The Effect of Brand Lovemark on Reusable Cups in Coffee Shops: Machine Use Intention, Willingness to Pay a Deposit, and Green Brand Loyalty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Lovemarks Theory: Brand Love and Brand Respect

2.2. CSR Practices on Consumer Behavioral Outcomes in the Coffee Shop Industry

2.3. Green Brand Loyalty

2.4. Gender Effects on CSR Practices

2.5. Proposed Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Sample

3.2. Procedures and Stimuli

3.3. Measures

4. Result

4.1. The Profile of Participants

4.2. Coffee Shop Visit-Related Characteristics of the Respondents

4.3. Validity and Reliability

4.4. Mean Difference between the Levels of Brand Lovemark (Low vs. High) on Behavioral Outcomes toward CSR Practices

4.5. Mean Difference between Gender (Male vs. Female) on Behavioral Outcomes toward CSR Practices

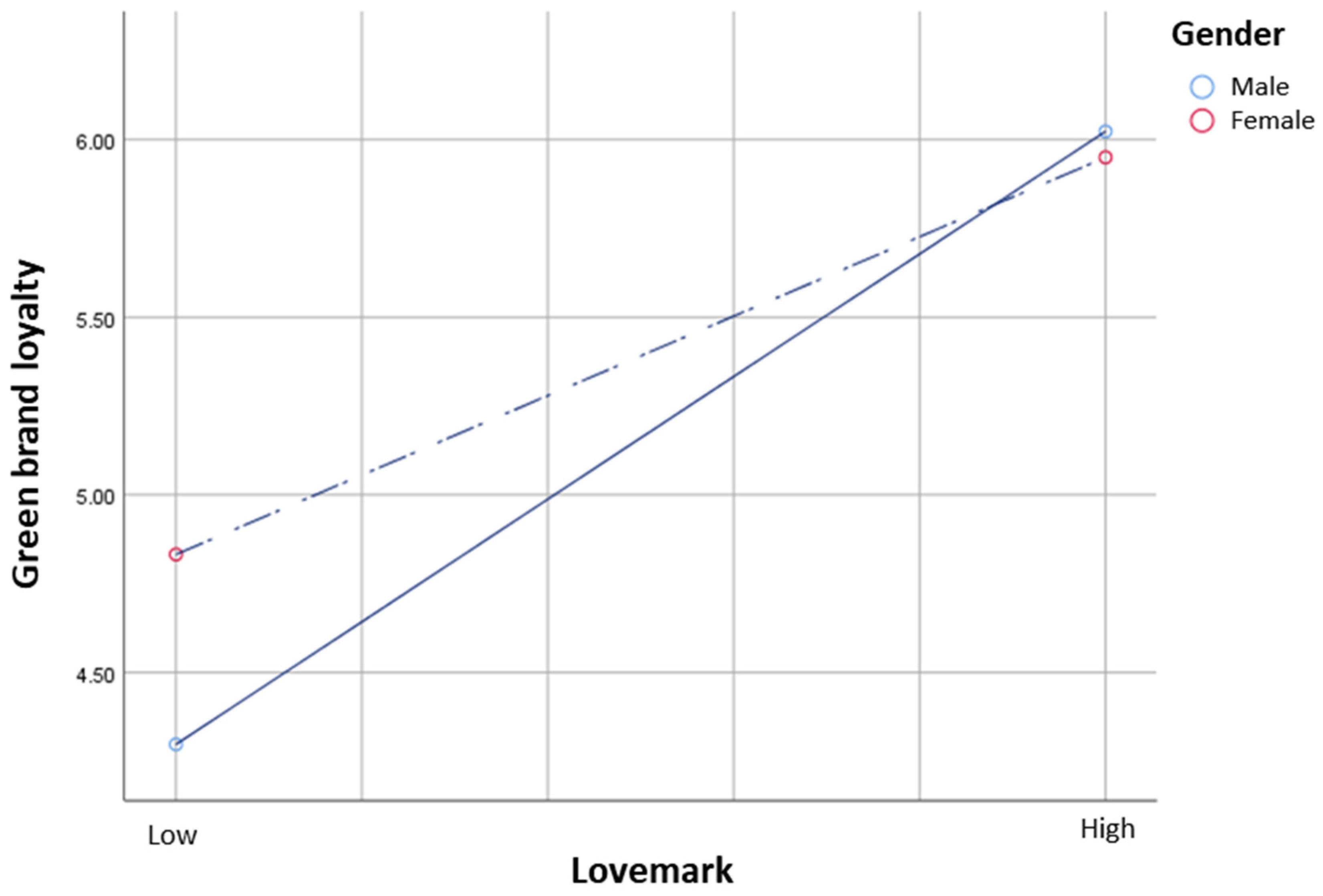

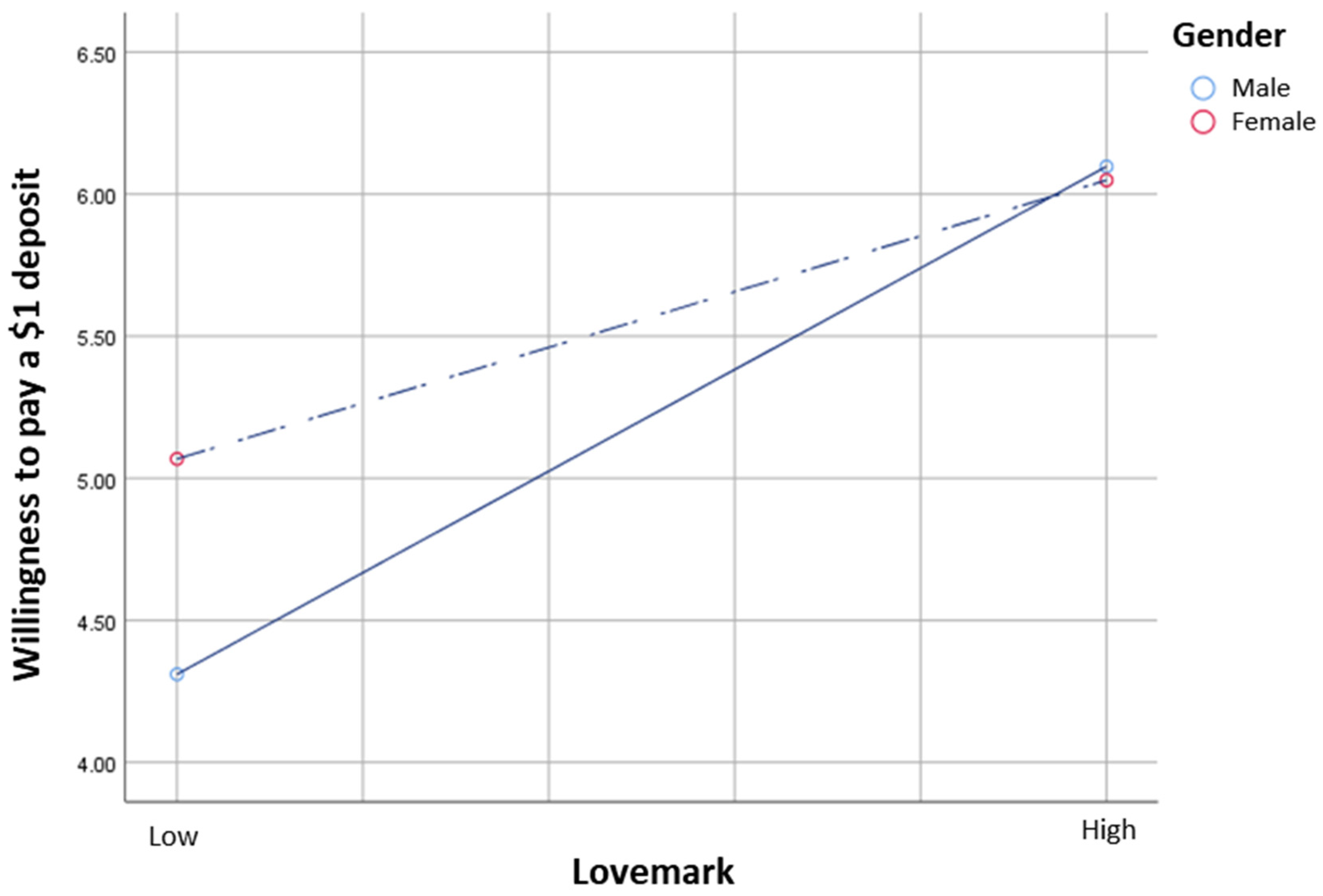

4.6. The Interaction Effect of the Levels of Brand Lovemark and Gender on Behavioral Outcomes

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Wang, G.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M. Effects of hotels’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on green consumer behavior: Investigating the roles of consumer engagement, positive emotions, and altruistic values. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekasari, A. In-store communication of reusable bag: Application of goal-framing theory. J. Manaj. Pemasar. Jasa 2021, 14, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Stadlthanner, K.A.; Andreu, L.; Font, X. Explaining the willingness of consumers to bring their own reusable coffee cups under the condition of monetary incentives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Environmental and Social Impact Report. Available online: https://stories.starbucks.com/uploads/2022/04/Starbucks-2021-Global-Environmental-and-Social-Impact-Report-1.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Ferreira, J.; Ferreira, C. From bean to cup and beyond: Exploring ethical consumption and coffee shops. J. Consum. Ethics 2018, 2, 20834. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, H.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Drivers of brand loyalty in the chain coffee shop industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Davis, E.A.; Weaver, P.A. Eco-friendly attitudes, barriers to participation, and differences in behavior at green hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Nazarian, A.; Foroudi, P.; Seyyed Amiri, N.; Ezatabadipoor, E. How corporate social responsibility contributes to strengthening brand loyalty, hotel positioning and intention to revisit? Curr. Issues. Tour. 2021, 24, 1897–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakhajornboon, P.; Sirichodnisakorn, C. The effect of customer perception of CSR initiative on customer loyalty in the hotel industry. Hum. Arts Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 22, 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices: Which practices are important and effective? Caesars Hosp. Res. Summit 2010, 13. Available online: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/hhrc/2010/june2010/13 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Sui, J.J.; Baloglu, S. The role of emotional commitment in relationship marketing: An empirical investigation of a loyalty model for casinos. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2003, 27, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Jang, J.H. The role of gender differences in the impact of CSR perceptions on corporate marketing outcomes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J.; Reilly, T.M.; Cox, M.Z.; Cole, B.M. Gender makes a difference: Investigating consumer purchasing behavior and attitudes toward corporate social responsibility policies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K. Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands; Powerhouse Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1576872703. [Google Scholar]

- Pawle, J.; Cooper, P. Measuring emotion—Lovemarks, the future beyond brands. J. Advert. Res. 2006, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Market. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amegbe, H.; Dzandu, M.D.; Hanu, C. The role of brand love on bank customers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, R.; Shapoval, V.; Murphy, K.S. Measuring Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of green practices at Starbucks: An IPA analysis. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Parsa, H.G.; Self, J. The dynamics of green restaurant patronage. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.H.; Lin, G.Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, P.Z.; Su, Z.C. Exploring the effect of Starbucks’ green marketing on consumers’ purchase decisions from consumers’ perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyer, E.H. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: Do consumers really care about business ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N. Consumers’ intention to purchase environmentally friendly wines: A segmentation approach. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 13, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazon, M.; Delgado, E. The moderating role of price consciousness on the effectiveness of price discounts and premium promotions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÇavuĢoğlu, S.; Demirağ, B.; Jusuf, E.; Gunardi, A. The effect of attitudes toward green behaviors on green image, green customer satisfaction and green customer loyalty. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 33, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Patino, A.; Kaltcheva, V.D.; Pitta, D.; Sriram, V.; Winsor, R.D. How important are different socially responsible marketing practices? An exploratory study of gender, race, and income differences. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Kim, D.Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility, ability, reputation, and transparency on hotel customer loyalty in the US: A gender-based approach. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeley, E.A.; Gardner, W.L.; Pennington, G.; Gabriel, S. Circle of friends or members of a group? Sex differences in relational and collective attachment to groups. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2003, 6, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.E. Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0126825503. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Lehto, X.; Morrison, A.M. Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V.; Van Osselaer, S.M.; Bijmolt, T.H. Are women more loyal customers than men? Gender differences in loyalty to firms and individual service providers. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Starbucks Creates a Mess and a Hassle as It Tries to Go Green. Available online: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/11/09/business/industry/Starbucks-StarbucksCoffeeKorea-plastic/20211109184029473.html (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Park, J.S.; Ha, S.; Jeong, S.W. Consumer acceptance of self-service technologies in fashion retail stores. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 25, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanis, A.; Athanasopoulou, P. Understanding lovemark brands: Dimensions and effect on Brand loyalty in high-technology products. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2018, 22, 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthanorhan, A.; Awang, Z.; Rashid, N.; Foziah, H.; Ghazali, P. Assessing the effects of service quality on customer satisfaction. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1473756540. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0070474659. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1462534661. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Huan, T.C.T. Renewal or not? Consumer response to a renewed corporate social responsibility strategy: Evidence from the coffee shop industry. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Descriptive | Frequency (n = 263) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 139 | 52.9 |

| Female | 124 | 47.1 | |

| Age | 18–30 | 93 | 35.4 |

| 31–40 | 118 | 44.9 | |

| 41–50 | 33 | 12.5 | |

| 51–60 | 12 | 4.6 | |

| 60 or order | 7 | 2.7 | |

| Highest Education Level | High school or less | 49 | 18.6 |

| Some college | 45 | 17.1 | |

| College | 130 | 49.4 | |

| Graduate School | 69 | 14.8 | |

| Household Income | Less than $20,000 | 19 | 7.2 |

| $20,000 to $39,000 | 52 | 19.8 | |

| $40,000 to $59,999 | 83 | 31.6 | |

| $60,000 to $79,999 | 61 | 23.2 | |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 30 | 11.4 | |

| $100,000 and above | 18 | 6.8 |

| Variables | Descriptive | Frequency (n = 263) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The visit frequency of coffee shop | Everyday | 82 | 31.2 |

| 3~4 a week | 96 | 36.5 | |

| 1~2 a week | 65 | 24.7 | |

| 1~2 a month | 16 | 6.1 | |

| Less than once a month | 4 | 1.5 | |

| The type of the preferred coffee shop | National/regional chain (e.g., Starbucks, Peet’s Ccoffee, Caribou Coffee, The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, Dunkin’, etc.) | 199 | 75.7 |

| Local chain (e.g., Think Coffee, Urth Caffe, Tea Lounge, etc.) | 64 | 24.3 | |

| The main purpose of visiting coffee shops | Relax and enjoy the ambiance | 148 | 56.3 |

| Hang out with people | 40 | 15.2 | |

| Work or Study | 46 | 17.5 | |

| Use free Wi-Fi | 10 | 3.8 | |

| Earn membership benefits (e.g., membership points) | 6 | 2.3 | |

| No other reasons. I only take out coffee | 13 | 4.9 | |

| A primary factor affecting visiting coffee shops | Coffee quality | 192 | 73.0 |

| Atmosphere | 30 | 11.4 | |

| Service | 13 | 4.9 | |

| Green image | 11 | 4.2 | |

| Location | 8 | 3.0 | |

| Price | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Others | 3 | 1.1 |

| Dimensions/Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lovemark | 0.886 | 0.979 | |

| I love Starbucks. | 0.630 | ||

| Starbucks is a joy to me. | 0.835 | ||

| Starbucks is really awesome. | 0.843 | ||

| I respect Starbucks. | 0.704 | ||

| I am hooked on Starbucks. | 0.796 | ||

| Starbucks leads the development of coffee shops. | 0.655 | ||

| Green brand loyalty | 0.906 | 0.974 | |

| I would recommend this coffee shop to my friends or others because it is environmentally friendly. | 0.601 | ||

| I would like to come back to this coffee shop in the near future because it is environmentally friendly. | 0.815 | ||

| This coffee shop would be my first choice over other coffee shops because it is environmentally friendly. | 0.797 | ||

| I will say positive things about this coffee shop because it implements an environmentally friendly policy. | 0.769 | ||

| Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | 0.891 | 0.961 | |

| I would be prepared to pay a deposit ($1) to be able to use Starbucks again. | 0.808 | ||

| I would be a customer of Starbucks even if it received the deposit ($1) for its coffee cups, as long as it was reasonable. | 0.756 | ||

| I would accept the policy of paying a deposit ($1) because Starbucks matches my expectations. | 0.655 | ||

| Machine use intention | 0.903 | 0.974 | |

| I would like to use the return machine at Starbucks. | 0.641 | ||

| It would be a pleasure for me to use the return machine at Starbucks. | 0.857 | ||

| It would be desirable for me to learn how to use the return machine at Starbucks. | 0.795 | ||

| Assuming that I have access to this return machine at Starbucks, I intend to use it. | 0.810 |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Cronbach’s α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lovemark | 5.49 | 1.04 | 0.884 | 0.941 | |||

| 2. Green brand loyalty | 5.50 | 1.00 | 0.826 | 0.820 ** | 0.952 | ||

| 3. Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | 5.60 | 1.05 | 0.787 | 0.756 ** | 0.852 ** | 0.944 | |

| 4. Machine use intention | 5.44 | 1.09 | 0.854 | 0.767 ** | 0.863 ** | 0.814 ** | 0.950 |

| Dependent Variable | The Level of Brand Lovemark | Mean | N | S.D. | t | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green brand loyalty | Low | 4.58 | 92 | 1.05 | −12.192 | 0.000 *** |

| High | 5.99 | 171 | 0.50 | |||

| Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | Low | 4.71 | 92 | 1.19 | −10.444 | 0.000 *** |

| High | 6.08 | 171 | 0.54 | |||

| Machine use intention | Low | 4.51 | 92 | 1.18 | −10.940 | 0.000 *** |

| High | 5.94 | 171 | 0.60 |

| Dependent Variables | Gender | Mean | N | S.D. | t | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green brand loyalty | Male | 5.49 | 139 | 1.13 | −0.155 | 0.042 ** |

| Female | 5.51 | 124 | 0.82 | |||

| Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | Male | 5.54 | 139 | 1.23 | −0.922 | 0.001 *** |

| Female | 5.66 | 124 | 0.79 | |||

| Machine use intention | Male | 5.43 | 139 | 1.19 | −0.034 | 0.005 ** |

| Female | 5.44 | 124 | 0.95 |

| Green Brand Loyalty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | p | F | R2 | Δ R2 | Δ F | |

| (Constant) | 4.297 | 0.110 | 38.993 | 0.000 | 80.232 *** | 0.482 | 0.021 | 10.523 ** |

| Lovemark | 1.727 | 0.133 | 13.025 | 0.000 | ||||

| Gender | 0.535 | 0.151 | 3.544 | 0.000 | ||||

| Lovemark × Gender | −0.609 | 0.188 | −3.244 | 0.001 | ||||

| Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | ||||||||

| β | SE | t | p | F | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

| (Constant) | 4.310 | 0.122 | 35.399 | 0.000 | 64.975 *** | 0.429 | 0.033 | 15.127 *** |

| Lovemark | 1.787 | 0.147 | 12.198 | 0.000 | ||||

| Gender | 0.758 | 0.167 | 4.543 | 0.000 | ||||

| Lovemark × Gender | −0.806 | 0.207 | −3.889 | 0.000 | ||||

| Machine use intention | ||||||||

| β | SE | t | p | F | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

| (Constant) | 4.128 | 0.125 | 33.043 | 0.000 | 67.474 *** | 0.439 | 0.039 | 18.065 *** |

| Lovemark | 1.896 | 0.150 | 12.610 | 0.000 | ||||

| Gender | 0.714 | 0.171 | 4.171 | 0.000 | ||||

| Lovemark × Gender | −0.904 | 0.213 | −4.250 | 0.000 | ||||

| Green Brand Loyalty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | t | 95% CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| Male | 1.727 | 0.133 | 13.025 *** | 1.466 | 1.988 |

| Female | 1.118 | 0.133 | 8.426 *** | 0.857 | 1.380 |

| Willingness to pay a $1 deposit | |||||

| Effect | SE | t | 95% CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| Male | 1.787 | 0.147 | 12.198 *** | 1.499 | 2.076 |

| Female | 0.981 | 0.147 | 6.688 *** | 0.692 | 1.270 |

| Machine use intention | |||||

| Effect | SE | t | 95% CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| Male | 1.896 | 0.150 | 12.610 *** | 1.600 | 2.192 |

| Female | 0.991 | 0.150 | 6.589 *** | 0.695 | 1.288 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noh, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, D.-Y. The Effect of Brand Lovemark on Reusable Cups in Coffee Shops: Machine Use Intention, Willingness to Pay a Deposit, and Green Brand Loyalty. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031113

Noh Y, Kim MJ, Kim D-Y. The Effect of Brand Lovemark on Reusable Cups in Coffee Shops: Machine Use Intention, Willingness to Pay a Deposit, and Green Brand Loyalty. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031113

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoh, Yooin, Min Jung Kim, and Dae-Young Kim. 2024. "The Effect of Brand Lovemark on Reusable Cups in Coffee Shops: Machine Use Intention, Willingness to Pay a Deposit, and Green Brand Loyalty" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031113

APA StyleNoh, Y., Kim, M. J., & Kim, D.-Y. (2024). The Effect of Brand Lovemark on Reusable Cups in Coffee Shops: Machine Use Intention, Willingness to Pay a Deposit, and Green Brand Loyalty. Sustainability, 16(3), 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031113