A Typology of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Demographic Correlates and Reasons for Limited Public Engagement in Pro-Environmental Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Correlates of Pro-Environmental Behaviors

3. The Present Study

4. Methods

Measures

- Decide on the sampling frame: who is the target sample of the study?

- Consider the minimum sample size required for the analysis.

- Decide on the contents which make up the construct that is being examined by the study.

- Consider the minimum number of indicators required for a meaningful analysis of subgroups across the construct of relevance.

- Clean the data and examine for missing values and outliers.

- Conduct latent class analysis. For more information on latent class analysis [33].

- Decide on the number of classes based on fit statistics, with lower BIC and AIC indicating improved models (compared with models of fewer classes/profiles). These data are examined against entropy scores, which indicate how well the model defines the classes. A score > 0.8 represents an acceptable solution, while the Lo–Mendell–Rubin test adjusted likelihood ratio is significant. The goal is to reach as few classes as statistically possible.

- Examine the correlates of the new class solution.

5. Results

5.1. The Three-Subgroup Solution

5.2. Bivariate Correlates

6. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: Mitigation of Climate Change. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Van der Linden, S.; Maibach, E.; Leiserowitz, A. Improving public engagement with climate change: Five “best practice” insights from psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, C.; Roelich, K. Psychological barriers to pro-environmental behaviour change: A review of meat consumption behaviours. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quimby, C.C.; Angelique, H. Identifying barriers and catalysts to fostering pro-environmental behavior: Opportunities and challenges for community psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 47, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Elucidating green consumers: A cluster analytic approach on proenvironmental purchase and curtailment behaviors. J. Euromark. 2009, 18, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Khan, A. Prevalence and clustering patterns of pro-environmental behaviors among canadian households in the era of climate change. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.G.; Patel, J.D. Classifying consumers based upon their pro-environmental behaviour: An empirical investigation. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 18, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.H.; Kmec, J. Reinterpreting the gender gap in household pro-environmental behaviour. Environ. Sociol. 2018, 4, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavisakalyan, A.; Tarverdi, Y. Gender and climate change: Do female parliamentarians make difference? Eur. J. Political Econ. 2019, 56, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.O.; Emanuele, R. Male-female giving differentials: Are women more altruistic? J. Econ. Stud. 2007, 34, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccardo, S.; Pietrasz, A.; Gneezy, U. On the size of the gender difference in competitiveness. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Talking past each other? Cultural framing of skeptical and convinced logics in the climate change debate. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarewitz, D. Does climate change knowledge really matter? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennes, E.P.; Kim, T.; Remache, L.J. A goldilocks critique of the hot cognition perspective on climate change skepticism. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 34, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathchandra, D.; Haltinner, K. How believing climate change is a “hoax” shapes climate skepticism in the United States. Environ. Sociol. 2021, 7, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, F.S.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M.; Torabi, E. Can public awareness, knowledge and engagement improve climate change adaptation policies? Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, P.G.; Hornsey, M.J.; Bongiorno, R.; Jeffries, C. Promoting pro-environmental action in climate change deniers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, Ö.H.; López-Sintas, J. Is pro-environmentalism a privilege? Country development factors as moderators of socio-psychological drivers of pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 8, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, A.; Raczkowska, M.; Utzig, M. Pro-environmental behaviour in the European Union countries. Energies 2021, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, J.; Pilloni, M.; Hamed, T.A. A survey of renewable energy, climate change, and policy awareness in Israel: The long path for citizen participation in the national renewable energy transition. Energies 2023, 16, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, L.; Tal, A. Convergence and conflict with the ‘National Interest’: Why Israel abandoned its climate policy. Energy Policy 2015, 87, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Ulitsa, N.; AboJabel, H.; Engdau, S. Older persons’ perceptions concerning climate activism and pro-environmental behaviors: Results from a qualitative study of diverse population groups of older Israelis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, M.; Gabay, O.; Angel, D.; Barneah, O.; Gafny, S.; Gasith, A.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Hershkovitz, Y.; Israel, A.; Milstein, D. Impacts of climate change on biodiversity in Israel: An expert assessment approach. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kácha, O.; Vintr, J.; Brick, C. Four Europes: Climate change beliefs and attitudes predict behavior and policy preferences using a latent class analysis on 23 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M. The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbon, E.; Douglas, H.E. Personality and the pro-environmental individual: Unpacking the interplay between attitudes, behaviour and climate change denial. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 181, 111031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltomme, B.; Gorissen, K.; Weijters, B. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Convergent validity, internal consistency, and respondent experience of existing instruments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, T.J.; Melton, T.N.; Miller, Z.D.; Lawhon, B.; Agans, J.P.; Taff, B.D. A multi-dimensional measure of pro-environmental behavior for use across populations with varying levels of environmental involvement in the United States. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, G.H.; Muthen, B. Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychol. Methods 2005, 10, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, A.L. Basic concepts and procedures in single and multiple group latent class analysis. In Applied Latent Class Analysis; Hagenaars, J.A., McCutcheon, A.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 56–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lubke, G.; Neale, M. Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors with categorical outcomes: Class invariance of parameters of factor mixture models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2008, 43, 592–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermunt, J.K.; Magidson, J. Latent class cluster analysis. In Applied Latent Class Analysis; Hagenaars, J.A., McCutcheon, A.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Ayalon, L. Intergenerational relations in the climate movement: Bridging the gap toward a common goal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCright, A.M. The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A.M.; Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. To select effective interventions for pro-environmental behaviour change, we need to consider determinants of behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, M.; Bruns, H.; DellaValle, N.; Murauskaite-Bull, I. Synergies of interventions to promote pro-environmental behaviors—A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2024, 84, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyeva, T.; Samusevych, Y.; Babenko, V.; Bestuzheva, S.; Bondarenko, S.; Nesterenko, I. Environmental Taxation: Role in Promotion of the Pro-Environmental Behaviour. 2023. Available online: https://repo.btu.kharkov.ua//handle/123456789/22572 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

| Variable Name | Frequency (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 52.11 (19.47) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 324 (50.1%) |

| Education (1–5) | 3.60 (0.96) |

| Pro-environmental behaviors | |

| Reduce energy consumption | 200 (30.9%) |

| Reduce water consumption | 141 (21.8%) |

| Waste recycling | 451 (69.7%) |

| Avoid disposable products | 431 (66.6%) |

| Consume seasonal foods | 127 (19.6%) |

| Consume environmentally friendly products | 265 (41.0%) |

| Use alternative transportation (e.g., public transportation, bicycles) | 146 (22.6%) |

| Purchase a hybrid or electric car | 125 (19.3%) |

| Use renewable energies | 85 (13.1%) |

| Isolate the house | 95 (14.7%) |

| Reasons for lack of engagement | |

| Limited information | 375 (58.0%) |

| Unclear what needs to be done | 367 (57.5%) |

| Do not worry about the changing climate | 118 (18.2%) |

| It is not my responsibility | 80 (12.4%) |

| Model | Loglikelihood | AIC | BIC | Entropy | Mean Probability of Profile Membership | LMR-A p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-subgroup | −3491.06 | 7002.12 | 7046.84 | |||

| 2-subgroup | −3230.27 | 6502.54 | 6596.46 | 0.65 | Subgroup 1: 0.90 | <0.01 |

| Subgroup 2: 0.87 | ||||||

| 3-subgroup | −3167.40 | 6398.79 | 6541.91 | 0.73 | Subgroup 1: 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Subgroup 2: 0.84 | ||||||

| Subgroup 3: 0.88 | ||||||

| 4-subgroup | −3148.14 | 6382.27 | 6547.58 | 0.75 | Subgroup 1: 0.83 | 0.28 |

| Subgroup 2: 0.88 | ||||||

| Subgroup 3: 0.76 | ||||||

| Subgroup 4: 0.89 |

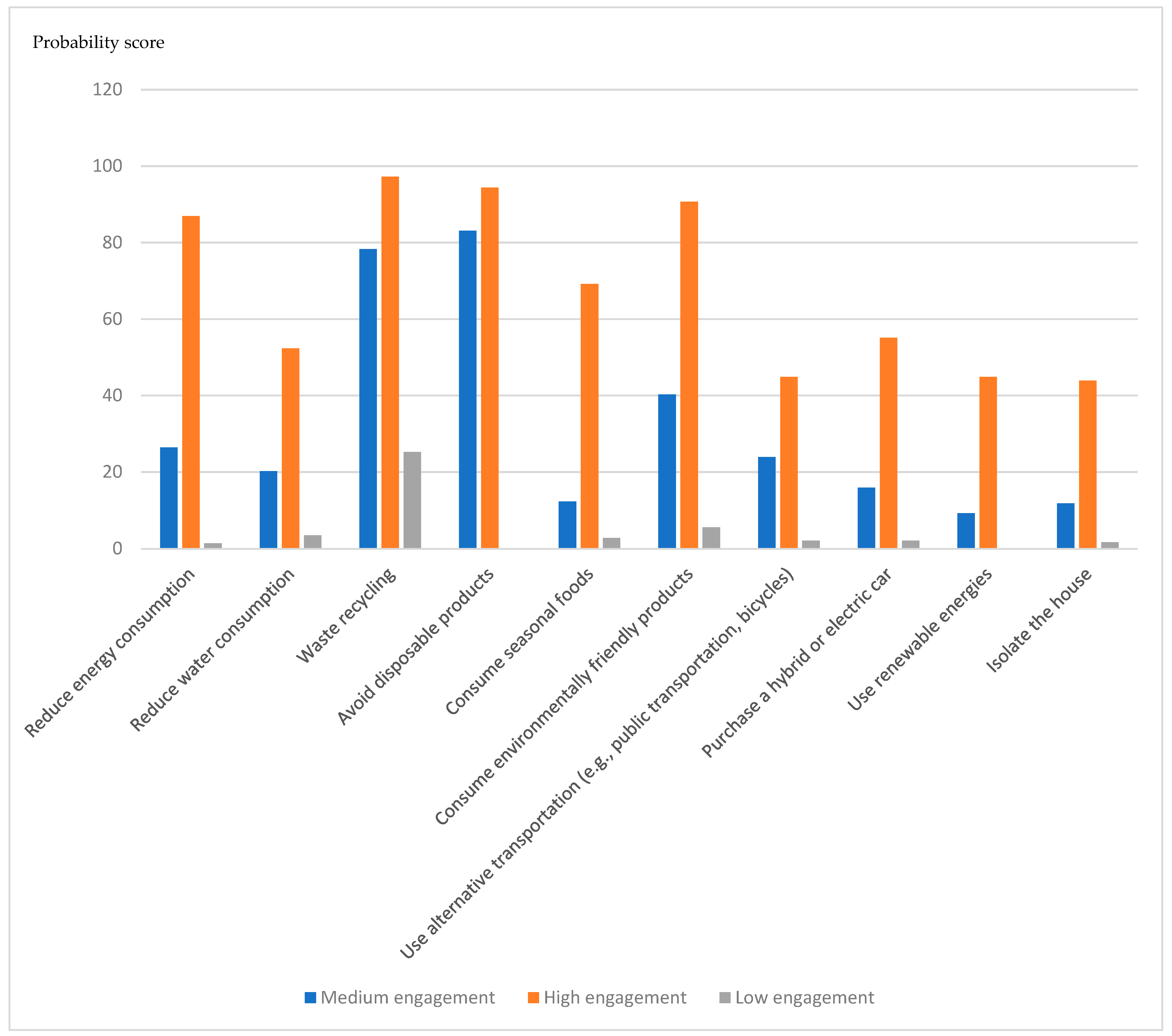

| Pro-Environmental Behavior | Medium Pro-Environmental Engagement (387; 59.8%) | High Pro-Environmental Engagement (113; 17.5%) | Low Pro-Environmental Engagement (146; 22.6%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce energy consumption | 105 (26.4%) | 93 (86.9%) | 2 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Reduce water consumption | 80 (20.2%) | 56 (52.3%) | 5 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| Waste recycling | 311 (78.3%) | 104 (97.2%) | 36 (25.2%) | <0.001 |

| Avoid disposable products | 330 (83.1%) | 101 (94.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Consume seasonal foods | 49 (12.3%) | 74 (69.2%) | 4 (2.8%) | <0.001 |

| Consume environmentally friendly products | 160 (40.3%) | 97 (90.7%) | 8 (5.6%) | <0.001 |

| Use alternative transportation (e.g., public transportation, bicycles) | 95 (23.9%) | 48 (44.9%) | 3 (2.1%) | <0.001 |

| Purchase a hybrid or electric car | 63 (15.9%) | 59 (55.1%) | 3 (2.1%) | <0.001 |

| Use renewable energies | 37 (9.3%) | 48 (44.9%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Isolate the house | 47 (11.8%) | 47 (43.9%) | 1 (0.7%) | <0.001 |

| Medium Pro-Environmental Engagement (387; 59.8%) | High Pro-Environmental Engagement (113; 17.5%) | Low Pro-Environmental Engagement (146; 22.6%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.42 (19.50) | 60.33 (16.90) | 42.31 (17.31) | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 210 (52.9%) | 48 (44.9%) | 66 (46.2%) | 0.19 |

| Education | 3.66 a (0.87) | 3.87 a (0.78) | 3.21 (1.18) | <0.001 |

| Reasons for lack of engagement | ||||

| Limited information | 246 (62.0%) | 70 (65.4%) | 56 (41.3%) | <0.001 |

| Unclear what needs to be done | 239 (60.2%) | 66 (61.7%) | 62 (43.4%) | <0.001 |

| Do not worry about the changing climate | 57 (14.4%) | 14 (13.1%) | 47 (32.9%) | <0.001 |

| It is not my responsibility | 40 (10.1%) | 11 (10.3%) | 29 (20.3%) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayalon, L. A Typology of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Demographic Correlates and Reasons for Limited Public Engagement in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208740

Ayalon L. A Typology of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Demographic Correlates and Reasons for Limited Public Engagement in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208740

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyalon, Liat. 2024. "A Typology of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Demographic Correlates and Reasons for Limited Public Engagement in Pro-Environmental Behaviors" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208740

APA StyleAyalon, L. (2024). A Typology of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Demographic Correlates and Reasons for Limited Public Engagement in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability, 16(20), 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208740