Abstract

The tourism industry, which is exposed to a turbulent environment, is one of the sectors that are the most vulnerable to any change (such as political, economic, environmental, or social). This makes it necessary to study firm resilience in this industry in order to identify the factors that can enhance companies’ capacity for resilience in turbulent environments. Moreover, the strategies pursued by tourism companies to become more resilient and more competitive are closely related to tourism sustainability. Among the factors that can affect resilience, we analyze the roles of the degree of internationalization and network ties. Moreover, we explore the influence of resilience on the sustainable competitiveness of hotel firms. For this purpose, we propose a variance-based structural equation modeling analysis where resilience acts as a mediating variable between the degree of internationalization and sustainable competitiveness. Our results allow us to draw important theoretical implications, which shed light on a field of study that is currently much debated, and practical implications, which will help hotel entrepreneurs to make timely decisions in dynamic environments.

1. Introduction

The relationship between internationalization and competitiveness has been a topic of critical interest for decades. Many studies have focused their attention on trying to determine whether the decision to operate in other markets brings benefits to a firm, with mixed results being obtained. Some argue that competitiveness increases as a firm increases its level of internationalization [1,2,3], while others have found opposite results [4,5]. There are even papers that question whether there is a direct relationship between the two variables [6].

In the hotel industry, we can find the same debates on the relationship between internationalization and competitiveness [7,8]. However, recent studies do not advocate so much to determine the effect of internationalization, but to determine what other factors can drive a positive effect between the two [9]. In addition, it is still a challenge to understand the factors that encourage increasingly sustainable tourism development [10].

Given the highly dynamic nature of the hotel industry, resilience appears to be a key factor in remaining competitive and achieving sustainable development. Business resilience in an international context requires greater adaptability, increased resilience, and more concerted coordination of foreign operations [11]. Although the number of studies focusing on sustainable resilience has increased in recent years, the relationship between resilience and internationalization has not yet been widely explored [12]. Thus, there is a need for research in this direction, and the purpose of this paper is to find out whether resilience can have a mediating effect between the degree of internationalization undertaken by hotel companies and their achieved competitiveness, increasing sustainable development in the tourism industry.

Similarly, a company’s ability to obtain information about the sector and its environment through its relationships with associations and institutions has not been addressed in this context. Previous studies have analyzed the influence of cooperative agreements on tourism firms’ performance, and even on destination-level competitiveness [13,14,15]. However, less attention has been paid to the relationship between network ties and organizational resilience.

The contributions of this paper are summarized below. The structure of this paper is organized as follows: First, we combine the theory of organizational learning and the social network theory with hotel resilience in an international context. Second, we advance the concept of resilience by considering it not as an outcome, but as a process that may also condition other relationships that were previously studied in the literature. Finally, we examine the effect of network ties on the hotel industry.

The next section begins with a review of the literature and the formulation of various hypotheses. Then, in the Materials and Methods Section, the different variables included in the model and the technique used are explained. The results obtained are then presented and discussed. This paper ends with some final conclusions, the main limitations, and future lines of research.

2. Literature Review

In recent decades, the hotel industry has suffered major setbacks and has had a need to continuously adapt to new circumstances. This adaptability has been recognized in previous works as a necessary condition in this sector, contributing to the competitiveness of companies and their survival [16]. Furthermore, organizational resilience has been considered a tool to support sustainable development, providing novel insights into social and environmental adaptability to an ever-changing society [17]. Likewise, Souza et al. [18] described the need to develop corporate resilience, which will drive sustainability.

In this context, the term resilience, which was first developed in psychological and environmental research (e.g., see [19,20,21]), refers to the ability of organizations (and ultimately, entrepreneurs) to effectively adjust their activities, solve problems, and create strategies for new situations [22]. In ecology, it refers to the ability of an ecosystem to absorb disturbances while maintaining its functions [23,24]. From a psychological perspective, resilience is a trait or ability that allows people to cope with adversity and adapt positively to it [25]. From this perspective, Luthans [26] recommends viewing resilience as the dynamic ability to bounce back and cope effectively with change, adversity, or significant risk. From a strategic point of view, the environment plays a special role. Sustainability is considered very important because it can ensure the creation of a competitive advantage [27] that not only guarantees survival, but also growth. This is a key issue in the international context. If the environment changes, an organization must change and adapt to the new circumstances [28].

Subsequent applications of resilience have recognized the complex adaptive nature of systems. This recognition has led to a view of resilience that involves adapting and transforming systems through the emergence of new structures, such as policies, processes, and organizational culture, allowing organizations to continue operating despite challenges [29]. Organizational resilience can be seen as a process rather than an outcome per se [30]. As a process, resilience involves dealing effectively with adverse events not only after they occur, but also before and during them. Duchek [31] recognizes the dynamic nature of resilience and thus provides a foundation for studying the long-term development of organizational resilience.

The tourism industry is considered one of the sectors with the greatest capacity to adapt and recover from catastrophic or unexpected events [16]. In recent years, we have found many studies that have tried to relate this resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic [32,33,34]. However, few have attempted to link resilience and competitiveness in an international context. The research on resilience in this sector is scarce and recent [35], and only a few studies have dealt with tourism firms [36].

2.1. Internationalization and Sustainable Competitiveness in the Hotel Industry

Over decades, the relationship between internationalization and competitiveness has been extensively studied, and mixed results have been found. The decision to expand into another business involves many costs for a company to deal with, including cultural differences [37], resulting in risks and costs associated with the implementation of the strategy [38]. These significant costs may explain the negative relationship between international trade and competitiveness [39].

However, it is not only the costs, but also the benefits of this strategy that stand out. There are many theories that suggest that the advantage comes from achieving economies of scale, while the possibility comes from focusing on different markets [40]. Some authors have pointed out the positive consequences of different risk factors [41]. From a management perspective, international trade deals with the increase in or creation of certain resources resulting from the transfer of resources between different international organizations. The organizational learning theory begins from the resource perspective and proposes thinking about global resources and key resources as drivers of collaboration, learning, and knowledge development in an organization [42]. This theory can explain the real impact of international trade on sustainable competitiveness.

In view of this relationship, the hotel industry presents a number of characteristics that require more specific studies [39], including the intangible nature of the services offered and the simultaneous production of the services offered and their consumption. When a service firm expands overseas for the first time, it must invest significantly more than a manufacturing firm that usually begins its overseas expansion by exporting. Such an investment is likely to increase costs and thus reduce the competitiveness of these firms in the short term [43]. As a result, service firms are less likely to benefit from economies of scale when manufacturing firms expand internationally. Indeed, the competitiveness of hotel firms is expected to decline in the early stages of internationalization due to the initial investment required. Nevertheless, firms increase their competitiveness by accumulating market knowledge from higher levels of internationalization, which will have a sustainable effect over time [44].

In particular, initial investment and fixed costs can be spread over more than one source [39]. Having a presence in many countries allows companies to achieve economies of scale and take advantage of more business opportunities for suppliers, customers, and intermediaries, leading to an increased risk of “price discrimination, strategic cross-subsidies, and arbitrage” [45] (p. 8). More importantly, as the level of internationalization increases and the pressure to improve performance increases, organizational learning begins, enabling companies to adapt their international systems to the needs of global markets and restore positive performance, which helps to strengthen their internationalization position [46]. Previous studies in this industry have also found a positive relationship between the degree of internationalization adopted by the firm and greater and sustainable competitiveness [2,44]. Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis in this sense:

H1:

Hotel firms’ degree of internationalization positively influences sustainable competitiveness.

2.2. Organizational Resilience: Mediating Role

Internationalization is frequently described as a challenging process of organizational learning [9]. The process of internationalization means, among other things, that businesses acquire new knowledge, take risks, and interact with new environments; this leads to the improvement of many aspects of organizations and management [47]. Although recent studies have revealed a positive and significant association between the degree of internationalization and higher performance, other studies have shown that this relationship is more complex and requires the consideration of other variables that influence the dependence of one on the other [44].

Uncertainty and the need to adapt to unforeseen business-related changes increase when operating on an international scale [12]. These firms’ responses to adversity are likely to be more complex than when in a domestic environment, as conducting business across borders adds numerous levels of institutional and market uncertainty [48,49]. Developments at the international level provide essential learning and guidance for businesses to offset potential difficulties in this process and make them more resilient [50,51]. By being more proactive, organizations are alert to early warning signs and are more likely to have proven response and recovery plans [22].

Moreover, hotels can gain a competitive advantage through flexibility and adaptability to changes, becoming more competitive. Hotel firms must not only be ready to respond to change when it occurs, but also anticipate it in order to meet the challenges and maximize the opportunities [52]. Organizational resilience not only helps organizations survive, but also helps improve firms’ competitiveness [36,53]. In addition, authors such as Sobaih et al. [54] have analyzed the inherent relationship between organizational resilience and hotel performance as drivers of tourism sustainability, finding strong relationships across the board. Undoubtedly, these research topics are of recent interest and deserve further study. Furthermore, Cavaco and Machado [55] conducted an in-depth exploration of sustainable competitiveness based on resilience.

Some of the existing research relates these two dimensions. De Carvalho et al. [56] suggest that innovative companies have better financial performance and are better able to solve problems, i.e., they are more resilient. Prayag et al. [57] study the impact of planned and adaptive resilience on the financial performance of tourism businesses. In turn, Chowdhury et al. [58] provides empirical evidence of the relationship between adaptive resilience and post-disaster business performance. The latter authors argue that resilient organizations create the necessary resources and capability to make better decisions in an uncertain environment, thus improving performance. More recently, the works of Marco-Lajara et al. [36] and Melián-Alzola et al. [53] have confirmed the impact of organizational resilience on performance. Considering these arguments, the second hypothesis arises:

H2:

Hotel resilience mediates the influence of the degree of internationalization on sustainable competitiveness.

2.3. Network Ties: Moderating Role

According to the social network theory proposed by Barnes [59], firms can be part of relational structures or networks that connect them with other actors, such as institutions, individuals, or other organizations. Networks explain part of their success, as cooperation allows firms to solve problems more easily and effectively [60]. The contacts of networks allow them to identify opportunities or obtain resources, which are potential sources of competitive advantage [61]. Among tourism companies, Wilke et al. [14] found that hotel companies were the most likely to maintain some kind of agreement or partnership with other companies.

Connections between different actors can enable organizations to reach more customers or markets, including international ones [62]. Therefore, one would expect an internationalized hotel to increase its number of network ties. The more connections a company has, the more information, knowledge, influence, and power it controls [60].

Wilke et al. [14] found that cooperation with other firms in the tourism sector enhanced internal capabilities for innovation, absorption, and adaptation, generating competitive advantage and improving firm performance. These capabilities relate to the concept of resilience discussed above. Brown et al. [63] defines resilience in the hospitality sector as a dynamic capacity of firms to innovate, adapt, and overcome difficulties. Therefore, a firm’s membership in business networks can enhance its social capital, and thus, its resilience [63]. A high level of social capital can act as a buffer against crises, as social networks provide support to firms in difficult times [64].

Given that we have argued in the previous hypothesis that resilience mediates the relationship between the internationalization and sustainable competitiveness of hotel companies, it is possible that network ties have a certain moderating effect on the resilience of internationalized hotels. To this end, we suggest the following hypothesis for testing:

H3:

Hotel network ties positively moderate the internationalization–resilience relationship.

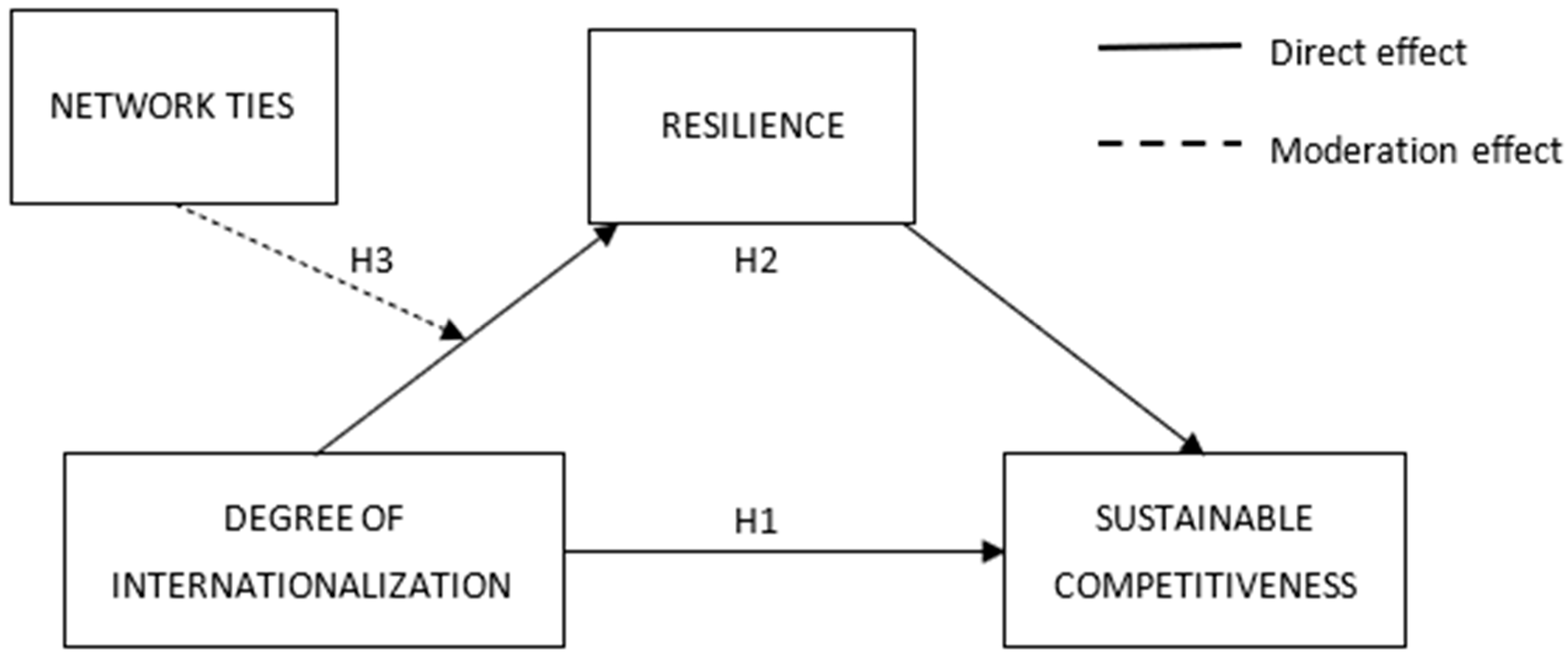

The different hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) and the proposed relationships (direct, mediation, and moderation) are shown in the below figure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample

The present study arises after the implementation of a research project aimed at consolidated research groups (AICO/2021) funded by the Generalitat Valenciana (Spain). The project focused on the study of the resilience of hotel companies in the Valencian Community (Spain) that were hit by the COVID-19 crisis. The Valencian Community was positioned in 2023 as the third destination country chosen by domestic tourists and was among the most chosen by non-resident tourists, consolidating its tourist position with more than 9.4 million travelers; this fact shows that there has been an improvement since the pre-pandemic situation in 2019 [65].

There were 842 hotels present in the Valencian Community in 2022 according to official INE data [65]. These hotels had a total of an estimated 50,947 rooms and employed almost 13,000 employees. More than 46% of these hotels would be located in the province of Alicante (392) compared to 38% located in the province of Valencia (320) and just over 15% in the province of Castellón (130).

The collection of information to test the hypotheses set out in this research model was carried out using a structured questionnaire sent by e-mail to the managers of the participating companies. The questionnaire was validated by means of a pre-test that was carried out on a group of experts in the field to verify that the questions were properly understood. The questionnaire was sent using the QualtricsXM software to all 842 hotels, of which 57 responses were received, representing a participation rate of 6.8%. The sample size is adequate according to the criteria of Hair et al. [66], who make recommendations on minimum sample size requirements for structural equation analyses. Specifically, these authors propose that for the case of the present model, in which the number of independent variables is 3, 53 observations would be required to achieve a statistical power of 80% with R2 values of at least 0.25 (with a 1% probability of error).

On average, the hotels in the sample have 517 establishments abroad. These hotels are in an average of 12 foreign countries. In addition, only 29 of the surveyed hotels belong to a business association, representing slightly more than 50% of the sample.

3.2. Measuring Variables

Most of the variables used in the questionnaire addressed to hotel managers came from Likert-type scales that were previously validated in the academic literature. The measures used for each of the variables in the research model are presented below.

Degree of Internationalization (DOI): The level of internationalization is evaluated by four indicators. The first is the number of international operations in the hotel industry, which is usually measured as the ratio of the number of foreign rooms to the total number of rooms [2,3]. The second is the number of foreign countries in which it operates [67]. Another common measure in hospitality industry research refers to the geographical distribution area completed by the company’s activities [44]. The third indicator is the number of hotels abroad [68]. Finally, the fourth indicator is the years of international experience that the company has.

Hotel resilience: We measured this variable with 11 items from Orchiston and Higham’s [69] hospitality organizational resilience scale, which was previously revised by Pathak and Joshi [70].

Sustainable hotel competitiveness: Following Fraj et al. [71] and Božič and Knežević Cvelbar [72], we asked the participants to evaluate relative sustainable competitiveness to its main competitors using an 8-point Likert scale. Four factors (Average Daily Rate—ADR; Revenue Per Room—RevPAR; Customer Satisfaction; and Employee Satisfaction) specifically represent challenges in the hotel industry, and the others refer to general competitiveness measures such as EBIT, ROI, ROS, and market share. These items were previously used for evaluations of the hotel industry [14].

Network ties: Previous studies have measured the propensity of hotel companies to network ties through the number of business associations of which a company is a member [61,73,74].

3.3. Analysis Technique

The partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) was applied as a statistical technique to look for linking data and theories. This methodology enables the representation, prediction, and testing of theoretical networks of relationships between unobserved variables (i.e., latent variables). This approach has been used to estimate causal models based on various theoretical models and empirical data [75]. In recent years, these techniques have been used in different studies in the hotel industry (e.g., see [76,77,78]) and with a reduced sample [43].

Indeed, there are several advantages associated with this analysis technique, which have been pointed out in several research studies. It is worth noting that it does not make specific demands on the distribution of sample data and does not require the observations to have predetermined independence [66]. It is a nonparametric statistical method, which does not require the presentation of a normal distribution of the data, although it requires that the data meet the minimum requirements to demonstrate that they are not excessively abnormal by means of kurtosis and skewness [66]. Another important advantage of the technique used is the possibility of performing complex model analyses, such as the one presented in this paper, which include both mediation and moderation relationships [66]. Furthermore, the choice of this method can also be associated with the type of explanatory study, which fits the context of the PLS-SEM. Also, the study population is small, and this technique can be used with smaller sample sizes (n = 57), so it fits well with the sample size requirements set for PLS [79]. The analysis was implemented using the SmartPLS software v4.2 [80].

4. Results

The results will be presented in two main parts. In the first part, the analysis of the measurement model was carried out, from which we tested the reliability and validity of each of the constructs used in our model. Following the recommendations of Hair et al. [66], this analysis of the measurement model first included the verification of the loadings of each item of the district constructs, which exceeded the critical value of 0.707 [81]. Then, the reliability of each construct or internal consistency was analyzed by checking the Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.8, as well as the rho_a and rho_c (see Table 1). Subsequently, the convergent validity of the constructs was checked by observing the AVE (whose values were all above 0.5, as can be seen in Table 1). To complete this first stage, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio Matrix (HTMT) was analyzed to check the discriminant reliability of our model (see Table 2) by following the strict criterion of values lower than 0.85 [82].

Table 1.

Reliability and validity of constructs.

Table 2.

Discriminant reliability of constructs. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio Matrix (HTMT).

In the second part of the presentation of the results, the structural model was analyzed to determine the capacity of our model to predict the objective constructs, as well as the relationships between them, so that we could test the hypotheses put forward in the theoretical framework. Table 3 shows the estimated path coefficients after bootstrapping, as well as the values of the coefficient of determination, R2, which shows the predictive power of our model. In this case, we focus on the value of our final variable (sustainable hotel competitiveness), which takes the value of 0.708, a value that exceeds the levels proposed in the study by Chin [83].

Table 3.

Results of structural model.

The results shown in the table above allow us to support only two of the three hypotheses put forward in our theoretical model. Firstly, it can be observed that the relationship between the degree of internationalization and sustainable hotel competitiveness is positive and significant (Hypothesis 1 is supported). Secondly, the most important relationship that emerged from the analysis is the crucial effect of the international character of hotels on their resilience and the subsequent positive influence of this resilience on sustainable hotel competitiveness. This allows us to affirm the existence of a partial mediation relationship between the degree of internationalization of hotels and resilience-based competitiveness (see the positive and statistically significant value of the mediation relationship in Table 3). The second hypothesis is also supported. The total effect of the degree of internationalization on sustainable competitiveness rises to 0.281 with a p-value of 0.000.

Finally, the non-significant result of the moderation effect of the associations in the relationship between internationalization and resilience is surprising. Indeed, this moderation cannot be supported, which leads us to reject Hypothesis 3. In our model, network ties do not exert any influence on the internationalization–resilience relationship, i.e., these associations do not drive international hotels to develop higher resilience capacities.

5. Discussion

As the results show, the absence of a stronger and more significant relationship between the DOI and the sustainable hotel competitiveness of the tourism firms analyzed can be explained by the numerous costs mentioned by Capar and Kotabe [39] at an early stage. Moreover, given that these are service firms, they are less likely to benefit from economies of scale than manufacturing firms that have expanded internationally. However, although the significance is not very high, we can affirm that increasing the DOI increases the competitiveness of the hotels studied, which may be due to the accumulation of market knowledge, as mentioned by Rienda et al. [44]. Recently, authors such as Babgohari et al. [84] have also found several barriers to SME internationalization practices from a sustainability and resilience approach.

Moreover, the results of the present research allow us to highlight the crucial effect that resilience capacity exerts between internationalization and sustainable hotel competitiveness. Such findings are in line with the extensive assertions of authors who have recently pointed out the need for hotel managers to enhance their resilience capacity today [36,54]. Given this relationship and the differences arising from hotels’ sustainable competitive resilience, this may be an explanatory factor, but there are many other strategic factors that complement and explain it more broadly. This opens up different and interesting research directions in this field.

This research allows us to go a step further and show the key effect that this capacity has for international hospitality companies that seek to obtain higher performance and cannot achieve it directly [44]. Such international hotels should be concerned with enhancing their resilience in the different markets in which they operate, because only then will their performance be sufficiently altered. In line with the studies by Martins et al. [50] and Puhr and Mullner [51], the international development of firms provides them with essential learning to compensate for the difficulties of the process and allows them to become more resilient.

One of the results obtained in the present research work differs from what was put forward in the theoretical framework, i.e., the rejection of Hypothesis 3 that supported a positive moderation relationship between associations and the relationship between the DOI and resilience. This result could have its justification in the variable employed. Perhaps the number of business associations of which a company is a member does not represent the benefits of cooperation agreements carried out by hotels. In addition, the challenges faced by international hotels may not be solved with the network ties they have locally, and they must develop other competencies and skills to boost their resilience. Therefore, although we cannot affirm in this study that hotel network ties have a positive effect and increase resilience, we consider that cooperation is a key variable, and further studies are needed to help understand this result.

6. Conclusions

Resilience not only plays an essential role for hotels that compete in the regional or national territory, but also for those that are internationalized. The international development of hotels boosts their learning and resilience capacity, leading to higher performance or sustainable competitiveness, which promotes tourism sustainability. Although we were not able to demonstrate in our work that cooperation has a positive influence on resilience, it is undoubtedly a way for internationalized companies to improve their adaptive capacity, and more studies are needed to incorporate these ideas.

The main conclusions of this research allow us to draw different implications both from theoretical and practical points of view. First of all, this research has allowed us to deepen the already addressed relationship between the degree of internationalization of hotels and their sustainable hotel competitiveness by offering a very relevant novelty, namely the mediating role of the resilience capacity of hotels. This, in turn, serves to encourage directors and managers of international hotels to develop this resilience capacity in the current times of uncertainty, as it will allow them to boost their international performance.

The present study is not without limitations, which allows us to propose different lines of future research. Firstly, one of the main limitations of our paper is that the results may not be generalizable as this study focuses on a specific geographical area with a small sample. However, given the tourist importance of this area, previous studies (e.g., see [85,86]) have focused on tourist enclaves in the Valencian Community, such as Benidorm and Alicante, although with a larger sample of hotel firms. Future research may extend the scope of analysis to other geographical areas in order to extrapolate our results. Secondly, the lack of statistical significance in the results regarding the moderating effect of network linkages indicates that a more comprehensive or nuanced understanding of this variable is required. It might be interesting for future work to incorporate new qualitative dimensions of different network affiliations (e.g., the degree of trust, formal vs. informal, and local vs. global) and make distinctions between them. This could facilitate the elucidation of the circumstances under which network connections enhance both resilience and sustainable competitiveness. In line with this idea, it would be interesting to incorporate new variables into the model in order to provide a more holistic understanding of the strategic environment in which international hotels operate, such as the interaction between technology adoption, sustainability practices, internationalization, resilience, and competitiveness. Finally, an examination of hotel industry operations in relation to different challenges and prospects in alternative tourism subsectors or even industries in general may shed light on the unique characteristics of this sector. Future comparative analyses of this nature could provide insights into the uniqueness of this sector or the broader applicability of the observed relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and L.R.-F.; methodology, L.R.-F.; software, L.R.-F.; validation, R.A., L.R. and L.R.-F.; formal analysis, R.A.; investigation, L.R.; resources, R.A.; data curation, L.R.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; writing—review and editing, R.A., L.R. and L.R.-F.; visualization, R.A.; supervision, L.R.; project administration, L.R.; funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital de la Generalitat Valenciana in the framework of the Program for the promotion of scientific research, technological development and innovation in the Comunitat Valenciana, in the category of consolidatable research groups (Grant number AICO/2021/192).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants were fully informed that anonymity was guaranteed, why the research was being conducted, how their data would be used, and that there would be no associated risks. Approval for the study was not required in accordance with local/national legislation.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bausch, A.; Krist, M. The effect of context-related moderators on the internationalization-performance relationship: Evidence from meta-analysis. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 2007, 47, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Upneja, A.; Özdemir, Ö.; Sun, K.-A. A synergy effect of internationalization and firm size on performance. US hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Ramón-Rodriguez, A.B.; Such-Devesa, M.J.; Driha, O. The inverted-U relationship between the degree of internationalization and the performance: The case of Spanish hotel chains. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerzen, A.; Beamish, P.W. Geographic scope and multinational enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, K. Multinationality, configuration, and performance: A study of MNEs in the US drug and pharmaceutical industry. J. Int. Manag. 1995, 1, 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hennart, J.F. The theoretical rationale for a multinationality-performance relationship. Manag. Int. Rev. 2007, 47, 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienda, L.; Andreu, R. The role of family firms heterogeneity on the internationalisation and performance relationship. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2021, 11, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lee, S. The Effect of Internationalization on Firm Performance: A Moderating Role of Heterogeneity in TMTs’ Nationality. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Josiassen, A.; Oh, H. Internationalization and hotel performance: The missing pieces. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 572–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.V.; Tran, G.N.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, C.V. Factors affecting sustainable tourism development in Ba Ria-Vung tau, Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T.; Heikkilä, M.; Nummela, N. Business model innovation for resilient international growth. Small Enterp. Res. 2022, 29, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, T.; Atkova, I.; Gabrielsson, P. Business modeling under adversity: Resilience in international firms. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2023, 17, 802–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.; Aria, M. Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The case of tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, E.P.; Costa, B.K.; Freire, O.B.D.L.; Ferreira, M.P. Interorganizational cooperation in tourist destination: Building performance in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.; Franco, M. Interorganizational Networks for Competitiveness in Tourism. Tour. Anal. 2023, 28, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A. Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Alves, M.; Macini, N.; Cezarino, L.O.; Liboni, L.B. Resilience for sustainability as an eco-capability. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 9, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, W.E. Resilience: Concepts and measures. In Resilience in Mediterranean-Type Ecosystems. Tasks for Vegetation Science; Dell, B., Hopkins, A.J.M., Lamont, B.B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 16, pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, E.E. Resilience in development. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.B. Toward an understanding of resilience: A critical review of definitions and models. In Resilience and Development; Glantz, M.D., Johnson, J.L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 17–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Crisis strategic planning for SMEs: Finding the silver lining. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5619–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Deimler, M.S. Strategies for winning in the current and post-recession environment. Strategy Leadersh. 2009, 37, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J. Disciplines of organizational resilience: Contributions, critiques, and future research avenues. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 879–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Kehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Time for Reset? COVID-19 and Tourism Resilience. Tour. Rev. Int. 2020, 24, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A. Come and gone! Psychological resilience and organizational resilience in tourism industry post COVID-19 pandemic: The role of life satisfaction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Prayag, G.; Amore, A. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M.; Ruiz-Fernández, L.; Poveda-Pareja, E.; Sánchez-García, E. Rural hotel resilience during COVID-19: The crucial role of CSR. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture´s Consequences. International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ruigrok, W.; Wagner, H. Internationalization and performance: An organizational learning perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 2003, 43, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Capar, N.; Kotabe, M. The relationship between international diversification and performance in service firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, R. International corporations: The industrial economics of foreign investment. Economica 1971, 38, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, B. Geographic scope of operations by multinational companies: An exploratory study of regional and global strategies. Eur. Manag. J. 2004, 22, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddewyn, J.J.; Halbrich, M.B.; Perry, A.C. Service multinationals: Conceptualization, measurement and theory. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1986, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienda, L.; Claver, E.; Andreu, R. Family involvement, internationalisation and performance: An empirical study of the Spanish hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, F.; Kundu, S.; Hsu, C.C. A three-stage theory of international expansion: The link between multinationality and performance in the service sector. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Josiassen, A.; Ratchford, B.T.; Pestana Barros, C. Internationalization and performance of retail firms: A bayesian dynamic model. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R.; Alegre, J. Organizational learning capability and job satisfaction: An empirical assessment in the ceramic tile industry. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Strange, R.; Cooke, F.L. Research on international business: The new realities. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. International entrepreneurship in the post Covid world. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Farinha, L.; Ferreira, J.J. Analysing stimuli and barriers, failure and resilience in companies’ internationalization: A systematic and bibliometric review. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2022, 32, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhr, H.; Müllner, J. Foreign to all but fluent in many: The effect of multinationality on shock resilience. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibay, V.; Miller, J.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Egbelakin, T.; Seville, E.; Wilkinson, S. Business resilience: A study of Auckland hospitality sector. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-Alzola, L.; Fernández-Monroy, M.; Hidalgo-Peñate, M. Hotels in contexts of uncertainty: Measuring organisational resilience. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.; Hasanein, A.M.; Abdelaziz, A.S. Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaco, N.M.; Machado, V.C. Sustainable competitiveness based on resilience and innovation—An alternative approach. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2015, 10, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, A.O.; Ribeiro, I.; Cirani, C.B.S.; Cintra, R.F. Organizational resilience: A comparative study between innovative and non-innovative companies based on the financial performance analysis. Int. J. Innov. 2016, 4, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Chowdhury, M.; Spector, S.; Orchiston, C. Organizational resilience and financial performance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Prayag, G.; Orchiston, C.; Spector, S. Postdisaster social capital, adaptive resilience and business performance of tourism organizations in Christchurch, New Zealand. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1209–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.A. Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viren, P.P.; Vogt, C.A.; Kline, C.; Rummel, A.M.; Tsao, J. Social network participation and coverage by tourism industry sector. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A.; Smith, K.A. Interfirm Alliances in the Small Business: The Role of Social Networks. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2002, 40, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, B.; Röhrer, N.; Fuchs, M.; Pilz, M. Cooperation Between Learning Venues and its Limits: The Hotel Industry in Cancún (Mexico). Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 8, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.A.; Orchiston, C.; Rovins, J.E.; Feldmann-Jensen, S.; Johnston, D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, D.C.; Hall, M.; Stoeckl, N. The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: Reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). Coyuntura Turística Hotelera (EOH/IPH/IRSH). Diciembre 2023 y año 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/CTH1223.htm (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tallman, S.; Li, J. Effects of international diversity and product diversity on performance of multinational firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. Determining factors in the internationalization of hotel industry: An analysis based on export performance. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchiston, C.; Higham, J.E.S. Knowledge management and tourism recovery (de) marketing: The Christchurch earthquakes 2010–2011. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Joshi, G. Impact of psychological capital and life satisfaction on organizational resilience during COVID-19: Indian tourism insights. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2398–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božič, V.; Knežević Cvelbar, L. Resources and capabilities driving performance in the hotel industry. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 22, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostgaard, T.A.; Birley, S. Personal Networks and Firm Competitive Strategy. A Strategic or Coincidental Match? J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, A. Networks and Entrepreneurship. An Analysis of Social Relations, Occupational Background, and Use of Contacts during the Establishment Process. Scand. J. Manag. 1995, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Aykol, B. Dynamic capabilities driving an eco-based advantage and performance in global hotel chains: The moderating effect of international strategy. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Moliner, J.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertursa-Ortega, E.M. How do dynamic capabilities explain hotel performance? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, L.; Rienda, L.; Andreu, R. The U-Shape Influence of Family Involvement in Hotel Chain: Examining Dynamic Capabilities in PLS-SEM. In State of the Art in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Methodological Extensions and Applications in the Social Sciences and Beyond; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 4. Monheim am Rhein: SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Babgohari, A.Z.; Esmaelnezhad, D.; Taghizadeh-Yazdi, M. Prioritising SMEs Internationalisation Practices Considering Their Various Interrelating Barriers: A Sustainability and Resiliency Approach. In Decision-Making in International Entrepreneurship: Unveiling Cognitive Implications Towards Entrepreneurial Internationalisation; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023; pp. 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Baquero, A. Is customer satisfaction achieved only with good hotel facilities? A moderated mediation model. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorin, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D. Environmental Strategies and Their Impact on Hotel Performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).