Abstract

In 2022, under the combined influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic downturn. The employment landscape is grim, particularly for rural migrant workers, who are under immense pressure to secure employment. This study used structural equation modeling and bootstrapping methods to identify the influencing factors of migrant workers’ willingness to return home during public health emergencies and the potential multiple causal relationships, based on 2879 questionnaires on the employment status of migrant workers who are from Chongqing in 2022. The result of this study will be used as a reference by policymakers to formulate employment policies. The results show that: (1) Public health emergencies have no discernible direct impact on people’s willingness to return home. However, they have a significant positive effect on hometown belongings and a significant negative effect on income level and employment stability. These effects are ranked in order of influence: sense of belonging to hometown > income level > employment stability. (2) The willingness to return home is significantly impacted negatively by employment stability and income level, but it is significantly positively impacted by hometown belonging, with employment stability having the biggest impact. (3) There is a substantial inverse relation between income level and sense of belonging to hometown; the higher the income level, the stronger the capacity to withstand outside threats, and the greater the propensity to remain employed. (4) Three pathways exist by which public health emergencies affect migrant workers’ willingness to return home: “PHE→ES→HI”, “PHE→IL→HI”, and “PHE→ES→IL→HI”. (5) Income level and employment stability have multiple chain’mediating effects between public health emergencies and the willingness to return home, while only income level plays a partial mediating role between employment stability and the willingness to return hometown.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak at the end of 2019 had a significant influence on the global social economy [1], food security [2], anti-poverty efforts, and physical health [3]. The vast spectrum of infections and the extraordinarily rapid spread of COVID-19 complicated the prevention and management of public health emergencies. Several countries (e.g., the U.S., Sweden, Brazil) implemented a “no resistance” policy, avoiding quarantine and city-closure measures, leading to massive COVID-19 outbreaks, high mortality rates, and severe impacts on the health and daily life of local residents. Some countries (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, and Vietnam) adopted the “0-COVID-19” approach (i.e., the elimination strategy) [4]. The preventive and control measures severely restricted the production and transportation, leading to frequent enterprise shutdowns. Tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs, experienced significant wage declines, and fell into poverty crisis [5]. The International Labor Organization (ILO) emphasized that the labor market was severely affected in 2020, with an 8.8% reduction in total hours worked, equivalent to the loss of 255 million full-time jobs, highlighting the significant impact of COVID-19 on employment and the workforce [6]. Although China implemented effective measures to quickly contain the spread of COVID-19, the pandemic still seriously impacted Chinese socio-economic development [7], especially in labor-intensive industries and tourism, where the unemployment rate was significantly higher [8]. Data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics show that the urban survey unemployment rate increased from 5.2% at the end of 2020 to 5.5% at the end of 2022. Although the labor force size increased, the proportion of migrant workers (laborers with rural household registration who work in cities other than the district or county in which their household registration is located, and who at the time of the study were still at their workplaces and had not returned to their hometowns) decreased from 59.38% to 58.15%. The epidemic posed a significant challenge to migrant worker employment, highlighting unemployment issues and increasing the trend of returning to hometowns.

Rural–urban migration has consistently been a research hotspot in geography, sociology, and economics. Numerous studies have primarily focused on the laws and influencing factors of migration, laying a theoretical foundation and helping researchers better understand the complex process of population migration [9]. Neoclassical economic theory posits that the wage gap between immigrants and local residents, along with future income expectations, are key factors in migration [10]. Push–pull theory suggests that rural labor migration results from the mutual influence and interaction between the “push” factors of the origin and the “pull” factors of the destination. Ravenstein’s laws of step migration propose that people first migrate from villages to small towns, from small towns to cities, and from cities to the metropolis, and each main current of migration produces a compensating counter-current [11]. Subsequent research by scholars has confirmed the existence of the law of migration [12,13], and some scholars have expanded the law of migration in response to new features of population migration. During the current postindustrialized age, economic, and social forces seem to be impelling some groups of people to move downward within the national urban hierarchy [14,15]. The new economic migration theory differs from traditional theory by emphasizing the family as the decision-making unit, prioritizing the maximization of expected income and minimization of risk for the family when deciding on outward movement or migration [16]. The classical theoretical model has significantly impacted academic research. Subsequent researchers have continuously improved and expanded these theories on the basis of reference theories, enriching the research perspective on labor migration [17]. Rural labor migration and mobility are common phenomena, reducing labor waste and improving the production efficiency of the agricultural sector to some extent [18,19]. The driving factors of labor force transfer are inextricably linked with the individual labor force and their families, the natural environment of rural areas, and sociolect–economic development [20]. Individual factors significantly impact rural labor force transfer [21,22]. Although the direction of the factors’ role varies, gender [23], quality of the non-agricultural labor force [24], education level [25], health status [26], and others significantly affect rural labor force transfer. Additionally, the family plays a decisive role in transfer decision-making, with the maximization of family income being a significant factor [27]. Higher incomes in the place of migration are an important factor in the outmigration of rural labor [28]. If the locality lacks better resources or employment opportunities, families often choose to transfer outward to fully utilize their labor force [29].

However, environment changes alter the original push–pull structural relationship between regions, subsequently affecting the outward or return migration of the rural labor force. For both foreign immigrants and domestic migrants, individual characteristics, economic factors, and social connections with their hometowns influence the decision to return home. Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, scholars have examined the impact of this public health emergency on labor transfers. On the one hand, COVID-19 has altered the livelihood status of migrant workers, increased the risk of livelihood vulnerability [30], and placed low-income families in a difficult situation, thereby enhancing their willingness to return home.

On the other hand, employment stability [31], lack of employment opportunities [32], social discrimination [33], income level [34], and a sense of belonging to home [35] significantly impact the willingness to return home. Existing research addresses the causes, influencing factors, and individual differences in labor force transfer from a multi-scale perspective across different geographic regions, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of public health emergencies on labor force transfer. However, current research predominantly focuses on the positive flow of the labor force from rural to urban areas and less developed regions to developed regions, with limited studies on the reverse flow of migrant workers. Meanwhile, factors influencing the labor force return primarily focus on individual and family characteristics, while the impact of the regional and macro environments and their complex interconnections remain clear. The impact of public health emergencies on labor migration is significant, and COVID-19, the worst outbreak in a decade, is a good indicator of the impact of public health emergencies on the willingness of the labor force to return home. In light of this, this study uses the COVID-19 epidemic as a case to examine the impact of public health emergencies on migrant workers’ willingness to return home, aiming to quantitatively analyze the multiple causal relationships and identify key influencing factors that drive migrant workers to their homes.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The research area is Chongqing, China, a municipality located in the southwest of China’s inland and the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. Statistics show that by the end of 2022, the total number of rural migrant workers amounted to 7.51 million, which is a typical labor exporting province, of which 5.09 million people were outbound laborers, a decrease of 0.9% compared with that of the previous year, mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic and the socio-economic downturn, so it is typical and representative to take Chongqing Municipality as the study area. In view of the lack of systematicness of the existing data on the transfer of rural labor force and the difficulty of conducting a census, this study, supported by a team survey project, conducted a questionnaire survey on the “impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the willingness to return home” from 23 April to 30 April 2022, with the migrant labor force in Chongqing municipality (who are currently outside but have not returned home) as the research object, and conducted a questionnaire survey on the “impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the willingness to return home” by field surveys and telephone interviews. Two investigators were assigned to one survey group, and semi-structured interviews were conducted, with each questionnaire taking about 30 min. A total of 3000 questionnaires were distributed in this survey, and 2879 valid questionnaires were collected. The recovery rate was 95.97%, which meets the statistical requirements.

The basic information statistics of the questionnaire survey samples are shown in Table 1. Males accounted for 82.60%, and females accounted for 17.40%. The age distribution of most samples is between 46–60 years old, accounting for 41.50%, followed by 26 to 35 years old accounting for 25%; the educational level of the sample is generally low; junior high school education accounted for 28.10%, primary school and below accounted for 33.80%, and only 4.7% of the education in college and above; in terms of health status, most of the samples are relatively healthy or very healthy, accounting for 31%; 32.50% were in general health status; and 8.30% of the samples are unhealthy.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the sample.

In order to guarantee the study’s scientific validity, the common method bias test takes about preventing the impact of a single sample source on the rise or fall in inter-dimensional correlations. According to the suggestions of PODSAKOFF [36] and other scholars, referring to the relevant experience of Zhang Anmin [37] and other scholars, the factor analysis of 27 topics was conducted by the Harman single factor test. Five factors with eigenvalues larger than 1 were extracted by rotating principal component analysis, and the cumulative explained variance was 79.72%. The explained variance of factor 1 was 30.88%, which was less than 50%. Therefore, there was no serious common method variation in the data in this study. The study’s measurement items’ absolute values of skewness and kurtosis coefficients fall within the standard range, as per Kline’s proposed standard [38]. This suggests that the data on each measurement item approximates a normal distribution.

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Theoretical Analysis

Since entering the 21st century, China has experienced two major public health emergencies: the SARS epidemic and the COVID-19 epidemic. These epidemics have caused economic contractions and capital transfers, altering the supply and demand dynamics in the labor market. As a result, the working hours, income levels, and livelihood strategies of migrant workers have been affected, accelerating their return to their hometowns. According to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data-simulation study, 70% of migrant workers’ wages decreased to varying degrees during the epidemic [34]. After the outbreak, 7.1% of non-poor households believed they might fall into poverty, and 23% of households that had escaped poverty felt at risk of returning to poverty [39]. A social survey conducted among youth in India found that one-third of respondents who had paid jobs before the lockdown were unemployed afterward, and 50% of those working outside their state returned home [31]. A survey from Central Vietnam during the COVID-19 epidemic revealed that all households were at high risk of livelihood vulnerability, with less educated, less socially connected, and younger workers being the most [30]. The epidemic has made the living and working environments of migrant workers uncertain, with a high possibility of health damage. Social and cultural differences between inflow and outflow areas also create significant physical and psychological stress for migrant workers [40]. Based on this analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a:

Public health emergencies significantly and positively affect the willingness to return home.

H1b:

Public health emergencies significantly and negatively affect income levels.

H1c:

Public health emergencies significantly and negatively affect employment stability.

H1d:

Public health emergencies positively affect the sense of belonging to the hometown.

The return of laborers to their hometowns is influenced by multiple factors, especially during public health emergencies, which greatly impact the urban employment market. Increased living costs, social and cultural differences, and low employment stability in cities push migrant workers to return to their homes. The reduction in employment opportunities leads to heightened economic pressure, forcing urban laborers to seek economic support or re-employment in their hometown [41]. Factors such as income levels, number of working days per week, percentage of remittance income, and whether migrant families have jobs significantly relate to the willingness to return home [42]. Reduced working hours and job losses result in declining wages, particularly for temporary workers, low-income groups, and employees of small and micro enterprises [43]. Additionally, the living environment and familial connections in their hometowns make migrant workers more willing to return home. Empirical data from Tanzania show that unstable jobs for male laborers and failed marriages for females are the primary reasons for returning home [44]. Migrant workers facing high discrimination [33], support pressure, and lack of urban housing [45] are more inclined to return home. Non-agricultural employment significantly contributes to household income. Research in ethnic areas indicates a substantial income gap between agricultural and non-farm labor, with non-farm employment significantly boosting income levels [46]. Other critical factors include the presence of left-behind family members [47], land resources [48,49], and the age of the labor force [50]. Based on the urban “push” and the rural “pull”, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a:

Employment stability significantly and negatively affects the willingness to return home.

H2b:

Income level significantly and negatively affects the willingness to return home.

H2c:

The sense of belonging to the hometown significantly and positively affects the willingness to return home.

H3a:

Employment stability significantly and positively affects income level.

H3b:

Employment stability significantly and negatively affects the sense of belonging to the hometown.

H3c:

Income level significantly and negatively affects the sense of belonging to the hometown.

Public health emergencies universally impact society, especially affecting migrant workers’ income levels, psychological pressure, working hours, and living security. These emergencies reduce income levels and employment stability, prompting migrant workers to consider returning home. In contrast, the countryside can still provide a self-sufficient material base, allowing laborers to earn through flexible employment, thus strengthening their willingness to return home. The sense of belonging to hometown becomes more and more prominent under the stress of an epidemic. The migrant workers experience great psychological pressure during the epidemic, and the sense of belonging positively influences their willingness to return home. At the same time, public health emergencies affect the stability of employment and income levels. For example, during the COVID-19 epidemic, because of the suspension of large-scale sports activities, a large number of part-time or seasonal workers engaged in sports activities have been severely challenged [51]. The employment environment directly led to a decrease in income, and the reduction in employment opportunities and income levels affected the emergence of the willingness to return home. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a:

Employment stability mediates the relationship between public health emergencies and willingness to return home.

H4b:

Income level meditates the relationship between public health emergencies and willingness to return home.

H4c:

The sense of belonging to hometown meditates the relationship between public health emergencies and willingness to return home.

H4d:

Employment stability and income level has a serial meditating effect on the relationship between public health emergencies and willingness to return home.

H4e:

Income level meditates the relationship between employment stability and willingness to return home.

H4f:

The sense of belonging to hometown meditates the relationship between employment stability and willingness to return home.

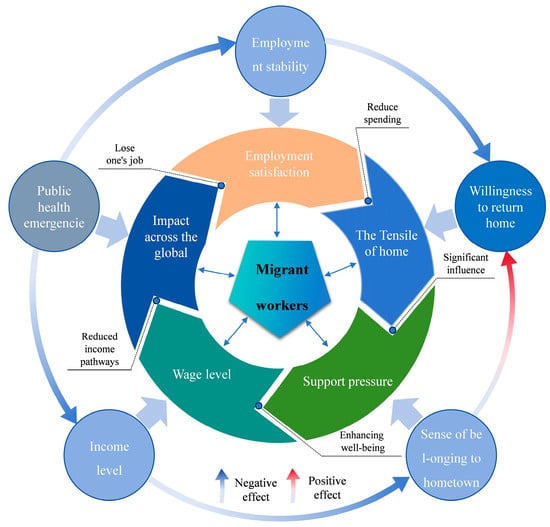

Based on existing research, this paper constructs a theoretical model of the willingness of migrant workers to return home through theoretical analysis (Figure 1). The model contains six latent variables: public health emergencies are the forward variables, employment stability, income level, and sense of belonging to hometown are mediating variables, and willingness to return home is the result variable. The global spread of public health emergencies impacts the employment stability, income level, and sense of belonging to hometown of migrant workers, reflected in employment satisfaction, wage level, and family support pressure. The interplay of various factors affects the emergence of the willingness to return to their hometown.

Figure 1.

Model diagram of willingness to return home.

2.2.2. Structural Equation Model

In order to clarify the causal relationship between public health emergencies and the willingness of laborers to return home, this study adopts the structural equation model (SEM), a multivariate statistical analysis method proposed by Joreskog and Wiley in the 1970s that combines factor analysis and path analysis to identify and verify causal relationships. Its advantage is that it can better verify the stochastic relationship between variables compared with other multivariate statistical methods [52]. In the context of multiple mediating and latent variables hypothesized in this study, the SEM method can well estimate the direct [53] and indirect effects [54] between them, as well as the estimation error and model fitting [55]. In SEM, some variables can be dependent in some equations and independent in others; existing research has used SEM models to address influence mechanisms and path analysis of each [56,57,58]. Therefore, this study adopts the SEM model to analyze the influencing factors of migrant workers’ willingness to return to their homes. In the empirical test, the SEM model is constructed as follows:

Equations (1) and (2) are measurement models used to describe the linear relationship between latent variables and observable variables, where the factor loadings with the indicator variables (X, Y), ξ, and η are exogenous latent variables and endogenous latent variables, respectively, and δ and ε are measurement errors. Equation (3) is a structural equation describing the linear relationship between latent variables, where β is the relationship between endogenous latent variables, Γ is the influence of exogenous latent variables on endogenous latent variables, and ζ is the residual. There are five exogenous potential variables in this paper, which are public health emergencies, employment stability, income level, sense of belonging to hometown, and willingness to return home, corresponding to 27 observed variables (PHB1-PHB5, SOB1-SOB6, ES1-ES6, IL1-IL4, HI1-HI5) and residual e1–e29.

2.3. Variable Selection

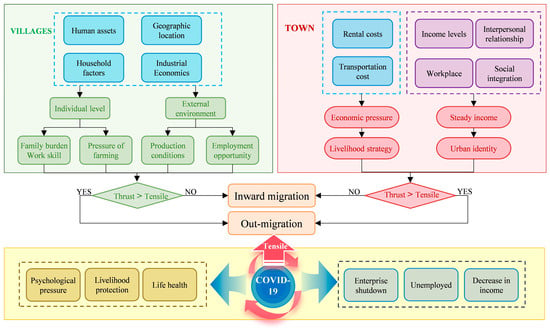

American demographer Donald Borg put forward the theory of push and pull of rural labor force transfer in the late 1950s, pointing out that the transfer of rural labor force is the result of the interaction between the “push” of the transfer-out place and the “pull” of the transfer-in place. According to the Todaro migration model [59], as long as there is an income gap between urban and rural areas, the labor force will continue to shift to non-agricultural areas, making agricultural production income decrease and non-agricultural production income increase [60]. The backwardness of rural conditions and fewer employment opportunities, coupled with the lack of employment skills and the pressure of support for rural laborers have prompted the labor force to shift outward in order to increase family income. On the contrary, the improvement of external conditions and the increase in income level will attract the labor force to return home. Higher income levels and good employment opportunities in urban areas attract rural labor inflows, but the impact of public health emergencies, the costs of living in cities, cultural identity, and other factors will also become the thrust for the outflow of laborers. With the change in external environmental conditions, the push–pull structure of urban and rural areas will also change, and the labor force will show a dynamic transfer between cities and rural areas (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analytical framework of labor transfer based on push–pull theory.

Based on the analysis of the push–pull theory, the scale design includes two parts: the first part is the demographic characteristics of the sample subjects, and the second part is the measurement question items for the main variables in the model. In order to ensure the reliability and validity of the research sample, the measurement questions in the model are derived from existing studies at home and abroad [21,22,61], and the formulation is improved by considering the actual situation of migrant workers in Chongqing. The measurement questions were all based on the Likert five-level scale (Table 2), with 1 indicating “strong disagree” and 5 indicating “strong agreement”. Five first-level variables were set: public health emergencies, employment stability, income level, sense of belonging to hometown, and willingness to return home. On the issue of index setting, the differences in the cognitive ability of the questionnaire survey objects were fully considered, and the content of the questionnaire was designed to meet the measurement of each indicator, as far as possible, to fit the lives of farmers and eliminate obstacles to understanding.

Table 2.

Model variables and their descriptions.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Structural Equation Model Estimation and Test Results

The reliability and validity of the scales were measured using SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 28.0 software. The Cronbach’s values for all five dimensions were greater than the standard value of 0.7, indicating that the internal consistency of the measurement topics within a single dimension was better [62]; the values of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were greater than the standard values of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, indicating the good convergent validity of this model (Table 3). According to the suggestion of Fordell [63] and other scholars, the open square value of AVE for each of the constructs in this study is greater than the correlation coefficient between the remaining constructs, so the constructs have better discriminant validity between them (Table 4).

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity of the research model.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

The model’s goodness of fit indicators was examined using AMOS 28.0 software. When is between 0 and 3, it indicates the model suitability is better; when the similarity index (GFI, IFI, TLI, CFI) is greater than 0.9 and closer to 1, the better the fitness between the data and the model; when the difference index (RMSEA) is less than 0.08, the model has good goodness of fit. = 4.810, RMSEA = 0.045, GFI = 0.963, IFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.982, and CFI = 0.985, which all meet the model’fit requirements. Therefore, the sample model has good goodness of fit, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key indicators for model fitting.

3.2. Model Hypotheses Test

3.2.1. Direct Hypothesis Testing

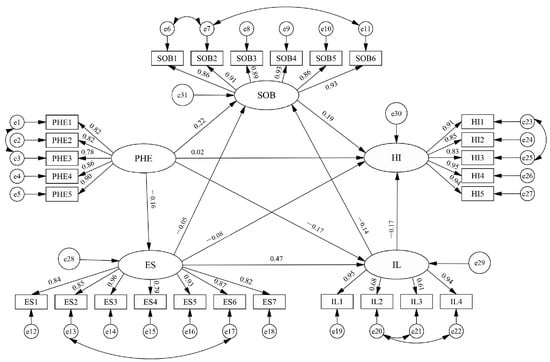

According to the results of Table 6 and Figure 3, the standardized coefficients of H1b, H1c, H1d, H2a, H2b, H2c, H3a, and H3c are −0.169, −0.16, 0.221, −0.082, −0.17, 0.194, 0.466, and −0.143, respectively, and p < 0.001, which passes the hypothesis test, and the hypothesis is valid. The standardized coefficients of H1a and H3b are 0.018 and −0.052, p > 0.001, respectively, which did not pass the hypothesis test, and the hypothesis was not established. Public health emergencies do not have a direct effect on the willingness to return home, but they have a significant effect on the income level, employment stability, and sense of belonging to hometown. The degree of influence is the sense of belonging to hometown > income level > employment stability, among which the sense of belonging to hometown has the greatest impact, with a path coefficient of 0.256. According to the hypothesis test results, from the perspective of rural households, due to the reasons of left-behind elderly and children, cultural identity, and hometown development, the COVID-19 epidemic makes migrant workers psychologically consider more about the survival of the family, which strengthens the sense of hometown belonging of migrant workers (e.g., in the samples of those who have the intention to return to their hometown, the average number of left-behind children and the elderly is 1.5 and 1.7, respectively). In addition, the impact of public health emergencies on employment stability and income level is also significant, with path coefficients of −0.188 and −0.193, respectively, which is mainly due to the fact that the occurrence of public health emergencies leads to the stoppage of enterprises and production, and the migrant workers face layoffs and frequent changes of jobs. (Of the 2879 samples researched by field investigation, 26.26% said that they had changed their jobs three times or more in the past 3 years.) During the normal production period, most factories adopt a 12 h or 8 h rotation operation, and the income of employees can also be maintained at a stable level. Since the outbreak of the epidemic, some enterprises have stopped work and production or have taken a day of work and a day of rest to reduce their costs. Employees are also often affected by the sealing and control of the epidemic from time to time, resulting in a significant decline in the stability and income level of migrant workers and even the existence of the phenomenon of salary arrears, and the income level has dropped significantly (40.19% of the 2879 samples surveyed by field investigation indicated that there had been arrears in wages, and 36.89% indicated that the wage level was lower than before the epidemic).

Table 6.

Model path analysis and hypothesis testing results.

Figure 3.

Results of structural equation modeling of willingness to return home (Analytical framework of labor transfer based on push–pull theory. Annotation: Numbers represent path coefficients; circles (e1–e29) represent residuals).

Employment stability has a significant positive impact on income level and a significant negative impact on the willingness to return home, where the path coefficient of income level is 0.452, which means that a decrease of 1 unit in employment stability is followed by a decrease of 0.452 units in income level. Work stoppage, layoffs, skill level, job satisfaction, etc., reflect the stability of employment, and the stability of work affects the income level; the income level has a significant negative impact on the willingness to return home and the sense of belonging to the hometown. The higher the income level of migrant workers, the higher the sense of urban identity, the more positive the future employment expectation, and the more willing they are to stay in the city. The sense of belonging to hometown has a significant positive impact on the willingness to return home. Due to the employment opportunities in the hometown, the left-behind elderly and children, and the development of the hometown, the willingness to return home is strong.

3.2.2. Mediation Effect Test

The results of the hypothesis testing above found that public health emergencies do not directly lead to the willingness to return home. In order to further verify the complex process of the willingness to return home, this study adopts the bootstrapping method to test the mediating effect between public health emergencies and the willingness to return home. Referring to the suggestion of Hayes [64], the bootstrap sample size is set to 2000, and the confidence level is set to 95%. According to the results of the mediating effect test (Table 7), the total effect between public health emergencies and the willingness to return home is 0.077, and the mediating effects of employment stability and income level are significant (the confidence interval does not include 0, Z > 1.96). The ratios of the two dimensions to the total effect are 16.88% and 37.66%, respectively, and the multiple mediating effects are transmitted level by level through employment stability and income level, and the mediating effect value is 0.013, accounting for 16.88% of the total mediating effect. Among them, the mediating path “public health emergencies→employment stability→willingness to return home”, “public health emergencies→income level→willingness to return home”, “public health emergencies→employment stability→income level→willingness to return home” path has a significant indirect effect. Therefore, it can be concluded that employment stability and income level have a significant mediating effect of the influence of public health emergencies on the willingness to return home, and Hypotheses H4a, H4b, and H4d are valid. There is no mediating effect of the sense of belonging to hometown on the impact of public health emergencies on the willingness to return home, and Hypothesis H4c is not valid.

Table 7.

Mediated effects results.

Similarly, the results of the mediating effect between employment stability and willingness to return show that at the 95% confidence level, the confidence interval of the Bias-Corrected method and the confidence interval of the Percentile method do not contain 0, and that the total effect is significant, the indirect effect and the direct effect are significant, and the employment stability and the willingness to return are partially mediated. Specifically, the effect value of the path “employment stability→income level→willingness to return home” is −0.079, accounting for 50% of the total mediating effect. However, the two path effects of “employment stability→sense of belonging to hometown→willingness to return home” and “employment stability→income level→sense of belonging to hometown→willingness to return home” are not significant (the confidence interval includes 0, Z < 1.96). Therefore, it can be concluded that income level has a significant mediating effect on the impact of employment stability on the willingness to return home, assuming that Hypothesis H4e is valid; the sense of belonging to hometown has no mediating effect in the influence of employment stability on the willingness to return home, and Hypothesis H4f is not valid.

In the mediating effect of public health emergencies and willingness to return home, employment stability and income level play a mediating role, mainly through three paths to have an impact. First, public health emergencies lead to reduced employment stability, thereby increasing the willingness to return home. (Among the samples with a strong willingness to return home by field investigated, 30.6% said that they had changed their jobs more than three times in the past 3 years, 69.71% had moderate or lower job satisfaction, 66.5% were in the risk zone, and 67.39% had anxiety because of the epidemic.) Furthermore, public health emergencies directly lead to a reduction in the level of income and enhance willingness to return home (among the samples with a strong willingness to return home by field investigated, 53.17% of the monthly wage level is below CNY 3000, and 42.39% say that the wage is lower than before the epidemic; in the sample in the risk zone, the average monthly wage level is about CNY 2500, 44.27% of which indicates that there is an unpaid wage). Third, public health emergencies have an impact on employment stability, which in turn is reflected in the change in income level, resulting in the emergence of the willingness to return home. Migrant workers cannot afford the cost of renting rooms and conducting their lives in the city and tend to return home to reduce the conducting of their lives in order to offset the impact of the decline in income.

The sense of belonging to the hometown directly affects the willingness to return home and does not play an intermediary role. In the direct-effect test, public health emergencies have a significant positive effect on the sense of belonging to hometown, and the sense of belonging to the hometown also has a significant positive effect on the willingness to return home. In the mediating-effect test, several paths through the sense of belonging to hometown are characterized by non-significance, indicating that the sense of belonging to hometown does not play a mediating role in the impact of public health emergencies and employment stability on the willingness to return home, but the sense of belonging to hometown directly affects the willingness and intention to return home. The possible reason for this is that whether it is during the epidemic or not, the improvement of the sense of belonging to hometown will promote the willingness to return home, while the occurrence of public health emergencies has increased the sense of belonging to hometown of migrant workers, but under the control of epidemics and considering the cost of transportation, migrant workers will not immediately plan to return home. Another reason is that public health emergencies have an impact on the sense of belonging to their hometown, but because migrant workers have jobs and interpersonal relationships, they do not immediately have the willingness to return home, and they will tend to return home only after employment and income are severely affected.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms Influencing Willingness to Return Home

The traditional push–pull theory identifies the push and pull factors of origin and destination areas, but it lacks an analysis of the multiple complex causalities in the migration process. This study found that migrant workers do not immediately take measures to return home after being affected by public health emergencies, aligning with the findings of other scholars [61,65]. On the other hand, although public health emergencies significantly enhance the sense of belonging to the hometown, they do not significantly increase the willingness to return home, suggesting a potential lag in the epidemic. There are three primary reasons for this lag:

First, public health emergencies have a pervasive impact on society, with all regions implementing measures to prevent and control outbreaks. The Chinese government has adopted a “dynamic zeroing” prevention and control policy, categorizing regions into low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk zones based on the epidemic’s severity. Individuals in high-risk zones are restricted from leaving, and those who have traveled to high-risk zones within the last 14 days must undergo a lengthy period of isolation before resuming their activities. Due to the risk of infection during the journey home, the costs of transportation and time, and the uncertainty of the epidemic situation in their hometown, migrant workers often choose to observe for a period before deciding whether to return home based on the change in the epidemic situation. Thus, the impact of the epidemic on migrant workers’ return decisions is not immediate but exhibits a certain lag.

Additionally, stable employment is the primary factor influencing migrant workers’ decisions regarding their willingness to return home. Continuous income growth is the primary goal of migrant workers, and stable jobs facilitate the achievement of this goal. Among the interviewees with a low willingness to return home, most indicated that despite being in high-incidence areas, enterprises guaranteed their basic livelihoods through online offices and employment subsidies. However, interviewees engaged in construction, manufacturing, and flexible employment industries said that low welfare benefits and employment security(34.6%, 30%, and 17.1% in the three industries, respectively, and 19.3% in other industries), which were severely impacted by the epidemic, leading to work stoppages and unemployment (41.4%, 28.2%, and 8.1% in the three industries that were out of service for more than 45 days, and other industries accounted for 22.3%), thereby obstructing income acquisition. Interviewees with a strong willingness to return are often concentrated in these industries.

Lastly, population flow and migration in China, a country that values social networks and interpersonal relationships, demonstrate the typical spatial proximity effect of origin and destination. Origin and destination models also show that the amount of population migration is correlated with both the size of the population and the distance between origin and destination [66], indicating that the relationship between pushing and pulling forces alone is not sufficient to directly encourage migration. Due to “geo-relationships” between the migrant workers and the surrounding areas, as well as the distance between the workplace and their hometowns, migrant workers may not take immediate action to return to their hometowns following the occurrence of a public health emergency, even when the origin place’s pull force is larger than the push force and the destination place’s pull force is bigger than the pull force. Nevertheless, since the places of origin and destination of the interviewees in this study are dispersed, so the spatial proximity effect was not analyzed in depth, related research needs to be further explored.

4.2. Policy Implication

The impact of COVID-19 on society may be a medium- and long-term process that accelerates the return of migrant workers to their hometowns. With the wealth and work experience accumulated from working elsewhere, returnees may choose to seek local employment, start a business, or work outside again. However, the government needs to consider resettlement measures for returnees who return home due to poor health, older age, and other reasons. In particular, public health emergencies may lead to a large-scale “wave of returnees”. This influx can increase the employment pressure on the local labor force, potentially affecting social stability. The development of employment-stabilization policies and measures plays an important role in improving the sustainability of the employment of the labor force and in guaranteeing a sustainable increase in the income of the labor force, which in turn promotes the sustainable development of the countryside. Therefore, it is necessary for government departments to introduce corresponding policies and measures. However, the labor market and government intervention differ significantly across countries. Developed countries have relatively complete employment security systems and labor market norms, which may not be applicable to the conditions of developing countries. Therefore, based on empirical analysis, this paper puts forward the following policy suggestions for developing countries on how to stabilize employment for labor force sin the context of public health emergencies:

- Actively introducing employment stability policies. This study finds that public health emergencies do not directly cause a willingness to return home; rather, employment stability directly influences both income level and the willingness to return home. During the epidemic, restrictions on the movement of people, regional lockdowns, and enterprise closures had severe impacts on migrant workers. Local governments should actively implement burden-reduction policies for enterprises and provide employment subsidies, policy counseling, job recommendations, and other forms of assistance to enhance the employment stability of migrant workers.

- Pay attention to the psychological state of migrant workers. Due to the occurrence of public health emergencies and the consideration of the cost of living in the city, coupled with the influence of the risk of physical health and the elderly and children left behind in the hometown, migrant workers are under psychological pressure in many aspects. The local government should provide psychological counseling channels and health education and publicity, advocate for all sectors of society to be concerned about and support migrant workers, and strengthen the supervision of enterprises’ employment behavior to prevent enterprises from taking advantage of the epidemic to maliciously default on wages or layoff employees, so as to further reduce the economic pressure and psychological burden of migrant workers.

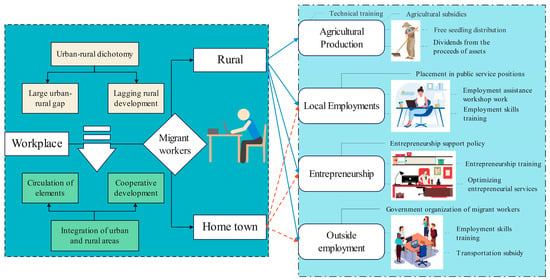

- Promoting the integrated development of urban and rural, and improving measures for the resettlement of people returning to their hometowns. The integrated development of urban and rural areas is crucial for addressing major social contradictions. At the institutional level, policies and measures to promote rural development should be actively introduced. The rural revitalization strategy is an important measure to advance rural development and achieve modernization of agricultural and rural areas. The return of migrant workers injects new vitality into rural revitalization. For those returning to rural areas to engage in agricultural production, risks should be mitigated by providing agricultural production subsidies, asset-income distribution, and skill training. Promoting local employment for returnees can be realized through vocational skills training, public service posts, placement in employment assistance workshops, and other measures. For those wishing to start their own business, necessary policy and financial support should be provided to create a conducive entrepreneurial environment. Additionally, returnees should be encouraged to re-enter the workforce. Government departments should facilitate job introductions, provide transportation subsidies, and offer employment skills training to enhance the employability of migrant workers (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Employment support mechanism for returnees.

Figure 4. Employment support mechanism for returnees.

4.3. Contribution and Limitations

The contributions and characteristics of this study are as follows: Primarily, this study adopts a novel perspective distinct from the traditional push–pull theory by reversing the urban push and rural pull dynamics and attempts to compensate the inadequacy about push–pull theories on the problem of reverse flow. This approach reveals the influencing factors on the willingness of migrant workers to return home during public health emergencies and examines the multiple mediating effects of employment stability and income level, whereby it enriches the research perspective on labor transfer. Furthermore, this study explores the potential mechanisms through which public health emergencies impact the willingness of migrant workers to return home to China and proposes corresponding countermeasures and suggestions. These findings aim to inform the formulation of employment assistance policies for migrant workers in similar developing countries. However, during the field research, it was observed that specific factors such as the purchase of houses in urban areas by migrant workers and their employment insurance also significantly influence their decision-making regarding the willingness to return home. Future research should study deeper into the impact of these specific elements on the willingness of migrant workers to return home, enhance long-term tracking of the samples, investigate the lagged effects of public health emergencies on employment, and compare further the differences in the return process between different regions.

5. Conclusions

This study is based on the push–pull theory and adopts the structural equation model to identify the impact of public health emergencies on the willingness of migrant workers to return home and their multiple causal relationships. (1) Public health emergencies have no discernible direct impact on people’s willingness to return home. However, they have a significant positive effect on hometown belonging and a significant negative effect on income level and employment stability. These effects are ranked in order of influence: a sense of belonging to the hometown > income level > employment stability. (2) The willingness to return home is significantly impacted negatively by employment stability and income level, but it is significantly positively impacted by hometown belonging, with employment stability having the biggest impact. (3) There is a substantial inverse relation between income level and sense of belonging to hometown; the higher the income level, the stronger the capacity to withstand outside threats and the greater the propensity to remain employed. (4) Three pathways exist by which public health emergencies affect migrant workers’ willingness to return home: “PHE→ES→HI”, “PHE→IL→HI”, and “PHE→ES→IL→HI”. (5) Income level and employment stability have multiple chain-mediating effects between public health emergencies and the willingness to return home, while only income level plays a partial mediating role between employment stability and the willingness to return home.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.X., T.L. and H.L.; methodology, C.X. and T.L.; software, C.X.; validation, C.X. and T.L.; formal analysis, C.X.; investigation, C.X., X.C. and T.Z.; resources, C.X. and X.C.; data curation, C.X. and T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.X. and T.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.X. and T.L.; visualization, C.X. and X.C.; supervision, C.X. and H.L.; project administration, C.X. and T.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Innovation Research 2035 Pilot Plan of Southwest University (WUPilotPlan031); Special Fund for the Youth Team of Southwest University (SWU-XJPY202307); Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No.20XJCZH005); The postgraduate research innovation project of Southwest University ‘Study on the Impact of Public Health Emergencies on the Willingness of Migrant Workers to Return Home’ (SWUS23075).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Leaders of Chongqing Rural Revitalization Bureau and the project group led by Heping Liao for providing the data and the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank. The Global Economy: On Trach for Strong But Uneven Growth as COVID-19 Still Weighs. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/06/08/the-global-economy-on-track-for-strong-but-uneven-growth-as-Covid-19-still-weighs (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Onyango, E.O.; Owusu, B.; Crush, J.S. COVID-19 and Urban Food Security in Ghana during the Third Wave. Land 2023, 12, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.T.; Duong, D.M.; Pham, T.Q.; Mirzoev, T.; Bui, A.T.M.; La, Q.N. COVID-19 Stressors on Migrant Workers in Vietnam: Cumulative Risk Consideration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Patrick, A.; Miquel, O.B.; Bary, P. Aiming for Zero COVID-19 to Ensure Economic Growth. 2021. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/aiming-zero-covid-19-ensure-economic-growth (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- WHO. Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Livelihoods, Their Health and Our Food Systems. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people%27s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- International Labour Organization. COVID-19 and the World of Work, 7th ed.; International Labour Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Global Economic Prospect: Pandemic, Recession: The Global Economy in Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/502991591631723294/global-economic-prospects-june-2020 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Liu, K. COVID-19 and the Chinese economy: Impacts, policy responses, and implications. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2021, 35, 308–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Massey, D.S. Return migration by German guest workers: Neoclassical versus new economic theories. Int. Migr. 2002, 40, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Laws of Migration. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1885, 48, 167–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, W. Migration: Ravenstein, thornthwaite, and beyond. Urban Geogr. 1995, 16, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, F. The migration patterns of two northamptonshire villages: Whiston and Strixton 1851 to 1891. Fam. Community Hist. 2024, 27, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plane, D.A.; Henrie, C.J.; Perry, M.J. Migration up and down the urban hierarchy and across the life course. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15313–15318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mai, X.; Zhang, L. Patterns of onwards migration within the urban hierarchy of China: Who moves up and who moves down? Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 2436–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O. Research on rural-to-urban migration in LDCs: The confusion frontier and why we should pause to rethink afresh. World Dev. 1982, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaji’c, S.; Vinogradova, A. Overshooting the savings target: Temporary migration, investment in housing and development. World Dev. 2015, 65, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. The impact of agricultural labor migration on the Urban–Rural dual economic structure: The case of Liaoning province, China. Land 2023, 12, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Chen, F.; Ouyang, X. The Impact of Changes in Rural Family Structure on Agricultural Productivity and Efficiency: Evidence from Rice Farmers in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. A Empirical Study of Rural Labor Migration for Anti-poverty Effect Have Based on the Survey from Farmers of Gansu Province. Popul. J. 2017, 39, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Employment, emerging labor markets, and the role of education in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2002, 13, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Lina, S. Chinese peasant choices: Migration, rural industry or farming. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2003, 31, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, D. “Push” versus “Pull” factors in migration outflows and returns: Determinants of migration status and spell duration among China’s rural population. J. Dev. Stud. 1999, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, X. The impact of family capital on farmers’ participation in farmland transfer: Evidence from rural China. Land 2021, 10, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yan, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J. Effect of rotation fallow on labor transfer: A case study in three provinces of Hebei, Gansu and Yunnan. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 2348–2362. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Qiao, J.; Xiang, D.; Peng, T.; Kong, F. Can labor transfer reduce poverty? Evidence from a rural area in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y. The group characteristics and macro background analysis of China’s rural labor mobility at the present stage. Chin. Econ. 1997, 6, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewska, G.; Markowski, L. Determinants of the Tendency for Migration of Nursing Students Living in Rural Areas of Eastern Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Geography of Rural Households; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, L.T.H.; Bond, J.; Ty, P.H.; Phuong, L.T.H. The Impacts of COVID-19 on Returned Migrants’ Livelihood Vulnerability in the Central Coastal Region of Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, B.; Bhatiya, A.Y.; Imbert, C.; Lohnert, M.; Panda, P.; Rathelot, R. Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on India’s rural youth: Evidence from a panel survey and an experiment. World Dev. 2023, 168, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R.B.; Phillips, J. “Mad dogs and transnational migrants?” Bajan-Brit second-generation migrants and accusations of madness. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2006, 96, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, W.; Zhang, C.; Xie, Y.; Lv, J.; Ahmad, S.; Cui, Z. The impact of social exclusion and identity on migrant workers’ willingness to return to their hometown: Micro-empirical evidence from rural China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Diao, X.; Chen, K.Z.; Robinson, S.; Yu, Y. The Impacts of COVID-19 on Migrants, Remittances, and Poverty in China: A Microsimulation Analysis. China World Econ. 2021, 29, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazli, K.; Bowman, C.; O’Leary, M. Race and Immigration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian National Park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhao, L. Influence of perceived value on the willingness of residents to participate in the construction of a tourism town: Taking Zhejiang Moganshan tourism town as an example. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.-F.; Liu, C.F.; Gao, J.-J.; Wang, T.; Zhi, H.; Shi, P.; Huang, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural poverty and policy responses in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2946–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Yang, Y.; Man, S. Regional Differences and Influencing Factors of Urban Migrants’ Psychological Integration in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.E.B. The Economic Well-Beig of Movers and Stayers: Assimilation, Impacts, Links and Proximity. In Proceedings of the Conference on African Migration in Comparative Perspective, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4–7 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Girimallika, B. Distress migration and involuntary return during pandemic in Assam: Characteristics and determinants. Indian J. Labour Econ. 2002, 65, 801–820. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Fa, Y.; Hu, B.; Cui, Q. The aggregate and Structural Impacts of Public Health Event on Employment and Wage. Financ. Trade Econ. 2021, 42, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kalle, H.; LilleØr, H.B. Going Back Home: Internal Return Migration in Rural Tanzania. World Dev. 2015, 70, 186–202. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, L.; Yuan, L.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, Y. How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. The Influence of Human Capital Accumulation and Outgoing Employment onthe Income of Rural Residents in Ethnic Areas: An Empirical Study Based on 2013–2015 Survey in Ethnic Areas of China. Ethno-Natl. Stud. 2018, 3, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.Y. Employment choice of rural return migrants around the Pearl River Delta region and its influencing factors. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 2305–2317. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Shi, W. Determinants and Effects of Return Migrant in China. Popul. Res. 2017, 41, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Liao, H.; Sun, P.; Shi, M.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. Characteristics of Labor Transfer of Poverty-stricken Families and Response Strategies for Rural Revitalization in Southwest Mountainous Areas. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Su, Q.; Sheng, N. The research on rural labor transfer employment space-time path: A case study of four sample villages in Anhui province. Geogr. Res. 2014, 33, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Sheptak, R.D.; Menaker, B.E. When Sport Event Work Stopped: Exposure of Sport Event Labor Precarity by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2020, 13, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Ma, B.; Sun, B.; Wen, Y. Effect of forestry ecological projects on poverty alleviation in Wuling mountainous areas: A structural equation model analysis. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 31, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- McEachan, R.R.C.; Sutton, S.; Myers, L. Mediation of personality influences on physical activity within the theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, K.; Zewotir, T.; Ndanguza, D. A combined model of child malnutrition and morbidity in Ethiopia using structural equation models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo-Vazquez, D.; Herrador-Alcaide, T.C.; Matin, A. Circular economy orientation from corporate social responsibility: A view based on structural equation modeling and a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Xue, Y. Decision-Making Mechanism of Farmers in Land Transfer Processes Based on Sustainable Livelihood Analysis Framework: A Study in Rural China. Land 2024, 13, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandyari, H.; Choobchian, S.; Momenpour, Y.; Azadi, H. Sustainable rural development in Northwest Iran: Proposing a wellness-based tourism pattern using a structural equation modeling approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; Mccarry, R. Behavioural drivers of long-term land leasing adoption: Application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.R.; Todaro, M.P. Migration, unemployment and development a two-sector analysis. Am. Econ. Rev. 1970, 60, 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Hao, J.I.; Min, L.I. Impact of non-agricultural employment on household income—Case study in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River basin. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; He, Q.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, L. Rural return migration in the post COVID-19 China: Incentives and barriers. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 107, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 66, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencutek, Z.S. Voluntary and forced return migration under a pandemic crisis. In Migration and Pandemic: Spaces of Solidarity and Spaces of Exception; Triandafyllidou, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.P.; Pace, R.K. Spatial econometric modeling of origin-destination flows. J. Reg. Sci. 2008, 48, 941–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).