International Legal Framework for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries: Challenges and Prospects in Governing Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) under Sustainable Development Goal 14

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ocean and Fisheries Policy (and Literature) Review: Current Challenges

2.1. Interpretation of the IEL for the Governance of LMEs

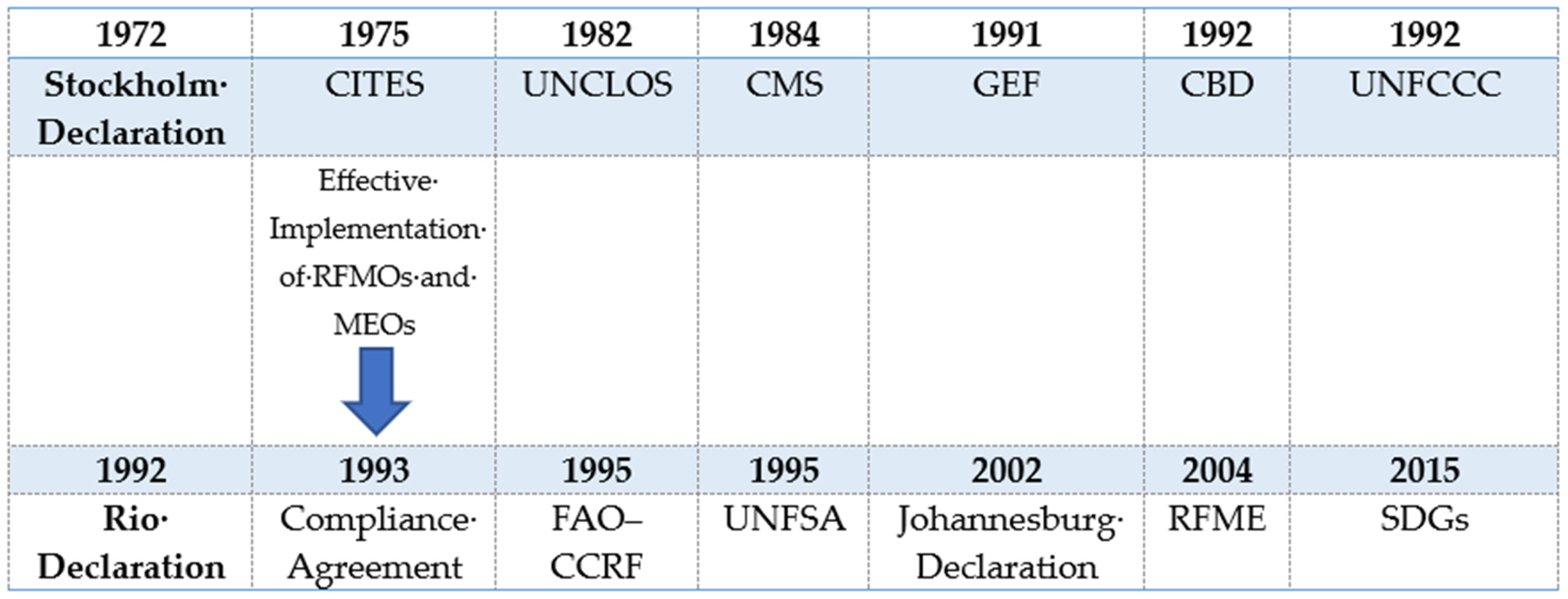

2.2. United Nations Policies for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries

2.3. MEAs Governing LMEs

3. Legal and Theoretical Framework—Application of Methodology

3.1. Framework

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Analysis

3.3.1. Analysis of the Challenges in the Indian Ocean Region

3.3.2. Challenges in the Pacific Ocean

3.3.3. Challenges in the Atlantic Ocean

3.3.4. Challenges in the Arctic Ocean

4. Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water): Prospects and Way-Forward

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zulfiqar, K.; Butt, M.J. Preserving Community’s Environmental Interests in a Meta-Ocean Governance Framework towards Sustainable Development Goal 14: A Mechanism of Promoting Coordination between Institutions Responsible for Curbing Marine Pollution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffoley, D.; Baxter, J.M.; Amon, D.J.; Claudet, J.; Downs, C.A.; Earle, S.A.; Gjerde, K.M.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Koldewey, H.J.; Levin, L.A. The Forgotten Ocean: Why COP26 Must Call for Vastly Greater Ambition and Urgency to Address Ocean Change. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennan, M.; Morgera, E. The Glasgow Climate Conference (COP26). Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2022, 37, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. 1973. (U.N. Doc. A/Conf.48/14/Rev. 1). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea. 1982. (Came into Force on 16 November 1994, (1833 UNTS 397)). Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals; (Enforced 1991), (UNTS 1651; 1983). Available online: https://www.cms.int/#:~:text=The%20Convention%20on%20Migratory%20Species,migratory%20animals%20and%20their%20habitats (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; (Enforced 1975); 1973. (993 UNTS 243). Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/text.php (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- United Nations Conference Declaration on Environment and Development; 1992. (UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26 (vol. I)). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Biagini, B.; Bierbaum, R.; Stults, M.; Dobardzic, S.; McNeeley, S.M. A Typology of Adaptation Actions: A Global Look at Climate Adaptation Actions Financed through the Global Environment Facility. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, 2000. (Enforced—2004) (2275 UNTS 43). Available online: Https://Treaties.Un.Org/Pages/showDetails.Aspx?Objid=0800000280074802 (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Coll, M.; Libralato, S.; Pitcher, T.J.; Solidoro, C.; Tudela, S. Sustainability Implications of Honouring the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, T.; Kalikoski, D.; Pramod, G. Evaluations of Compliance with the FAO (UN) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. 2006. Published by Fisheries Centre Research (Reports 2006 Volume 14 Number 2). Available online: https://iuuriskintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Free-FCRR_2006_14-2-Report-for-53-countries.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Birnie, P. New Approaches to Ensuring Compliance at Sea: The FAO Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int’l Envtl. L. 1999, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner-Kramer, D.M.; Canty, K. Stateless Fishing Vessels: The Current International Regime and a New Approach. Ocean. Coast. LJ 2000, 5, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, 2009. (Enforced 2016) (US Senate Consideration of Treaty Document 112-4). Available online: https://www.Congress.Gov/Treaty-Document/112th-Congress/4/Document-Text (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Butt, M.J.; Zulfiqar, K.; Chang, Y.-C.; Iqtaish, A.M.A. Maritime Dispute Settlement Law towards Sustainable Fishery Governance: The Politics over Marine Spaces vs. Audacity of Applicable International Law. Fishes 2022, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. 1969. (Came into Force 27 January 1980, (1155 UNTS 331)). Available online: https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Chang, Y.-C. Good Ocean Governance. Ocean. Yearb. Online 2009, 23, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. (Came into Force on 29 December 1993, (1760 UNTS 79)). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-8&chapter=27 (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. (1771 UNTS 107). Available online: https://unfccc.int/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Robinson, M. COP-26: The Political Conundrum. Round Table 2021, 110, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. The M/V’ Saiga’ Case on Prompt Release of Detained Vessels: The First Judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Mar. Policy 1998, 22, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de La Fayette, L. ITLOS and the Saga of the Saiga: Peaceful Settlement of a Law of the Sea Dispute. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2000, 15, 355–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fayette, L. International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea: The M/V “Saiga” (No.2) Case (St. Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea), Judgment. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2000, 49, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Butt, M.J.; Iqatish, A.; Zulfiqar, K. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) under the Vision of ‘maritime Community with a Shared Future’ and Its Impacts on Global Fisheries Governance. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, H.S. The Southern Bluefin Tuna Case: ITLOS Hears Its First Fishery Dispute. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 1999, 2, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna, 1993 (Enforced 1994). (1819 UNTS 359). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201819/volume-1819-I-31155-English.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- MOX Plant Case, Ireland v United Kingdom. 2003. (Order No 3, (2003) 126 International Law Reports 310) Special Arbitral Tribunal Constituted under the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Available online: https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-10/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- The “Volga”, Russian Federation v Australia. (Prompt Release, ITLOS Case No 11, International Courts of General Jurisprudence 344 (ITLOS 2002)). Available online: https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-11/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, 1980 (Enforced 1982). (1329 UNTS 47). Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention-text (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area. (Advisory Opinion, ITLOS Case No 17, (2011) ITLOS Rep 10, International Courts of General Jurisdiction 449 (ITLOS 2011)). Available online: https://www.itlos.org/index.php?id=109 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Becker, M.A. Request for an Advisory Opinion Submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC). Am. J. Int. Law 2015, 109, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Obligations and Liability of Sponsoring States Concerning Activities in the Area: Reflections on the ITLOS Advisory Opinion of 1 February 2011. Neth. Int. Law Rev. 2013, 60, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, S. The South China Sea Arbitration and the Finality of ‘Final’ Awards. J. Int. Disput. Settl. 2017, 8, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, C. South China Sea Arbitration and the Protection of the Marine Environment: Evolution of UNCLOS Part Xii Through Interpretation and the Duty to Cooperate. Asian Yearb. Int. Law 2017, 21, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanova, E. Oil Pollution and International Marine Environmental Law. In Sustainable Development–Authoritative and Leading Edge Content for Environmental Management; Curkovic, S., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2012; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boczek, B.A. Global and Regional Approaches to the Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment. Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 1984, 16, 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Oceans and the Law of the Sea; Report of the Secretary-General; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/437569?ln=en (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ship (MARPOL 73/78). 1973. (Came into Force on 26 November 1983, (1340 UNTS 184)). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx#:~:text=The%20International%20Convention%20for%20the,from%20operational%20or%20accidental%20causes (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- International Maritime Organization. Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter; 26 UNTS 2403; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP the Global Environmental Agenda Annual Report; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Environment, U.N. Why Does Global Clean Ports Matter? Available online: http://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/transport/what-we-do/global-clean-ports/why-does-global-clean-ports-matter (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Telesetsky, A. UN Food and Agriculture Organization: Exercising Legal Personality to Implement the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. In Global Challenges and the Law of the Sea; Ribeiro, M.C., Loureiro Bastos, F., Henriksen, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Dabban, H.; van Koppen, C.S.A.; van Tatenhove, J.P.M. Regional Convergence in Environmental Policy Arrangements: A Transformation towards Regional Environmental Governance for West and Central African Ports? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 163, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes, V.; Arenas-Granados, P.; Barragán-Muñoz, J.M. Regional Public Policy for Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Central America. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 186, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes-Dabban, H.; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. The Influence of the Regional Coordinating Unit of the Abidjan Convention: Implementing Multilateral Environmental Agreements to Prevent Shipping Pollution in West and Central Africa. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2018, 18, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, S. UNCLOS and Its Limitations as the Foundation for a Regional Maritime Security Regime. Korean J. Def. Anal. 2007, 19, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Summary Report: Seventeenth Meeting of UN-Oceans; Reports of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2018; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Legal Affairs. Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction; Office of the Legal Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. Comments on FAOs State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA 2016). Mar. Policy 2017, 77, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosch, G.; Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. The 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries: Adopting, Implementing or Scoring Results? Mar. Policy 2011, 35, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; United Nations Development Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Shamsuddoha, M. Coastal and Marine Conservation Strategy for Bangladesh in the Context of Achieving Blue Growth and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 87, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J. The Role of the International Law in Shaping the Governance for Sustainable Development Goals. J. Law Political Sci. 2021, 28, 95–164. [Google Scholar]

- Colard-Fabregoule, C. Chapter 7—Maritime Spatial Planning: A Means of Organizing Maritime Activities Measured Iin Terms of Sustainable Development Goals. In Global Commons: Issues, Concerns and Strategies; Pillai, M.B., Dore, G.G., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: New Delhi, India, 2020; p. 95. ISBN 978-93-5388-362-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, F.; Shen, B. Progress and Prospects of China in Implementing the Goal 14 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2019, 07, 1940006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinan, H.; Bailey, M. Understanding Barriers in Indian Ocean Tuna Commission Allocation Negotiations on Fishing Opportunities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, Z. Incorporating Taiwan in International Fisheries Management: The Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement Experience. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 2017, 48, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, C. Redesigning Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance for 21st Century Sustainability. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsford, D.; Ziegler, P.; Maschette, D.; Sumner, M. Bottom Fishing Impact Assessment (BFIA) for Planned Fishing Activities by Australia in the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) Area–2020 Update. In Proceedings of the 5th Meeting of the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) Scientific Committee, Phuket, Thailand, 25–29 June 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- van der Elst, R.P.; Groeneveld, J.C.; Baloi, A.P.; Marsac, F.; Katonda, K.I.; Ruwa, R.K.; Lane, W.L. Nine Nations, One Ocean: A Benchmark Appraisal of the South Western Indian Ocean Fisheries Project (2008–2012). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALI, G. China–Pakistan Maritime Cooperation in the Indian Ocean. Issues Stud. 2019, 55, 1940005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereynier, Y.L. Evolving Principles of International Fisheries Law and the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 1998, 29, 147–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Oozeki, Y.; Takasaki, K.; Saito, T.; Uehara, S.; Miyahara, M. Transshipment Activities in the North Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area. Mar. Policy 2022, 146, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S. Fur Seals and the Bering Sea Arbitration. J. Am. Geogr. Soc. N. Y. 1894, 26, 326–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqorau, T. Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2009, 24, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.G.; Hare, S.R. Effects of Climate and Stock Size on Recruitment and Growth of Pacific Halibut. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2002, 22, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Croston, J.L. WTO Scrutiny v. Environmental Objectives: Assessment of the International Dolphin Conservation Program Act. Am. Bus. LJ 1999, 37, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, D.J.; Fang, L.; Hipel, K.W.; Kilgour, D.M. The Pacific Salmon Treaty: A Century of Debate and an Uncertain Future. Group Decis. Negot. 2005, 14, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 1992 Convention for the Protection of Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (Paris), 22 September 1992, Came into Force on 25 March 1998, (32 ILM (1992)), 1068. Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_29147/convention-for-the-protection-of-the-marine-environment-of-the-north-east-atlantic-ospar-convention#:~:text=The%20OSPAR%20Convention%20is%20the,restore%20marine%20areas%20which%20have (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Wilewska-Bien, M.; Anderberg, S. Reception of Sewage in the Baltic Sea—The Port’s Role in the Sustainable Management of Ship Wastes. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen-Alonso, M.; Pepin, P.; Fogarty, M.J.; Kenny, A.; Kenchington, E. The Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Roadmap for the Development and Implementation of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: Structure, State of Development, and Challenges. Mar. Policy 2019, 100, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.J.; Hansen, S.C.; Gale, J. Overview of Discards from Canadian Commercial Groundfish Fisheries in Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) Divisions 4X5Yb for 2007–2011; Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS): Moncton, NB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Chiriboga, O.R. The American Convention and the Protocol of San Salvador: Two Intertwined Treaties: Non-Enforceability of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the Inter-American System. Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2013, 31, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namnum, S. The Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles and Its Implementation in Mexican Law. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2002, 5, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, L.; Mahon, R.; McConney, P. Applying the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) Governance Framework in the Wider Caribbean Region. Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, W.P. Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution. Environ. Policy Law 1976, 2, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, E.A.; Popattanachai, N.; Ibe, C. Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution 1992. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Environmental Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-C. Chinese Legislation in the Exploration of Marine Mineral Resources and Its Adoption in the Arctic Ocean. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdy, A. The Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean: An Overview. Ocean. Yearb. Online 2019, 33, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources: A Five-Year Review. Int. Comp. Law Q. 1989, 38, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convey, P.; Peck, L.S. Antarctic Environmental Change and Biological Responses. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaz0888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-C. The Sino-Canadian Exchange on the Arctic: Conference Report. Mar. Policy 2019, 99, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaso, A.A. Oceans Policy as a Sustainable Tool for the Regulation of the Marine Environment. Int’l J. Adv. Leg. Stud. Gov. 2012, 3, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Aukes, E.; Lulofs, K.; Bressers, H. (Mis-)Matching Framing Foci: Understanding Policy Consensus among Coastal Governance Frames. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 197, 105286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J. Book Review: Kum-Kum Bhavnani, John Foran, Priya A. Kurian and Debashish Munshi, Climate Futures: Reimagining Global Climate Justice. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2021, 23, 14649934211028718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J.; Zulfiqar, K.; Chang, Y.-C. The Belt and Road Initiative and the Law of the Sea, Edited by Keyuan Zou. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2021, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomariyah. Oceans Governance: Implementation of the Precautionary Approach to Anticipate in Fisheries Crisis. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 14, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| ABNJ | Areas Beyond Nations Jurisdiction |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CCAMLR | Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources |

| CCRF | Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries |

| CCSBT | Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna |

| CITES | Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| CMS | Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals |

| COP | Conference of Parties |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GEF | Global Environmental Facility |

| ICJ | International Court of Justice |

| IEL | International Environmental Law |

| ITLOS | International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea |

| IUU-Fishing | Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing |

| Johannesburg Declaration | World Summit on Sustainable Development |

| LDCs | Least Developed Countries |

| LMEs | Large Marine Ecosystems |

| MEOs | Multilateral Environment Organizations |

| OSPAR Convention | Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Northeast Atlantic |

| PMSA | Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing |

| RFME | Declaration on Responsible Fisheries in Marine Ecosystems |

| RFMOs | Regional Fisheries Management Organizations |

| Rio Declaration | United Nations Declaration on Environment and Development |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDG 14 | Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) |

| SIDS | Small Island Developing States |

| SRFC | Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission |

| Stockholm Declaration | United Nations Conference on the Human Environment |

| The Compliance Agreement | Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas |

| UNCLOS | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Program |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| UNFSA | United Nations Convention on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks |

| Vienna Convention | Vienna Convention on Law of Treaties |

| SDG 14 | Legal Basis within SDG 14 | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention or significant reduction of marine pollution, effective regulation and harvest of fisheries; ending overfishing, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and destructive fishing practices; implement science–policy governance mechanisms; and prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing; eliminate subsidies that contribute to IUU fishing | Conservation of ten percent of marine areas according to international law (that calls for the best available scientific information) Enhancing the conservation and sustainable use of the ocean and its resources by implementing international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which provides the legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources |

|

| Sub-Region | Fisheries MEAs | Organization | Ocean Governing MEAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Indian Ocean with Strategic Partnership with FAO | Agreement Establishing the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission—1993 | Indian Ocean Tuna Commission | Kuwait Regional Convention for Cooperation on the Protection of the Marine Environment from Pollution (Kuwait Convention)—1983 |

| The Colombo Declaration on the South Asia Cooperative Environment Program (SACEP)—1981 | |||

| High Seas Between Eastern Africa and Western Australia | Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement—2006 | The Southwest Indian Ocean Fisheries Commission/South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Project (SWIOFP)—2006 | Nairobi Convention—1996 |

| The Convention for Cooperation in the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Atlantic Coast of the West and Central Africa Region (Abidjan Convention)—1981 | |||

| Regional Convention for the Conservation of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Environment (Jeddah Convention)—1982 |

| Sub-Region | Fisheries MEA | RFMO | Ocean MEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Pacific | Convention for the Conservation of Anadromous Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean—1993 | North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission | Northwest Pacific Action Plan—1994 |

| North Pacific Fisheries Convention—1953 | Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission—1949 | Convention for Cooperation in the Protection and Sustainable Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the North-East Pacific (Antigua Convention)—2002 | |

| North Pacific Fisheries Commission—1970 | |||

| Bering Sea | Convention on the Conservation and Management of Pollock Resources in the Central Bering Sea—1994 | Annual Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation and Management of Pollock Resources in the Central Bering Sea | Southeast Pacific Action Plan—1981 |

| Western and Central Pacific Ocean | Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Convention—1995 | Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission | Nauru Agreement—1982 |

| Western Coastal Areas of USA and Canada | International Pacific Halibut Convention Between USA and Canada—1980 | International Pacific Halibut Commission—1980 | |

| South Pacific Ocean | The Convention on the Conservation and Management of High Seas Fishery Resources in the South Pacific Ocean—2001 | South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization—2003 | Convention for the Protection of the Natural Resources and Environment of the South Pacific Region (Noumea Convention)—1986 |

| Whole Pacific Ocean | Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program—1999 | International Dolphin Conservation Program—1999 | All MEAs |

| The Pacific Salmon Treaty—1985 | Pacific Salmon Commission—1986 |

| Sub-Region | Fisheries MEA | RFMO | Ocean MEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Atlantic | Convention for the Conservation of Salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean—1982 | North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization—1982 | Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea (HELCOM or Helsinki Convention)—1992 The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention)—1992 |

| Northwest Atlantic | Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries—1978 | Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization—1980 | |

| Caribbean Sea | Agreement establishing the Caribbean regional fisheries mechanism—2002 | Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism—2002 | The Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment in the Wider Caribbean Region (Cartagena Convention)—1986 |

| Mediterranean Sea | Agreement for the Establishment of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean—1997 | General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean—1997 | Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona Convention)—1978 Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution (Bucharest Convention)—1996 |

| Whole Atlantic Ocean | Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles—2001 | Multiple Organizations in Atlantic Ocean | All MEAs |

| Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas—1975 | International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas—1975 | ||

| Southeast Atlantic Ocean | Convention On the Conservation and Management of Fishery Resources in the Southeast Atlantic Ocean—2001 | Southeast Atlantic Fisheries Organization—2001 | |

| Western Central Atlantic | Resolution 4/61 of the FAO Council under Article VI of the FAO Constitution—2006 | Western Central Atlantic Fisheries Commission—2006 |

| Sub-Region | Fisheries MEA | RFMO | Ocean MEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Arctic | International Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean—2018 | None | None |

| The Whole Arctic Ocean | Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources—1982 | Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources—1982 | Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic—2013 |

| Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna—1993 | Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna—1995 | ||

| Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation—2017 | IMO—International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters—2017 | ||

| Ottawa Charter—1986 | Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic—2011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.; Butt, M.M.Z.; Lv, Y.-M.; Yan-E-Wang. International Legal Framework for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries: Challenges and Prospects in Governing Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) under Sustainable Development Goal 14. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062566

Zhang S, Wu Q, Butt MMZ, Lv Y-M, Yan-E-Wang. International Legal Framework for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries: Challenges and Prospects in Governing Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) under Sustainable Development Goal 14. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062566

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shijun, Qian Wu, Muhammad Murad Zaib Butt, (Judge) Yan-Ming Lv, and (Judge) Yan-E-Wang. 2024. "International Legal Framework for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries: Challenges and Prospects in Governing Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) under Sustainable Development Goal 14" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062566

APA StyleZhang, S., Wu, Q., Butt, M. M. Z., Lv, Y.-M., & Yan-E-Wang. (2024). International Legal Framework for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries: Challenges and Prospects in Governing Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) under Sustainable Development Goal 14. Sustainability, 16(6), 2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062566