Comparing the Use of Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms to Organize Kitting Systems Within Green Supply Chain Management Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Most logistics optimization projects are based on the principles of lean manufacturing. However, most research, such as Womack and Jones (1996), addresses the issue strictly from a production waste minimization perspective rather than that of logistics [7].

- This study fits well within the literature in which green manufacturing is integrated with lean manufacturing—a field of study that is still in its developmental stage.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)

3.2. Genetic Algorithms

4. Implementation via Genetic Algorithms and Ant Colony Optimization

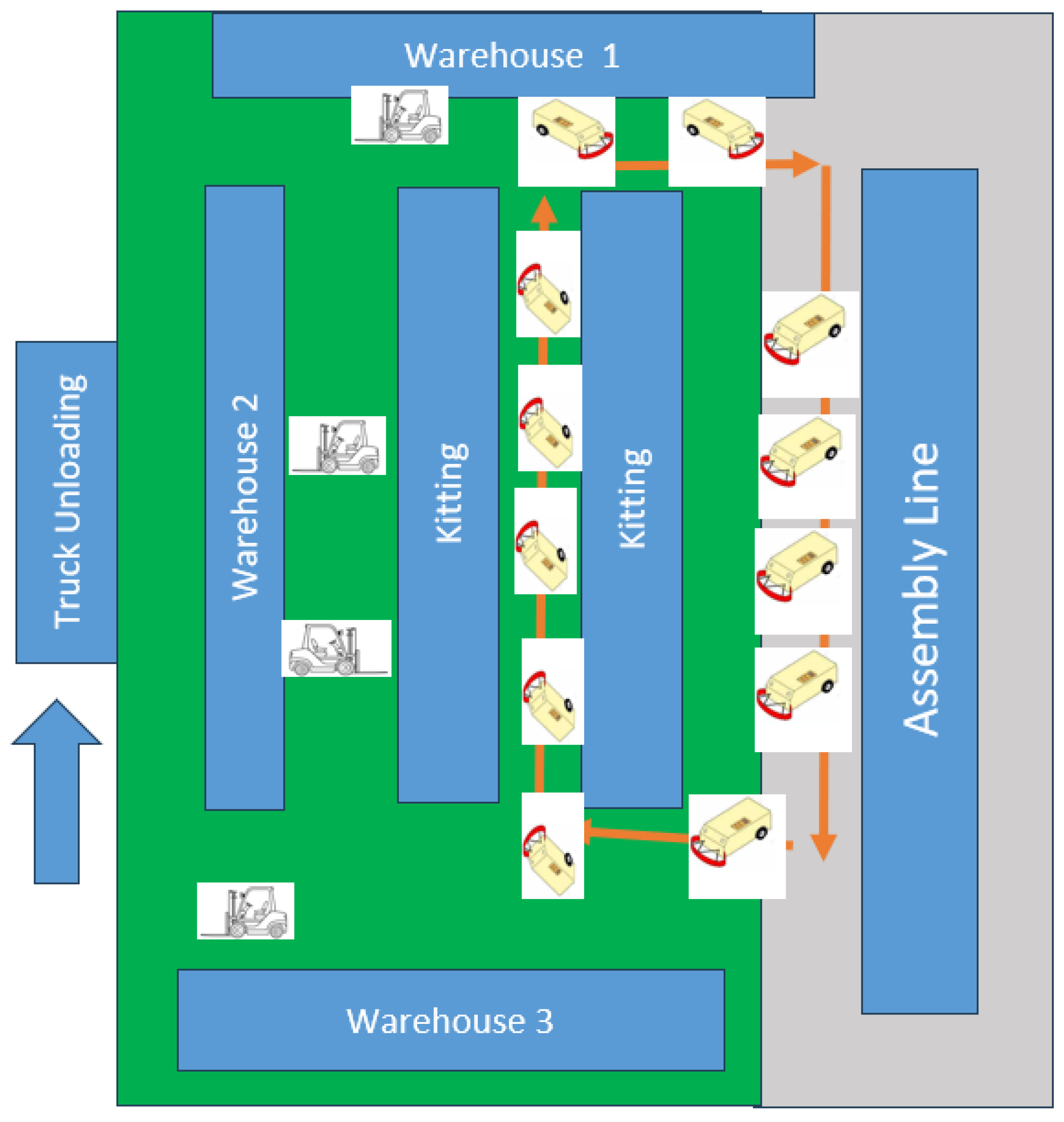

4.1. Problem Definition

4.2. GA Implementation via Python

| Algorithm 1. GA Algorithm Steps |

|

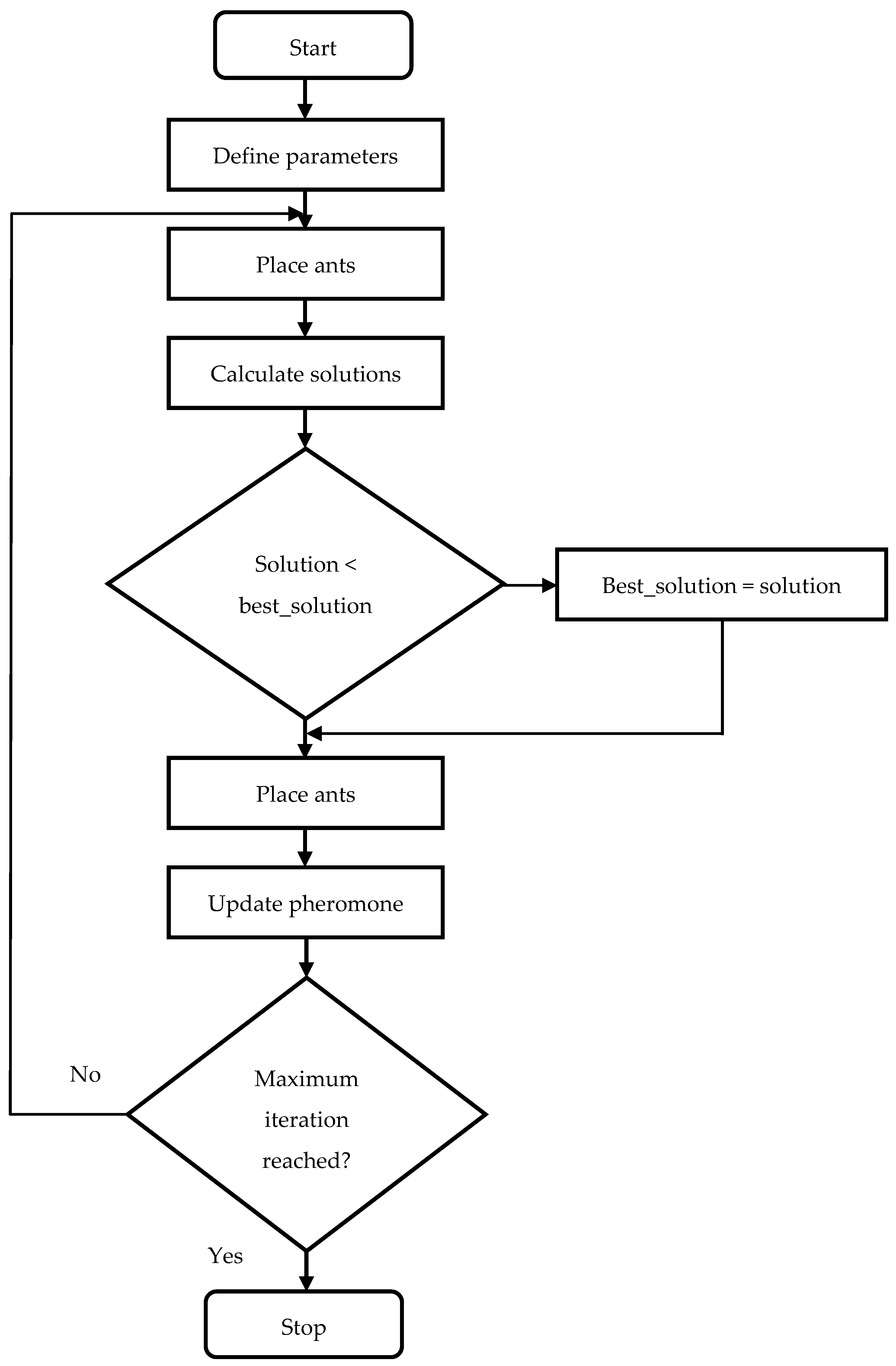

4.3. ACO Implementation via Python

| Algorithm 2. ACO Algorithm Steps |

|

4.4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez-Flores, R.B.; Cruz-Sotelo, S.E.; Ojeda-Benitez, S.; Ramírez-Barreto, M.E. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Gambardella, L.M. Ant colonies for the traveling salesman problem. Biosystems 1997, 43, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seman, N. Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Research Direction. Int. J. Manag. Value Supply Chain. 2012, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q. Artificial Intelligence in Logistics: Implications for Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, C. Ant colony optimization: Introduction and recent trends. Phys. Life Rev. 2005, 2, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/34563325/James_P_Womack_Lean_Thinking (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature review of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y. Collaborative Strategies in Green Supply Chains: A Case Study Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 789–804. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T. Agile Supply Chains and Sustainability: The Interconnectedness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 204–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, J. Integrating Circular Economy into Logistics: A Sustainable Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Stützle, T. Ant Colony Optimization; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, S.; Niaki, S.T.A. An Analytical Decision-Making Model for Integrated Green Supply Chain Problems: A Computational Intelligence Solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 464, 142716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.; Chakraborty, S. Ant Colony Optimization—Recent Variants, Application and Perspectives. In Applications of Ant Colony Optimization and its Variants; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. A Dynamic Scheduling Method for Logistics Supply Chain Based on Adaptive Ant Colony Algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogareda, A.M.; Del Ser, J.; Osaba, E.; Camacho, D. On the design of hybrid bio-inspired meta-heuristics for complex multiattribute vehicle routing problems. Expert Syst. 2020, 37, e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Zhang, H.; Yan, X.; Miao, Q. Green Supply Chain Optimization Based on Two-Stage Heuristic Algorithm. Processes 2024, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Shrivastav, S.K.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Panigrahi, R.R.; Mardani, A.; Cavallaro, F. Sustainable Supply Chain Management, Performance Measurement, and Management: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Yu, L.; Zhao, X.; Jia, F.; Han, F.; Hou, H.; Liu, Y. A multi-objective optimization approach for green supply chain network design for the sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) industry. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Blum, C. Ant colony optimization theory: A survey. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2005, 344, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Maniezzo, V.; Colorni, A. Ant system: Optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B (Cybern.) 1996, 26, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasian, M.; Sazvar, Z.; Mohammadisiahroudi, M. A hybrid optimization method to design a sustainable resilient supply chain in a perishable food industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 6080–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asha, L.N.; Dey, A.; Yodo, N.; Aragon, L.G. Optimization approaches for multiple conflicting objectives in sustainable green supply chain management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xie, D.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, J. Green supply chain management: A renewable energy planning and dynamic inventory operations for perishable products. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 8924–8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xie, W.; Wei, M.; Xie, X. Multi-objective sustainable supply chain network optimization based on chaotic particle—Ant colony algorithm. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Li, J.-L.; Liu, M.-Y.; Jiao, B.-B. An Enhanced Ant Colony Algorithm-Based Low-Carbon Distribution Control Method for Logistics Leveraging Internet of Things (IoT). Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2023, 2023, 555221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revanna, J.K.C.; Veerabhadrappa, R. Analysis of Optimal Design Model in Vehicle Routing Problem based on Hybrid Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N), Greater Noida, India, 16–17 December 2022; pp. 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT Sustainable Supply Chain Lab. State of Supply Chain Sustainability. MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics. 2023. Available online: https://sscs.mit.edu/2023-implications/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R. Digital Technologies in Green Supply Chains: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Herrmann, F.F.; Dias MF, P.; Rodrigues, G.S.; Butturi, M.A. Green supply chain management in the Southern Brazilian rice industry: A survey and structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R. The Role of Agility in Sustainable Supply Chains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Masruroh, N.A.; Rifai, A.P.; Mulyani, Y.P.; Ananta, V.S.; Luthfiansyah, M.F.; Winati, F.D. Priority-based multi-objective algorithms for green supply chain network design with disruption consideration. Prod. Eng. 2024, 18, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Goetschalckx, M.; McGinnis, L.F. Research on warehouse design and performance evaluation: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, G.H.; He, Y.; Pakdel, S.H. Multi-objective green closed-loop supply chain management with bundling strategy, perishable products, and quality deterioration. Mathematics 2024, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoud, E.; Abdel-Aal, M.A.M.; Sakaguchi, T.; Uchiyama, N. Robust Optimization for a Bi-Objective Green Closed-Loop Supply Chain with Heterogeneous Transportation System and Presorting Consideration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohammadi, A.M.; Abedsoltan, H.; Goli, A.; Ali, I. Multi-objective dragonfly algorithm for optimizing a sustainable supply chain under resource sharing conditions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koster, R.; Le-Duc, T.; Roodbergen, K.J. Design and control of warehouse order picking: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 182, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haupt, R.L.; Haupt, S.E. Practical Genetic Algorithms; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, K.A. Evolutionary Computation: A Unified Approach; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michalewicz, Z. Genetic Algorithms + Data Structures = Evolution Programs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour | Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour | Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1001 | 8 | 60 | X1031 | 19 | 24 | X1061 | 10 | 15 |

| X1002 | 19 | 12 | X1032 | 9 | 20 | X1062 | 6 | 18 |

| X1003 | 9 | 10 | X1033 | 8 | 14 | X1063 | 6 | 12 |

| X1004 | 8 | 12 | X1034 | 10 | 20 | X1064 | 5 | 20 |

| X1005 | 15 | 60 | X1035 | 6 | 10 | X1065 | 16 | 8 |

| X1006 | 10 | 15 | X1036 | 6 | 5 | X1066 | 18 | 14 |

| X1007 | 6 | 12 | X1037 | 5 | 10 | X1067 | 9 | 8 |

| X1008 | 6 | 10 | X1038 | 16 | 12 | X1068 | 14 | 7 |

| X1009 | 5 | 15 | X1039 | 18 | 10 | X1069 | 19 | 5 |

| X1010 | 16 | 10 | X1040 | 6 | 20 | X1070 | 9 | 16 |

| X1011 | 18 | 15 | X1041 | 9 | 7 | X1071 | 13 | 10 |

| X1012 | 6 | 40 | X1042 | 14 | 16 | X1072 | 19 | 7 |

| X1013 | 9 | 10 | X1043 | 19 | 4 | X1073 | 6 | 18 |

| X1014 | 14 | 5 | X1044 | 9 | 14 | X1074 | 11 | 8 |

| X1015 | 19 | 10 | X1045 | 13 | 30 | X1075 | 7 | 18 |

| X1016 | 9 | 12 | X1046 | 20 | 20 | X1076 | 8 | 8 |

| X1017 | 13 | 20 | X1047 | 19 | 16 | X1077 | 7 | 7 |

| X1018 | 20 | 40 | X1048 | 6 | 10 | X1078 | 16 | 18 |

| X1019 | 19 | 5 | X1049 | 11 | 7 | X1079 | 10 | 8 |

| X1020 | 6 | 12 | X1050 | 7 | 10 | X1080 | 20 | 8 |

| X1021 | 11 | 6 | X1051 | 8 | 7 | X1081 | 15 | 8 |

| X1022 | 18 | 60 | X1052 | 7 | 16 | X1082 | 19 | 8 |

| X1023 | 7 | 12 | X1053 | 16 | 10 | X1083 | 19 | 10 |

| X1024 | 8 | 10 | X1054 | 10 | 7 | X1084 | 9 | 5 |

| X1025 | 7 | 5 | X1055 | 20 | 7 | X1085 | 8 | 12 |

| X1026 | 16 | 12 | X1056 | 15 | 7 | X1086 | 10 | 10 |

| X1027 | 10 | 6 | X1057 | 19 | 7 | X1087 | 6 | 14 |

| X1028 | 20 | 6 | X1058 | 19 | 12 | X1088 | 6 | 14 |

| X1029 | 15 | 6 | X1059 | 9 | 5 | X1089 | 5 | 15 |

| X1030 | 19 | 6 | X1060 | 8 | 13 | X1090 | 16 | 14 |

| Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour | Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour | Subcomponent | Quantity in Packages | Average Consumption per Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1091 | 18 | 21 | X1121 | 8 | 6 | X1151 | 11 | 11 |

| X1092 | 9 | 9 | X1122 | 7 | 9 | X1152 | 10 | 5 |

| X1093 | 14 | 8 | X1123 | 16 | 6 | X1153 | 20 | 5 |

| X1094 | 19 | 7 | X1124 | 10 | 5 | X1154 | 15 | 11 |

| X1095 | 9 | 8 | X1125 | 20 | 5 | X1155 | 19 | 5 |

| X1096 | 19 | 8 | X1126 | 15 | 5 | X1156 | 10 | 6 |

| X1097 | 6 | 14 | X1127 | 19 | 5 | X1157 | 20 | 6 |

| X1098 | 11 | 9 | X1128 | 9 | 10 | X1158 | 19 | 6 |

| X1099 | 7 | 14 | X1129 | 6 | 7 | X1159 | 11 | 15 |

| X1100 | 8 | 9 | X1130 | 16 | 10 | X1160 | 11 | 15 |

| X1101 | 7 | 8 | X1131 | 9 | 12 | X1161 | 11 | 10 |

| X1102 | 16 | 14 | X1132 | 14 | 15 | X1162 | 11 | 20 |

| X1103 | 10 | 9 | X1133 | 19 | 6 | X1163 | 30 | 5 |

| X1104 | 20 | 9 | X1134 | 19 | 15 | X1164 | 30 | 6 |

| X1105 | 15 | 9 | X1135 | 11 | 10 | X1165 | 30 | 7 |

| X1106 | 19 | 9 | X1136 | 8 | 12 | X1166 | 30 | 8 |

| X1107 | 19 | 2 | X1137 | 7 | 15 | X1167 | 30 | 9 |

| X1108 | 9 | 10 | X1138 | 10 | 10 | X1168 | 30 | 10 |

| X1109 | 8 | 9 | X1139 | 20 | 10 | X1169 | 30 | 11 |

| X1110 | 6 | 6 | X1140 | 15 | 10 | X1170 | 30 | 4 |

| X1111 | 6 | 12 | X1141 | 19 | 10 | X1171 | 19 | 10 |

| X1112 | 16 | 6 | X1142 | 9 | 8 | X1172 | 19 | 20 |

| X1113 | 9 | 6 | X1143 | 19 | 9 | X1173 | 19 | 12 |

| X1114 | 14 | 9 | X1144 | 11 | 4 | X1174 | 19 | 18 |

| X1115 | 19 | 8 | X1145 | 8 | 8 | X1175 | 22 | 20 |

| X1116 | 9 | 10 | X1146 | 10 | 4 | X1176 | 22 | 10 |

| X1117 | 19 | 9 | X1147 | 20 | 4 | X1177 | 22 | 30 |

| X1118 | 6 | 6 | X1148 | 15 | 4 | X1178 | 17 | 20 |

| X1119 | 11 | 5 | X1149 | 19 | 4 | X1179 | 17 | 10 |

| X1120 | 7 | 6 | X1150 | 19 | 11 | X1180 | 17 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Şenaras, O.M.; İnanç, Ş.; Eren Şenaras, A.; Öngen Bilir, B. Comparing the Use of Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms to Organize Kitting Systems Within Green Supply Chain Management Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052001

Şenaras OM, İnanç Ş, Eren Şenaras A, Öngen Bilir B. Comparing the Use of Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms to Organize Kitting Systems Within Green Supply Chain Management Practices. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052001

Chicago/Turabian StyleŞenaras, Onur Mesut, Şahin İnanç, Arzu Eren Şenaras, and Burcu Öngen Bilir. 2025. "Comparing the Use of Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms to Organize Kitting Systems Within Green Supply Chain Management Practices" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052001

APA StyleŞenaras, O. M., İnanç, Ş., Eren Şenaras, A., & Öngen Bilir, B. (2025). Comparing the Use of Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms to Organize Kitting Systems Within Green Supply Chain Management Practices. Sustainability, 17(5), 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052001