Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Financial Situation of Rural and Urban Households in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Financial Situation of Households—Literature Review

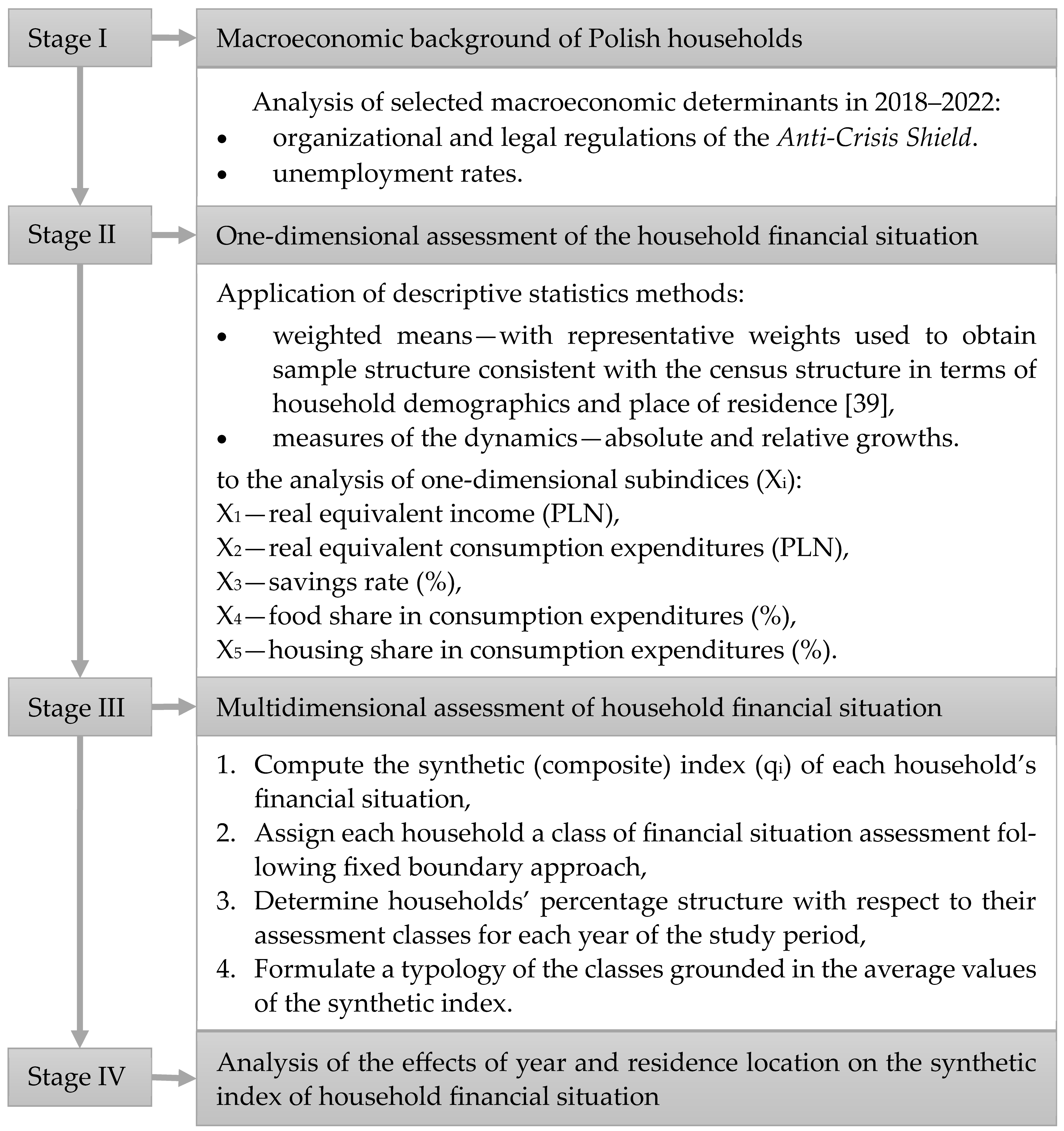

3. Materials and Methods

- normalizing partial indices (Xj) with min-max method:

- 2.

- 3.

- calculating Euclidean distance from the ideal () and anti-ideal ():

- 4.

- computing the synthetic index :

4. Results

4.1. Macroeconomic Determinants of the Financial Situation of Polish Households During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- environmental conditions (geographic and climatic)—the presence of fertile soil, mineral deposits, or environmental hazards (natural and anthropogenic);

- demographic, social and cultural background—the age structure, migrations, social norms, traditions and values; this category includes place of residence—urban or rural studied in this paper;

- economic fundamentals—country’s economic situation, unemployment, wage levels, inflation;

- political, legal and administrative framework—fiscal and redistributive policy, degree of economic freedom.

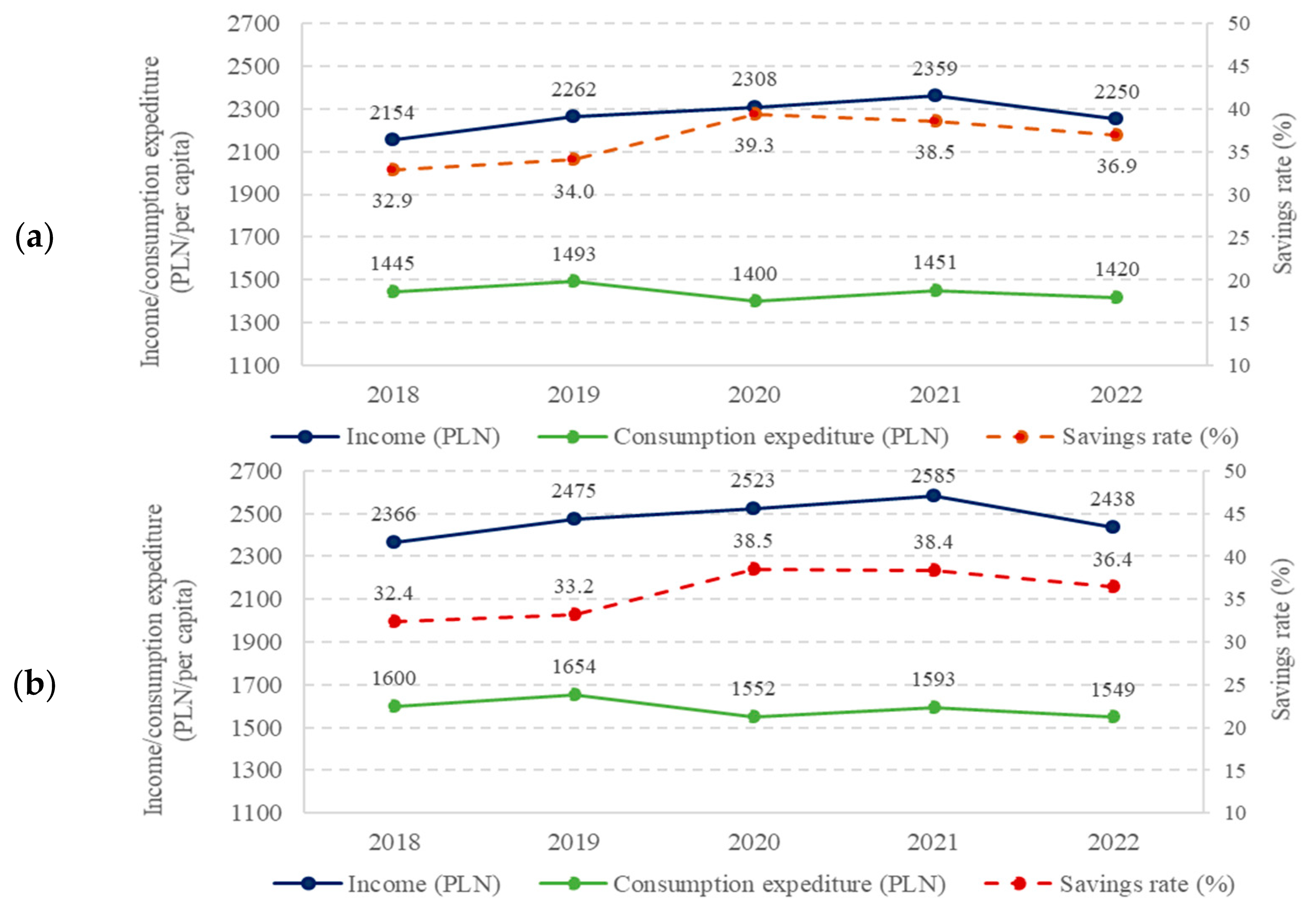

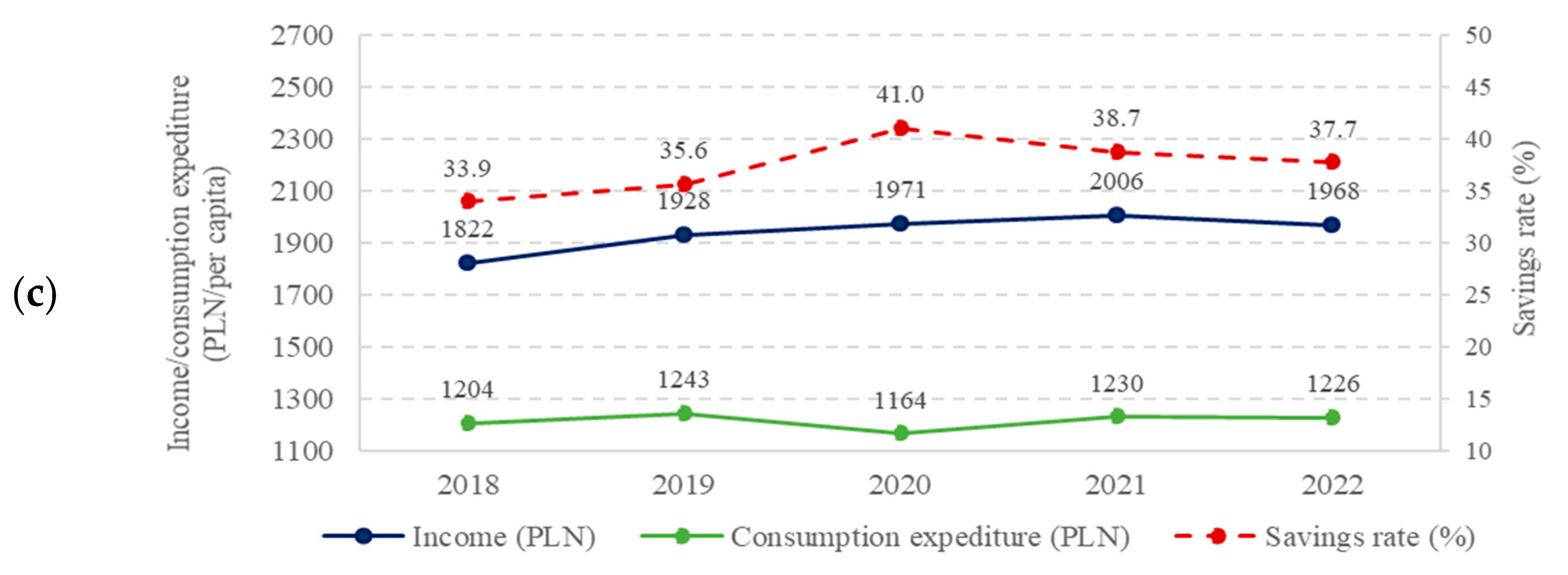

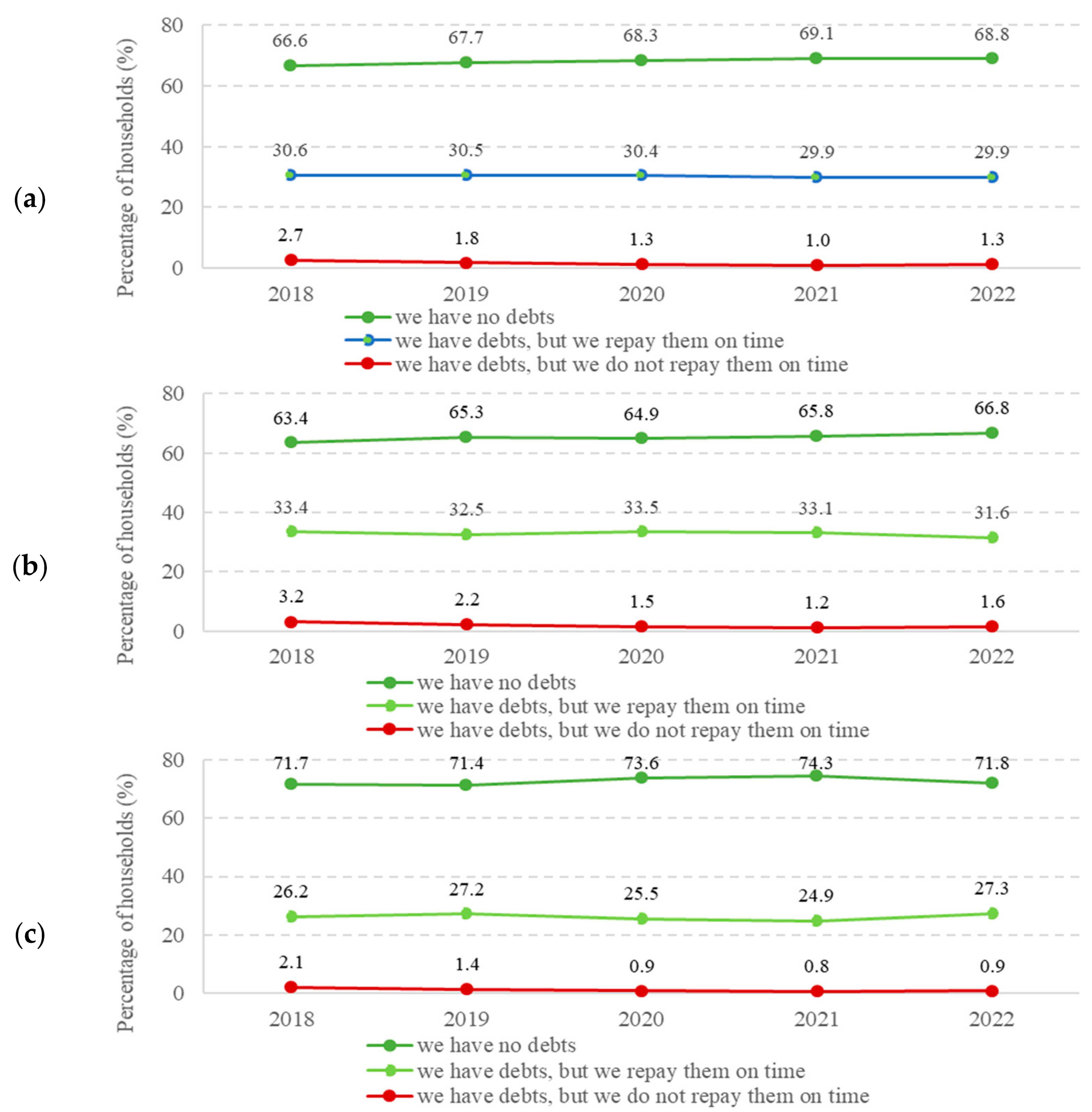

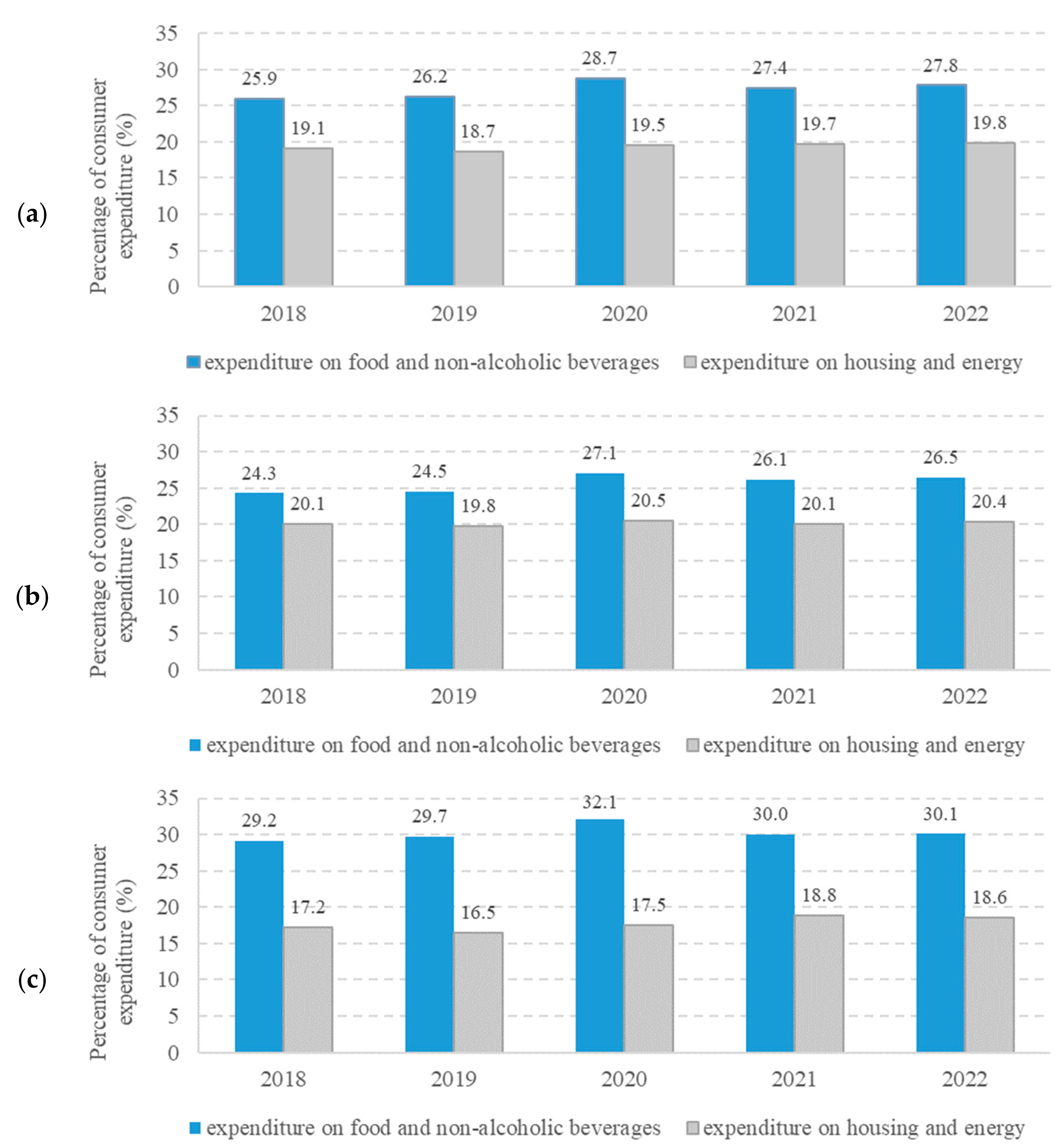

4.2. Unidimensional Assessment of Household Financial Situation

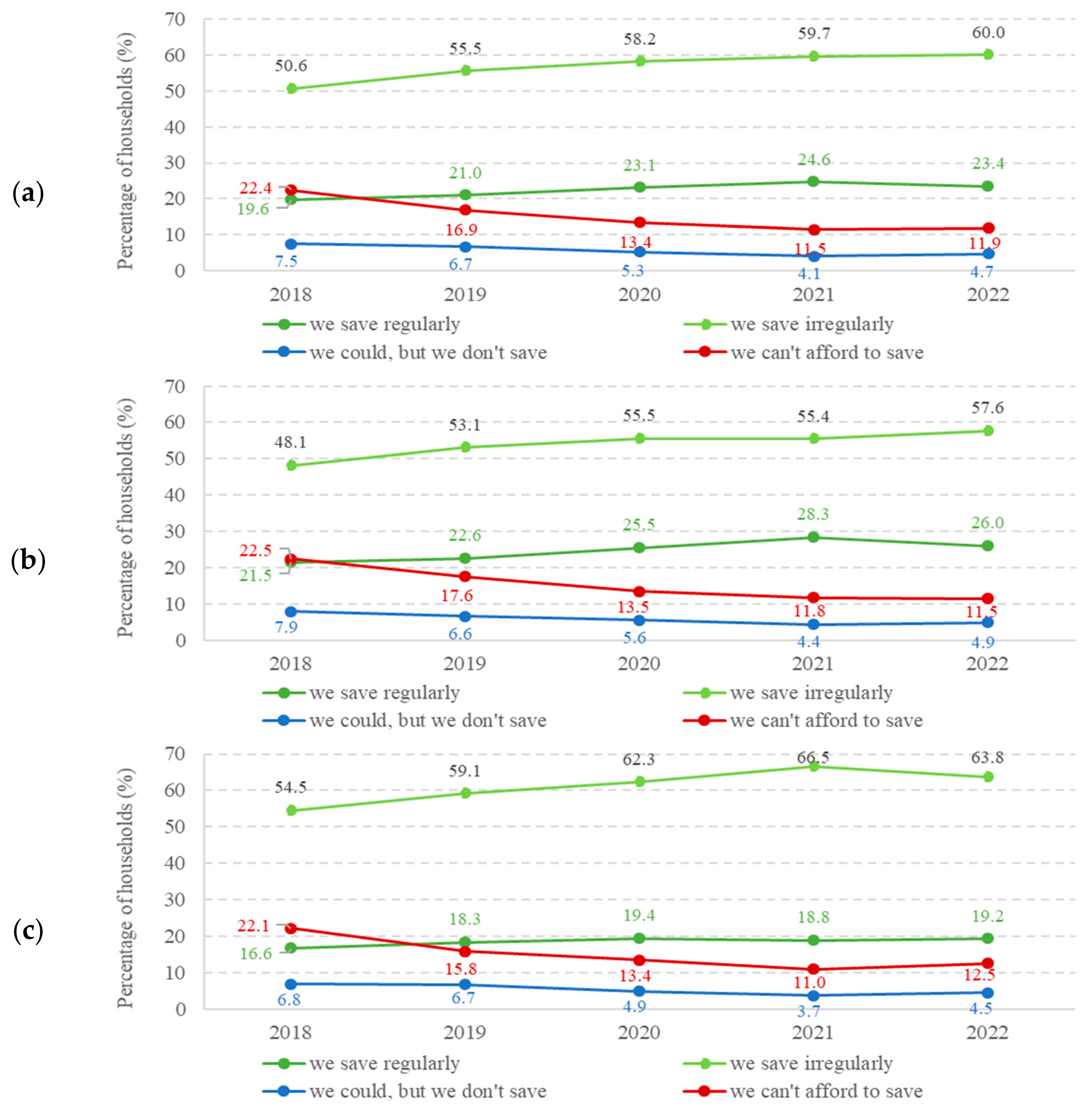

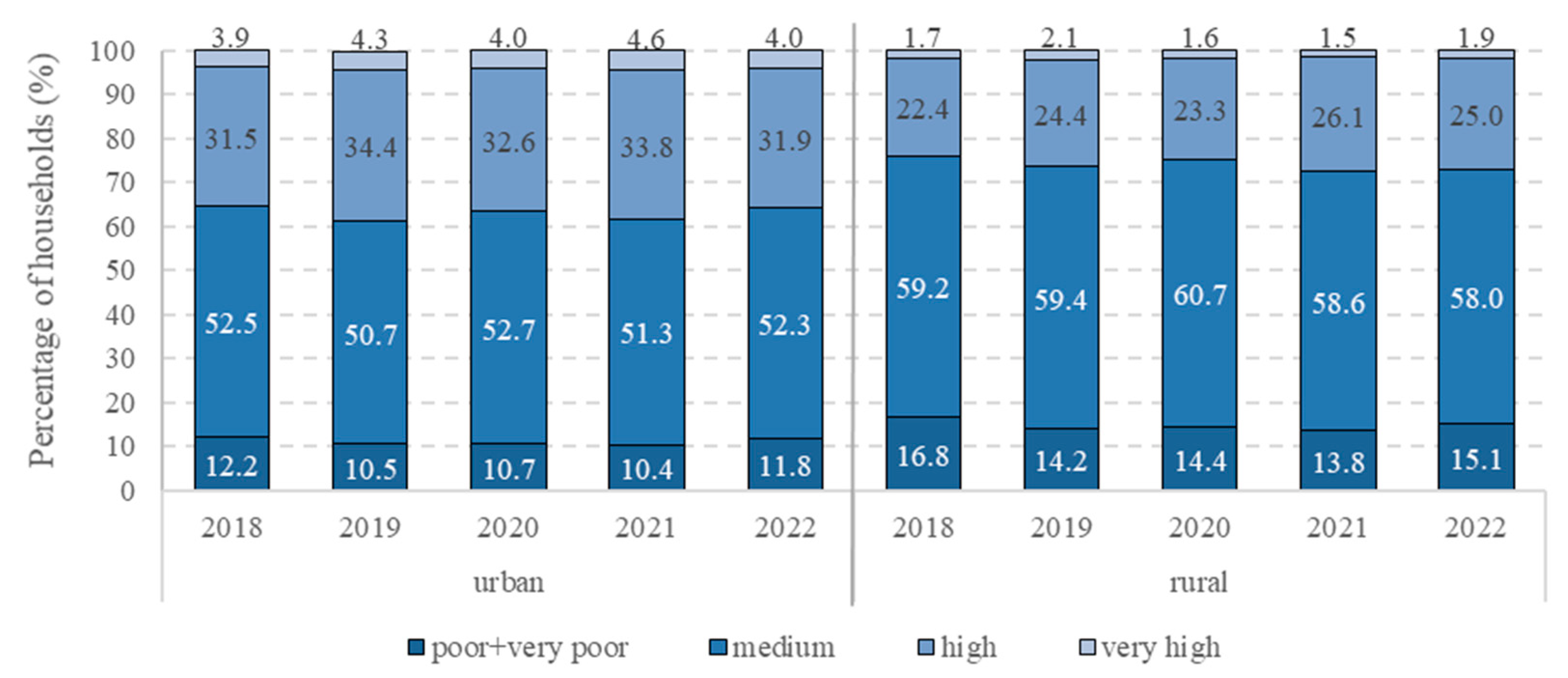

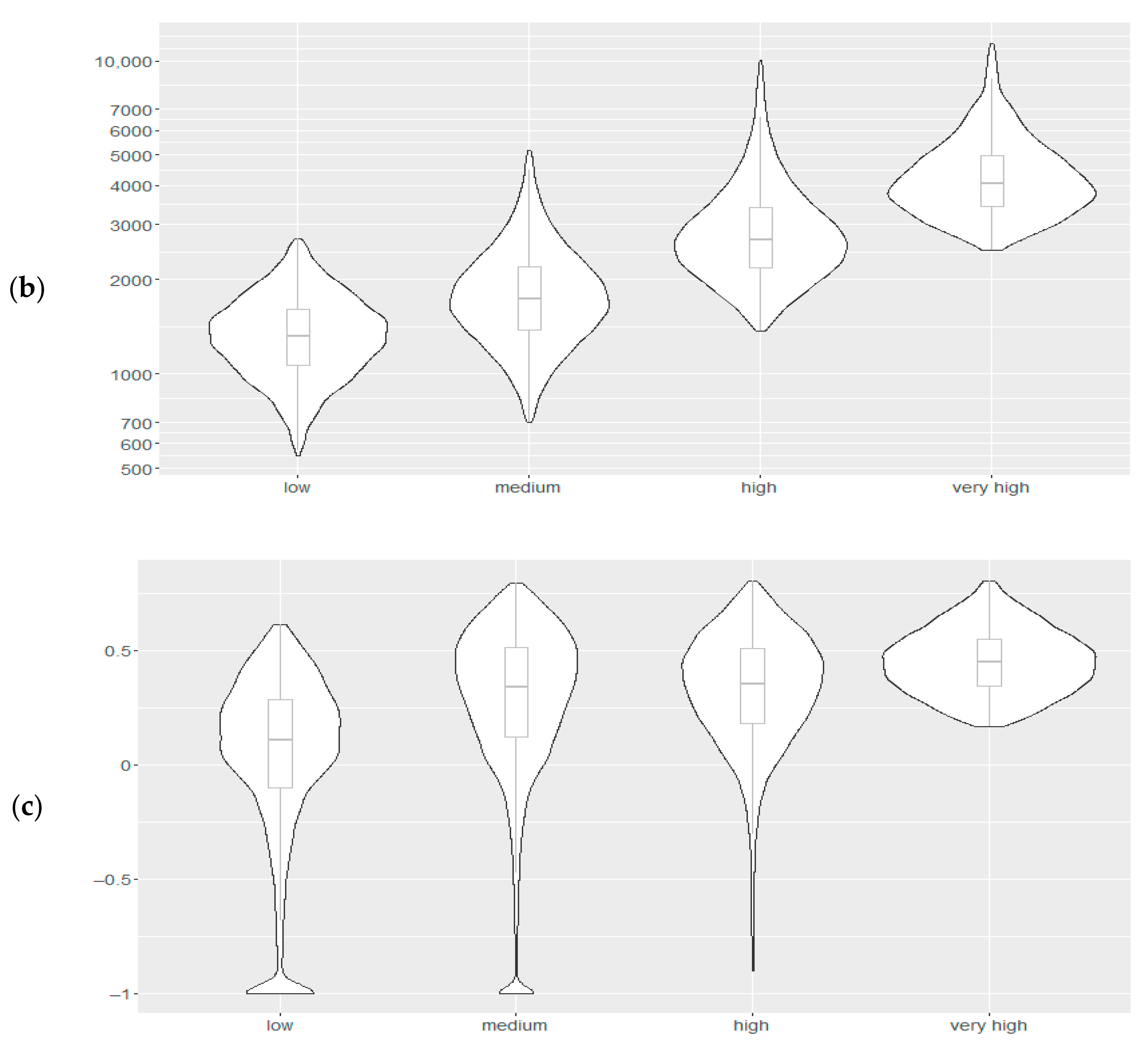

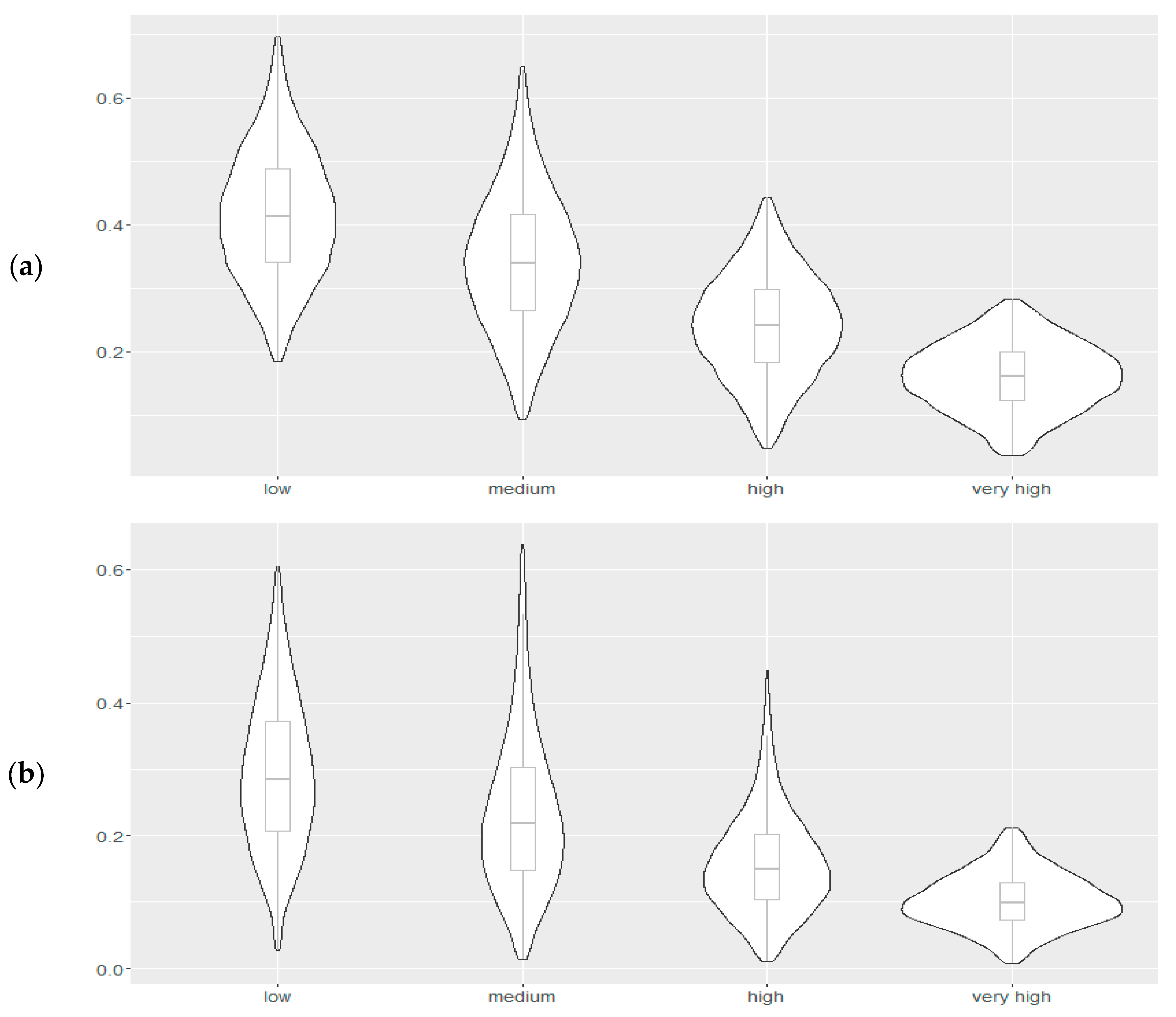

4.3. Multidimensional Assessment of Household Financial Situation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 20 marca 2020 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia na obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej stanu epidemii. Dz.U. z 2020; r. poz. 491 (Regulation of the Health Minister on the declaration of a state of epidemic in the territory of the Republic of Poland. J. Laws 2020; item 491). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000491/O/D20200491.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 12 maja 2022 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia na obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej stanu zagrożenia epidemicznego. Dz.U. z 2022; r. poz. 1028 (Regulation of the Health Minister on the declaration of a state of epidemic emergency in the territory of the Republic of Poland. J. Laws 2022; item 1028). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20220001028/O/D20221028.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 14 czerwca 2023 r. w sprawie odwołania na obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej stanu zagrożenia epidemicznego. Dz.U. z 2023; r. poz. 1118 (Regulation of the Health Minister on the revocation of a state of epidemic emergency in the territory of the Republic of Poland. J. Laws 2023; item 1118). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20230001118/O/D20231118.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- ESPON. Geography of COVID-19 Outbreak and First Policy Responses in European Regions and Cities. Final Report; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hołoga, D.; Winiarski, J. Ocena ekonomiczno-społeczna skutków walki z pandemią COVID-19 w Szwecji—Zasoby, działania, rezultaty. Współczesna Gospod. 2021, 12, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdin, S.; Jeanne, L.; Nadou, F.; Noiret, G. Does lockdown work? A spatial analysis of the spread and concentration of COVID-19 in Italy. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A.; Marcus, J. Using difference-in-differences to identify causal effects of COVID-19 policies. Surv. Res. Methods 2020, 14, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, B.; Dietrich, A.M.; Müller, G.J. The lockdown effect: A counterfactual for Sweden. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESPON. Territorial Impacts of COVID-19 and Policy Responses in European Regions and Cities. Final Report; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdin, S.; Cottereau, V.; Hermet, F.; Jean-Pierre, P.; Medeiros, E. How have Europe’s outermost regions dealt with the economic and social consequences of the COVID-19 crisis? Effects, policies and recommendations. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 1820–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, N.; Fessler, P.; Kalleitner, F.; Lindner, P. How has COVID-19 affected the financial situation of households in Austria? Monetary Policy & the Economy, Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank). 2021, issue Q4/20–Q1/21, 111–130. Available online: https://www.oenb.at/dam/jcr:d05a7f28-e7aa-43b8-b54d-9ffbe5ff3861/07_mop_Q4_20-Q1_21_How-has-COVID-19-affected-the-financial-situation.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Tokarz-Kocik, A.; Bera, A.; Drela, K.; Malkowska, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Labour Market in the Hotel Industry: Selected Conditions in Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadka, J.; Jęczmyk, A.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Niedbała, G.; Uglis, J.; Pietrzak-Zawadka, J. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Agritourism Farm Stays and Their Safety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolis, O.; Maidana, J.P.; Contreras, F.; Leal, D. Analyzing the Impact of COVID-19 on Economic Sustainability: A Clustering Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Mizen, P.; Smietanka, P.; Thwaites, G. The Impact of COVID-19 on Productivity. LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 121314, London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library. 2023. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w28233.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Pak, A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adekunle, A.I.; Rahman, K.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Eisen, D.P. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Jimenez, M.; Hormeño-Holgado, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.B.; Benitez-Agudelo, J.C.; Perez-Palencia, N.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in Public Mental Health: An Extensive Narrative Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniowska, A.M.; Rutecka-Góra, J.; Swacha-Lech, M.; Waliszewski, K. Wpływ Pandemii COVID 19 na Finanse Osobiste; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Szustak, G.; Gradoń, W.; Szewczyk, Ł. Household financial situation during the COVID-19 pandemic with particular emphasis on savings—An evidence from Poland compared to other CEE states. Risks 2021, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M. COVID-19 Pandemic as a Change Factor in the Labour Market in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9197. [Google Scholar]

- Wołoszyn, A. Nierówności dochodowe gospodarstw domowych w Polsce i ich uwarunkowania społeczno-ekonomiczne (Income Inequalities of Households in Poland and Their Socio-Economic Conditions); PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wołoszyn, A.; Wysocki, F. Income inequality of Polish rural and urban households in 2010–2017. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2020, 22, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.; Vigne, S. The causes and consequences of household financial strain: A systematic review. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2019, 62, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, M. Ocena społecznego zrównoważenia rozwoju w Polsce według kryterium dynamiki dochodów gospodarstw domowych. Nierówności Społeczne Wzrost Gospod. 2014, 37, 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rólczyński, T. The financial situation of Polish households—An assessment. Cent. East. Eur. J. Manag. Econ. 2013, 1, 177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher-Koenen, T.; Fessler, P.; Silgoner, M.A. Households’ Financial Resilience, Risk Perceptions, and Financial Literacy: Evidence from a Survey Experiment; ZEW Discussion Papers, No. 23–074; ZEW—Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Mannheim, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/283612 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Sokół, M.; Paździor, A.; Zienkiewicz, K. Postrzeganie sytuacji finansowej gospodarstw domowych w Polsce w warunkach niepewności (Perception of the financial situation of households in Poland in conditions of uncertainty). J. Mod. Sci. 2023, 5, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paździor, A.; Majek, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Household’s Financial Situation in Poland. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świecka, B.; Musiał, M. Diagnoza finansów gospodarstw domowych w największych miastach Polski. Finans. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2016, 82, 821–832. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.A. Farm Household Well-Being Comparing Consumption and Income-Based Measures; Economic Research Report, No 9; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kozera, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Wysocki, F. Sytuacja finansowa gospodarstw domowych zamieszkujących obszary wiejskie w Polsce po wstąpieniu Polski do Unii Europejskiej. Rocz. Nauk. Ekon. Rol. I Rozw. Obsz. Wiej. 2014, 101, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wereda, W.; Prokopowicz, D. Economic and financial situation of households in Poland—Analysis and diagnosis. Polityki Europejskie Finans. Mark. 2017, 18, 24–258. [Google Scholar]

- Fasianos, A.; Lydon, R. Do households with debt cut back their consumption more? New evidence from the United Kingdom. Bull. Econ. Res. 2022, 74, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagenhauf, D.; Garriga, C. Identifying “Default Thresholds” in Consumer Liabilities Using High Frequency Data; Meeting Papers; Society for Economic Dynamics: 2017; No. 1305. Available online: https://red-files-public.s3.amazonaws.com/meetpapers/2017/paper_1305.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Mazurek-Krasodomska, E. Sytuacja finansowa gospodarstw domowych i jej determinanty. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2011, 174, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Zalega, T. Assessment of the financial situation, determinants and the level of debt of seniors’ households. Nierówności Społeczne Wzrost Gospod. 2018, 55, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasa, A. Sytuacja finansowa Sektora Gospodarstw Domowych w I kw. 2017 r; Departament Analiz Ekonomicznych NBP: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wołoszyn, A.; Kozera, A.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Stanisławska, J. Nierówności dochodowe w różnych typach funkcjonalnych gmin wiejskich województwa wielkopolskiego (Income inequalities across functional types of rural communes of the Wielkopolska province). Zesz. Nauk. PTE Zielona Góra 2016, 5, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- CSO (Statistics Poland—CSO). Zeszyt metodologiczny. Badanie budżetów gospodarstw domowych (Methodological Notebook. Household Budget Survey); GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrans, P.; Speelman, C.; Campitelli, G. The Relationship Between Personal Financial Wellness and Financial, Wellbeing: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. J. Fam. Econ. 2014, 35, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSO (Statistics Poland—CSO). Household Budget Survey. Unpublished database, unidentifiable microdata for 2018–2022.

- Wołoszyn, A.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R. Dochód i wykształcenie jako determinanty stopy oszczędności gospodarstw domowych w Polsce. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego 2015, 74, 733–743. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, H. Skale Ekwiwalentności—Estymacja na Podstawie Kompletnych Modeli Popytu; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. Assessing the level of the material deprivation of European Union countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M.; Wachowicz, T. Wykorzystanie metody TOPSIS do oceny zróżnicowania rozwoju województw Polski w latach 2010–2014 w kontekście kształtowania się ładu instytucjonalnego. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2017, 469, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Wołoszyn, A.; Wysocki, F. Quality of life in farmers’ households assessment with TOPSIS method. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Scientific Conference “Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy”, Warsaw, Poland, 7–8 June 2018; Warsaw University of Life Sciences Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, Z. On the Problem of Weighting in International Comparisons. In Study VII of the UNESCO Statistical Office, Towards a System of Quantitative Indicators of Components of Human Resources Indicators Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision-Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, F. Metody Taksonomiczne w Rozpoznawaniu Typów Ekonomicznych Rolnictwa i Obszarów Wiejskich (Taxonomic Methods in Recognizing Economic Types of Agriculture and Rural Areas); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Wysocki, F. Right-Skewed distribution of features and the identification problem of the financial autonomy of local administrative units. In Classification and Data Analysis. SKAD 2019. Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organization; Jajuga, K., Batóg, J., Walesiak, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, S.; Polcyn, J.; Borychowski, M. Determinanty zrównoważonego rozwoju ekonomiczno-społecznego rodzinnych gospodarstw rolnych w Polsce. Ekonomista 2021, 1, 56–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, J.W. Korelacja i regresja w decyzjach kadrowych. Stud. Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katowicach 2015, 242, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bywalec, C. Ekonomika i Finanse Gospodarstw Domowych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Total Unemployment Rate. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00203/default/table (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- CSO (Central Statistical Office—CSO). Aktywność ekonomiczna ludności Polski—4 kwartał 2022 r. (Labour force Survey in Poland—Quarter 4/2022); GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z dnia 31 marca 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o szczególnych rozwiązaniach związanych z zapobieganiem, przeciwdziałaniem i zwalczaniem COVID-19, innych chorób zakaźnych oraz wywołanych nimi sytuacji kryzysowych oraz niektórych innych ustaw. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 568 (Act of 31 March 2020 amending the Act on special solutions related to the prevention, counteraction and combating of COVID-19, other infectious diseases and crisis situations caused by them and certain other acts. J. Laws 2020; item 568). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000568/O/D20200568.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Dębkowska, K.; Kłosiewicz-Gorecka, U.; Szymańska, A.; Ważniewski, P.; Zybertowicz, K. Tarcza Antykryzysowa… Koło ratunkowe dla firm i gospodarki? Gniazdowski, M., Kubisiak, A., Kutwa, K., Rybacki, J. (współpr.); Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z dnia 16 kwietnia 2020 r. o szczególnych instrumentach wsparcia w związku z rozprzestrzenianiem się wirusa SARS-CoV-2. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 695 (Act of 16 April 2020 on special support instruments in connection with the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. J. Laws 2020; item 695). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000695/O/D20200695.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Ustawa z dnia 14 maja 2020 r. o zmianie niektórych ustaw w zakresie działań osłonowych w związku z rozprzestrzenianiem się wirusa SARS-CoV-2. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 875 (Act of 14 May 2020 amending certain acts on protective measures in connection with the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. J. Laws 2020; item 875). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000875/O/D20200875.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Ustawa z dnia 19 czerwca 2020 r. o dopłatach do oprocentowania kredytów bankowych udzielonych przedsiębiorcom dotkniętym skutkami COVID-19 oraz o uproszczonym postępowaniu o zatwierdzenie układu w związku z wystąpieniem COVID-19. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 1086 (Act of 19 June 2020 on subsidies to interest on bank loans granted to entrepreneurs affected by the effects of COVID-19 and on simplified proceedings for approval of an arrangement in connection with the occurrence of COVID-19. J. Laws 2020; item 1086). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200001086/O/D20201086.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Ustawa z dnia 17 września 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o szczególnych rozwiązaniach związanych z zapobieganiem, przeciwdziałaniem i zwalczaniem COVID-19, innych chorób zakaźnych oraz wywołanych nimi sytuacji kryzysowych oraz niektórych innych ustaw. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 1639 (Act of 17 September 2020 amending the Act on special solutions related to the prevention, counteracting and combating of COVID-19, other infectious diseases and crisis situations caused by them and certain other acts. J. Laws 2020; item 1639). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200001639/O/D20201639.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Ustawa z dnia 9 grudnia 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o szczególnych rozwiązaniach związanych z zapobieganiem, przeciwdziałaniem i zwalczaniem COVID-19, innych chorób zakaźnych oraz wywołanych nimi sytuacji kryzysowych oraz niektórych innych ustaw. Dz.U. 2020; poz. 2255 (Act of 9 December 2020 amending the Act on special solutions related to the prevention, counteraction and combating of COVID-19, other infectious diseases and crisis situations caused by them and certain other acts. J. Laws 2020; item 2255). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200002255/O/D20202255.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Kańduła, S.; Przybylska, J. Financial instruments used by Polish municipalities in response to the first wave of COVID-19. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, J. Response of the Lithuanian municipalities to the First Wave of COVID-19. Balt. Reg. 2021, 13, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słomba, A.; Palac, P. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 oraz wojny rosyjsko-ukraińskiej na wskaźnik kondycji gospodarstw domowych w Polsce (The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war Russian-Ukrainian war on the condition index of the households in Poland). Probl. Econ. Law 2023, 8, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszała, M.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Wołoszyn, A.; Stanisławska, J. Consumer expenditure of rural households in Poland. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2023, 25, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Robert, F.A.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M. Constantine Yannelis, How Does Household Spending Respond to an Epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 834–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun-de Neef, Ö.H.; Schandlbauer, A. COVID-19, bank deposits, and lending. J. Empir. Financ. 2022, 68, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zheng, Y. COVID-19 vaccination and household savings: An economic recovery channel. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.; Łuczak, A.; Koziolek, A. The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, H.; Landmesser-Rusek, J. What explains the differences in material deprivation between rural and urban areas in Poland before and during the COVID-19 pandemic? Stat. Transit. New Ser. 2023, 24, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coibion, O.; Gorodnichenko, Y.; Weber, M. The Cost of the COVID-19 Crisis: Lockdowns, Macroeconomic Expectations, and Consumer Spending; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Working Paper No. 27141; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27141/w27141.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Baker, S.R.; Farrokhnia, R.A.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M.; Yannelis, C. How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 834–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatt, C.S. A Tale of Two Crises: The 2008 Mortgage Meltdown and the 2020 COVID-19 Crisis. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 759–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołoszyn, A.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R. Income inequality of rural households and the sources of their income. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2024, 26, 324–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kozera, A.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Stanisławska, J. Niedobory konsumpcji w gospodarstwach domowych rolników po wstąpieniu Polski do UE. Rocz. Nauk. SERiA 2014, 16, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, S. Ubóstwo i wykluczenie na wsi. In Polska Wieś 2022. Raport o Stanie Wsi; Wilkin, J., Hałasiewicz, A., Eds.; Wyd. FDPA, WN Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Twardzik, M. Rural areas in Poland—Changes since joining the European Union. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring rozwoju obszarów wiejskich. Etap IV. Dekada przemian społeczno-gospodarczych (Monitoring of Rural Development. Stage IV. A Decade of Socio-Economic Changes); Fundacja Europejski Fundusz Rozwoju Wsi Polskiej, Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywińska-Rąpca, M.; Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M. Financial Situation In The Assessments of the Head of the Household and their Relationship with Debt in Different Phases of the Life Cycle: A Case Study (Poland). J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2023, 2023, 426741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Assessment of Household Financial Situation | Range of Synthetic Index (qi) |

|---|---|---|

| I | very high | ⟨0.8; 1.0⟩ |

| II | high | ⟨0.6; 0.8) |

| III | medium | ⟨0.4; 0.6) |

| IV | low | ⟨0.2; 0.4) |

| V | very low | ⟨0.0; 0.2) |

| Year | Quarter | Unemployment Rate in Quarters | Unemployment Rate in Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Poland | Urban | Rural | Poland | ||

| 2018 | I | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| II | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | ||||

| III | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.8 | ||||

| IV | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3.8 | ||||

| 2019 | I | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| II | 3.0 | 3.5 | 3.2 | ||||

| III | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | ||||

| IV | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.9 | ||||

| 2020 | I | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| II | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | ||||

| III | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.3 | ||||

| IV | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | ||||

| 2021 | I | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| II | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | ||||

| III | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | ||||

| IV | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.9 | ||||

| 2022 | I | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| II | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.6 | ||||

| III | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.9 | ||||

| IV | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.9 | ||||

| For Employees | For Employers |

|---|---|

|

|

| Term | Estimate | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.5789 | 0.0009 | 643.2698 | 0.000 |

| Y2020 | −0.0084 | 0.0013 | −6.5805 | 4.71×10−11 |

| Y2021 | 0.0014 | 0.0013 | 1.0589 | 0.290 |

| Y2022 | −0.0062 | 0.0013 | −4.8529 | 1.22×10−06 |

| CLrural | −0.0370 | 0.0014 | −25.7186 | 1.73×10−145 |

| Y2020:CLrural | 0.0002 | 0.0020 | 0.0888 | 0.929 |

| Y2021:CLrural | −0.0050 | 0.0020 | −2.4638 | 0.014 |

| Y2022:CLrural | 0.0037 | 0.0020 | 1.8349 | 0.067 |

| R-squared | 0.0216 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.0215 | |||

| Sigma | 8.6081 | |||

| AIC | −127,029.05 | |||

| Descriptive statistic (mean ± standard deviation) | ||||

| Location class | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| rural | 0.542 ± 0.118 | 0.534 ± 0.114 | 0.538 ± 0.115 | 0.539 ± 0.118 |

| urban | 0.579 ± 0.129 | 0.570 ± 0.129 | 0.580 ± 0.131 | 0.573 ± 0.132 |

| all | 0.564 ± 0.126 | 0.556 ± 0.124 | 0.564 ± 0.127 | 0.560 ± 0.128 |

| Partial index | Class of Financial Situation Assessment | All Households (2018–2022) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Very High | High | Medium | Low | ||

| real equivalent income (PLN/equivalent unit) | 8953 | 4881 | 2948 | 1470 | 3645 |

| real equivalent consumption expenditures (PLN/equivalent unit) | 4423 | 2980 | 1835 | 1359 | 2250 |

| savings rate (%) | 45.2 | 33.6 | 30.5 | −2.0 | 28.9 |

| share of food and non-alcoholic beverages in consumption expenditures (%) | 16.3 | 24.4 | 34.7 | 41.0 | 31.3 |

| share of housing and energy in consumption expenditures (%) | 9.9 | 15.2 | 22.2 | 28.1 | 20.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Wołoszyn, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Oliveira, A.; Oliveira, T. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Financial Situation of Rural and Urban Households in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198516

Głowicka-Wołoszyn R, Wołoszyn A, Stanisławska J, Oliveira A, Oliveira T. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Financial Situation of Rural and Urban Households in Poland. Sustainability. 2024; 16(19):8516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198516

Chicago/Turabian StyleGłowicka-Wołoszyn, Romana, Andrzej Wołoszyn, Joanna Stanisławska, Amílcar Oliveira, and Teresa Oliveira. 2024. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Financial Situation of Rural and Urban Households in Poland" Sustainability 16, no. 19: 8516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198516

APA StyleGłowicka-Wołoszyn, R., Wołoszyn, A., Stanisławska, J., Oliveira, A., & Oliveira, T. (2024). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Financial Situation of Rural and Urban Households in Poland. Sustainability, 16(19), 8516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198516