Enhancing Student Behavior with the Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Hospitality Education: Integrating Sustainability Learning

2.2. Fostering a Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Rationale for Using the Case Study Methodology

3.2. Data Collection for Sustainability Learning

3.3. Data Analysis: Reliability, Validity, and Research Ethics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Enhancing Responsible Behavior Through Food and Agriculture Education

I do not feel like I work hard, because this course is interesting, and we know how to coordinate when the teacher has assignments. We have 10 plots that must be farmed, which we counted as 1–1 to 1–10. The plots were sown at the same time, because different seeds needed different growing times, and some seeds grow fast such as water spinach. Although we work in the hot weather, my classmates and I do not mind, and it feels different from classroom because we have never had an experience like this. The course is giving us a deep understanding of why my mother always said “please eat food cleanly, do not waste food and let the farmer cry”.

We felt so amazed when the teacher set up an insect trap to catch Spodoptera litura, which is a kind of pest. The teacher asked us to use an empty PET bottle to make an insect sex pheromone trap. Sex pheromones of a female worm were kept in the bottle, and after several days, male pests came and then died in the bottle. When we counted the corpses of the pests, we felt amazing that we had killed pests without using chemical pesticides.

4.2. The Green Restaurant: Responsible Consumption in Entrepreneurship Simulation

I am so happy and honored to be invited to this welcome banquet after my speech—The Sustainable Development of Seafood Restaurants in Singapore. I am surprised at how the students can cook Singaporean food. Because Hainan Chicken Rice tasted so wonderful when I ate it in Singapore. But students can make it with local food materials. Those are wonderful cooking skills. If your students want internships in Singapore, I am willing to offer several positions in Marina Bay Sands, where our branch must provide high-level experience. Of course, a higher price is necessary to show a precious meal. Our team endeavors to use sustainable development in human resource management, and we also have different training courses for seafood cooking and purchasing, especially chili crab and fresh fish. We use local food materials which can assure the quality.

We highlighted that our reservations (lunch, dinner, and afternoon tea) were focused on the Singaporean food style, but all the meals were purchased from local agriculture. We worked as a team, from menu design to each delicious food’s production and service. Food materials were purchased at a volume suitable to the orders, which ensured that no food from small farmers was wasted. We reused onionskin as detergent, chicken bones to make pottage, and oranges decorated the meals and beverages at the same time. Table setting did not use disposable tableware, and instead used cloth napkins. The real plants and posters promoted the environmentally friendly concept. A QR code was used to understand customer satisfaction and whether the customers knew they were eating local food in a Singaporean style in a green restaurant. I knew at least 90% of the customers, and they were impressed that we are making green foods and beverages in school.

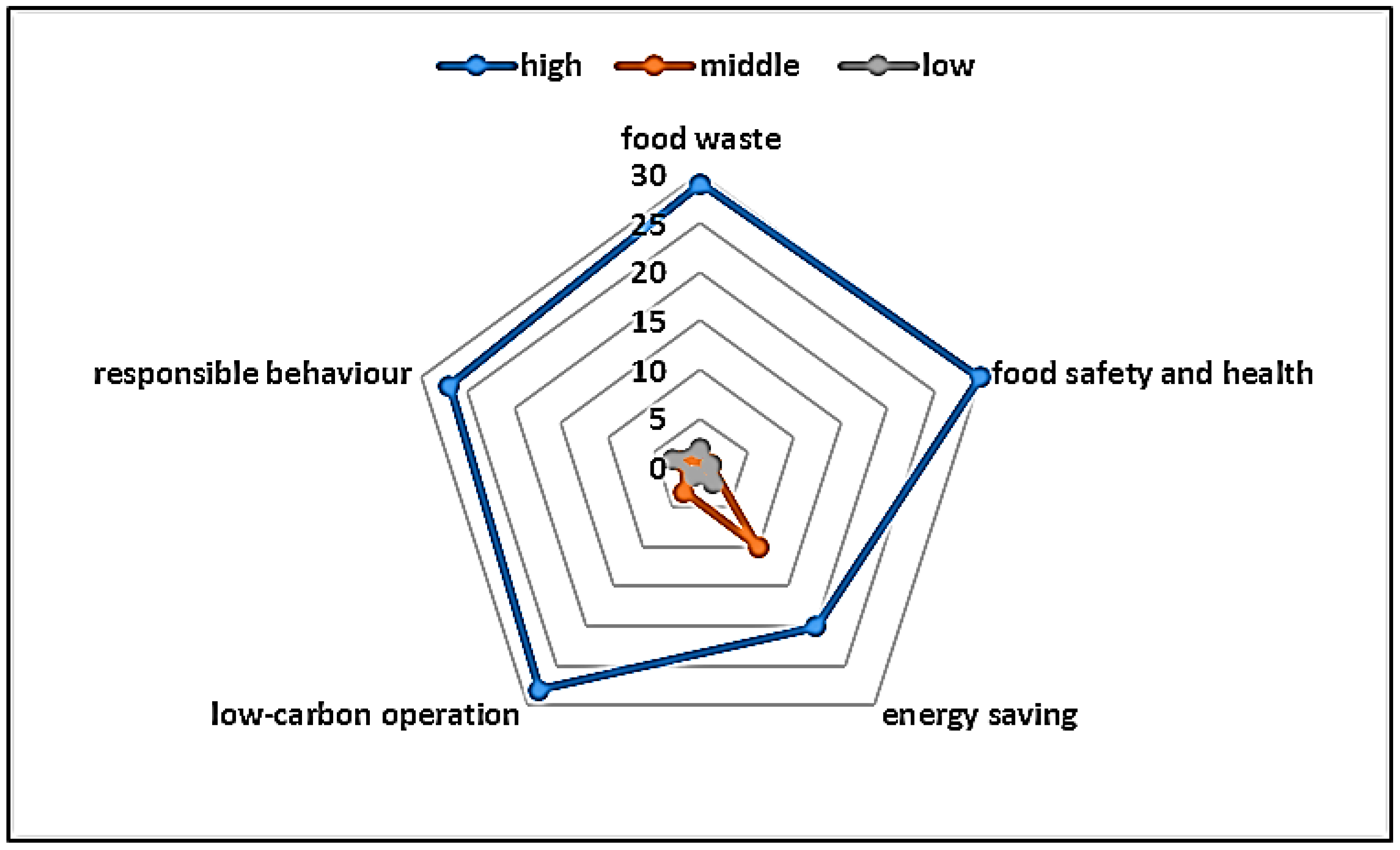

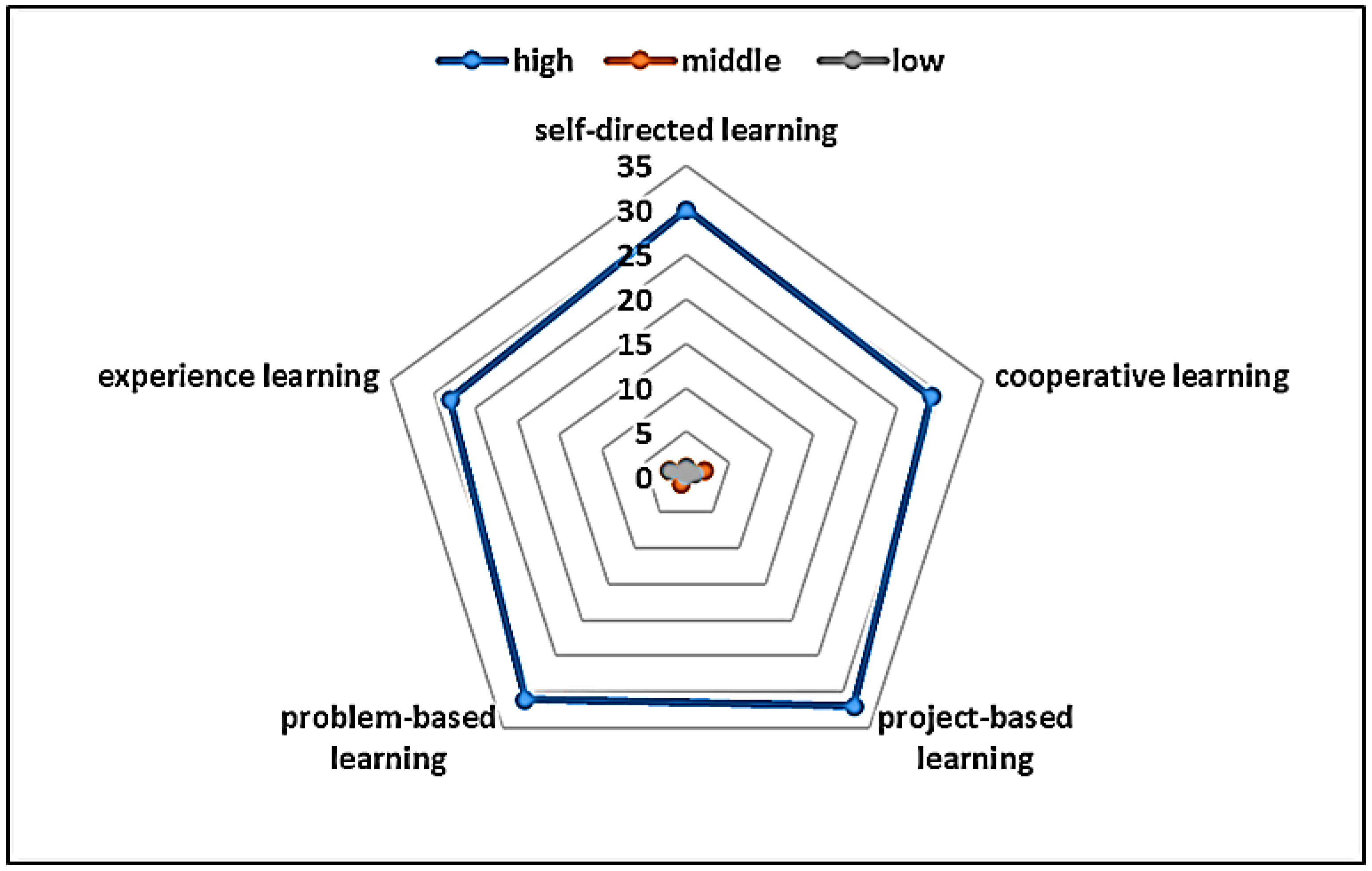

4.3. Evaluation of Sustainable Hospitality Education

4.4. Constructing the Conceptual Framework for Integrating ESD for 2030 into Hospitality Education

- In the B2B hospitality–health supply chain for responsible consumption

- In B2C hospitality-health supply chain for responsible production

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huber, M.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Średnicka, D.; Bügel, S.; Van De Vijver, L.P.L. Organic food and impact on human health: Assessing the status quo and prospects of research. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Abd Elmoneim, O.E.; Khan, M.I.; Patel, M.; Alreshidi, M.; Adnan, M. Innovations in nanoscience for the sustainable development of food and agriculture with implications on health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition. 10 July 2023. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023 (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Barrett, C.B. Measuring food insecurity. Science 2010, 327, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girotto, F.; Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Food waste generation and industrial uses: A review. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; Falegnami, A.; Meleo, L.; Romano, E. The Green SCENT Competence Frameworks. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, G.; Ganguli, M.; Chandra, V.; Sharma, S.; Belle, S.; Seaberg, E.; Pandav, R. Effects of literacy and education on measures of word fluency. Brain Lang. 1998, 61, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Gregory, P.J. Soil, food security and human health: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 66, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulla, K.; Leal Filho, W.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Burgomaster, C. Sustainable development education in the context of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap (ESD for 2030). 2022. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=en (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Cornia, G.A. Farm size, land yields and the agricultural production function: An analysis for fifteen developing countries. World Dev. 1985, 13, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Lopez, C.; Zubairu, N.; Chen, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Modelling enablers for building agri-food supply chain resilience: Insights from a comparative analysis of Argentina and France. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 35, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, O.; Villalobos, J.R. Application of planning models in the agri-food supply chain: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, M.L. Regional food culture and development. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á.; Sáez-Martínez, F.J. Eco-innovation: Insights from a literature review. Innovation 2015, 17, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjozkina, G.; Melanthiou, Y. Is tourism and hospitality education supporting sustainability? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P.; Jameson, S. Challenges in hospitality management education: Perspectives from the United Kingdom. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degieter, M.; Gellynck, X.; Goyal, S.; Ott, D.; De Steur, H. Life cycle cost analysis of agri-food products: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 158012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felce, D.; Perry, J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Res. Dev. Disabil. 1995, 16, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gallear, D.; Rudd, J.; Foroudi, P. The impact of brand value on brand competitiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haston, W. Teacher modeling as an effective teaching strategy. Music Educ. J. 2007, 93, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Wu, S.T. A case study of sustainable hospitality education relating to food waste from the perspective of transformative learning theory. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. A conceptual framework of sustainable hospitality supply chain management. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L. Transport and climate change: A review. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, R.; Chang, D.; Sarwar, S.; Chen, W. Forest, agriculture, renewable energy, and CO2 emission. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4231–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K.; Jiborn, M.; Wood, R.; Többen, J.; Seto, K.C. Carbon footprints of 13,000 cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 064041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer-Remmers, A.; Ivanova, V.; Brandsma-Dieters, A. To act or not to act: Cultural hesitation in the multicultural hospitality workplace. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 11, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Clark, W.C.; Corell, R.; Hall, J.M.; Jaeger, C.C.; Lowe, I.; McCarthy, J.J.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Bolin, B.; Dickson, N.M.; et al. Sustainability science. Science 2001, 292, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T.; Burwell, D. Issues in sustainable transportation. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2006, 6, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.O.; Caamal-Olvera, C.G.; Luna, E.M. Mobility and sustainable transportation in higher education: Evidence from Monterrey Metropolitan Area in Mexico. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Farmer, G. Reinterpreting sustainable architecture: The place of technology. J. Archit. Educ. 2001, 54, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisbeck, P. Green architecture and the good anthropocene. In Architects, Sustainability and the Climate Emergency; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, C.; Fechner, D.; Dolnicar, S. Progress in field experimentation for environmentally sustainable tourism—A knowledge map and research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Kilic, H.; Akhshik, A. Education for sustainable tourism development: An exploratory study of key learning factors. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Krogh, G.; Geilinger, N. Knowledge creation in the eco-system: Research imperatives. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajk, T.; Van Isacker, K.; Aberšek, B.; Flogie, A. STEM Education in Eco-Farming Supported by ICT and Mobile Applications. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TM, A.; Kaur, P.; Ferraris, A.; Dhir, A. What motivates the adoption of green restaurant products and services? A systematic review and future research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2224–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.J.; Pan, S.Y.; Lee, I.; Kim, H.; You, Z.; Zheng, J.M.; Chiang, P.C. Green transportation for sustainability: Review of current barriers, strategies, and innovative technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, H.; Goncharenko, R.; Theunisz, C.; Vadasz, T. When green meets green. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 78, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Santos, G.; Pagano, A.; Murmura, F. Environmental management system according to ISO 14001: 2015 as a driver to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2599–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olt, J.; Maksarov, V.V.; Soots, K.; Leemet, T. Technology for the production of environment friendly tableware. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2020, 24, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.J.; Mohammed, M.K. Fabrication of efficient triple-cation perovskite solar cells employing ethyl acetate as an environmental-friendly solvent additive. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 158, 112047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, L.; Gossiaux, P.B.; Rauch, C.P.; Tabiou, S. ‘Learning by doing’: A teaching method for active learning in scientific graduate education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 30, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; Spohrer, J.C. Learner-centered education. Commun. ACM 1996, 39, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.; Crooks, D.; Lunyk-Child, O. A new perspective on competencies for self-directed learning. J. Nurs. Educ. 2002, 41, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremner, N.; Sakata, N.; Cameron, L. The outcomes of learner-centred pedagogy: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 94, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, I. Teacher roles in the learner-centred classroom. ELT J. 1993, 47, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranen, J.; Vesterinen, V.M.; Aksela, M. From learner-centered to learner-driven sustainability education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E.; Parr, D.; Van Soelen Kim, J.; Beckett, J.; Lickter, M.; Ballard, H. Transformative food systems education in a land-grant college of agriculture: The importance of learner-centered inquiries. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, L.H.; Chen, C.L. Collaborative learning by teaching: A pedagogy between learner-centered and learner-driven. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The case study method in social inquiry. Educ. Res. 1978, 7, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudzina, M.R. Case study as a constructivist pedagogy for teaching educational psychology. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1997, 9, 199–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. Reflection and teacher education: A case study and theoretical analysis. Interchange 1984, 15, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, K.; Kopciwicz, L.; Dahlgren, L.O. Learning for an unknown context: A comparative case study on some Swedish and Polish Political Science students’ experiences of the transition from university to working life. Compare 2008, 38, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, H.G.; Gallimore, R.; Weisner, T.S.; Turner, J.L. Teaching participant-observation research methods: A skills-building approach. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1980, 11, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, D.A.; Martinez-Levasseur, L.M.; Provencher, J.F.; Debets, C.D.; Appaqaq, M.; Houde, M. Engaging Inuit youth in: Braiding Western science and through school workshops. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 53, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Do, M.H. Review of empirical research on university social responsibility. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2021, 35, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture Bureau of Kaohsiung City Government. Green Friendly Restaurant. 14 November 2022. Available online: https://agri-en.kcg.gov.tw (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Kaczynski, D.; Wood, L.; Harding, A. Using radar charts with qualitative evaluation: Techniques to assess change in blended learning. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Climate Change Conference. COP 28 (Conference of the Parties 2023). Available online: https://unfccc.int/cop28 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Hill, H. NCAT Research Specialist. 2008. Available online: https://attra.ncat.org/publication/food-miles-background-and-marketing (accessed on 2 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.-Y.; Hung, C.-L.; Yen, C.-Y.; Su, Y.; Lo, W.-S. Enhancing Student Behavior with the Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093821

Liu S-Y, Hung C-L, Yen C-Y, Su Y, Lo W-S. Enhancing Student Behavior with the Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093821

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shang-Yu, Chin-Lien Hung, Chen-Ying Yen, Yen Su, and Wei-Shuo Lo. 2025. "Enhancing Student Behavior with the Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093821

APA StyleLiu, S.-Y., Hung, C.-L., Yen, C.-Y., Su, Y., & Lo, W.-S. (2025). Enhancing Student Behavior with the Learner-Centered Approach in Sustainable Hospitality Education. Sustainability, 17(9), 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093821