Abstract

The environmental problems caused by carbon emission have become the focus of worldwide attention. Effective control of carbon emissions cannot be achieved without the protection of the rule of law. Environment public interests litigation is a prominent innovation in the judicial system, and its role in supervising the government to perform its regulatory duties on carbon reduction and regulating the carbon emission behaviors of enterprises and the public deserves discussion. The paper selected the panel data from 274 prefecture-level cities from 2013 to 2021 and analyzed the impact of a procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy on carbon emission control by using the double difference method. The research found that the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy can effectively curb carbon emissions. Heterogeneity analysis showed that in cities with relatively low level of green innovation, the negative correlation between procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies and carbon emissions is more significant. Compared with the eastern region, in the central and western regions, especially in the central region, where the concept, policy, and funding of carbon emission governance are relatively weak, the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation had a more obvious effect on carbon emission governance. Mechanism tests showed that procuratorial public interest litigation policies reduce carbon emissions by reducing energy consumption and increasing public participation in environmental protection. The study will provide an empirical basis for the carbon emission reduction effect on pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation and will offer certain theoretical recommendations for improving the procuratorial public interest litigation system in the ecological environment field.

1. Introduction

In the process of urbanization in recent years, the burning of fossil fuels, automobile exhaust emissions, and deforestation have intensified, and carbon dioxide emissions have risen sharply. The environmental problems caused by this have become a major issue of global and national concern. From the perspective of global carbon emissions in the past ten years, China’s total carbon emissions have been in the forefront and are increasing year by year. The Climate Change Performance Index Report 2024 (CCPI2024) evaluates and compares the climate change performance of the European Union and 63 countries and regions (which together account for more than 90% of global greenhouse gas emissions). China scores 45.56 points, ranking 51st. The overall evaluation of climate change performance is “low”, and both greenhouse gas emissions (40% weight) and energy efficiency (20% weight) scored “very low” [1]. In order to control carbon emissions, the Chinese government proposed the dual control target of carbon reduction to achieve carbon peak and carbon neutrality at the general debate of the seventy-fifth session of the United Nations General Assembly in 2020. In recent years, the Chinese government has not only continued to promote national cooperative emission control actions, but also spared no effort to carry out carbon emission reduction practices at the national, regional, and industrial levels, such as the establishment of a national carbon emission trading market, the implementation of low-carbon cities, and the launch of procuratorial public interest litigation. Have these practices achieved the desired carbon reduction effects? The paper takes the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation as the research object, focusing on the effect of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emission reduction.

Environmental public interest litigation plays an important role in supervising the government to fulfill its duty of carbon reduction regulation and regulating the carbon emission behavior of enterprises and the public, and has attracted increasing attention. It has been hailed as one of the most persuasive, dazzling, and sustained innovations in modern environmental law [2]. As early as the beginning of the century, the procuratorial organs of Laoling City in Shandong Province and Langzhong City in Sichuan Province had carried out sporadic explorations in the field of environmental public interest litigation [3], and these pioneering judicial practices provided empirical reference for the establishment of the procuratorial public interest litigation system. In 2014, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee proposed to “explore the establishment of procuratorial organs to file public interest litigation system”, providing top-level policy guidance for the procuratorial public interest litigation system. In July 2015, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress adopted the Decision on Authorizing the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to Carry out Pilot Work of Public Interest Litigation in Some Regions, authorizing the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to carry out pilot work of public interest litigation in the field of ecological environment and resource protection for a period of two years. The pilot areas are 13 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government), including Beijing, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Jiangsu, Anhui, Fujian, Shandong, Hubei, Guangdong, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, and Gansu. On the basis of summarizing the two-year pilot work experience, it has successively promulgated provisions such as Article 55, paragraph 2, of Civil Procedure Law (2017), Article 25, paragraph 4, of Administrative Procedure Law (2017), and Interpretation of Several Issues concerning the Application of Law to Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation Cases issued together by the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. A public interest litigation system has been jointly established in the field of ecological and environmental prosecutions. According to the statistics, by the end of August 2022, acting as the most imperative subject of public interest litigation, procuratorial organs had filed 702,000 public interest litigation cases, of which 353,000 were environmental public interest litigation cases, accounting for more than half of the total [4]. In addition, the court system accepted a total of 1737 environmental public interest litigation cases filed by procuratorial organs in 2018, accounting for 96% of the total number of environmental public interest litigation cases [5]. What is the effect of such a large number of cases on carbon emissions? How does litigation affect carbon emissions? Based on the procuratorial public interest litigation policy during the pilot period (1 July 2015–30 June 2017), the paper intends to discuss the above issues so as to provide theoretical reference for the formulation of scientific and standardized carbon emission control policies.

The content design of the remaining part is as follows: The second part is materials and methods, including literature review, theoretical analysis, and research analysis. The third part is the results, which consists of parallel trend test, robustness test, heterogeneity analysis, and mechanism test. The fourth part is discussion, analyzing research results and interpreting the underlying reasons. The fifth and final part is the conclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

The paper intends to review the existing research on procuratorial public interest litigation and carbon emissions from levels of both qualitative research and quantitative research.

2.1.1. Qualitative Research

The present research can be divided into three branches. The first one focuses on the effect of procuratorial public interest litigation practice on carbon emissions. Scholars discussed the carbon sink subscription system as a way to assume responsibility for carbon-related litigation [6], demonstrated the internal logic, application, and future path of judicial and administrative synergies in litigation-related litigation [7], and proposed the establishment of a special carbon-related procuratorial public interest litigation system [8]. The second is the theoretical basic research on carbon prosecutorial public interest litigation, exploring how to improve the litigation system [9] and construct a more appropriate litigation model [10,11]. The third is the empirical research on the effect of litigation on carbon emissions and environmental governance. Some scholars conducted a descriptive analysis of the cases, which initially confirmed the positive effect of procuratorial public interest litigation on environmental governance [12] and promoted the new pattern of multiple protections of environmental public interests [13]. Some scholars found that selective handling and case making existed in practice, and questioned the effect of litigation [14].

Existing qualitative studies have provided a basic theoretical perspective for exploring the relationship between procuratorial public interest litigation and carbon emissions, but most of them focused on the discussion of the ought-to-be status, and few dipped into the actual status. Although some studies carried out preliminary quantitative analysis through case interpretation and descriptive statistics, they stopped at the review of the current situation. The mechanism and impact of procuratorial public interest litigation policies on carbon emissions lacked objective and in-depth discussion, and the research reliability and validity were worth examining.

2.1.2. Quantitative Research

Some scholars explored the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation in the field of ecological environment through quantitative research. Chen et al. used the double difference analysis method to analyze the difference in the effect of environmental pollution control before and after the pilot examination of procuratorial administrative public interest litigation, taking industrial wastewater and sulfur dioxide emissions as explanatory variables [15]. Liu et al. used the data of prefecture-level cities from 2010 to 2018 to study the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies on urban environmental governance performance [16]. Zhang et al. took the number of green patents as the explained variable to measure the level of regional green innovation, selected the panel data of 281 prefecture-level cities and A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2017, and used the triple difference analysis method to explore the impact of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation on the level of local green innovation level [17]. Cao et al. used the fixed-effect model, selected urban air quality as the explained variable to measure the level of environmental governance, took civil public interest litigation filed by three subjects, including procuratorial organs, social organizations, and administrative organs, as the explanatory variable, and used the panel data of 285 cities across the country from 2015 to 2019 to investigate the effect of civil public interest litigation filed by different subjects [18]. Wang et al. constructed an economic model and discussed the mechanism of procuratorial public interest litigation on promoting green innovation of enterprises [19].

Compared with qualitative research, quantitative research is conducive to breaking disciplinary barriers, measuring the data through experiments, investigations, and other methods, inferring and verifying the practical operation effect and causality of legal norms, and comprehensively and objectively presenting the real state of the policy governance effect of procuratorial public interest litigation pilots. However, the above quantitative research has not answered the effect and internal mechanism of procuratorial public interest litigation and carbon emissions, and it is difficult to directly explain the phenomenon studied in this paper, nor can it provide appropriate analytical ideas. First, conventional pollutants or the number of patent applications were often used as explanatory variables in previous studies. Although pollution reduction and carbon reduction have synergistic effects, they are not completely equivalent. Therefore, explanatory variables mentioned above are difficult to accurately analyze and effectively solve the carbon emissions problem under the “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality” target. Environmental public interest litigation aims to protect ecosystem service functions including atmosphere, water, soil, carbon dioxide, and other elements. In the realistic context where climate change litigation has not yet been established, procuratorial public interest litigation system in the field of ecological environment provides new possibilities for carbon emissions reduction research from the level of institutional innovation.

In general, the existing literature provides inspiration and reference for this study from different perspectives. However, as a practical exploration carried out before the establishment of the system, we must ask: what is the impact of the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation in the field of ecological environment on carbon emissions? At present, few scholars have conducted normative and scientific research on this question, which provides the possibility and space for the study of this paper. The possible marginal contributions of this paper are: First, based on the strategic background of the country to achieve the goal of “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality”, the impact of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions was analyzed with the aim of enriching and examining the research literature in the field of procuratorial public interest litigation. Second, based on the perspective of judicial judgment, the multi-disciplinary analysis method is used to sort out the internal relationship between procuratorial public interest litigation and carbon emissions and empirically analyze the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions in order to expand the theoretical system of carbon emissions policy and realize the cross-integration of law, management, economics, and other disciplines.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

This part aims at building a theoretical framework of the relationship between procuratorial public interest litigation and carbon emissions from the dimensions of public goods theory, public trust theory, and state obligation theory.

2.2.1. Public Goods Theory

According to the definition of economist Paul A. Samuelson, public goods are shared by members of society, and the use of any member will not diminish the value of other members’ enjoyment of the public goods [20]; that is, any member of society is non-competitive in the consumption of public goods and non-exclusive in the benefit of public goods. In this sense, the ecosystem, which includes elements such as atmosphere, water, soil, and carbon dioxide, represents the basic needs for the survival of any social member and has a typical public nature. Undoubtedly, the ecosystem belongs to the category of public goods, which is related to the fundamental interests of any member of society. According to the economic man hypothesis theory of British economist Adam Smith, private economic subjects such as enterprises and individuals take the pursuit of individual profit maximization as the logical starting point of their behaviors; this makes it difficult for private economic subjects to shoulder the responsibility of providing public goods, and the government, representing the public interests of the state and society, should be the eligible subject. However, as one of the many public goods provided by the government, ecological environmental protection is often shelved or ignored by the government in the process of performing its duties, whether deep or shallow, for the practical consideration of promoting local economic development and managing social life. At this time, it is a scientific and feasible choice to maintain the ecosystem service function by a supervisory, neutral, non-profit, and professional institution or organization [21]. As the legal supervision organ stipulated in Article 134 of the Constitution of China, the procuratorial organ is the best qualified subject to meet the above requirements.

2.2.2. Public Trust Theory

The notion of public trust can be traced back to the ancient Roman concept of “res communes” [22]: By natural law, these things are common property of all: air, running water, the sea, and with it the shores of the sea. It can be seen that the concept of “res communes” has been endowed with public property from the beginning of its birth, and accordingly, the public trust theory formed from this concept has become the legal theoretical basis for protecting social public interests. This concept gradually formed the public trust theory through English common law, and was introduced in the field of environmental law by Professor Joseph L. Sax of the University of Michigan, and then was applied to about 100 cases in more than half of the states in the United States in the 15 years since 1970. According to Professor Sax, the application of public trust theory to protect natural resources and ecological environment must meet the following three conditions: First, it must contain some concept of a legal right in the general public; Second, it must be enforceable against the government; Third, it must be capable of an interpretation consistent with contemporary concerns for environmental quality [23]. With the development of the times and the changes of the environment, the scope of public trust theory has gradually expanded from the navigable waters and riverbeds contested in the case of Illinois Central Railway Company v. Illinois State Government to the ecosystem covering public land, wildlife, atmosphere, water, soil, carbon dioxide, and other elements. The subject also experienced the evolution from the initial private subject suing the government for illegal acts to the government suing the private subject after the 1970s [24]. Therefore, the evolving public trust theory lays out the theoretical basis for environmental torts and provides theoretical justification for procuratorial organs filing public interest litigation on behalf of the state.

2.2.3. State Obligation Theory

Article 26 paragraph 1 of the Constitution stipulates that the State shall protect and improve the living and ecological environment, prevent and control pollution as well as other public hazards. As a solemn oath of the state obligation to protect the environment, this clause is not only the fundamental responsibility of the “promising state” by way of performing its duties to protect the environment, but also the basic right of the civil society to supervise the environmental governance of the “limited state”. The Opinions on Giving Full Play in Judicial Functions to Provide Judicial Services and Guarantee for Promoting Ecological Civilization Construction and Green Development issued by the Supreme People’s Court in 2016 stressed the need to actively explore judicial responses to climate change and hear cases related to carbon emissions in accordance with the law. In December 2023, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and The State Council jointly issued the Opinions on Comprehensively Promoting the Construction of a Beautiful China, further proposing to improve public interest litigation and strengthen judicial protection in the field of ecological environment. These top-level designs have concretized the state environmental protection obligations and provided policy guidance for procuratorial organs to initiate public interest litigation in the field of carbon emissions.

Based on the above analysis, the research hypothesis of this paper is put forward: procuratorial public interest litigation can effectively inhibit carbon emissions.

2.3. Research Design

2.3.1. Model Setting and Variable Definition

The paper uses different-difference method (DID) to evaluate the impact of the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions. The following model is designed for hypothesis testing:

Wherein, the explained variable represents the carbon emission intensity of pilot city i in year t. represents the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation, which is the explanatory variable of this paper. represents the control variable. In addition, in order to eliminate the interference of unobserved factors such as pilot city and year on the regression results, this paper also uses the two-way fixed effect model to conduct empirical research, with representing the time fixed effect, representing the region fixed effect, and ε representing the random disturbance term.

- 1.

- Explained Variable ()

The explained variable of this paper is carbon emission. Referring to the research of Song et al. [25], the paper uses carbon emission intensity (i.e., carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP) to measure the explained variable.

- 2.

- Explanatory Variable ()

The explanatory variable in this paper is the pilot policy of procuratorial administrative public interest litigation system, which is the cross-multiplying term of the virtual variable

and , indicating whether city i implements the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation in year t. If the pilot policy is implemented, the value is 1; otherwise, the value is 0; β0 represents the constant term; β1 represents the policy effect, and since the pilot period is only two years, the policy effect is short-term. During the study sample period, if city i is selected as the pilot city of procuratorial public interest litigation system, the value of is 1; otherwise, the value is 0. When the observed value of the sample occurred after the year when the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy began (that is, 2015 and later), the value of

is 1; otherwise, the value is 0.

- 3.

- Control Variables

With reference to the research [26,27], this paper selects and determines the following control variables: the sum of word frequency related to “carbon emission” in the Government Work Report, the proportion of energy conservation and environmental protection expenditure in fiscal expenditure, the number of Internet broadband access users, the green space area of municipal districts, the added value of secondary production, and the level of foreign investment. Details of each variable are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definition and calculation method.

2.3.2. Sample Selection and Data Sources

In view of the availability of data, 274 prefecture-level cities (excluding Beijing, Tianjin, Chongqing, and Shanghai) from 2013 to 2021 are selected as research samples to explore the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies on carbon emissions. Carbon emission data were obtained from China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Urban Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Agricultural Statistical Yearbook, China Animal Husbandry Yearbook, and China Forestry and Grassland Statistical Yearbook. The word frequency data of the Government Work Report related to carbon emissions came from the work reports of municipal governments at various levels. Data for other variables were obtained from the local Statistical Yearbook.

In accordance with the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Authorizing the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to Carry out the Pilot Work of Public interest Litigation in Some Regions, the provisions of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate’s promulgation of the Pilot Plan for the Reform of Public Interest Litigation by Procuratorial Organs, as well as judgment documents and typical cases issued by the central and local people’s courts and procuratorates, etc., a total of 73 pilot cities (including municipalities directly under the Central Government) were selected in this study, and the specific list is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of pilot cities for procuratorial public interest litigation.

2.3.3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the main variables. As shown in the table, the mean value of carbon emission intensity (Carbon) is 10.30527, the standard deviation is 6.676426, and the minimum and maximum values are 1.11108 and 39.9724, respectively, indicating that China’s carbon emission is at a relatively high level and not optimistic, and the carbon emission intensity varies greatly among cities. The mean Greenery area of urban districts is 8.384577, the standard deviation is 0.9206883, and the minimum and maximum are 5.988961 and 11.90861, respectively, which shows that the national greenery level is good, but greenery area varies considerably among cities. In the Government Work Report, the minimum and maximum values of the sum of word frequency (Government) related to carbon emission are 3 and 136, respectively, and the standard deviation is as high as 18.77044, indicating that some city governments are not satisfactory in the duty performance of carbon emission. Meanwhile, there are great differences in the importance of carbon emission supervision among various city governments. The average value is 46.07851, which reflects the overall good performance of the government in carbon emission supervision under the guidance of a series of low-carbon policies introduced by the country. In addition, the proportion of expenditure on energy conservation and environmental protection to total fiscal expenditure (Expenditure), the number of Internet broadband access users (Internet), the level of foreign investment (FDI), and the added value of secondary production (Industry) are quite different.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Parallel Trend Test

The test results are shown in Table 4. The estimated coefficients of two years before the pilot implementation (pre_2) and one year before the pilot implementation (pre_1) are not significant, indicating that the premise of using the differential difference model is satisfied through the assumption of parallel trend. In terms of the dynamic effect, both the value and significance of the estimated coefficient have increased since 2015, which indicates that the carbon emission intensity of each city shows a downward trend with the gradual promotion of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation.

Table 4.

Parallel trend test.

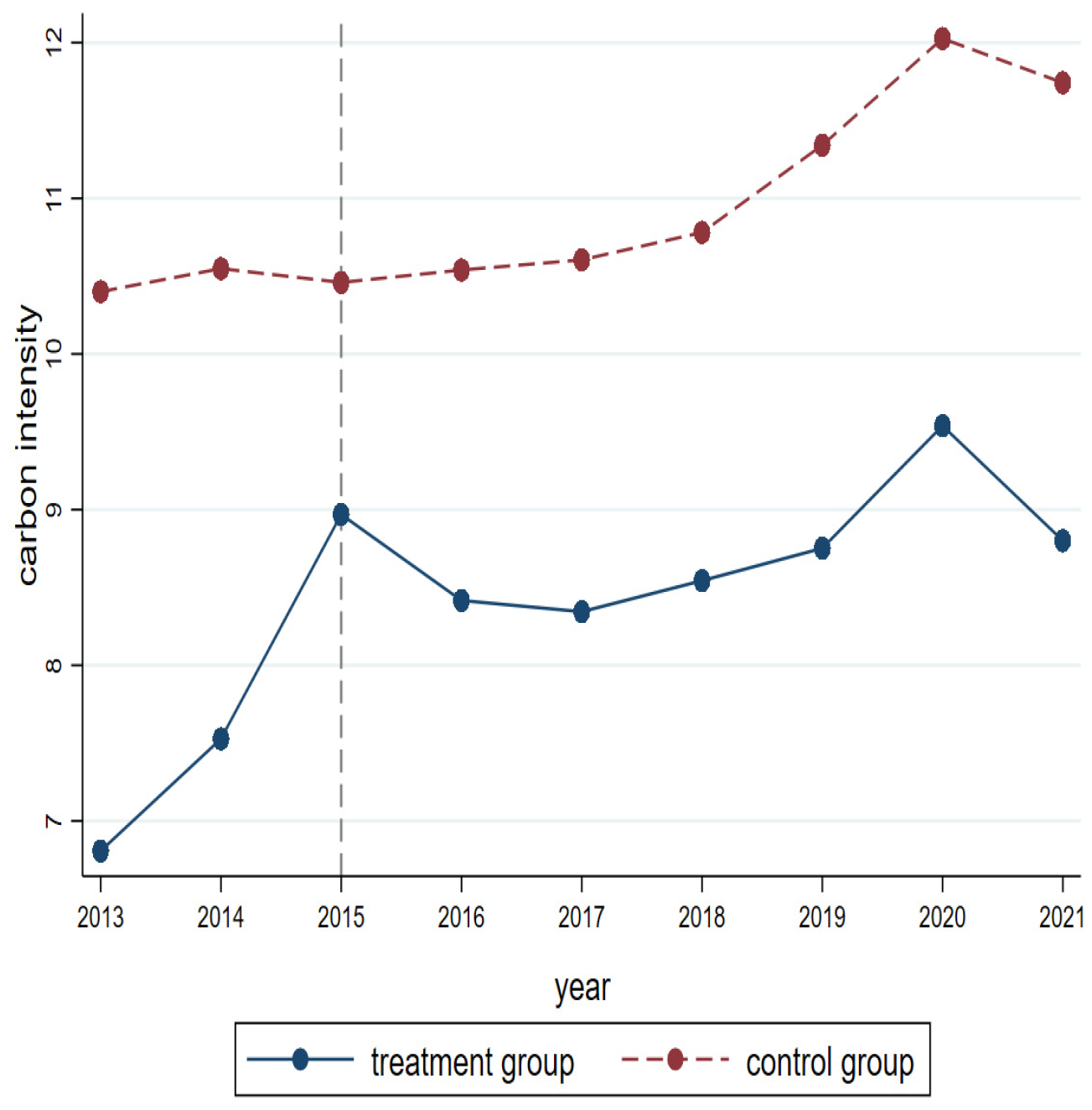

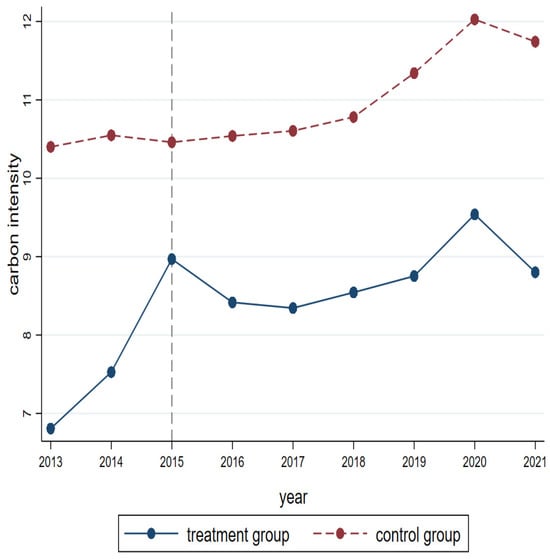

As shown in Figure 1, before 2015, the year of policy implementation, the change trend of carbon emission intensity in the treatment group and the control group was generally the same. Specifically, the annual average of 2013–2014 showed an upward trend, and the increase rate of the treatment group was larger than that of the control group. From 2014 to 2015, the carbon emission intensity of the control group showed a small decrease, while that of the treatment group showed a continuous upward trend. Therefore, it can be preliminarily judged that the time trend assumption of the treatment group and the control group before the policy implementation year was basically satisfied. In 2016 and 2017, after the implementation of the policy, the carbon emission intensity of the treatment group showed a significant downward trend, while that of the control group increased slowly. After the end of the pilot in 2017, the carbon emission intensity of the treatment group also increased. The basic judgment of the difference in the trend lines after the implementation year of the policy was caused by the pilot procuratorial public interest litigation policy. Of course, this conclusion is not robust, and further testing of the dynamic effect between the two is needed.

Figure 1.

Time trend chart.

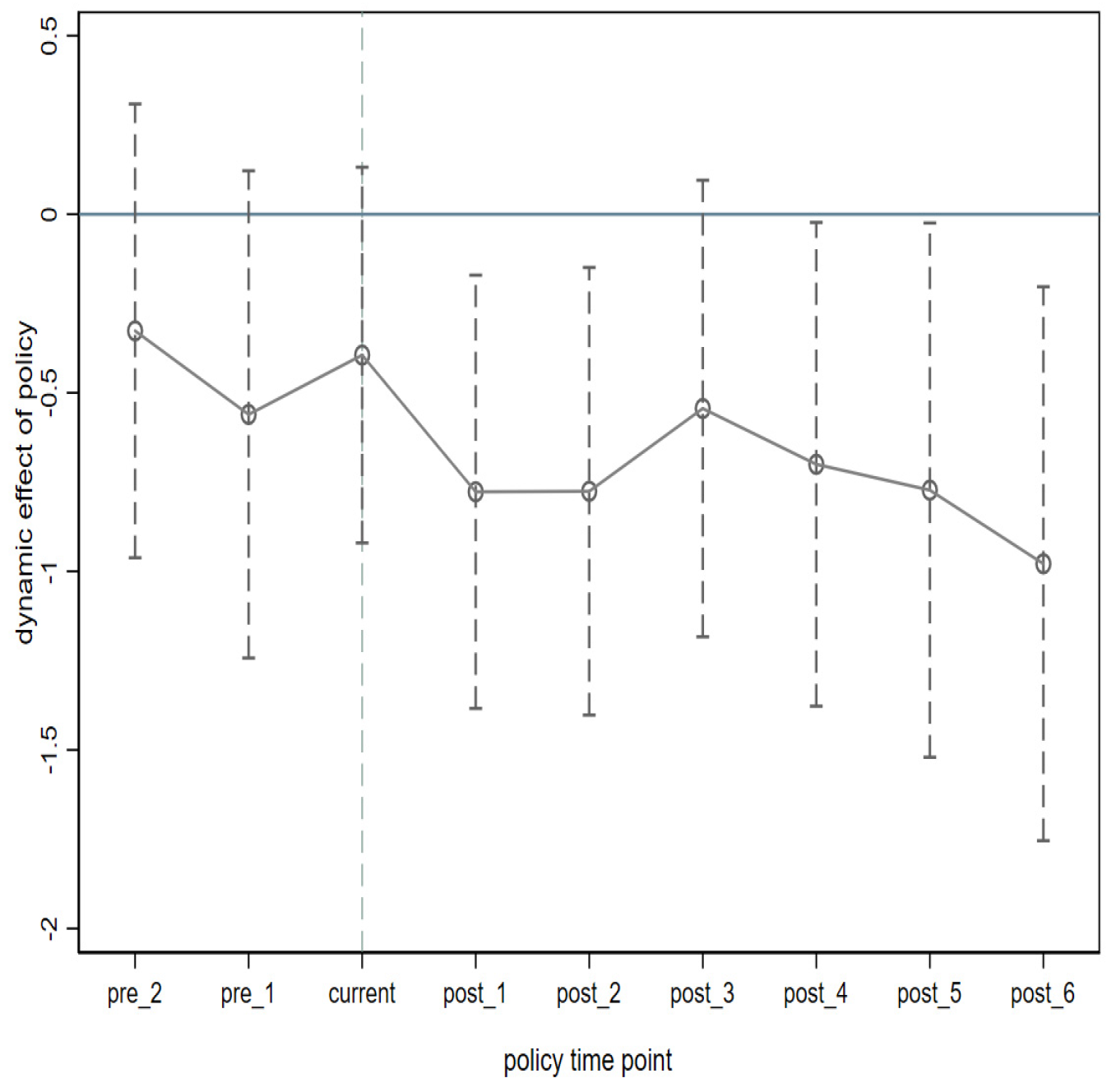

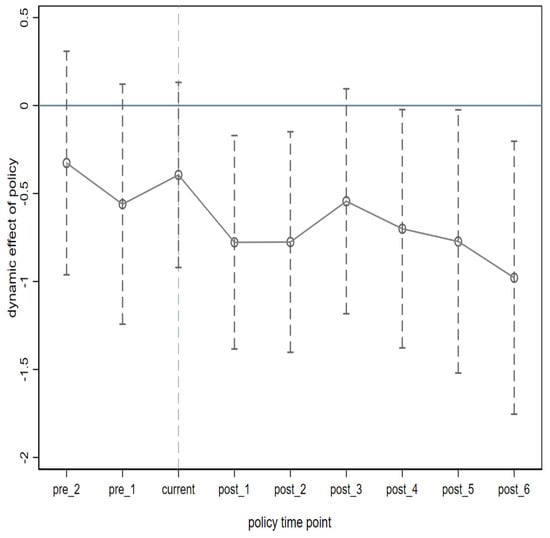

In Figure 2, the covered short line perpendicular to the horizontal axis is the 95% confidence interval for the regression coefficient of the cross term between each period number and the dummy variable of the processing group. It can be seen that the coefficients for the first two years of policy implementation are not significant (95% confidence interval contains a horizontal dotted line with coefficient = 0), which is basically consistent with the information revealed in Figure 1. The coefficient in 2015, the year of the policy implementation, is not significant, indicating that the impact of the policy has a certain time lag. However, in the years after the policy implementation, except for 2018, which is slightly not significant, the coefficient in the other years is basically significant, and the policy has the greatest effect in the sample period 2016–2017. The reason why the coefficient in 2018 is not significant may be that after 2018, procuratorial organs conducted exploration of public interest litigation cases in other fields except the ecological environment field, such as minors’ personal information, cultural heritage, juvenile protection, etc., resulting in a limited increase in the proportion of environmental public interest litigation cases handled by supervisory organs related to carbon emissions, and even showed a trend of decline. Accordingly, its impact on carbon emissions is also diminishing.

Figure 2.

Dynamic effect test diagram.

3.2. Benchmark Regression

Table 5 lists the regression results of the implementation of the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy on carbon emissions. The regression results show that the implementation of the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy has effectively reduced carbon emissions. It can be seen from column (1) that the estimated coefficient of DID is −0.445, which is highly significant at the level of 1%. After adding control variables, as shown in column (2), the coefficient of DID is still significantly negative at the level of 5%. This result also confirms the hypothesis of the analysis in this paper—the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation can effectively curb carbon emissions.

Table 5.

Baseline regression.

3.3. Robustness Test

3.3.1. Placebo Test

First, this paper constructs a virtual treatment group and a control group through random sampling and uses a difference-in-differences model for regression. The results of regression are shown in column (1) of Table 6. As can be seen from Table 6, DID items are not significant. Second, this paper conducts a placebo test by fictionalizing policy implementation time. Assuming that the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation has been implemented since 2016, the results after regression are shown in column (2) of Table 6, and the coefficient of DID of the cross-multiplying term is not significant. This indicates that the reduction of carbon emissions in the pilot cities is not caused by unobservable factors, but by the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation. This result further verifies the robustness of baseline regression.

Table 6.

Robustness check.

3.3.2. Changing Sample Scope

In this paper, the provinces that have not implemented the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation are excluded, and the sample scope is reduced to 73 pilot cities that have implemented the pilot policy in 13 pilot provinces (see Table 2) and 71 non-pilot cities that have not implemented the pilot policy in above 13 pilot provinces. In total, the regression is carried out in 143 cities. The results are shown in column (3) of Table 6. The DID coefficient is −0.394, which is still significantly negative at the significance level of 5%, that is to say, the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation significantly reduces the carbon emission intensity of the pilot cities, therefore, it also verifies that the baseline regression results of this paper are robust.

3.3.3. Replacing Explained Variables

As mentioned above, when calculating the carbon emission of the explained variable, this paper takes reference from previous studies and uses carbon emission intensity, that is, carbon dioxide emission per unit GDP, as a proxy variable to conduct a basic regression test, and the test results are significant. In order to avoid the experimental error caused by the choice of the measurement method of the dependent variable, the robustness test will be carried out by replacing the explained variable. With reference to existing studies, this paper sets per capita carbon emission [28] instead of the original explained variable to conduct a new round of empirical test, and the test results are shown in column (4) in Table 6. It is not difficult to find that the DID coefficient is still significantly negative at the significance level of 10%, and the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation significantly inhibits carbon emissions.

3.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

3.4.1. Heterogeneity Analysis of Green Innovation Level

Previous studies have shown that the level of green innovation has an impact on carbon emissions [29]. The original value of the number of green patent grants in different cities is selected as the proxy variable of green innovation (variable symbol is Innovation), and the samples are also divided into high and low groups according to the median number of green patent grants, as shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7. Regardless of whether the number of green patents granted in each city is large or small, the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation significantly inhibits the carbon emissions of the city, and the significance coefficient of the city with a small number of green patents granted is much smaller than that of the city with a large number of green patents granted.

Table 7.

Green innovation level and regional heterogeneity analysis.

3.4.2. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

According to the division of “three zones” in the annual data of the National Bureau of Statistics by province, the sample cities were divided into three regions, eastern group, central group, and western group, and the heterogeneity of procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies in different regions was analyzed as follows: the eastern group included Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan (11 provinces); the middle group includes Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, and Jiangxi (8 provinces), and the western group includes Inner Mongolia, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang (11 provinces). According to the regression results, the DID coefficients of column (3) Eastern region and column (5) Central region are significantly negative at the 10% level, and column (4) Western region is significantly negative at the 5% level, indicating that the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation has the best effect in the central region, followed by the western region, and finally the eastern region.

3.5. Mechanism Test

The internal impact mechanism of procuratorial public interest litigation policy on curbing carbon emissions can be examined in terms of reducing energy consumption (Consume) and enhancing public participation in environmental protection (Public). On the one hand, the warning and deterrent function of litigation forces the government to strengthen local environmental regulations and enterprises to improve production technology and environmental protection technology to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions. On the other hand, the publicity and education effect brought by the lawsuit can enhance the public awareness of low-carbon consumption and thus reduce carbon emissions. Based on above analysis, the paper constructs an intermediary effect model to test the mechanism of procuratorial public interest litigation policies affecting carbon emissions. The regression equation is as follows:

Among them, M represents two intermediary variables: public participation in environmental protection and energy consumption. Referring to previous studies, Baidu search index [30] “carbon emissions” and total energy consumption [31] will be used respectively. For reference to the research of Barton and Kenny [32], Formula (1) tests the total effect of the core explanatory variable “procurating public interest litigation policy” on “carbon emission” as the explained variable; Formula (2) tests the direct effect of core explanatory variable on the intermediary variables; and Formula (3) tests the common effects of core explanatory variable and intermediary variables on the explained variable. When the coefficients θ1, β1, and γ2 are all significant, if γ1 is not significant, it indicates that intermediary variable M has a complete mediation effect, and if γ1 is significant, it indicates that intermediary variable M has a partial mediation effect.

Table 8 shows the results of the mediation effect test, and column (1) contains the results of the baseline regression. Columns (1), (2), and (3) test the mediating effect of public participation in environmental protection. In column (2), the coefficient of procuratorial public interest litigation policy is significantly positive, and the coefficient is large, indicating that procuratorial public interest litigation policy can significantly enhance public participation in environmental protection. In column (3), the coefficient of public participation in environmental protection is highly significant and negative at the significance level of 1%, illustrating that public participation in environmental protection can effectively reduce carbon emissions. In column (1) and column (3), the procuratorial public interest litigation policy is significantly negative at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively, and the direct effect after controlling the intermediary variables is smaller than total effect, indicating that the indirect effect and total effect are opposite in the direction of action, and there is a partial intermediary effect. From the overall effect, the procuratorial public interest litigation policy significantly reduces carbon emissions, and, to a large extent, it reduces carbon emissions by increasing public participation in environmental protection.

Table 8.

Mechanism test.

Columns (1), (4), and (5) are mediating effect tests of energy consumption. In column (4), the coefficient of procuratorial public interest litigation policy is highly significantly negative at the level of 1%, indicating that the policy has effectively reduced energy consumption. In column (5), the coefficient of procuratorial public interest litigation policy is also highly significantly negative at the level of 1%, and the energy consumption coefficient is significantly negative at the level of 5%, that is, policy implementation and reduction of total energy consumption can effectively curb carbon emissions. After controlling explanatory variables, the coefficient of intermediary variable is still significant. Considering the total effect of (1), procuratorial public interest litigation policy effectively reducing carbon emissions, there is a partial intermediary effect on energy consumption, that is, the implementation of the policy effectively reduces carbon emissions by reducing total energy consumption.

4. Discussion

By using the double difference method, the paper analyzed the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy on carbon emissions. The research found that the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy can effectively curb carbon emissions. Heterogeneity analysis showed that in cities with relatively low level of green innovation, the negative correlation between procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies and carbon emissions is more significant. The reason may be that cities with a large number of green patents have often achieved a relatively controllable level of carbon emissions through a higher level of green technology innovation. At this time, when the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation is implemented in these cities with relatively rich ecological background, it is often difficult to achieve a significant effect immediately. For those cities with low level of green innovation and more emphasis on extensive economic growth mode that consumes energy, the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation can usually make up for the shortcomings at the technical level in time, so as to produce more significant policy effects and effectively curb carbon emissions.

Compared with the eastern region, in the central and western regions, especially in the central region, where the concept, policy, and funding of carbon emission governance are relatively weak, the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation has a more obvious effect on carbon emission governance. The possible reasons are as follows: The eastern coastal region has been leading the country for a long time in terms of the government’s ecological and environmental governance concepts, policies, funds, and other investment levels, as well as the carbon emission cognition of enterprises and the public. Taking 2015, the first year of implementation of the pilot policy, as an example, the completed investment in industrial pollution control in the eastern region reached CNY 42.44168 billion, followed by the western region, where the total amount is CNY 18.224.57 billion, and the eastern region, where the amount is the least, CNY 16.7016.4 billion. Therefore, the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation, as one of the series of combined policies of the government, enterprises and the public to deal with carbon emission control, has little significant impact in the eastern region. However, the initial level of carbon emission governance in the central and western regions, especially in the central region, is relatively low, and the policy catch-up effect is significant. In the case of relatively weak carbon emission control concepts and investment efforts, the implementation of the pilot policy of procuratorial public interest litigation has a more obvious effect on carbon emission control in the central region.

Based on the above research, the paper puts forward the following policy suggestions: we should keep the judicial modesty while supervising the judicial administration. Inaction of administrative organs is the cause of procuratorial organs to file environmental administrative public interest litigation cases. Procuratorial organs have incorporated administrative acts into the scope of judicial supervision through measures such as making and issuing pretrial procuratorial recommendations and initiating lawsuits, which have corrected administrative organs’ negligence in performing their duties, inadequate performance of their duties, and illegal performance of their duties to a large extent. At the same time, we should adhere to the principle of administrative priority and judicial modesty so as to avoid excessive activism and reinforcement of the judiciary and restrict the proper play of the administrative power. Procuratorial organs should avoid the phenomenon of excessive interference with the executive power, respect the operation rules of the executive power, follow the procedure requirements, and achieve accurate supervision.

In addition, public participation should be strengthened. We should give full play to the neutral, professional, and public welfare functions inherent in social organizations, and pass on the public’s demands to administrative organs through democratic consultations such as symposiums and participation in the deliberation and administration of state affairs so as to realize scientific and democratic decision-making. At the same time, new media platforms should also be used to intensify publicity on the types, subjects, causes, procedures, and other contents of procuratorial public interest litigation, reward the public who provide case clues in a timely manner, expand the number and scope of public hearing cases according to law, and strengthen the public’s attention to procuratorial public interest litigation.

The research expands and enriches theoretical results and practical insights on the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions. The main contribution of this study lies in that it demonstrates the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions, expands the theoretical basis of China’s carbon emission reduction policy, provides operable ideas and schemes for functional departments to optimize procuratorial public interest litigation policies, and helps to deepen the theoretical research on carbon emission regulation from the judicial perspective, thus realizing the intersection and integration of law, economics, management, and other disciplines.

Limited by the availability of research data, this paper only analyzes the impact of procuratorial public interest litigation on carbon emissions from a municipal perspective. With the deepening of the research, ways to conduct research on differences based on different types of procuratorial public interest litigation in the field of ecology and environment is the direction of subsequent research.

5. Conclusions

Using 274 prefecture-level cities from 2013 to 2021 as research samples, this paper empirically studies the effect of procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policies on carbon emission control by using the double difference analysis method. The results show that the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy has a negative impact on carbon emissions, and this conclusion remains valid after robustness tests such as random sampling, fabricating policy time, changing sample scope, and replacing explained variables, indicating that the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy can effectively restrain carbon emissions and promote the realization of the “carbon neutral and carbon peak” goal. By further exploring the mechanism of the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy on carbon emissions, it is found that, possibly due to the catch-up effect, the procuratorial public interest litigation pilot policy has a more significant effect on carbon emissions governance in areas with relatively low green innovation level and relatively weak investment in carbon emission governance concepts, policies, and funds. Mechanism tests showed that procuratorial public interest litigation policies reduce carbon emissions by reducing energy consumption and increasing public participation in environmental protection. Accordingly, policy suggestions on improving the procuratorial public interest litigation system in the field of ecological environment were put forward.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and Z.S.; Methodology, L.P.; Project adminstration, Z.L.; Formal analysis, J.S.; Software, Z.S.; Writing, J.S.; Data curation, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Major project of National Social Science Foundation (22&ZD107) and Soft Science Research Project of Shaanxi Province (2023-CX-RKX-108).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Available online: https://ccpi.org/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Thompson, B.H., Jr. The Continuing Innovation of Citizen Enforcement. Univ. Ill. Law Rev. 2000, 1, 185–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.K.; Tao, B.J. Double Observation of Procuratorial Organs Participating in Environmental Public Interest Litigation—On the Improvement of Article 55 of the Civil Procedure Law. Orient. Law 2013, 5, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/2022zgjxwfbhkdsl/202209/t20220922_597013.shtml (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Liu, Y. Development Trend and System Improvement of Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation System in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on 2017–2019 Data. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 4, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, J.; Xiong, X.F.; Wang, X. Research on the Judicial Application of Carbon Sink Subscription under the Background of “Dual Carbon”—Based on 40 Ecological Environmental Litigation Cases. Sichuan Environ. 2024, 3, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.J.; Li, J. Judicial and Administrative Coordination Mechanism to Achieve the Goal of “Double Carbon” from the Perspective of Judicial Protection. J. Yantai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 4, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Erdenbagen. Carbon Peaking Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation Legalizatio. J. Cent. South Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.Y. Construction of Public Interest Litigation System under the Goal of “Double Carbon”. Politics Law 2022, 2, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Climate Justice Research on “Moderate Activism” in China under the Background of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality: Extraterritorial Practice and Realization Path. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 2, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. The judicial Approach of Climate Change Litigation in China under the “Double Carbon” Goal. Environ. Prot. 2023, 6, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.P.; Zhou, H.J. Reflection on “Nationalization” of Public Interest Litigation. North. Leg. Sci. 2019, 6, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Q. Comparative Study of Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation. J. Natl. Prosec. Coll. 2019, 1, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.J.; Wang, G.P. The Formation and Pattern of Social Organizations Filing Environmental Administrative Public Interest Litigation. Inn. Mong. Soc. Sci. 2023, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.H.; Shao, J.S.; Wang, X.C. The Effect Test and Improvement Path of Procuratorial Administrative Public Interest Litigation System—An Empirical Analysis Based on Differential Method. Peking Univ. Law J. 2020, 5, 1328–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Fan, W.Y. Does Public Interest Litigation Improve A City’s Environmental Governance Performance?—Empirical Research Based on Micro-data of 287 Prefecture-level Cities. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2021, 4, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Fan, W.Y.; Gao, Y. Environmental Justice System Reform and Local Green Innovation: Evidence from the Pilot of Public Interest Litigation. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 10, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Zhi, Y.J. An Empirical Test of the Difference in Effect of Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation Brought by Different Subjects. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.N.; Wang, Y.T. The Impact of Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation on Corporate Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Green Patent Applications. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 6, 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Nordhaus, W.D. Economics, 19th ed.; McGraw Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1971; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Justinian. The Ladder of Jurisprudence; China University of Political Science and Law Press: Beijing, China, 2000; Volume II, pp. 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, J.L. The Public Trust Doctrine in Natural Resource Law: Effective Judicial Intervention. Mich. Law Rev. 1970, 3, 471–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.J. Changing Conceptions of Property and Sovereignty in Natural Resources: Questioning the Public Trust Doctrine. Iowa Law Rev. 1986, 1, 631–716. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, B.B. How Can Environmental Rights Trading Achieve Synergies in Reducing Pollution and Carbon: Theoretical and Empirical Evidence. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2024, 2, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.Y.; Chen, D.K. Haze Pollution, Government Control and High-quality Economic Development. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.R.; Zhang, Z.L.; Deng, W. Government Environmental Expenditure, Budget Management, and Regional Carbon Emissions: Provincial Panel Data from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.K.; Wang, Y.M. The Transformation of Local Government Competition Mode and Carbon Emission Performance: Empirical Evidence from the Work Report of Prefecture-level City Government. Economist 2022, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.H.; Li, H. Carbon Pilot Policies, Green Innovation and Business Productivity. Inq. Econ. Issues 2023, 4, 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.Q.; Wan, G.H.; Sun, W.Z.; Luo, D.L. Public Demands and Urban Environmental Governance. Manag. World 2013, 6, 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Can Pilot Policies of Low-carbon Cities Reduce Carbon Emissions? Evidence from Quasi-natural Experiments. Econ. Manag. 2020, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).