Sustainable Comfort Design in Underground Shopping Malls: A User-Centric Analysis of Spatial Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Step 1: Collection of Quantitative Data Related to User Perception

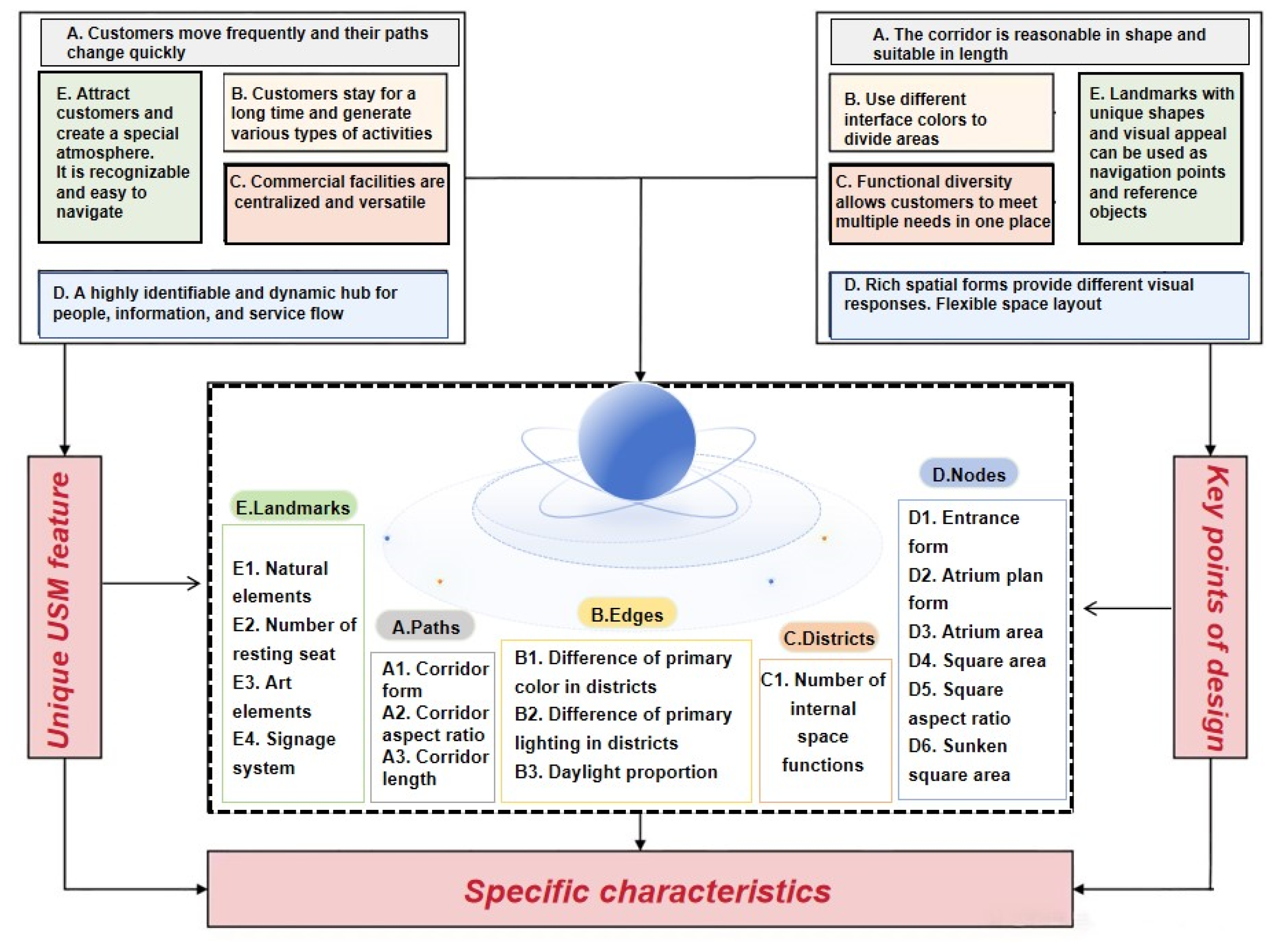

2.2. Step 2: Collection of Quantitative Data Related to Spatial Characteristics

2.3. Step 3: Statistical Analysis

3. Results

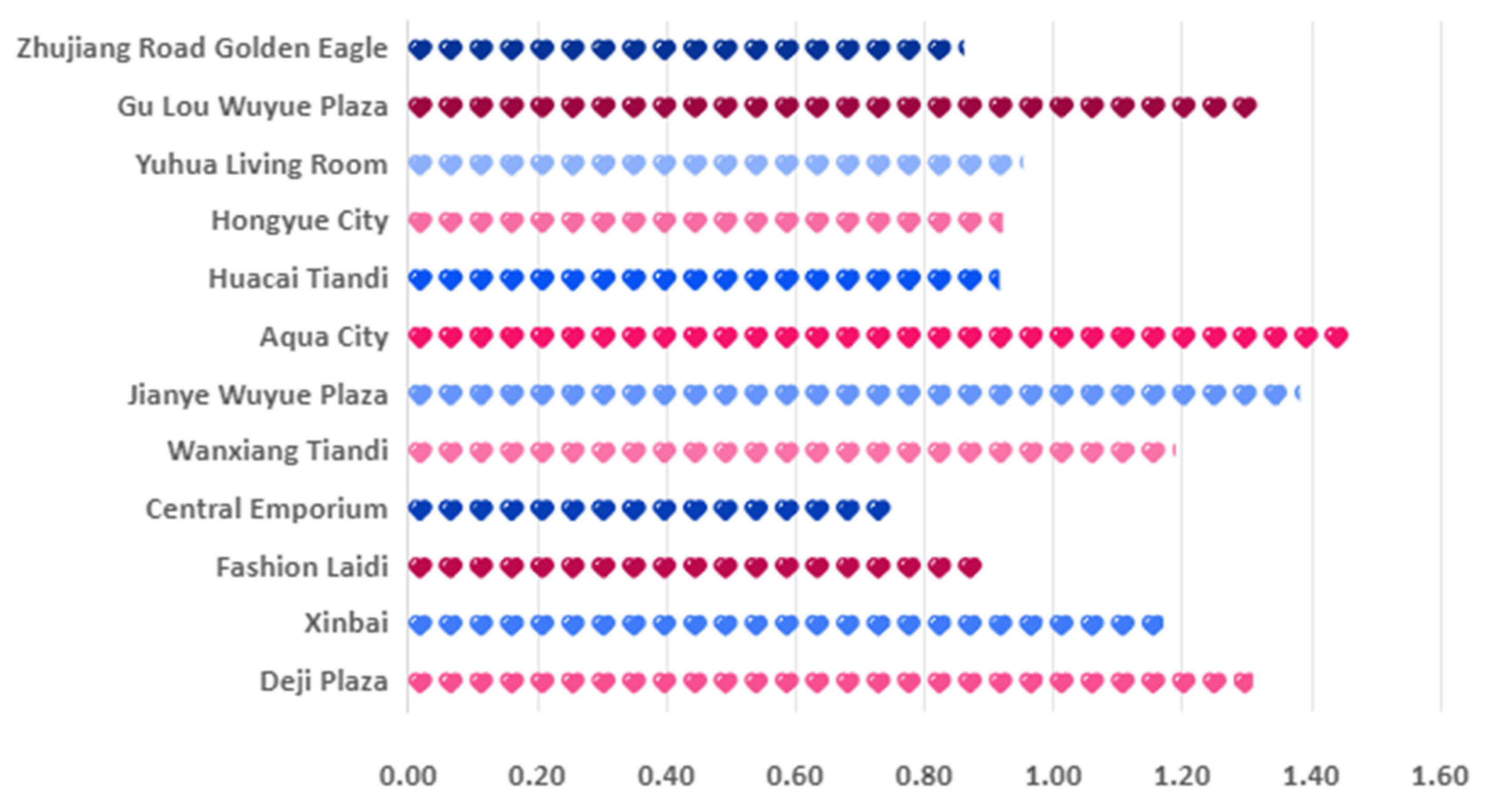

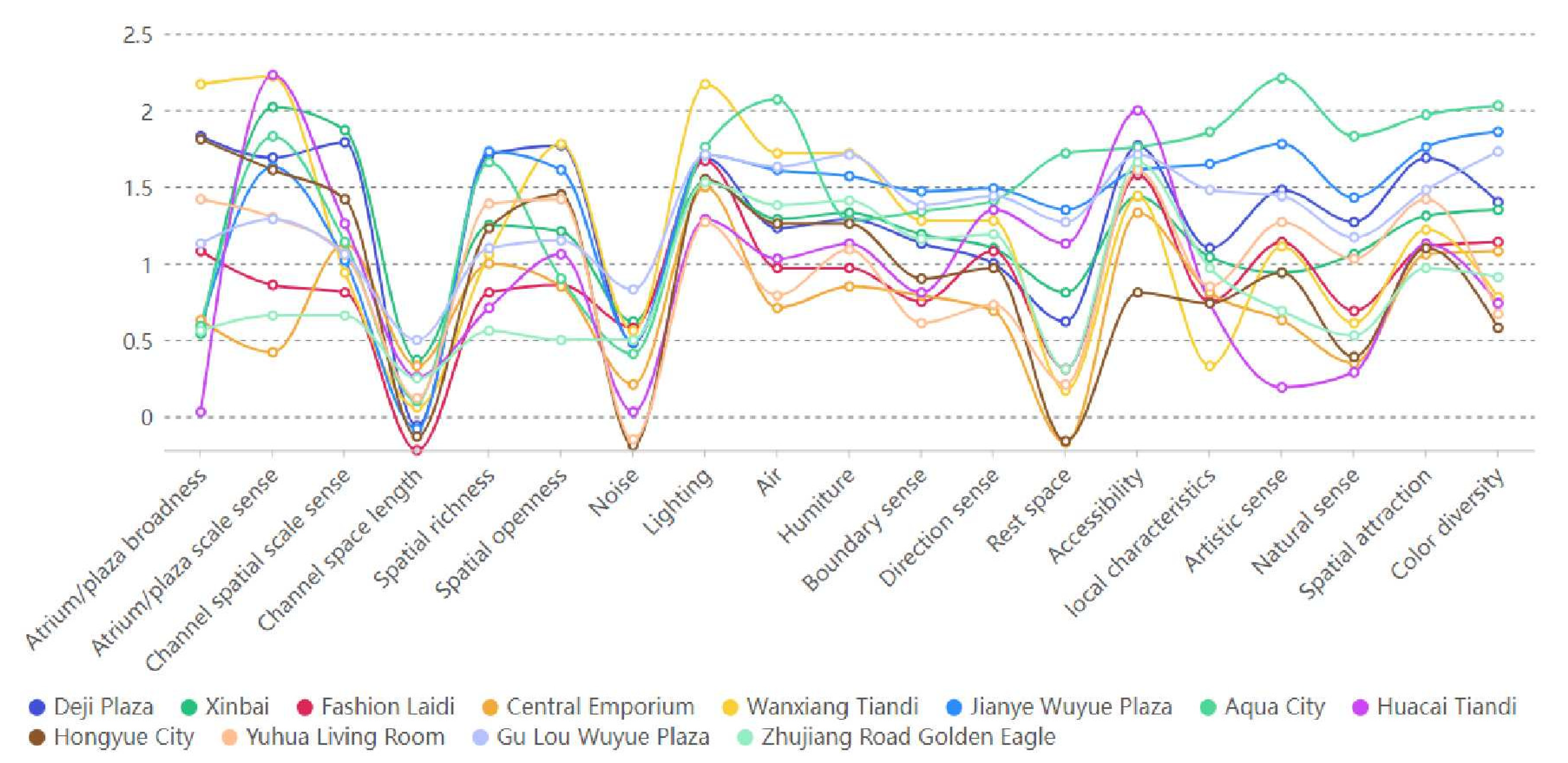

3.1. Individual Characteristics, Social Activity Levels, and SD Evaluation Levels

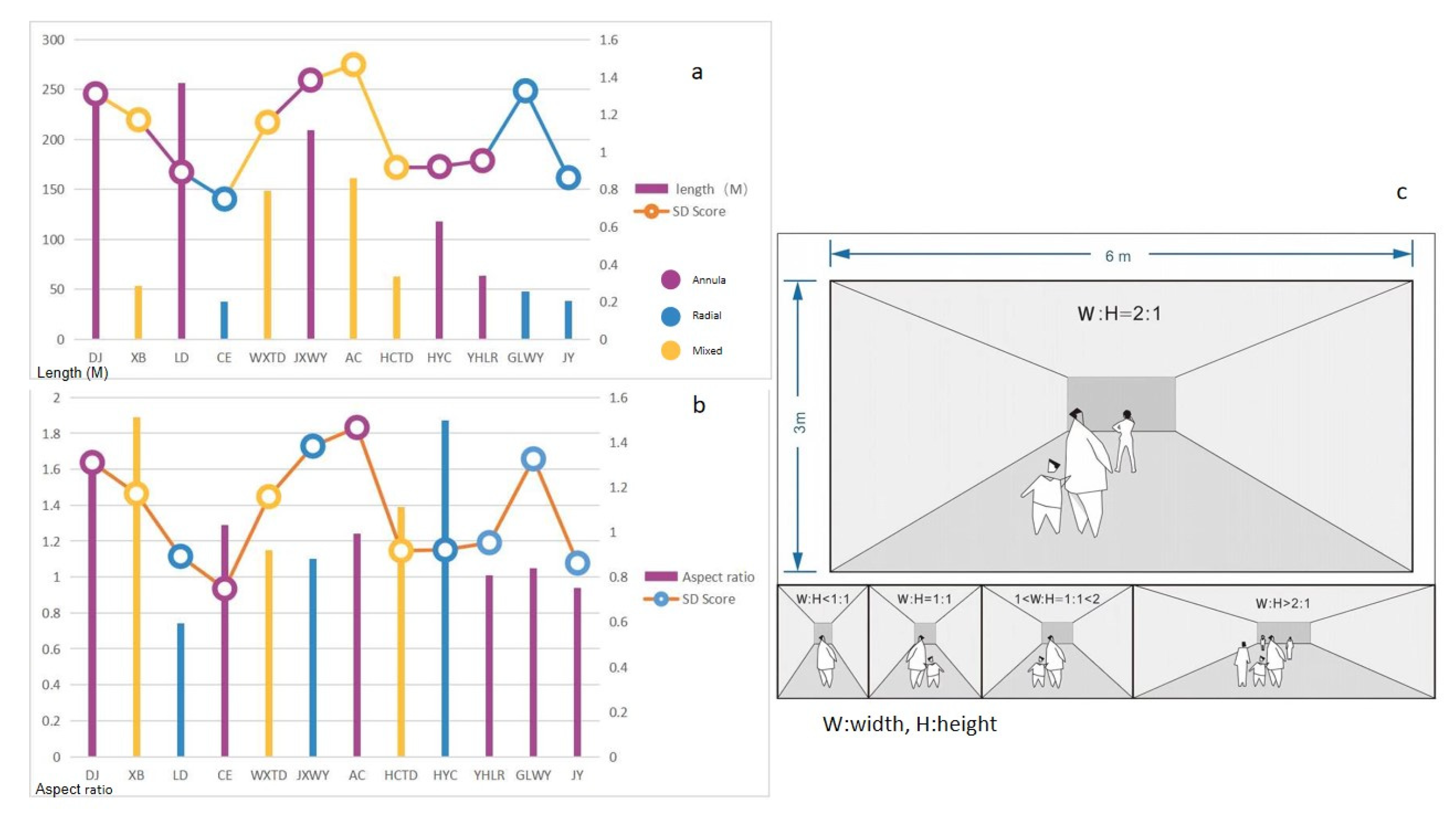

3.2. Architectural Spatial Characteristics

3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

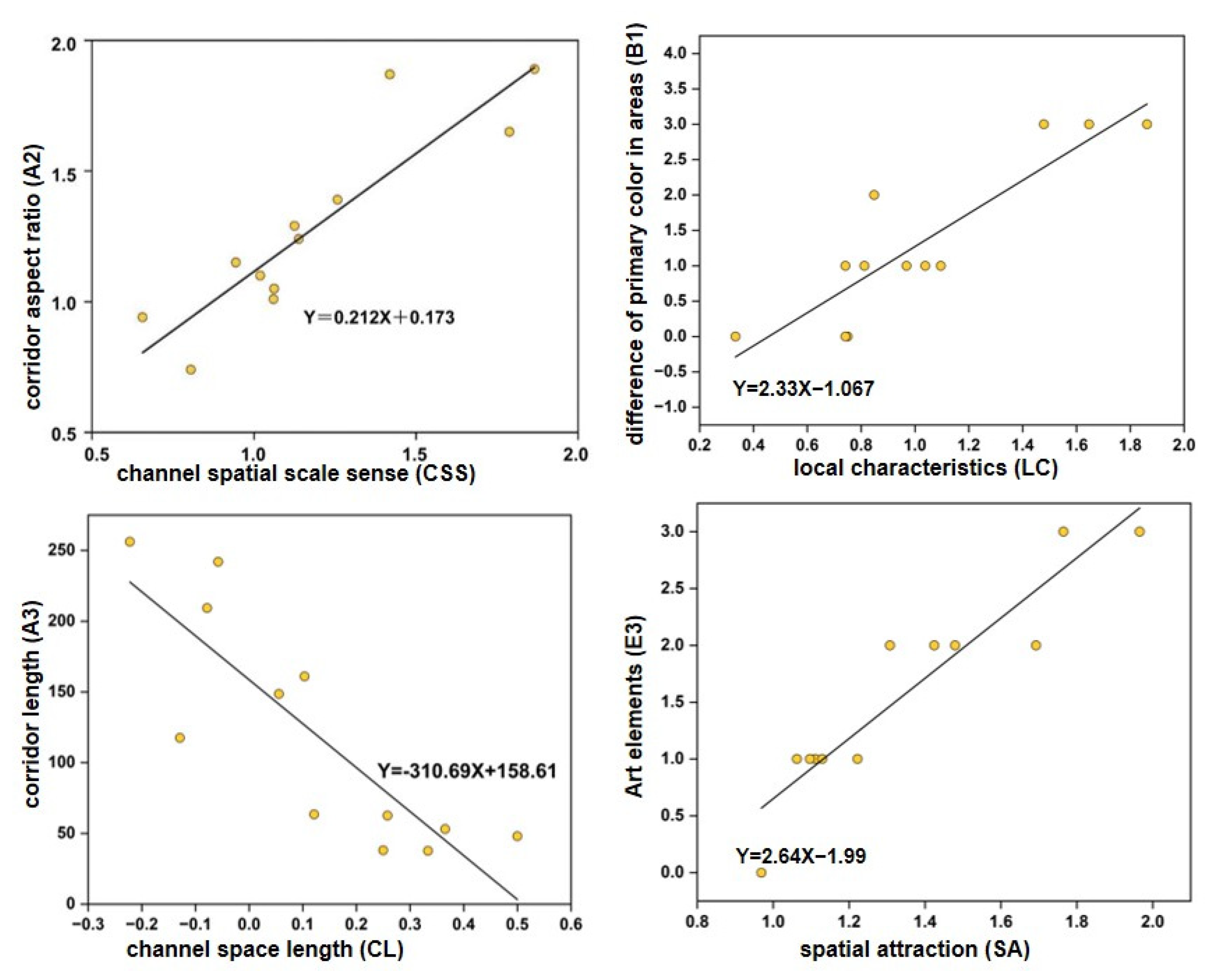

3.3.1. Correlation Between User Perceptions and Architectural Spatial Characteristics

3.3.2. Impact of Individual Characteristics and Social Activity Level on User Perceptions

3.3.3. Impact of Architectural Spatial Characteristics on User Perceptions

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual Characteristics and Social Activity Level Within USMs

4.2. Spatial Feature Elements of USM Image

4.3. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Users generally have a positive attitude toward the current underground environment. In the survey sample, the SD score of Aqua City was the highest at 1.47. There were notable differences in the subjective views of users on different attributes of the 12 USMs. USM shows the trends of humanization, human culture, and landscape in spatial characteristics. The spatial feature data for the USMs reflects the diversity of the samples. This preference aligns with sustainable urban development goals by promoting long-term user retention, which reduces the need for resource-intensive renovations due to low acceptance.

- (2)

- The comfort of USMs was largely determined by various architectural spatial characteristics and individual and social activity level characteristics. The subjective experiences of USM users were found to be predominantly shaped by seven spatial characteristics—corridor form, corridor length, color differentiation, number of internal functional spaces, entrance form, signage system, and natural elements. In USMs with high user satisfaction, the average annular corridor was 177.7 m long, whereas the average radial corridor was 44.6 m long. Experiences were further affected by five individual and social activity level characteristics—age, orientation method employed, choice of entrance, and the day and time of interview. These findings directly support energy conservation strategies.

- (3)

- The findings of this study support a stronger emphasis on human-centered design by suggesting improvements that (a) enhance the various connectivities of USMs; (b) refine the functional zoning and configuration according to diversified demand; (c) adopt a “fishbone” spatial layout with well-proportioned paths and clear nodes to relieve the discomfort caused by crowding in the dining area during peak hours; and (d) incorporate cultural and novel landmarks into USMs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hooimeijer, F.L.; Tummers, L.C. Integrating subsurface management into spatial planning in The Netherlands, Sweden and Flanders. Urban Des. Plan. 2017, 170, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D.V.L.; Makana, L.O.; Jefferson, I.; Rogers, C.D.F. Liveable cities and urban underground space. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, R.; Carmody, J. Underground Space Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Broere, W. Urban underground space: Solving the problems of today’s cities. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Leng, J.; Qi, D.; Kumar, P.; Chen, T. Sustainable underground spaces: Design, environmental control and energy conservation. Energy Build. 2022, 257, 111779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, S. The future of the underground space. Cities 1999, 16, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.Q.; Nelson, J.D. Underground transport: An overview. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 87, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Yu, M. Deep Shanghai project—A strategy of infrastructure integration for megacities. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 81, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, H. On utilization of underground space to protect historical relics model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2009, 24, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd Thomas, J.; Lee Okleshen Peters, C. The underground mall: An investigation of factors influencing gray market consumption. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Su, S.; Lu, W.; Yao, Y. Estimating spatiotemporal contacts between individuals in underground shopping streets based on multi-agent simulation. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 882904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I.; Gilboa, S.; Mitchell, V. Experiencing atmospherics: The moderating effect of mall experiences on the impact of individual store atmospherics on spending behavior and mall loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Lu, M.; Heo, M.Q.; Soh, C.K. Social aspects of working in underground spaces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Kwok, K.W.; Roberts, A.C.; Soh, C.K. A psychosocial approach to understanding underground spaces. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J.; Monnikhof, R.; Haasnoot, J.K.; Hoeven, F.v.d.; Horvat, E.; Krogt, R.v.d. Strategic study on the utilization of underground space in the Netherlands. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1998, 13, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hane, T.; Muro, K.; Sawada, H. Psychological factors involved in establishing comfortable underground environments. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Underground Space and Earth Sheltered Buildings: Urban Underground Utilization, Tokyo, Japan, 3 December 1991; pp. 480–492. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.Q.; Allan, A.; Lin, D. SWOT analysis and development strategies for underground pedestrian systems. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 87, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, K.; Kłosek-Kozłowska, D. Passengers’ experience in underground non-transfer metro stations: The impact of spatial characteristics. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 143, 105482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, S.; Sarıyıldız, S. A systematic quality assessment of underground spaces—Public transport stations. Cities 2001, 18, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamidurai, S. Evaluation of people’s willingness to use underground space using structural equation modeling—Case of Phoenix market city mall in Chennai city, India. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 91, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hoeven, F.; Juchnevic, K. The significance of the underground experience: Selection of reference design cases from the underground public transport stations and interchanges of the European Union. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Shi, S. Evaluation of underground space perception: A user-perspective investigation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shim, I.K.; Won, S.R.; Hwang, E.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, S.; Ryu, J.; Lee, J.C. Indoor air quality and its determinants in underground shopping malls in Korea. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, R.; Takizawa, A. Partitioning vertical evacuation areas in Umeda Underground Mall to minimize the evacuation completion time. Rev. Socionetwork Strateg. 2019, 13, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, H.; Li, F.; Xiao, Q. A study on the soundscape of underground commercial space in Lu’an City and Hefei City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nang, E.E.K.; Abuduxike, G.; Posadzki, P.P.; Divakar, U.; Visvalingam, N.; Nazeha, N.; Dunleavy, G.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Soh, C.K.; Jarbrink, K.; et al. Review of the potential health effects of light and environmental exposures in underground workplaces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Roberts, A.C.; Kwok, K.W.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Soh, C.K. Employee experiences in underground workplaces: A qualitative investigation. Ergonomics 2020, 63, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Cao, B.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.; Li, Z.; Long, Y.; Li, X. Effect of thermal, acoustic, and lighting environment in underground space on human comfort and work efficiency: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, R.; Bian, W. Research on environmental comfort and cognitive performance based on EEG+VR+LEC evaluation method in underground space. Build. Environ. 2021, 198, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-U.; Jang, J.-H.; Choi, Y. Analysis on the factors affecting the satisfaction of underground shopping centers: From the cases in Busan Metropolitan Region. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Q. A study and application of the degree of satisfaction with indoor environmental quality involving a building space factor. Build. Environ. 2018, 143, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Roberts, A.C.; Yap, H.S.; Car, J.; Kwok, K.W.; Soh, C.-K.; Christopoulos, G.I. White- and blue-collar workers’ responses towards underground workspaces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 105, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Kang, J.; Jin, H. Field study on the influence of spatial and environmental characteristics on the evaluation of subjective loudness and acoustic comfort in underground shopping streets. Appl. Acoust. 2013, 74, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeven, F.v.d.; Nes, A.v. Improving the design of urban underground space in metro stations using the space syntax methodology. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2014, 40, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Künzli, O. An introduction to connectivity concept and an example of physical connectivity evaluation for underground space. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasertsubpakij, D.; Nitivattananon, V. Evaluating accessibility to Bangkok Metro Systems using multi-dimensional criteria across user groups. IATSS Res. 2012, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylinen, J. Spatial planning in subsurface architecture. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1989, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, L.A.; Clavell, G.G. The TramArt experience: Domesticating graffiti in public transport. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2016, 9, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.S.; Lam, W.H.K. Levels of service for stairways in Hong Kong underground stations. J. Transp. Eng. 2003, 129, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, J.C.; Sterling, R.L. Design strategies to alleviate negative psychological and physiological effects in underground space. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1987, 2, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Shen, Z.; Luo, J. Post-occupancy evaluation of user satisfaction: Case studies of 10 urban underground complexes in China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 143, 10550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liao, J.; Guo, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K. Lighting environment analysis of Chengdu underground commercial spaces. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 741, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S. Spatial cognition and the processing of verticality in underground environments. In Proceedings of the Conference on Spatial Information Theory, Morro Bay, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.C.; Liang, S.; Chen, B.B.; Wu, C.L. Investigation on the impacts of natural lighting on occupants’ wayfinding behavior during emergency evacuation in underground space. Energy Build. 2022, 255, 111613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Park, S. Study of effective corridor design to improve wayfinding in underground malls. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 631531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, D.; Yang, H.; Liu, W.; He, G.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y.; Shen, S. Research on pathfinding cognition in complex underground public space utilizing eye movement and EEG synchronous detection. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 16, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategy Consulting Center of the Chinese Academy of Engineering; The Urban Sustainable Development Branch of the China Society of Resource Management and Environment. China’s Urban Underground Space Development Blue Book; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. Cognition and Environment: Coping in an Uncertain World; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C.E. The nature and measurement of meaning. Psychol. Bull. 1952, 49, 197–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, L. Research on the healing effect evaluation of campus small-scale courtyards based on the method of semantic differential and the perceived restorative scale. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.W.; Wong, H.M.; Mak, C.M. A systematic review of human perceptual dimensions of sound: Meta-analysis of semantic differential method applications to indoor and outdoor sounds. Build. Environ. 2018, 133, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organisations across nations. Aust. J. Manag. 2002, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, S. Perception Aspects in Underground Spaces Using Intelligent Knowledge Modeling. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- T/CSRME 012-2021; Standard for Quality Evaluation of Urban Underground Space. Chinese Society for Rock Mechanics and Engineering: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Kanire, G. Social Science Research Methodology: Concepts, Methods and Computer Applications; GRIN Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Uncovering the relationship among spatial vitality, perception, and environment of urban underground space in the metro zone. Undergr. Space 2023, 12, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrock, S.; Van Acker, M.; Admiraal, H.W. Design recommendations for sustainable urban underground spaces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 140, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.M.; Hölscher, C.; Büchner, S.; Konieczny, L. Gaze behaviour during space perception and spatial decision making. Psychol. Res. 2012, 76, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongbumru, T.; Dewancker, B. Post-occupancy evaluation of user satisfaction: A case study of “old” and “new” public housing schemes in Bangkok. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2016, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Roberts, A.C.; Lee, E.H.; Kwok, K.-W.; Car, J.; Soh, C.K.; Christopoulos, G. Transitional areas affect perception of workspaces and employee well-being: A study of underground and above-ground workspaces. Build. Environ. 2020, 179, 106840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machleit, K.A.; Kellaris, J.J.; Eroglu, S.A. Human versus spatial dimensions of crowding perceptions in retail environments: A note on their measurement and effect on shopper satisfaction. Mark. Lett. 1994, 5, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Astous, A. Irritating aspects of the shopping environment. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Chebat, J.C. The interaction of retail density and music tempo: Effects on shopper responses. Psychol. Mark. 2005, 22, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brengman, M.; Willems, K.; Joye, Y. The impact of in-store greenery on customers. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerrebroeck, H.; Brengman, M.; Willems, K. Escaping the crowd: An experimental study on the impact of a virtual reality experience in a shopping mall. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Zhang, S. A pilot study of circulation layout based on perceived retail crowding. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.H.; Hu, J.Y.; Zhang, S.S.; Huang, J.Y. Sense of security evaluation of underground streets in Japan from the pedestrians’ perspective: A case study of Nagoya. New Archit. 2021, 1, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ortegón-Cortázar, L.; Royo-Vela, M. Nature in malls: Effects of a natural environment on the cognitive image, emotional response, and behaviors of visitors. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.A.; Greene, T.C.; Fisher, G.D.; Baum, A. Environmental Psychology, 5th ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Classification | Attribute | Adjective Pair | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spatial form | Atrium/plaza broadness (APB) | Narrow/Wide |

| 2 | Atrium/plaza scale sense (APS) | Repressed/Wide-open | |

| 3 | Channel spatial scale sense (CSS) | Repressed/Wide-open | |

| 4 | Channel space length (CL) | Short/Long | |

| 5 | Spatial richness (SR) | Single/Rich | |

| 6 | Spatial openness (SO) | Closed/Open | |

| 7 | Physiological environment | Noise (N) | Noticeable/Slight |

| 8 | Lighting (L) | Insufficient/Plenty | |

| 9 | Air (A) | Poor/Clear | |

| 10 | Humiture (H) | Uncomfortable/Suitable | |

| 11 | Functional service | Boundary sense (BS) | Blurred/Clear |

| 12 | Direction sense (DS) | Confused/Clear | |

| 13 | Rest space (RS) | Insufficient/Sufficient | |

| 14 | Accessibility (Ac) Local characteristics Local characteristics | Inconvenient/Convenient | |

| 15 | Esthetic experience | Local characteristics (LC) | Indistinctive/Distinctive |

| 16 | Artistic sense (AS) | Unartistic/Artistic | |

| 17 | Natural sense (NS) | Unnatural/Natural | |

| 18 | Spatial attraction (SA) | Unattractive/Attractive | |

| 19 | Color diversity (CD) | Single/Various |

| Element | Survey Content | References |

|---|---|---|

| Paths | A1. Corridor form; A2. Corridor aspect ratio (W:H); A3. Corridor length (m). | [18,22,41,58,59] |

| Edges | B1. Difference in primary color in areas; B2. Difference in primary lighting in areas; B3. Proportion of daylight brought from glass ceilings in the area of the total area (%). | |

| Districts | C1. Number of internal space functions (kinds). | |

| Nodes | D1. Entrance form; D2. Atrium plan form; D3. Atrium area (m2); D4. Square area (m2); D5. Square aspect ratio (W:H); D6. Sunken square area (m2). | |

| Landmarks | E1. Natural elements; E2. Number of resting seats (places); E3. Art elements; E4. Signage systems. |

| Attribute | Category | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0—Annular type 1—Radial type 2—Mixed type | 41.7% 25% 33.3% | ||||||

| B1 | 0—None 1—One difference 2—Two differences 3—Three differences | 25% 41.7% 8.3% 25% | B2 | 0—None 1—One difference 2—Two differences 3—Three differences | 16.7% 41.7% 8.3% 33.3% | |||

| D1 | 0—Basic layout (UP + GF) 1—Complex layout (UP + GF + Sur) 2—Complex layout (UP + GF + Sub) 3—Network layout (UP + GF + Sub + Sur) | 8.3% 33.3% 41.7% 16.7% | D2 | 0—Regular type 1—Curved type 2—Free fold type | 16.7% 33.3% 8.3% | |||

| E1 | 0—None 1—One kind 2—Two kinds | 33.3% 50% 16.7% | E3 | 0—None 1—One–two kinds 2—>Two kinds | 8.3% 75% 16.7% | E4 | 0—Two kinds 1—Three–four kinds 2—>Four kinds | 16.7% 58.3% 25% |

| Individual Characteristic | B | Std. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female | −0.34 −0.68 | 0.16 * 0.12 *** |

| Age (years) | <18 18–25 25–36 36–45 46–55 >55 | −0.51 −0.53 −0.69 −1.02 1.38 −0.47 | 0.32 0.14 *** 0.17 *** 0.27 *** 0.18 *** 0.86 |

| Frequency of visits | Occasionally Often, but not every day Almost every day | −0.52 −0.65 −0.45 | 0.12 *** 0.16 *** 0.14 *** |

| Method of orientation | Sense of orientation Visual information signs Both | −0.44 −1.01 −0.39 | 0.21 * 0.20 *** 0.13 ** |

| Entrance | Souterrain Subway Ground Underground parking | −0.76 −0.61 −0.54 −0.30 | 0.23 ** 0.17 *** 0.16 *** 0.23 |

| Time of interview | 09:00–11:00 11:00–14:00 14:00–19:00 19:00–22:00 | −0.52 −0.55 −0.85 0.14 | 0.21 * 0.16 *** 0.18 *** 0.24 |

| Day of week of interview | Working day Weekend | −0.14 −0.72 | 0.18 0.11 *** |

| Element | Characteristic | B | Std. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | A1. Corridor form A2. Corridor aspect ratio A3. Corridor length | −1.38 −0.36 −0.91 | 0.12 *** 0.17 0.22 * |

| Edges | B1. Difference in primary color in areas B2. Difference in primary lighting in areas B3. Daylight proportion | 0.99 0.44 0.28 | 0.14 ** 0.16 ** 0.76 |

| Districts | C1. Number of internal space functions | −1.38 | 0.11 *** |

| Nodes | D1. Entrance form D2. Atrium plan form D3. Atrium area D4. Square area D5. Square aspect ratio D6. Sunken square area | −0.98 0.17 0.40 −0.40 −0.40 −0.28 | 0.18 ** 0.25 0.21 * 0.21 * 0.21 * 0.76 |

| Landmarks | E1. Natural elements E2. Number of resting seats E3. Art elements E4. Signage systems | 0.97 −0.40 −0.33 0.99 | 0.14 ** 0.64 0.71 0.23 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Guo, D.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Du, C.; Chen, Z. Sustainable Comfort Design in Underground Shopping Malls: A User-Centric Analysis of Spatial Features. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062717

Zhao X, Guo D, Chen Y, Wu Y, Zhu X, Du C, Chen Z. Sustainable Comfort Design in Underground Shopping Malls: A User-Centric Analysis of Spatial Features. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062717

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xingxing, Dongjun Guo, Yulu Chen, Yanhua Wu, Xingping Zhu, Chunhui Du, and Zhilong Chen. 2025. "Sustainable Comfort Design in Underground Shopping Malls: A User-Centric Analysis of Spatial Features" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062717

APA StyleZhao, X., Guo, D., Chen, Y., Wu, Y., Zhu, X., Du, C., & Chen, Z. (2025). Sustainable Comfort Design in Underground Shopping Malls: A User-Centric Analysis of Spatial Features. Sustainability, 17(6), 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062717