Abstract

The Game Theory is aiding global tourism research to leverage destination appeal and competitiveness in the context of climate change advocacy. As global tourism continues to play a vital role in economic development and cultural exchange, there is a growing need to unravel the complexities of tourist behavior and destination competitiveness. Therefore, this study aims to utilize the Game Theory to investigate the relationships between Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness (RTDC), Tourist Visit Intention (TVI), and Destination Loyalty (DL) within the UAE, with the moderating role of Climate Advocacy. An online survey (using Google Forms) was distributed via social media platforms (primarily Facebook groups), resulting in data collection from 296 respondents. Smart PLS 4 and SPSS were utilized for data analysis. The findings revealed that RTDC had significant positive relationships with FOMO, DL, and TVI, thus supporting hypotheses 1 to 10. However, the hypothesis regarding Climate Advocacy moderating DL and TVI was not supported. Based on the Game Theory, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of regenerative tourism destination competitiveness and offers practical implications for destination management strategies. Limitations include reliance on self-reported data and context-specific considerations. Future studies should also consider cultural contexts, to enhance the external validity of research outcomes.

1. Introduction

The Game Theory has recently emerged as a modeling technique to identify optimal strategies and interactions across regenerative tourism stakeholders to maximize mutual benefits and long-term sustainability at host destinations [1,2,3]. In the present era, tourism is more popular than in previous decades, with many developed countries striving to attract more tourists to host unique tourism experiences [1]. Likewise, the UAE is being explored not only by domestic tourists but also largely by travelers from around the world. Many international tourists visit the UAE to explore its rich and diverse culture, which showcases a unique blend of ancient traditions and modern influences [2]. UAE has rapidly gained popularity due to its stunning landscapes, rich heritage, iconic innovations, and magnificent attractions (e.g., Palm Jumeirah and Burj Khalifa) [3]. Hence, this study aimed to explore the significance of tourist destinations (in particular, the UAE) by paying much attention to attractions of local and international tourists, by strengthening sustainability measures for protection against climate change, as well as by enhancing the destination popularity and enabling the destination to be globally competitive [4]. Globally, it is crucial to become more competitive in the tourism sector, especially as both developed and developing countries are increasingly focused on enhancing the appeal of their tourist destinations. This growing attention has inspired many researchers to explore this topic further [5]. Several elements are playing vital roles in the growth of destinations, including natural resources (such as air quality and carbon management), robust infrastructure, hidden cultural heritage, high-quality services at inns and resorts, and effective promotional activities [6].

Fear of Missing Out reflects the curiosity of travelers to embark on journeys that explore nature, discover unique destinations, and experience hidden cultures and heritage across various countries. Tourists choose to visit these unique destinations based on their personal interests and the influence of others. FOMO is the feeling people experience when they see others visiting a particular destination to explore its culture, heritage, and attractions. If they are unable to join them, they may feel left out or excluded [7]. In the tourism setting, FOMO affects the attitudes, thoughts, and expectations of a tourist about a destination. They do not want to miss out on the popular destinations to visit; therefore, FOMO motivates them to visit these destinations to increase their experiences and discover different cultures [8]. To visit a particular place, many factors affect tourists’ decisions. FOMO plays a crucial role in these decisions, significantly influencing tourists’ choices to visit specific destinations in search of unique experiences and cultural exploration [9,10].

Destination loyalty refers to the relationship between a destination and a tourist [11]. Destination loyalty is crucial for maintaining destination competitiveness. It develops through tourists’ positive moments and experiences, their attachments to places, the emotions and feelings they associate with those places, and their overall satisfaction with the destination. These factors shape tourists’ loyalty to destinations and increase the likelihood of them returning to the destination [12]. Various factors influence destination loyalty, including satisfaction, perceived value, emotions or feelings, and the overall quality of experiences related to the destination [13]. Tourist visit intention refers to when someone creates a plan to visit a destination or place for exploration because they are energetic and motivated to explore the heritage and tourist spots [14]. It’s like uncovering hidden treasures on a map, driven by a desire for discovery. With the help of these emerging and crucial factors, tourism marketers and practitioners can establish policies and strategies to enhance destination competitiveness [15]. Well-organized and beautiful destinations significantly influence tourists’ intentions and perceptions about visiting. If a destination is attractive and well-organized with many benefits, tourists are more likely to visit. Moreover, most of the tourist sites are moving towards sustainability and focusing on sustainable policies. Hence, this research also explores how climate advocacy impacts these elements of tourism destinations. Tourists play a crucial role in promoting climate advocacy by supporting policies essential for environmental protection and sustainability at travel destinations. Their choices and behaviors can drive demand for eco-friendly practices and encourage destinations to adopt and uphold sustainable initiatives, thereby contributing to the preservation of natural resources and the overall health of the environment [16].

The present study aimed to utilize the Game Theory to observe the connections among RTDC, FOMO, DL, and TVI, with the moderating role of CA. These factors are essential for increasing the ratio of tourists at specific destinations. Additionally, in this research, FOMO works as a mediator between RTDC and DL, as well as between RTDC and TVI, specifically in tourist sites in the various regions of the UAE. In this context, very few studies are identified in the UAE that explore these variables collectively; there is a need for more research to improve tourists’ motivation destinations (including UAE). Some researchers have conducted studies individually on these topics in previous years, but in the UAE context, they have not studied the interplay among these factors [17,18]. In the UAE, to understand the factors regarding how touristic sites can maximize the attention of tourists to explore these destinations, more studies are needed to identify the relationship among these factors. Further research is needed to address these gaps. Additionally, FOMO has been studied in different contexts, like social media marketing, consumer behavior, customer loyalty, and other areas in previous studies [19,20], but in the area of tourism, FOMO has not been examined extensively. Hence, this study aimed to address the following research questions:

- Does Travel FOMO and RTDC influence DL?

- Does RTDC, Travel FOMO and DL influence TVI?

- Does Travel FOMO mediate the relationship between RTDC and DL?

- Does Travel FOMO mediate the relationship between RTDC and TVI?

- Does CA moderate the relationship between Travel FOMO, TVI and DL?

This study is anticipated to make several significant contributions to the field of tourism management and marketing. First, by elucidating the impact of RTDC on DL and TVI, it provides valuable insights into how regenerative practices can enhance a destination’s appeal and foster long-term tourist loyalty. Second, it addresses the psychological factor of Travel FOMO and its influence on DL and TVI, offering empirical evidence on how this emotional driver affects tourist decisions. Third, the study examines the role of CA as a moderator, highlighting how sustainability practices can influence the relationships between Travel FOMO, DL, and TVI, thereby emphasizing the importance of environmental considerations in global tourism. Fourth, the application of the Game Theory in this context presents a novel methodological approach, enriching the understanding of stakeholder interactions and strategic decision-making in tourism. Collectively, these contributions aim to provide actionable insights for tourism managers, marketers, and policymakers, helping them to craft more effective marketing and sustainability strategies to attract and retain international tourists.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

The Game Theory refers to the mathematical framework used for analyzing situations in which multiple agents (referred to as players) make decisions that are interdependent. In the context of regenerative tourism, this implies that the outcomes for each player (or tourism stakeholders, e.g., policymakers, tourists, and tour operators) depend not only on their own decisions but also on the decisions of others [1,2,5]. In the context of destination competitiveness through the lens of the Game Theory, destinations can be considered as players using strategies (e.g., marketing, sustainability initiatives, and unique attractions) to compete for tourists. Likewise, tourists experience travel FOMO (i.e., a state of anxiety) as they consider others to have more fulfilling travel experiences. Hence, the Game Theory provides a critical explanation for the tourist choices that are influenced by the perceived experiences of others [2,8]. Therefore, the Game Theory extends to the understanding of the state of equilibrium where travelers balance their preferences and avoid overcrowded destinations [5,12]. In the context of climate advocacy, the Game Theory guides the underlying interactions between policymakers, tourism businesses, and tourists (e.g., imposition of taxes on carbon emissions, and adopting green practices) [13,15,17]. In addition, the Game Theory also advances the identification of strategies (e.g., offering loyalty programs and/or improved tourism services to attract repeat visitors) that maximize destination loyalty [2,13]. Importantly, the Game Theory helps to predict the likelihood of tourists choosing to visit a destination (e.g., tourism destinations constantly compete to convert potential interest into actual visits), based on the actions of competing destinations [2,5,15].

Hence, the Game Theory has become pivotal in advancing regenerative tourism research that identifies opportunities for optimizing multi-stakeholder cooperation and sustainability for long-term destination benefits. In the area of tourism, strategic framework and valuable insights for understanding the interactions and decisions of tourists to visit a specific destination are offered by the Game Theory [2,4,5]. Researchers should try to use the Game Theory in their research to improve the competitiveness of destinations in tourism. Researchers and practitioners can evoke the interactions among tourists, destination managers, and stakeholders to identify how advantages can be built, and strategies and policies can be evolved and implemented for improving tourism and destination competitiveness by employing the Game Theory. This research is beneficial to make destinations competitive for management of destinations by providing insights into obligatory responsibilities and duties, whereas it also ensures sustainability and eco-friendliness. The Game Theory provided a framework for this current study, incorporating different elements such as RTDC, FOMO, DL, and TVI, with the moderating role of CA. Literature review of the Theory provides the foundation for the methodology of this study in the area of regenerative tourism.

2.2. Destination Loyalty

Tourism destination loyalty can be better predicted through the Game Theory to equally understand the behavior of tourists and service providers. For improving tourism, the competitiveness of destinations is very important. Tourism departments manage the attractive destinations and to the respective destination, it can help to improve the tourist’s loyalty and motivate tourists to visit again and again [21]. Ramesh and Jaunky [22] studied that loyalty can be increased by several elements, including tourist satisfaction, a positive image of the destination, and perceived value. There is a deep relationship between tourists and destinations because tourists have many happy memories associated with destinations. This emotional connection often motivates them to revisit the respective destination to relive their memories [23,24]. Moreover, destination loyalty is influenced by factors such as perceived security, service quality, and perceived authenticity [25,26]. Chen and Chen [25] in their study suggested that the most important component of maintaining visitor loyalty is belief in performance and perceived security. Many practitioners are focusing on advanced technology and the use of digital systems in their research to examine their role in destination loyalty. Social media and digital experiences, such as Twitter chats, travel lists, and online distribution, influence tourist behaviour and interactions on websites [27,28]. The history of tourism is paving the way for adventurous tourism by transforming traditional tourism and enhancing destination experiences [29]. For success and to stand out in the tourism competition, emerging destinations need to focus on creating unique experiences and implementing effective marketing methods that engage tourists and foster destination loyalty [30].

2.3. Tourist Visit Intention

An increasing number of tourism scholars are relying on the Game Theory to strategically model the decision-making process of tourists. The tourist visit intention indicates that tourists visit a particular destination as planned and expected, with the willingness to learn about and explore the destination [31]. Adam, et al. [32] explore that the two main factors attracting tourists to destinations are motivation and satisfaction. Whether tourists prefer to visit destinations to explore the culture of places and regions, seek entertainment, or experience emotional motivations, these factors play a major role in shaping demand for tourism [33]. Tourists’ satisfaction with their visit intentions and the perceived benefits they receive from destinations, as well as how they explore the places, strongly impact their decision to revisit the destination [25]. Tourist visit intention is greatly influenced by brand image components such as reliability, perceived security, the beauty of the destination, as well as the popularity of places [11,34].

Moreover, in the present era, with the internet and information technology being highly advanced, tourists are aided in making decisions for selecting destinations. Nowadays, tourists are posting their experiences and journeys on social media, which impacts their decision-making process for planning trips [35]. Tourism research is important for enhancing interest in tourism and for spreading motivation to tourists to visit destinations, thus promoting tourism [36]. To promote tourism and increase tourist interest in visiting destinations, decision-makers and policymakers need to manage the factors that influence tourist visit intentions. By addressing key motivational factors and choosing the best strategic direction, destinations can become more competitive in the tourism market [37].

2.4. Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness

Regenerative tourism destination competitiveness involves attracting tourists to the host destinations offering regenerative activities within a competitive landscape [38]. It also includes both tangible and intangible factors that increase interest in a destination and promote sustainability in tourism. Cronjé and du Plessis [5] Identified six key elements that are crucial for tourism success, including cultural heritage, natural resources, infrastructure, perceived good services, marketing strategies, and policies. Famous destinations with strong infrastructure and effective destination management are likely to succeed in the international tourism market. Buhalis, et al. [18] emphasized the importance of sustainable development and innovation that is essential to increasing competitiveness. Sustainable tourism practices, such as environmental protection and social development, are crucial for gaining competitive advantages as well as achieving sustainability. Tourism destination competitiveness is affected by factors including perceived safety, brand image, and the overall tourist experience [39,40]. A better destination image and tourist satisfaction contribute to enhanced destination competitiveness and popularity. Over the years, technology has not only changed the number of tourists but has also affected access to competition. Marketing technology processes, online identities, social media, and local platforms also help enhance competitiveness [41,42].

2.5. Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) is a feeling that people experience when they see others having fun and spending their vacations at tourist destinations while using social media [10]. FOMO has a significant impact on tourists’ desires and how they plan their trips during their vacations, per Wojcieszak-Zbierska [43]. Consequently, tourists plan to travel to destinations because they don’t want to miss out on memorable, unique, and cultural experiences. Social factors influenced by the Fear of Missing Out have led tourists to transition from traditional travel to organized and advanced travel, seeking more significant and personally interesting activities during their trips. A research by [44] focused on travel satisfaction and social media usage in the context of tourism. They found in the study that tourists experiencing FOMO may have their own needs, seek approval, and share their experiences on social media. Tourists’ attitudes related to FOMO during their travels to respective destinations influence their decisions regarding which destination to select for their tours and trips [45]. FOMO has a strong connection with tourists’ behaviours, which include choosing a destination, intention to revisit, and destination loyalty.

2.6. Climate Advocacy

The Game Theory is advancing the opportunities to devise effective strategies to encourage cooperation and drive positive change toward climate change and mitigation. Climate advocacy refers to efforts and actions aimed at promoting policies, behaviors, and initiatives (e.g., raising awareness, policy influence, community engagement, sustainable practices, and legal action) to address and mitigate the impacts of climate change [46,47]. Enhancing sustainability in tourism and mitigating the environmental impacts of tourism spots while protecting the environment is known as ecotourism [46]. In the present era, various scholars and practitioners are paying more attention to the topic of climate change because it is becoming a globally recognized issue. Kaján and Saarinen [47] stress the importance of collaboration among tourism firms, stakeholders, and governments in protecting and maintaining the environment; climate advocacy campaigns involve activities such as assisting workers in reducing waste at the workplace; constructing eco-friendly buildings; and implementing strategies and policies for carbon management. Gössling, et al. [48] argued that climate change contributes to competitive advantage by attracting environmentally conscious tourists and creating positive tourism qualities. Consequently, the moderating role of climate advocates influences the association between tourist behaviours and destination impacts. For example, someone who strongly believes that tourist spots should be healthy and clean is likely to return to destinations with responsible conservation and environmental protection activities [49]. Based on the above discussion, we may assume that climate advocacy can influence tourists’ preferences in visiting and choosing destinations for future trips.

2.7. Hypotheses Development

2.7.1. Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Destination Loyalty

Tourism destination competitiveness refers to how a destination can attract more tourists compared to other destinations [50]. Wong [51] argued that the accessibility and attractiveness of a destination, along with the benefits it offers, have a significant impact on tourists’ loyalty and potential. Destinations that stand out from the competition offer uniqueness, quality service, and a great location. This ensures good tourist relations and often leads to repeat visits [51,52]. Another important concept is perceived image and value, which play a crucial role in developing destination loyalty [53]. An interesting fact is that when a place or destination is competitive and can offer memorable and great experiences for tourists, it encourages them to revisit the same destination [53,54]. The Game Theory illustrates how collaborative strategies in regenerative tourism can enhance destination appeal, that can ultimately foster long-term visitor loyalty and competitive advantage [52,53,54]. Hence, based on the Game Theory, it can be concluded that higher tourism destination competitiveness will enhance tourists’ loyalty to the destination. Based on the above argument, the following hypotheses have been developed:

H1.

Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness has a positive and significant effect on Destination Loyalty.

2.7.2. Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Tourist Visit Intention

Tourism destination competitiveness includes the ability to attract and satisfy tourists compared to other destinations [50]. Destination competitiveness plays an important role in tourists’ visit decisions, per Mahdzar, et al. [55] Tourists who choose a competitive destination are generally believed to have a higher desire and motivation to visit [56]. Ultimately, the perceived value and image of a destination play important roles in promoting tourism [57]. Competition with other destinations leads to those that maintain safety, cleanliness, and good value generating more interest from tourists to visit [58,59]. The Game Theory clarifies how regenerative tourism enhances destination competitiveness, thus incentivizing tourists’ visits through mutual benefits and sustainable value creation [55,56,57]. Therefore, according to the Game Theory, destinations that succeed in these aspects will have a higher level of tourism competitiveness, which will encourage tourists to visit them. Based on the above argument, the following hypotheses have been developed:

H2.

Regenerative Tourism Destination has a positive and significant effect on Tourist Visit Intention.

2.7.3. Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

It is accepted that tourism destination competitiveness emphasizes environmental awareness and sustainable practices [60]. According to Higgins-Desbiolles [61], Nowadays, tourists are interested in natural and sustainable destinations, prioritizing innovation and environmental sustainability. A destination that focuses on nature conservation and environmental protection policies can make tourists feel special, but sometimes it can lead to feelings of self-doubt. Moreover, the impact of FOMO on tourists’ behaviour is influenced not only by value but also by other significant factors [45]. Competitive destinations appear to offer immersive experiences and new activities that increase FOMO behaviour among tourists [62]. The Game Theory explains how regenerative tourism’s competitiveness fosters travel FOMO by compelling travelers with unique and sustainable experiences they do not want to miss [60,61,62]. Therefore, based on the Game Theory, it is concluded that regenerative tourism destination competitiveness will be positively associated with travel FOMO.

H3.

Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness has a positive and significant effect on the Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO).

2.7.4. Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) and Destination Loyalty

Travel FOMO involves anxiety about missing out on a memorable experience or a good opportunity. In [63], researchers predicted a significant and positive association with destination loyalty. Research by Lee, et al. [63] demonstrates that tourists who experience FOMO during travel tend to make trips and are attracted to tourist spots offering exceptional and unique opportunities. Moreover, scholars have also explored FOMO in the context of tourists’ emotions and experiences, concluding that FOMO contributes to destination loyalty [64]. Tourists’ desires and motivations are very important to stay connected with their anticipated destinations. They feel grudged for missing out on any opportunity to visit their desired destination. Tourists wish to visit again and again their favourite destination because they have different memories connected with that place and want to relive those beautiful and happy moments again and again [65]. The Game Theory elucidates Travel FOMO’s impact on destination loyalty by analyzing competitive choices that influence tourists’ decisions and behaviors strategically [63,64,65]. Thus, based on the Game Theory, there is a significant relationship between Travel FOMO and Destination Loyalty.

H4.

Travel FOMO has a positive and significant effect on Destination Loyalty.

2.7.5. Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) and Tourist Visit Intention

Tourists don’t want to miss the opportunities to visit their favourite destinations, so they are inspired by FOMO’s factors. Furthermore, tourists are motivated to discover other destinations according to their interests and happiness [66]. Most tourists are very conscious about the opportunities to revisit their favourite tourist sites because they don’t want to miss them. They want to identify many other tourist sites to create happy and beautiful memories, and they are driven to visit them again and again to their desired destination due to their emotional attachment to that place to recollect memories [66]. The tourists are driven by the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) to be fascinated with desired and beautiful tourist sites as they are very conscious about the opportunities to revisit their favourite places in the context of tourism [63]. The Game Theory explains how travel FOMO influences tourist visit intentions by analyzing decision-making strategies in competitive tourism markets [63,64,65,66]. Based on the Game Theory, this study has established the following hypothesis:

H5.

Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) has a positive and significant effect on Tourist Visit Intention (TVI).

2.7.6. Destination Loyalty and Tourist Visit Intention

Destination loyalty states the tourist’s attachment towards desired destinations due to their memories connected with that place, which are formed during their momentous experiences at that place. These memories serve as a motivating factor, inspiring tourists to revisit destinations and reminisce about their past experiences [67]. Many tourists wish to revisit specific and desired destinations repeatedly because they feel connected to those particular destinations where they have spent their time [23,58]. Loyalty can be enhanced by offering more benefits and services at desired destinations, which in turn motivates tourists to revisit the same destination [68]. The Game Theory explains how destination loyalty affects tourist visit intention by analyzing the strategic choices and interactions among tourists and destinations [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Based on the Game Theory, it is concluded that Destination Loyalty positively influences Tourist Visit Intention. Therefore, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

H6.

Destination Loyalty (DL) has a positive and significant effect on Tourist Visit Intention (TVI).

2.7.7. Mediating Role of Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

The purpose of the present research is to examine the mediating role of FOMO between RTDC and DL, as well as its mediating role between RTDC and TVI. FOMO refers to the feeling of missing out when tourists see posts on social media about desired destinations, prompting them to visit those destinations to avoid missing out on making memories. Competitive destinations enhance tourists’ loyalty to destinations [69,70]. As a result, the mediation role of FOMO in the relationship between RTDC and DL is established. FOMO is projected to mediate the relationship between RTDC and TVI. Moreover, destinations’ competitiveness can encourage tourists to revisit their desired destination to collect happy memories [69,70]. Based on the Game Theory, this study stated the following hypothesis:

H7.

Travel FOMO mediates the relationship between RTDC and DL.

H8.

Travel FOMO mediates the relationship between RTDC and TVI.

2.7.8. Moderating Role of Climate Advocacy

In the area of tourism, climate advocacy is considered a main factor that raises awareness about climate change and reduces the fear of a polluted environment. It impacts the behaviour of tourists to support green environments and sustainability. With the help of these behaviours, tourists can activist policies and initiatives intended for environmental protection [71]. Most of the studies are conducted on the concern of the tourists regarding climate protection. As a result of these studies, it is identified that tourists may experience feelings of missing out on visiting opportunities, grow tourists’ loyalty towards the desired destinations, and increase intentions to visit favorite destinations. It is identified that these factors may affect various behaviours related to Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), destination loyalty, and support for the policies to protect the environment [72,73]. Therefore, sustainable behaviours that improve understanding of the loyalty of tourists to visit desired destinations are the primary objectives of “Climate Advocacy” and FOMO that are affected by the policies of environmental protection and sustainability in the tourism sector. Hence, taking reliance on the Game Theory, the following hypotheses are stated by this study:

H9.

CA moderates the relationship between FOMO and DL.

H10.

CA moderates the relationship between FOMO and TVI.

H11.

CA moderates the relationship between DL and TVI.

3. Methods

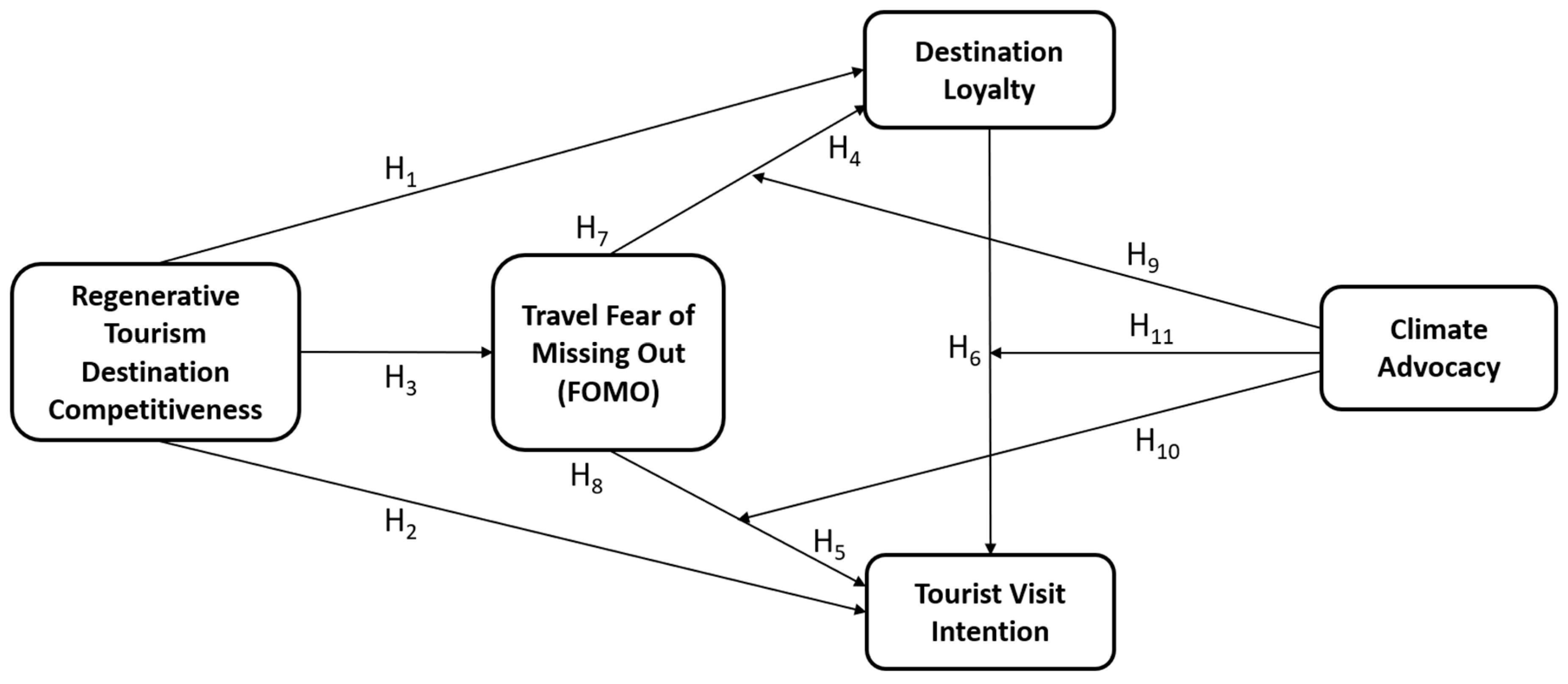

The primary goal of this research (within the Game Theory framework and the use of quantitative methods), is to examine the relationship between RTDC, FOMO, DL, and TVI with the moderation of CA in the tourism sector of the UAE (see Figure 1). The Game Theory uniquely contributes to understanding Travel FOMO, RTDC, TVI, and DL by modeling the strategic interactions among tourists and destinations. It explains how tourists’ travel decisions are influenced by their perceptions of others’ experiences (FOMO) and how destinations compete through strategies such as sustainability initiatives and unique offerings (RTDC). This framework predicts how these competitive strategies affect TVI and their likelihood to return (DL). Moreover, the Game Theory incorporates climate advocacy by examining how environmental policies and practices impact the behavior of stakeholders, thereby influencing overall destination competitiveness. This approach offers valuable insights into optimizing tourism strategies and advancing sustainable practices. This research employs a survey-based quantitive study design. The population for this study comprised both native and international tourists visiting the UAE. This broad population was chosen to capture a wide range of perspectives and experiences related to tourism in the UAE. Including both local and international tourists ensured a comprehensive understanding of how various factors—such as RTDC, FOMO, DL, TVI, and CA—affect different groups within the tourism sector. This diverse population provided a more holistic view of the tourism dynamics in the UAE and allowed for the examination of cross-cultural and cross-national variations in tourist behaviors and perceptions [43]. The sample size for this study was determined based on guidelines from Hair Jr, et al. [74], which recommend a sample size approximately 10 times the number of items in the questionnaire. With 32 items included, the target sample size was initially set at around 320 respondents. To further refine this estimate, additional sample size criteria from PLS-SEM guidelines were applied. Kock and Hadaya [75] suggested using the inverse square root method, which indicated a minimum sample size of 113, and the gamma-exponential method, which suggested a range of 150–200. Based on these criteria, the final sample size for the study was N = 296, which balanced practical data-collection constraints with the need for statistical reliability and validity.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Convenience sampling was employed as the sampling technique for this study. This non-probability sampling method was chosen due to its practical advantages in accessing and surveying a large number of respondents within the constraints of time and resources [2]. Convenience sampling allowed the researchers to efficiently gather data from readily available respondents, although it may introduce some biases related to the representativeness of the sample. For comparison purposes, we used scales established by previous researchers, as presented in Appendix A. The questionnaire explored multiple dimensions with 32 items as subscales sourced from prominent studies. Throughout the questionnaire-development process, a five-point Likert scale was employed, representing responses on a vertical scale using numbers 1–5 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) for concise questions. The data for this research consisted of the visitors and tourists within the UAE. Although the study included both domestic and international tourists, the data from these groups were not examined separately. Instead, the decision to group them together was based on the assumption that the constructs of interest (RTDC, FOMO, DL, TVI, and CA) would exhibit similar patterns across different tourist types. This assumption was grounded in the premise that the fundamental relationships between these constructs are likely to be consistent regardless of the tourist’s origin, given the universal nature of the constructs being studied. Data for the study was collected using a structured questionnaire administered through online surveys. This technique was selected due to its efficiency and ability to reach a broad audience, including both native and international tourists in the UAE. Online surveys facilitated the collection of data from a geographically dispersed sample, aligning with the study’s objective of capturing diverse tourist experiences and perceptions. To estimate and validate the hypothesized relationships using the final sample dataset (N = 296), this study utilized SmartPLS 4 and SPSS v26 software. Factual analysis was conducted using SPSS, while SmartPLS 4 was utilized to evaluate various inter-construct relations and examine the structural model.

4. Results

Data was analysed for completeness and accuracy using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 26 and SmartPLS version 4. SPSS was utilized to perform demographic tests and descriptive analysis. Furthermore, PLS-SEM was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships between variables. We opted for SmartPLS for several reasons. The study adopted variance-based Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) instead of covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) due to its suitability for exploring complex models with multiple constructs and interactions, as well as its flexibility with smaller sample sizes and non-normal data distributions. PLS-SEM emphasizes prediction and theory development, which aligns with the study’s objective of understanding the intricate relationships between RTDC, (FOMO), DL, and TVI, with CA as a moderator. Unlike CB-SEM, which requires larger sample sizes and strict data assumptions, PLS-SEM allows for robust analysis with the available sample size and effectively handles the model’s complexity and exploratory nature [74]. To statistically determine the possibility of common method bias, the present study employed the widely known Harman’s single factor (HSF) test [76,77]. The HSF test revealed that CMB was clearly non-existent as the total estimated variance (as explained by a single factor) was just 38.76% (i.e., much lower than the cutoff value of 50%) [76,77].

4.1. Demographic Test

This section contains demographic information about respondents, including gender and age, travel frequency, and number of hotel night of stay (Table 1). The age distribution shows a fairly even spread among different age groups, with the highest representation coming from individuals aged 25–34 years (24.7%). This suggests that this age group is notably active in tourism. The 45–54 age group also constitutes a significant portion (23.0%), highlighting substantial engagement from middle-aged travelers. Conversely, the younger group of 18–24 years (14.2%) and the older demographic of 55 and above (19.3%) are also well-represented, indicating a diverse age range among the respondents. Gender distribution is nearly balanced, with males comprising 50.3% and females 49.7%. This nearly equal representation ensures that the study’s findings are representative of the general tourist population without significant gender bias. In terms of travel frequency, most respondents travel 3–5 times per year (35.1%), reflecting a high level of engagement with travel. Additionally, 29.7% of participants travel 1–2 times per year, while fewer respondents travel 6–10 times (23.3%) or more than 10 times annually (11.8%), showcasing varied travel habits among the sample. Regarding the number of hotel nights, the majority of tourists stayed 4–7 nights (32.8%), suggesting a preference for moderate-length stays. A considerable portion also stayed 8–14 nights (28.7%), indicating a tendency for longer stays. Fewer respondents stayed 1–3 nights (24.3%) or more than 14 nights (14.2%), reflecting a range of stay durations. This diverse demographic profile provides a thorough understanding of the tourist population in the UAE, enhancing the reliability and applicability of the study’s results across different tourist segments.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Respondents.

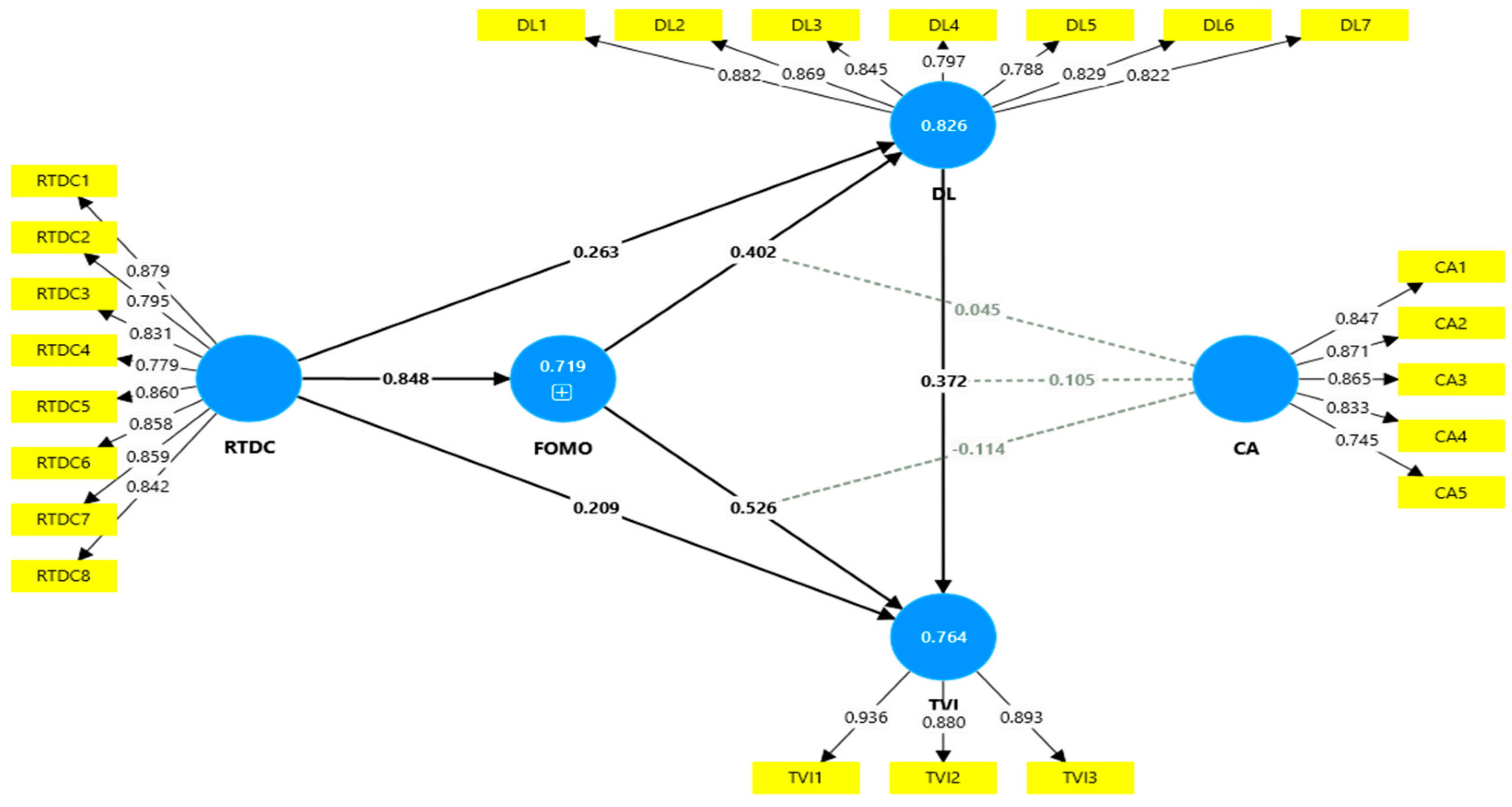

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model is evaluated to examine the quality of the constructs. The analysis of the quality criteria begins with the outer loadings, followed by the examination of construct reliability and validity (see Table 2). As shown in Figure 2, the measurement model also presents the coefficients (beta-value estimations) for all hypothesized relationships.

Table 2.

Loadings, CA, CR & AVE.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Measurement Model Estimations.

4.2.1. Factor Loadings

Factor or Outer Loadings is defined as “the extent to which each of the items in the correlation matrix correlates with given principle component” [78]. In this study, one item was found to have a value lower than 0.50, as suggested by [79]. As a result, CA6 was deleted in this study (see Table 2).

4.2.2. Analysis of Reliability

According to Mark [80], “Reliability is defined as the extent to which a measuring instrument is stable and consistent. The essence of reliability is repeatability. If an instrument is administered over and over again, will it yield the same results”. The findings of Composite Reliability ranged from 0.919 to 0.950, while “Cronbach’s Alpha” ranged from 0.887 to 0.939 (see Table 2). Both “Composite Reliability” and “Cronbach’s Alpha” indicate reliability values higher than the recommended threshold of 0.70 [81].

4.2.3. Convergent Validity

When the value of the Average Variance Extracted is equal to or greater than 0.50, it indicates that the underlying construct is measured through convergent items [82]. The results of convergent validity depend on the statistics of AVE. All variables have values higher than the recommended threshold, indicating that convergent validity is established. Results are summarized in Table 2.

4.2.4. Discriminant Validity—Fornell and Larcker Criterion

According to the Fornell and Larcker [82] criterion, discriminant validity is established when a construct’s AVE is greater than its correlation with other constructs. In the current study, the construct’s AVE was found to be higher than its correlation with another construct, providing strong support for discriminant validity. Results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

4.3. Structural Model

The next stage in SEM is to assess the proposed hypotheses by evaluating the hypothesized link.

4.3.1. Hypotheses Testing

Direct Relationship

H1 posits that RTDC has a positively significant effect on DL. The results show that RTDC has a significant impact on DL (β = 0.316, t = 4.516, p < 0.001). Hence, H1 is supported. H2 investigates whether RTDC has a positively significant effect on TVI. The results indicate that RTDC has a significant impact on TVI (β = 0.182, t = 2.606, p = 0.009). Hence, H2 is supported. H3 examines whether RTDC has a positively significant effect on FOMO. The findings reveal that RTDC has a significant impact on FOMO (β = 0.848, t = 32.777, p < 0.001). Hence, H3 is supported. Moreover, H4 investigates whether FOMO has a positively significant effect on DL. The findings demonstrate that FOMO has a significant impact on DL (β = 0.618, t = 9.296, p < 0.001). Hence, H4 is supported. H5 explores the relationship between FOMO and TVI. The results indicate that FOMO has a significant impact on TVI as well (β = 0.443, t = 5.075, p < 0.001). Hence, H5 is supported. Furthermore, H6 establishes that DL has a positively significant relationship with TVI. The results reveal that DL has a positive impact on TVI (β = 0.283, t = 3.326, p = 0.001). Hence, H6 is supported. Results are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Table 4.

Direct Hypotheses.

Mediating Analysis

The findings show that Fear of Missing Out significantly mediates the association between destination competitiveness and destination loyalty in regenerative tourism (β = 0.753, t = 22.159, p < 0.001), as well as mediates the relationship between regenerative tourism destination competitiveness and tourist visit intention (β = 0.450, t = 6.642, p < 0.001). The results of the mediating hypotheses are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mediating Analysis.

Moderating Analysis

The findings indicate that climate advocacy significantly moderates the relationship between Fear of Missing Out and destination loyalty (β = 0.045, t = 2.519, p = 0.012), as well as Fear of Missing Out and tourist visit intention (β = 0.209, t = 3.011, p = 0.003). However, the moderating effect of climate advocacy on the relationship between destination loyalty and tourist visit intention was statistically insignificant (β = 0.105, t = 1.089, p = 0.276). One possible explanation could be related to the specific cultural context of the UAE, where climate advocacy might not yet be a prominent factor influencing tourist behaviors as strongly as in other regions [49]. The UAE’s tourism industry, while increasingly attentive to sustainability, may still prioritize other factors such as luxury, convenience, and service quality over environmental concerns. This cultural context might diminish the impact of climate advocacy on tourists’ loyalty and their intention to visit. Additionally, the tourists’ varying levels of awareness and personal commitment to climate issues could affect how much climate advocacy influences their travel decisions [49]. Another factor could be the current state of climate advocacy initiatives in the UAE. If climate advocacy efforts are relatively new or not sufficiently integrated into tourism marketing strategies, their impact might be less pronounced. The effectiveness of such advocacy in moderating tourist behaviors may improve over time as awareness and engagement with environmental issues increase [46]. The results of the moderating hypotheses are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moderating Analysis.

5. Discussion

Global tourism plays a diverse role not only in the global economy but also in culture and society. Tourism hotspots may include fantastic national parks with a highly diversified environment, including majestic mountain ranges, mysterious archaeological sites, and intriguing cultural heritage, offering exciting leisure opportunities for both domestic and foreign travelers. Khalil, et al. [83] highlighted that tourism is a powerful vehicle for economic development through its local economic activities, including hotels, various forms of transportation, and local small-scale operations that provide employment, income, and financial stability for many residents of the area [80,81]. Tourism can also facilitate community development and empowerment. Substantial employment growth, eradication of illiteracy, and improved accessibility to housing and healthcare have been the results of tourism growth, as also analysed by Ullah, et al. [84]. When discussing the improvements made to the lives of locals living near tourism centres, it is evident that the diversity of various sites, historic locations, and cultural attractions greatly appeal to visitors to the UAE. This contributes to the development of the economy and the living standards of the country. This survey aims to reveal how RTDC, FOMO, and DL are influenced by climate advocacy conditions, which help develop the theoretical model of TVI. The study reports that results have been obtained except for H11, which is rejected. The present research study demonstrates that H1, regarding RTDC positively influencing DL, is supported, as well as H2 and H3, with RTDC showing positive and significant impacts on DL, TVI, and FOMO.

The study found that RTDC (Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness) has a significant positive impact on Destination Loyalty (DL), with the results showing β = 0.316, t = 4.516, and p < 0.001. Previous research on the relationship between tourism destination competitiveness and DL also supports this finding, indicating that RTDC positively affects DL [53,54]. Furthermore, this study identified that Tourism Destination Competitiveness has a significant positive impact on Tourist Visit Intention (TVI), with results of β = 0.182, t = 2.606, and p = 0.009. Previous studies have similarly noted that in the tourism context, destination competitiveness enhances the likelihood of tourists intending to revisit the destination [58,59]. Additionally, the research revealed that Tourism Destination Competitiveness has a significant positive impact on Travel Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), with results showing β = 0.848, t = 32.777, and p < 0.001. Past studies have emphasized that competitive destinations offer immersive experiences and novel activities that heighten FOMO among tourists [62]. According to Hypothesis 4 (H4), the study found that Travel FOMO significantly and positively affects Destination Loyalty. Previous research has also indicated that tourists, driven by FOMO, are highly attracted to desirable and beautiful tourist sites and are very conscious of opportunities to revisit their favorite places [62]. Hypothesis 5 (H5) suggested that Destination Loyalty plays a crucial role in increasing visit intentions. Studies have shown that loyalty can be enhanced by offering more benefits and services at desired destinations, which, in turn, motivates tourists to revisit the same destination [68]. The study found that DL has a significant positive impact on TVI, with results of β = 0.283, t = 3.326, and p = 0.001. Moreover, the impact of climate advocacy on destination loyalty and travel intention may vary significantly depending on the cultural context. In regions where cultural values do not align with prioritizing climate advocacy principles, the moderating effect may be much weaker or non-existent. By examining these relationships, this study contributes to understanding how tourism destination competitiveness, travel FOMO, and destination loyalty interact to influence tourists’ visit intentions.

Research studies associated with this field have demonstrated that more competitive destinations, offering exceptional experiences, good service levels, and possessing all the necessary facilities, will require fewer visitations to increase the level of satisfaction among tourists [51,52]. Yet, competitive destinations where tourists feel safe, observe cleanliness, and enjoy their aesthetic beauty gain strong positioning and experience an increase in visits and tourist activities [58,59]. Destinations competing in a saturated market and targeting tourists through the essence of sustainability and life-changing experiences will drive FOMO-based behaviours and commitments. Additionally, H4 and H5 postulate a high and meaningful link between Social Media Outlets and Anxiety Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [62]. On the other hand, this study demonstrated that FOMO positively and perceptually affected DL and TVI. These findings align with earlier research on the role of emotions and experience-based aspects of FOMO in creating destination loyalty [64]. The emotional and motivational aspects of FOMO impact tourists in such a way that they are compelled to visit attractions [66]. H6 shows that DL is positively and significantly correlated with economic income, and the assessment results indicate that the impact DL has on income is positive and significant as well. Among these principles, loyalty is a fundamental driver of repeat visitation, as identified in previous studies such as the example provided by Antón, et al. [23], where the author suggests that loyal tourists are more likely to return to a place and engage in repeated visitation behaviours. Furthermore, the results of hypotheses H7 and H8 obtained positive and significant values, which are also supported by previous investigations. Earlier content in the article showed that as tourists perceive a destination as competitive and appealing, it triggers experiences of Fear of Missing Out, which in turn strengthens the emotional attachment and loyalty towards the destination. There is a high probability of having competitors whose destinations spark FOMO among tourists and strong intentions to visit and engage in tourism activities [69,70]. First and foremost, not only are the direct effects or impacts of the current study positive, but there are also moderating effects hypotheses, with only H11 being statistically insignificant. Destination reputation is a highly generalized representation encompassing the broad spectrum of partial attributes that constitute destination image. In turn, destination image refers to the perception of the attributes of destination identity, as shaped by the individual perceptual filters of each person.

A recent paper by Matlovičová [85] delves into the distinguishing features and overlaps among these concepts. The author’s work provides clarity on the subject, addressing long-standing discussions and emphasizing the importance of recognizing these nuances to avoid misunderstandings. Another critical aspect to consider is that the negative impact of crises on destination loyalty varies depending on the level of digital technology adoption or the stage of digital transformation at each destination. In the context of the aforementioned polycrisis, digital solutions within Tourist Visit Intention, Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness, Destination Loyalty, and Climate Advocacy are integral to broader urban development plans and the transition to smart cities.

Smart destinations, which integrate advanced digital solutions, demonstrate higher levels of attractiveness and competitiveness. These smart solutions benefit not only tourists but also local residents, who experience significant impacts from tourism development—especially overdevelopment—on their quality of life. Over the long term, smart destinations enhance sustainability and minimize the risk of becoming tourist traps. For instance, Neumann [86] examines the development of smart districts, This study underscores the potential of smart districts to contribute significantly to the sustainability and competitiveness of tourist destinations.

6. Theoretical Implications

Utilizing the Game Theory, the present study adds value to several fields of thought in tourism and destination management research. Firstly, the confirmed relationships concerning Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness (RTDC), Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), Destination Loyalty (DL), and Tourist Visit Intention (TVI) contribute to our understanding of the psychological and behavioural factors influencing tourist decision-making processes. These relationships highlight the importance of destination appeal, emotional bonding, and experiential value as key factors driving travellers’ intentions and loyalty. On the other hand, the non-significant mediating effect of climate advocacy on the link between DL and TVI offers theoretical insights into the depth of understanding of green behaviour in tourism contexts. This highlights the need for a detailed investigation into tourists’ attitudes toward different environmental aspects and how they are interrelated to their behaviour.

The present study attempts multiple gaps, and in doing so makes important contributions. It is always recommended to number the contribution as first, second, third, and so on. Based on the identified gaps, the following research contributions are identified. In this case, the first contribution is based on the relationship between IVs and DV and is written as: The present study aimed to utilize the Game Theory to observe the connections among RTDC, FOMO, DL, and TVI, with the moderating role of CA. These factors are essential for increasing the ratio of tourists at specific destinations. Additionally, in this research, FOMO works as a mediator between RTDC and DL, as well as between RTDC and TVI, specifically in tourist sites in the various regions of the UAE. In this context, very few studies are identified in the UAE that explore these variables collectively, there is a need for more research to improve tourists’ motivation to explore the UAE.

Second, some researchers have conducted studies individually on these topics in previous years, but in the UAE context they have not studied the interplay among these factors [17,18]. In the UAE, to understand the factors regarding how tourist sites can maximize the attention of tourists to explore these destinations, more studies are needed to identify the relationship among these factors. Further research is needed to address these gaps. Third, additionally, FOMO has been studied in different contexts, like social media marketing, consumer behaviour, customer loyalty, and other areas in previous studies [19,20], but in the area of tourism, FOMO has not been examined extensively. So, in the UAE context, it is needed to conduct further studies on this potential topic.

7. Practical Implications

Based on the extensive applications of the Game Theory, this paper holds profound practical significance for the tourism community, government agencies, and destination managers. The impact of TDC on the increase of FOMO, DL, and tourist visits to destinations indicates that considering strategies for developing destinations aimed at achieving competitiveness, uniqueness, and visitor experiences will lead to an increase in tourist visits and loyalty. Additionally, while no significant mediation occurs between Climate Advocacy and DL, TVI suggests that the information provided by visitors and recognition of tourists’ attitudes will make sustainable tourism practices more important. Consider including eco-tourism movements in map pointers to attract mindful tourists and enhance the destination’s attractiveness.

Thus, based on the Game Theory concepts, this work has important practical implications for numerous stakeholders within the context of tourism. It implies that government agencies need to take some of the significant findings into account to develop more sustainable policies related to the creation and enhancement of the competitiveness of tourism in the chosen destinations. In this light, improving the FOMO, DL, and tourism visitation can help policymakers and economic development without compromising on cultural and environmental endowments. Destination managers can leverage the findings related to RTDC, FOMO, and DL by implementing targeted marketing strategies that emphasize exclusivity and unique experiences. By highlighting aspects of the destination that are difficult to replicate elsewhere, such as limited-time events or unique cultural attractions, they can create a sense of urgency that taps into tourists’ FOMO. Storytelling techniques, including the use of compelling narratives about the destination’s history and cultural significance, can further enhance this effect. Collaborations with travel influencers who can authentically share their experiences can also amplify FOMO among their followers, driving interest and increasing visits.

In terms of sustainability efforts, destination managers can integrate and promote eco-tourism activities as part of their offerings. Highlighting these initiatives in marketing campaigns can attract environmentally conscious tourists who prioritize responsible travel. This not only enhances the destination’s appeal but also contributes to its long-term sustainability. Encouraging visitors to share their positive experiences and sustainable practices on social media can build a community of advocates, strengthening destination loyalty as tourists who feel connected to the destination’s values are more likely to return and recommend it to others. Additionally, implementing and promoting sustainable resource management practices positions the destination as a responsible choice, appealing to tourists who value sustainability. To enhance visitor experiences, destination managers can use data on visitor preferences to offer personalized and customized experiences that cater to individual interests. This can significantly enhance visitor satisfaction and foster destination loyalty, as tourists are more likely to return to a destination that offers tailored experiences. Developing unique attractions that cannot be easily replicated elsewhere, such as cultural festivals, local culinary experiences, or interactive workshops, can also contribute to both FOMO and destination loyalty, ensuring that the destination remains competitive and appealing in a post-shock era.

These findings can be useful for the tactical and strategic planning of tourism managers to improve customers’ experience and build travelers’ destination commitment. Several studies have deemed the focus on being different from competitors, having unique products, and providing superior experiences to visitors as strategies that could help enhance visitors’ satisfaction and the number of revisits. Also, promoting eco-tourism activities and sustainable use of natural resources in the development of a destination can pull in responsible tourists improving on the appeal and sustainability status of the destination. Thus, by adopting and implementing these findings, all the stakeholders in the tourism system can enhance industry competitiveness in a post-shock era. It not only addresses the new generations’ more responsible travel patterns but also lays down the future foundation for destinations in a competitive environment.

8. Limitations of the Study

While this study provides significant insights into the relationship between variables, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the study’s reliance on convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings. Although the sample size was determined using established guidelines and was sufficiently large, the use of non-probability sampling means that the results may not fully represent the broader population of tourists, especially those who were not included in the sample. Future research could employ a probability sampling technique to enhance the representativeness of the findings. Secondly, the study was conducted within the specific context of the UAE’s tourism sector, which may limit the applicability of the results to other regions. The unique cultural, economic, and environmental characteristics of the UAE may have influenced the relationships between the variables studied. Consequently, the findings may not be entirely generalizable to other countries or regions with different tourism dynamics. Future studies could replicate this research in different contexts to examine whether the observed relationships hold in other settings.

Thirdly, the cross-sectional nature of the study presents another limitation. The data were collected at a single point in time, which restricts the ability to draw causal inferences between the variables. While the study provides strong evidence of associations, it does not establish causality. Longitudinal studies could be conducted in the future to track changes over time and provide more robust evidence of causal relationships. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on the mediating role of FOMO and the moderating role of CA, potentially overlooking other factors that might influence DL and TVI. Variables such as cultural differences, economic conditions, or specific tourist motivations were not accounted for in this study. Future research could explore other mediators and moderators to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing tourist behavior in the context of regenerative tourism. Finally, the study utilized self-reported data, which can be subject to biases such as social desirability or recall bias. Participants may have provided responses they believed were socially acceptable or may not have accurately recalled their experiences. Future research could incorporate objective measures or triangulate self-reported data with other data sources to mitigate these biases.

9. Future Recommendations

Despite the valuable data provided by the study, there are also some weaknesses. The research was conducted in a specific setting (for example, tourist destinations in the UAE), making it difficult to generalize the results to other contexts. We encourage researchers to engage focus groups representing various cultural contexts such as individualism vs. collectivism to enable real-world generalization of the research findings. Additionally, while this study focused on selected variables such as Fear of Missing Out, Tourism Destination Competitiveness, Destination Loyalty, Tourist Visit Intention, and Climate Advocacy, pertinent information that could guide decision-making and tourist behaviours (such as socio-demographic factors and destination image) were only briefly touched upon. Additionally, examining communication styles and cultural adaptation could enhance understanding of cross-cultural interactions in tourism. Future researchers are advised to examine a wide array of variables to create a highly integrated and comprehensive scenario, rather than focusing on one or two dimensions. The competitiveness of tourist destinations must be evaluated considering the synergistic impact of the global polycrisis. Each aspect of this polycrisis—whether environmental, economic, social, political, technological, geopolitical, or health-related (such as the COVID-19 pandemic)—independently influences the competitiveness of destinations. However, the compounded effects of these crises create unique challenges that are not adequately addressed in the current literature. Climate advocacy, while critical, represents only one dimension of the broader polycrisis affecting tourism.

Today, destinations face a convergence of crises that together form a complex and interconnected web of challenges. This polycrisis paradigm highlights the difficulty of isolating and examining individual aspects without considering their mutual interactions and cumulative impacts. Matlovič and Matlovičová [87] emphasize the importance of understanding this polycrisis within the context of the Anthropocene, advocating for a postdisciplinary approach to geographic research. Their approach provides a more holistic understanding necessary for developing effective strategies to enhance the competitiveness of tourist destinations amid such multifaceted challenges. Therefore, recognizing and addressing the synergistic effects of the polycrisis is crucial for any thorough analysis of the competitiveness of tourist destinations [88]. Future research should incorporate this perspective to develop more robust and resilient strategies for the tourism sector.

10. Conclusions

The conclusions of this research imply that RTDC has a positive influence on FOMO, DL, and TVI, and the mediating role of Fear of Missing Out is to enhance the impact of RTDC on these latent constructs, i.e., DL and TVI [89,90]. After review and statistical validation via PLS-SEM, the hypothetical assumptions (H1–H10) were accepted. It has been found that there are strong and positive relationships between Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness (RTDC), Tourist Visitation Intention (TVI), Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), and Destination Loyalty (DL). Specifically, the level of RTDC influences FOMO, DL, and TVI, suggesting that destination appeal and competitiveness are relevant factors in influencing tourists’ perceptions and intentions. Importantly, Climate Advocacy (in the context of UN Sustainable Development Goal 13 emphasizing on climate action) significantly moderates the impact of FOMO on DL and TVI [85,89,91]. However, Hypothesis 11, which outlined how Climate Advocacy acts as a moderator of the link between Tourism Destination Loyalty (DL) and Tourist Visit Intention (TVI), was not supported by the data, illustrating a non-significant moderating effect. Nevertheless, DL still individually influences TVI, although this effect does not significantly vary depending on the purpose of tourism to a particular area among the tourists in our present study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Endicott College of International Studies (ECIS) Departmental Internal Review; approval number: ECIS/2024/1/M/63 (dated 3 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was secured from all participants who had volunteered to participate in this academic research.

Data Availability Statement

The study data are available on special request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Scale Items of All Measures

Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness—Adapted from [88].

- “I always consider factors such as accessibility, transportation options, and overall connectivity when choosing a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the quality of infrastructure (e.g., hotels, restaurants, and entertainment options) when choosing a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of natural and cultural attractions when choosing a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the level of safety and security of a regenerative tourism destination when making travel plans”.

- “I always consider the level of environmental sustainability and responsibility reflected by a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of tourist services (e.g., tour guides, tourism information centers, and tourist-friendly policies and regulations) when choosing a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of digital technologies and online services (e.g., free Wi-Fi, online booking systems, and mobile applications) when choosing a regenerative tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the cost of travel, accommodation, and other tourism-related expenses when deciding on a regenerative tourism destination, and how it balances with quality and experience”.

Travel FOMO—Adapted from [92].

- “I feel anxious when I do not experience travel opportunities”.

- “I believe I am falling behind compared with others when I miss travel opportunities”.

- “I feel anxious because I know something important or fun must be happening when I miss travel opportunities”.

- “I feel sad if I am not capable of traveling due to constraints of other things”.

- “I feel regretful of missing travel opportunities”.

- “I think my social groups view me as unimportant when I miss travel opportunities”.

- “I think I do not fit in social groups when I miss travel opportunities”.

- “I think I am excluded by my social groups when I miss travel opportunities”.

- “I feel ignored/forgotten by my social groups when I miss travel opportunities”.

Destination Loyalty—Adapted From [93].

- If I revisit, the UAE will be my first choice in the Middle East.

- I am considering revisiting the UAE in the future.

- The probability that I come to the UAE again for holidays is high.

- I will say positive things about the UAE to those around me.

- I will encourage those around me to come to the UAE.

- I will recommend the UAE to other people.

- When asked about a holiday destination I will recommend the UAE.

Tourist Visit Intention—Adapted from [31].

- In recent years, if I plan for an outbound travel, I will visit the UAE.

- If I plan a trip to the Middle East, I will visit the UAE.

- In short, I think the UAE is a good place deserving a visit.

Climate Advocacy—Developed From [72,73,94].

- “I actively participate in events or activities aimed at raising awareness about climate change”.

- “I frequently discuss the importance of climate action with my friends, family, or colleagues”.

- “I support policies and initiatives that aim to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change”.

- “I regularly share information about climate change and environmental issues on social media or other platforms”.

- “I engage in or contribute to organizations or groups that advocate for environmental protection and climate action”.

- “I encourage others to adopt sustainable practices and reduce their environmental impact”.

References

- Pappas, N. Marketing strategies, perceived risks, and consumer trust in online buying behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan, M.; Zaman, U.; Nawaz, S. Examining destinations’ personality and brand equity through the lens of expats: Moderating role of expat’s cultural intelligence. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidebo, H.B. Factors determining international tourist flow to tourism destinations: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Tourism Management and Marketing in Transformation: Preface. 2022. Available online: http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/35108/1/ENCYCLOPEDIA%20TMM%20Preface%2025Jan21_em%20PREFACE.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Cronjé, D.F.; Plessis, E.D. A review on tourism destination competitiveness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Prideaux, B.; Thompson, M. The relationship between accommodation type and tourists’ in-destination behaviour. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Gazzaley, A. The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan, M.; Shekhar, S.K. A study on the mediating effect of FoMO on social media (instagram) induced travel addiction and risk taking travel behavioral intention in youth. J. Content Community Commun. 2021, 14, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-K.; Chen, Y.-C. Tourists’ work-related smartphone use at the tourist destination: Making an otherwise impossible trip possible. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1526–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosvi, H.; Bambang, H.; Iwan, S.; Zeis, Z. Destinations’ competitiveness through tourist satisfaction: A systematic mapping study. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2019, 91, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Chon, K.; Ro, Y. Antecedents of revisit intention. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.-C.; Chin, C.-H.; Law, F.-Y. Tourists’ perspectives on hard and soft services toward rural tourism destination competitiveness: Community support as a moderator. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, M. Applying advocacy in climate change. In The Case of Bangladesh: Media Meets Climate: The Global Challenge for Journalism; Teoksessa Eide, E., Kunelius, R., Eds.; Nordicom: Göteborg, Sweden, 2012; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Zulkifly, M.I. Tourism destination competitiveness and tourism performance: A secondary data approach. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2019, 29, 592–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Costa, C.; Ford, F. Tourism Business Frontiers; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jood, T.E. Missing the Present for the Unknown: The Relationship between Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and Life Satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, H.; Yuliantini, T.; Raharja, I.; Samudro, A.; Ali, H. Establishing Collaborate and Share Knowledge as a Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) Response in Improving Tourist Travel Agency Innovation Performance; BISMA (Bisnis dan Manajemen): Surabaya, Indonesia, 2023; pp. 115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Psychological determinants of tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The influence of perceived overcrowding and overtourism. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V.; Jaunky, V.C. The tourist experience: Modelling the relationship between tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 37, 2284–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna-Garcia, M. Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenini, A.; Touaiti, M. Building destination loyalty using tourist satisfaction and destination image: A holistic conceptual framework. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2018, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyarini, N.W.M.; Rahmanita, M.; Setarnawat, S. The influence of destination image on tourist intention and decision to visit tourist destination (A case study of Pemuteran Village in Buleleng, Bali, Indonesia). TRJ Tour. Res. J. 2017, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, H.A.K.; Wafik, G.M.; Gerges, N.W. The impact of motivations, perceptions and satisfaction on tourists loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2016, 9, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B. Shaping tourists’ destination quality perception and loyalty through destination country image: The importance of involvement and perceived value. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lv, X.; Scott, M. Understanding the dynamics of destination loyalty: A longitudinal investigation into the drivers of revisit intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpikul, A. The influences of destination quality on tourists’ destination loyalty: An investigation of an island destination. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2017, 65, 422–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. Exploring the influence of electronic word-of-mouth on tourists’ visit intention: A dual process approach. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Putra, T.R.I.; Yunus, M. The effect of e-WOM model mediation of marketing mix and destination image on tourist revisit intention. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 7, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Crompton, J.L. Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Huang, S.S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Tourist inertia in satisfaction-Revisit relation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 82, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramudhita, N.D.E.; Madiawati, P.N. The role of social media marketing activities to improve e-wom and visit intention to Indonesia tourism destinations through brand equity. J. Sekr. Dan Adm. Bisnis 2021, 5, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Mediating tourist experiences: Access to places via shared videos. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travellers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]