Abstract

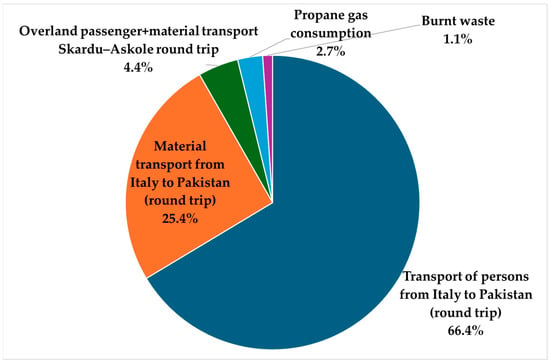

Often considered the most pristine natural areas, mountains are the third most important tourist destination in the world after coasts and islands, contributing significantly to the tourism sector (15–20%). Tourism is economically important for many mountain communities and is among the key drivers of economic growth in mountain regions worldwide. However, these high-altitude places are under increasing pressure from activities such as expeditions and trekking, which can contribute to the degradation of mountain ecosystems. In this study, we focused on the Italian expedition to K2 in July 2024, which celebrated the 70th anniversary of the first ascent in 1954. In particular, we assessed its environmental impact by estimating the expedition’s carbon footprint. We also discussed the different impact compared to the previous Italian expeditions. Overall, the 2024 Italian expedition to K2 had a carbon footprint of 27,654 kg CO2-eq, or 1383 kg CO2-eq per team member that flew from Italy. Air transport (i.e., the flight from Italy to Pakistan via Islamabad) was the largest source of emissions (91.7%, divided into 66.4% for passengers and 25.4% for cargo). Waste incineration was the smallest contributor (1.1%). Instead of using traditional diesel generators, the 2024 expedition used photovoltaic panels to generate electricity, eliminating further local greenhouse gas emissions. At the carbon credit price of 61.30 USD/ton of CO2 or 57.02 EUR/ton of CO2, offsetting the expedition’s emissions would cost 1695 USD or EUR 1577. This approach seems feasible and effective for mitigating the environmental impact of expeditions such as the one performed in 2024 by Italians.

1. Introduction

Mountain regions cover about a quarter of the Earth’s surface and host exceptionally varied and delicate ecosystems [1]. Often considered the Planet’s most pristine natural reserves, mountains serve as critical sources of fresh water, glaciers, and biodiversity. Mountains rank among the top global tourism destinations, following coasts and islands, and contribute approximately 15–20% to the global tourism sector [2]. Tourism plays an economically important role for many mountain communities and is among the key drivers of economic growth in mountain regions [1]. However, these high-altitude places are facing increasing pressure from activities such as expeditions, trekking, and transhumance practices, which have contributed to the degradation of mountain ecosystems [3]. In less than a century, mountaineering has evolved from an activity with only a handful of participants to a major tourist attraction, drawing thousands of visitors to high-altitude [4]. For example, as reported by the Government of Nepal Ministry of Culture [5], in 2022, Nepal welcomed 614,869 tourists (+307.3% respect to 2021), with 64.7% visiting for holidays and leisure. Adventure activities, including trekking and mountaineering, accounted for 10.0% of visitors, while 12.9% arrived for pilgrimage, and the remaining 12.4% came for various other purposes. Additionally, international flight arrivals increased three times in 2022 compared to 2021 [5]. Similarly, according to the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation report [6] in 2022 a total of 912,587 domestic tourists and 12,140 international tourists traveled to the Gilgit-Baltistan region. However, there is a lack of comprehensive data from the Tourism Department of Pakistan regarding the specific activities of these visitors.

Unfortunately, this surge in expeditions and related tourism has left a considerable environmental impact. Practices such as improper waste disposal, deforestation for firewood, and illegal hunting have severely damaged these fragile ecosystems, threatening biodiversity and contributing to carbon footprint and the degradation of the natural landscape [7]. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions due to air travel, helicopter transport, and logistical support for expeditions exacerbate the environmental impact, contributing to global warming and altering the safety of mountaineering by increasing the risk of rockfalls and avalanches due to shrinking glaciers. Tourism in general contributes approximately 8% of global carbon emissions [8], with transport being the largest contributor, responsible for 5% of all human-made greenhouse gas emissions [9]. Furthermore, gases such as CH4 and CO2 can be emitted from unattended waste, and the use of fossil fuels during such expeditions adds to the overall GHG levels, contributing to global warming, which in turn accelerates the glaciers’ melting [7].

Many mountaineers, primarily but not exclusively from the Western world, travel long distances to reach the fourteen 8000 m peaks located in the Himalayas and Karakoram ranges across Pakistan, Nepal, and Tibet. They travel thousands of kilometers and, due to time constraints, they often rely on air travel rather than trekking or overland transport. The climate impact of aviation sector is substantial. Although aviation is responsible for only 2.4% of the world’s annual CO2 emissions, it has contributed around 4% to man-made global warming [10]. Moreover, black carbon emissions significantly impact both human health and the environment [11].

Furthermore, tourist areas also face pollution issues due to improper waste disposal by visitors, which leads to environmental damage and can impact local climate patterns [12]. Kuniyal [7] highlighted that, in many cases, these activities result in waste accumulation, including non-biodegradable materials such as plastics and oxygen canisters, which are often abandoned at extreme altitudes due to the logistical challenges of retrieval. Human waste management is another critical issue, as waste left on mountains does not decompose in sub-zero conditions, posing environmental and health risks by contaminating snow and water sources [13]. In high-traffic adventure tourism areas such as Gilgit, Hunza, and the Baltoro Glacier (Pakistan), the need for recycling and waste management facilities has become urgent [7]. A case study of an expedition to the Pindari Valley in the Indian Himalayas revealed that about 60% of the non-biodegradable waste problem could be solved by reuse and recycling (39% and 21%, respectively) [7].

Within this context, in this paper, we focus on the July 2024 expedition to K2 (Pakistan), which celebrated the 70th anniversary from the first ascent performed in 1954 by a group of Italian climbers. In particular, we assess the environmental impact of the expedition carried out in July 2024 by estimating its carbon footprint. Moreover, we discuss this impact by comparing it with the one given by the team attending the 1954 K2 expedition. In this way, it is possible to discuss whether climbing and mountaineering are or not sustainable activities and whether the people practicing these sports are aware of their impacts on the environment.

In 1954, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, with the fundamental contribution of Walter Bonatti and Amir Mahdi and supported by a team of exceptional mountaineers led by Prof. Ardito Desio, made the first ascent of K2. The expedition was supported by the Italian Alpine Club (CAI). The 1954 expedition to K2 consisted of 30 members, 13 Italian mountaineers, 10 Hunza (Pakistani) mountaineers, five researchers (including Ardito Desio, the expedition leader), a government observer, and a Pakistani topographer.

Half a century later, the Project “K2 2004 Fifty Years Later” organized an expedition to K2, which took place between May and August 2004. It consisted of a team of 33 valuable and professional mountaineers, mountain guides, members of the Mountain Rescue Service, CAI academics, and elite mountaineering associations. The coordination was entrusted to the EvK2CNR Association. The 2004 expedition was not only of a sporting nature. The mountaineers were joined by technicians and scientists: 49 experts worked on nine projects under the coordination of the National Institute for Scientific and Technological Mountain Research (INRM).

In 2014, the entrusted association EVK2CNR organized the first Pakistani expedition to successfully reach the summit of K2, the mountain that symbolizes Italian–Pakistani friendship.

In summer 2024, 70 years later the first K2 ascent, the platinum anniversary was celebrated with the first Italian and Pakistani women’s expedition to K2 along the Abruzzi Spur. Italian mountaineers Anna Torretta, Federica Mingolla, Cristina Piolini, and Silvia Loreggian undertook the expedition with their Pakistani companions Samina Baig, Amina Bano, Nadeema Sahar, and Samana Rahim. The Abruzzi Spur is the most popular route on K2, with 75% of climbers attempting this pass, which is located on the Pakistani side of the mountain. This route was named after Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of Abruzzi, who first attempted to cross it in 1909. The 2024 expedition was promoted and carried out by the CAI with the support of the entrusted association EVK2CNR. The expedition team flew from Italy to Islamabad (Pakistan) on 16 June 2024, and then took an internal flight to Skardu, from where they arrived in Askole by jeep. From here the real trek began, with the first stop at Jula, then Paju, Urdukas, Gore 2, Concordia, and finally Base Camp. It was here that the personnel and service tents were installed and the starting point for the attempts to reach the summit of K2 was located. The actual mountaineering expedition lasted from 27 June to 1 August (36 days). The expedition team returned to Italy on 8 August 2024 (54 days).

2. Study Area

Situated in South Asia, Pakistan shares its borders with India (east), Afghanistan (west), Iran (southwest), and China (northeast). The country is geographically divided into four provinces (i.e., Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh), two autonomous territories (i.e., Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan), as well as a federal territory known as the Capital Territory of Islamabad.

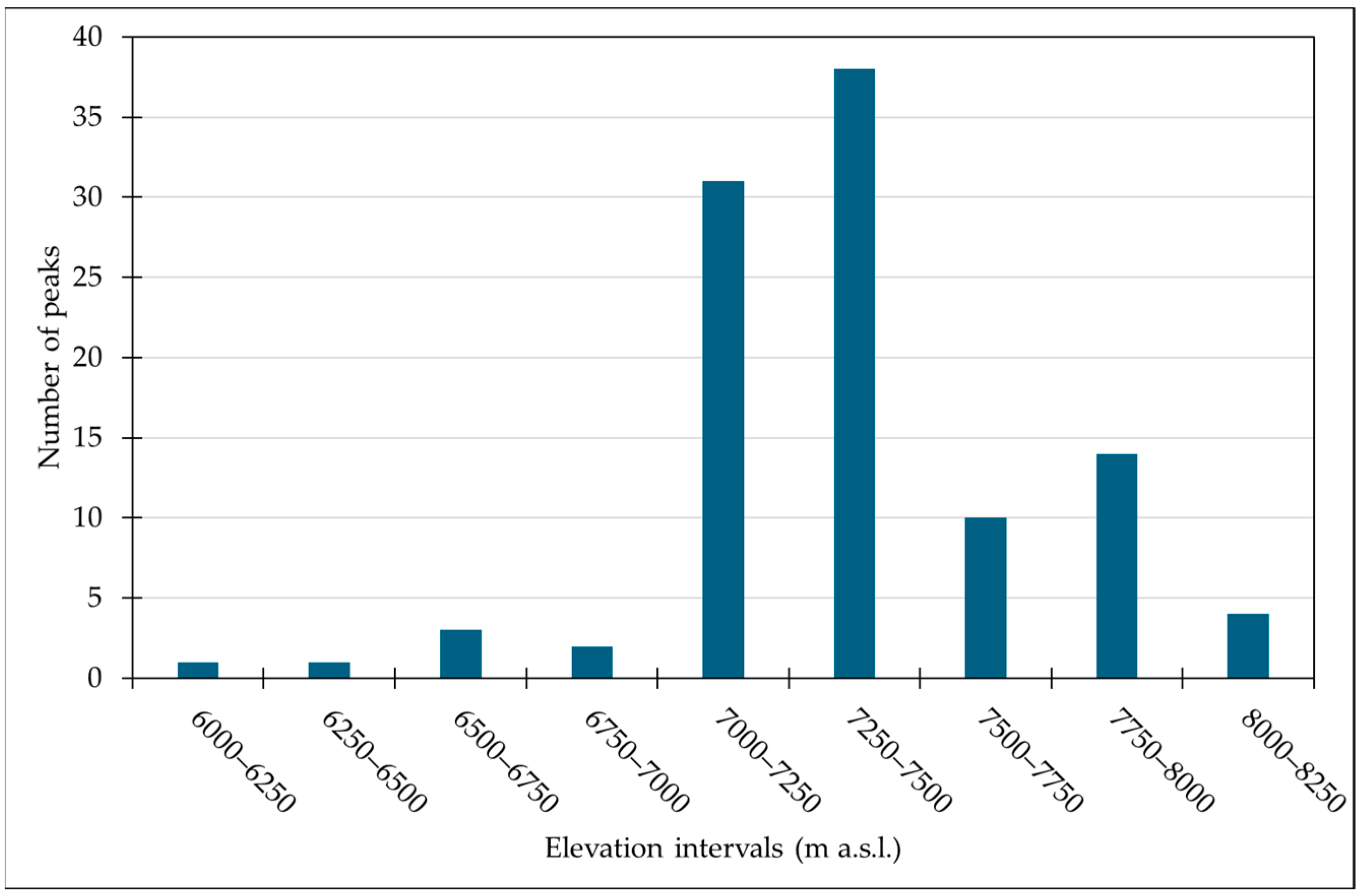

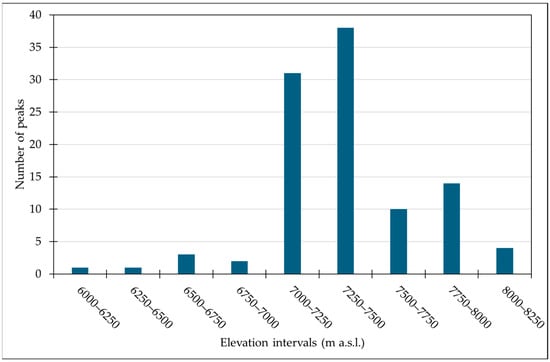

Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, is famous for being a transient tourist destination, as all foreign and domestic tourists traveling to the mountainous areas of the north pass through the city. In fact, Pakistan is the only country in the world where three famous mountain ranges converge: the Himalayas, the Karakoram, and the Hindu Kush. Pakistan, and particularly its northernmost region, Gilgit-Baltistan, has long been known to mountaineers as “the world’s best kept secret”. This highly mountainous region is home to some of the Planet’s longest glaciers (e.g., Baltoro [14]) and highest peaks [15], including the world’s second highest, K2 (8611 m a.s.l.). As reported by the Ministry of Interior of Pakistan, in Gilgit-Baltistan there are 107 peaks ranging from 6150 m a.s.l. of Skyang Kangri—W to 8611 m a.s.l. of K2 (Figure 1). Since the 1970s, thanks to the Karakoram Highway, climbers have attempted to reach the summit of five of the world’s fourteen eight-thousanders every year. The Ministry of Interior of Pakistan also makes available the list of treks (16 in total).

Figure 1.

The frequency distribution of peaks in Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan) sorted in elevation intervals.

As reported by [6], in 1970, the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC) was established to achieve the following:

- (i)

- Promote tourism development in Pakistan;

- (ii)

- Develop tourism infrastructure throughout the country;

- (iii)

- Promote Pakistani international and domestic tourism;

- (iv)

- Encourage the private market to become more active in helping to develop tourism;

- (v)

- Provide tourism services and ground handling activities.

The last decade has seen a continuous increase in international visitors in Pakistan. In 2013, there were 924,000 international arrivals and by 2019, the number had crossed 3.58 million. As reported on the webpage of Tourism, Sports, Culture, Archaeology & Museums Department of the Government of Gilgit-Baltistan (https://visitgilgitbaltistan.gov.pk/pages/tourist-inflow, accessed on 20 November 2024), 46% of the foreign tourists visit Gilgit-Baltistan.

3. Methods

According to [16], the carbon footprint can be defined as the amount of greenhouse gases expressed in CO2 equivalents (CO2-eq), emitted directly and indirectly into the atmosphere. It can be estimated at the level of an individual, an organization, a product, or an event.

To define how much a high-altitude mountaineering expedition, especially in extra-alpine areas, can impact the environment and to take possible mitigation measures, a detailed analysis of the CO2-eq emissions generated is essential.

For the 70th anniversary of the Italian expedition to K2 in July 2024, the carbon footprint was calculated considering the following: (i) the travel of the entire team from Italy to Pakistan round trip (20 people), (ii) the transport of material (2100 kg from Italy to Pakistan and 600 kg from Pakistan to Italy), (iii) the consumption of propane gas during the ascent (25 propane gas bottles of 10 kg), and (iv) the burning of waste (300 kg).

We estimated the CO2-eq emissions associated with mobility (Emobility) by summing the emissions that we derived for the different types of motorized transport. To achieve this aim, we took into account the emission factors (EFs, kg CO2-eq/km traveled) of each type of motorized transport and the distances traveled (D, km):

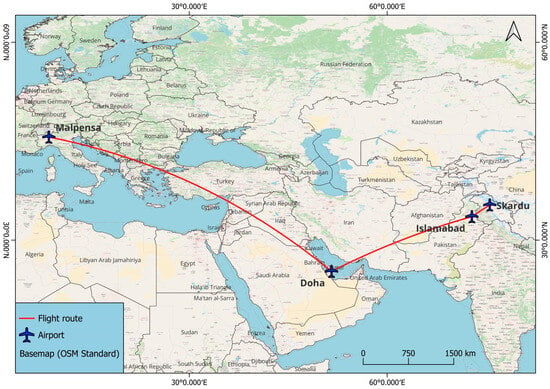

For air transport, estimates for personnel were based on data from the ICAO platform (https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Carbonoffset/Pages/default.aspx, accessed on 20 November 2024) and for equipment on data from the WebCargo platform (https://www.webcargo.co/resources/freight-co2-emissions-calculator/, accessed on 20 November 2024). Even though the ICAO platform makes a freighter calculator available as well, we preferred to not use this tool as the estimates do not seem completely reliable. As reported on the website, ICAO has provided a methodology (ICAO Carbon Emissions Calculator, ICEC) to quantify greenhouse gas emissions from aviation. The approach uses publicly available industry data to take into account several aspects such as aircraft type, route-specific data, passenger load factors, and cargo carried. The calculator of WebCargo provides values that are defined as tank-to-wheels GHG emissions in kilograms of CO2 equivalent. For personnel, we considered Malpensa Airport (Italy) as the departure location, Doha (Qatar) and Islamabad (Pakistan) as intermediate destinations, and Skardu (Pakistan) as the final destination (Figure 2). In addition, we used a round trip rather than a one-way trip in order to consider the full emissions for both the travels. For the freighter, we considered a direct flight from Malpensa Airport (Italy) to Islamabad (Pakistan) and another one from Islamabad (Pakistan) to Skardu (Pakistan). As the Islamabad–Skardu route was not available on the WebCargo website, we chose two other airports with similar distances.

Figure 2.

The flight path from Milan Malpensa Airport in Italy to Qatar Doha Airport and then Islamabad International Airport in Pakistan, followed by a domestic flight from Islamabad to Skardu Airport in Gilgit Baltistan.

Although there are direct flights from Rome Fiumicino Airport to Delhi Airport, which would have reduced carbon emissions, Milan Malpensa was chosen as the departure airport for this expedition because it was closer to the homes of most of the expedition members. Using Malpensa reduced the travel time and emissions associated with transport within Italy. In addition, Islamabad is the main entry point for climbers heading to K2 due to its proximity to the Karakoram range and its established infrastructure to connect with Northern Pakistan.

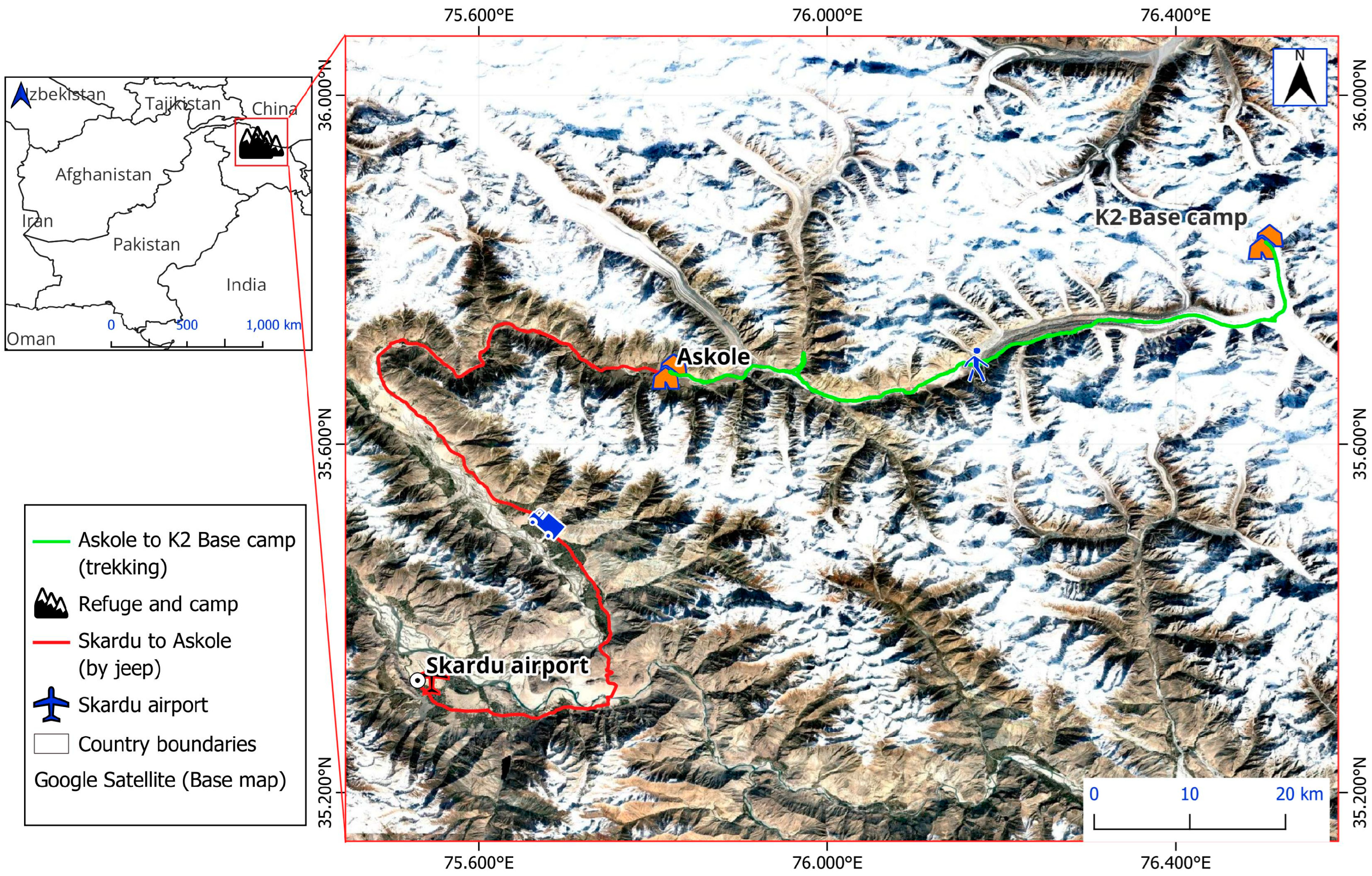

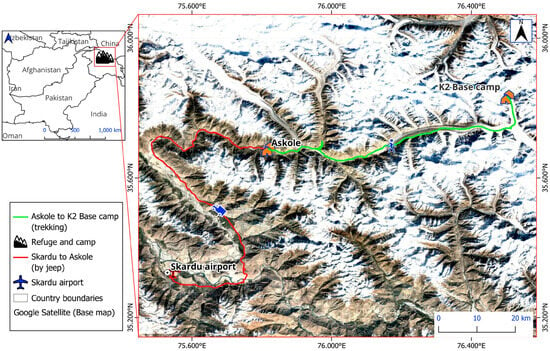

After arrival in Skardu (Pakistan), the transfer to Askole (starting point of the trek to the K2 base camp) was made by motor vehicles covering approximately 126 km (Figure 3) whose emissions depend on the type of vehicle and fuel consumption. The transport of people and materials from Skardu to Askole was based on the use of 12 jeeps, and the return trip was based on the use of 10 jeeps (with a fuel consumption of about 1 L per 6 km). The emission factor for diesel is 265 g CO2/L [17].

Figure 3.

The travel route from Skardu Airport to Askole by jeep (shown in red), and the onward trekking route from Askole to K2 Base Camp (shown in green).

Finally, the last part of the trip is a trek from Askole to the K2 base camp, about 90 km on foot.

Instead of using traditional diesel generators during the 2024 expedition, 20 photovoltaic panels (each with a capacity of 450 W and dimensions of 200 × 120 cm) were used to generate electricity, eliminating local greenhouse gas emissions. The impact of transport of solar panels from Italy was included in the emissions from the transport of the material. Only propane gas was burned for cooking. As reported by ISPRA in a 2003 report (https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/contentfiles/00003900/3906-rapporti-03-28.pdf/, accessed on 20 November 2024), LPG is a mixture of propane and butane in varying proportions, and therefore the emission factor can range from a minimum of 63 to 66 kg CO2/MJ. Therefore, we considered the emission factor for LPG reported by [18], which is 3.03 kg CO2/kg.

With regard to waste, we specifically considered waste generated by typical high-altitude expedition activities, i.e., only waste that could be systematically collected and subsequently incinerated as part of the expedition’s waste management process. The waste generated includes, for example, food waste (e.g., leftovers and expired products), food and drink packaging (e.g., plastic wrapping, cans, and bottles), damaged or discarded clothing and technical equipment (e.g., torn jackets and broken crampons), packaging of medicines and other medical supplies, disposable hygiene products (e.g., handkerchiefs and wet wipes), and materials or parts of tents discarded due to wear and tear or damage. The waste was first sorted to separate the metals from the rest, which was then incinerated in the Askole incinerator (approximately 300 kg in total). Following [19], we considered an emission factor of 1 kg CO2/kg of burnt waste.

This methodology does not take into account the emissions caused by overnight stays during the various stages of the journey to Askole (such as electricity consumption and food), since the expedition members would have, for example, eaten and used electricity anyway, even if they had stayed in Italy.

4. Results and Discussion

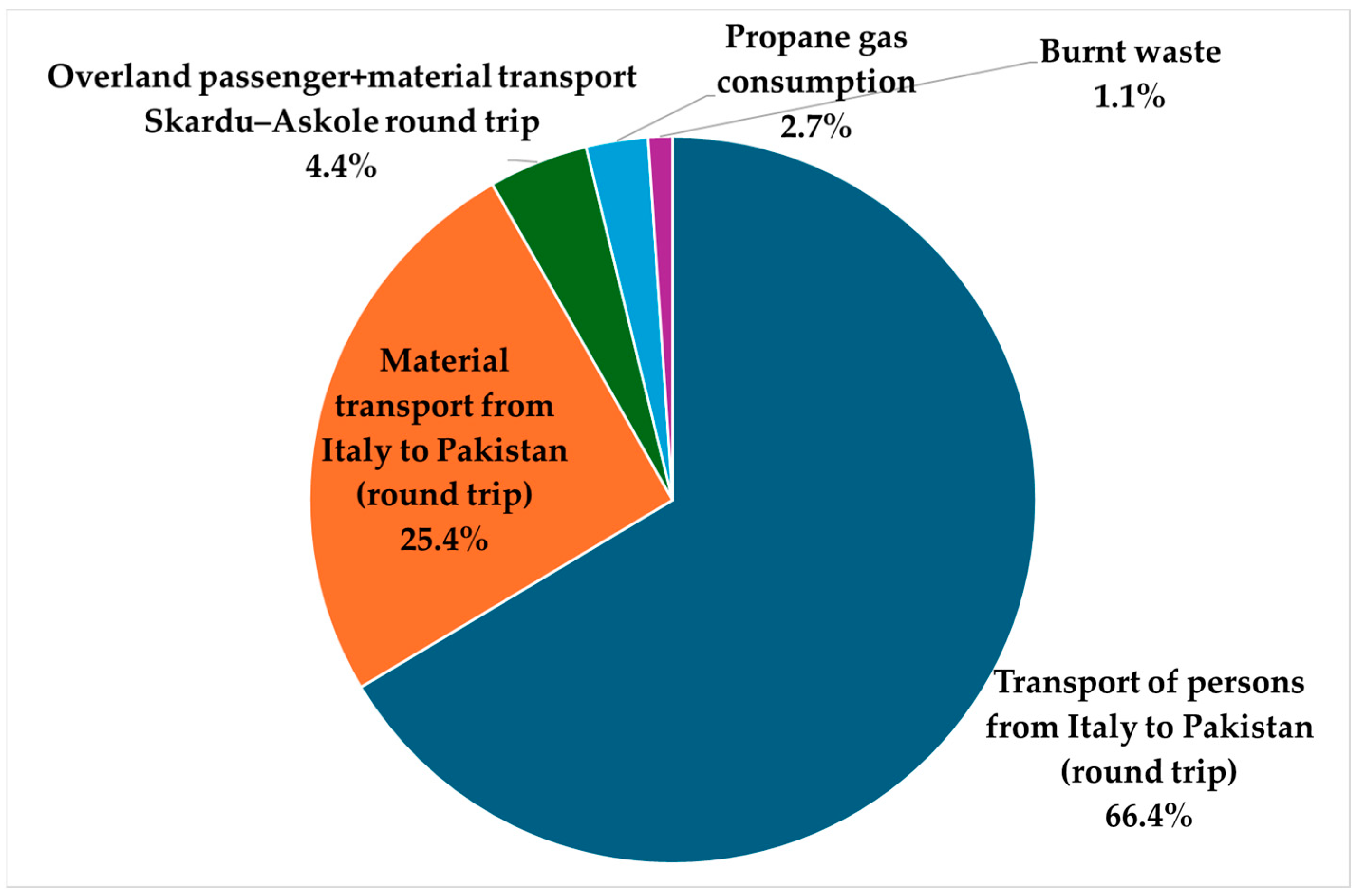

Overall, the 2024 K2 expedition from Italy had a carbon footprint of 27,654 kg CO2-eq. Air transport (i.e., the flight from Italy to Pakistan via Islamabad) was the largest source of emissions (91.7%). In particular, the movement of people (20) by air had the greatest impact followed by air freight (2100 kg outward and 600 kg return), 66.4% (18,360 kg CO2-eq) and 25.4% (7012 kg CO2-eq), respectively (Figure 4). Waste incineration had the lowest contribution (1.1%, 300 kg CO2-eq).

Figure 4.

Emissions of the 2024 K2 expedition sorted by category.

If we consider the team that flew from Italy and consisted of 20 people, the individual carbon footprint was 1383 kg CO2-eq/person. Obviously, the expedition involved a much larger team (i.e., four high-altitude porters plus a dozen other people such as cooks), especially on the route from Askole to K2 base camp. This is particularly noticeable in the amount of waste produced. In fact, the 300 kg of waste has to be divided not only by the 20 people (15 kg CO2-eq each) but also by the porters and the rest of the expedition members.

Considering the whole period of the expedition from Italy (54 days, from 16 June to 8 August 2024), the expedition had a daily impact of 512 kg CO2-eq/day. Taking into account the period of the actual mountaineering expedition (36 days, from 27 June to 1 August 2024), the daily impact was equal to 768 kg CO2-eq/day.

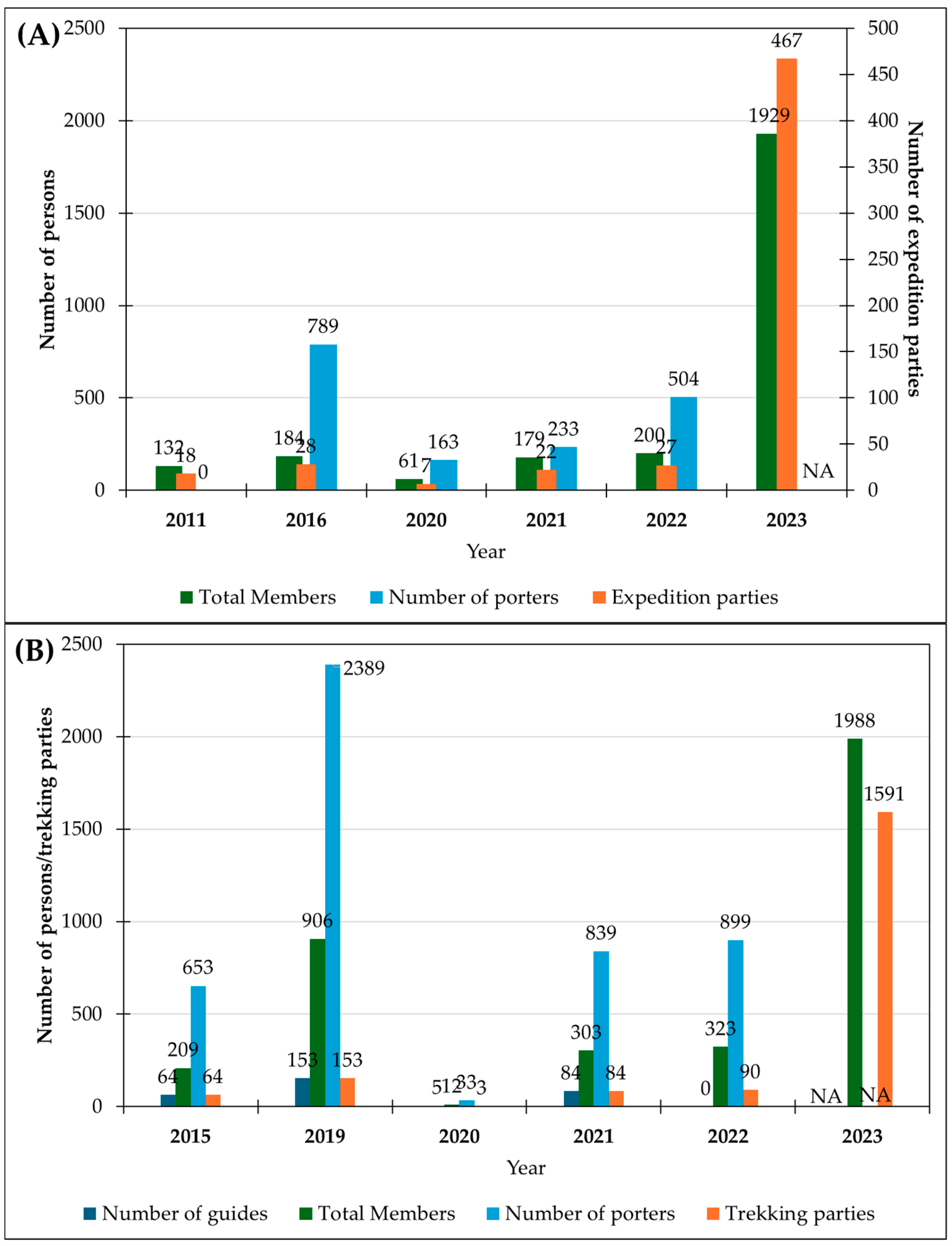

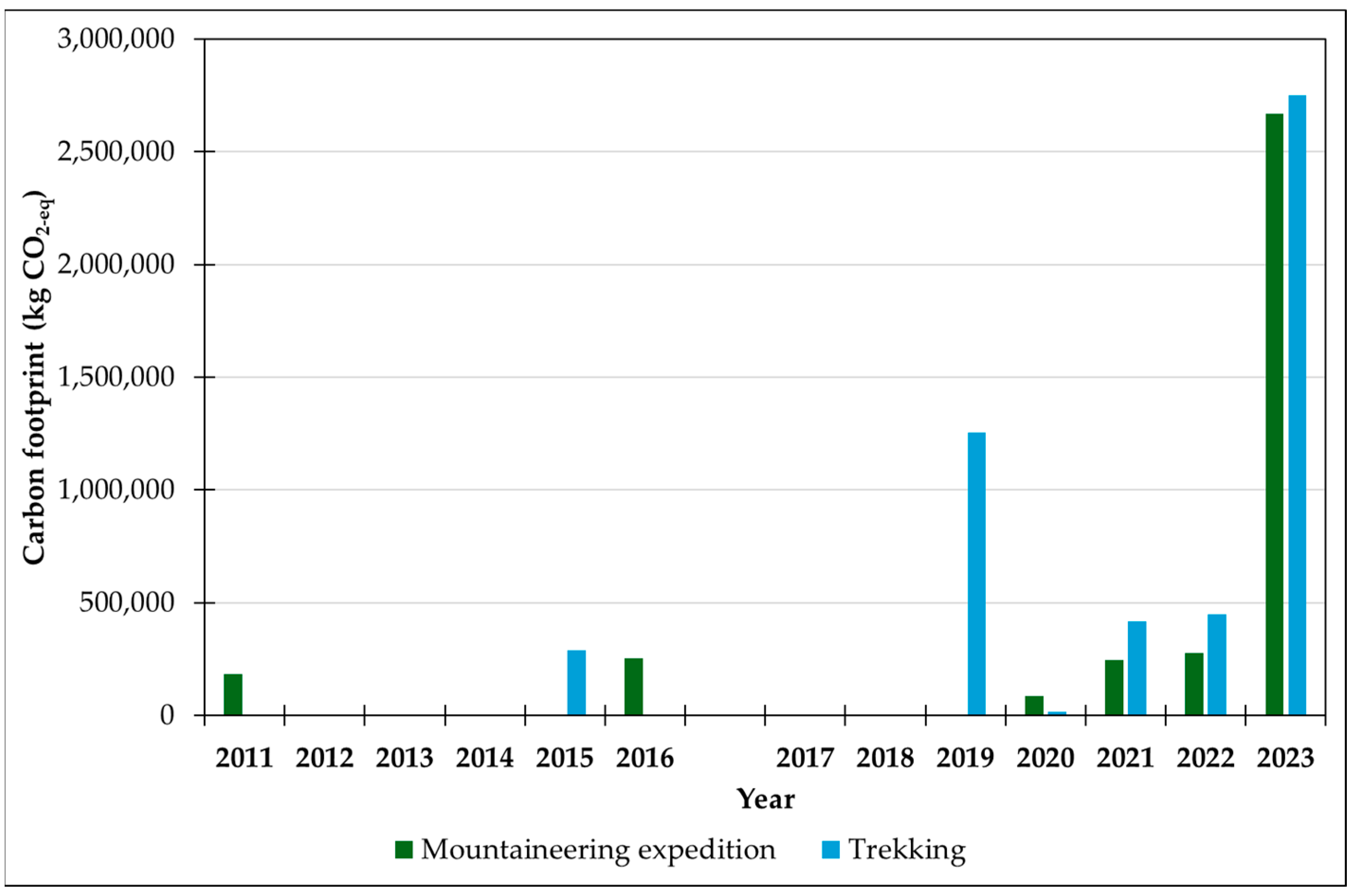

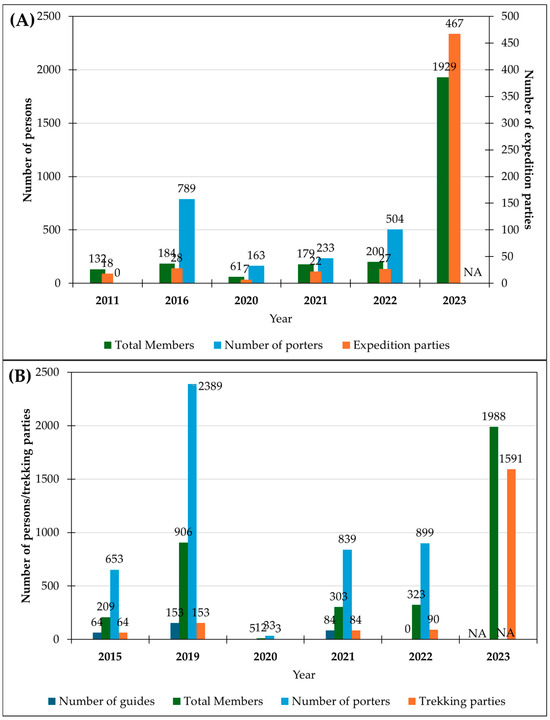

These estimates can be extended to all annual mountaineering expeditions (Figure 5A) and trekking parties (Figure 5B) using the data provided by the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC) [6]. There was a sharp decline in both types of activity by 2020, reflecting the general situation in Pakistan. In fact, in 2020, total international arrivals to Pakistan fell to just 163,000 (from 3.58 million in 2019, corresponding to a reduction of 95%) due to the global coronavirus outbreak [6,20]. The COVID-19 outbreak severely affected the tourism industry, causing unprecedented damage to the sector. The PTDC, in consultation with all stakeholders, promptly developed a tourism recovery strategy and began efforts to revive tourism in Pakistan, focusing on promoting safe internal tourism and gradually opening up to incoming foreign tourism. As a result, continued improvement was seen in 2021 and 2022. International arrivals reached 1.91 million in 2022. The growth in total international arrivals is also reflected in the surge in mountaineering and trekking expeditions in 2023 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of mountaineering expeditions (A) and trekking parties (B) in Gilgit-Baltistan, with the number of total members (i.e., those people directly involved in the expedition, such as climbers and support staff, who are officially registered as part of the team), porters, and guides from 2011 to 2023.

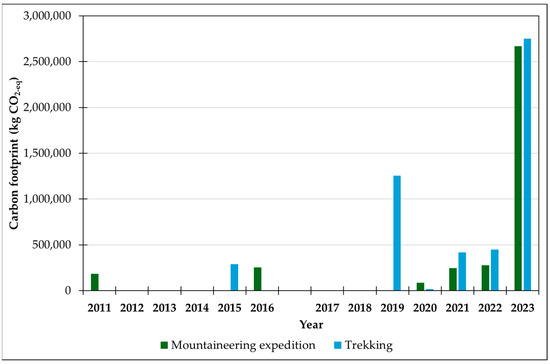

As trekking is less difficult than mountaineering, it is obviously chosen by more people. Our estimates based on data from the K2 expedition show that the largest contribution to GHG emissions comes from air travel. This is also the case for trekking. For this reason, we have assumed that the average carbon footprint per person calculated for the K2 expedition can also be considered approximately valid for trekking. Considering the number of participants in the mountaineering expeditions and trekking parties reported by [6,20], the annual impact in terms of carbon footprint was therefore estimated using the average per person value of the Italian expedition to K2 in 2024 (Figure 6). This is equivalent to a total of about 540 tons of CO2-eq per year in 2015–2016 and about ten times more in the last year for which tourism statistics are available (2023). These figures are influenced by the extremely high number of members in 2023: +1176% for mountaineering and +467% for trekking compared to the annual average of 151 and 351 members (taking into account the years 2011–2022 and 2015–2022, respectively). It is worth noting that in 2023, the number of expedition and trekking members is quite similar, whereas in previous years the former were less than half the number of the latter.

Figure 6.

Annual impact in terms of carbon footprint of mountaineering expeditions and trekking parties in Gilgit-Baltistan from 2011 to 2022.

The new 2024 Italian expedition underscored a significant evolution in the technologies used for expeditions, particularly in terms of environmental sustainability. Although no specific data are available for the first Italian expedition in 1954, we do know that there was a shift from reliance on fossil fuels in earlier expeditions to the adoption of solar energy in the recent one. In 1954, in the absence of today’s advanced technology, expeditions relied on fossil fuel generators to power base camps, resulting in significant GHG emissions. The combustion of diesel, especially at high altitudes, contributed to CO2 emissions and other GHGs that exacerbate climate change and hasten glacier melting [21]. In contrast, the 2024 expedition highlighted a shift towards sustainability, with solar panels powering operations such as lighting and communication at the base camp. Of course, transporting these panels from Italy increased the carbon footprint of the expedition, but this was offset by their higher efficiency and the reduced number of panels required compared to local alternatives. In fact, panels of this size and power were not available in Pakistan; the local panels had a much lower power output, which would have required the use of 40 solar panels to achieve the same power output. In addition, at the end of the expedition, the solar panels and batteries were donated to the Central Karakoram National Park (CKNP) for future use, contributing to the long-term sustainability of the region. Therefore, this not only demonstrated the feasibility of renewable energy in harsh environments but also helped significantly reduce the environmental footprint of the expedition by minimizing carbon emissions.

To assess the environmental impact of using solar panels instead of fossil fuels, a life cycle assessment (LCA) would be necessary. Although data from the first K2 expedition are unavailable, numerous studies have conducted LCAs to compare the overall environmental impact of solar panels versus fossil fuel generators (e.g., [21,22]). LCAs consider all stages of a product’s life cycle, from material extraction to disposal. While solar panels may initially have a higher environmental cost due to the energy required for production, transportation, and installation, research consistently shows that they outperform fossil fuel generators in the long run, particularly in terms of GHG emissions and ecological footprint [22]. For instance, recent studies [23,24] have shown that solar panels have a carbon payback period of approximately two years. This means that after this time, they operate with minimal environmental impact, unlike generators that continuously release harmful pollutants into the atmosphere throughout their operational lifespan. Furthermore, the use of recycled materials in solar panel production further enhances their sustainability, contributing to a circular economy and minimizing waste, which is particularly important in sensitive environments like K2.

Our findings indicate that the most critical factors undermining the sustainability of a high-altitude expedition are largely rooted in greenhouse gas emissions from air travel. Using current emission factors for air travel, in 1954, 18 people flew to and from Italy (out of a total of 30 expedition members) with an impact of 16,524 kg CO2-eq. Given that air travel accounted for 66.4% of the 2024 expedition, the 1954 expedition could have had at least a total impact of 24,889 kg CO2-eq, thus slightly lower than the one of the 2024 expedition but it does not include the impact of the use of diesel generators (replaced by photovoltaic panels in 2024). Similarly, for the 2004 expedition, with a total of 82 members plus the transport of an automatic weather station (180 kg) and an additional weight of 500 kg for the rest of the scientific material, the total impact was at least 116,914 kg CO2-eq (not including emissions from diesel generators).

Another consideration in assessing the evolution of the expedition’s environmental impact over time is the type of materials used. In fact, the clothing of the 1954 expedition was mainly made from natural fibers (e.g., cotton, wool and jute), whereas in recent decades synthetic fibers have prevailed over natural fibers. Synthetic textile fibers include polyamide, polyvinyl chloride, polyurethane/elastane, modacrylic, polyacrylonitrile, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and other polyesters. Textile microfibers contaminate both air and water [25,26]. Most of the microfiber pollution in water comes from laundry effluent, often via wastewater treatment plants [27]. Even technical equipment (e.g., ropes) now consists mainly of synthetic materials [28]. A high-altitude mountaineering expedition requires tents, sleeping bags, ropes, containers for water and food, technical clothing, and specialized equipment made of metal and plastic. Napper et al. (2020) [29] measured the concentration of microplastics in snow and water near the Everest summit and found contamination levels clearly associated with mountaineering activities. As a result, the ecological footprint in terms of potential release of plastics into the environment has unfortunately increased over time. Any mountaineering activity should therefore minimize the amount of material used and, above all, the amount released into the environment. Therefore, in addition to GHG emissions, waste management and disruption to local ecosystems are other issues. At high altitudes, particularly on peaks such as K2 and Everest (Asia), the accumulation of waste from non-biodegradable materials, including plastics, food packaging, and oxygen cylinders, remains a significant problem. Expeditions that last for long periods of time generate large amounts of waste, which is often left behind due to logistical challenges and has a negative impact on the environment [13]. Our results show that waste incineration accounts for only 1.1% of total expedition emissions. Therefore, not leaving the waste along the trek, but taking it all the way to Skardu to be incinerated, resulted in a lower environmental impact.

Furthermore, carbon emissions from fossil fuel-powered generators are substantial contributors to climate change [10]. Mountaineers and expedition teams often rely on fossil fuels for heating, cooking, and logistics, creating a large carbon footprint [7]. Additionally, the disturbance of local flora and fauna, such as deforestation for firewood and disruption of wildlife habitats, further exacerbates environmental degradation [30].

Within this context, increasing the sustainability of an expedition requires a multi-faceted approach that includes better waste management and renewable energy adoption. One of the most immediate ways to reduce environmental impact is by implementing more effective waste management strategies, such as mandating climbers and expedition teams to bring back their waste. For example, Nepal’s waste deposit system on Mount Everest requires climbers to pay a deposit that is refunded only if they return with a certain amount of waste [31]. In fact, in 2014, the Nepalese government introduced a rule commanding all mountaineering expeditions to return 8 kg of waste per person or forfeit a USD 4000 deposit. However, this regulation does not appear to have had the intended effect, maybe due to a lack of enforcement [31]. Although this approach was not easy to apply, it could be a model that could be adapted to other high-altitude regions such as K2.

Renewable energy in expeditions can also significantly reduce their carbon footprint. The 2024 K2 expedition, which employed solar panels instead of diesel generators, provides a successful example of how renewable energy can be harnessed even in extreme environments. Solar energy offers a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, especially in areas with limited access to traditional energy infrastructure [22]. By adopting renewable technologies, expedition teams can lower their reliance on fossil fuels and contribute less to climate change.

Several expeditions have made notable efforts to reduce their environmental and social impacts. For instance, clean-up expeditions such as the Extreme Everest 2010 initiative have focused on removing waste left behind on high-altitude mountains [32]. These operations have gained popularity, especially after the global media brought attention to the accumulation of refuse on peaks like Mount Everest. Although clean-up efforts pose their own risks, they have been instrumental in removing tons of waste from these regions [13].

In addition to waste management, to reduce their carbon footprint, expeditions are increasingly turning to renewable energy solutions. The Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station, a research base powered entirely by solar and wind energy, stands as a pioneering example in the polar regions [33]. This model demonstrates that even in the harshest environments, clean energy can be used to power operations, reducing the dependence on diesel fuel and lowering emissions.

With its rich culture, geographical and biological diversity, and history, Pakistan has great potential for tourism [34]. Nevertheless, the rapid growth of tourism in Pakistan is having a number of negative environmental impacts [15]. On the one hand, the construction of new tourism infrastructures degrades air and water quality, consumes natural areas, and reduces biodiversity. On the other hand, the expansion of energy-intensive tourism activities damages the environment by increasing CO2 emissions [35]. The main forms of tourism in Pakistan can be classified into four groups: (i) religious tourism, (ii) archaeological and historical tourism, (iii) ecotourism, and (iv) adventure tourism (e.g., the mountaineering considered in this study) [34]. Religious, archaeological and historical tourism tends to focus on religious monuments and historical sites, generally located in urban or peri-urban areas, with associated impacts mainly on waste and transport. Ecotourism is a responsible way to travel to fragile, pristine, and generally protected areas and strives to have minimal impact on the environment. It aims to raise tourists’ awareness of conservation issues, promote the economic development of local communities, and ensure respect for cultures and human rights. Although all these types of tourism activities generate carbon emissions, they generally have less impact on fragile ecosystems than mountain tourism. A study conducted in the northern part of Pakistan [36] showed that deforestation, loss of biodiversity, solid waste generation, water, air and noise pollution, and damage to cultural and heritage sites are the main environmental problems caused by mountain tourism activities in the three villages of Hunza and Diamer districts (Gilgit Baltistan).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated the sustainability of the 2024 K2 expedition from Italy. We found a total carbon footprint of 27,654 kg CO2-eq, equal to 1383 kg CO2-eq/person or to 512 kg CO2-eq/day and 768 kg CO2-eq/day (considering the whole period of 54 days and the period of the actual mountaineering expedition of 36 days, respectively). On the one hand, air transport had the greatest impact (91.7%) and waste incineration the lowest one (1.1%). In particular, the movement of people (20) by air was the largest source of emissions followed by air freight (2100 kg outward and 600 kg return), 66.4% (18,360 kg CO2-eq) and 25.4% (7012 kg CO2-eq), respectively.

Given the symbolic value of these areas in terms of the conservation of the planet’s most fragile areas, we believe it would be appropriate to create a legal and cultural framework to promote offsetting measures for high-altitude expeditions. To mitigate the environmental impact of the 2024 expedition, the expedition organizers have been working with the Central Karakoram National Park on environmental activities to offset CO2-eq emissions. For example, one activity that could help offset the environmental impacts calculated in this study is reforestation. Another possibility is carbon credits. As the price of carbon credits varies from region to region, according to the World Bank portal, the price in Italy is 61.30 USD/ ton of CO2 or 57.02 EUR/ton of CO2. Taking these costs into account, offsetting 27,654 kg of CO2-eq would cost 1695 USD or EUR 1577. These approaches seem feasible and effective in mitigating the environmental impact of expeditions like the K2 one.

To reduce the carbon footprint of future high-altitude expeditions, additional strategies can be implemented beyond those already in place in 2024. Renewable energy sources, such as solar panels, have proven effective for powering base camps, and their use could be extended to heating systems and other energy-intensive activities. To reduce transport emissions and waste, lightweight and durable equipment should be prioritized, while better collaboration with local authorities could improve waste management practices, including stricter enforcement of proper waste disposal. In addition, the adoption of carbon offsetting schemes suitable for high-altitude tourism could reduce emissions from air travel and other logistics. Encouraging group travel and optimizing transport logistics could also help reduce overall emissions. Finally, incorporating circular economy principles, such as the use of recycled materials in gear production, can minimize waste and reduce the long-term environmental footprint of expedition.

Despite the environmental impacts of high-altitude expeditions highlighted by our results, they can be an important tourism activity for (i) the socio-economic development of local (often poor) populations [15,36], (ii) raising awareness for the protection of high-altitude mountain environments [34], and (iii) promoting the establishment of protected areas and national parks. An example of this is what happened with K2, which led to the establishment of the Central Karakorum National Park (i.e., the highest protected area in the world). But in order to reach the world’s highest peaks, damage is being done to the environment, as this study shows. Therefore, we need to be aware of this damage, and if it cannot be avoided, it should be mitigated by taking all possible technical and common-sense measures to reduce its impact, and it should also be compensated with on-site restoration activities by supporting stakeholders and local governments in conservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D.; methodology, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D.; formal analysis, A.S. and M.M.; investigation, A.S., A.A., M.M., and G.A.D.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.A., M.M., and G.A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.S., A.A., M.M., and G.A.D.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D.; project administration, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D.; funding acquisition, A.S., M.M., and G.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted within the framework of the “Glaciers & Students” project, an inter- and multi-disciplinary project framed within proposals funded by the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development (AICS), an integral part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MAECI). AICS has entrusted the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) with the implementation of this cooperation initiative and acknowledges the contribution of the UNDP to its realization. “Glaciers & Students” was a project carried out under a contract between UNIMI and the recognized association EvK2CNR. The project aimed both to improve knowledge of Pakistani glaciers, which are numerous (the study area is part of the so-called Third Pole) and are both victims and witnesses of climate change, and to provide training opportunities for Pakistani students and technicians in key areas such as remote sensing, GIS, meteorology, and glaciology. Researchers involved in the study were also supported by Stelvio National Park (ERSAF), Sanpellegrino Levissima S.p.A., ECOFIBRE s.r.l., EDILFLOOR S.p.A., Geotex 2000 S.p.A. and Manifattura Fontana S.p.A. The 2024 expedition was realized by CAI with the support of the recognized association EvK2CNR to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of K2. The data relating to this expedition and processed in this paper were provided by EvK2CNR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Scott, D. Global Environmental Change and Mountain Tourism. In Tourism and Global Environmental Change; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell, D.; Messerli, B.; Ives, J.D. Mountains of the World: A Global Priority. Mt. Res. Dev. 1998, 18, 362–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.; Russo, L.; Parisi, F.; Notarianni, M.; Manuelli, S.; Carvao, S. Mountain Tourism—Towards a More Sustainable Path; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R.W.; Baxter, G.S.; Hockings, M. Resource Management in Tourism Research: A New Direction? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation. Statistics 2021; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022.

- Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation. Pakistan Tourism Barometer (Edition-2022). 2022. Available online: https://tourism.gov.pk/advertisements/Pakistan%20Tourism%20Barometer%20-%20Edition%202022.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Kuniyal, J.C. Mountain Expeditions: Minimising the Impact. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The Carbon Footprint of Global Tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Transport-Related CO2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector—Modelling Results; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Klöwer, M.; Allen, M.R.; Lee, D.S.; Proud, S.R.; Gallagher, L.; Skowron, A. Quantifying Aviation’s Contribution to Global Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Dang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, P.; Kang, S.; Dunn-Rankin, D. Emissions from Solid Fuel Cook Stoves in the Himalayan Region. Energies 2019, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, S.; Hassan, N.M.; Khattak, M.N.; Moustafa, M.A.; Fakhri, M.; Ahmad, Z. Impact of Tourist’s Environmental Awareness on pro-Environmental Behavior with the Mediating Effect of Tourist’s Environmental Concern and Moderating Effect of Tourist’s Environmental Attachment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semernya, L.; Ramola, A.; Alfthan, B.; Giacovelli, C. Waste Management Outlook for Mountain Regions: Sources and Solutions. Waste Manag. Res. 2017, 35, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.W.; Shu, H.; Javid, K.; Pervaiz, S.; Mustafa, F.; Raza, D.; Ahmed, B.; Quddoos, A.; Al-Ahmadi, S.; Hatamleh, W.A. Wetland Identification through Remote Sensing: Insights into Wetness, Greenness, Turbidity, Temperature, and Changing Landscapes. Big Data Res. 2024, 35, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of Tourism Development upon Environmental Sustainability: A Suggested Framework for Sustainable Ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.; Agrawal, M.; Pandey, J.S. Carbon Footprint: Current Methods of Estimation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 178, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senese, A.; Caspani, A.C.; Lombardo, L.; Manara, V.; Diolaiuti, G.A.; Maugeri, M. A User-Friendly Tool to Increase Awareness about Impacts of Human Daily Life Activities on Carbon Footprint. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserini, S.; Baglione, P.; Cottafava, D.; Gallo, M.; Laio, F.; Magatti, G.; Maggi, V.; Maugeri, M.; Moreschi, L.; Perotto, E.; et al. Ida fattori di emissione di CO2 per consumi energeti-ci E trasporti per gli inventari di gas serra degli atenei italiani. Ing. Dell’ambiente 2019, 6, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnke, B. Waste Incineration—An Important Element of the Integrated Waste Management System in Germany. Waste Manag. Res. 1992, 10, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC). Pakistan Tourism Barometer (Edition-2023-24); Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC): Islamabad Capital Territory, Pakistan, 2023.

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yap, P.S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, Environmental, and Economic Consequences of Integrating Renewable Energies in the Electricity Sector: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, N.Y.; Troldborg, M.; Kington, B.; Aalders, I.; Hough, R.L. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Renewable Energy Sources: A Review of Lifecycle Considerations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramendia, E.; Brockway, P.E.; Taylor, P.G.; Norman, J.B.; Heun, M.K.; Marshall, Z. Estimation of Useful-Stage Energy Returns on Investment for Fossil Fuels and Implications for Renewable Energy Systems. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.H.; Huang, L.H.; Lou, S.; Kuo, C.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Chian, K.J.; Chien, H.T.; Hong, H.F. Assessment of the Carbon Footprint, Social Benefit of Carbon Reduction, and Energy Payback Time of a High-Concentration Photovoltaic System. Sustainability 2017, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Edo, C.; Aguilera, Á.; Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Pulido-Reyes, G.; González-Toril, E.; Osuna, S.; de Diego-Castilla, G.; Leganés, F.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; et al. Occurrence and Transport of Microplastics Sampled within and above the Planetary Boundary Layer. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, F.; Cocca, M.; Avella, M.; Thompson, R.C. Microfiber Release to Water, Via Laundering, and to Air, via Everyday Use: A Comparison between Polyester Clothing with Differing Textile Parameters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3288–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senese, A.; Pecci, M.; Ambrosini, R.; Diolaiuti, G.A. MOUNTAINPLAST: A New Italian Plastic Footprint with a Focus on Mountain Activities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Davies, B.F.R.; Clifford, H.; Elvin, S.; Koldewey, H.J.; Mayewski, P.A.; Miner, K.R.; Potocki, M.; Elmore, A.C.; Gajurel, A.P.; et al. Reaching New Heights in Plastic Pollution—Preliminary Findings of Microplastics on Mount Everest. One Earth 2020, 3, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S. National Parks and ICCAs in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, S.; Ghimire, A.; Dangi, M.B. Generation, Characterization, and Environmental Implications of Solid Waste and Its Management in the Everest Region. Nepal J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrud, M.A. Polluting the Pristine: Using Mount Everest to Teach Environmental Ethics. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 26–29 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lucci, J.J.; Alegre, M.; Vigna, L. Renewables in Antarctica: An Assessment of Progress to Decarbonize the Energy Matrix of Research Facilities. Antarct. Sci. 2022, 34, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.I.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shahbaz, M. Pakistan Tourism Industry and Challenges: A Review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andlib, Z.; Salcedo-Castro, J. The Impacts of Tourism and Governance on CO2 Emissions in Selected South Asian Countries. Etikonomi 2021, 20, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- us Saqib, N.; Yaqub, A.; Amin, G.; Khan, I.; Faridullah; Ajab, H.; Zeb, I.; Ahmad, D. The Impact of Tourism on Local Communities and Their Environment in Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan: A Local Community Perspective. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2019, 7, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).