Abstract

This study explored the impact of psychological distance, media coverage, and guilt on communication behavior and eco-friendly actions and found that environmental interest was a significant predictor of behavior. The findings indicate that perceptions of the severity of the climate crisis and media coverage facilitated information seeking and interpersonal communication, which in turn led to eco-friendly behavior. Additionally, guilt strongly predicted information seeking and eco-friendly product purchase intention. Information seeking and interpersonal communication positively influenced eco-friendly product purchases and energy conservation. Women and younger individuals favored face-to-face communication and public transport, while older individuals focused on energy conservation and eco-friendly purchases. Perceptions of climate crisis severity and media coverage influenced communication and eco-friendly purchases. Guilt strongly predicted information seeking and purchase intention, which emphasizes the effectiveness of emotion-based messages. The findings highlight the need for targeted strategies across demographics and political orientations to promote pro-environmental behavior.

1. Introduction

According to a 2023 report by WWF Korea, Koreans’ perceptions of environmental issues have evolved over time. In 2018, environmental concerns were seen as fragmented, but by 2022, they were recognized as interconnected. Media coverage also changed, with keywords shifting from broad environmental terms in 2018 to a more diverse range of topics in 2022, including consumer behavior, carbon neutrality, fine dust, and business agreements. Additionally, an analysis of YouTube comments revealed that public awareness and concern about environmental crises spread more rapidly through social media than through traditional news outlets [1]. As awareness grows and environmental issues become more complex, the study highlighted the importance of eco-friendly behaviors.

The escalating climate crisis underscores the urgent need to elucidate the factors that drive pro-environmental behavior [2,3]. Effective environmental management requires collective action at the local, regional, national, and global levels. Feldman and Hart [4] found that message content, more than media framing, significantly influences perceptions of climate change severity and behavioral intention for mitigation or adaptation, which highlights its impact on public behavior [4].

Scholars identified cognitive awareness, including knowledge on the severity of climate crisis, as a key predictor of pro-environmental behavior. Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) argued that individuals who understand the consequences of climate change and its severity are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly behavior [5].

Cognitive awareness is essential for action, but emotional engagement, perceived efficacy, and social norms are crucial for bridging the gap between knowledge and behavior. Combining knowledge with emotional engagement and action opportunities fosters pro-environmental behavior [6].

Emotions related to the climate crisis, such as guilt, pride, and anger, also form pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Harth, Leach, and Kessler (2013) demonstrated that guilt about environmentally harmful actions encourages individuals to feel responsible and take compensatory actions [7]. Similarly, their analysis of guilt, anger, and pride revealed that individuals who feel guilt over the harmful environmental actions of their group are more likely to take responsibility and adopt compensatory behaviors, while self-esteem reinforces continually eco-friendly actions. Conversely, anger negatively impacts pro-environmental intentions [8].

This study examines the combined influence of cognitive and emotional factors on communication behavior and pro-environmental actions by exploring the effects of emotional variables and climate crisis severity on eco-friendly behavior. Information seekers exhibit stronger pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Choo (2023) investigated the effects of information seeking on environmental attitudes and behaviors and found that individuals who frequently seek information on climate change are more aware of its severity and display more positive attitudes toward environmental protection. A higher frequency of information seeking was also correlated with a stronger intention to act in environmentally friendly ways [9]. Similarly, Hovick et al. (2021) reported that exposure to environmental health risk messages increases risk perceptions, which motivates individuals to seek information and adopt behaviors that reduce environmental impacts [10]. Han and Xu (2020) mentioned that interpersonal communication, especially with family and friends, strongly increased environmental risk awareness and promoted pro-environmental behavior. Social media was effective when combined with interpersonal communication, whereas traditional media exhibited no direct impact [11].

This study explores how cognitive and emotional factors, including awareness and emotional engagement with the climate crisis, drive communication behavior and eco-friendly action, thus offering insights for effective climate advocacy strategies. This study examines how perceptions of the climate crisis, media framing, and guilt influence communication and eco-friendly behavior. This study utilized quantitative research methods to explore the relationships between emotions, including those related to the climate crisis and guilt, communication behaviors, and eco-friendly actions. The data for this analysis were obtained from the annual surveys conducted by the Korea Institute of Environmental Policy Evaluation (KEI). Understanding how cognitive factors and the guilt associated with psychological distance drive eco-friendly behavior is essential for developing effective climate change communication strategies. Given the impact of interpersonal communication on eco-friendly behavior, policymakers, businesses, and media organizations can play a crucial role in structuring climate messages and promoting sustainable consumer and societal behaviors.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Climate Crisis, Sustainability, and Eco-Friendly Actions

The climate crisis, driven by human activities such as fossil fuel consumption and deforestation, causes global warming, extreme weather, biodiversity loss, and rising sea levels. It threatens sustainability by depleting resources, disrupting ecosystems, and worsening social inequality. Sustainability is a development approach that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs [12].

Proposed by Olson (1965) [13], collective action theory emphasizes the importance of individual contributions in achieving group goals. According to this theory, in solving the climate crisis, individual eco-friendly practices (e.g., waste reduction, energy conservation, and support of sustainable products) cumulatively contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and resource depletion [2]. Social practice theory emphasizes how everyday practices are shaped by cultural norms, material conditions and individual actions, in which small individual actions can trigger wider social change, normalizing sustainability and creating systemic change.

Eco-friendly behavior refers to actions taken by individuals to minimize negative impacts on the environment based on factors such as personal values, social norms, and external influences [5,7,9]. Specifically, it refers to environmentally friendly behavior in daily life such as energy conservation, recycling, and use of public transportation. In addressing the climate crisis, individual actions can drive important collective change, and consumer demand. for eco-friendly products can foster changes in markets and encourage policymakers to implement sustainable regulations. Notably, individual eco-friendly actions can help solve the climate crisis by relying on public support and cooperation.

In the same context, discussions on sustainability emphasize the role of individual and collective actions in solving the climate crisis. Theories, such as value–belief–norm theory (VBN) and social practice theory examine how attitudes, norms, and everyday practices shape environmental behavior [14]. Many factors influence the relationship between the climate crisis and individual behavior. According to VBN theory, behavior is influenced by values, beliefs, and perceived obligations [14]. Awareness of the climate crisis is central to green action. People with altruistic or eco-centric values are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior. If individuals recognize the negative impacts and severity of the crisis, then they are motivated to act sustainably. Those aware of the crisis but do not practice eco-friendly behavior may experience cognitive dissonance, which prompts them to adopt environmentally friendly actions to resolve it.

2.2. Interconnections Between Psychological Distance, Interpersonal Communication, and Environmental Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) explains various social behaviors, including individual eco-friendly actions. According to TPB, human behavior is determined by behavioral intention, which is shaped by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [8]. Based on this theoretical framework, this study examines the role of perceptions and emotional factors related to environmental issues as predictors of eco-friendly behavior, with a particular focus on the moderating effect of interpersonal communication [15].

Interpersonal communication directly influences subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, two key components of TPB. Through the process of sharing environmental information with others, individuals may experience increased social pressure to engage in eco-friendly behavior, thereby reinforcing subjective norms. Additionally, interpersonal communication facilitates the exchange of practical knowledge on eco-friendly practices, enhancing perceived behavioral control by increasing individuals’ confidence in their ability to act. Moreover, interpersonal discussions about environmental issues can reduce psychological distance, making such issues feel more personally relevant and thereby influencing behavioral change [16].

In summary, a shorter psychological distance leads to a more positive attitude toward eco-friendly behavior. Meanwhile, interpersonal communication strengthens subjective norms and enhances perceived behavioral control, reinforcing the likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental actions in accordance with the TPB framework.

This study explores how perceptions of the climate crisis, emotions such as guilt, and media framing influence communication behavior and environmental actions. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) provides a foundational framework for understanding how an individual’s attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control affect their intention to engage in eco-friendly behavior. The concept of psychological distance, a cognitive element in this study, aligns with TPB’s notion that perceptions shape attitudes and offers a basis for explaining how factors such as guilt and media framing influence eco-friendly actions. The key moderating variable in this study, interpersonal communication, impacts subjective norms (social pressure to behave in an eco-friendly manner) and perceived behavioral control (confidence in one’s ability to act), further supporting the TPB’s assertion that perceptions shape attitudes and behaviors.

The relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and actions in this study is complex and dynamic, influenced by a range of cognitive, emotional, and situational factors. Various theories attempt to explain how these elements interact, but the path from knowledge to behavior is not always straightforward. For instance, individuals may feel motivated to protect the environment due to cognitive dissonance, yet engage in excessive consumption. When psychological distance from environmental issues is high, individuals’ motivation to engage in eco-friendly behavior decreases. Moreover, social and economic systems that promote environmentally harmful behaviors, such as industrial production and endless consumption, can hinder individuals’ ability to adopt eco-friendly behaviors. Self-interest can also disrupt environmental actions [17]. Emotions like fear, hope, anger, and guilt, as discussed by Kleres and Wettergren (2017), interact with individuals’ motivation to engage in climate activism. These emotional responses can either drive action or become barriers, depending on how they are framed and managed. Understanding the impact of these emotions on behavior is critical for designing effective communication strategies that promote sustainable actions and policy change [15].

This study focuses on how emotional and cognitive factors shape decision-making and behavior in the context of environmental action. Knowledge, attitudes, and actions are interconnected, but their relationships are influenced by various psychological, social, and situational factors. These interactions do not always follow a linear progression, making it essential to understand their complexity in order to predict and encourage pro-environmental behavior.

2.3. Psychological Distance from the Climate Crisis and Environmental Behavior

Recognizing the severity of the impacts of climate change increases one’s sense of urgency and encourages environmentally friendly behavior. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) explains how the perception of the severity of environmental problems influences attitudes toward pro-environmental behavior and increases the likelihood of the adoption of such behaviors [8]. Promoting environmentally friendly attitudes through social influence and demonstrating social acceptance can enhance the motivation to adopt eco-friendly behavior.

Building on previous research that focused on the level of awareness and severity of climate change [9], this study hypothesizes that perceived severity in terms of beliefs leads to pro-environmental behavior and that differences exist in behavior between individuals who recognize the severity of the climate crisis and those who do not. It highlights behavioral differences between these groups. According to VBN theory, individuals who perceive the climate crisis as serious are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior if their values (e.g., biosphere values or altruism) align with sustainability. While previous studies concentrated on perceived severity, the present study examines recipients’ perceptions of the severity of the climate crisis from various aspects based on psychological distance theory.

Psychological distance theory provides a framework for understanding why individuals frequently perceive the climate crisis as a distant problem, which influences the motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior. Psychological distance from climate change is related to pro-environmental behavior [14]. This concept is central to construal level theory [18], which posits that individuals mentally represent events based on perceived distance across four dimensions, namely temporal, spatial, social, and virtual.

First, temporal distance leads to the perception of climate change as a problem in the distant future, with its effects expected to occur decades later. Regarding spatial distance, individuals typically believe that climate change will primarily affect distant places instead of their country. Social distance promotes the view of climate change as a problem that affects other groups except for oneself, which can diminish personal responsibility and empathy [19]. Virtual distance is a psychological perception that leads to the view of climate change.

When a problem is perceived as psychologically distant (high-level construal), individuals tend to think abstractly and focus on the why (e.g., climate change is a global issue). This abstract thinking can reduce the perceived relevance of pro-environmental actions. When the problem is psychologically close (low-level construal), individuals think more specifically and focus on the how (e.g., taking concrete actions such as recycling). This specific way of thinking promotes pro-environmental behavior. Reducing psychological distance increases risk perception and personal relevance, both of which are important predictors of environmental protection behavior [20].

Based on previous research, this study focuses on temporal, social, and virtual distance in terms of psychological distance and examines the relationship between these perceptions and pro-environmental behavior.

H1a–c:

Perception of the severity of the climate crisis ([a] distance, [b] social, and [c] virtual distance) will positively affect pro-environmental behavior.

2.4. Cognitive Seriousness of Climate Crisis-Related Media Reports

The media plays a crucial role in the formation of public perceptions and attitudes by determining which issues receive attention [21]. As a major intermediary between scientific knowledge and public understanding, the media influences how individuals and society recognize the urgency and relevance of climate change. The media not only selects which topics to cover but also influences the public’s interpretation of information by framing environmental problems in particular ways [22]. By emphasizing certain aspects and downplaying others, the media shapes perception and emotional response, thus acting as a cognitive framework that guides individuals in understanding and evaluating complex phenomena such as the climate crisis.

Framing theory highlights that the emphasis of the media on potential dangers or benefits can increase or decrease the intention to engage in specific behaviors [23]. Environmental frames that emphasize long-term damages due to climate change can highlight its importance and severity. Feldman and Hart [4] underscored the significance of framing in climate change communication by analyzing the influence of message design on perceptions and behavioral intentions regarding climate change [23]. The findings suggested that an environmental frame that focuses on ecological impacts (e.g., biodiversity loss and habitat destruction) was not significantly more effective than other frames (e.g., economic or health) in raising awareness about the severity of climate change. In other words, environmental messages alone may not be sufficient for changing attitudes or increasing the perceived seriousness of climate change, especially among audiences previously exposed to similar content.

Media frames play an important role in forming public perceptions and actions on environmental issues [24], economic frames, moral frames, environmental and biological frames, and public health frames [25]. Economic frames can prevent eco-friendly behavior by emphasizing economic losses to individuals. Moral frames can promote eco-friendly behavior by causing responsibility and guilt. Public health frames can affect the introduction of policies that reduce individual and companies’ carbon emissions by connecting with individual health.

This indicates that respondents have likely previously encountered climate-related messages, and their perception of the severity of the climate crisis was not notably affected by whether the message was framed around environmental, economic, or health concerns. Emphasizing the interpretation of climate news based on prior attitudes and values, Nisbett [24] stressed the importance of framing in enhancing the effectiveness of climate change communication. The effects of specific frames are dependent on public values, political tendencies, and prior knowledge. Previous scholars demonstrated that environmental framing is particularly impactful in such contexts.

Media reports on the climate crisis can be exaggerated, factual, or reduced. Exaggerated portrayals may lead to anxiety or helplessness, whereas accurate reports enable informed decision-making. When the crisis is downplayed, it can lead to disengagement, indifference, or resentment toward environmental advocates, as audiences may view them as alarmists.

This study stands apart in that it considers individual perceptions of media reports on the climate crisis. While the actual framing of media coverage is important, individual judgment about the severity of these reports also influences eco-friendly behavior.

H2:

The perceived seriousness of media reports on the climate crisis will positively influence eco-friendly behavior.

2.5. Emotional Factors That Affect Eco-Friendly Behavior: Guilt

This study focuses on guilt as a motivation for environmentally friendly behavior, particularly in comparison with other emotions such as anger and fear, as discussed in the climate crisis research conducted by Mallett and Melchiori [25]. Their analysis highlights the role of guilt and message framing in influencing public support for environmental policies. The authors found that guilt-inducing messages were more effective in increasing public support for environmental bills compared with neutral messages, as guilt motivated participants adopt a more responsible stance on environmental protection.

Self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000) [26] emphasizes the importance of internal motivations, such as guilt and pride, in shaping behavior. According to this theory, feelings of guilt and shame related to nonenvironmentally friendly behaviors promote social responsibility and motivate individuals to adopt eco-friendly practices [26]. As suggested by Bamberg and Moser (2007), guilt as a result of environmental destruction can foster self-control and encourage sustainable practices, while pride associated with eco-friendly actions can reinforce such behavior [27].

An emotional response to one’s perceived responsibility for environmental harm, guilt plays a significant role in motivating pro-environmental behavior. The guilt hypothesis proposes that individuals act to alleviate guilt by engaging in behaviors that are linked to environmental protection [28]. This emotional appeal is further supported the appraisal theory of emotion (Lazarus, 1991) [29], which posits that guilt arises when individuals perceive their actions as harmful and recognize their responsibility for such actions. This emotional state can prompt individuals to adopt compensatory strategies, including eco-friendly behaviors, to address their perceived wrongdoing [4]. Recognizing the negative outcomes of one’s actions and feeling personally responsible trigger guilt, which encourages prosocial behavior aligned with personal norms [30].

H3:

Guilt related to the climate crisis will positively affect eco-friendly behavior.

2.6. Interpersonal Communication and Its Role in Environmental Behavior

2.6.1. Information Seeking

Personal communication behaviors, such as information seeking and interpersonal communication, are vital in addressing the climate crisis by influencing awareness, attitudes, and behaviors, which are connected to eco-friendly actions through the psychological, social, and cognitive pathways.

According to the TPB (Ajzen, 1991), the pursuit of information increases awareness, attitude formation, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control over environmental issues, which directly predict pro-environmental behavior [8]. Individuals actively seek information related to the climate crisis to fulfill specific needs such as understanding its causes and impacts. In this context, information seeking facilitates the development of environmental understanding, which is a fundamental element of decision-making and behavior change based on acquired information. Therefore, individuals who actively seek information are more likely to adopt eco-friendly behaviors [31].

2.6.2. Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication plays a crucial role in shaping environmental behavior by spreading norms, values, and behaviors through social networks. For example, discussing climate issues with colleagues and family can normalize green practices and promote collective action. These conversations help foster behavioral change by strengthening personal responsibility and making climate issues feel immediate and relevant.

According to social influence theory, interpersonal communication promotes the spread of norms, values, and behaviors within social networks [32]. Through conversations about climate issues within social circles, individuals contribute to collective action against climate change by challenging unsustainable norms and promoting pro-environmental behaviors.

Communication behaviors, such as individual information seeking and interpersonal communication, can create positive feedback, including raising awareness of climate policies and strengthening public support for systemic change. Interpersonal discussions can amplify individual responsibility and motivate behavioral change by making climate issues feel more urgent and relevant. Sharing experiences and strategies also promotes social learning, which makes pro-environmental behavior more accessible and acceptable.

Interpersonal communication enables individuals to exchange information, discuss concerns, and influence one another’s perceptions of environmental issues. These interactions can further enhance awareness and increase the adoption of environmentally friendly behaviors.

In summary, recognizing the seriousness of media coverage and engaging in interpersonal communication are crucial for promoting pro-environmental behavior. Media informs and structures discourses, while personal communication reinforces messages, which makes climate issues feel immediate and relevant. Shared emotions, such as guilt or hope, help spread pro-environmental norms and encourage action.

H4a,b:

Climate crisis-related communication behavior ([a] information seeking and [b] interpersonal communication) will positively affect pro-environmental behavior.

2.7. Climate Crisis Communication Prediction Forecasts

In the relationship between temporal distance and information seeking, recognizing that temporal distance is long can reduce the need for information seeking about climate change. The reason is that results may seem distant and not immediate [33]. When people perceive the climate crisis as an event that will occur in the distant future (i.e., with a large temporal distance), then they are less likely to engage in interpersonal discussions [18]. Social distance refers to the perceived closeness or similarity between oneself and others affected by climate change; empathy and concern increase with the increase in social distance. In relation to information seeking, individuals with low levels of social distance (e.g., feeling connected to people affected by climate change) are more likely to seek information to understand and address the problem [34].

In the case of interpersonal communication, closer social ties or decreased social distance may motivate discussions on the climate crisis, in particular, sharing concerns or solutions [20]. Perceived severity of media coverage refers to one’s judgment of how alarming or serious the media portrays the climate crisis. The higher the perceived severity, the more likely an individual will be to seek more information to understand risks and take actions [33].

Guilt occurs when individuals feel responsible for contributing to climate change or failing to sufficiently act to address it. Guilt can be a powerful motivator of communicative behavior. Regarding information seeking, guilt can lead individuals to seek information as a means of reducing cognitive dissonance and mitigating their contribution to the crisis [35]. Guilt can also lead to discussions with colleagues as a way of expressing concerns, sharing knowledge, and motivating collective action [26,35].

2.8. Communication as a Control Variable

This study examined the moderating effect of communication behavior on the relationship between the perceived severity of the climate crisis, emotions, and environmentally friendly behavior. According to the TPB, information seeking increases knowledge and shapes attitudes, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control, which are predictors of behavior [8]. When individuals feel guilty about the climate crisis or perceive it as severe, active information seeking helps bridge the gap between emotional reactions and informed action by providing factual knowledge or actionable solutions. This process strengthens the association between perceived severity or guilt and pro-environmental behavior.

The risk information seeking and processing model (Griffin et al., 1999) states that individuals seek information based on their perception of risk and uncertainty [36]. When the climate crisis is perceived as severe, individuals who actively seek information are more likely to take informed action (e.g., save energy and reduce waste). This moderating effect occurs because information seeking reduces uncertainty and provides clarity about actionable steps, thereby reinforcing the perceived need for environmentally friendly behavior.

Regarding the moderating effect of interpersonal communication, social influence theory (Bandura, 1991) states that interpersonal communication promotes the spread of norms, attitudes, and behaviors [37]. Discussing the severity of the climate crisis or the guilt associated with environmental harm with others can normalize pro-environmental practices and amplify the emotional intensity of the issue. Discussing environmental issues with others increases awareness, reinforces norms, and increases the likelihood of environmentally friendly behavior [38].

2.9. Eco-Friendly Behavioral Preceding Variable

2.9.1. Demographic Factors

Among the demographic factors, gender and age consistently predict environmentally friendly behavior. Previous studies have demonstrated that women tend to exhibit stronger environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors than men, potentially due to their higher levels of environmental concern and empathy [39]. Age influences behavior differently: older individuals may favor practices such as energy conservation, which are frequently rooted in long-standing habits, while younger individuals may be more receptive to the adoption of new eco-friendly behaviors, such as using public transportation [40].

2.9.2. Environmental Concern

In this study, the interest in the environment is assumed to be a prior factor because it is the basis for forming individual attitudes, intentions, and actions in eco-friendly practices. Environmental interests, defined by individual interest in environmental issues, are an important motivational driver of eco-friendly behavior. The VBN theory assumes that individuals with stronger biological values and those that believe in ecological damage are likely to adopt eco-friendly norms that lead to eco-friendly actions [14]. Interest in the environment originates from altruistic values, and interest in environmental issues emphasizes the dangers of deterioration and belief in individual responsibilities. Norms are activated, and individuals act in an environmentally friendly manner. Those who are interested in environmental issues are likely to be an environmentally conscious person and integrate this identity into their concepts [41,42].

2.9.3. Political Tendency

Political tendencies are closely correlated with environmental attitudes, in which progressive individuals typically display greater interest in climate change and participate more actively in environmental protection activities compared with conservatives [43]. Ideology influences behavioral intentions by shaping the sense of responsibility and the need for collective action.

Moral foundations theory (Haidt, 2007) suggests that differences in moral priorities influence the perceptions of issues. Progressive individuals tend to prioritize environmental protection based on the moral foundations of harm and care [43]. Similarly, the norm activation model (Schwartz, 1977) argues that personal norms, activated by awareness of consequences and a sense of responsibility, predict environmentally friendly behavior [31].

Progressive individuals are more likely to experience guilt or the moral obligation to act on climate issues due to their openness to information on anthropogenic climate change. Conversely, conservatives may view climate change as exaggerated or caused by external factors (e.g., natural cycles or actions by foreign countries), which can reduce feelings of guilt or responsibility.

From the perspective of value systems and moral foundations, progressives are more likely to perceive climate change as a moral issue, which prompts them to engage in behaviors such as recycling, reducing energy consumption, and supporting climate policies [41,44]. Conversely, conservatives may exhibit skepticism toward environmental policies, particularly when these policies are perceived as threats to economic stability, individual freedom, or traditional structures.

2.10. Research Framework: Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study examines the psychological and communication factors influencing eco-friendly behavior. Specifically, it explores how awareness of the climate crisis, media framing, and emotions (such as guilt) shape communication behaviors (e.g., information seeking and interpersonal communication) and pro-environmental actions. The key research questions (RQ) and hypotheses (H) are as follows.

RQ 1. What are the factors that influence climate crisis-related communication behavior (e.g., additional information exploration and interpersonal communication)?

RQ 1-1. How does the preliminary void (sex, age, political tendency, and environmental interest) influence communication behavior?

RQ 1-2. Cognitive seriousness; how do time and social distance influence communication behavior?

RQ 1-3. How does the seriousness of media reports affect communication behavior?

RQ 1-4. How do emotions affect communication behavior?

RQ2. What are the factors that influence eco-friendly behaviors related to climate crisis ([a] purchase, [b] public transportation, and [C] energy saving)?

RQ 2-1. How does the preliminary void (sex, age, political tendency, environmental interest) affect eco-friendly behavior?

RQ 2-2. How did the recognized severity (time and social distance) affect eco-friendly behavior?

H1:

The severity of the climate crisis ([a] time, [b] social, and [c] virtual distance) will exert a positive effect on eco-friendly behavior.

RQ 2-3. How does the severity of media reports influence eco-friendly behavior?

H2:

The severity of media reports related to the climate crisis will positively influence eco-friendly behavior.

RQ 2-4. How does emotion (guilt) affect eco-friendly behavior?

H3:

Guilt about the climate crisis will positively affect eco-friendly behavior.

RQ 2-5. How does communication acts ([a] additional information search and [B] interpersonal communication) affect eco-friendly behavior?

H4:

Communication behavior related to climate crisis ([a] additional information exploration and [b] interpersonal communications) will positively affect eco-friendly behavior.

RQ 3. Communications ([a] additional information search and [b] interpersonal communication) will exert a regulatory effect in the relationship between recognized severity and eco-friendly behavior related to climate change.

2.11. Research Model

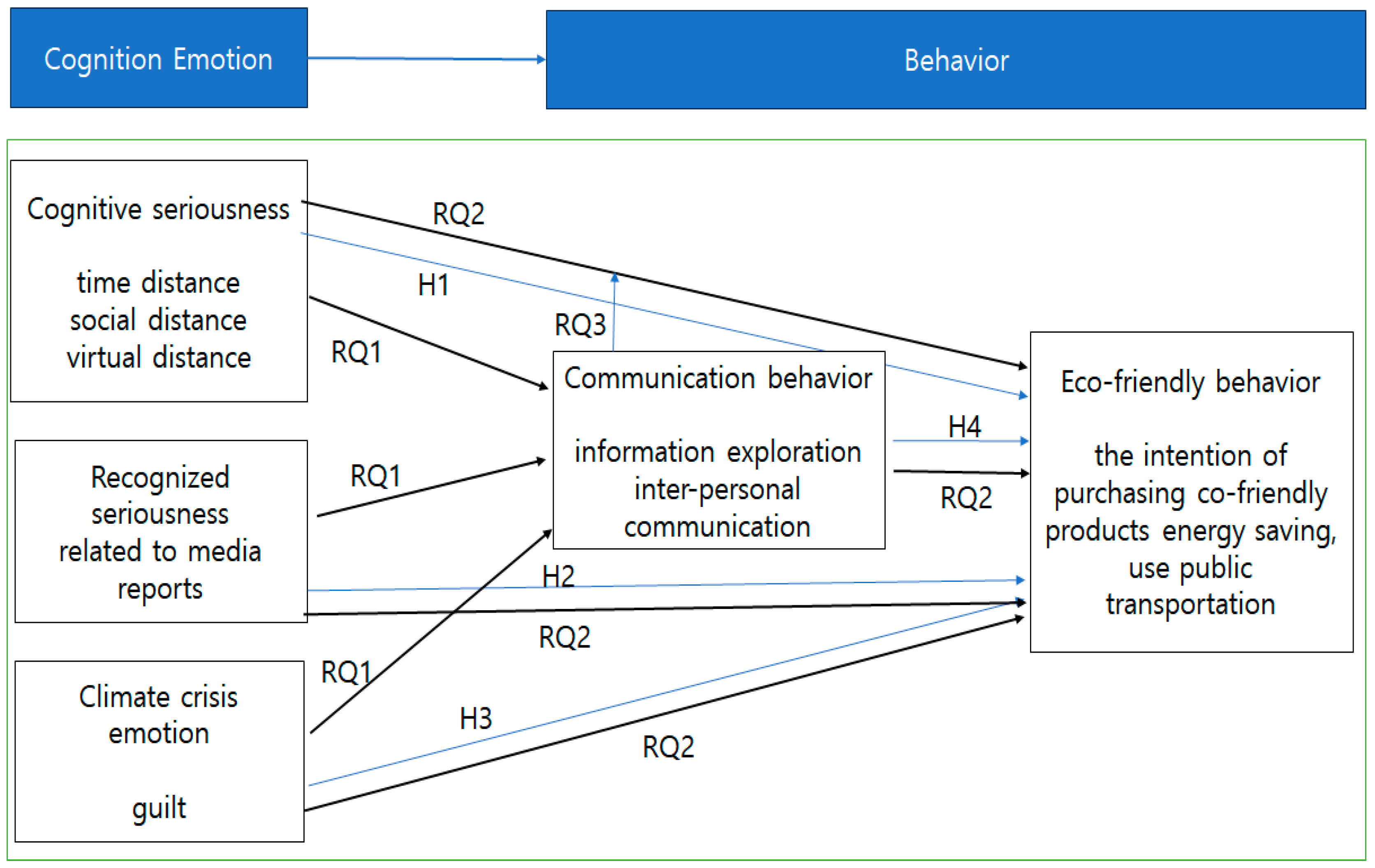

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among cognition, emotion, and behavior. For RQ 1, individuals seek and discuss information when perceiving the climate crisis or media reports as severe or feeling guilt. RQ 2 explores the impact of severity, media, guilt, and communication behavior on eco-friendly actions. Communication behavior acts as a mediator and an amplifier, connecting perceptions and emotions to behaviors. The model highlights how perceived seriousness and guilt can directly or indirectly drive eco-friendly behavior through enhanced communication, which boosts participation in sustainable practices.

Figure 1.

Model of predictors of pro-environmental behavior.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis Target

This study utilizes data from the National Environmental Awareness Survey, an annual survey conducted by the Korea Environment Institute (KEI), which aims to assess public perceptions of environmental issues. The survey was administered online to a sample of 3088 respondents, who participated via mobile phones or personal computers through a web-based questionnaire. The questionnaire, based on the 2021 revised version, includes four primary sections: environmental awareness, environmental attitudes and practices, environmental demands, and environmental policies, with additional items introduced to address emerging environmental concerns.

Hierarchical regression analysis was employed to explore the relationships between environmental awareness, emotions, and eco-friendly behaviors, with a focus on testing the moderating role of communication behaviors such as information seeking and interpersonal communication. By sequentially entering independent variables, hierarchical regression allows for the assessment of the incremental explanatory power of each predictor and controls for potential confounding factors. This methodology is particularly well-suited for identifying causal relationships and understanding the complex, sequential influences of cognitive and emotional factors on environmental behaviors.

The Environmental Awareness Survey reorganizes question codes, content, and scales. An online survey was conducted with 3088 adults (aged 19–69 years) nationwide using proportional allocation by region, gender, and age. The survey was conducted by a professional company and lasted 8 days (21–28 September 2023).

3.2. Operational Definition and Measurement of Variables

3.2.1. Psychological Distance: Temporal, Social, and Virtual Distance

Psychological distances related to climate change were identified based on prior studies, including temporal, social, and virtual distance [19]. Temporal distance was measured using the question, “Do you think our country will be negatively affected by climate change?” The options were: “It will not be affected at all” (1 point), “It will not be affected within 100 years” (2 points), “It will be affected within 50 years” (3 points), “It will be affected within 20 years” (4 points), and “It will be affected within 10 years” (5 points).

The study assessed social distance using the question, “How serious an impact does you think climate change has had on society?” Virtual distance was measured by asking, “How serious an impact do you think climate change has had on you?” Social and virtual distances were measured using a five-point scale (5 = very serious, temporal distance [mean = 1.74, SD = 1.10], social distance [mean= 4.12, SD = 0.66], and virtual distance [mean = 3.63, SD = 0.74]).

3.2.2. Recognized Seriousness of Media Reports

The recognized seriousness of media reports was assessed using the item, “How do you think that you are dealing with environmental and environmental issues in the media?” (5 = media reduces the seriousness, 1 = media exaggerates the seriousness), A score of 5 means that the seriousness of the environmental problem is overly reduced (mean = 2.97, SD = 0.89).

3.2.3. Guilt

Guilt was measured by asking participants to indicate the extent to which they agree with the statement, “I sometimes engage in harmful actions and feel guilty”, using a five-point scale (5 = strongly agree, mean = 3.26, SD = 0.91).

3.3. Adjustable Variables

3.3.1. Communication Behavior

Additional information about information seeking was measured by rating the item “I try to obtain more information about the environment” using a five-point scale (mean = 3.31, SD = 0.76). Interpersonal communication was measured using a five-point scale by asking, “I talk to people around me about new facts I learned about the environment” (mean = 3.24, SD = 0.83). A score of 5 means strongly agree.

3.3.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior

Pro-environmental behavior was examined using items on the intention to purchase eco-friendly products (“I consider purchasing products with eco-friendly or recycling marks first”), use public transportation (“I use eco-friendly transportation (walking, bicycle, public transport) when traveling short distances”), and energy saving (I use water and electricity sparingly to reduce water and electricity bills at my house) rated on a five-point scale (5 = strongly agree). The results are as follows: intention to purchase eco-friendly products: mean = 3.14, SD = 0.91; using public transportation: mean = 3.67, SD = 1.05; and energy saving: mean= 3.87, SD= 0.87.

3.4. Antecedent Variable

Gender, age, interest in environmental issues, and political inclination were assumed to be the antecedent variables that influence eco-friendly behavior.

Interest in environmental issues was assessed using the item “How interested are you in environmental issues on a daily basis?” rated on a five-point scale (5 = very interested; mean = 3.79, SD = 0.76).

Political inclination was measured by asking, “To what extent do you consider yourself politically progressive or conservative?” and was assessed using a five-point scale (1 = very liberal, 5 = very conservative, mean = 3.16, SD = 1.13).

3.5. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression analysis was used to examine the predictors of eco-friendly behaviors through six blocks: demographics (gender, age, environmental interest, and political tendency), psychological distance (time, social, and virtual), severity of media reports, emotions (guilt), communication behaviors (information seeking and interpersonal communication), and eco-friendly behaviors (product purchase, public transportation use, and energy saving).

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis Between the Major Variables

Table 1 presents the results of the correlation analysis among guilt, seriousness, and social distance with the variables information seeking, interpersonal communication, and environmentally friendly behavior. The study observed that environmentally friendly behavior (e.g., energy saving and use of public transportation) is interconnected with these psychological and emotional factors.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix of major variables (N = 3088).

The severity of climate crisis-related reports was correlated with virtual (0.1653 *) and social (0.2043 *) distance. The greater the recognized severity, the closer people feel at this level. The weak negative correlation with temporal distance (−0.1127 *) indicates that perceived severity slightly decreases temporal distance. Cognitive seriousness exhibited a positive, moderate correlation with guilt (0.1157 *) and additional information seeking (0.1467 *). In other words, the higher the severity of cognitive seriousness, the more the guilt, and the exploration of additional information tend to increase slightly.

Guilt displayed a positive correlation with the variables virtual distance (0.1556 *), social distance (0.1525 *), additional information seeking (0.2357 *), and interpersonal communication (0.2013 *). This result indicates that guilt motivates participation in additional information seeking and interpersonal communication. Guilt was also positively correlated with the intention to purchase eco-friendly products (0.3086 *).

Additional information seeking was strongly correlated with interpersonal communication (0.5645 *). This finding indicates that individuals who seek more information are more likely to discuss it with others. Additional information seeking also pointed to a certain degree of correlation with environmentally friendly behaviors such as energy saving (0.2899 *) and public transportation (0.1852 *).

Regarding eco-friendly behavior, energy saving displays positive correlations with all variables, but has a particularly strong relationship with public transportation (0.3959 *), which implies that individuals who engage in one environmentally friendly behavior are likely to participate in others as well. Other notable correlations included social distance (0.1894 *) and additional information seeking (0.2899 *). The use of public transportation is correlated with additional information seeking (0.1852 *) and energy saving (0.3959 *), thus reflecting patterns of participation in eco-friendly behaviors. Purchase intentions exhibit a positive relationship with guilt (0.3086 *) and the pursuit of additional information (0.3422 *), which indicates that emotional and cognitive factors influence consumer behavior.

In general, correlation coefficients above 0.5 in social science research may suggest a strong relationship, but it is necessary to apply more quantitative criteria to determine multicollinearity. Therefore, this study further examined the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The results showed that all variables had VIF values of 3.0 or less, indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern.

4.2. RQ 1: Hierarchical Regression Analysis of Communication Predictions

The first stage included preceding variables such as performance age, environmental interest, and political tendency; in the second stage, the recognized serious variables were added. In the third stage, the recognized severe variable for media reports was added. In the fourth stage, guilt, an emotional variable, was added. Table 2 presents the results of the analysis of the prediction variable of information exploration and interpersonal communication behavior.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analysis of predictors of communication behavior.

The final model describes the difference in information exploration of 22% and 16% of interpersonal communication. The results indicate that emotional factors (e.g., guilt) and environmental interest play an important role in predicting this behavior. Specifically, the results of the hierarchical regression analysis on Block 1 are an important predicting variable for both behaviors (information search: β = 0.39, interpersonal communication: β = 0.37, both ps < 0.001). Gender (female) exerts a small but significant positive impact, especially on interpersonal communication (β = 0.13, p < 0.001). Political ideology exhibits a negative connection (information exploration: β = −0.03, p < 0.001, interpersonal communication: −0.04, p < 0.001). The impact on the individual in terms of the perception of the impact of Block 2 climate crisis positively predicted both behaviors (β = 0.19, p < 0.01 for information search = 0.15, p < 0.001). The severity of Block 3 (media reports) exerted positive impacts on information search (β = 0.06, p < 0.001) and interpersonal communication (β = 0.05, p < 0.001). Block 4 stands for guilt, which strongly predicted the two behaviors (β = 0.13, p < 0.001 for information exploration, β = 0.11, p < 0.001).

4.3. Eco-Friendly Behavior Prediction Variable Hypothesis and Results of Analysis for RQ 2

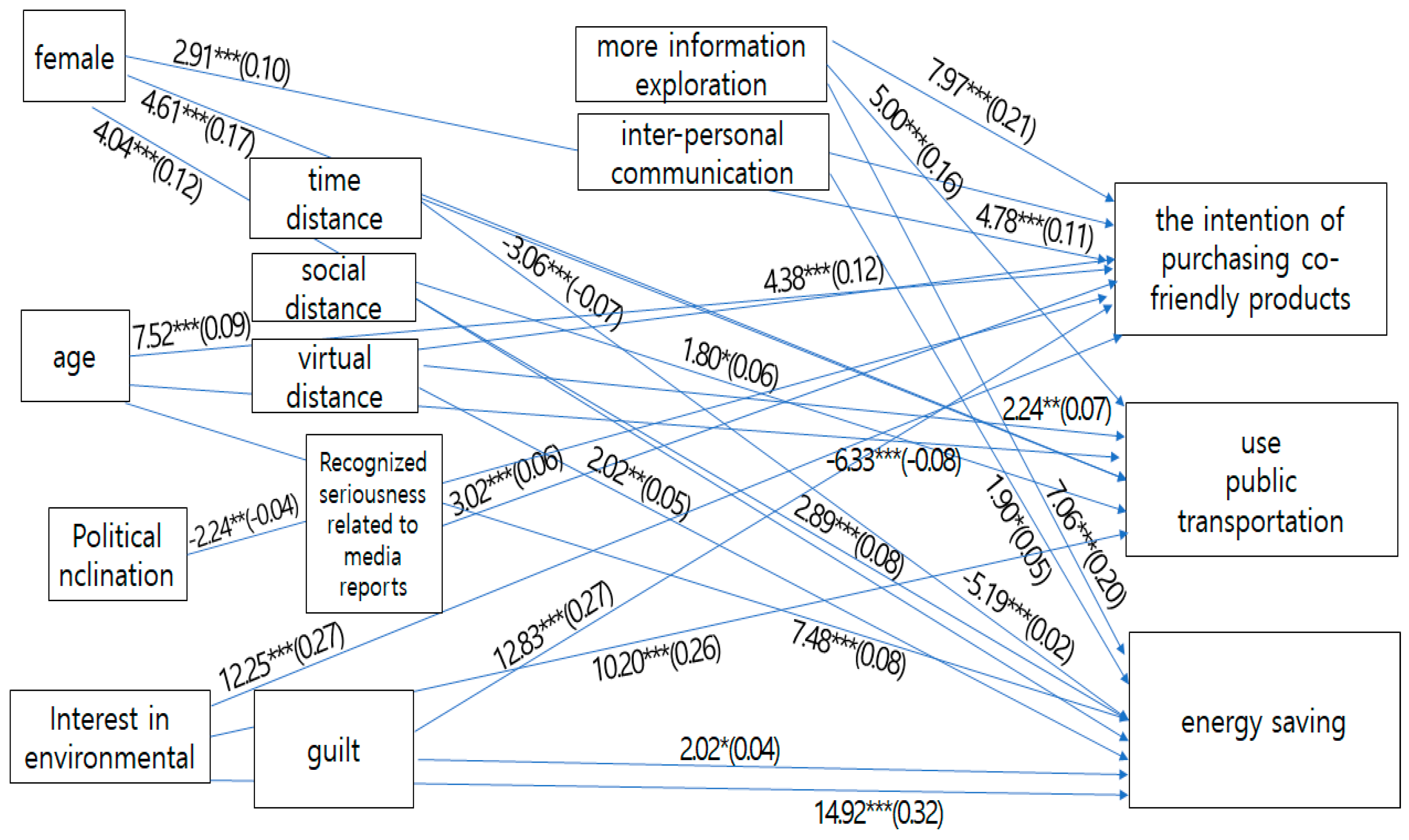

This study explored the predictors of eco-friendly behavior and focused on psychological distance, media framing, guilt, and communication behavior. It analyzed the impact of demographics, perceived severity of the climate crisis, media coverage, emotions, and communication on three pro-environmental behaviors, namely purchase intention, transportation, and energy saving. Table 3 shows the results of hierarchical regression analysis by dividing eco-friendly behavioral predictions into five blocks. The analysis results were presented as follows.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analysis of predictors of pro-environmental behavior.

In the hierarchical regression model, demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, environmental interest, and political orientation) were included in the first step, followed by perceived severity in the second step, severity of media coverage in the third, guilt in the fourth, and communication behavior in the fifth. The final model explained 22% of purchase intention, 8% of public transportation use, and 17% of energy saving. Information seeking and environmental concerns emerged as consistent predictors across all behaviors.

H1 (temporal distance) was partially supported, as it positively predicted public transportation use (β = −0.07, p < 0.001) and energy saving (β = −0.10, p < 0.001) but not purchase intention. H2 (social distance) was also partially supported, as it positively predicted public transportation use (β = 0.08, p < 0.001) and energy saving (β = 0.06, p < 0.001) but not purchase intention. H3 (virtual distance) was fully supported, as it positively predicted purchase intention (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), public transportation use (β = 0.07, p < 0.05), and energy saving (β = 0.05, p < 0.05). H4 (perceived severity of media coverage) was partially supported, because it positively influenced purchase intention (β = 0.06, p < 0.001) but not the other behaviors. H5 (guilt) was partially supported, significantly predicting purchase intention (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) and energy saving (β = 0.04, p < 0.05) but not the use of public transportation.

Block 1 (demographics) demonstrated that women and those with high levels of environmental concerns engaged more in eco-friendly behaviors. Younger people preferred public transportation, while older individuals focused on energy saving and eco-friendly products. Block 2 (perception of impact) affected all behaviors, while Block 3 (media coverage) influenced purchase intention. Guilt (Block 4) strongly predicted purchase intention. Block 5 (communication behavior) significantly influenced all behaviors with information seeking and interpersonal communication enhancing purchase intention and energy saving.

These findings highlight the importance of demographic factors, emotional appeals, and communication strategies in promoting eco-friendly behaviors.

Figure 2 illustrates the values presented in Table 1, focusing on the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. By incrementally incorporating an eco-friendly rinse-based predictor variable, the figure presents the results of a hierarchical regression analysis used to assess the contribution of the independent variables. A positive coefficient indicates that the dependent variable increases as the independent variable increases, whereas a negative coefficient signifies that the dependent variable decreases as the independent variable increases.

Figure 2.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis. Note. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

4.4. Results of the Analysis of Eco-Friendly Behavioral Control for RQ 3

Interpersonal communication exerted a positive influence on the relationship between virtual distance and environmentally friendly behavior (energy saving). It also exerted a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the temporal distance and energy conservation. Table 4 presents the results of the analysis of the moderating effect of communication behavior on the relationship between perceived seriousness and eco-friendly behavior.

Table 4.

Moderating effect of communication behavior on relationship between perceived severity and pro-environmental behavior.

The relationship between virtual distance and energy saving displayed a negative but statistically nonsignificant direct effect (coefficient = −0.0914, p = 0.226). This result indicates that virtual distance alone does not exert a significant direct impact on energy saving behavior. Similarly, interpersonal communication exerted a negative but nonsignificant direct effect (coefficient = −0.0626, p = 0.455). However, when virtual distance interacted with interpersonal communication (coefficient = 0.0726, p = 0.001), the interaction effect was positive and statistically significant. This finding implies that interpersonal communication moderates the effect of virtual distance on energy conservation, which amplifies its positive impact.

The direct effect of temporal distance on the use of public transportation was negative and statistically significant (coefficient = −0.2971, p = 0.002). This result denotes that the likelihood of using public transportation decreases with the increase in the perceived temporal distance of eco-friendly behavior. Conversely, interpersonal communication exerted a significant and positive direct effect (coefficient = 0.2093, p = 0.007), which indicates that it encourages the use of public transportation. Furthermore, the effect of the interaction between temporal distance and interpersonal communication (coefficient = 0.0489, p = 0.042) was positive and statistically significant. This result indicates that interpersonal communication mitigates the negative impact of temporal distance on the use of public transportation.

5. Discussion

This study examined the predictors of communication behavior, particularly information seeking and interpersonal communication, in the context of the climate crisis. It performed hierarchical regression analysis to analyze individual and situational factors, including demographics, environmental concerns, perceived severity, and guilt.

The perceived severity of the climate crisis strongly predicted information seeking and interpersonal communication with women more engaged in discussions. Conservative political tendencies hindered these behaviors, which indicates the need for targeted strategies. Perceptions of psychological distance decreased the adoption of eco-friendly behavior, which emphasizes the importance of local and immediate impacts. Media coverage enhanced communication, while guilt motivated information seeking as a coping mechanism. Women exhibited higher levels of participation in pro-environmental behaviors, while younger individuals favored the use of public transportation and older ones prioritized energy conservation and eco-friendly products. Environmental concern was the strongest predictor wherein practical benefits influence purchase decisions more than perceived distances.

Guilt strongly predicted purchase intentions but exerted limited effects on other behaviors, thus highlighting the need for complementary strategies. Information seeking was a key predictor across behaviors, while interpersonal communication significantly influenced purchase intention and energy conservation. It also moderated psychological distances, thus bridging the gap between immediate actions and long-term climate benefits. Guilt can serve as a strong motivator for immediate eco-friendly behavior, but it is unlikely to sustain long-term behavioral change unless reinforced by positive emotions such as pride or self-efficacy [30]. Excessive guilt may lead to anxiety, stress, or feelings of helplessness, which can hinder eco-friendly actions [36]. This study highlights guilt as a significant predictor of eco-friendly behavior but emphasizes the need for a balance between guilt and other motivational factors, such as pride, to maintain long-term engagement in sustainable practices.

This study builds on previous research that links proximity to environmental issues, such as climate change, to stronger eco-friendly behavior. It demonstrates that perceptions of the climate crisis’ severity, influenced by psychological distance, motivate individuals to seek information and engage in environmentally responsible actions. Media coverage of the climate crisis plays a pivotal role in promoting such behaviors by fostering information seeking and interpersonal communication, aligning with theories that media reports shape public interest and inspire action.

The study also reinforces the theory that guilt is a powerful motivator for eco-friendly behavior. Negative emotions, particularly guilt, have been shown to strongly predict information seeking and eco-friendly purchasing intentions, highlighting the effectiveness of emotion-based messaging in promoting environmental action.

Demographic differences were observed in communication preferences and eco-friendly behaviors, with women and younger individuals favoring interpersonal communication and public transportation, while older individuals focused more on energy conservation and eco-friendly purchases. This suggests that communication preferences and behaviors may not align with existing theoretical models, underscoring the need for tailored strategies that consider demographic factors such as age and gender.

The findings provide valuable insights for stakeholders, including policymakers and environmental communicators. Policymakers can emphasize the immediacy and relevance of climate threats, while environmental communicators can develop messages that resonate emotionally with individuals, tailored to specific demographic groups. Overall, this study advocates for a multifaceted, targeted approach to promoting eco-friendly behavior that accounts for emotional drivers, demographic differences, and media framing.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the effects of cognitive and emotional factors, including psychological distance, media framing, and guilt, on communication and pro-environmental behavior. It emphasizes the reduction of psychological distance through personalized messages and the use of guilt to drive eco-friendly actions, while balancing guilt with positive emotions such as pride for sustaining long-term changes in behavior.

The study highlights guilt as a key emotional driver but suggests the exploration of other emotions such as pride, fear, and anger. It calls for cross-cultural, longitudinal, and norm-based research, as well as investigation into the interaction between online and offline behaviors through digital platforms for further insights.

The current research offers valuable contributions to an enhanced understanding of the relationship among perceptions, emotions, and behaviors in the context of the climate crisis, helping to design other effective communication strategies and policies to encourage sustainable practices.

This study offers valuable insights into the relationship between the climate crisis, guilt, communication behavior, and eco-friendly actions, yet several limitations must be acknowledged. While the study establishes clear correlations, the use of time-series data would provide a more robust understanding of causal relationships and the long-term effects of media framing on eco-friendly behavior. The focus on a specific demographic limits the generalizability of the findings; thus, conducting similar research across diverse cultural and regional contexts would enhance the broader applicability of the results. Additionally, while this study primarily emphasizes guilt as an emotional driver, future research should examine other emotions, such as fear, pride, or shame, as potential motivators of pro-environmental behavior. Finally, investigating the long-term effects of emotions, media frames, and psychological distance on eco-friendly behavior would deepen our understanding of how individual perceptions and behaviors evolve over time, contributing to a more comprehensive view of the sustainability of eco-friendly actions.

In this study, the emotions considered as key predictors of eco-friendly behavior are socially constructed and vary significantly across cultures. The experience of emotions such as guilt, fear, and responsibility in environmental issues is shaped by cultural norms at both the individual and group levels [45]. Additionally, individuals from different cultural backgrounds perceive the psychological distance and risks associated with the climate crisis differently, which in turn influences their emotional engagement and behavioral responses [45].

Therefore, when interpreting and generalizing research findings from a specific region, such as Korea, it is essential to consider cultural differences in emotional responses and the role of media in framing climate issues. These factors may lead to varying perceptions and reactions among different populations, underscoring the importance of cultural context in climate crisis communication and behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.; methodology, J.H. and C.-Y.J.; software, C.-Y.J.; validation, J.H. and C.-Y.J.; formal analysis, C.-Y.J.; data curation, C.-Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study utilized publicly available data that did not contain personally identifiable information, as provided on the Korea Environment Institute (KEI)’s homepage (https://doi.org/10.23160/keidata.12) a government-affiliated organization of South Korea. Data Connection Date: 19 November 2024. According to Chapter 2, Article 6 of the Korea Environment Institute’s Research Ethics Regulations, the Research Ethics Committee is responsible for reviewing and approving research through deliberation and voting on the initiation of preliminary surveys and the approval of research findings (https://www.kei.re.kr/menu.es?mid=a10503000000/https://www.kei.re.kr/board.es?mid=a20609010000&bid=0061).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chang-Young Jeon was employed by the company Korea Press Foundation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Korea. The Environmental Perception of Korean Society Through Big Data Analysis. Available online: https://wwfkorea.or.kr/data/file/korean_report/1794572195_LVUsXNcj_01ba13033992c5a3e94adc9f5dc3ecfcb491a74d.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Environmental Research Institute (KEI). National Environmental Awareness Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.kei.re.kr/elibList.es?mid=a10101010000&elibName=researchreport&class_id=&act=view&c_id=760172 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Li, N.; Su, L.Y. Message Framing and Climate change communication: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Appl. Commun. 2018, 102, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, N.S.; Leach, C.W.; Kessler, T. Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behaviour: Different emotions predict distinct intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, C.W. Climate change information seeking. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovick, S.R.; Bigsby, E.; Wilson, S.R.; Thomas, S. Information seeking behaviors and intentions in response to environmental health risk messages: A test of a reduced risk information seeking model. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xu, J. A comparative study of the role of interpersonal communication, traditional media and social media in pro-environmental behavior: A China-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, W.A. Energy: In Context; Lerner, B.W., Lerner, K.L., Riggs, T., Eds.; World Commission on Environment and Development: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1986; Volume 2, pp. 903–933. Available online: https://go-gale-com-ssl.proxy.kookmin.ac.kr/ps/i.do?v=2.1&u=keris183&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX3627100233&p=GVRL&sw=w&aty=ip (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1965; Available online: http://commres.net/wiki/_media/olson.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleres, J.; Wettergren, Å. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2017, 16, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Hine, D.W.; Marks, A.D. The future is now: Reducing psychological distance to increase public engagement with climate change. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSombre, E.R. Why Good People Do Bad Environmental Things; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.; Druckman, J.N. Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2007, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, M.C. Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2009, 51, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, R.K.; Melchiori, K.J. Guilt and environmental message framing: How guilt impacts public support for environmental legislation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Autonomy is no illusion: Self-determination theory and the empirical study of authenticity, awareness, and will. In Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology; Greenberg, J., Koole, S.L., Pyszczynski, T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 449–479. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232506712 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Weber, E.U.; Markowitz, E.M. The influence of anticipated pride and guilt on pro-environmental decision making. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Stillwell, A.M.; Heatherton, T.F. Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrselja, I.; Pandžić, M.; Rihtarić, M.L.; Ojala, M. Media exposure to climate change information and pro-environmental behavior: The role of climate change risk judgment. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Howe, L.; Walton, G. How social norms are often a barrier to addressing climate change but can be part of the solution. Behav. Public Policy 2021, 5, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, R.K.; Harrison, P.R.; Melchiori, K.J. Guilt and Environmental Behavior. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2622–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environ. Res. 1999, 80 Pt 2, S230–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Dilling, L. Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Balázs, B.; Mónus, F.; Varga, A. Age differences and profiles in pro-environmental behavior and eco-emotions. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2024, 48, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Opotow, S. (Eds.) Clayton, S.; Opotow, S. (Eds.) Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociol. Q. 2011, 52, 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science 2007, 316, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J. A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).