Abstract

This study investigates the influence of psychological factors and socio-demographic characteristics on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. The theory of reasoned action and Hirose’s two-phase decision-making model act as the major informers to develop the research hypotheses. Through an online questionnaire survey, responses were collected from a sample of 275 Japanese consumers who bought organic foods based on environmental consciousness at least once. Structural equation modeling is used to analyze the data. This study shows that the key to promoting actual purchase lies in three factors: social norm, past experience, and willingness to pay (WTP). Attitude towards actual purchase negatively influenced actual purchase, and environmental awareness was the determinant for attitude towards actual purchase but not for actual purchase. Thus, only increasing environmental awareness is not enough to increase the actual purchase. Moreover, we could increase the actual purchase by making an effort to reduce the feelings of the unaffordability and inconvenience of organic foods, which also negatively influence WTP and negatively and indirectly influence actual purchase. This study finds that the behavior execution process is the main driving force influencing actual purchase rather than the attitude development process in terms of psychological factors behind organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness.

1. Introduction

Ethical consumption awareness is increasing gradually worldwide, and much attention has focused on ethical consumers [1,2]. A product that contains a particular ethical concern, such as environmental consciousness, being locally produced, being fair trade, biodiversity conservation, or animal welfare status, is called an ethical product, and individual consumers can choose freely between a conventional and an ethical product [3]. In general, ethical consumers feel responsible for society and can express these feelings using their purchasing behavior [4].

Organic is one of the most recognized claims among ethical foods [5]. Organic foods are grown using composts or other organic materials without the use of agricultural chemicals and fertilizers for no less than two years before sowing and planting [6]. Therefore, organic foods are treated as environmentally friendly, nutritious, and safe [5,7].

There are two common motives for buying organic foods. In general, the most common motive for buying organic food is personal health concern (non-ethical reason) followed by concern for the environment (ethical reason) [8]. The number of consumers who have a positive attitude toward purchasing organic food due to environmental concern is increasing. One study found that over fifty percent of respondents across eight countries consider products’ “environmental concern” an ethical issue when making their purchasing decision [9].

However, researchers found that though people have a positive attitude towards the actual purchase of organic food, they did not buy it because they gave more importance to good taste rather than the organic criterion [10] or because of their perception of the expensiveness of organic foods compared to conventional foods [8]. This phenomenon is generally known as the “attitude–behavior gap” or the “green gap” [11]. Johnstone and Tan found that perceptions towards the concept of “green” may influence consumers’ intentions to purchase green products.

Hirose suggested that developing an environmentally friendly attitude (environmental perception) and executing environmentally conscious behavior depend on three factors: the time gap between attitude and behavior, environmentally conscious behaviors associated with that particular attitude, and the comfort and convenience of that behavior [12]. Therefore, the examination of organic food purchasing behavior with a model that incorporates the attitude–behavior gap is essential. Through the proper study of growing environmental concerns among consumers, it is possible to promote the potential future market of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. However, as far we know, there is a lack of theoretical research on the consumer behavior of purchasing organic food for environmentally conscious reasons incorporating the attitude–behavior gap. Understanding behavioral insights can help marketers and policymakers to obtain a deeper understanding of this behavioral mechanism to provide policy implications to promote organic food consumption for environmentally conscious reasons.

This work is presented in six sections. The theoretical framework is presented in Section 2 followed by the materials and methodology used in Section 3. The research findings are presented and discussed in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the work done, and some points for future research are presented in Section 6.

2. Theoretical Framework

Based on the reasoned action theory [13], Seligman and Ferigan’s reasoned action model was developed with the presumption that a behavior depends on the benefit of that particular behavior. While they gave more attention to factors that directly influence behavior, they did not incorporate the process of how an environmentally friendly attitude grows [14]. Based on those earlier models, ref. [12] developed a two-phase decision-making model with the presumption that the decision-making process is developed before performing an environmentally conscious behavior.

Additionally, ref. [12] argued that environmental perception is not enough to execute consumers’ environmentally conscious behavior. Consumers’ psychological driving factors are two-fold—the attitude development process and the execution of environmentally conscious behavior (actual behavior)—and the actual behavior can be observed when the behavior execution process exceeds the attitude development process.

Voon et al. in 2011 developed a model based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (an extension of the theory of reasoned action) by Ajzen in 1991 to promote organic food consumption in Malaysia. They added people’s willingness to pay (WTP) for organic food as a factor and examined the effect of WTP on the actual purchase of organic foods [15]. Therefore, we incorporated both Hirose’s two-phase model, specifically the perceived effectiveness variable, and Voon et al.’s model. The summary of factors used in our model with measurement items is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of factors with measurement items.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

We conducted an online questionnaire survey to collect data in Japan (among 47 cities). We purposively collected nation-wide samples of 1100 with the same proportion of male and female and also for the age ranges of people in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. We first explained the meaning of ethical consumption and the ethical issues related to food, such as organic, animal welfare, biodiversity, and fair trade. Our target consumers were those who have bought organic foods based on environmental consciousness at least once. We asked, “When grocery shopping in general, how often do you buy ethical products based on ethical consciousness?” We generated 275 samples who reported the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness for the data analysis.

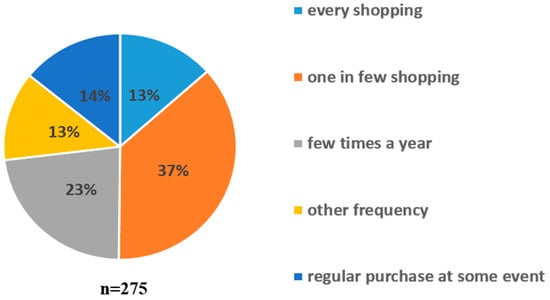

Dependent variable: self-reported actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. We created our dependent variable based on the information about future purchasing frequencies of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. Figure 1 shows that 13% of the respondents would purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness during every shopping trip, 37% would purchase organic food every few shopping trips, 23% would purchase organic food a few times a year, 13% would purchase organic food at a frequency other than those listed above, and 14% of them would not purchase organic food during general grocery shopping but would purchase organic food during an event (regular purchase at some events).

Figure 1.

Reported actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness in the future.

In our analysis, we used these frequencies as a dummy variable where we combined purchasing organic foods based on environmental consciousness during every shopping trip and purchasing organic foods based on environmental consciousness every few shopping trips, i.e., would purchase regularly = 1 and would not purchase regularly = 0. It appears that 50% of the respondents would purchase organic foods based on environmental consciousness regularly. Table 2 represents a description of the dependent and independent variables.

Table 2.

Variables’ description.

Table 3 shows a descriptive summary of the variables and socio-demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Descriptive summary of variables and socio-demographic characteristics (n = 275).

The descriptive summary shows that 50% of respondents would regularly purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness. Most of the respondents were 50 years old, 44 percent of them were male, most of them had an income of JPY 4 to 6 million (USD 26,995.38 to USD 40,511.10), and 61 percent had a past experience of purchasing organic foods based on environmental consciousness. Finally, the mean willingness to pay for organic foods was JPN 1430.55 (approx. USD 13.3) when we compared it with conventional foods at JPN 1000 (approx. USD 9.3).

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Path Analysis of SEM

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with all observed variables is called path analysis. Path analysis is a particular case of SEM with the only structural model but no measurement model. That is, path analysis is the application of SEM without latent variables. In path analysis, latent variables of the structural model are replaced with observed variables to find the causal relationships between observed variables. Then, the structural model becomes the well-known simultaneous equation model shown in Equation (1)

where is the intercept; and are vectors of observed endogenous and observed exogenous variables, respectively; is the matrix of coefficients of the variables; is the matrix of coefficients of the variables; and is the vector of errors [29].

3.2.2. Hypotheses of the Study

Based on previous studies, we propose the following hypotheses:

- Perceived effectiveness

The concept of perceived consumer effectiveness was initially defined in a prior study [30] as the measurement of one’s belief in the results of one’s actions. A previous study found that perceived effectiveness positively influences attitude towards pro-environmental behavior such as waste REDUCTION [18]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.

Perceived effectiveness has a positive and direct effect on attitude towards actual purchase. Attitude towards actual purchase mediates the effect of perceived effectiveness on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness. As perceived effectiveness to benefit the environment becomes more positive, an individual’s attitude towards the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness becomes more positive.

- Attitude towards the actual purchase

Attitude is a psychological and perceptional construct which represents an individual’s willingness to act or react in a certain way [31] and is based on the individual’s feelings (thoughts), beliefs, and emotions (affections) towards the issue [15,17,20]. In other words, attitude is measured by pleasant/unpleasant, boring/interesting, good/bad, unfavorable/favorable, enjoyable/unenjoyable, useful/useless, harmful/harmless [32]. The study concluded that attitude towards the environment positively influences environmentally conscious behavior [33]. Attitude towards waste reduction has a positive effect on waste reduction behavior by children [12]. Attitude towards organic foods has a positive and direct effect on the actual purchase of organic food [34]. Therefore, we may hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2.

Positive attitude towards the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness has a positive and direct impact on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- Perceived effectiveness

A previous study revealed that perceived effectiveness positively influences pro-environmental behavior [26]. A study also found that perceived effectiveness is the determinant of three pro-environmental behaviors: the purchase of green products, good citizenship behavior, and environmental activism [27]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3.

Perceived effectiveness (environmental perception) has a direct positive impact on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- Socio-demographic characteristics

The purchase of organic food varies for different cultural and demographic factors [7]. A previous study found that older people are more likely to purchase organic food [35]. Hence our next hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 4.

Age has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness, and men are more likely to purchase organic foods [35,36], thus

Hypothesis 5.

Being male has a direct positive effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- Social norm

A social norm consists of two influences: (1) the informational norm to enhance knowledge and (2) the norm to conform to the expectations of others [24,25]. In our study, we combined the subjective norm and moral norm with the social norm. The subjective norm concerns the perceived social pressures to undertake or not undertake a behavior [16,37]. Moreover, the moral norm is the personal feelings of moral responsibility or obligation to perform a particular behavior, which may significantly contribute to explaining the variance in the behavior [16,38]. Once the moral norm is activated, people feel obligated to engage in environmentally conscious behavior [39]. So, social norm in this study indicates the moral norm, knowledge, and social pressure. A study analyzing energy-saving behavior among university students in Vietnam identified social norm as the most important determinants for energy-saving behavior [40]. The social norm has also been shown to have a direct positive influence on waste reduction behavior [18]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6.

The social norm has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- WTP (Willingness to Pay)

WTP is the immediate antecedent of the actual purchase of organic food [15]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 7.

WTP has a direct positive effect on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness.

- Past experience

The previous study found that the purchase of organic food depends on past purchasing behavior [41]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 8.

Past experience has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- Income

An organic food study in Thailand indicated that higher family income motivates people to purchase organic foods [35]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 9.

Household income has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness.

- Unaffordability and inconvenience perception

Perceived behavioral control has an effect on attitude towards actual behavior [16]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 10.

Unaffordability and inconvenience perception has a direct negative impact on attitude towards actual purchase.

- Indirect effect

Additionally, subjective norms influence attitude towards actual behavior [16]. A previous study on organic food consumption in India also confirmed that subjective norms influence the consumer attitude towards organic food products [7]. Hence, our next hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 11.

The social norm has a positive and direct influence on attitude towards actual purchase. Attitude mediates the effect of the social norm on actual purchase. As the social norm becomes positive, the attitude towards actual purchase becomes positive.

In addition, a previous study identified a significant positive effect on WTP [15]. Thus,

Hypothesis 12.

Attitude towards actual purchase has a direct positive impact on WTP. WTP mediates the effect of attitude towards actual purchase on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness. As WTP increases, the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness increases.

Performing a behavior can be predicted by perceived behavioral control [16]. The higher monetary cost was identified as the main barrier to purchasing organic food [42]. Therefore,

Hypothesis 13.

Perception of unaffordability and inconvenience has a negative effect on WTP.

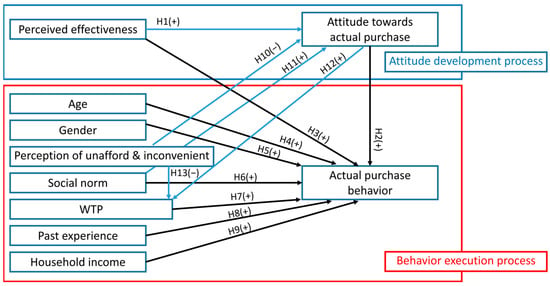

A hypothetical model developed based on above hypotheses H1–H13 is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Initial hypothesized model. Note: Squares denote observed variable, black lines indicate direct effects, and blue lines indicate indirect effects. Each hypothesis (H) represents the relationship between two variables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

Before the estimation of the initial hypothetical model, an exploratory factor analysis (shown in Appendix A) was conducted to measure factors with the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha. This study extracted four factors—attitude towards the actual purchase (awareness), social norm (social pressure), perception of unaffordability and inconvenience (cost and convenience), and perceived effectiveness (environmental awareness)—based on an eigenvalue greater than 1. All loadings below 0.4 were dropped, and the factor analysis was then recalculated. We used the maximum likelihood extraction method and the Promax rotation method. All questionnaire items were highly loaded for each factor. Specifically, the reliability coefficient for attitude towards actual purchase was 0.869, social norm was 0.766, perception of unaffordability and inconvenience was 0.745, and perceived effectiveness was 0.816. All the alpha values were greater than the threshold of 0.70, indicating that all questions reliably measured each factor [43].

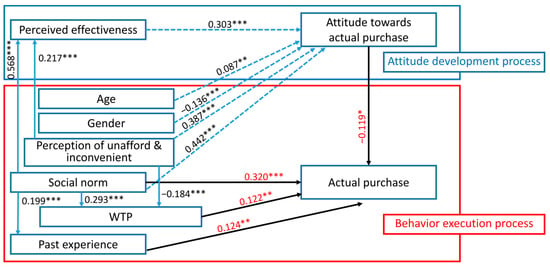

The present study applied AMOS 22.0 with the maximum likelihood method to evaluate the initial hypothesized model. The goodness of fit indices of the initial model indicated a poor fit. Thus, to improve model fit, the initial model was recalculated based on modification indices that were computed by AMOS, and nonsignificant effects were also deleted. Compared to the initial model, the revised model with the fit indices chi-square = 1.072, RMSEA = 0.016, CFI = 0.996, GFI = 0.977, AGFI = 0.960, and NFI = 0.941 indicated a better fit. Thus, we determined that our revised model is statistically fit for our data. Figure 3 shows the estimated revised model with standardized path coefficients.

Figure 3.

Estimated standardized path coefficients for the revised model. Note: *, **, *** indicates a p-value less than 0.1, 0.05, 0.001, respectively, and all variables are observed, so rectangles are used to represent the variables. Black solid lines indicate a direct effect on actual purchase, blue lines indicate an indirect effect on actual purchase, and blue dotted lines indicate an effect on attitude towards actual purchase. Numbers (path coefficients) indicate the degree of relationship; n = 275.

Our model was able to explain 13.4% of the variance in the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. Figure 3 shows the estimated standardized path coefficients for the revised model. Consumers’ attitude towards actual purchase was associated with perceived effectiveness, perception of unaffordability and inconvenience, social norm, and their socio-demographic characteristics: gender and age.

Estimation of the standardized direct and indirect effects of each predictor on actual purchase (Table 4) determined the relative contribution of each predictor to actual purchase. If we consider the absolute standardized total effects, social norm is the most important predictor for the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis tests and effect analysis of actual purchase for the revised model.

Table 4 shows the results of the hypothesis tests and the direct and indirect effects of predictors on actual purchase.

4.2. Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the determinants of the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness in Japan. By analyzing the data with structural equation modeling, the findings suggest the following determinants of the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness:

Perceived effectiveness: Respondents with a greater sense of the effectiveness of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness to benefit the environment showed a direct positive effect on attitude towards the actual purchase (0.303 ***) and an indirect negative effect on actual purchase through attitude towards actual purchase. Thus, it was a determinant for the attitude towards actual purchase but not for the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness. This result supports Hirose’s two-phase general model [12]. Thus, we rejected H3. One of the reasons for why perceived effectiveness (environmental perception) did not appear as a determinant of actual purchase is because the perception of the unaffordability and inconvenience of organic foods (such as organic food is expensive, inconvenient, and available in limited stores) has a direct positive significant effect on perceived effectiveness (0.217 ***). This means that the feeling that organic foods are unaffordable and inconvenient could influence whether an individual believes that they can help conserve the environment by their organic food purchasing based on environmental consciousness. This finding confirms the finding of Richerd et al. [8].

Thus, to promote the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness, increasing the environmental perception/awareness is not enough; we should focus on other important key factors. In this study, social norm, past experience, and WTP directly and positively affected the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness.

Attitude towards the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness: This had a negative influence on actual purchase, which means that having a positive attitude did not influence the purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. Some previous researchers have also found that having a positive attitude does not lead to actual behavior. For example, one study found that a positive attitude towards kitchen waste separation behavior negatively influences actual separation behavior [44]. 2 Hirose showed that adults with a positive garbage reduction attitude did not actually carry out a garbage reduction behavior [18]. One of the reasons for why attitude towards the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness had a negative effect on actual purchase (−0.119 *) may be because the perceived unaffordability and inconvenience of organic food influences this attitude. Even those who feel that purchasing organic foods is inconvenient and unaffordable still have better perceptions of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. However, this seemingly contentious perception influences consumers’ attitudes towards purchasing green products such that a higher attitude negatively impacts the actual purchase.

Social norm: The social norm has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness (0.320 ***). Thus, we accepted H6. The social norm is the most important predictor promoting organic foods consumption based on environmental consciousness (ranks of all predictors are shown in Table 4) in Japan. Increasing social pressure through social media, television, word of mouth, and different programs and informing people about their moral responsibility or moral obligation could enhance an individual’s sense of moral responsibility regarding organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness, which can help to build the social norm. Providing knowledge about the importance of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness and promoting the potential benefits of these product on a larger scale can also help in this regard. The moral norm needs to be visible because an individual need to be aware of it.

Past experience: This has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness (0.124 **). Thus, we accepted H8. From our estimated revised model, Figure 3 shows that the social norm positively influences past experience (0.199 ***). According to previous research, the past behavior of consumers also had a significant positive effect on organic food purchases [41].

Once purchased, it is also found that behavior is habitual and influenced by automated psychological processes rather than by elaborate reasoning [45]. A particular type of behavior is likely to be repeated when outcomes are generally satisfactory. Thus, we should cultivate and encourage consumers’ organic food purchasing behaviors based on environmental consciousness. This results in the conversion of an experience into a habit. For example, manufacturers can provide subscription services for the regular delivery of organic foods.

Further, subtle social pressures that inform and remind people about moral responsibility or obligation and promote the potential benefits of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness could be useful. A reference group based on the social norm could generate self-reinforcing repetition [41]. Marketers of organic foods can facilitate self-reinforcing repetition by sharing the purchase experiences of consumers of organic foods based on environmental consciousness.

WTP: WTP has a direct positive significant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness (0.122 **). This result is consistent with a study in Malaysia which showed that willingness to pay (WTP) for organic food had a significant positive effect on the actual purchase of organic food [15]. Thus, we accepted H7. The social norm had a significant positive effect on WTP (0.293 ***). The perception of unaffordability and inconvenience had a significant negative effect on WTP (−0.184 ***). Therefore, it is possible to increase the WTP for organic products based on environmental consciousness while keeping organic products and conventional products next to each other at the supermarket. Increasing social pressure, promoting the potential benefit of organic foods based on environmental consciousness, and changing negative perceptions about the cost and affordability of organic foods can also help to increase the WTP for organic foods based on environmental consciousness.

Perception of unaffordability and inconvenience: This showed an indirect negative significant effect on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. It had a direct positive effect on the perceived effectiveness (0.217 ***) and attitude towards the actual purchase (0.387 ***), which means that people who perceived organic foods as unaffordable and inconvenient still had the perception that organic foods benefit the environment and had a positive attitude towards the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. These results could be the psychological working of a discrepancy between attitude and behavior [10].

This also had a significant negative effect on WTP (−0.184 ***). Thus, we accepted H13. Therefore, unless negative perceptions (organic foods are inconvenient and expensive) are changed, there will always be less WTP. To overcome the perceived inconvenience and unaffordability, we could re-educate people about the effectiveness and importance of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness to benefit the environment.

For the indirect path, all of the variables except social norm are statistically significant and with the expected signs; therefore, the corresponding hypotheses are supported by the data.

The role of socio-demographic variables: Demographic variables such as age and gender have a significant effect on attitude towards actual purchase but not on the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness. Older females have a more positive attitude towards organic foods consumption based on environmental consciousness than men. Household income has a nonsignificant effect on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness. This result is consistent with previous research that found that purchasing organic foods had a small effect on the overall expenditures for food [41]. One consideration is the price premium being small for organic products compared to conventional alternatives; purchasing one organic product may have a small effect on the total expenditures. Therefore, income may not have an effect on food purchasing decisions [41].

Therefore, social norm, WTP, and past experience are the factors that strongly determine the actual purchase of organic foods based on environmental consciousness, and the perceived effectiveness (environmental perception) is a determinant of the attitude towards actual purchase but not the actual purchase. This also means that the behavior execution process is the main driving force influencing the actual purchase rather than the attitude development process. We can conclude that the results of this study support Hirose’s two-phase general decision-making model.

Researchers have also found that despite having a positive attitude towards the actual purchase of organic foods, people did not buy them because they valued the importance of good taste rather than organic criterion [10] and because of their perception of the expensiveness of organic foods compared to conventional foods [8]. This phenomenon is generally known as the “attitude–behavior gap” or the “green gap” [11].

Hirose suggested that developing an environmentally friendly attitude (environmental perception) and executing environmentally conscious behaviors depend on three factors: the time gap between attitude and behavior, environmentally conscious behavior associated with a particular attitude, and comfort and convenience of that behavior [12].

We believe that examining organic food purchasing behavior with a model that incorporates the attitude–behavior gap is important. However, to our knowledge, there is a lack of theoretical research on the consumer purchasing behavior of organic food based on environmental consciousness incorporating the attitude–behavior gap. We would like to contribute the empirical evidence of the attitude–behavior gap in line with the psychological theories behind the attitude–behavior gap. Therefore, we examined in this paper whether the actual behavior is influenced by the behavior execution process rather than the attitude development process. This study newly incorporated the perceived effectiveness (environmental perception) variable in the organic food consumption model.

Understanding behavioral insights can help marketers and policymakers to obtain a deeper understanding of the behavioral mechanism to promote organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness.

5. Conclusions

This research identifies key psychological factors influencing the purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness in Japan. We developed a model combining Hirose’s two-phase attitude–behavior gap model with reasoned action theory to measure actual purchase behavior. Through structural equation modeling, we found that the social norm, willingness to pay, and past experience directly influence actual purchase behavior, while age, gender, perception of affordability and convenience, and the social norm indirectly affect the attitude towards purchase. The social norm emerged as the most influential predictor, followed by past experience and willingness to pay. The attitude towards purchasing based on environmental consciousness and perception negatively influences the actual purchase behavior, confirming Hirose’s model. To promote organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness, enhancing social pressure, promoting moral responsibility, providing positive initial experiences, and changing perceptions about the cost and availability of organic foods are crucial. Marketers and policymakers can utilize these findings to develop effective strategies for promoting organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. These include increasing social pressure, providing positive initial experiences, and re-educating consumers about the benefits of organic food consumption. Additionally, placing organic and conventional products together in supermarkets and offering subscription services can help habituate consumers to purchasing organic foods while reducing perceptions of the unaffordability and inconvenience of organic foods.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Concerning the limitations of this study and future directions for research, future research should test the influence of more predictors on the actual purchase of organic food based on environmental consciousness. Secondly, the sample size was only 275 people, as we aimed to analyze the psychological driving forces of existing organic food consumers who provided reports of having the experience of purchasing organic food previously. Our model was able to explain 13.4% of the variance. In order to increase the R-squared (% of variance explained by the model) of the model, the sample size needs to be increased. Thirdly, for more general and inclusive findings, future studies could include other countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.S. and H.N.; methodology, M.B.S. and H.N.; software, M.B.S. and H.N.; validation, M.Y. and H.N.; formal analysis, M.B.S.; investigation, H.N.; resources, H.N.; data curation, H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.S.; writing—review and editing, H.N., N.H.A.A. and N.A.A.A.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, H.N. and N.A.A.A.; project administration, H.N. and N.A.A.A.; funding acquisition, N.A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Multimedia University, Malaysia, grant number MMUI/230019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

At Kyushu University, Japan (the survey conducted under this University) the questionnaire-based survey without human experiments is exempted from the ethics committee approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Exploratory factor analysis (survey items and loading) (n = 275).

Table A1.

Exploratory factor analysis (survey items and loading) (n = 275).

| Survey Statements | Attitude towards Actual Purchase | Social Norm | Perception of Unaffordability and Inconvenience | Perceived Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| We should be encouraging organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness to society widely. | 0.586 | 0.279 | 0.145 | −0.095 |

| Organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness is good as it can improve society’s awareness about social issues. | 0.843 | −0.027 | 0.005 | −0.034 |

| We can build a better society through organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. | 0.814 | −0.021 | −0.077 | 0.043 |

| Organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness is effective as it is good for society. | 0.852 | −0.033 | −0.055 | −0.008 |

| The concept of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness can help to build up a sense of solidarity in society. | 0.738 | −0.047 | −0.022 | 0.091 |

| Organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness is a good act. | 0.861 | −0.141 | −0.102 | 0.064 |

| Organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness should be promoted more. | 0.866 | −0.004 | −0.086 | 0.020 |

| I would like to know more about organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. | 0.647 | 0.148 | 0.055 | 0.014 |

| I don’t mind spending the time and effort to purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness. | −0.009 | 0.541 | −0.144 | −0.060 |

| I would prefer for my family members to purchase organic foods based on environmental consciousness. | 0.149 | 0.764 | 0.073 | −0.087 |

| My loved ones expect me to purchase more organic food based on environmental consciousness for them. | 0.148 | 0.701 | 0.047 | −0.041 |

| I am willing to purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness without any condition. | 0.190 | 0.456 | −0.032 | 0.061 |

| I have enough knowledge of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. | −0.227 | 0.498 | −0.044 | 0.117 |

| Only people with higher incomes can afford organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. | 0.303 | −0.202 | 0.436 | −0.067 |

| Organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness is out of my budget. | −0.026 | −0.219 | 0.583 | −0.025 |

| Buying organic food based on environmental consciousness is very inconvenient. | −0.142 | 0.056 | 0.541 | 0.074 |

| Organic food is only available in limited stores/supermarkets/areas. | 0.115 | 0.127 | 0.553 | −0.043 |

| I do not have time to think about or study the meaning of organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness. | −0.166 | 0.007 | 0.423 | −0.016 |

| Without cooperation or understanding from family, it is difficult to purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness. | −0.106 | 0.044 | 0.483 | 0.121 |

| It is too expensive to purchase organic food based on environmental consciousness considering its meaning. | 0.028 | −0.069 | 0.764 | 0.030 |

| I think organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness is the first step to solving environmental issues. | 0.211 | 0.006 | 0.045 | 0.630 |

| My organic food purchasing based on environmental consciousness could make an impact on others’ purchasing behaviors. | −0.101 | 0.154 | 0.024 | 0.752 |

| By cooperating with others, organic food purchasing based on environmental consciousness can be a big leap in solving an environmental problem. | 0.221 | −0.111 | −0.016 | 0.696 |

| The probability that I can contribute to resolving environmental problems is not low. | 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.063 | 0.536 |

Note: We saved the factor score for each factor and used each factor as an observed variable in our analysis to reduce modification indices. All of these questionnaire items were measured by a five-point Likert scale where 1 = I don’t think so at all, 2 = I don’t think so, 3 = neither, 4 = I think so, and 5 = I think so very much. Attitude towards actual purchase (awareness and perception about organic food consumption based on environmental consciousness), social norm (moral norm, knowledge, and social pressure), perception of unaffordability and inconvenience (perception of the high monetary cost and unavailability of organic food), perceived effectiveness (environmental perception/environmental awareness).

References

- Deng, X. Factors Influencing Ethical Purchase Intentions of Consumers in China. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2013, 41, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E. Sustainable Lifestyles in an Urban Context: Towards a Holistic Understanding of Ethical Consumer Behaviours. Empirical Evidence from Catalonia, Spain. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doane, D. Taking Flight: The Rapid Growth of Ethical Consumerism; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2001; Available online: https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/dcca99d756562385f9_xtm6i6233.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2013. Available online: http://www5.agr.gc.ca/resources/prod/Internet-Internet/MISB-DGSIM/ATS-SEA/PDF/6473-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- The Inspection Certification System for Organic Products. 2015. Available online: http://www.maff.go.jp/e/jas/specific/pdf/organic_products_system_1501.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. Factors Influencing Indian Consumers’ Actual Buying Behaviour towards Organic Food Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Magnusson, M.; Sjoden, P. Determinants of Consumer Behavior Related To Organic Foods. Ambio 2005, 34, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International. Green Buying Behaviour: Global Online Survey. 2012. Available online: https://www.warc.com/content/paywall/article/euromonitor-strategy/green-buying-behaviour---global-online-survey-strategic-analysis/en-gb/96425 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Magnusson, M.K.; Arvola, A.; Koivisto Hursti, U.; Åberg, L.; Sjödén, P. Attitudes Towards Organic Foods Among Swedish Consumers. Br. Food J. 2001, 103, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L.; Tan, L.P. Exploring the Gap Between Consumers’ Green Rhetoric and Purchasing Behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, Y. Determinants of Environment-Conscious Behavior. Jpn. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 10, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory And Research; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, C.; Ferigan, J.E. A Two-Factor Model of Energy And Water Conservation; Edwards, J., Tindale, R.S., Heath, L., Posavac, E.J., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Voon, J.P.; Sing, K.; Agrawal, A. Determinants of Willingness to Purchase Organic Food: An Exploratory Study Using Structural Equation Modeling. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Azjen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossey, B.M.; Keegan, L.; Blaszko-Helming, M.A. Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sadbury, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose, Y. Two-Phase Decision Making Model of Environmental Conscious Behavior and Its Application for the Waste Reduction Behavior. Soc. Secur. Bull. 2014, 5, 81–91. Available online: https://www.kansai-u.ac.jp/Fc_ss/common/pdf/bulletin005_13.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Honkanen, P.; Verplanken, B.; Olsen, S.O. Ethical Values and Motives Driving Organic Food Choice. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Maclnnis, D.J. Consumer Behavior; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Thogersen, J. Consumer Decision-Making with Regard To Organic Food Products. In Traditional Food Production and Rural Sustainable Development: A European Challenge; de Noronha Vaz, T., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Ashgate: London, UK, 2009; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate the Determinants of Recycling Behaviour: A Case Study From Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H. A Study of Normative and Informtive Social Influences upon Individual Judgement. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lin, J.C.C. Acceptance of Blog Usage: The Roles of Technology Acceptance, Social Influence and Knowledge Sharing Motivation. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Pereira, M.C.; Cruz, L.; Sim, P.; Barata, E. Affect and the Adoption of Pro-Environmental Behaviour: A Structural Model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Choi, J.-G. Antecedents and Interrelationships of Three Types of Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Ohsako, M. Study of The Effect Of Political Measures On The Citizen Participation Rate In Recycling And On The Environmental Load Reduction. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, S9–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A.; Pearl, J. Eight Myths About Causality and Structural Equation Models. In Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research; Morgan, S., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically Concerned Consumers: Who Are They? J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.G. Psychological Types; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Notani, A.S. Perceptions of affordability: Their role in predicting purchase intent and purchase. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Holden, S.J.S. Understanding the Determinants of Environmentally Conscious Behavior. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, M.; Kahriman, M.; Çakir Biçer, N.; Seçkiner, S. Results from Türkiye: Which Factors Drive Consumers to Buy Organic Food? Foods 2024, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitner-Schobesberger, B.; Darnhofer, I.; Somsook, S.; Vogl, C.R. Consumer perceptions of organic foods in Bangkok, Thailand. Food Policy 2008, 33, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamet, A.; Nakayasu, A.; Bai, H. The Determinants of Organic Vegetable Purchasing in Jabodetabek Region, Indonesia. Foods 2016, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neal, P.W. Motivation of Health Behavior; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.-F.; Malesios, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Huang, W.; Tang, Y.; Man Li, R.Y.; Yue, X. Health-driven mechanism of organic food consumption: A structural equation modelling approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, N.; Tokunaga, S.; Nga, D.T.; Ho, V.; Thanh, T. Analysis of Energy-saving Behavior among University Students in Vietnam. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. B 2016, 5, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kuhling, J. Determinants of Pro-Environmental Consumption: The Role of Reference Groups and Routine Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACNielsen. Organic and Functional Foods Have Plenty of Room to Grow in U.S. 2005. Available online: https://progressivegrocer.com/organic-and-functional-foods-have-plenty-room-grow-us-acnielsen (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Chan, L.B. A Moral Basis for Recycling: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Nomura, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Yabe, M. Model of Chinese Household Kitchen Waste Separation Behavior: A Case Study In Beijing City. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).