Abstract

Over the past three decades, global tourism has significantly contributed to the world economy, driven by factors such as globalization, technological advancements, and rising disposable incomes. However, alongside these economic benefits, tourism’s environmental impact remains a pressing concern, involving resource depletion, pollution, and substantial carbon emissions. Despite extensive research on these issues, there remains a gap in the literature regarding how state social responsibility and sustainability can be effectively integrated into tourism policies, particularly in prominent tourist destinations like Spain. This study addresses this gap by employing a combined qualitative (content analysis) and quantitative (survey) approach to explore the dual role of tourism in economic growth and environmental sustainability. Focusing on Spain as a case study, the research highlights both the challenges and opportunities associated with sustainable tourism practices. It examines the influence of factors such as the host country’s image, quality of life, the home country’s purchasing power parity (PPP), and the geographical distance between home and host countries on tourists’ destination choices within the framework of Stakeholder Theory. The novelty of this research lies in its comprehensive analysis of these factors, offering critical insights for researchers and policymakers striving to balance tourism growth with environmental sustainability globally.

1. Introduction

Over the past 30 years, the contribution of tourism to global GDP has steadily increased. Factors such as globalization, technological advancements, and rising disposable incomes have fueled growth in international travel and tourism expenditures. Specifically, the tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP in 2023, marking a 23.2% increase from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 pre-COVID level. Additionally, in 2023, the tourism industry created 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level [1]. However, tourism is also a significant contributor to global environmental change, posing the challenge of meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs [2].

Specifically, the negative environmental impacts of tourism are substantial, including the depletion of local natural resources, pollution, and waste problems. For instance, tourism is responsible for approximately 8% of the world’s carbon emissions [3]. An average golf course in a tropical country serves as another example, using as much water as 60,000 rural villagers and applying 1500 kg of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides annually [4]. This is particularly significant given that international tourist arrivals increased from 25 million in 1950 to 166 million in 1970, 435 million in 1990, and 1.442 billion by 2018. International tourism reached 88% of pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2023 [5]. In the specific case of Spain, the arrival of tourists in 2023 surpassed the pre-pandemic level with a new record of 85 million visitors, which represents an 18.7% increase compared to 2022 and is 1.9% above 2019, the reference year before the pandemic [6].

To mitigate the negative effects of tourism, the UN Tourism Organization (UNWTO) designated 2017 as the year of sustainable tourism, aligning with the UN’s sustainable development goals, specifically through the UNWTO Journey to 2030 initiative. This led to several guidelines for the future development of sustainable tourism [7]. More recently, the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) emphasized in 2021 that sustainability should be central to all future policies to ensure a revival that benefits both people and the planet [8]. These initiatives have attracted significant academic interest in tourism sustainability [9].

Academic concern about the negative effects of tourism began in the 1960s, but it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that sustainability became integrated into the economic and political structures of tourism [10]. Alongside this shift, consumer preferences have increasingly leaned towards sustainable tourism options, driven by heightened awareness of climate and environmental issues [11]. Tourists are therefore more inclined to choose destinations and services that align with their environmental values, such as eco-friendly accommodations and responsible travel practices [12]. This shift in consumer behavior underscores the need for the tourism industry to adopt more sustainable practices, as consumer demand for sustainability can be a powerful driver of change.

This paper makes an important contribution to the literature by investigating the impact of sustainability initiatives on tourist behavior in one of the world’s most visited countries, Spain. While many studies have examined the environmental impacts of tourism or consumer preferences for sustainable tourism in isolation, this study combines these perspectives to explore how national sustainability policies and social responsibility initiatives affect international tourists’ intentions to visit Spain. This focus on Spain is particularly relevant given its significant influence on global tourism trends and its potential to serve as a model for sustainable tourism practices worldwide.

In response to this evolving landscape, further research is essential to explore how sustainability can be effectively integrated into tourism policies and practices, particularly in high-impact destinations like Spain [2]. The aim of this study is to assess the impact of Spain’s sustainability initiatives on international tourist behavior, examining the roles of social responsibility, country image, quality of life, and other factors in shaping tourists’ decisions. Spain, as one of the leading tourism destinations globally, is crucial for studying sustainability because the country’s tourism industry significantly influences both the global tourism market and environmental impact. With such a large number of visitors annually, any sustainability initiatives implemented in Spain could serve as a model for other tourism-dependent countries, making the study of this region both relevant and urgent.

This paper, therefore, aims to examine the impact of sustainable and socially responsible initiatives undertaken by Spain on international tourists’ intentions to visit the country. Spain was selected as the focus of this study not only due to its prominence in the global tourism industry but also because it faces unique challenges and opportunities in balancing economic benefits with environmental responsibilities. Spain is the second most visited country in the world, closely following France [13]. Moreover, since 2015, Spain has consistently ranked in the top three (second position) on the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index, which evaluates the most competitive countries in the tourism industry among 119 economies. Spain also boasts the highest number of Biosphere Reserves designated by UNESCO, with 53 Natural Areas and Natural Spaces, followed by the United States, Russia, and China [14]. This makes Spain an ideal case study for assessing how sustainability can be integrated into tourism practices in a highly competitive and ecologically diverse context. Not surprisingly, tourism is a major driver of the Spanish economy, generating over 2.6 million jobs, accounting for 12.8% of the country’s total employment, and contributing 12.3% to its GDP [15].

In addition to examining the influence of state social responsibility (SSR) and sustainability engagement, this paper explores the impact of a country’s image and quality of life on tourists’ destination choices. Specifically, the research seeks to answer how sustainable and socially responsible initiatives affect tourists’ decisions to visit Spain, as well as the roles that the host country’s image, quality of life, the home country’s purchasing power parity (PPP), and the geographical distance between home and host countries play in tourists’ decision-making processes. To address these research questions, the study draws on Stakeholder Theory [16], a framework widely applied in the literature on CSR and sustainability management in tourism [10,11,12]. This theoretical approach allows for an examination of how various stakeholders in the tourism industry, including governments, businesses, and tourists, can contribute to and benefit from sustainable tourism practices.

The upcoming sections of the paper will cover a review of existing literature and the formulation of research hypotheses. This will be followed by an explanation of the methodology, an analysis of the results, and a discussion of the findings. The conclusion will outline the scholarly and practical contributions of the study, highlight its main limitations, and offer recommendations for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Formulation

Among the diverse theoretical frameworks used in environmental and sustainability management research, Stakeholder Theory stands out as a prominent and frequently applied approach [17]. This theory focuses on the intricate relationships between businesses and their stakeholders, which include customers, suppliers, employees, investors, and other interested parties. It contends that companies should generate value for all stakeholders, not just prioritize shareholders [16]. At its core, Stakeholder Theory advocates for ethical and responsible behavior towards all stakeholders, suggesting that such practices enhance overall business success [18].

Within this framework, a company is viewed as a complex network of relationships among various individuals or groups. These stakeholders provide resources, shape the business environment, and impact the operational efficiency of the company [19]. On the other hand, the potential loss of support from any stakeholder is seen as a critical threat to a business’s survival [20]. Accordingly, Stakeholder Theory provides a holistic perspective that aligns with the evolving expectations of consumers and investors [21].

In today’s interconnected world, stakeholders are increasingly concerned about corporate practices regarding environmental conservation, social responsibility, and ethical governance [12]. As consumer preferences increasingly shift towards sustainability, driven by heightened environmental awareness and global events like the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses that incorporate social initiatives and sustainable practices not only enhance their reputation but also gain a competitive edge by appealing to customers and investors who prioritize ethical and environmentally responsible behavior [22]. This comprehensive perspective makes Stakeholder Theory particularly relevant in the context of social responsibility and sustainability in general [23], and to the tourism sector in particular [24].

More specifically, sustainable tourism development has gradually become an essential factor for destinations seeking long-term competitive advantage and resilience [25]. For instance, the pandemic has heightened consumer demand for safe and environmentally friendly travel options, significantly influencing destination choices worldwide [11]. Tourists are increasingly favoring destinations that prioritize environmental conservation and social responsibility, reflecting a broader shift towards sustainability in travel behavior. Within this scenario, Stakeholder Theory underscores the importance of preserving natural and cultural resources and considering the interests of various groups, such as local communities and environmental organizations. By doing so, tourism destinations can foster mutual trust and cooperation, reflecting a growing awareness and preference among tourists for environmentally and socially responsible travel destinations [10].

In addition, the literature suggests that sustainability initiatives can provide a competitive advantage. For instance, Porter and Kramer (2011) argued that companies that incorporate shared value into their strategy can achieve both social impact and economic benefits. Similarly, Zhu, Liu, and Lai (2016) found that businesses engaging in social responsibility initiatives not only enhance their reputation but also improve their competitive position in the market. However, recent literature has noted that the impact of sustainability initiatives on business success can be contingent on various factors, such as customer preferences and market conditions [26].

In summary, Stakeholder Theory is one of the most extensively studied frameworks in sustainable business management and social issues. It provides a foundational perspective for integrating social and sustainable practices within the tourism industry [24]. Through this approach, destinations can not only enhance their performance and reputation but also foster mutual trust and cooperation, contributing to the well-being of communities and ecosystems. This aligns with the growing awareness and preference among tourists for environmentally and socially responsible travel destinations [25]. This comprehensive perspective then makes Stakeholder Theory particularly relevant in the context of social responsibility and sustainability within the tourism sector.

The Adoption of Sustainable and Social Initiatives as Drivers of International Tourists’ Country Choice

Social responsibility is defined as a business’s contribution to sustainable economic development [27], focusing on fulfilling societal needs while safeguarding the well-being of future generations [28]. Consequently, institutions have obligations towards the communities and environments in which they function [29]. These obligations form an implicit agreement with society, often referred to as the social contract [30].

In the context of international tourism, integrating sustainable practices and social initiatives requires addressing both environmental and social concerns, and aligning these efforts with the interests of diverse stakeholders. These stakeholders include local communities (primarily residents and local businesses), visitors, government and public sector institutions, the tourism industry and related private sector companies, NGOs, and educational and research institutions, as well as investors and financial institutions. Among these stakeholders, tourists are recognized as primary stakeholders [31], due to their significant influence on a destination’s reputation and attractiveness [32]. Consequently, countries that adopt and enforce social and sustainable practices gain a competitive edge in the global tourism market [24], and attract tourists who are increasingly aware of social and sustainability issues.

Regarding consumer preferences and their evolution, a significant shift towards sustainability and social responsibility has been observed in the literature, accelerated by global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. This crisis has heightened awareness and altered travel behaviors, with an increasing number of tourists prioritizing destinations that align with their values of sustainability and social responsibility [34].

Globally, this shift is especially noticeable in Europe, where travelers are increasingly looking for destinations that align with their environmental and ethical values. In addition to factors such as travel expenses and other socio-economic conditions [35], European tourists now prioritize destinations that implement eco-friendly practices and contribute positively to local communities [36]. This trend is further reinforced by the broader context of changing consumer values and preferences in response to socio-economic challenges [37]. Adapting to these evolving preferences is essential for attracting tourists interested in responsible travel options, thereby gaining a competitive edge in the global tourism market [38].

It should also be noted that countries addressing societal needs and sustainability not only fulfill the social contract but are also positioned to benefit from it, aligning with the inherent nature of this agreement [39]. This differentiation makes them more attractive to international tourists who seek responsible travel options [40]. It also helps destinations gain a competitive edge in the global tourism market [12], aligning with the Stakeholder Theory postulates that long-term success is achieved by setting organizational practices with stakeholder expectations and societal norms [25].

It should also be noted that countries addressing societal needs and sustainability not only fulfill the social contract but are also positioned to benefit from it, aligning with the inherent nature of this agreement [39]. This differentiation makes them more attractive to international tourists who seek responsible travel options. However, it is important to acknowledge that while sustainability initiatives can increase a destination’s appeal, their impact on tourist decisions may vary depending on other factors, such as price competitiveness and alternative offerings [26].

In conclusion, by aligning tourism practices with broader social and environmental standards, the mutual interests of all parties involved are achieved [41]. This enhances the destination’s positioning and ensures long-term success in the industry [18], becoming a competitive advantage among the growing market segment of environmentally and socially conscious travelers [42].

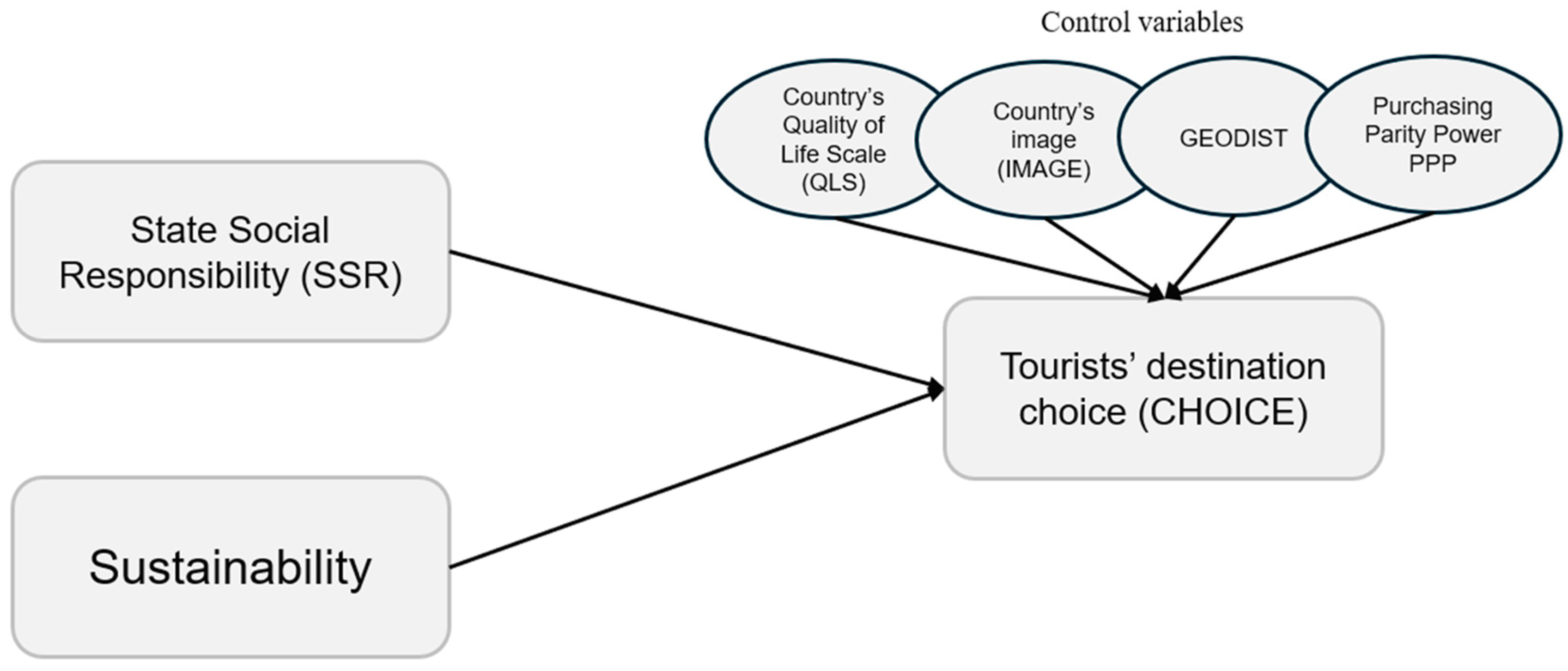

Based on the above arguments, we propose that the integration of sustainable and social programs positively influences tourists’ intentions to visit a destination, as reflected in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of tourist destination choice leveraged on the concept of sustainability.

Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

The implementation of social initiatives by a country is positively related to tourists’ willingness to visit the destination.

H2.

The implementation of sustainable practices by a country is positively related to tourists’ willingness to visit the destination.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a dual-method approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative techniques. The qualitative component involves content analysis to gather information about Spain as a preferred tourism destination and the social and sustainable initiatives implemented in the country. To achieve this goal, alongside academic literature, professional and managerial reports such as the UN Tourism Report, the WTTC Economic Report, the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI), the McKinsey & Company Sustainability Report, and the Booking.com Sustainable Travel Research Report were considered, among others. This initial step is chosen for its reliability and the frequent updates it provides [43]. Moreover, the usefulness of content analysis as a research tool is widely recognized in recent literature as a research tool that allows a thorough examination of social and sustainability objectives [28,44].

The quantitative part (survey) consists of an online survey through a Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) methodology based on consumer panel data provided by the GFK Global Research Company. This approach is chosen for its cost-efficiency and the capability to access a large, diverse sample across various geographic locations, particularly targeting individuals who use social media platforms and company websites.

While we acknowledge the limitation of relying solely on online surveys, which may introduce sample bias—particularly by underrepresenting older individuals or those less familiar with the internet—we justify this choice based on the following considerations: Firstly, the target audience for this study primarily comprises younger individuals who are more likely to engage with digital platforms, aligning with current tourism trends. This demographic is especially relevant given the focus on sustainable and socially responsible tourism practices among younger travelers. Secondly, to address potential biases, we employed stratified multistage sampling with proportional allocation and quotas to ensure representation by sex and age.

3.1. Eligibility of Spain

Spain is the second most visited country in the world after France and the second in tourist expenditures after the United States. As stated by the Spanish Minister for Industry and Tourism, Jordi Hereu, at the 2024 FITUR (Feria Internacional del Turismo—International Tourism Trade Fair), Spain is a world leader in tourism, hosting over 85 million international tourists and generating 108 billion euros in spending in 2023. This data indicates that Spain exceeded the number of tourists in the pre-pandemic reference year of 2019 by 1.9% and spending from the same year by 18.7% [6].

Additionally, Spain has developed a Sustainable Tourism Strategy 2030, a national agenda to help the tourism sector address medium- and long-term challenges, including socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. It should also be noted that according to the Greenview Hotel Footprinting Tool, which calculates the carbon footprint of a hotel stay anywhere in the world, Spain is among the best-performing countries in terms of low-carbon room footprint and meeting footprint [45]. This highlights Spain’s growing commitment to environmental issues.

Consequently, Spain’s outstanding position and relevance in international tourism justify its selection for this study.

3.2. Data Collection

As previously mentioned, the authors first conducted a content analysis of professional and academic journals, along with managerial reports, to identify Spain’s corporate social responsibility and sustainability efforts and assess their influence on tourists’ destination choices. This methodology is consistent with recent studies on sustainable tourism (Kwon and Lee, 2021 [12,46]. Following this, the research hypotheses were evaluated through an analysis of an online survey carried out in 2023 by GfK, a leading global research corporation, commissioned by the Foro de Marcas Renombradas Españolas [Spanish Forum of Well-known Brands] and financially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Industry and Tourism. The questionnaire and field research had a broader global scope that exceeded the main objectives of this paper, analyzing the image of Spanish brands and the country brand in various dimensions, including Spain as a tourist destination brand.

Six countries were selected for the research: China, France, Germany, Mexico, the USA, and the UK. The selection criteria were multifaceted, considering factors such as export–import trade flows, inward and outward investment flows, and tourism flows. These criteria were chosen to ensure that the sample represented key markets across three different continents, providing a comprehensive view of Spain’s international tourism appeal. While other European countries, such as Italy or the Netherlands, send more tourists to Spain than Mexico, the United States, or China, the three selected European countries—France, Germany, and the UK—are among the most significant in terms of economic and tourism relationships with Spain.

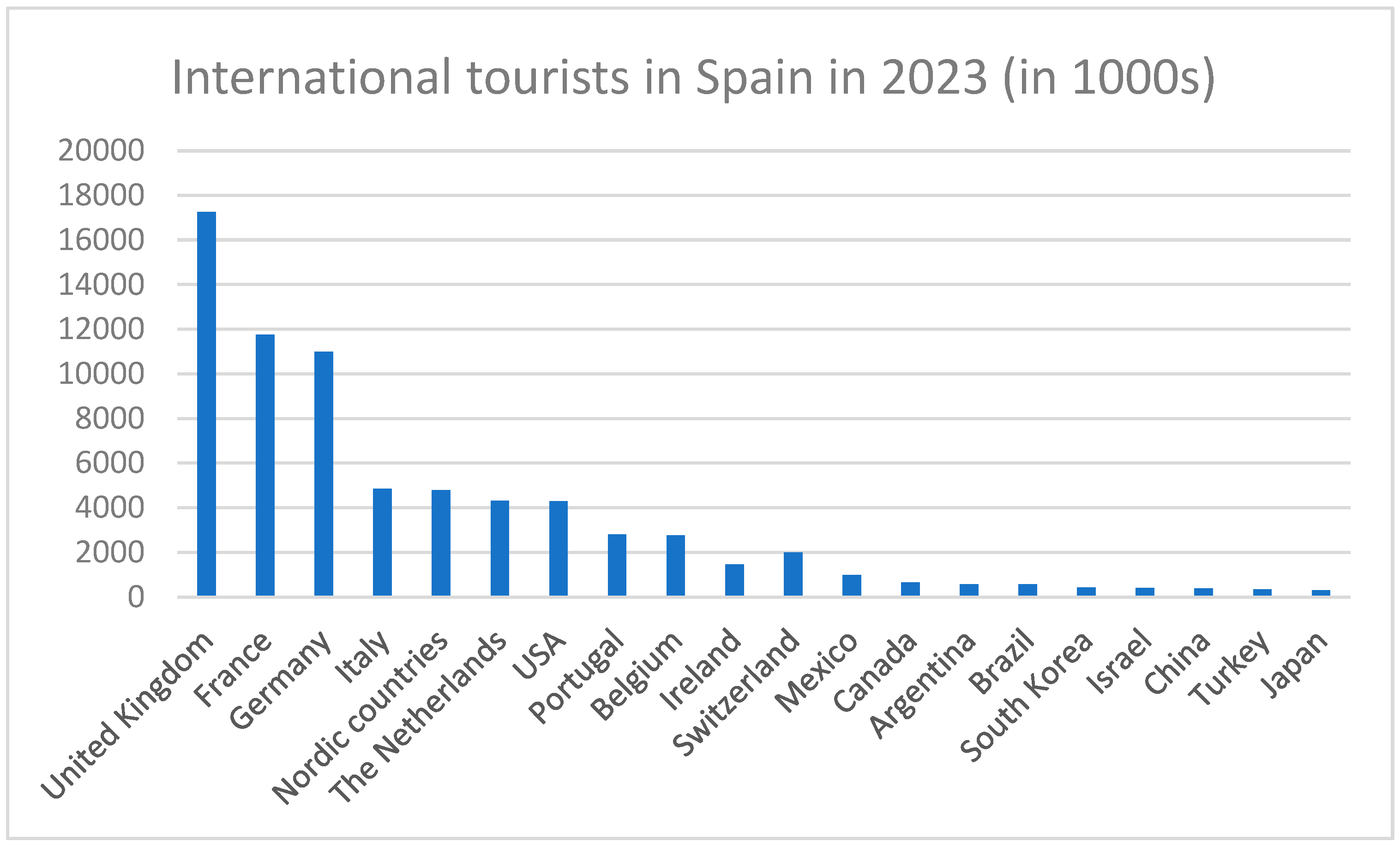

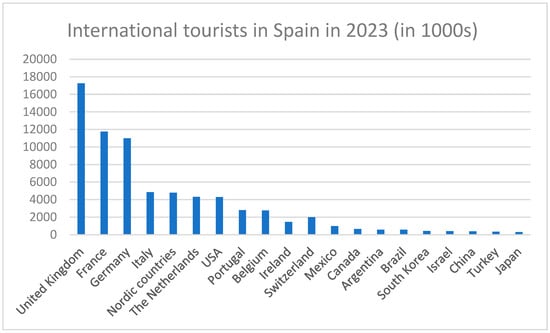

This selection also allows for the inclusion of major non-European markets within the budgetary constraints of the study. Specifically, China was included due to its rapid growth in outbound tourism and its increasing importance as a source market for Spain. Among the nearly 85 million international tourists that Spain received in 2023, the countries selected for this study—representing Europe, America, and Asia—contributed significantly to Spain’s tourism sector. Figure 2 shows that the United Kingdom (17,262,000 visitors), France (11,768,000 visitors), Germany (10,989,000 visitors), the USA (4,285,000 visitors), Mexico (984,000 visitors), and China (388,000 visitors) collectively accounted for more than 65% of all international tourists. This substantial contribution justifies the inclusion of these countries in our study, as they represent the primary source markets for Spain across the globe.

Figure 2.

Top 20 numbers of international tourists in Spain in 2023 by country of residence (in 1000 s). Source: Own elaboration based on Statista (2024).

Using the GfK Consumer Panel, the aim was to obtain a sample of 1000 individuals aged 18 and over per country, ensuring a sampling error below +/−3% (with a 95% confidence level and p = q = 0.50). A stratified multistage sampling with proportional allocation was employed. In the first stage, the sample was stratified by countries, each with a quota of 1000 individuals. In the second stage, a simple randomization was performed on the universe of internet users based on the GfK global panel. Quotas were added to avoid bias, ensuring representation by sex and age. Fieldwork was conducted between 6 and 22 November 2023. The questionnaire had an average duration of 12 min.

- (A)

- Measurement of the Dependent and Independent Variables

The survey utilized a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”), to gauge the influence of dependent and independent variables, as shown in Table 1. A total of 6000 completed questionnaires were obtained for this study, with 1000 respondents from each of the six countries considered (France, Germany, United Kingdom, USA, China, and Mexico). Regarding age, 58% of the respondents were between 18 and 34 years old, 31.3% were between 35 and 54 years old, and the remaining 10.7% were over 55 years old. In terms of gender distribution, 51.2% of respondents were women and 48.8% were men, reflecting a similar distribution to Spain’s visitors. As all questions required a response before moving to the next, there were no missing values in this study.

Table 1.

Dependent and independent variables operationalization plus control variables.

The academic field of tourism has seen extensive research into the analysis and measurement of tourist destination choice. However, most literature has attempted to understand the factors influencing tourists’ choices by predominantly using qualitative methodologies (e.g., case studies) to identify these preferences. Consequently, the scales were developed based on prior works, when possible, in conjunction with international institutions’ reports or indexes when necessary.

Specifically, the scale used to assess the dependent variable (CHOICE) was derived from Um and Crompton’s (1992) study and further refined by the recent Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (2022). The factors considered by the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (NBI) are grouped into several categories (tourism, people, investment and immigration, export, politics, culture, and heritage), each designed to capture different dimensions of a country’s global image. Regarding the tourism dimension, the NBI measures the level of interest respondents have in visiting a country if money were no object. It also evaluates the perceived natural and cultural attractions of the country, assessing whether it is seen as an appealing place to visit.

Concerning the independent variables, it should be noted that items 2 and 4 of the state social responsibility (SSR) scale align with Font and Lynes [47]. The scale was further refined by incorporating measures of governance quality from the World Bank Governance Indicators (item 1) and the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) by the World Economic Forum, which includes pillars such as “Safety and Security” and “Poverty and Equality”.

Finally, the TTCI includes the “Environmental Sustainability” pillar, which encompasses all three items of the (SUSTAINABILITY) scale. The works of Mathis and Rose and Goffi, Cucculelli, and Masiero [48,49] highlight policies related to environmental conservation and the use of renewable energy in tourism, which were also considered by the authors in the elaboration of this scale.

- (B)

- Measurement of the Control Variables

To capture the factors driving the tourists’ destination choice, in conjunction with the independent variables proposed in this study (SSR and Sustainability), we controlled for some extra variables. Particularly, prior literature has suggested the growing impact of the host country’s life quality [15], and image [50,51,52]. For that reason, a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“I Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“I Strongly A5gree”) was elaborated to address their influence on the dependent variable.

As with the dependent and independent variables, no single scale was identified by the authors to assess the control variables, specifically the Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and IMAGE. To address this issue, Uysal et al. (2016) was considered in developing the QLS scale. This work reviews various aspects contributing to the quality of life in tourism destinations, including living conditions and educational opportunities, and aligns with the OECD Better Life Index, which provides data on multiple dimensions of quality of life, including education, living conditions, and health [53].

Regarding the country’s image (IMAGE), the authors considered Pappu, Quester, and Cooksey’s (2007) study, which emphasizes the association between country image and the perceptions of products and people from that country. These items were further refined by considering the Nation Brands Index (NBI) by Simon Anholt, which assesses the overall image and reputation of countries.

In conjunction with the above-mentioned control variables (QLS and IMAGE), literature has highlighted the significant role of trip distance in influencing tourists’ decision-making processes [54,55]. Consequently, the geographical distance (GEODIST) between tourists’ residences and their destinations was included as a control variable. In some cases, the exact physical locations of all respondents were not available. To address this issue, we followed the methodology used in prior international management studies [56,57], estimating this variable based on the air distance in kilometers between the capital of the host country (Madrid, by default) and the capital of the respondent’s home country. In our sample, this distance ranges from 1103 km (Paris) to 9214 km (Beijing).

Additionally, affordability has been identified in previous works as a factor influencing tourists’ destination choices [58]. Purchasing power parity (PPP) is an economic measure that compares price levels between countries to determine their relative purchasing power; therefore, it was included in this study as another control variable. To assess this variable, we referenced the latest report published by the World Bank in 2022. In our analysis, the variable ranges in absolute values from Mexico (USD 3,198,026 million) to the USA (USD 26,854,596 million). In terms of per capita values, the range extends from USD 13,803.7 (Mexico) to USD 80,035.5 (USA).

For clarity, Table 2 summarizes the operationalization of the dependent, independent, and control variables used in this study.

Table 2.

Summary of variables operationalization.

3.3. Data Analysis

To assess the reliability of the measurement scales, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was evaluated. As shown in Table 3 Cronbach’s alpha values for the full scale ranged from 0.758 to 0.902, indicating strong internal consistency. Furthermore, reliability was further confirmed by the lowest composite reliability value of 0.786, significantly exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 [65]. Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) coefficients consistently exceeded 0.50, meeting the criterion for demonstrating convergent validity.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity analysis.

Prior to performing an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis to test the research hypotheses, a principal component analysis was conducted to consolidate the items of the various variables into single values. The results are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Dimension reduction.

4. Results

An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis was performed to determine the impact of the proposed independent variables on tourists’ choice of destination (dependent variable).

The OLS method was chosen because the primary focus of this study is to explore the relationship between the variables at a specific point in time, rather than examining dynamic behavior or trends over time, which are more characteristic of time-series data. Furthermore, OLS is a widely accepted and appropriate method for cross-sectional data analysis, especially when the primary goal is to estimate the average effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The data used in this study do not exhibit characteristics typically associated with time-series data, such as autocorrelation or non-stationarity, which would necessitate the use of alternative estimators like generalized least squares (GLS) or autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models.

To ensure the robustness of the OLS results, diagnostic tests for multicollinearity were conducted. The collinearity statistics, including Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance, for all variables included in the empirical study are provided in Table 5. Specifically, VIF values less than five are preferred to ensure minimal multicollinearity. As Tolerance is the reciprocal of VIF, a value greater than 0.1 is considered acceptable. This corresponds to a VIF value less than 10. However, a Tolerance value greater than 0.2 is often used as a more conservative threshold, corresponding to a VIF value less than five [66]. In our analysis, none of these thresholds were exceeded, revealing that multicollinearity was not a concern in this study.

Table 5.

OLS regression analysis.

The OLS analysis demonstrates that the proposed model is significant at the 0.00 level, indicating that the independent variables effectively capture the factors influencing the selection of Spain as a tourist destination. The model for predicting “Country Choice” as a tourist destination shows strong performance, with an R2 of 0.794, meaning that 79.4% of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the independent variables. The Adjusted R2 of 0.630, which accounts for the number of predictors, also indicates a strong relationship, though more conservatively. The F-statistic of 1705.61, with a p-value of less than 0.001, confirms that the model is statistically significant, demonstrating that the predictors collectively offer a meaningful explanation of the variation in the dependent variable.

In particular, our results demonstrate a positive correlation between the country’s social initiatives (SSR) and sustainable practices (SUSTAINABILITY) with tourists’ choice of destination, thereby validating both H1 and H2 at the 0.01 significance level. Additionally, the results show a positive and statistically significant effect of both the country’s image (IMAGE) and the host country’s quality of life on the decision to choose a tourist destination, with a 99% confidence level. Furthermore, our analysis indicates that the home country’s purchasing power parity (PPP) positively impacts customer destination choice at the 0.01 significance level. Finally, the results confirm that the geographical distance (GEODIST) between the host and home country is an important driver of tourists’ destination choice, as it negatively affects this decision at the 99% confidence level.

5. Discussion

Tourism is one of the fastest-growing and most dynamic industries worldwide [21], playing a crucial role in the economic and social well-being of many regions and communities [7]. Notably, tourism has been identified as a key driver of economic recovery and growth, with data indicating a return to 95% of pre-pandemic tourist numbers by the end of 2023 [1]. In the case of Spain, empirical evidence supports the significance of tourism in driving economic growth, particularly during and after financial crises [67]. However, the negative environmental impacts of tourism are substantial.

In a context where social causes and sustainability are increasingly prioritized, tourism destinations that emphasize sustainability and social issues can differentiate themselves in a competitive market [8]. More specifically, social responsibility and sustainability are becoming increasingly critical factors in tourism destination choice [32], reflecting a growing awareness and preference among tourists for environmentally and socially responsible travel options [68]. In response to these challenges, tourism destinations have increasingly incorporated social and sustainable initiatives to address criticism and reaffirm their commitment to the social contract [2]. To shed light on this issue, this study examines the role that social issues and environmental responsibility may play in tourists’ destination choices through the lens of Stakeholder Theory, focusing on Spain, the second-largest tourism destination in the world.

Our findings underscore the importance of strengthening the state social responsibility (SSR) of destinations to enhance relationships with stakeholders and generate societal and organizational value [18], aligning with the tenets of Stakeholder Theory [25]. Spanish support for the LGBTQ community serves as an illustrative case. For LGBTQ travelers, choosing a welcoming and inclusive destination is vital when planning their vacations. Despite progress, discriminatory barriers still exist that affect how these travelers are received worldwide, and most consider their safety and well-being when choosing a destination. To facilitate this search, Booking awards the Travel Proud badge to inclusive accommodations. Currently, over 26,000 hotels across 118 countries and territories, in more than 7030 cities have received this recognition. Spain ranks third globally for LGBTQ-friendly accommodations, behind only Italy and the United States. Additionally, Spain hosts one of the world’s largest Pride celebrations, attracting 1.5 million people annually [69].

Spain’s dedication to supporting minorities extends beyond the LGBTQ community. The “Spain is Accessible” website is a prominent example, serving as the official tool used by Spanish institutions in collaboration with the Spanish Accessible Tourism Network since 2016. This initiative standardizes criteria to ensure accessibility for all places and activities, providing a comprehensive guide with guarantees for travelers with disabilities, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

“Spain is Accessible” official website. Source: http://www.spainisaccessible.com/index (accessed on 20 June 2024).

Our findings further indicate that the incorporation of sustainable initiatives by a destination, alongside social practices, is positively associated with tourists’ destination choices. As societal expectations for sustainable solutions increase, top destinations are more frequently urged to adopt environmental initiatives, demonstrating their environmental commitment [2]. This strategic approach not only aligns the destination with community values [7] but also helps protect the planet for future generations [11]. For instance, Booking.com’s 2024 Sustainable Travel Research Report found that 75% of global travelers want to travel more sustainably over the next 12 months, and 43% would feel guilty when making less sustainable travel choices [70].

In line with these objectives, many leading destinations are modifying their tourist offerings to become more resilient and sustainable. This often involves adapting a country’s tourism offerings to reduce seasonality. For example, Slovenia has committed to 20 projects aimed at transforming mountain destinations into year-round resorts for active holidays outside the ski season. Similarly, Norway’s “Norway All Year Round” plan aims to distribute tourist traffic across various locations and seasons.

What sets Spain apart from other destinations is its proactive commitment to implementing sustainable and mindful practices. Initially, Spain developed the Sustainable Tourism Strategy 2030, a national agenda designed to help the tourism sector address medium- and long-term challenges, including socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. An illustrative example of this commitment is the effort by Spain’s large hospitality providers to reduce carbon emissions: Melia opened Menorca’s first carbon-neutral luxury hotel in 2022, showcasing carbon-neutral operations, energy-efficient buildings, and circular models for water resources. Iberostar has also committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2030, target that is 20 years ahead of many other international hospitality brands [71]. Notably, Spain is among the best-performing countries in terms of low-carbon room footprint and meeting footprint [45]. Furthermore, Spain’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) index has reached 91.4 out of 100, which represents an excellent score. It is not surprising then, that in the “Best in Travel 2024” report, Spain was ranked the second-best sustainable destination worldwide, just behind Ecuador [72].

Moreover, this study underscores the paramount role of additional variables in tourists’ decision-making processes regarding destination choice. Notably, the host country’s quality of life and image are significant factors that positively affect the likelihood of choosing a destination for tourism, which aligns with prior literature [61,73]. Our findings confirm these variables as strong attractors and essential drivers in the tourism destination choice process, contributing to a country’s competitive edge in the global tourism market. Therefore, they have to be considered alongside SSR (social sustainability responsibility) and the country’s sustainability.

These findings are not restricted to Spain as a tourism destination, as successful countries such as Australia and Canada illustrate similar results. Particularly, Australia leverages its reputation for adventure and environmental stewardship to attract tourists interested in nature and outdoor activities. Canada’s diverse cultural experiences and high standard of living make it an attractive destination for a broad demographic of tourists. These countries ranked 8th and 9th, respectively, in global tourist receipts in 2023 [13]. These results have important implications for tourism policymakers and industry stakeholders globally. Countries that seek to remain competitive in the global tourism market must prioritize the integration of sustainability and social responsibility into their destination offerings. By doing so, destinations can not only meet the growing expectations of tourists who demand environmentally and socially responsible travel options but also foster long-term sustainability and resilience within the tourism sector. For policymakers, this means investing in infrastructure that supports sustainable tourism, such as carbon-neutral accommodations, and promoting inclusive practices that address the needs of diverse tourist segments. By aligning tourism policies with the principles of state social responsibility (SSR), governments can generate societal and organizational value while strengthening relationships with stakeholders. This approach not only enhances a destination’s reputation but also contributes to the wider objectives of sustainable development, such as those outlined in the united nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGS).

Industry stakeholders, including hotel operators and tour operators, must also recognize the importance of sustainability and social responsibility in attracting tourists. Investing in green certifications, promoting sustainable travel practices, and supporting local communities can differentiate destinations in a competitive marketplace.

Thus, our findings confirm that tourism policymakers should focus on enhancing these aspects to bolster their country’s attractiveness and competitive positioning in the tourism industry. In conclusion, the study underscores the need for a proactive and strategic approach to sustainability and social responsibility in tourism. As tourism destinations continue to face growing pressures to balance economic growth with environmental and social responsibility, the insights from this study provide a roadmap for countries seeking to navigate these challenges successfully.

Regarding the role of geographical distance, the present work confirms its relevance in the tourist destination choice process, as suggested by prior literature [74]. This is further illustrated by the fact that among the top 10 countries sending tourists to Spain, all except the USA are European. However, with the widespread use of airplanes as the primary means of transportation in the tourism sector, the distance between different countries has been reduced to a few hours by air. Consequently, this variable is becoming less significant, as confirmed by the low coefficient value obtained in the OLS regression conducted in this study. Despite this, the effect of geographical distance still holds considerable importance in the tourist destination choice process, and policymakers must take it into account as a factor influencing tourists’ decision-making processes.

Finally, the home country’s purchasing power parity (PPP) emerges as a factor influencing tourists’ destination choices. This finding aligns with prior literature highlighting the economic factors shaping travel [15]. Particularly, higher PPP levels indicate greater economic stability and disposable income among residents, enabling tourists to consider destinations offering superior experiences and amenities, such as those found in Spain.

6. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively explore the influence of social and sustainable practices on tourists’ destination choices in the context of international tourism, with a particular focus on Spain. By integrating Stakeholder Theory, we provide a novel theoretical framework that bridges the gap between corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and tourism decision-making. This contribution is significant as it underscores the growing importance of aligning tourism strategies with the diverse interests and expectations of stakeholders, thereby fostering more sustainable and successful outcomes within the sector.

The study’s novelty lies in its detailed examination of how social and sustainability initiatives shape tourist behavior, a subject of increasing relevance in today’s tourism landscape. Our findings not only add to the theoretical discourse by reinforcing the positive association between social responsibility, sustainability, and destination choice, but they also offer practical insights for industry practitioners. Specifically, the study highlights the potential for destinations to enhance their competitive edge by prioritizing these practices, appealing to the growing segment of tourists who favor environmentally and socially responsible travel options.

For managers and policymakers, our research also provides actionable guidance. By demonstrating how factors such as geographical distance, destination image, quality of life, and purchasing power parity influence tourism dynamics, we offer a roadmap for refining tourism strategies and managerial decisions. Moreover, the case of Spain serves as a valuable model for other destinations seeking to integrate social and environmental considerations into their strategic frameworks. This approach not only increases the likelihood of attracting tourists but also positions destinations as leaders in sustainability and social responsibility, yielding long-term benefits.

In conclusion, this study makes a significant contribution to both theory and practice by offering new perspectives on the role of social and sustainable practices in tourism. It provides a robust foundation for further research and a practical toolkit for industry professionals and policymakers striving to develop more sustainable and competitive tourism strategies.

7. Limitations and Further Research Avenues

We conclude this paper by identifying some limitations and offering suggestions for further research. The first limitation of this study is its focus on Spain. Most research in the tourism sector is confined to a single country, either the tourists’ country of origin or the destination country [11]. This study considers six countries of origin, collectively representing nearly 70% of the 85 million tourists that Spain received in 2023. While concentrating on Spain, the study offers potential for broader insights by proposing comparative studies involving other countries to enhance the understanding of the impact of sustainability and CSR on tourists’ destination choices. Additionally, investigating these relationships in other countries of origin could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Secondly, although this study primarily relied on online surveys, which may have underrepresented older individuals or those less familiar with the internet, future research could benefit from a more diverse data collection approach. Incorporating methods like focus groups, in-depth interviews in future studies could help address potential biases and capture a broader range of perspectives.

Finally, conducting surveys to understand tourists’ preferences and willingness to support sustainable tourism destinations can help quantify the influence of CSR and sustainability on tourist choices. We then propose, as a further research direction, a comparative analysis of tourist influx in destinations with high CSR and sustainability standards versus those without, to empirically strengthen our knowledge in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B.; Methodology, V.B.; Validation, V.B.; Formal analysis, V.B.; Investigation, V.B. and J.C.; Resources, J.C.; Data curation, V.B. and J.C.; Writing—original draft, V.B.; Writing—review & editing, V.B. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable because the data will be used for further academic work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eurostat. Tourism Industries–Employment. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tourism_industries_-_employment (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Travel International. Carbon Footprint of Tourism. 2024. Available online: https://sustainabletravel.org/issues/carbon-footprint-tourism/ (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- The World Counts. Tourism Often Leads to Overuse of Water. 2024. Available online: https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/transport-and-tourism/negative-environmental-impacts-of-tourism (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- UN Tourism Report. International Tourism to Reach Pre-Pandemic Levels in 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-to-reach-pre-pandemic-levels-in-2024#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20first%20UNWTO,estimated%201.3%20billion%20international%20arrivals (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- La Moncloa. La llegada de Turistas Internacionales en 2023 Supera las Previsiones y Alcanza por Primera vez los 85 Millones. 2024. Available online: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/industria-turismo/Paginas/2024/020224-record-turistas-internacionales.aspx (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Santos, V.; Sousa, M.J.; Costa, C.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Tourism towards sustainability and innovation: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Vila, N.; Carles, A.O.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Sustainability in tourism after COVID-19: A systematic review. In Sustainability and Competitiveness in the Hospitality Industry; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 166–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, K.; Seabra, C.; Kabia, S.K.; Ashutosh, K.; Gangotia, A. COVID crisis and tourism sustainability: An insightful bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilufya, A.; Hughes, E.; Scheyvens, R. Tourists and community development: Corporate social responsibility or tourist social responsibility? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Tamuliene, V. Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Green Consumption in Tourism. Sustainability 2023, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Christofi, M.; Giacosa, E.; Serravalle, F. Sustainable development in tourism: A stakeholder analysis of the Langhe Region. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 846–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- ICEX. Spain, a World Leader in Tourism. 2024. Available online: https://www.investinspain.org/content/icex-invest/en/sectors/tourism.html (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Moreno-Luna, L.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez, M.S.O.; Castro-Serrano, J. Tourism and sustainability in times of COVID-19: The case of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hörisch, J.; Freeman, R.E. Business cases for sustainability: A stakeholder theory perspective. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, T.S.; Johannsdottir, L. Influencing sustainability within the fashion industry: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garvare, R.; Johansson, P. Management for sustainability—A stakeholder theory. Total Qual. Manag. 2010, 21, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J.M.; Bonilla-Priego, M.J.; Ortas, E. Corporate social responsibility and organisational performance in the tourism sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, V. The shift from fast fashion to socially and sustainable fast fashion: The pivotal role of ethical consideration of consumer intentions to purchase Zara. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 4315–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Nitivattananon, V.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Pandey, R. An Application of the Stakeholder Theory and Proactive-Reactive Disaster Management Principles to Study Climate Trends, Disaster Impacts, and Strategies for the Resilient Tourism Industry in Pokhara, Nepal. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in traditional villages: The lens of stakeholder theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattera, M.; Baena, V. Corporate reputation and its social responsibility: A comprehensive vision. Cuad. Estud. Empres. 2012, 22, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez-Ponce, E.; Clarke, A.; MacDonald, A. Business contributions to the sustainable development goals through community sustainability partnerships. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1239–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Corporate social responsibility: From founders to millennials. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Weber, J., Wasieleski, D.M., International Association for Business and Society, Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2018; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brydges, T.; Henninger, C.E.; Hanlon, M. Selling sustainability: Investigating how Swedish fashion brands communicate sustainability to consumers. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Jallu, K.; Kumar, A. A Study of connection between Culinary Tourism and Destination Marketing. Int. J. Multidimens. Res. Perspect. 2023, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, C.; Rodrigues, P.; Gomez-Suarez, M. A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of Sustainability and Smart Tourism. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; King, B.; McKercher, B. Reflecting on tourism and COVID-19 research. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Stasiak, J. Domestic Tourism Preferences of Polish Tourist Services’ Market in Light of Contemporary Socio-economic Challenges. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism, ICSIMAT 2023, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Kavoura, A., Borges-Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriadi, B.W.; Hurriyati, R.; Widjajanta, B. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Behavior in Tourism Sector. In Proceedings of the 6th Global Conference on Business, Management, and Entrepreneurship (GCBME 2021), Bandung, Indonesia, 18 August 2021; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 312–316. [Google Scholar]

- Marques Santos, A.; Madrid, C.; Haegeman, K.; Rainoldi, A. Behavioural changes in tourism in times of COVID-19. JRC121262 2020, 22, 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J. Case Studies of Social Responsibility in Tourism. In Social Responsibility in Tourism: Applications, Best-Practices, and Case Studies; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.M.; Felps, W.; Bigley, G.A. Ethical theory and stakeholder-related decisions: The role of stakeholder culture. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, B.A. Correlational Research of Antecedents in Tourism Destination Choice. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; Volume 922. [Google Scholar]

- L’Abate, V.; Vitolla, F.; Esposito, P.; Raimo, N. The drivers of sustainability disclosure practices in the airport industry: A legitimacy theory perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderman, S.; Dolles, H. Handbook of Research on Sport and Business; Edward Elgar Publisher: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baena, V. Global marketing strategy in professional sports. Lessons from FC Bayern Munich. Soccer Soc. 2019, 20, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GreenView. GreenView Hotel Footprinting Tool. 2024. Available online: https://greenview.sg/services/greenview-hotel-footprinting-tool/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Kwon, K.; Lee, J. Corporate social responsibility advertising in social media: A content analysis of the fashion industry’s CSR advertising on Instagram. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 26, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Lynes, J. Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, E.; Rose, J. The influence of corporate social responsibility on tourism destination choices: A survey experiment. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapar, H.; Aslan, Ö. Factors affecting destination choice in medical tourism. Int. J. Travel Med. Glob. Health (IJTMGH) 2020, 8, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidebo, H.B. Factors determining international tourist flow to tourism destinations: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantakopoulou, I. Does health quality affect tourism? Evidence from system GMM estimates. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Lew, A.A. Tourist flows and the spatial distribution of tourists. In A Companion to Tourism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, K.S.; Batra, D.K. Tourist decision making: Exploring the destination choice criteria. Asian J. Manag. Res. 2016, 7, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Baena, V.; Cerviño, J. Identifying the factors driving market selection in Latin America: An insight from the Spanish franchise industry. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baena, V. The effect of franchisor characteristics and host country features on the foreign entry mode. Lessons from the Spanish franchise system lessons from the Spanish franchise system. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2018, 20, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Joshi, S. Trends in destination choice in tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric review. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2021, 10, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Crompton, J.L. The roles of perceived inhibitors and facilitators in pleasure travel destination decisions. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt-Ipsos. Nation Brands Index 2022. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2022-11/NBI%202022%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- World Economic Forum. Travel & Tourism Development Index 2023: Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Better Life Index 2022. Available online: http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G.; Cooksey, R.W. Country image and consumer-based brand equity: Relationships and implications for international marketing. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, C. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Ramón-Rodríguez, A.B.; Rubia, A.; Moreno-Izquierdo, L. Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid after the global economic and financial crisis? The case of Spain 1957–2014. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsunopparat, S.; Hu, X. Study of Influential Factors That Affect LGBTQ’s Travel Destination Choice Decision. Bus. Econ. Res. 2023, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International LGBTQ + Travel Association IGTLA Report–Spain. 2024. Available online: https://www.iglta.org/destinations/europe/spain/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Sustainable Travel Research Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/booking-sustainable-travel-report-2024/?lang=es (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- McKinsey & Company. Next Stop for Spanish Tourism Excellence: Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/next-stop-for-spanish-tourism-excellence-sustainability (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Looney Travel Best in Travel 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/best-in-travel (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Martín-Martín, O.; Cerviño, J. Towards an integrative framework of brand country of origin recognition determinants: A cross-classified hierarchical model. Int. Mark. Rev. 2011, 28, 530–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Y. The effect of distance on tourist behavior: A study based on social media data. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 82, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).