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Adoption of SCR and Sustainability Reporting Standards: Economic Analysis and Review. NEBER Working Papers, Working Paper 26169. 2019. Available online: www.nber.org/papers/w26169 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Aluchna, M.; Roszkowska-Menkes, M.; Kamiński, B. From talk to action: The effects of the non-financial reporting directive on ESG performance. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Bianchi Martini, S.; Corvino, A.; Mazzoni, M. Voluntary versus mandatory non-financial disclosure EU directive 95/2014 and sustainability reporting practices based on empirical evidence from Italy. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, K.M.; Hadro, D.; Meyer, M. Executive communication with stakeholders on sustainability: The case of Poland. Account. Eur. 2023, 20, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, M.; Dyduch, J.; Gușe, R.; Krasodomska, J. Corporate Reporting Practices in Poland and Romania—An Ex-ante Study to the New Non-financial Reporting European Directive. Account. Eur. 2017, 14, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylec, A. Non-Financial reporting in Poland—Standards and first experience of companies related to the implementation of the Directive 201/95/EU. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. 2020, 144, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak, Ł.; Różańska, E. CSR Disclosure in Polish-Listed Companies in the Light of Directive 2014/95/EU Requirements: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J.; Garcia, A.S.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Simonetti, R.; Monzoni, M. Sustainability indexes: Why join in? A study of the ‘Corporate Sustainability Index (ISE)’ in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSEG Eikon Database. Available online: https://www.lseg.com/en/data-analytics/sustainable-finance/esg-scores (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Pizzi, S.; Principale, S.; Fasiello, R.; Imperiale, F. The institutionalisation of social and environmental accounting practices in Europe. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2022, 24, 816–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fit for 55 Package under the European Green Deal. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/package-fit-for-55 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).