Abstract

Urban parks play a crucial role in enhancing the social interactions of older adults. However, despite the broad recognition of urban parks’ benefits, there is a notable gap in research focusing on their role in promoting social interactions, particularly in Asia. This study explores the effects of personal, social, and physical factors and park use patterns on older adults’ social interactions. Survey data from 589 older adults aged 50 years or older were collected through face-to-face and online questionnaires and were analyzed using a hierarchical multiple regression model. The results showed that personal factors, social factors, physical factors, and park use patterns explained 10.8%, 8.2%, 9.4%, and 2.3% of the total variance in park social interactions, respectively. Key factors like gender, health status, social cohesion, features, conditions, accessibility, and park use patterns were found to significantly influence these interactions. This study provides empirical evidence to support the important role of urban parks in facilitating social interactions among older adults and contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex factors affecting these interactions. To meet the needs of older adults and maximize the social health benefits, these prominent factors should be emphasized in policy development and interventions, integrating older adults’ perceptions and personal experiences.

1. Introduction

Global aging represents a significant demographic trend of the 21st century. According to a National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) report, in 2022, approximately 38% of China’s total population was 50 years old or above. Moreover, a report titled “China’s Demographic Outlook to 2040 and Its Implications Projections” states that from 2015 to 2040, China’s population aged 50 and over will increase by about 2.5 billion [1]. This indicates an exceptionally rapid rate of aging in China’s population. The aging population profoundly impacts various aspects of society, economy, and environment, posing new challenges and requirements for urban planning, construction, and management. In response, China has formulated a national five-year plan aligned with the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, aiming to enhance the health and well-being of its aging population and urgently address the need for age-friendly cities and communities. This is a challenge not only for China but one that many other countries around the world are facing. Creating age-friendly urban environments that cater to the diverse needs of older adults and enhance their quality of life remains a pressing global issue [2]. Proactive measures are essential for sustainability, particularly social sustainability, to ensure the health, well-being, and environmental quality of current and future generations. Establishing supportive and inclusive environments for older adults is key to this goal and a cornerstone of sustainable city development.

Urban parks provide residents with places for leisure, recreation, sports, and social interaction, while also serving ecological functions such as regulating the urban climate, purifying urban air, and protecting urban biodiversity [3]. Abundant evidence indicates that urban parks are important for improving the quality of life of residents as they can provide strong health benefits, social benefits, and environmental benefits [4]. Urban parks have benefits for all age groups, but they may be of more special significance for older adults. Their needs and use of urban parks may differ from other age groups [5].

A growing challenge for older adults, especially those in one-child families, is social isolation. Older adults entering or approaching retirement, upon leaving the workplace, and as their children gain independence lose crucial spaces for interpersonal and social networking [6]. Simultaneously, these individuals face an increased risk of losing partners and friends, a risk that is higher than in younger populations [7]. This physical and psychological fear is extremely challenging for them, and the lack of social connections can lead to serious health outcomes [8,9]. The prevalence of social isolation due to a lack of social integration ranges from 7 to 17% [10]; meanwhile, approximately 40% of older adults report experiencing loneliness [11].

According to the 2018 White Paper on the Mental Health of the Elderly in China, 63% of Chinese seniors frequently experience loneliness. The white paper further reveals that over 25% of Chinese older adults above 60 years of age have contemplated suicide due to physical or other varied reasons [12]. These statistics underscore the seriousness and widespread nature of mental health issues among Chinese older adults. Loneliness, often resulting from life events like retirement, widowhood, financial challenges, and interpersonal issues, is the primary cause of psychological problems among older adults, which in turn is associated with a variety of health problems or risks [13]. Face-to-face social interactions can be effective for older adults in reducing loneliness due to life changes. However, social networks tend to shrink with age, as changes in living situations and physical functioning make it difficult to maintain social ties [14,15], and widespread ageism further limits their opportunities for social interaction [16].

Quality urban park design that meets older adults’ needs for social interaction not only boosts their quality of life but also contributes to social sustainability. Such design encourages older adults’ social interaction, reduces loneliness and isolation, and has a favorable impact on societal health and well-being. However, urban parks are underutilized for the benefit of various groups [17], a situation that deprives older adults of opportunities for social interaction.

Urban parks, despite being among the most extensively studied green spaces, are typically linked more with physical activity than social interaction. Numerous sociologists and urban designers have examined the social roles of public spaces over time, contending that successful public spaces possess subjective qualities like supportiveness, fulfillment, and discovery [18]. Such qualities cater to fundamental needs, encompassing both passive and active participation. Moreover, frequent face-to-face contact helps to build social bonds [19]. However, the issue arises as social cohesion diminishes, leading to a widespread deficit in social interaction among residents. Despite ongoing enhancements in park quality, this trend continues, with older adults potentially being the most socially isolated group relative to other age groups [20].

While urban parks are known to facilitate social interactions among older adults, limited research has been conducted on how the urban park environment contributes to these interactions [21]. Existing empirical studies primarily focus on qualitative interviews and observations of older adults’ social interactions, often overlooking the quantitative assessment of the social and physical environment’s role. Furthermore, the unique characteristics of this age group imply that findings from certain settings and subgroups may not be applicable to others. For instance, shaded seating areas have been shown to facilitate social interactions, as evidenced by studies conducted in Kuala Lumpur [22], Guangzhou [23], and Hong Kong [24]. Conversely, a study from Finland demonstrates a preference for sunlight over shade, attributed to the cooler summer temperatures prevalent in the region [25]. This preference is clearly influenced by geographic climate factors. Similarly, different types of facilities and amenities may encourage specific behaviors in various populations [26]. Consequently, questions remain about how older adults utilize urban parks and which park features support their social interactions.

2. Literature Review

Socio-ecological models support the importance of considering multiple layers of determinants of health behaviors (i.e., social interactions in this study), which include a range of direct or indirect factors, such as personal, social, and physical factors. This is important for this study because they attempt to capture the multiple layers of factors that may influence social interactions, allowing researchers to focus on at least one layer while recognizing confounding or interacting influences at other layers. To fill some of the knowledge gaps mentioned above, this study first explored the relationship between urban parks and social interactions and previous measures. Then, based on the theoretical framework, it examined the role of specific social and physical environments as well as personal factors in the social interactions of older adults.

2.1. Urban Park and Social Interaction

Urban parks, as a vital component of public open spaces, not only provide residents with opportunities for social interaction, physical activity, relaxation, and access to nature but are also important places for organized and informal activities [27], enhancing social well-being and the physical and mental health of residents [28]. Urban parks play an important role in offering social outlets and facilitating connections among individuals who might not typically interact [29]. As a result, most social activities and social interactions take place in public open spaces such as urban parks.

Social interaction is any contact between people, both verbal and nonverbal, resulting in a social experience, which encompasses all types of activities [30]. Interaction takes place when individuals gather with a specific purpose, and even eye contact or physical gestures when entering or exiting others’ view [31], which highlights the significance of public spaces like urban parks. Some scholars have noted that urban park environments attract, trigger, and reinforce interactional behaviors, and that such social connections may be a potential mechanism for the relationship between green spaces and health [32]. Furthermore, fostering social interactions in such environments is a cost-effective strategy to enhance health and encourage active aging [33].

While interactions in public open spaces are seen by some as overly informal and random, others acknowledge their positive social impacts. This is because urban parks provide opportunities for social interactions between people of different social backgrounds, ethnic backgrounds, and age groups [34]. Providing social interactions through potential spaces can be weakly occurring and one-time interactions or even long-term more structured interactions [35]. These interactions can mitigate daily life stresses and reduce community tensions [36]. Engaging in meaningful social activities, particularly in high-quality urban parks with moderate activity, can improve the physical, mental, and social well-being of older adults.

Existing research on social interaction predominantly assesses objective aspects of social interaction, including frequency of neighborhood interactions [37,38], number of social contacts [39], type of contact [40], and social network size [41]. Additionally, subjective aspects like satisfaction [42] and needs [43] have been examined. While these studies mainly focus on neighborhood interactions, there is limited knowledge about older adults’ social interactions in urban public spaces. In the context of landscape planning, few studies explore the social interactions of older adults in urban parks. For instance, Moulay et al. assessed park users’ intensity of social interaction, park contact, and interaction types via observation and questionnaire [17]. Salih et al. investigated the frequency of social activities in pocket parks using questionnaires [44]. Overall, the number of social interactions is a key indicator in evaluating older adults’ social interactions, reflecting how active older adults are in their social interactions. Some scholars note that the frequency of social interactions reflects satisfaction with these interactions and argue that, generally, increased social interactions can reduce feelings of loneliness [45]. Research indicates that 2–3 daily face-to-face social interactions can enhance mood and reduce loneliness in older adults [46], while some scholars note that increased social interaction is not necessarily beneficial, as it may not always yield positive exchanges [47]. However, regardless of the quality of socialization, it is more likely for older adults to feel positive emotions when they feel noticed and understood.

While Oldenburg asserts that only verbal social interactions are effective [48], recent studies indicate that nonverbal interactions also enhance physical and mental health [49]. This form of social interaction is important for older adults to socialize because they can feel engaged in urban parks. Therefore, this study evaluates older adults’ social interactions in parks by measuring the frequency of both verbal and nonverbal face-to-face interactions.

2.2. Factors Affecting Social Interaction in Parks

2.2.1. Physical Factors

Many studies have recognized that social interactions are influenced by the physical characteristics of urban public spaces. For instance, comfortable and appealing open spaces are likely to attract visitors, subsequently creating opportunities for social interaction [50]. A survey of nine parks in Mexico revealed that factors such as distance, tree abundance, safety, cleanliness, and playground quality influence users’ patterns of use, with improvements in these attributes enhancing social interaction among users [51]. An exploration of factors influencing residents’ social interactions in Australia found a positive correlation between the frequency of park use, satisfaction with resting spaces, and environmental connectivity [52]. Water features in landscapes are known to offer relaxation and stress relief to older adults, thus encouraging their visits [53]. Veitch et al. [54] identified parks as a place to promote social interactions beneficial to older adults’ health, identifying the most important park features through an online survey and joint analysis, including calm and relaxing environments, specifically shady trees, and relaxing walking paths were prioritized to encourage older adults’ visitation and social interactions. A systematic review highlighted that enhancing residents’ perception of urban green spaces boosts their usage, thereby increasing social interaction opportunities. Despite inconsistencies in the findings of some studies regarding physical characteristics, amenities, maintenance, safety, accessibility, aesthetics, and usage patterns consistently have a significant impact on social health [55]. This perspective was reinforced by a recent review, affirming that physical features, perceptions, and usage of green spaces directly influence social interactions, with factors like perceived greenness, proximity, and safety being more indicative than objective environmental measures [56].

2.2.2. Social Factors

The social environment, a complex notion, encompasses the “immediate physical surroundings, social relationships, and cultural contexts” within a specific area [57]. This indicates the need to consider both social and physical environments in the study of social interactions. Yet, according to the literature review, there is a limited number of studies that specifically explore the role of the social environment in parks in enhancing social interactions.

From the subjective perspective of the social environment, several studies have investigated the influence of different factors on park use and social interactions. For instance, Broyles et al. conducted surveys on social capital perceptions at 27 neighborhood parks in Los Angeles, examining trust, reciprocity norms, and common interests [58]. They found that parks with higher social capital levels experienced greater use. Otero Pena et al. analyzed individual-level park usage, with self-reported data revealing positive effects of social cohesion and trust on park usage, as well as significant correlations with parks’ physical attributes [59]. A study examining the relationship between neighborhood green spaces, social environments, and mental health in four European cities found mixed results: the correlation between green spaces and mental health varied, showing both significant and non-significant links across cities, whereas social contact consistently correlated with mental health in all four cities [60]. Meanwhile, another study explored the intergenerational and peer interactions of older adults in terms of personal, social, and physical aspects, where the social aspects investigated subjective community services, social cohesion, and perceived trust, as well as objective neighborhood age composition, and environmental attributes related to the social and physical environments were found to be key predictors [61]. Other literature reviews on the social context of park use express somewhat different views. A review integrating 21 qualitative studies found that there appeared to be reciprocal positive or negative effects between the social and physical environments, emphasizing that for women and adolescents, a safe and supportive social environment is essential for social interaction, regardless of the physical environment’s condition [62]. One study, synthesizing data from 12 studies, suggests that the combined influence of the social and physical environments enhances community engagement among older adults [63].

2.2.3. Personal Factors

The literature on social interactions indicates that personal characteristics such as gender, age, and income predict social interactions. Collectively, studies on personal characteristics have shown varied results depending on location, spatial context, and subpopulation groups. For instance, one study indicated that men frequent community green spaces more than women in deprived areas [64]. Conversely, a study on the built environment’s impact on older adults’ leisure and physical activity in Nanjing found no gender-based differences in engagement levels [65]. Conflicting findings exist regarding park usage and income disparities. For instance, one study indicates that lower-income households do not utilize green spaces as actively [4,66]. Another study highlights that low-income residents have a greater need for public green space activities than wealthier residents [67]. A study investigated in China suggests that higher social capital and social trust can mitigate the decline in the well-being of older adults caused by income disparity [68]. Although numerous studies have explored how personal characteristics affect green space use, fewer have focused on older adults’ use of parks for social interaction, a notable gap given their increased risk of social isolation. Instead, a study of 34 cities around the world found that socioeconomic characteristics and their surroundings may influence health outcomes, not just the green space itself [69].

2.2.4. Summary

In summary, over the past few decades, researchers concerned with public health, urban planning, and design have been trying to understand the factors that influence the relationship between health behaviors (this paper focuses on social interactions) and urban green spaces. The World Health Organization (WHO) posits that healthy aging can be fostered through an ecological approach, which influences health via the interaction of individual capabilities, home environment, community, and the broader sociocultural environment. Recently, numerous scholars have concentrated on various ecological models of aging, recognizing this approach as increasingly effective in promoting long-term health among older adults. However, few studies have investigated the impact of these factors on the use of urban parks by older adults for social interactions. This research only found a few studies examining the association between the environment and social interactions in older adults through quantitative methods. Nevertheless, these studies insufficiently considered the potential influence of a combination of personal, social, and physical environmental factors. Additionally, previous studies have yielded inconclusive results, potentially influenced by various factors such as geographic location, environment type, and user demographics. Therefore, there is a need for further investigations to clarify which factors influence the social interactions of older adults.

It is worth noting that the impact of park use patterns (e.g., frequency, duration, etc.) on social interactions has been proposed in many studies. Huang & Lin found that different types of urban green spaces were significantly correlated with individuals’ social health (including social connectedness, social relationships, social support, and social contact) through a review of 60 articles and noted that park use had a direct impact on social health and was influenced by both urban green space and respondents’ personal characteristics [58]. Similarly, a recent literature review analyzing 53 studies on the correlation between green spaces and social interaction also noted that the perceived physical environment has the potential to indirectly influence social interaction through patterns of use [56].

Thus, guided by these conceptual frameworks and empirical evidence, our study investigated three main factors influencing older adults’ social interactions through a questionnaire, including personal characteristics, the social environment, and the physical environment, with the addition of an investigation of park use patterns. Personal characteristics comprised gender, age, retirement status, income, and health status. The social environment involved subjective assessments of social cohesion, social support, and sense of belonging. The physical environment entailed subjective evaluations of the features, conditions, aesthetics, safety, and accessibility of urban parks. Patterns of use encompassed both the frequency and duration of usage. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between these variables and the social interactions of older adults in the context of urban parks.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Context

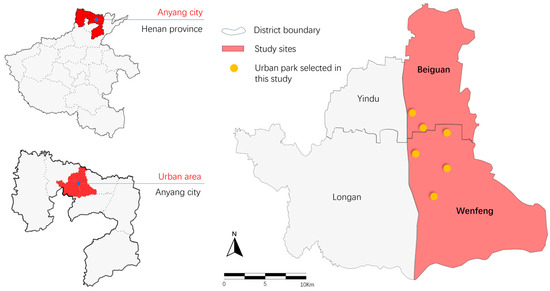

This study was conducted in Anyang city, Henan province, China. Anyang encompasses a land area of 7413 km2 and has a population of approximately 5.41 million, located in the central region of China. As a typical medium-sized city, it boasts an urbanization rate of 54.69%, aligning with the national average, as reported in the 2021 China Census. The city’s resident population includes 1.85 million individuals aged 50 and above, constituting 34.14% of the total population [70]. Compared to the sixth national census in 2010, there has been an increase of 4.95 percentage points in the proportion of those aged 50 and above, indicative of the ongoing aging of the population in Anyang. The urban area includes four administrative districts, namely Wenfeng District, Beiguan District, Longan District, and Yindu District. Wenfeng and Beiguan Districts, having the highest residential densities, were chosen as our study sites.

According to the Standard for the Classification of China’s Urban Parks (CJJ/T85-2017) [71], comprehensive urban parks are public parks that are larger and provide abundant space for a variety of recreational activities. In alignment with this study’s objectives, the selected urban parks shared these characteristics: (a) free and open public access; (b) extensive green space and numerous facilities; (c) convenient accessibility; and (d) popularity within the city’s urban areas. Six urban parks from two districts were selected for data collection, as shown in Figure 1. The selection was proportionate to the population in each district [72], leading to the choice of two parks in Beiguan District and four parks in Wenfeng District. In Beiguan District, Huanshui Park and Renmin Park were selected, while Wenfeng District included Yi Park, Shangwu Park, Sanjiaohu Park, and Honghe Park. Each park, situated near residential areas, boasts considerable green spaces and public facilities. Free access to these parks makes them vital locales for outdoor activities, particularly for older adults in surrounding neighborhoods.

Figure 1.

Location of this study.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted from June to September 2023. A mixed-method approach for questionnaire collection was employed, encompassing both on-site distribution and online collection. Prior to formal data collection, a face-to-face pretest was conducted, involving a random survey with a total of 12 respondents. The pretest primarily evaluated the questionnaire’s wording, format, and implementation process. Respondents in the pretest reported no difficulties or ambiguities in the questions. All respondents were required to read or have the informed consent form explained by the investigator, and to sign the consent form before completing the questionnaire. The eligibility criteria for the participants were as follows: (a) including older adults aged 50 years and above, in accordance with the sociologically significant criterion of old age, namely retirement age [73]; (b) excluding older adults requiring long-term care or assisted living; and (c) including older adults who were literate and capable of understanding and responding to the questions.

In this study, a total of 637 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in the collection of 589 valid responses, comprising 213 from field surveys and 376 via the Internet. During the field survey in the park, questionnaires were randomly distributed to older adults, and in cases of refusal, the search for a new respondent continued. The web-based questionnaire was disseminated using two methods: firstly, by setting up a link in the field and encouraging participating older adults to share it with their friends, family, or social networks; secondly, by distributing it via social media groups (WeChat) to older adults in residential areas near the park, employing a snowball sampling technique. During the on-site survey, respondents who were willing but lacked the time to complete the questionnaire in the park were provided with the link to complete it at their convenience. Data collection occurred on weekdays and weekends with favorable weather and was suspended during inclement weather, such as rain.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Social Interaction

In this study, social interactions were assessed primarily in terms of the number of social interactions older adults had in urban parks. The frequency of social interactions was used as a measure to determine their number. The frequency of social interactions was assessed using items adapted from a modified version of the Veitch et al. [54], Moulay & Ujang [74], and Lubben Social Networking Scale [75]. This included four items, including face-to-face verbal and nonverbal social interactions, (e.g., interactions with someone known). Responses were measured on a five-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = mostly, 5 = always). Cronbach’s alpha of the construct was 0.878.

3.3.2. Physical, Social, and Personal Factors

Physical Factors. Respondents assessed their subjective perceptions of the physical characteristics of urban parks. Park characteristics were measured with reference to a framework developed by Bedimo-Rung et al. [4], and specific measurement items were based on this framework and other studies in the context of urban parks [76,77,78], as well as studies in the context of urban parks in China [79,80,81]. Factor analysis was conducted on the initial 32 items, resulting in the deletion of 2 items (parks with wildlife and parks with separate walking and running paths), as their meanings substantially diverged from the intended components. Reanalysis of the remaining 30 items through principal component analysis yielded five factors, accounting for a cumulative variance contribution of 65.77%. The KMO was 0.931, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001). These factors were identified as features, condition, aesthetics, safety, and accessibility (Table 1). Cronbach’s alpha of the construct was 0.914.

Table 1.

Factor analysis of physical factors.

Social Factors. Social factors investigated perceived social cohesion, social support, and sense of belonging. Social cohesion items refer to the Social Cohesion and Trust Scale [82]. The items for social support are mainly based on the Social Support List 12-Interaction (SSL12-I) [83]. The measure of belonging was primarily based on a scale developed by Mowe et al. [84], which assesses an individual’s sense of welcome and belonging in a park setting. This scale was further refined through modifications in several subsequent studies [85]. Each of the three dimensions contains 5 items and were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Following the factor analysis, three common factors with initial eigenvalues greater than one were established, collectively accounting for 65.14% of the variance in the original variables. The analysis yielded a KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) value of 0.909 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001). These factors were identified as social cohesion, social support, and sense of belonging (Table 2). Cronbach’s alpha of the construct was 0.883.

Table 2.

Factor analysis of social factors.

Personal Factors. Personal factors were identified through a literature review, focusing on personal and socio-demographic characteristics, including gender, age, retirement status, income, and health status.

3.3.3. Park Use

Park use was defined in terms of frequency, duration, and regularity, with measurement items adapted from a validated and reliable park use questionnaire [86]. The survey comprised four items (e.g., how often do you usually visit the park? How long do you usually spend at the park?). Cronbach’s alpha of the construct was 0.854.

3.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis of this study was conducted using SPSS version 27.0. Descriptive statistics were examined, and the normality of the data distribution for each variable was assessed using skewness and kurtosis values. All predictor variables exhibited values within the ±3 range [87], indicating consistency with a normal distribution. Multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values. All predictor variables were within acceptable thresholds, with tolerance levels greater than 0.30 and VIF ratios less than 4.0 [88], suggesting no significant covariance issues among the independent variables.

The relationship between the variables was tested by first testing the Pearson correlation analysis of the variables, and then by further constructing the hierarchical linear regression analysis model to study the mutual influence relationship between the independent variables on the dependent variables. Independent variables in this study were classified into four categories: personal factors, social factors, physical factors, and park use patterns. Hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted by introducing the models sequentially in the order mentioned.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Among the 589 respondents, 54.2% were female and 45.8% were male. Many of the respondents were aged between 50 and 60 years (83.6%), with only 5.4% of respondents aged 65 and over. Most of the respondents had attained high school education or higher (84.2%). A total of 73% of the respondents were retired, and among the pre-retirement occupations or current occupations, there were more employees in enterprises, accounting for 47.5%, followed by employees in organizations and institutions, accounting for 30.1%. Income (CNY/month) was concentrated at the 1500–3000 level (54.7%), followed by 3000–4500 at 21.1%. The self-reported health status indicated that most of the respondents were in overall good health, with 40.7% reporting relatively good health, 36.3% fair health, and 12.7% very good health. Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics of this study sample.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics (n = 589).

4.2. Correlations between Variables

Table 4 summarizes the correlations between the variables of this study. The results of the correlation between the frequency of social interaction and social factors show that social cohesion (r = 0.334, p < 0.01), social support (r = 0.214, p < 0.01), and sense of belonging (r = 0.119, p < 0.01) are all significantly and positively correlated to the dependent variable, and in the physical factors’ correlation results, features (r = 0.382, p < 0.01), conditions (r = 0.312, p < 0.01), aesthetics (r = 0.2, p < 0.01), safety (r = 0.193, p < 0.01), and accessibility (r = 0.245, p < 0.01) all had significant positive correlations with the dependent variable. Furthermore, use pattern (r = 0.287, p < 0.01) was also significantly positively correlated with the frequency of social interaction. These factors identified as significantly correlated were included as independent variables in further hierarchical linear regression analyses.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis.

4.3. Hierarchical Linear Regression Model

Table 5 shows the results of the hierarchical linear regression. In model 1, personal factor variables accounted for 10.8% of the variance, with gender and health status (p < 0.01) significantly influencing older adults’ social interactions in urban parks. Model 2 showed that social factor variables contributed 7.9% to the variance, with perceived social cohesion and social support demonstrating statistical significance (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05). With the inclusion of physical factors, features, conditioning, and accessibility being significant (p < 0.001, p < 0.01, and p < 0.01), the predictive power of model 3 further improved by 8.9%, accounting for a combined total of 27.6% of the variance in social interaction. All the independent variables in model 4 collectively explained 29.8% of the variance, with park use patterns contributing 2.2% of the variance compared to model 3. Across the model, gender, health status, social cohesion, features, condition, accessibility, and park use patterns consistently showed significant correlations with older adults’ social interactions in urban parks. Social support dropped out as a significant variable in the full model.

Table 5.

Hierarchical linear regression model.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effects of Personal, Social, Physical, and Park Use Factors on the Social Interaction of Older Adults in Urban Parks

Among the personal factors, gender and health status significantly affected the social interactions of older adults in urban parks, and the personal factors contributed the most to the explanation of social interactions. The model results indicate that older women exert a greater influence on social interactions than older men, and better health status in older adults correlates with a stronger positive impact on social interactions. These results are consistent with previous studies. The results of many studies suggest that compared to men, women are more inclined to engage in social interactions, especially after retirement, and they may have a more active need for social networks to maintain social connections [89]. In addition, older women are also more likely to be inclined to participate in group activities or community-organized events [90], a phenomenon that is more common in public spaces such as urban parks. Self-rated health status-based evidence suggests that good health facilitates older adults’ interactions in parks, possibly because older adults in good health have fewer physical limitations, making it easier for them to socialize with others. Furthermore, good health may also be associated with more positive attitudes toward life and socialization.

This study examined perceived social environment factors and found that social cohesion was significantly and positively correlated with social interactions. Social cohesion is a composite indicator of trust, mutual help, and rapport. Weijs-Perrée et al. found that social cohesion positively influences social interaction [45]. Winsor et al. also noted that it can increase comfort and support among older adults, thus promoting greater social participation [91]. Consequently, older adults perceiving fellow park users as trustworthy can lessen psychological barriers to socialization. Furthermore, a supportive atmosphere in parks might increase older adults’ propensity to engage in social activities. This could lead to more proactive behavior in seeking or offering assistance, enhancing social connections. Most of the older adults in this study are young retired older adults who are affected by social role changes and prone to negative emotions when they are alone for a long period of time, so they are in urgent need of mental comfort in the community environment. A harmonious park environment likely contributes to older adults feeling more accepted and respected, thus encouraging active participation in social interactions and fostering a sense of presence and vitality on a deeper, spiritual level.

This study analyzed older adults’ subjective perceptions of park features, partially reflecting their views. Among these five features (Table 3), condition received the highest rating, followed by features, accessibility, and aesthetics, with safety scoring the lowest. The findings indicate that features significantly influence older adults’ social interactions. Notably, features like seating, fitness equipment, restrooms, vegetation, and shaded areas were crucial to older adults and markedly affected their social interactions. In line with existing research, extensive studies in the literature underscore the profound effect of vegetation on diverse social processes [92,93,94]. Trees and grassy spaces are believed to foster increased participation, thereby enhancing the likelihood of informal social interactions [95]. Additionally, parks should offer essential amenities, including adequate shade, exercise equipment, seating, and restrooms, to encourage older adults’ active engagement in social interactions [21].

Good conditions have potential implications for supporting social interactions. Some studies point to poorly maintained paths as a major barrier to park use for older adults [96,97]. The absence of noise and uncivilized behavior positively affect older adults’ social interactions, and noise such as road traffic has been reported to have less of an impact on people when surrounded by greenery [98,99]. Contrary to visitors who find sounds like children playing, square dancing, and musical instruments disruptive, older adults in this study did not perceive these as noise. A possible explanation for this is that activities such as square dancing and instrumental performances are an important part of older adults’ activities in parks and often bring with them a strong sense of participation. In contrast, the playing and shouting of children may evoke memories of their own children or their grandchildren, resulting in a positive emotional response. Furthermore, older adults may view children’s play and musical activities as social environments that offer opportunities for interaction and observation. While some older adults might initially dislike this “noise,” regular exposure can lead to acclimatization, reducing its perception as a distraction. Therefore, this phenomenon likely results from a mix of cultural background, social needs, and adaptability, reflecting older adults’ unique context.

Similarity, the subjective dimension of urban park accessibility plays a key role in influencing park use and health-related behaviors and significantly affects the correlation between green space and social relationships [100]. In this study, participants were predominantly young retirees. While distance to external spaces was a factor in park choice, accessibility within the park was more critical. If a park is popular and provides numerous leisure activities, people might underestimate the importance of distance; conversely, the impact of distance can be exaggerated [101]. For younger retirees seeking social interaction, accessibility within the park means easier access and participation in social activities. Specifically, enhancements to the road connection network improve access to diverse park areas, thereby increasing mobility and accessibility. These enhancements enable retirees to easily access various park areas and participate in activities, thus expanding opportunities for social engagement and the observation of others.

In the Chinese context, this study did not include urban public safety and security as investigation items, focusing instead on environmental safety aspects like lighting, facilities, and roads. Contrary to studies that emphasize the significant impact of safety, this research found no notable effect of safety on the social interactions of older adults. Two potential reasons for this finding are identified: firstly, the lack of lighting facilities for a long period of time may have lowered the expectations of older adults, and secondly, older adults do not use parks frequently at night; their main activities at night are based on fitness and walking rather than social interactions. However, from the point of the evaluation of the safety aspect, it is necessary to improve the quality of parks. Enhancements are needed in night-time lighting in areas frequented by older adults, better enforcement against motorized vehicles in parks, and attention to the paving’s smoothness and anti-skid properties.

Despite numerous studies highlighting the benefits of perceived aesthetics in enhancing park usage, walking, physical activities, and psychological well-being, no evidence was found in this research to suggest that aesthetics significantly influence social interactions within parks. For instance, a qualitative interview study on parks designed for older adults identified organized activities and aesthetics as crucial for social interaction [43], and that visually appealing natural and artificial environments are known to enhance social life in small urban areas [102]. Differences in findings may stem from variations in research methods, geographic climates, cultural contexts, and target populations. This study was conducted during the summer, and the high number of mosquitoes near the water features may have led to some negative feelings. Additionally, since older adults’ social interactions often involve participation in or observation of others’ activities, amenities may hold more significance than visual appeal.

Ultimately, the study’s results indicate a significant association between park use patterns and social interactions. However, a direct causal link to changes in social interactions cannot be inferred due to the confounding effects of other variables. One possible explanation for this result is that frequent park visits by older adults prompted more opportunities for encounters and interactions, especially in free outdoor spaces. These frequent visits could be driven by activities, scenery, and different people, offering regular social engagement and the chance to build consistent social networks. For instance, some older adults partake in self-organized choral activities six days a week (with Fridays off), enriching their lives and enhancing the spiritual fulfillment derived from interacting with others, crucial in mitigating social isolation and segregation. Correspondingly, some studies have noted that frequent visits to parks can increase social interactions [52]. Conversely, infrequent visits may diminish the role of green spaces as spaces for social interaction [103], and longer stays in parks can increase the likelihood of social interaction among residents [17].

Overall, the results of this study underscore the significant impact of personal factors (including gender and health status), social cohesion, the physical characteristics of urban parks, and usage patterns on older adults’ social interactions. Table 6 provides a summary of these findings and proposes guidelines aimed at enhancing social interactions in urban parks for older adults, thereby promoting the creation of age-friendly and sustainable urban environments.

Table 6.

Guidelines for enhancing social interactions of older adults in urban parks.

5.2. Joint Effects of Personal, Social, Physical, and Park Use Factors

This study evaluated the impact of personal, social, and physical factors and park use patterns on older adults’ social interactions in urban parks. The results revealed significant roles for all variables, with personal, physical, and social factors exerting a more substantial influence compared to park usage patterns. Furthermore, the explanatory power of the models enhanced progressively with the inclusion of each independent variable, accounting for an increase in variance from 10.8% to 29.8%. These findings have dual implications: first, they deepen our understanding of the complex relationship between people and the environment in urban parks. Secondly, they advise urban planners that concentrating exclusively on the physical layout and amenities of parks is inadequate for enhancing the health and social well-being of older adults. The social interactions of older adults are influenced by various factors. Thus, attention should be paid to developing social environments, like enhancing park social cohesion, necessitating collaboration from multiple stakeholders, including park managers and community volunteers. To address the needs of older adults and optimize their social health benefits, it is strongly recommended that policy developers incorporate strategies aligned with the perceptions and personal experiences of older adults.

5.3. Limitation and Future Research

This study advances the exploration of promoting the social interactions of older adults in urban parks in China, yet limitations should be acknowledged. First, data based on self-reports may introduce biases, limiting the findings’ broad applicability. To mitigate this, future research should employ a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative surveys, qualitative interviews, and objective observations for a more holistic perspective. Additionally, the study’s limited sample size constrained the comprehension of social interaction variances among older adults across different age groups. Therefore, expanding the sample and conducting comparisons are recommended to discern how urban parks affect interactions among older age subgroups. Second, this study did not capture the effects associated with seasonal changes. Conducted in summer, the research could have been influenced by seasonality and weather, thereby limiting the assessment of how environmental changes across seasons affect social interactions in parks. Future research should encompass data from various seasons to better understand these dynamics and devise interventions that consider seasonal and weather variations. Third, the absence of a robust theoretical foundation might have overlooked key factors influencing variable relationships, resulting in endogeneity bias. Future studies should integrate diverse theoretical perspectives via in-depth analyses to build a more comprehensive framework. Finally, the widespread adoption of smartphones and other mobile devices means older adults are increasingly engaging with digital technologies. Exploring how digital technologies facilitate or hinder older adults’ physical social interactions in parks has become crucial. Additionally, investigating how urban park design and management can address the needs of diverse groups, including older adults with disabilities or cognitive impairments, is vital for future research.

6. Conclusions

This study provides recommendations for urban planners and policy makers to better build age-friendly park spaces. The study’s findings indicate that the social interactions of older adults in urban parks are influenced by a variety of factors to differing extents. Although individual factors like socio-demographic characteristics are immutable, modifications to artificially created environments could positively impact an individual’s health. The results will hopefully contribute to a better understanding of older adults’ social interactions in urban parks as well as identify those factors that can facilitate their social interactions. Gender differences and the health status of older adults had the most significant direct effects on social interactions. Functional park features, conditions, and accessibility are more important than aesthetics and safety. Policymakers, park managers, community groups, and older adults themselves should work together to enhance park participation, social cohesion, and social support, thereby fostering the social interaction of older adults. Although the impact on social interaction has been explored from different perspectives, research on older adults remains limited, particularly in the Asian context. This study found some consistent results with previous studies, but we also obtained some new evidence. This study suggests that merely increasing the number of parks and enhancing their quality is insufficient for fostering active aging in urban green spaces. Integrating older adults’ perceptions and needs, and acknowledging the influence of individual contexts and sociocultural factors, is essential to develop effective strategies for supporting their social well-being and quality of life. This integrated strategy not only aligns with the principles of sustainable development but also highlights the importance of developing inclusive, healthy, and interactive urban green spaces that offer support and opportunities for older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and N.Z.M.; methodology, H.C., N.Z.M. and Y.W.; software, H.C. and Y.W.; investigation, H.C. and Y.W.; formal analysis, H.C. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, N.Z.M.; supervision, N.Z.M.; project administration, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the School of Housing, Building, and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Malaysia, for supporting this study and the PhD research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eberstadt, N. China’s demographic prospects to 2040 and their implications: An overview. Psychoanal. Psychother. China 2020, 3, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, E.R. Environments for healthy ageing: A critical review. Maturitas 2009, 64, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Age UK. Safeguarding the Convoy: A Call to Action from the Campaign to End Loneliness; Age UK: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; Shankar, A.; Demakakos, P.; Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Merom, D.; Bull, F.C.; Buchner, D.M.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A. Updating the evidence for physical activity: Summative reviews of the epidemiological evidence, prevalence, and interventions to promote “active aging”. Gerontologist 2016, 56, S268–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, A.P.; Richards, S.H.; Greaves, C.J.; Campbell, J.L. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. Analysis on the Influencing Factors of Mental Health of the Elderly—Empirical Analysis Based on CGSS2017 Data. Aging Res. 2023, 10, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults—A mental health/public health challenge. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 990–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, L.C.; Glonek, G.F.V.; Luszcz, M.A.; Andrews, G.R. Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: The Australian longitudinal study of aging. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B. Social relationships and mortality. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2012, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Global Report on Ageism. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2021/03/9789240016866-eng.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N.; Said, I. Legibility of neighborhood parks as a predicator for enhanced social interaction towards social sustainability. Cities 2017, 61, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992; ISBN 0521359600. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, A. On the Placement and Morphology of Clitics; Center for the Study of Language (CSLI): Stanford, UK, 1995; ISBN 1881526607. [Google Scholar]

- Notthoff, N.; Reisch, P.; Gerstorf, D. Individual characteristics and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Gerontology 2017, 63, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspinall, P.A.; Thompson, C.W.; Alves, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Brice, R.; Vickers, A. Preference and relative importance for environmental attributes of neighbourhood open space in older people. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2010, 37, 1022–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreetheran, M. Exploring the urban park use, preference and behaviours among the residents of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity use and contingent valuation of urban greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K. Urban park visiting habits and leisure activities of residents in Hong Kong, China. Manag. Leis. 2009, 14, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Mäkinen, K.; Schipperijn, J. Tools for mapping social values of urban woodlands and other green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Timperio, A.; Bull, F.; Pikora, T. Understanding physical activity environmental correlates: Increased specificity for ecological models. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2005, 33, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Floyd, M.F. The urban growth machine, central place theory and access to open space. City Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, H.E.A.; Tinsley, D.J.; Croskeys, C.E. Park usage, social milieu, and psychosocial benefits of park use reported by older urban park users from four ethnic groups. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of the Great American Cities; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Easthope, H.; McNamara, N. Measuring Social Interaction and Social Cohesion in a High Density Urban Renewal Area: The Case of Green Square; City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales: Kensington, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle, M. Social behaviour. In Psychology for Social Workers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Van Dillen, S.M.E.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Xu, L. Volunteer service and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults: The mediating role of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S.; Servon, L.J. Gender and Planning: A Reader; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 0813534992. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, L.H. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1315134357. [Google Scholar]

- Dines, N.T.; Cattell, V.; Gesler, W.M.; Curtis, S. Public Spaces, Social Relations and Well-Being in East London; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2006; ISBN 1861349238. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, A.; Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kizuki, M.; Seino, K. Contribution of interaction with family, friends and neighbours, and sense of neighbourhood attachment to survival in senior citizens: 5-year follow-up study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, P.; Kemperman, A.; De Kleijn, B.; Borgers, A. Ageing and loneliness: The role of mobility and the built environment. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lin, T. Built environments, social environments, and activity-travel behavior: A case study of Hong Kong. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 31, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Kamani Fard, A. The impact of legibility and seating areas on social interaction in the neighbourhood park and plaza. Archnet-IJAR 2021, 15, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M. Longitudinal analyses of the effects of age, marriage, and parenthood on social contacts and support. Adv. Life Course Res. 2012, 17, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeroja, P. The Role of Social and Built Environments in Supporting Older Adults’ Social Interaction. Ph.D Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.; Flowers, E.; Ball, K.; Deforche, B.; Timperio, A. Designing parks for older adults: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.A.; Ismail, S.; Mseer, A. Pocket parks for promoting social interaction among residents of Baghdad City. Archnet-IJAR 2020, 14, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijs-Perrée, M.; van den Berg, P.; Arentze, T.; Kemperman, A. Factors influencing social satisfaction and loneliness: A path analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 45, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Macdonald, B.; Hülür, G. Not “the more the merrier”: Diminishing returns to daily face-to-face social interaction frequency for well-being in older age. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2001, 23, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You through the Day; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, P. “Third places” and social interaction in deprived neighbourhoods in Great Britain. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2013, 28, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.K. The right to healthy place-making and well-being. Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of urban parks and their relation to user well-being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shi, S.; Runeson, G. Associations between Community Parks and Social Interactions in Master-Planned Estates in Sydney, Australia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Alalouch, C.; Hartig, T. Assessing restorative components of small urban parks using conjoint methodology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K.; Rivera, E.; Loh, V.; Deforche, B.; Best, K.; Timperio, A. What entices older adults to parks? Identification of park features that encourage park visitation, physical activity, and social interaction. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lin, G. The relationship between urban green space and social health of individuals: A scoping review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 85, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Underlying relationships between public urban green spaces and social cohesion: A systematic literature review. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 24, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E.; Casper, M. A definition of “social environment”. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Broyles, S.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Theall, K.P.; Gustat, J.; Rung, A.L. Integrating social capital into a park-use and active-living framework. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero Peña, J.E.; Kodali, H.; Ferris, E.; Wyka, K.; Low, S.; Evenson, K.R.; Dorn, J.M.; Thorpe, L.E.; Huang, T.T.K. The Role of the Physical and Social Environment in Observed and Self-Reported Park Use in Low-Income Neighborhoods in New York City. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 656988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruijsbroek, A.; Mohnen, S.M.; Droomers, M.; Kruize, H.; Gidlow, C.; Gražulevičiene, R.; Andrusaityte, S.; Maas, J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Triguero-Mas, M.; et al. Neighbourhood green space, social environment and mental health: An examination in four European cities. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Lang, F.R. Psychological aging: A contextual view. In Handbook of Models for Human Aging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 881–895. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, G.R.; Rock, M.; Toohey, A.M.; Hignell, D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health Place 2010, 16, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, M.; LaValley, M.P.; Alheresh, R.; Keysor, J.J. Which Features of the Environment Impact Community Participation of Older Adults? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 957–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derose, K.P.; Han, B.; Williamson, S.; Cohen, D.A. Racial-Ethnic Variation in Park Use and Physical Activity in the City of Los Angeles. J. Urban Health 2015, 92, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.J.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, F.; Li, F.H.; Wang, Z.Y. Influence of the built environment of Nanjing’s Urban Community on the leisure physical activity of the elderly: An empirical study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillsdon, M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Ebrahim, S.; Morris, J.N. Physical activity in older women: Associations with area deprivation and with socioeconomic position over the life course: Observations in the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panter, J.; Jones, A.; Hillsdon, M. Equity of access to physical activity facilities in an English city. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Liang, C.; Lucas, J.; Cheng, W.; Zhao, Z. The influence of income and social capital on the subjective well-being of elderly Chinese people, based on a panel survey. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.; Butt, I.; Peh, K.S. The importance of green spaces to public health: A multi-continental analysis. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 7); National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- CJJ/T85-2017; Standard for Classification of Urban Green Space. The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Announcement: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Effects of physical and psychological factors on users’ attitudes, use patterns, and perceived benefits toward urban parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 51, 126691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.C. Retirement income security: Past, present, and future. Gener. J. Am. Soc. Aging 1997, 21, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N. Legibility of neighborhood parks and its impact on social interaction in a planned residential area. Archnet-IJAR 2016, 10, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubben, J.; Blozik, E.; Gillmann, G.; Iliffe, S.; Von Kruse, W.R.; Beck, J.C.; Stuck, A.E. Performance of an abbreviated version of the lubben social network scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Levy-Storms, L.; Chen, L.; Brozen, M. Parks for an aging population: Needs and preferences of low-income seniors in Los Angeles. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Bentsen, P.; Troelsen, J.; Toftager, M.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between physical activity and characteristics of urban green space. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A.; Wiedemann, T. A monitoring tool for the provision of accessible and attractive urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, Z.; Feng, L.; Fan, Z. Beyond Accessibility: A Multidimensional Evaluation of Urban Park Equity in Yangzhou, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Rethinking Planning for Urban Parks: Accessibility, Use and Behaviour; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, B.; Han, L.; Mei, R. The motivation and factors influencing visits to small urban parks in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempen, G.; Van Eijk, L.M. The psychometric properties of the SSL12-I, a short scale for measuring social support in the elderly. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 35, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, A.J.; Baker, B.L.; Benfield, J.; Hickerson, B.; Mullenbach, L.E. A Systematic Evaluation of Bartram’s Garden and Mile: Mid-renovation Study Results; Unpublished Report; William Penn Found: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, S.L.; Webster, N.; Agans, J.P.; Graefe, A.R.; Mowen, A.J. Engagement, representation, and safety: Factors promoting belonging and positive interracial contact in urban parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Wen, F.; Golinelli, D.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Cohen, D.A. Measurement Properties of a Park Use Questionnaire. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Nordin, N.A.; Aini, A.M. Urban Green Space and Subjective Well-Being of Older People: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; He, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xue, C. Social Interaction in Public Spaces and Well-Being among Elderly Women: Towards Age-Friendly Urban Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, T.; Pearson, E.; CRISP, D.; Butterworth, P.; Anstey, K. Neighbourhood Characteristics and Ageing Well: A Survey of Older Australian Adults; Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2012; ISBN 098712496X.

- De Vries, S.; Van Dillen, S.M.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Streetscape greenery and health: Stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 94, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.; Kwan, M.-P.; Chen, F.; Lin, R. Impacts of individual daily greenspace exposure on health based on individual activity space and structural equation modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.S.; Sullivan, W.C.; Wiley, A.R. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 832–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, R.L.; Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E. Where does community grow? The social context created by nature in urban public housing. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Chaudhury, H.; Michael, Y.L.; Campo, M.; Hay, K.; Sarte, A. A photovoice documentation of the role of neighborhood physical and social environments in older adults’ physical activity in two metropolitan areas in North America. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Clarys, P.; Nasar, J.; Salmon, J.; Goubert, L.; Deforche, B. Street characteristics preferred for transportation walking among older adults: A choice-based conjoint analysis with manipulated photographs. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassina, L.; Fredianelli, L.; Menichini, I.; Chiari, C.; Licitra, G. Audio-visual preferences and tranquillity ratings in urban areas. Environments 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Markevych, I.; Tilov, B.G.; Dimitrova, D.D. Residential greenspace might modify the effect of road traffic noise exposure on general mental health in students. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeland, K.; Dübendorfer, S.; Hansmann, R. Making friends in Zurich’s urban forests and parks: The role of public green space for social inclusion of youths from different cultures. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.M.; Evenson, K.R.; Cohen, D.A.; Cox, C.E. Comparing perceived and objectively measured access to recreational facilities as predictors of physical activity in adolescent girls. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikpour, A.; Yarahmadi, M. Recognizing the components of street vitality as promoting the quality of social life in small urban spaces Case study: Chamran Street, Shiraz. Sustain. City 2020, 3, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, A. The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).