Abstract

This study aims to investigate how sustainability communication on social media, by retail fast-food chains, affects fast-food consumer behavior in terms of ascribed responsibility, felt obligation, and green values for the promotion of sustainable actions. Data-based evidence from fast-food customers in Malaysia established that sustainability communication increases the awareness of responsibility and moral obligation to behave sustainably. The findings of this study show that sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains leads to the improvement of the eco-conscious behavior of fast-food consumers. This relationship is mediated by psychological factors such as ascribed responsibility and felt responsibility and moderated by green values. The results of this study show that Malaysian customers who feel more responsible and obligated are likely to participate in sustainable behaviors. Furthermore, the high levels of green values enhance the impact of sustainability messages, meaning that sustainable communication can indeed change consumer behavior. This study supports the role of social media in improving the communication of sustainability and adapting the message to consumers’ values. These findings offer useful insights for fast-food firms that wish to enhance their sustainability initiatives and support the overall goals of sustainable development. This research also enhances the theoretical knowledge by incorporating both psychological and value-based factors into the model of sustainability communication, providing further insights into the effects of the factors on consumer behavior. This research thus offers a theoretical extension to the sustainability communication literature by considering psychological and value-based factors and offers practical implications for fast-food chains to enhance their sustainability communication and support sustainable development goals.

1. Introduction

In the last few years, the issue of climate change and the need to embrace sustainable measures has been at the forefront. This pressure is due to the rising trends in the occurrence and intensity of climate-change-related disasters across the globe such as the recent heat waves in Europe [1], floods in South Asia [2], and the fires in North America and Australia. These events have highlighted the importance of acting quickly and in unison, with all stakeholders, such as companies, states, and citizens. As climate impacts worsen, businesses are increasingly addressing these challenges, recognizing their role in global sustainability efforts [3,4]. Today’s consumers are more cautious of a company’s environmental and social impact, driving businesses to embed sustainability into their core strategies [5]. The main consequences of the failure to implement sustainable initiatives are reputational loss and market share shifts to competitors who act sustainably [6]. With billions of active users, social media has enhanced the significance of corporate sustainability by altering the manner in which companies interact with consumers [7,8]. It creates an active dialogue where one can pass information on the functioning of the companies and their sustainability measures [9,10]. Starbucks and Unilever, for instance, utilize social media to communicate information on their sustainability policies and, therefore, influence consumers with sustainability sensitivity [11,12].

This study aims to determine the effectiveness of sustainability-related communication of retail fast-food chains on customers’ eco-consciousness in the context of social media. Thus, the fast food industry has been one of the most discussed industries in the context of globalization [13]. This sector is under immense pressure to change its operations, given that it uses a lot of single-use plastics, produces a lot of food waste, and has a high carbon footprint. McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Burger King among other multinational companies have come up with measures to address this issue. For instance, McDonald’s has committed to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 36% by 2030 and switch to more sustainable packaging [14], while Starbucks has set goals to become ‘resource positive’ by eliminating single-use plastics and encouraging reusables [15]. These commitments are in line with the general trend of sustainability in the industry, but they also show how companies struggle to change their business strategies to changing consumers’ needs and wants. Considering this, our research aims to examine how sustainability communication by fast-food chains affects consumers’ eco-conscious behavior. Given the fact that this industry has a great influence on society and the fact that more and more people are concerned about the environment and its protection, it is essential to discuss this issue to learn more about the possibilities of how companies can contribute to the positive change in the environment.

Sustainability is a rather complex term [16,17], which includes a number of practices and principles that are meant to help people meet their current needs without endangering the ability of future generations to meet their needs [18,19]. Within the context of this study, sustainability is defined across three interrelated dimensions: environmental, economic, and social impacts. The environmental aspect involves the management of the environmental impacts of business activities through the reduction in wastes, efficient use of resources and energy, and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [20,21]. For the fast-food industry, this entails measures such as minimizing the wastage of food, using degradable packaging materials, sourcing food from nearby local farmers, and using efficient means of preparing food. The economic aspect of sustainability is the ability to generate enough income in the future through proper business practices that are in line with changing consumer values of society. It encompasses the achievement of corporate goals while adopting social responsibilities like correct pricing, proper sourcing, and proper supply chain communication. The social aspect, on the other hand, encompasses ethical issues including the provision of decent work, maintenance of decent working conditions, and social development of communities. Thus, incorporating these dimensions, sustainability is a comprehensive concept that complies with current consumer values and benefits the company’s image and market position. In this context, we discuss the effects of sustainability communication on consumer behavior in the fast-food industry and stress the necessity to consider all three dimensions for sustainable strategies to be effective.

The fast-food industry’s environmental impact necessitates examining how companies address sustainability and engage consumers via social media, a key communication tool influencing sustainable choices [22]. Understanding consumer perception of these messages and their influence on sustainable decisions is essential. This study contributes to business sustainability by linking corporate sustainability communication with consumer values and social media presence. It analyzes psychological and personal factors, such as perceived responsibility and personal obligation, which motivate eco-friendly actions, as well as cultural and personal environmental beliefs. The framework posits that ascribed responsibility and felt obligation mediate the relationship between sustainability communication and green behavior. Ascribed responsibility refers to consumers’ perceived self-responsibility for environmental outcomes aligned with business strategies [23], while felt obligation denotes an ethical duty to act on sustainability messages [24]. Additionally, consumers’ green values are proposed as a moderator, reflecting their environmental concern and influencing the impact of sustainability communication on eco-conscious behavior. By integrating these psychological and value-based aspects, the framework provides insights for businesses to influence consumer behavior regarding climate risk and sustainability, offering practical implications for enhancing sustainability initiatives.

Since climate change affects every region in the world and not all people are aware of the consequences [25,26], it is necessary to situate this research within a particular geographical and cultural environment. Malaysia, as a rapidly developing country with increasing urbanization, presents a unique environment in which to examine the nature of sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains and the resulting environmentally conscious behavior. In recent years, Malaysia has paid more attention to sustainability at the national level and the corporate level, and it is an appropriate context to investigate how firms can change consumers’ purchase intentions through sustainability messages. This focus on Malaysia improves the knowledge of sustainable consumer behavior in developing nations and provides suggestions for encouraging environmentally friendly practices in similar markets. The fast-food industry in Malaysia has been growing at a very high rate in the last few decades due to factors like increased population density, the emergence of middle-income earners, and changes in society’s lifestyle where people have less time to prepare their meals [27]. Some of the popular fast-food chains such as KFC, McDonald’s, and Subway have also spread their branches across the country and have also created employment opportunities. As of 2022, the food service industry, which encompasses fast food, earned more than MYR 80.9 billion (USD 18.4 billion) in revenue and provided numerous jobs throughout the country [28]. But this growth is not without some negative impacts on the environment and society. The Malaysian fast-food industry is known to consume a large quantity of single-use plastics, excessive packaging, and high energy usage. Most of the outlets still use non-biodegradable products, which is not good for the environment, especially with the increasing waste management issue in Malaysia. A survey conducted by the Ministry of Environment and Water in the year 2023 revealed that the food and beverage industry generated a high percentage of packaging waste in the country, with plastics contributing to about 30% of total solid waste. With the awareness of these problems among Malaysians, there is a rising concern for the improvement of sustainability from fast-food companies. This is a problem and a potential issue on the part of the industry. Therefore, sustainability initiatives, if well communicated through social media platforms, can help the fast-food chains in Malaysia to minimize their environmental impacts while at the same time capturing the market of environmentally conscious consumers.

Despite extensive research on sustainability communication and consumer behavior, gaps remain, especially in emerging markets. To begin with, although prior studies in the literature have focused on the effects of corporate sustainability practices on consumer outcomes, few studies have investigated the effects of sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains on environmentally responsible behavior in developing countries such as Malaysia. Moreover, the bulk of the surveys are conducted in Western countries where people are more conscious about the environment, and their expectations are also high. This geographic and cultural bias poses a challenge to current findings, and it hampers the chances of establishing how sustainability communication can be effectively enacted to different consumers. On a further note, while previous studies have explored mediating and moderating factors in the context of sustainable brands and consumer behavior, the mediating roles of ascribed responsibility and felt obligation and the moderating role of green value have not been explored in the context of the fast-food industry, in a unified model. In our opinion, it is important to know these factors because they show how psychological and value-based factors transform sustainability messages into consumers’ actions as mentioned by Ahmad, et al. [29]. Investigating these variables can reveal how consumers incorporate sustainability communication-related information that is critical for companies that seek to encourage sustainable consumption.

Similarly, despite the fact that the moderating role of environmental values has been investigated in different settings [30,31], the moderating effect of fast-food customers’ green values in the fast-food industry, especially in the Malaysian context, has received limited empirical attention. Considering the increase in the awareness of environmental responsibility, it is essential to know how these values affect the sustainability communication–consumer behavior relationship. Thus, studying this moderation effect is useful to understand how to adapt sustainability communication to various consumer groups. Furthermore, despite the effectiveness of social media as a communication platform, the effectiveness of sustainability communication, particularly in influencing eco-conscious behavior through social media, is still relatively in its infancy stage, particularly in the context of developing economies. Since social media plays a crucial role in the consumer decision-making process, the following research question should be raised: How can social media be utilized more effectively to support sustainability in emerging markets such as Malaysia?

Our research addresses these gaps by proposing a dual mediating mechanism involving fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility and felt obligation and by examining the moderating role of fast-food customers’ green values. This study bridges research gaps and offers a nuanced understanding of how sustainability communication influences eco-conscious behavior in a specific cultural and industrial context. Focusing on Malaysia enhances this study’s relevance, providing insights into sustainable consumer behavior in a rapidly developing market, an often-overlooked perspective. This approach offers businesses actionable insights to refine their sustainability strategies, making them more effective in culturally diverse settings.

2. The Literature and Hypotheses

2.1. The Role of Sustainability Communication in Consumer Behavior

Social media has been seen as a good platform for communicating sustainability to consumers to influence their behavior [32]. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are some of the social media platforms that afford brands the chance to post sustainability messages and influence consumers in terms of brand choice and consumption. These platforms have been adopted by companies such as Patagonia and The Body Shop, among others, to promote environmental causes and therefore enhance consumer engagement [33]. Sustainability communication by fast-food chains relates to how the companies share information on their environmentally friendly activities on their social media pages such as reducing carbon emissions or the use of environmentally friendly packaging [9]. Such initiatives can benefit from social media, as it facilitates communication with many consumers and creates a dialogue that helps to promote the sustainability messages of the brands [34]. The eco-conscious behavior of fast-food customers is defined by the consumers’ decision to purchase products from sustainable brands, select green products from the menu, and minimize waste [35]. This change in consumer behavior is as a result of sustainability communication, which influences attitudes and behaviors. This linkage is enhanced by social media, as it makes sustainability activities more interactive and easier to adopt by consumers, thereby influencing them to make the right decisions on the products to purchase that are in line with the brand’s sustainability goals.

This research is grounded in signaling theory, which explains how firms communicate sustainability objectives to consumers who cannot monitor internal processes. Previous studies have applied signaling theory to assess the impact of CSR messages on consumer perceptions and behaviors. For instance, Hysa, et al. [36] examined how sustainability communication on social media affects trust and loyalty, while Chavez-Olivera, et al. [37] explored sustainability signaling in the fast-food industry. Al-Adwan, et al. [38] used the theory to investigate online purchasing intentions in e-retailing. These studies show that signaling theory effectively explains how consumers interpret sustainability messages, perceive brand commitment, and change buying behavior. We use signaling theory to understand how sustainability communication by fast-food chains in emerging markets like Malaysia reduces information asymmetry, builds trust, and promotes pro-environmental behavior through ascribed responsibility and felt obligation.

H1.

Sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains through social media positively influences fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

2.2. Ascribed Responsibility and Its Impact on Eco-Conscious Behavior

Sustainability communication by brands is one of the factors that play a significant role in the shaping of customers’ perception of sustainability [39]. When brands share their sustainability measures, they raise awareness on matters of sustainability and put emphasis on the part that the company and consumers play in the sustainability process [36]. For example, when a brand comes up with a campaign of reducing the carbon footprint or using environmentally friendly products, it informs the consumer that being responsible is everyone’s business. In our study, sustainability communication by fast-food chains has the same effect on customers’ ascribed responsibility. By sharing information about their environmental practices on social media, these chains imply that it is a collective effort to promote such causes and change customers’ behavior, particularly in countries that are gradually paying attention to environmental issues [40]. In the context of this study, the relationship between fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility and eco-conscious behavior is significant since it shows how the consumers’ awareness of the environment is taken into account. If people are made to believe that they have a part to play in sustainable consumption, then they will be more likely to act in a way that will support this cause, for instance using products that are not hazardous to the environment or purchasing products from brands that support sustainability [41]. Therefore, the fast-food industry is an appropriate context to examine this correlation. It can be argued that when chains come forward to reveal their sustainability practices, customers who are more sensitive to their responsibilities opt for products that are eco-friendly, and this is a trend that has been observed especially in sectors that are detrimental to the environment [37]. Previous studies show that companies’ sustainability messages shape consumers’ sense of responsibility. Kapoor, et al. [42] found that disclosing sustainability policies makes consumers feel involved and motivates environmental protection, creating a collective action frame that links awareness to action. Ascribed responsibility is crucial for eco-conscious behavior, as individuals who perceive their actions as impacting the environment are more likely to act pro-environmentally [43]. Wu and Yang [44] demonstrated that feeling accountable alongside businesses increases environmentally friendly behaviors, while Abdou, et al. [45] showed that high perceived responsibility leads to support for eco-friendly brands. Additional research supports ascribed responsibility’s role in green consumption, with Verma, et al. [23] linking it to pro-environmental purchasing in green apparel and Dong, et al. [46] noting that environmentally conscious consumers purchase low-carbon products and support sustainable businesses. Moreover, ascribed responsibility mediates the relationship between sustainability communication and consumer behavior. Therefore, this study proposes that ascribed responsibility mediates the relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains and customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

As per the signaling theory, when firms convey their sustainability standards, they change consumers’ attitudes and emotions [47]. When consumers receive these signals, they may feel that they have no choice but to act in a ‘green’ manner, which is the connection between sustainability communication and customer behavior. Thus, signaling theory enables identifying how sustainability communication by fast-food chains affects consumer responsibility, which results in the adoption of environmentally responsible actions and makes ascribed responsibility the crucial mediator of this connection. Based on this line of research, we propose that when fast-food consumers feel that they are responsible for the environment, they will act in an environmentally friendly manner. Hence, we propose that fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility has a positive effect on fast-food customer eco-conscious behavior.

H2.

Sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains positively influences fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility.

H3.

Fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility positively influences fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

H4.

Fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility mediates the relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

2.3. Felt Obligation and Consumer Motivation for Sustainable Actions

Sustainability communication by a brand affects the customer responsibility of the customer, particularly their perceived responsibility [48]. When brands are able to communicate their sustainability initiatives effectively, they are able to foster a sense of responsibility among consumers to ensure that they stick to the brand’s cause. This is especially the case when the communication is frequent, comprehensible, and aligns with the consumers’ self-identified values [49]. In our study, customers felt obligation could be influenced by fast food chains’ sustainability communication. Since these chains propagate environmentalism in their business operations, for instance in waste management or the use of environmentally friendly products, customers will probably feel that they owe the chains their patronage. This felt obligation of customers can be especially important in areas where the awareness of the environment is increasing [50]. This may lead to the customers perceiving the brand’s efforts and being motivated to make sustainable choices.

When customers feel a responsibility to preserve the environment, it has a profound effect on their behavior, especially their environmental behavior [51]. Consumers feel that when there is responsibility, there are actions that are taken, such as choosing environmentally friendly products or reducing the impact on the environment. This obligation plays the psychological motivation role that changes consumer status from awareness to action by changing their buying behavior. In the fast-food industry, for instance, it may mean not throwing away food or using environmentally friendly packaging. In particular, those consumers who are motivated by guilt are more likely to engage in environmentalism and therefore stress the importance of adequate communication on sustainability. More informative is the mediator impact of felt obligation as far as the relationship between sustainability communication and actual eco-conscious behavior is concerned. According to signaling theory, the message that brands communicate about their sustainability activities affects consumers’ personal values, including felt obligation [52]. This obligation describes how consumers move from the awareness of sustainability messages to a change in their behavior. Signaling theory is useful in studying how messages affect consumers’ behaviors because it views messages as signals that induce change and is particularly pertinent for sustainability communication where brand identity is important and messages need to be kept simple.

H5.

Sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains positively influences fast-food customers’ felt obligation.

H6.

Fast-food customers’ felt obligation positively influences fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

H7.

Fast-food customers’ felt obligation mediates the relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior.

2.4. Green Values as Moderators of Sustainability Communication

Human values are key in shaping behavior and guiding decisions across contexts. Personal values like environmental stewardship and altruism strongly influence how individuals respond to stimuli, including marketing [53]. These values drive behaviors aligned with one’s beliefs. For instance, those prioritizing environmental stewardship are more likely to support sustainable practices, while those valuing social responsibility may favor fair trade businesses [30]. It is also noted that values regulate behavior formation even more when they are congruent with external messages, thus enhancing the stability of behavioral intentions [54]. In the same way, when a message is congruent with a person’s core values, then the message will create action [55]. On the other hand, if the message does not fit into the consumer’s framework, then the consumer will not be motivated to change his/her behavior.

In the context of the fast-food sector, the green value of customers can moderate the extent of sustainability communication and eco-conscious behavior regulated by ascribed responsibility and felt obligation. The message regarding sustainability is likely to be well received by consumers with high green value, as the message aligns with their values [56]. When a consumer receives a signal from the brand that the brand cares for sustainability, the consumer takes it as their responsibility to contribute to sustainability, hence practicing sustainable behavior. It also increases the impact of the sustainability messages since consumers are placed in a position to assume the responsibility of sustainability. This is amplified by social media, where brands can continue to nudge the consumer, making them feel responsible and engage in environmentally friendly behaviors. Similarly, consumers with high green values may feel pressured when they realize that a particular brand aligns itself with sustainability. This obligation is even higher when the messages from the brand they follow are congruent with their attitude, and this compels them to behave in an environmentally friendly manner [57]. Social media ramps this up by offering an immediate means of engaging and publicly reinstating the shared commitment to be part of the process of encouraging sustainability. In sum, fast-food customers’ green value can be regarded as a significant moderator between sustainability communication and eco-conscious behavior, particularly with the mediating roles of ascribed responsibility and felt obligation. Thus, the messages that are associated with consumers’ green values are more likely to be incorporated and result in responsible behavior of the brand. This emphasizes the need to ensure that sustainability communication is carried out in a way that appeals to the consumer’s value system, especially on social media where messages can be customized to have the highest effect. Hence the following hypothesis can be posed:

H8.

Fast-food customers’ green value moderates the mediated relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior through fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (H8a) and through fast-food customers’ felt obligation (H8b), such that the relationship is stronger when green values are high.

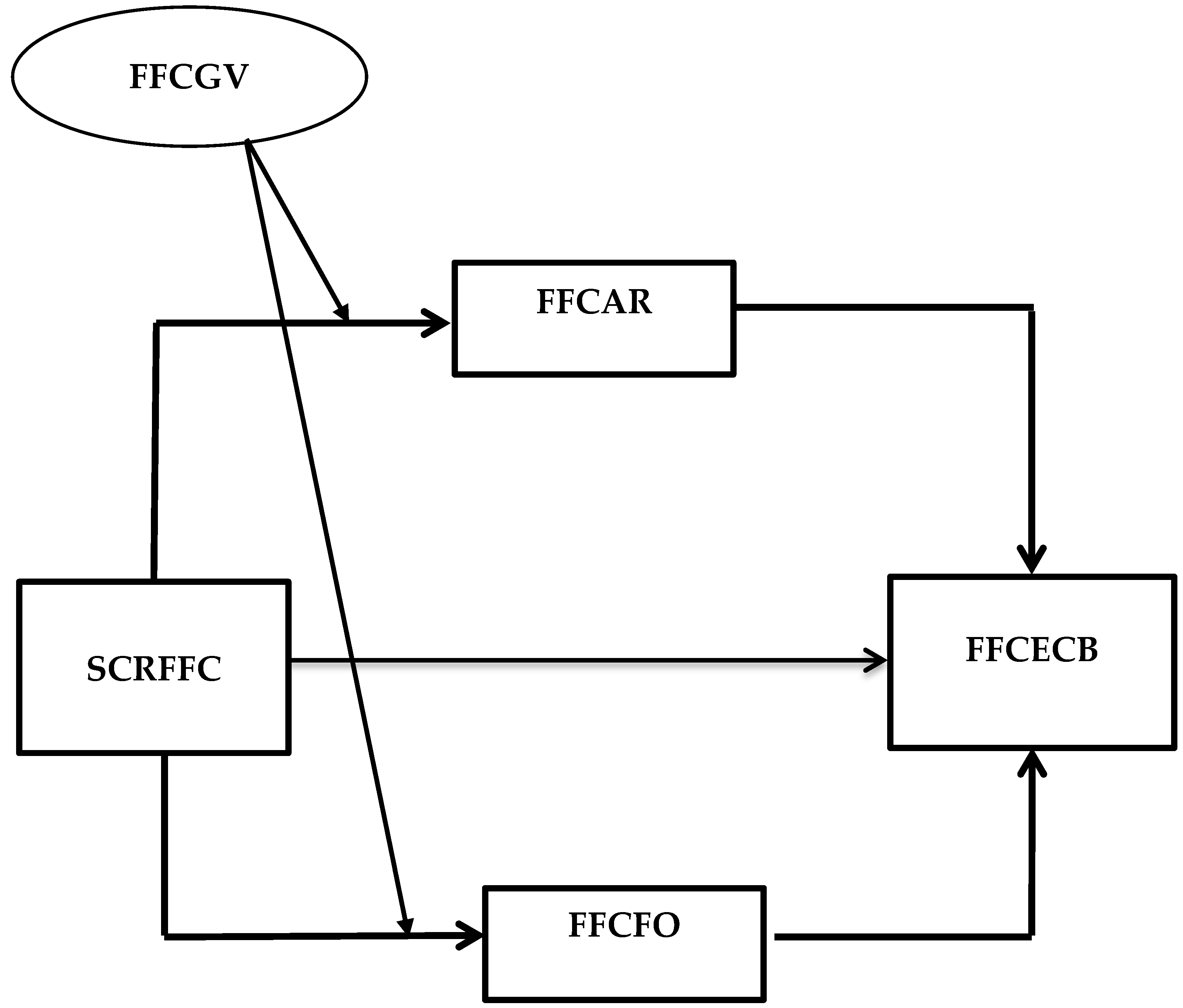

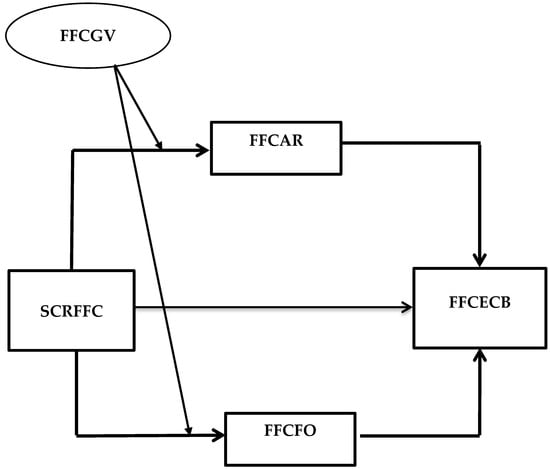

Figure 1 represents our conceptual model demonstrating how sustainability communication influences eco-conscious behavior through the mediating effects of ascribed responsibility and felt obligation, with green values moderating these relationships.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model: sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC), fast-food customers’ green value (FFCGV), fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (FFCAR), fast-food customers’ felt obligation (FFCFO), and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior (FFCECB).

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected using structured face-to-face questionnaires distributed to fast-food customers in Kuala Lumpur, George Town, and Johor Bahru, Malaysia. These cities were chosen for their high population density, cultural diversity, and concentration of fast-food chains. Surveys were conducted at outlets with active sustainability initiatives communicated through social media, excluding those without clear sustainability strategies. Using G*Power 3.1, a sample size of approximately 400 was determined. We distributed 600 questionnaires and received 447 responses (74.5% response rate). After excluding incomplete or unreliable responses, 409 questionnaires were included in the analysis, exceeding the required sample size. Ethical considerations were thoroughly addressed. Ethical approval was obtained, and informed consent was secured from all respondents, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity [58,59,60]. The participants were informed of this study’s purpose, their right to withdraw, and measures to protect their personal information. The data were securely stored, accessible only to the research team, adhering to ethical standards and protecting the participants’ privacy. The demographic profiles of the respondents, reflecting diversity in age, gender, education, income, and fast-food consumption frequency, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

3.2. Measures

This study used established scales on a five-point Likert scale to measure the variables. Sustainability communication was assessed with 5 items like, ‘The retail fast-food chains I patronize share information on social media about their efforts to reduce environmental impacts’. These items were based on the work by Tanford, et al. [61]. Fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility included 4 items such as, ‘I feel jointly responsible for the environmental impact caused by the retail fast-food chains I patronize’. These items were based on the work of Steg, et al. [62]. Felt obligation was measured with 4 items borrowed from Chen, et al. [63], which included the sample item ‘I feel an obligation to support eco-friendly fast-food services’. Eco-conscious behavior was assessed with 5 items including the sample item ‘I always choose menu options that have the least environmental impact’. These items were taken from Kautish and Sharma [64], which were originally based on the work of Roberts and Bacon [65]. Green value was measured with 4 items taken from Alagarsamy, et al. [66], with the sample item ‘It is important to me that the food and services I use do not harm the environment’. Full list of items is available in Appendix A.

To ensure data accuracy, both theoretical and empirical strategies minimized common method and social desirability biases. Anonymity was assured, survey items were neutrally worded, and question order was randomized. Empirically, Harman’s single-factor test showed a minimal common method bias [67,68], and variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis confirmed that all VIF values were below 3, indicating no significant multicollinearity. These steps ensured robust findings, enhancing this study’s validity and reliability.

4. Results

Our methodological approach for data analysis is grounded in well-established procedures commonly used in social science research to examine complex relationships among variables. We employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using the SMART-PLS software version 3.28, which is particularly suitable for exploratory studies that aim to develop theory and understand complex causal relationships [18,69,70]. PLS-SEM is widely recognized for its ability to handle complex models with multiple constructs and indicators while accommodating smaller sample sizes and non-normal data distributions [71,72]. Given the complexity of our model, which includes mediating and moderating variables, PLS-SEM was chosen to maximize explanatory power and assess both direct and indirect effects.

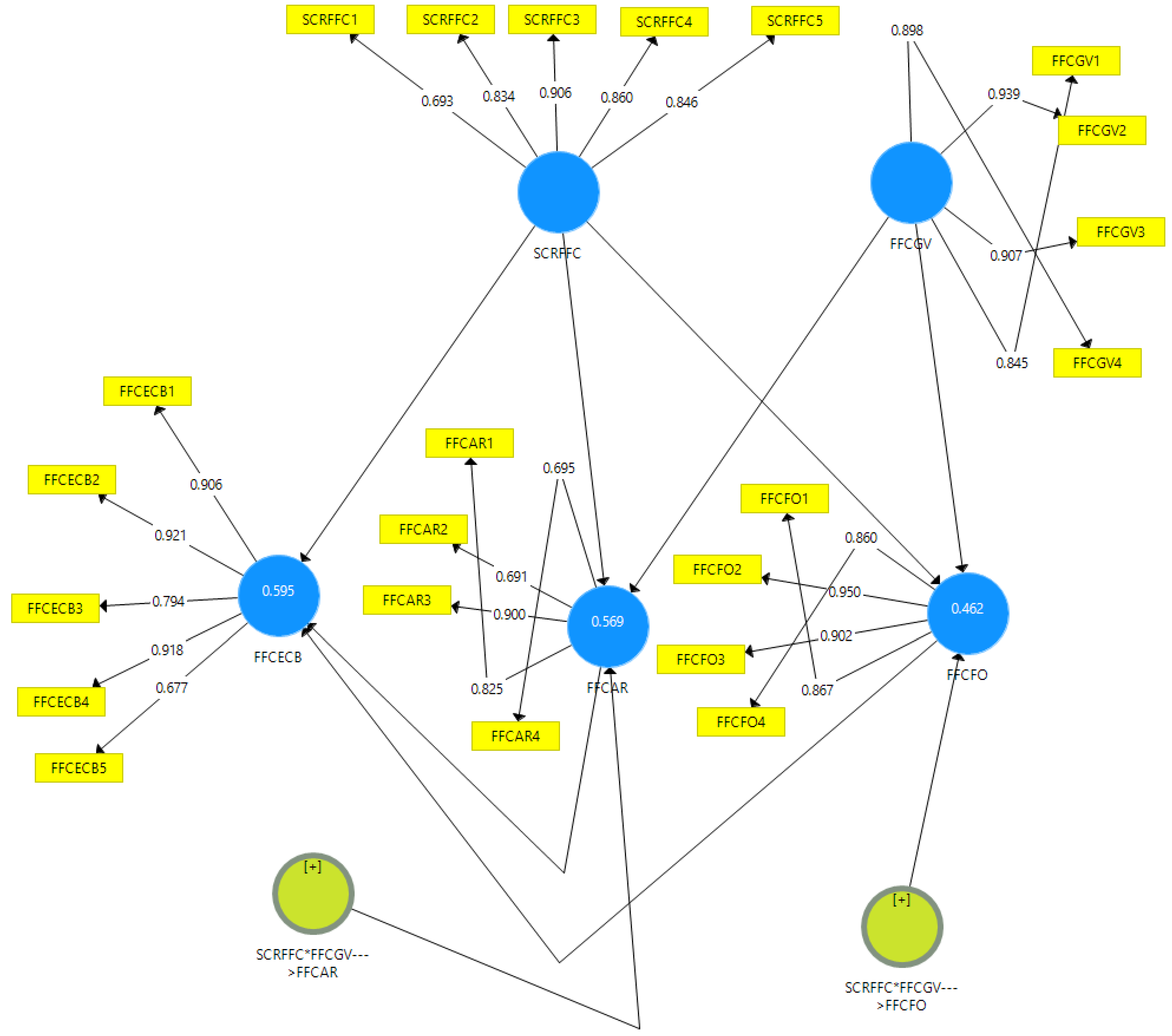

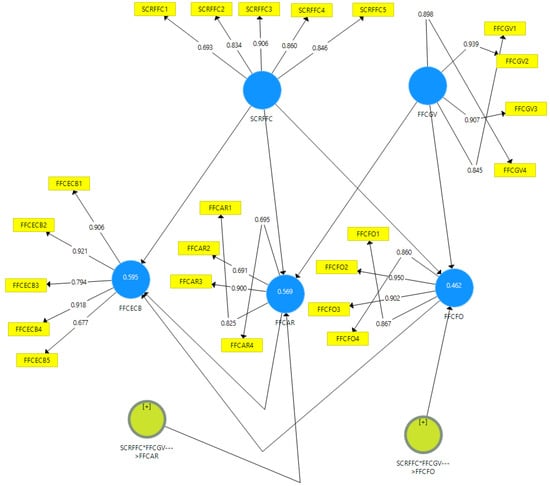

The data analysis results from SMART-PLS are summarized in Table 2, showing factor loadings, composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), and R Square values for the study’s constructs: fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (FFCAR), fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior (FFCECB), fast-food customers’ felt obligation (FFCFO), fast-food customers’ green value (FFCGV), and sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC). All factor loadings exceeded 0.60, ranging from 0.677 to 0.950, indicating strong associations with their constructs. Composite reliability values were above 0.70, confirming internal consistency [73,74,75], with FFCAR at 0.862, FFCECB at 0.927, FFCFO at 0.942, FFCGV at 0.943, and SCRFFC at 0.917. AVE values were all above 0.50, indicating good convergent validity. AVE ranged from 0.613 for FFCAR to 0.807 for FFCGV, with FFCECB and FFCFO at 0.720 and 0.801, respectively. R Square values showed that SCRFFC explained 51.2% of the variance in FFCAR (R2 = 0.512), 59.5% in FFCECB (R2 = 0.595), and 41.9% in FFCFO (R2 = 0.419), indicating moderate-to-substantial explanatory power, highlighting the impact of sustainability communication on customer responsibility, obligation, and eco-conscious behavior. Figure 2 represents our measurement model.

Table 2.

Data quality statistics of the measurement model.

Figure 2.

Measurement model showing the relationships between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC), fast-food customers’ green value (FFCGV), fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (FFCAR), fast-food customers’ felt obligation (FFCFO), and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior (FFCECB). The model includes factor loadings for each item and the R-square values for the endogenous constructs.

Table 3 shows the relationships between the variables. The square root of AVE values, listed diagonally, exceeds inter-construct correlations, confirming strong discriminant validity [76,77,78,79]. For example, the square root of AVE is 0.783 for FFCAR and 0.831 for SCRFFC, indicating distinct constructs. Correlations among constructs range from 0.355 to 0.558. SCRFFC shows significant correlations with FFCAR (0.468), FFCECB (0.558), and FFCFO (0.520), suggesting that sustainability communication positively impacts customer responsibility, obligation, and eco-conscious behavior. HTMT values, all below 0.90, further confirm discriminant validity. The highest HTMT is 0.869 between FFCAR and FFCECB, with others like 0.749 between FFCECB and FFCFO within acceptable limits. The f-squared values show that SCRFFC has a strong effect on FFCAR (f2 = 0.473) and a moderate effect on FFCFO (f2 = 0.314). SCRFFC’s effect on FFCECB is smaller (f2 = 0.042). FFCGV shows a moderate effect on FFCAR (f2 = 0.135) and FFCFO (f2 = 0.100), highlighting its role in shaping customer responsibility and obligation.

Table 3.

Correlations and discriminant validity.

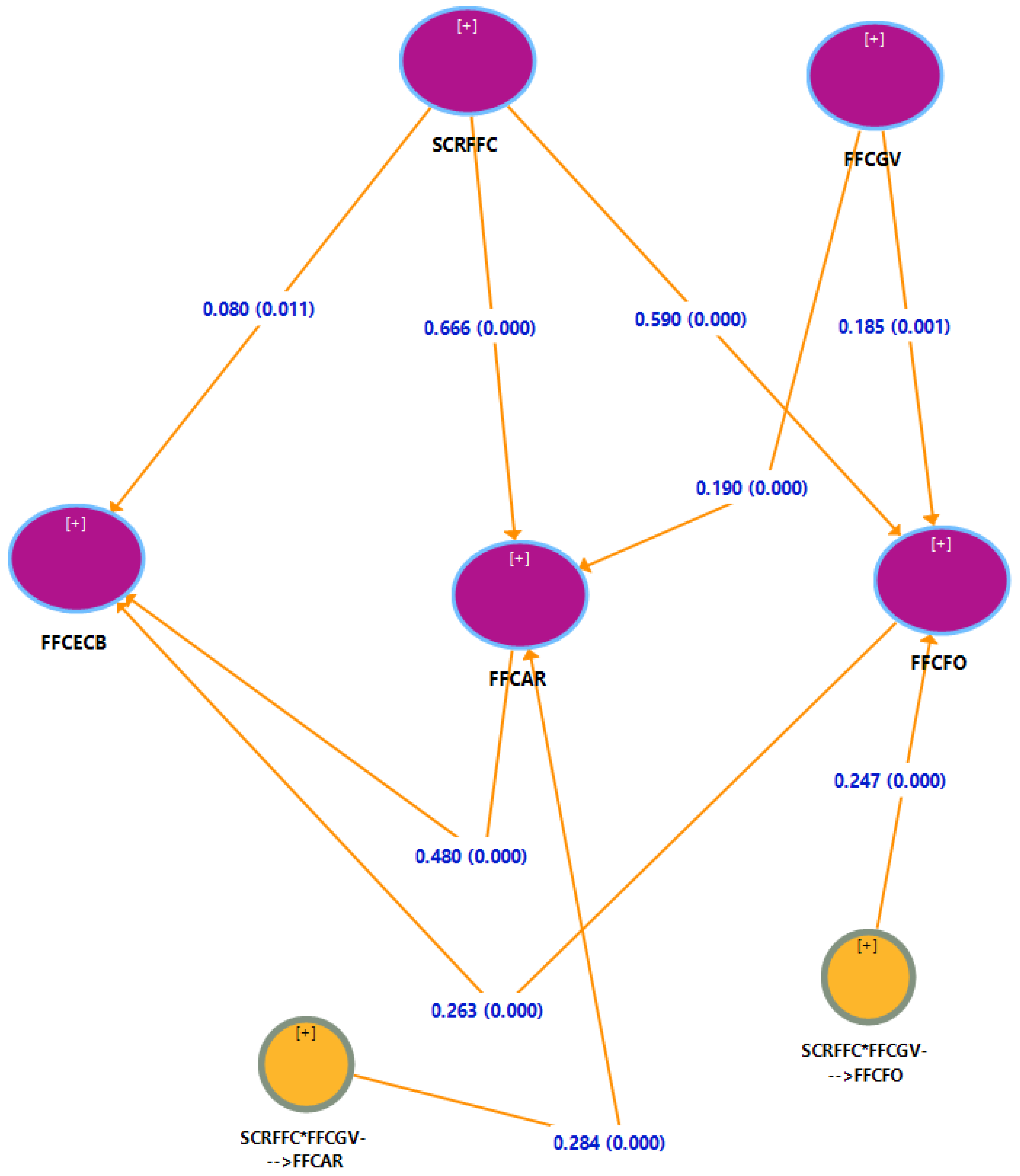

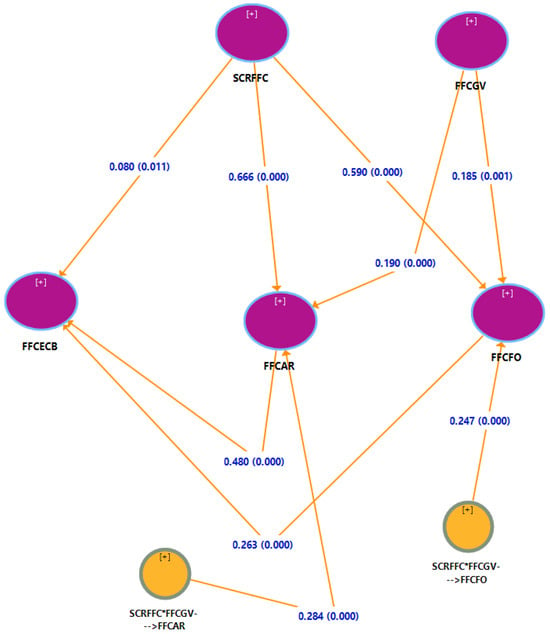

Table 4 summarizes the relationships among key constructs, confirming all the proposed hypotheses. Key findings include a modest positive impact of SCRFFC on FFCECB with a path coefficient of 0.08, t-statistic of 2.537, and p-value of 0.011, supporting H1. A stronger relationship exists between SCRFFC and FFCAR, with a path coefficient of 0.666, a t-statistic of 13.812, and a p-value of 0.000, confirming H2. FFCAR’s significant impact on FFCECB, with a path coefficient of 0.48, t-statistic of 8.794, and p-value of 0.000, supports H3, indicating that customers who feel responsible are more likely to engage in eco-conscious behavior. The mediation effect of FFCAR between SCRFFC and FFCECB (H4) is supported, with a path coefficient of 0.32, t-statistic of 8.123, and p-value of 0.000, emphasizing ascribed responsibility’s role in translating communication into action. The strong link between SCRFFC and FFCFO, with a path coefficient of 0.59, t-statistic of 10.3, and p-value of 0.000, validates H5, showing that communication fosters customer obligation. The direct impact of FFCFO on FFCECB (H6) is confirmed with a path coefficient of 0.263, t-statistic of 5.172, and p-value of 0.000, demonstrating that felt obligation drives eco-conscious behavior. The mediation effect of FFCFO between SCRFFC and FFCECB (H7) is also supported, with a path coefficient of 0.155, a t-statistic of 4.812, and a p-value of 0.000, confirming its key role.

Table 4.

Hypotheses summary.

The moderating role of FFCGV is confirmed in both mediation pathways. FFCGV strengthens the mediation of FFCAR on FFCECB (H8a, p = 0.000) and the mediation of FFCFO on FFCECB (H8b, p = 0.001). This highlights the importance of green values in enhancing sustainability communication through ascribed responsibility and felt obligation. Sustainability communication directly positively impacts eco-conscious behavior (H1), supporting Sunarya, et al. [32], who found that sustainability messages on social media boost consumer engagement and sustainable purchases. Psychological factors, ascribed responsibility, and felt obligation mediate this relationship (H4, H7), as Han, et al. [24] showed, indicating that perceived responsibility drives sustainable actions. Additionally, green values moderate the impact of sustainability communication (H8a, H8b), aligning with Shao, et al. [55], who demonstrated that green values enhance CSR message effectiveness. These findings suggest that fast-food companies should align their sustainability messages with consumers’ green values to increase effectiveness. The full structural model of the research is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural model illustrating the path relationships between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC), fast-food customers’ green values (FFCGV), fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (FFCAR), fast-food customers’ felt obligation (FFCFO), and fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behavior (FFCECB). The model includes path coefficients and p-values for each hypothesized relationship.

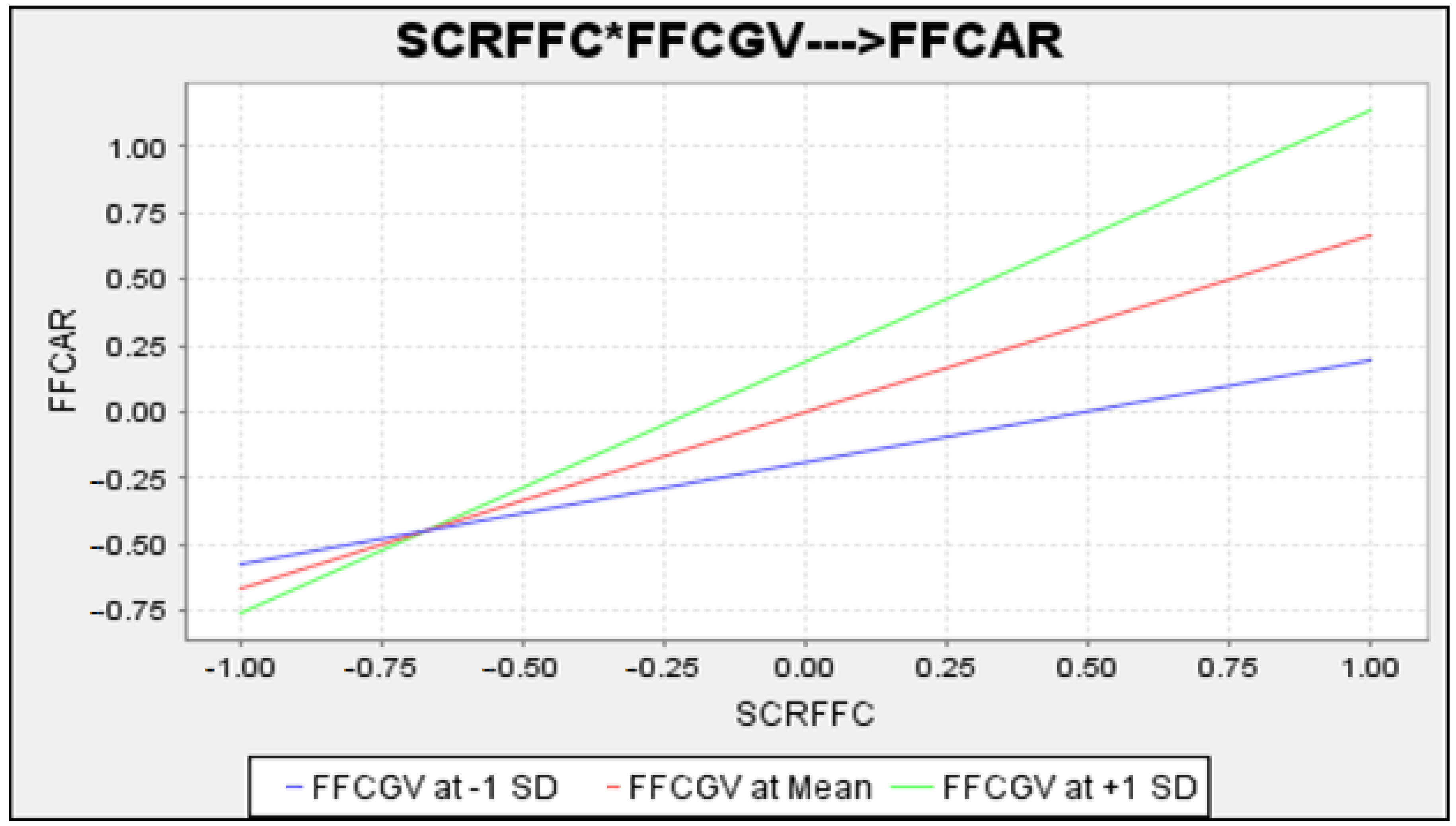

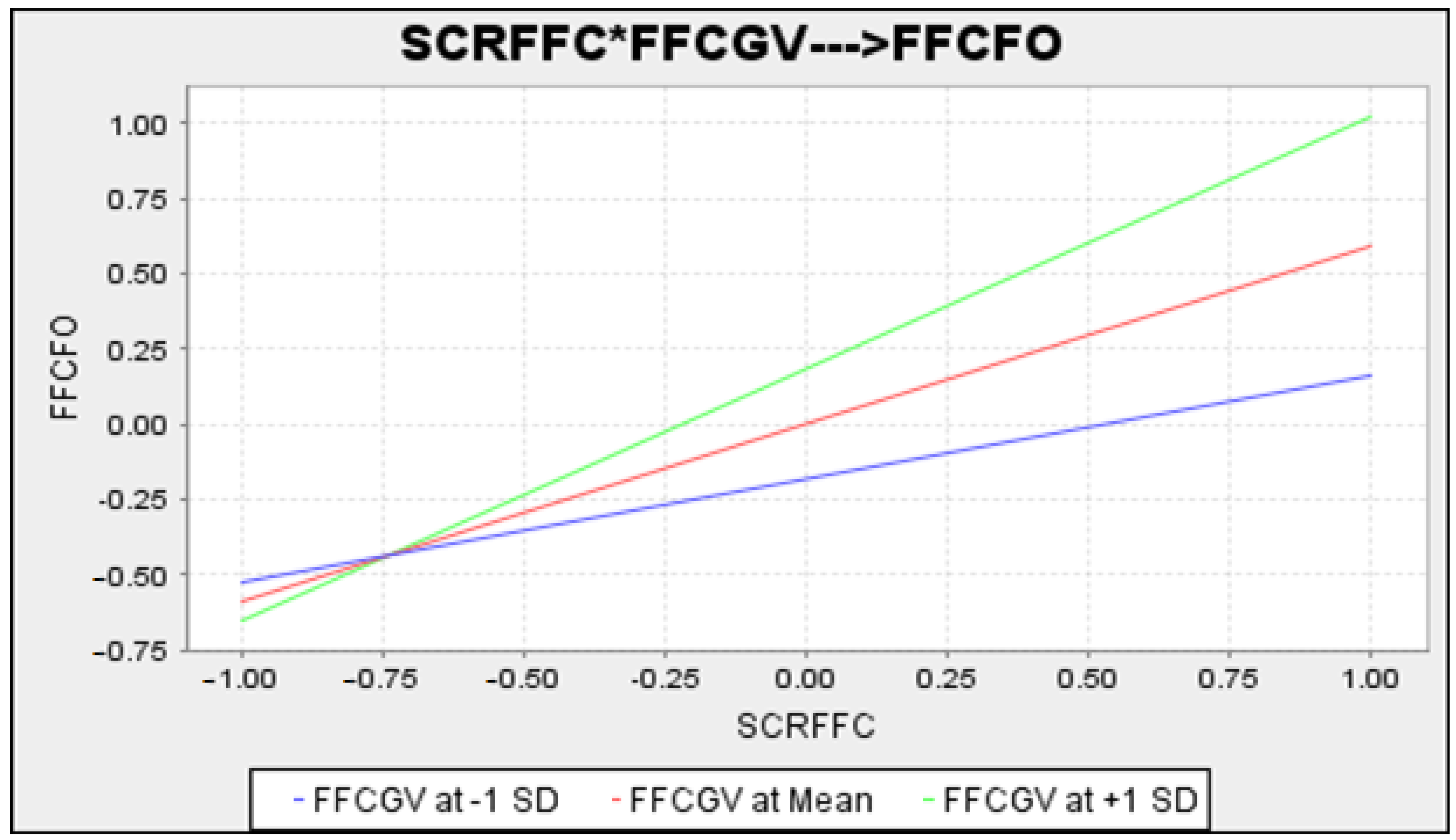

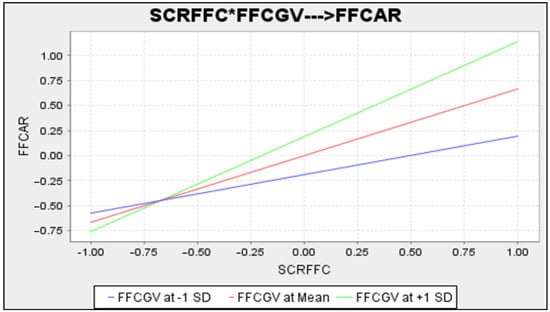

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate simple slope analysis for the moderation effect of FFCGV on the relationships between SCRFFC and both FFCAR and FFCFO. In Figure 3, the interaction between SCRFFC and FFCGV on FFCAR is depicted. The slopes show that as FFCGV increases (from −1 SD to +1 SD), the positive impact of SCRFFC on FFCAR strengthens. At higher levels of FFCGV (+1 SD), the slope is steepest, indicating that customers with stronger green values are more responsive to sustainability communication, leading to a greater sense of ascribed responsibility. Conversely, when FFCGV is low (−1 SD), the relationship between SCRFFC and FFCAR is weaker, suggesting that customers with lower green values are less influenced by sustainability communication in terms of feeling responsible.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of fast-food customers’ green values (FFCGV) on the relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC) and fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility (FFCAR).

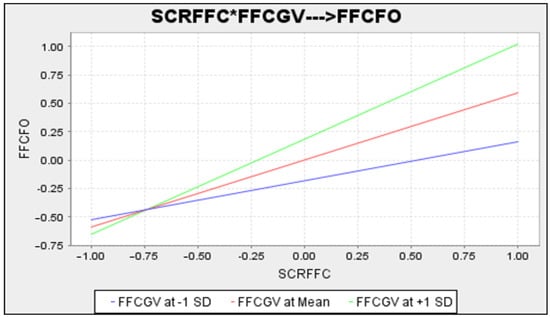

Figure 5.

Moderating effect of fast-food customers’ green values (FFCGV) on the relationship between sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains (SCRFFC) and fast-food customers’ felt obligation (FFCFO).

Similarly, Figure 4 illustrates the moderating effect of FFCGV on the relationship between SCRFFC and FFCFO. The pattern is consistent with that observed in Figure 3, where the slope increases as FFCGV rises. This indicates that the effect of SCRFFC on felt obligation is more pronounced among customers with higher green values. At +1 SD of FFCGV, the slope is steepest, showing that these customers are more likely to feel obligated to support sustainability efforts when exposed to sustainability communication. At lower levels of FFCGV (−1 SD), the impact of SCRFFC on FFCFO is weaker, reflecting a diminished sense of obligation among customers with lower environmental values.

5. Discussion

The results of this study have implications for sustainability communication and Malaysian consumer behavior in the fast-food sector. Overall, our study underlines the importance of sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains with regard to consumers’ attitudes and behaviors in terms of ascribed responsibility, felt obligation, and eco-consciousness. This is in line with prior research that posited that although sustainability communication affects customers’ eco-consciousness [39,80], other factors are also potent in determining fast-food customers’ eco-conscious behaviors. Our study also revealed a positive correlation between sustainability communication and fast-food customer-ascribed responsibility, further confirming the notion that better communication makes consumers more responsible for environmental impact [36,40]. The ascribed responsibility that affects eco-conscious behavior appears to be a significant mediator between sustainability communication and consumer behavior, thus supporting the findings of Chavez-Olivera, et al. [37] and Martínez-Sala, et al. [22] about the role of consumer responsibility in sustainable consumption.

In addition to this, the result of this study also provides evidence to support the hypothesis that sustainability communication has a significant relationship with fast-food customers’ felt obligation. This is in consonance with the contention that consumers who receive signals that a particular firm is concerned with sustainability will feel that it is morally right for them to support the firm’s cause [50]. The same as ascribed responsibility, felt obligation acts as a mediator between the reception of sustainability communication and real sustainable behaviors, which contributes to the comprehension of the psychological processes of consumers’ actions in relation to sustainability. Another factor is the fact that fast-food customers’ green values intervene between the impact of sustainability communication on ascribed responsibility and felt obligation. As in previous studies on the significance of personal values for consumer behavior [30], it is demonstrated that green values support the role of sustainability communication. Such evidence implies that sustainability communication should be appealing to consumers with concern for environmental sustainability. Green consumers are more likely to engage with the company’s messages; hence, they are more responsible and have perceived responsibility. This is in concord with other studies on values-based marketing that argue that when consumers are exposed to marketing communication messages, they are likely to pay attention if the messages contain values that are congruent with those of the consumer [53]. Drawing on signaling theory, our study highlights the role of sustainability communication in reducing information asymmetry between fast-food chains and Malaysian consumers. Firms use sustainability messages to influence consumer perceptions and behaviors concerning the environment. Our findings show that well-communicated sustainability initiatives signal trustworthiness, increasing consumer patronage, especially in fast-food markets where sustainability practices are not directly observable. Ascribed responsibility and felt obligation mediate how these signals lead to sustainable purchasing decisions. This research extends signaling theory by demonstrating its applicability to sustainability communication and consumer behavior in the fast-food industry, supporting the idea that effective communication fosters brand loyalty. This study contributes to understanding how sustainability communication in retail fast-food chains affects consumer behavior through ascribed responsibility, felt obligation, and green values. Sustainability communication directly predicts eco-conscious behavior, supported by mediating factors like ascribed responsibility and felt obligation, indicating that consumers internalize sustainability messages and feel responsible for environmental outcomes [43,44,81]. This enriches theoretical approaches to sustainability communication, aiding further research and practical applications in the fast-food sector.

Additionally, this research adds to knowledge on sustainability communication’s impact in Malaysia, an emerging economy with growing environmental awareness [27]. Despite environmental concerns like packaging waste and energy use in Malaysia’s fast-food industry, effective sustainability communication from fast-food chains increases consumers’ ascribed responsibility and felt obligation, enhancing their eco-consciousness. Moreover, green values significantly amplify these effects among consumers with strong environmental concerns, suggesting that fast-food chains in Malaysia should align sustainability messages with cultural norms and environmental values to promote sustainable consumer behavior.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Conclusively, the insights of this research provide a valuable theoretical contribution to the understanding of sustainability communication and consumer behavior, especially in the fast-food sector. Hence, our study contributes to the literature by applying the psychological factors of ascribed responsibility and felt obligation to show that sustainability communication has an indirect effect on fast-food consumers. The findings of this study negate the idea that sustainability communication is enough to foster environmentally sensitive behavior. Unlike previous research, which focuses on direct effects, this research indicates a more intricate relationship, based on different psychological mechanisms. In this study, ascribed responsibility and felt obligation are combined, and it is shown that these constructs are indeed crucial in bridging the communication gap between sustainability communications and eco-conscious behavioral change. This theoretical extension moves the discussion from the level of communication effectiveness to the level of cognitive and affective variables.

Our study also examines the moderating effects of green values, which present a theoretical framework that helps explain variability in reactions to sustainability communication. This study’s identification of green values as magnifying the effect of sustainability communication on both ascribed responsibility and felt obligation is a critical contribution to the literature, revealing the importance of value congruency in marketing communication. Apart from that, our study highlights the importance of social media in sustainability communication. The dynamic and two-way nature of social media allows for the sharing of sustainability messages and discussions with a large audience. This research contributes to the theoretical development of sustainability communication by identifying the role of social media in enhancing communication impacts, particularly for the green-consumption segment. In general, the theoretical contributions concern CSR and the consumer decision-making process. Hence, our research based on the fast-food industry, which is largely associated with negative impacts on the environment, gives a new insight into enhancing consumer attitudes and behaviors towards sustainability through better implementation of communication strategies and consumer psychology. This advances the CSR literature by demonstrating that, despite operating in a hostile environment, improvement in communication strategies leads to positive results.

This study supports and expands the existing knowledge on sustainability communication and consumer behavior. Consistent with Kong, et al. [9], it finds that sustainability communication positively influences sustainable consumption and further identifies ascribed responsibility and felt obligation as mediators, extending Han, et al. [24]’s work from airlines to fast food. Additionally, it contributes to Riva et al.’s [82] study by exploring environmental values as moderators. This comprehensive framework defines mediators and moderators of sustainability communication and consumer behavior, enhancing the theoretical understanding of behavior change mechanisms. Furthermore, this research enriches signaling theory by demonstrating that sustainability communication acts as credible signals that reduce information asymmetry and influence consumer behavior in the fast-food industry. Building on Chavez-Olivera, et al. [37], it reveals that these signals operate through psychological factors like ascribed responsibility and felt obligation, offering a nuanced perspective on how sustainability messages are decoded and acted upon by consumers.

5.2. Practical Implications

The practical implications of this research are relevant for the fast-food industry in Malaysia, particularly for enhancing sustainability initiatives and consumer engagement. Based on the extent to which fast-food chains’ sustainability communication influences consumers’ decision making, it is vital for firms to communicate sustainability efforts in a clear and coherent manner. This includes drawing attention to mitigation measures and stressing that everyone bears the responsibility of preserving the environment. Thus, fast-food chains can promote more environmentally friendly actions by increasing the perceived level of ascribed responsibility. One of the suggestions for fast-food chain organizations is to incorporate information on sustainability into other forms of communication such as social media. In our study, we have emphasized the contribution of social media in the sharing of sustainability information and interacting with customers. Businesses should leverage social media’s interactive nature to develop informative and engaging campaigns that can include customers in sustainability activities like the promotion of environmental causes or sustainable products such as environmentally friendly foods. It can be argued that this approach can enhance the effectiveness of sustainability communication among consumers with high green values.

The study therefore emphasizes the need to integrate sustainability communication with the consumer’s psychological motives, including perceived moral obligation and personal norms. This implies that fast-food companies should incorporate messages that appeal to the moral and ethical conscience of consumers. Targeted communication initiatives that deal with ethical obligations can encourage sustainable actions and actions on the part of the customer, strengthening the emotional connection. For example, when using real-life stories in marketing campaigns to illustrate why people have to adopt sustainable practices, the feeling of responsibility is improved. In addition, the awareness and legalization of sustainable practices should also be enhanced as well. This can be achieved by attaining certification from third-party agencies, partnership with environmental organizations, or reporting on sustainability performance measures. Providing information on the impact on the environment and initiatives in a factual and easily traceable manner is one of the factors that can become a key factor in building trust, which is important for creating long-term consumer loyalty and a positive brand image. Therefore, it can be concluded that fast-food chains have great potential to influence consumers’ behavior through sustainability communication. That is, change in companies’ behavior towards environmentally friendly products, differentiation from competitors, and the overall goal of environmental sustainability, alongside the enhancement of the company’s image, can increase customer loyalty.

From a practical point of view, it is important to appreciate the significance of sustainability communication as a means of signal credibility and communication consistency. According to this study, consumers prefer to engage with sustainability messages that they consider authentic and consistent with the overall brand image. From this, it can be inferred that fast-food chains should concentrate on the clear messaging of sustainability initiatives and messages across various platforms, especially social media, since consumers are active in these platforms. Furthermore, the implications of ascribed responsibility and felt obligation as mediators of the relationship indicate that companies need to develop messages that not only provide information but also make consumers feel that they also have a responsibility to perform an action. This means that appeals that involve public participation, for instance ‘let’s all reduce waste’ or ‘let’s all go green’, could be very influential in creating eco-consciousness. Finally, since green values influence consumers’ perceptions, fast-food chains should categorise their audience by environmental consciousness and use the right messages that appeal to the customer’s green values. For example, for eco-conscious consumers, additional information about particular sustainability efforts (for example, supply chain and packaging) may be more effective. For consumers who are not inclined towards the protection of the environment, more information-based campaigns that create awareness and then, over time, create a new culture of environmental conservation could be more effective. With such knowledge, fast-food chains are able to enhance the relevance of their sustainability communication strategies with regard to the psychology of consumers and, thus, promote longer-lasting positive behavioral changes.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the insights generated from this study on the effects of sustainability communication on Malaysian consumers’ behavior in the fast-food sector, this research has some limitations. First, this study uses cross-sectional data, which makes it difficult to establish causality between the variables. A longitudinal examination could provide more insight into how these associations change over time. Furthermore, this study is conducted within the context of the fast-food industry, and, thus, the results may not be applicable to other industries or geographical locations. Future research could investigate such dynamics in other industries or cultural contexts to increase the external validity and generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, it is important to note that there are other psychological or contextual factors that could be equally influential in determining the extent and nature of eco-conscious behavior and that are not addressed in this study, including consumer knowledge or peer pressure. Moreover, as the use of social media expands in the future, more research can be conducted on the features of social media platforms that are more effective in promoting sustainable consumer behaviors for a better understanding of efficient digital communication strategies.

6. Conclusions

This paper offers a systematic review of how sustainability communication by retail fast-food chains affects Malaysian consumers’ behavior through perceived ascribed responsibility and felt obligation, with green values as a moderator. This study shows that positive sustainability messages that are well articulated can make a huge difference in encouraging the customers of fast foods to be environmentally friendly if the messages are in tandem with the ethical and moral reasoning of the customers. By incorporating these psychological factors, this research goes beyond the simple direct effects of sustainability communication on behaviors and provides an understanding of the processes by which these effects occur. Practical implications include the suggestion that fast-food companies ought to ensure they have clear, coherent, and interesting sustainability communication that incorporates the use of social media and consumer values in the process of communicating about the sustainable practices that are expected from consumers. Although this study has its limitations, it presents several opportunities for further research, especially in understanding the sustained impact of sustainability communication across various industries and cultures. In conclusion, this study advances both the theoretical and practical knowledge of the fact that sustainability communication, if properly designed and delivered, can be a potent means of influencing consumers’ behavior. In conclusion, as the fast-food industry continues to learn ways of minimizing its effects on the environment, this research offers firms a guide on how to improve their sustainability and customer relationships.

Author Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing and editing of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project Number: 231106627223238, 2024 Ministry of Education Industry-University Co-operation Collaborative Education Project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Universiti Teknologi MARA Institutional Review Board (IRB), reference number UiTM-IRB-2023–1125, dated 25 November 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Items

| Construct | Items |

| Fast-Food Customer-Ascribed Responsibility | I feel jointly responsible for the environmental impact caused by the retail fast-food chains I patronize. |

| I feel jointly responsible for the depletion of natural resources due to the operations of the retail fast-food chains I frequent. | |

| I feel jointly responsible for the carbon footprint generated by the retail fast-food chains I choose. | |

| I believe my contribution to the environmental problems caused by retail fast-food services is negligible. | |

| Not only the government and industry are responsible for the high energy consumption levels in retail fast-food services, but I am too. | |

| I believe that individuals alone cannot significantly contribute to the reduction of environmental problems caused by retail fast-food services. | |

| Fast-Food Customers’ Green Value | It is important to me that the food and services I use do not harm the environment. |

| I consider the potential environmental impact of my choices when ordering from retail fast-food chains. | |

| My food preferences are influenced by my concern for the environment. | |

| I am concerned about wasting the natural resources involved in producing and delivering the food I consume. | |

| I would describe myself as an environmentally responsible fast-food customer. | |

| I am willing to be inconvenienced in order to choose options that are more environmentally friendly when dining at retail fast-food chains. | |

| Fast-Food Customers’ Felt Obligation | I feel an obligation to support eco-friendly retail fast-food services to help them achieve their sustainability goals. |

| I feel personally responsible for the success or failure of green initiatives at the retail fast-food chains I frequent. | |

| I feel a sense of obligation to participate in all aspects of sustainable practices at retail fast-food chains. | |

| I feel an obligation to ensure I choose high-quality, eco-friendly options from retail fast-food menus. | |

| I would feel an obligation to educate others about the benefits of eco-friendly retail fast-food services if required. | |

| I would feel guilty if I do not support green initiatives at retail fast-food chains. | |

| I feel that any obligation I must perform related to choosing eco-friendly options at retail fast-food chains is important. | |

| Sustainability Communication by Retail Fast-Food Chains | The retail fast-food chains I patronize disseminate information on social media regarding their efforts to reduce environmental impacts. |

| The retail fast-food chains I patronize support local communities through sustainable and responsible sourcing, as shared on social media. | |

| The retail fast-food chains I patronize promote sustainability in their food preparation and delivery processes on social media. | |

| The retail fast-food chains I patronize raise awareness on social media about the serious problem of food waste. | |

| The retail fast-food chains I patronize highlight their water conservation efforts in food preparation on social media. | |

| The retail fast-food chains I patronize emphasize the importance of energy efficiency in their operations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on social media. | |

| Fast-Food Customers’ Eco-conscious Behavior | When given a choice, I always choose menu options that contribute to the least amount of environmental impact. |

| I understand the potential damage to the environment that some food choices can cause, so I do not order those items. | |

| I have switched to more eco-friendly options at retail fast-food chains for ecological reasons. | |

| I have convinced some members of my family and friends not to order menu items that are harmful to the environment. | |

| When given a choice between two equal options, I always prefer the one which is less harmful to other people and the environment. |

References

- Emma, H.; Ben, V. European Heatwave: What’s Causing It and Is Climate Change to Blame? Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/news/european-heatwave-whats-causing-it-and-climate-change-blame (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Siddiqui, U. What Makes South Asia So Vulnerable to Climate Change? Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/7/8/what-makes-south-asia-so-vulnerable-to-climate-change (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Latapi, M.; Johannsdottir, L.; Davíðsdóttir, B. The energy company of the future: Drivers and characteristics for a responsible business framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Srivastava, R. Climate change and responsible business leadership. In Responsible Leadership for Sustainability in Uncertain Times: Social, Economic and Environmental Challenges for Sustainable Organizations; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven. J. Macromark. 2021, 41, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W. Unsustainable business models–Recognising and resolving institutionalised social and environmental harm. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; El-Manstrly, D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Ramayah, T. Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Naveed, R.T.; Scholz, M.; Irfan, M.; Usman, M.; Ahmad, I. CSR communication through social media: A litmus test for banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Nawaz, N.; Tripathi, A.; Muneer, S.; Ahmad, N. Using social media as a medium for CSR communication, to induce consumer–brand relationship in the banking sector of a developing economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, D.; Mendoza, C.M.T. Marketing Model of Starbucks: A Sustainability Monetization. J. Ekon. 2023, 12, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanses, B.; Jove, B.T.; Lukitasari, M.W. Public Relations Communication Strategies in Building Consumer Branding: Analysis of Unilever Company. Ilomata Int. J. Manag. 2024, 5, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, L.; Jha, H.; Sarkar, T.; Sarangi, P.K. Food waste utilization for reducing carbon footprints towards sustainable and cleaner environment: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald. Available online: https://corporate.mcdonalds.com/content/dam/sites/corp/nfl/pdf/McDonalds-2023-Climate-Resiliency-Summary.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Starbucks. Becoming Resource Positive. Available online: https://www.starbucks.com/responsibility/planet/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Yu, H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Han, H.; Scholz, M.; Sial, M.S. A contemporary issue of micro-foundation of CSR, employee pro-environmental behavior, and environmental performance toward energy saving, carbon emission reduction, and recycling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Mahmood, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Hernández-Perlines, F.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Scholz, M. Sustainable businesses speak to the heart of consumers: Looking at sustainability with a marketing lens to reap banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Han, H.; Kim, M. Elevated emotions, elevated ideas: The CSR-employee creativity nexus in hospitality. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mahmood, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Din, M.u.; Iqbal Khan, G.; Ullah, Z. Sustainability as a “new normal” for modern businesses: Are smes of pakistan ready to adopt it? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. Corporate social responsibility at the micro-level as a “new organizational value” for sustainability: Are females more aligned towards it? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sala, A.-M.; Quiles-Soler, M.-C.; Monserrat-Gauchi, J. Corporate Social Responsibility in the restaurant and fast food industry: A study of communication on healthy eating through social networks. Interface-Comun. Saúde Educ. 2021, 25, e200428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chi, X.; Kim, C.-S.; Ryu, H.B. Activators of airline customers’ sense of moral obligation to engage in pro-social behaviors: Impact of CSR in the Korean marketplace. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; AlDhaen, E.; Ullah, Z.; Scholz, P. Improving firm’s economic and environmental performance through the sustainable and innovative environment: Evidence from an emerging economy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 651394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, S.A.; Mahmood, A.; Saleem, S.; Ahmad, N.; Sharif, M.S.; Molnár, E. Proposing stewardship theory as an alternate to explain the relationship between CSR and Employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, C.S.; Hock, L.K.; Ying, C.Y.; Cheong, K.C.; Kuay, L.K.; Huey, T.C.; Baharudin, A.; Aziz, N.S.A. Is fast-food consumption a problem among adolescents in Malaysia? An analysis of the National School-Based Nutrition Survey, 2012. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globaldata. Malaysia Foodservice Market Size and Trends by Profit and Cost Sector Channels, Players and Forecast to 2027. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/malaysia-foodservice-market-analysis/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, A.; Lewandowska, A.; Han, H. From screen to service: How corporate social responsibility messages on social media shape hotel consumer advocacy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, A.; Siddique, I. Responsible tourism and hospitality: The intersection of altruistic values, human emotions, and corporate social responsibility. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarya, P.A.; Rahardja, U.; Chen, S.C.; Lic, Y.-M.; Hardini, M. Deciphering digital social dynamics: A comparative study of logistic regression and random forest in predicting e-commerce customer behavior. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2024, 5, 100–113. [Google Scholar]

- Singha, S. Engaging Audiences: Leveraging Social Media for Sustainable Brand Narratives. In Compelling Storytelling Narratives for Sustainable Branding; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Enke, N.; Borchers, N.S. Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. In Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2021; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Waris, I.; Amin ul Haq, M. Predicting eco-conscious consumer behavior using theory of planned behavior in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 15535–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in society 5.0 idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Olivera, D.; Guerrero-Tirado, F.; Cordova-Buiza, F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior: A Correlation in the Fast-Food Industry. In Technology-Driven Business Innovation: Unleashing the Digital Advantage: Volume 2; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Alrousan, M.K.; Yaseen, H.; Alkufahy, A.M.; Alsoud, M. Boosting online purchase intention in high-uncertainty-avoidance societies: A signaling theory approach. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Chen, S.-C.; Wiangin, U.; Ma, Y.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Customer behavior as an outcome of social media marketing: The role of social media marketing activity and customer experience. Sustainability 2020, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.F.; Shahzad, M.F. Fast-food addiction and anti-consumption behaviour: The moderating role of consumer social responsibility. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Sustain. Consum. Behav. Environ. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.; Jiang, Y. Effectiveness of sustainability communication on social media: Role of message appeal and message source. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 949–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived environmental responsibilities and green buying behavior: The mediating effect of attitude. Sustainability 2020, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yang, Z. The impact of moral identity on consumers’ green consumption tendency: The role of perceived responsibility for environmental damage. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Shehata, H.S.; Mahmoud, H.M.E.; Albakhit, A.I.; Almakhayitah, M.Y. The effect of environmentally sustainable practices on customer citizenship behavior in eco-friendly hotels: Does the green perceived value matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; He, C.; Hu, T.; Jiang, T. Integrating values, ascribed responsibility and environmental concern to predict customers’ intention to visit green hotels: The mediating role of personal norm. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1340491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumi, A.; Obal, M.; Yang, Y. Investigating social media as a firm’s signaling strategy through an IPO. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aflak, A.; Vij, P. Going Green: The Effects of Moral Obligation and Social Media on Green Purchase Intention. In Sustainability Development through Green Economics; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ahmad, N.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H. Social ripple: Unraveling the impact of customer relationship management via social media on consumer emotions and behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2023, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive sustainability model based on the theory of planned behavior incorporating ecological conscience and moral obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. The impacts of perceived moral obligation and sustainability self-identity on sustainability development: A theory of planned behavior purchase intention model of sustainability-labeled coffee and the moderating effect of climate change skepticism. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2404–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, A.; Prybutok, G.; Prybutok, V.R. Insights into the antecedents of fast-food purchase intention and the relative positioning of quality. Qual. Manag. J. 2018, 25, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Samad, S.; Han, H. Travel and tourism marketing in the age of the conscious tourists: A study on CSR and tourist brand advocacy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alniacik, E.; Moumen, C.; Alniacik, U. The moderating role of personal value orientation on the links between perceived corporate social performance and purchase intentions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2724–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Mahmood, A.; Han, H. Unleashing the potential role of CSR and altruistic values to foster pro-environmental behavior by hotel employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trang, H.L.T.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. How do green attributes elicit pro-environmental behaviors in guests? The case of green hotels in Vietnam. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.; Wilson, J. I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, A.; Siddique, I. Beyond self-interest: How altruistic values and human emotions drive brand advocacy in hospitality consumers through corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2439–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Samad, S.; Comite, U.; Ahmad, N.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ energy-specific pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from healthcare sector of a developing economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mohammad, S.J.; Nawaz, N.; Samad, S.; Ahmad, N.; Comite, U. The role of CSR for de-carbonization of hospitality sector through employees: A leadership perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, E.J. Priming social media and framing cause-related marketing to promote sustainable hotel choice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1762–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Matloob, S.; Sunlei, Y.; Qalati, S.A.; Raza, A.; Limón, M.L.S. A moderated–mediated model for eco-conscious consumer behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior and environmentally conscious consumer behavior: An empirical investigation from emerging market. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Bacon, D.R. Exploring the subtle relationships between environmental concern and ecologically conscious consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagarsamy, S.; Mehrolia, S.; Mathew, S. How green consumption value affects green consumer behaviour: The mediating role of consumer attitudes towards sustainable food logistics practices. Vision 2021, 25, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Ahmad, N.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H. Triple-E effect: Corporate ethical responsibility, ethical values, and employee emotions in the healthcare sector. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2023, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H. From boardroom to breakroom: Corporate social responsibility, happiness, green self-efficacy, and altruistic values shape sustainable behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2024, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Samad, S.; Mahmood, S. Sustainable pathways: The intersection of CSR, hospitality and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]