Abstract

Children are an important stakeholder group for sustainable development, as they represent the interface between current and future generations. A comprehensive assessment of child development (CD) in the context of sustainable development is still missing. In this paper, as a first step, a literature review is conducted to identify relevant aspects and gaps related to the assessment of CD. The main issues of CD are categorized into seven themes: health, education, safety, economic status, relationships, participation, and newly proposed environmental aspects. The corresponding subthemes and criteria are classified accordingly (e.g., nutrition, child mortality, immunization, etc., are assigned to the theme health). However, gaps in current studies, such as the heterogeneous classification of relevant aspects, regional and societal bias in addressing certain aspects, the limited number of subthemes, and criteria and the missing inclusion of environmental aspects impede the assessment of sustainable child development. To address the existing gaps, a comprehensive framework, the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI), is proposed. The SCDI is based on sustainable development as the core value, considers relevant aspects of CD with regard to newly-proposed environmental aspects and includes 26 aspects on an outcome and 37 indicators on a context level to tackle the heterogeneous classifications and interdependencies of relevant aspects. The proposed index intends to strengthen the stakeholder perspective of children in sustainability assessment.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development (SD) has become an ultimate goal for societies globally. SD was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” by the Brundtland Commission [1]. This definition not only refers to intra- and inter-generational equity, but also to the right for every human being, whether adult or child, to be granted the opportunity to develop in freedom and in a well-balanced society by satisfying basic needs and protecting the environment [2,3,4]. Correspondingly, based on the definition stated by the United Nations, sustainability refers to use of the biosphere by present generations while maintaining its potential yield for future generations and/or non-declining trends of economic growth and development that might be impaired by natural resource depletion and environmental degradation [5]. In this context, the term environment refers to “the totality of all the external conditions affecting the life, development and survival of an organism [6]”. With regard to SD and sustainability, the definition of environment is specified, considering its carrying capacity [7,8]: “the use of renewable resources should not exceed regeneration rates and the rate of non-renewable resource use should not exceed the development of renewable substitutes…[7,8]”. The International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource et al. [9] stated that “we have not inherited the Earth from our parents, we have borrowed it from our children”. This statement highlights the significant relationship between inter-generational equity, children and SD.

Children (here defined as aged under 18 [10,11]) are the stakeholders inheriting and shaping the society. Child development (CD) is affected by external circumstances, and children are more vulnerable than adults [12]. For example, children are more susceptible to diseases, environmental pollution, violence and abuse. Furthermore, children’s basic rights to express opinions and to have access to education can be deprived by adults [12,13]. Disregard and violation of these basic rights and the principles of well-being can lead to irreversible and severe impacts on child development and, consequently, future societies.

There are several approaches for the assessment of sustainability. Recently, the life cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) method has received increasing attention. LCSA combines life cycle assessment (LCA), social LCA (SLCA) and life cycle costing (LCC) to comprehensively cover environmental, social and economic aspects [14,15]. To investigate social issues from a whole-population perspective, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) [16] proposes five stakeholder groups for SLCA: workers, consumers, local communities, value chain actors and societies. Despite the fact that children form future societies and their relevance in the context of SD, children are neglected as a relevant stakeholder group. However, any sustainability assessment method neglecting children’s interests and their influence on SD is insufficient. Consequently, the stakeholder group children should be added to LCSA or, for a simplified assessment, even replaces the current five stakeholder groups, acknowledging children’s relevance for the achievement of inter-generational equity.

As the needs of children and their susceptibility to external factors are different from those of adults, schemes and indexes for evaluating SD from a child perspective, that is sustainable child development (SCD), need to be developed independent of whole-population-oriented assessments, such as the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was introduced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in the 1990s to measure the state of a country to enable people to have long, healthy, and creative lives by combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income into a composite index based on national average data of the whole population [17]. Although HDI has been widely adopted to measure the degree of development of a country, relevant drawbacks remain. For example, environmental and resource consumption aspects are neglected, criteria related to income and gender equity are missing and impacts on future generations are ignored [18,19,20]. The NGO, Save the Children, proposed a Child Development Index (CDI) in 2008 [21,22] by applying an integrated index to evaluate the development of children with regard to health, education and basic needs. The CDI was designed as a mirror of the HDI, and both indexes address health and education themes. However, an indicator related to nutrition was taken up in the CDI to describe the basic need of children instead of using the indicator ‘income’ as proposed by in the HDI (the indicators are shown in Table 1). Similar to the HDI, the CDI still has several drawbacks and does not allow a comprehensive assessment of environmental and resource-consumption aspects in the context of SD.

Table 1.

The themes and indicators of HDI and CDI, adopted from the save the children Fund [21].

| Theme | Human Development Index (HDI) | Children Development Index (CDI) |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Life expectancy at birth | Under five mortality rate |

| Education | Mean years of schooling for adults aged 25 years; expected years of schooling for children of school entering age | Percentage of primary age children not in school |

| Basic needs | Gross national income per capita | Under-weight prevalence among children under five |

A comprehensive assessment of issues that affect the well-being of children is needed to acknowledge and give consideration to children’s vulnerability and the strong connection of CD and SD [13]. In recent years, according to the Handbook of Child Well-Being [23], studies related to CD and well-being have undergone five relevant movements: shifting from assessing single aspects, like health, to including multi-dimensional topics, such as child rights and well-being, including positive aspects instead of only negative ones, considering new themes (e.g., participation), reflecting what a child feels and needs from a child’s perspective and developing a composite index [24,25]. Several NGOs proposed child well-being indexes to include additional aspects, such as relationships with family, schooling and community, emotional well-being, safety, or social engagement [26,27,28]. These themes and associated subthemes can broaden and improve the CDI. However, other relevant themes (e.g., environmental aspects, such as resource vulnerability) are not yet considered in the Handbook of Child Well-Being and other current studies [23]. There is still no widely-accepted, clearly-stated and comprehensive index system to evaluate CD in the context of SD.

The objective of this study is to review literature related to the assessment of CD and to systematically identify the different aspects addressed in existing studies, including their frequency of being mentioned. Based on these results, existing gaps are identified from a top-down SD perspective.

On this basis, the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI) is proposed as a holistic concept covering existing priority areas of CD and addressing existing gaps by considering regional conditions and including environmental aspects. The SCDI intends to take a SD perspective in defining relevant themes, subthemes and criteria that affect CD. The SCDI framework will provide an innovative perspective to evaluate SD and highlights the fact that children and SD are mutually supporting [12]. In the following sections, current themes, subthemes and criteria related to CD, as well as existing gaps are identified and classified as a basis for the development of the SCDI.

2. Review of Themes Related to Sustainable Development of Children

In this section, a literature review related to child rights, CD and child well-being is presented as a basis for identifying relevant themes, subthemes, criteria and existing gaps. The evaluation is used as a basis to propose the structure of the SCDI. The themes, subthemes and criteria used in the SCDI need to have a clear link to the principles of CD and address relevant aspects of SD.

The rights of children have to be considered, since every child needs to be protected to live with their basic rights. Relevant principles related to CD need to be identified and considered for SD. Thus, as a first step, the basic rights of children and underlying themes regarding SD are identified and combined as a foundation for SCD. The right to survival, to development, to protection, and to participation are identified as the four basic child rights [10,11,29,30]. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [31] serve as a reference for ensuring that the rights and themes comply with SD goals. As a next step, after defining the frame for SCD, relevant themes, subthemes and criteria are identified based on existing studies of CD and child well-being. The results represent current best practice regarding the assessment of SCD. In the following, the rights of children, the MDGs and the relevant themes, subthemes and criteria are analyzed and classified to provide a systematic overview of SCD.

2.1. Basic Rights of Children and Millennium Development Goals

Children are born with basic rights [29] (see the previous section). The protection of these basic rights needs to be considered as the core principles of SCD.

In 1989, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) of the United Nations defined basic rights of children, including the best interests of children, non-discrimination, participation, survival and development [10,11]. The CRC assigns children a relevant role in SD and provides a normative concept for understanding child well-being and CD [25,32,33]. Due to the broad spectrum of aspects covered, the rights defined by the CRC are often used as fundamental principles for the assessment of CD and well-being [25]. The NGO Child Right and You [29] further defined these rights by pointing out relevant themes: the right to survival (to life, health, nutrition, name and nationality), the right to development (to education, care, leisure and recreation), the right to protection (from exploitation, abuse and neglect), and the right to participation (to expression, information, thought and religion). In Table 2, a comprehensive overview of identified rights and corresponding themes is presented, based on data published by different NGO reports [10,11,29,30].

Table 2.

The basic rights of children and corresponding themes.

| Right | Theme |

|---|---|

| Right to survival | Physical and mental health |

| Nutrition | |

| Clean drinking water and sanitation | |

| Unpolluted environment | |

| Right to development | Education |

| Leisure | |

| Family relations | |

| Eliminate child labor | |

| Alternative care | |

| Free to choose religion | |

| Right to protection | Free from violence and crime |

| Free from exploitation | |

| Free from abuse | |

| Free from armed conflict | |

| Registration with nationality | |

| Right to participation | Express concern |

| Active participation in media |

Four basic rights are identified based on the literature review. Children should have these four rights no matter their gender, race, wealth and health conditions [11,33]. The right to survival for children includes four themes: health, enough food with sufficient nutrition, access to clean drinking water and sanitation and living in an unpolluted environment. The right to development refers to basic elements of child care and the children’s capability for working and exploring their daily life. The associated themes focus on parental and alternative care, education, leisure and religion. Next, protection and safe living conditions form another basic right. Children are very vulnerable, and negative external conditions can threaten their safety. In this regard, relevant themes to be considered encompass birth registration with nationality, violence and crime, exploitation, abuse and armed conflict. Finally, the right to participation refers to the right of children to be heard, to express their concerns on child-related issues and to have access to media [10,11,29,30]. All of these rights need to be considered as the foundation of SCD.

As a next step, the MDGs are analyzed, to check if the identified rights and themes reflect general SD goals. The MDGs are the most broadly supported development goals the world has ever agreed upon. The MDGs aim at holistically addressing development needs, globally and locally, to eliminate poverty towards SD. The UNDP stated eight MDGs [34] based on the United Nations Millennium Declaration in 2000 [31]:

- -

- Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger;

- -

- Achieving universal primary education;

- -

- Promoting gender equality and empowering women;

- -

- Reducing child mortality;

- -

- Improving maternal health;

- -

- Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases;

- -

- Ensuring environmental sustainability;

- -

- Developing a global partnership for development.

Verifying that the rights and themes identified earlier are compliant with the MDGs strengthens the fundamental structure of the assessment of CD and ensures the compliance of SCD with basic sustainable development goals. There are direct links between MDGs and the identified rights. For example, eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, reducing child mortality and combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases can directly link to the physical and mental health of the rights to survival. Besides, improving maternal health can also influence children’s health, since maternal conditions can affect the mortality rate of newborn babies and the health situation of children in early years. Furthermore, ensuring environmental sustainability means that children could live without the danger of environmental degradation, and the unpolluted environment is identified as a relevant theme for securing the rights to survival. Achieving universal primary education connects to the rights to children’s development in education. Through basic education, children can gain their capability for further development as human capital in society. Promoting gender equality and empowering women are relevant for decreasing gender discrimination, which link to the fundamental background in CRCs. Only one goal, developing a global partnership for development, is not pointed out in CRCs. However, the MDGs only represent selected urgent aspects for persuading countries to take actions towards SD, and the goals are limited to survival, education and discrimination issues. To make SCDI more comprehensive, additional aspects that may influence children’s well-being and development have to be considered.

Furthermore, in 2013, a publication of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) highlighted the importance to invest in the development and well-being of children as an integral instrument for achieving SD and reconfirms the rights and themes with basic sustainable development goals [12]:

- -

- SD starts with safe, healthy and well-educated children;

- -

- Safe and sustainable societies are, in turn, essential for children; and

- -

- Children’s voice, choice and participation are critical for the future that we want them to have.

Those aspects highlight that children are the foundation of SD and strongly support the rights and principles claimed in CRC and MDGs: health, safety, education and participation. Based on the rights and principles, the themes, subthemes and criteria related to SCD are identified and classified correspondingly through a literature review in the following section.

2.2. Identification of Themes, Subthemes and Criteria Relevant for Child Well-Being and Development

The basic question followed up in this section is: Which aspects of SD are of special relevance for children? This question needs to be answered by identifying relevant themes, subthemes and criteria based on a review of existing literature concerned with CD and well-being under consideration of the principles defined by the CRC and MDGs. Additional aspects relevant to SCD, which have not been covered in CRC or MDGs yet, are also identified.

To comprehensively address aspects related to CD and well-being, this article focuses on studies that refer to overall aspects of child development and well-being rather than ones with only specific emphasis on single areas, like physical health or education. The literature review includes ten academic publications [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], eight works completed by the NGOs specializing in child development and well-being research [21,26,27,28,45,46,47,48], as well as five reports provided by government-supported institutions [49,50,51,52,53]. In total, 23 studies are selected as references to identify relevant themes, subthemes and criteria. By including studies from an academic, organizational and governmental background, a more comprehensive set of themes can be identified. Based on the discussed rights and principles, a set of relevant themes related to SCD can be determined: health, safety, education and participation. Furthermore, by reviewing selected studies on CD and well-being, two additional themes are identified: relationships and economic status. Moreover, subthemes and according criteria associated with the themes are categorized as well. A comprehensive overview of all themes and subthemes and related criteria is displayed in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The numbers given in brackets of Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 refer to the frequency of their occurrence in the literature analyzed. Despite the limitations of this purely quantitative indicator, it is still used here as a proxy indicator for their relevance. The categorization presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 is reflected in the development of the SCDI by the introduction of two levels: an outcome level and a context level. The SCDI framework differentiates between subthemes that relate to the outcome of child development (outcome level, e.g., school attainment) and subthemes that relate to contexts that affect those outcomes (context level, e.g., parents’ educational qualifications) [41,54]. In the following, relevant themes, subthemes and criteria are discussed in more detail.

2.2.1. Health

According to the literature review, health is a theme of high importance for CD. Without securing their health, children have difficulties surviving and obtaining skills, and this negatively affects future human capital. In Table 3, the subthemes and criteria related to health are presented. Risk behavior, nutrition, child mortality, immunization coverage, eating and physical activity and subjective health are identified as the six most relevant subthemes.

- -

- Behavior of children that puts their health at risk needs to be evaluated. Tobacco and alcohol use are two criteria that are identified as relevant for determining the exposure to health hazards, especially for children of school age. In addition, adolescent fertility is also recognized as relevant, as it could damage the immature reproductive system and also increase the risk of venereal disease.

- -

- Sufficient nutrition is a basic need for children and their physical development. Low birth weight, being overweight and obesity, breastfeeding and being underweight are identified as relevant criteria for the subtheme nutrition.

- -

- Reducing child mortality was already suggested in the MDGs and is frequently mentioned in the literature. To determine child mortality, infant mortality and under-five mortality are two commonly suggested criteria.

- -

- Sufficient vaccination programs are representative of the quality of health services (to avoid particular harmful communicable diseases in children). Full immunization, vaccinations for diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) and vaccinations for measles (measles containing vaccine, MCV) are three criteria identified as relevant for evaluating the state of immunization of children.

- -

- Both physical activity and healthy diets help children to strengthen their physiological function. For example, healthy eating behaviors, like having breakfast and eating fruits, are two commonly recommended criteria in the literature.

- -

- Apart from judging health from an objective perspective, the subjective perspective is also relevant. Criteria such as satisfaction and perceived quality of life relate to the subjective health of children.

- -

- Other subthemes, such as oral health, injury, mental health, maternal health, health financing, water and sanitation, child disability, chronic disease and hazardous pollutants, are mentioned, but not frequently addressed in the reviewed literature. HIV and malaria are rarely considered in the reviewed literature, even though they can also affect health and are directly linked to the MDGs.

2.2.2. Education

Education is another theme of high relevance for SCD. Obtaining benefits from education, for example learning values, behavior, knowledge, skills and competencies required for a sustainable future, is a key pathway of SD [55]. This theme refers to the attainment of knowledge and skills, which is important for children to develop their capability to work and to elaborate life. By means of the literature review, several subthemes could be identified. As displayed in Table 4, school attainment, attendance of basic education, early childhood education and advanced education (high schools and colleges) are the subthemes with high priority for evaluating the educational background of children.

- -

- The subtheme school attainment can be evaluated by means of the criteria mathematical and reading literacy. Higher literacies indicate that children may have better performance and knowledge obtainment.

- -

- Several criteria are available for evaluating the level of basic education. This links to the MDG ‘achieving universal primary education’. During the literature review, enrollment in primary school is identified as the criteria most often used to assess whether children obtain basic and fundamental knowledge. However, gender equality is assessed only by one study in the literature. Unequal rights in basic education can seriously damage further skill development and also lead to the vicious circle of the situation of females.

- -

- Early childhood education and advanced education are two other subthemes essential to children. Early childhood education is important to attain day-to-day knowledge and to acquire social capability in the initial phases of life. The criteria ‘enrollment in kindergarten’ is identified as the most relevant to reflect the level of early childhood education. Advanced education refers to the attainment of higher levels of knowledge for further development of skills, which plays a key role to strengthen the position of children in the employment market.

- -

- Other subthemes mentioned as relevant for assessing the theme education are transition to employment, parents’ education qualification, other participation (like extra-curricular subjects) and public expenditure on education.

2.2.3. Safety

Children are fragile in the early life stage and need parents and adults to care for and support them. Without appropriate care arrangements, children can easily be exposed to dangers and engage in delinquent behavior. Violence and crime, child care arrangements and child abuse and punishment are identified as the three major subthemes of safety (see Table 5).

- -

- Violence in school and juvenile delinquency are identified as the two main criteria for evaluating safety in the literature review. Criteria presumed as relevant, like child trafficking, child prostitution and child pornography, are not evaluated in the currently reviewed literature. These situations occur especially in countries with insufficient laws [10,12].

- -

- Child abuse can cause physical and mental damage and, consequently, has a negative effect on CD.

- -

- Child care arrangement is relevant for ensuring the safety of children. The identified criteria are formal care and adult supervision after school.

- -

- Governmental efforts to ensure child safety, like birth registration, child labor, child marriage, and female genital mutilation (FGM).

2.2.4. Relationships

Relationships with family, peers and community are identified as common subthemes in the literature for the evaluation of child development, as shown in Table 6. Effective relationships are important for children with regard to their long-term emotional and psychological development [28]. Family relationships provide the basis for children’s personality and behavior; peers and community relationships also shape CD as external factors. Communication between parents and children, as well as family structure (such as single-parent or step families) are the two main criteria reflecting the family relationship. They are typically based on subjective evaluations. However, these criteria are mainly included in studies from industrialized countries [26,27,28,35,36,38,40,48,49,50,52,53,56].

2.2.5. Economic Status

Economic status is another theme identified as relevant for the assessment of CD. The main subthemes are relative household income poverty, household without job, material deprivation, risk housing, hunger and food shortage, crowded household and macroeconomic situation (see Table 6). Those subthemes influence children from a material perspective and can affect their daily life. If the resources of income, material and housing are not sufficient, CD can be restricted, possibly triggering the early leave from school and possible crimes.

2.2.6. Participation

Participation is not widely discussed in most of the reviewed literature. However, based on the importance for children to learn how to express their opinions on public issues, participation is identified as a relevant theme. Participation in public affairs via voting, joining civic activities and engaging in media can motivate children to defend their rights and become responsible and active citizens. The voting right is a key for children to express their choices in politics and public affairs.

However, there are several potential subthemes that have not been addressed in the reviewed literature, but that might be of high importance for SCD. In the next section, gaps of current SCD, such as inconsistent definitions of the age of children, heterogeneous classification of subthemes and criteria, potential bias in addressing certain aspects, the limited number of subthemes and criteria and the missing consideration of environmental aspects, are discussed. Furthermore, based on these gaps, additional subthemes are identified for the development of the SCDI.

Table 3.

Subthemes and related criteria of the theme health in current child development (CD) studies.

| Health (23) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Risk behavior (21) | Nutrition (19) | Child mortality (18) |

|

|

|

| Immunization coverage (15) | Eating and physical activity (12) | Oral health (9) |

|

|

|

| Subjective health (12) | Injury (8) | |

|

| |

| Mental health (8) | Maternal health (7) | Health financing (6) |

|

|

|

| Child disability (5) | ||

| Chronic disease (5) | ||

| Accessibility of health service (3) | ||

| Hazardous pollutant (4) | Water and sanitation (3) | HIV (3) |

|

|

|

| Malaria (2) | School absence due to health issues (2) | Activity limitation (2) |

| Child cancer (2) | Diabetes (1) |

| Diarrhea (2) | Hearing (1) | |

| Asthma (2) | Chlamydia infection (1) | |

| Pneumonia (2) | ||

The numbers in brackets display the times considered in the literature.

Table 4.

Subthemes and related criteria of the theme education in current child development (CD) studies.

| Education (23) | ||

|---|---|---|

| School attainment (18) | Early childhood education (12) | Attendance of advanced education (11) |

|

|

|

| Attendance of basic education (10) | Subjective evaluation (9) | Parent’s educational qualification (5) |

|

|

|

| Transition to employment (7) | Other participation (4) | |

|

| |

| Public expenditure on education (2) | ||

The numbers in brackets display the times considered in the literature.

Table 5.

Subthemes and related criteria of the theme safety in current child development (CD) studies.

| Safety (19) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Violence and crime (14) | Child care arrangement (8) | Child abuse (6) |

|

| Birth registration (2) |

| Child labor (2) | ||

| Child marriage (2) | ||

| Physical punishment (4) | Female genital mutilation (2) | |

| ||

The numbers in brackets display the times considered in the literature.

Table 6.

Subthemes and related criteria of the theme economic status, relationship and participation in current child development (CD) studies.

| Economic status (19) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Relative household income poverty (16) | Household without job (9) | Macroeconomic situation (3) |

| Material deprivation (8) | Risk housing (8) |

|

| Food shortage (5) | |

| Crowded household (4) | ||

| Debt and financial difficulties (2) | ||

| Worry about family financial situation (2) | ||

| Relationship (17) | ||

| Family relationship (17) | Peer relationship (8) | Community relationship (8) |

|

|

|

| Participation (6) | ||

| Participation in civic activity (4) | Social connection (3) | Voting in presidential elections (3) |

| ||

The numbers in brackets display the times considered in the literature.

2.3. Gaps and Challenges of Assessing CD

As an additional contribution of the literature review, several gaps were identified with regard to the current analysis of CD. The inconsistent definitions of the age of children considered, the heterogeneous classification of subthemes and criteria, interdependency, regional and societal bias in addressing certain aspects, the limited subthemes and criteria and the lack of including environmental aspects currently impede the implementation of SCD.

2.3.1. Inconsistent Definitions of the Age of Children

This study follows the definition of the United Nations’, stating that children are people under 18 years old [10]. However, this definition is not uniformly applied throughout studies. For example, the Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion states that the definition of “children” encompasses only people from age two to less than 12, and refers to “teenager” from age 12–20 [57]. In addition, other studies consider the criterion “risk behavior” of children at different ages, for instance surveying the tobacco use at age 16 or 18 [27,28,36,49,52,57]. This may bring about inconsistencies in the data used for further evaluation.

2.3.2. Heterogeneous Classification of Relevant Aspects

The clustering of subthemes and criteria is not a straightforward task. The literature review revealed that the classification of criteria and subthemes is rather heterogeneous and that there is currently no generally accepted classification scheme [32,38,58,59]. There are discrepancies in the literature with regard to the identification of relevant themes, subthemes and criteria. The choice of themes, subthemes and criteria is subjective and depends also on the availability of related data [38,41]. Furthermore, different approaches for addressing certain themes are used. For example, the theme education can be approached by evaluating the subtheme school attainment or the subtheme attendance of basic education [59]. Thus, this paper proposes a consistent classification scheme based on existing literature (see Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6).

2.3.3. Interdependencies

So far, an assessment of the dependencies between different subthemes and criteria is missing [54]. Even though the SCDI framework is a first step towards a standardized and explicit classification scheme, the interdependencies between the criteria and subthemes needs to be further investigated in future studies. Furthermore, the attribution of criteria to the different subthemes is often ambiguous. The criterion low birth weight currently attributed to the subtheme nutrition could also be used as a criterion for analyzing maternal health.

2.3.4. Regional and Societal Bias

Current studies often lack a truly global perspective and, thus, underrepresent aspects of high relevance for CD in certain regions. The identification of subthemes and criteria is often based on the concerns of industrialized countries. In addition, some criteria are based on particular societal preferences in evaluating CD. Both effects introduce bias to CD assessment:

- -

- Only two studies cover the situation in developing countries [46,47]. So far, not enough attention is put on issues of particular relevance for developing countries, such as hunger, access to water, sanitation, malaria, diarrhea, etc. As a consequence, the criterion “overweight and obesity” is associated with higher attention in the current literature than the criterion “underweight”. Furthermore, access to water is generally assured, and sanitation systems are available in industrialized countries, leading to the negligence of those criteria in many studies. In addition, malaria and diarrheal disease, which are very critical to young children, receive little attention in the reviewed literature [47], as they mainly occur in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- -

- FGM for non-medical reasons violates the human rights of girls and causes severe damage to health. However, as FGM occurs mainly in Africa and the Middle East, insufficient attention is paid to it in current literature [46,47].

- -

- Societal preferences lead to criteria like the proportion of children living in single-parent families and stepfamilies, which is often used to negatively judge family relationship. However, children in single-parent and stepfamilies can still grow up well [28]. Similarly, regarding child labor, usually negative impacts, like increasing health risks and deteriorating school performance, are mentioned and observed; however, some positive effects, like the development of discipline, responsibility and self-confidence, may also occur [60]. It is very complicated to establish straightforward cause and effect relations with regard to CD due to the multi-faceted character of social issues.

For a holistic assessment of CD, subthemes and criteria need to also acknowledge such regional and societal circumstances. The evaluation framework needs to be designed in a way that allows customization and expansion for different regional and societal preferences.

2.3.5. Limited Subthemes and Criteria

There are still some general issues that may affect CD, but lack proper consideration in the scientific literature. Examples include vocational education, equality in education, demographic structure, youth unemployment or availability of media for children. Those missing issues highlight that current CD studies are still confined to limited sets of themes, subthemes and criteria.

2.3.6. Lack of Including Environmental Aspects

Current CD studies focus mainly on social and economic issues. Environmental aspects are not addressed yet. However, environmental aspects need to be addressed as an additional theme to link CD to SD with triple-bottom-line thinking (considering environmental, economic and social aspects) [7] and protecting inter-generational equity. Some studies related to human or society development already pointed out the relevance of environmental aspect for SD [2,8,18,19]. In existing studies, there are only two proposals to consider greenhouse gas emission, and only two studies indicated the potential relevance of other environmental issues, such as the use of renewable energy and water resources, etc. [2,8,18,19]. The effects of greenhouse gas emissions occur on a global level. For assessing CD regional effects, it would be of higher interest to assess the difference between countries. Regional issues related to the exhaustion and scarcity of resource, like water vulnerability and the use of renewable energy, should be considered in SCD. In the next section, the SCDI framework is outlined to address the identified gaps and to support a more comprehensive approach for the assessment of SCD.

3. The Sustainable Child Development Index

Based on the literature review and the identified themes, subthemes and criteria, a new concept is proposed: The Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). The SCDI aims to provide a consistent and comprehensive assessment of CD from a sustainability perspective and to address existing gaps by identifying subthemes and criteria according to their relevance, distinguishing between an outcome and context level, considering regional conditions and including environmental aspects.

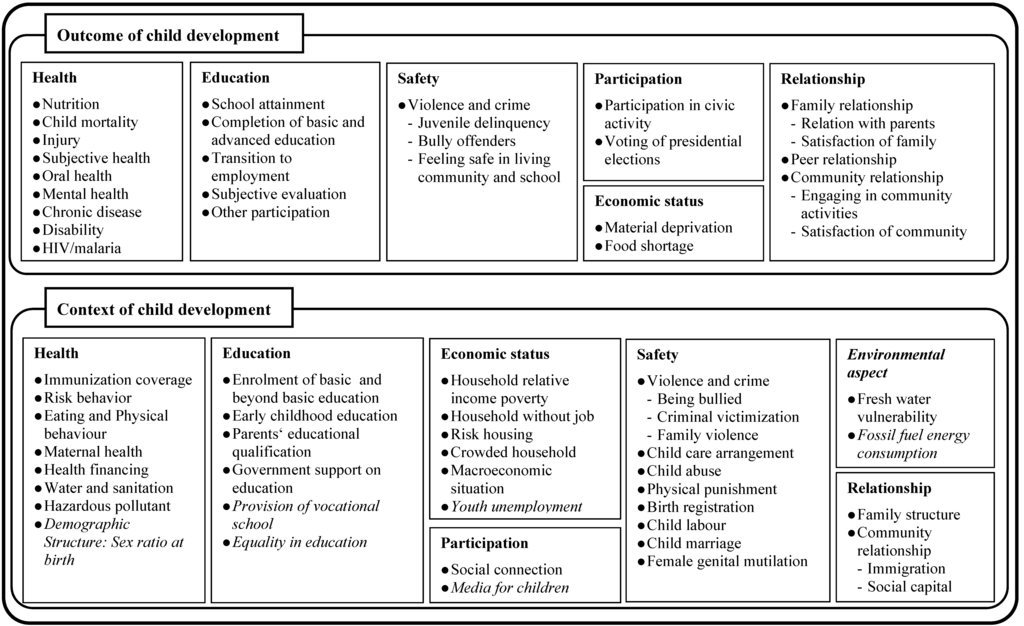

An integration of sustainability aspects, especially environmental aspects, is needed to acknowledge the connection between present and future generations [8]. Among various concepts of sustainability, the triple-bottom-line theory is widely adopted, especially in politics, as it considers environmental, economic and social aspects as outlined in LCSA [14]. This triple-bottom-line theory is also adopted in the SCDI framework to demonstrate the relationship of CD and sustainability thinking. The three dimensions are partially overlapping and correlate with each other. In Figure 1, the themes identified in the SCDI are assigned to the corresponding dimension of sustainability to highlight the consideration of all three dimensions of sustainability.

The SCDI is proposed as a two-level scheme, including an outcome and a context level. Both levels rely on the six earlier identified themes: health, education, safety, economic status, relationships and participation as a foundation and include the additional theme environment on the context level to live up to the requirements of sustainability. The outcome level refers to the development status of children, like child mortality and school attainment, including subthemes identified in the literature review. The context level considers aspects, such as relative family income, that can affect the outcomes of CD. This context level also includes aspects that have not been addressed in current literature (e.g., demography), but that are considered as relevant for achieving a comprehensive assessment of SCD.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI) structure based on the triple-bottom-line theory.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI) structure based on the triple-bottom-line theory.

As there is no generic agreement with regard to approaches and themes to be considered in CD studies, a framework is needed to broadly distinguish the subthemes and criteria in two parts: outcomes of CD and contexts that have the potential to influence the outcomes [32,41,54,61]. The contextual subthemes and criteria can affect CD, but this causal relationship is not binding. For instance, growing up in a single-parent family may, but does not necessarily have to increase the likelihood of having negative effects on CD. This implies that the contextual subthemes and criteria are associated with the outcome of CD, but should not be considered as direct measures of the outcome [54]. In this sense, on the outcome level, the subthemes showing children’s status and capability are selected based on the results of Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. For example, the subthemes nutrition, child mortality, injury, subjective health, oral health, mental health, chronic disease and disability are listed on the outcome level of the theme health in line with the literature review.

Furthermore, the additional theme environmental aspect is added on the context level to bridge current CD to SD and to highlight the relevance of the triple-bottom-line thinking. Based on the definitions of environment, resource accessibility is identified as relevant and needs to be considered in the development of the SCDI framework. A similar concept was also introduced in a proposal for the Sustainability Adjusted HDI (SHDI) [8]. The SHDI proposes to include, for instance, fresh water withdrawals, land use for permanent crops, biodiversity lost and greenhouse gas emissions into the evaluation of human development. For assessing SCD, freshwater vulnerability is proposed as a subtheme of the theme environmental aspects due to the close relation to everyday needs of children, the regional and local circumstances and the relevance to maintaining freshwater access for the achievement of inter-generational equity. The criterion hazardous pollutants is not considered under the theme environment aspects, as it is included under the theme health, in line with current literature.

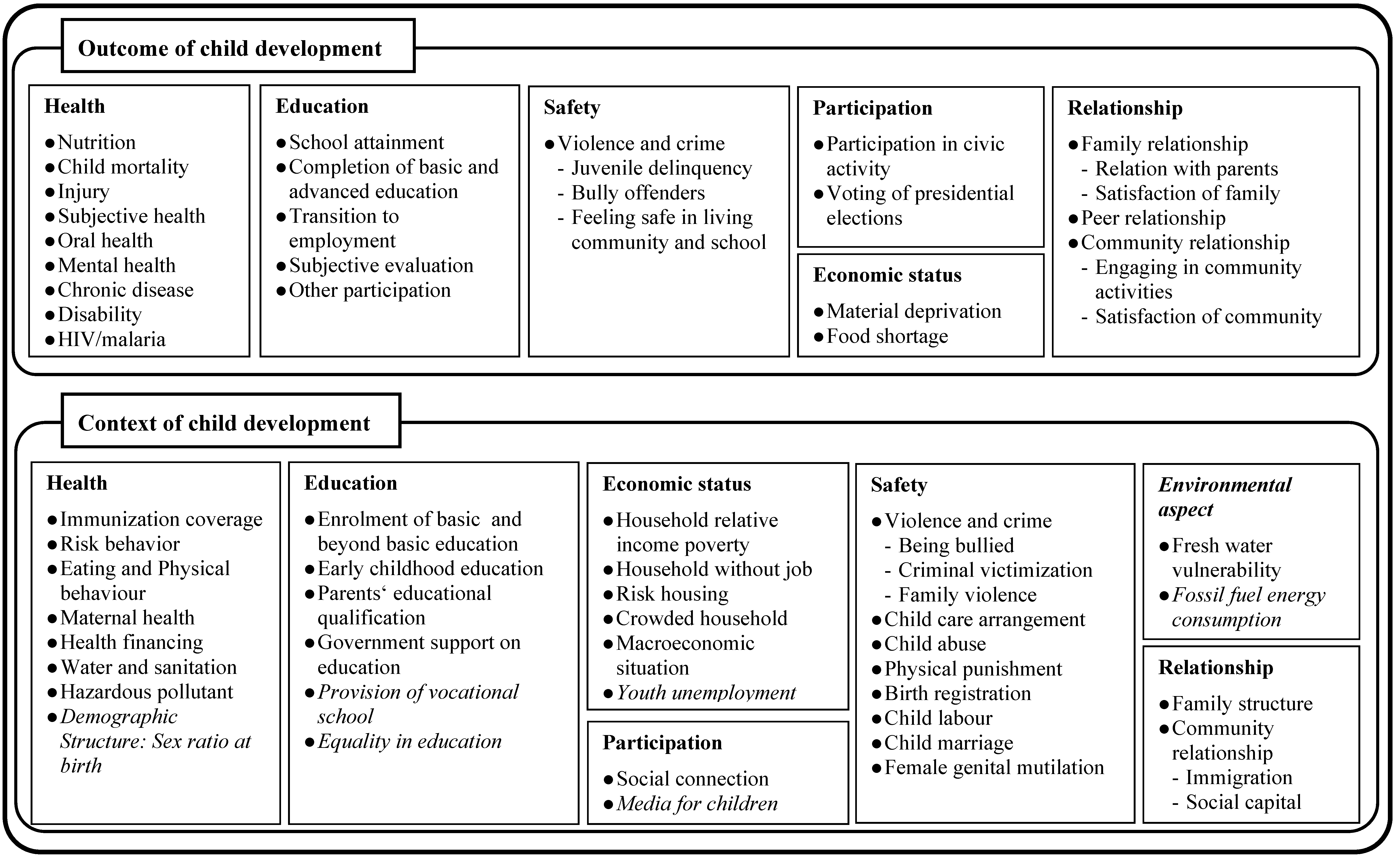

On the context level, subthemes that have the potential to influence the outcome of CD are selected. In addition, new subthemes are proposed based on the gap analysis to strengthen the comprehensiveness of the evaluation. These subthemes include provision of vocational school, equality in education, youth unemployment, availability of media for children, fossil fuel energy consumption and demographic structure. An overview of the outcome and context level proposed in this work is provided in Figure 2. The new subthemes are written in italics in Figure 2 and are described as follows.

- -

- Vocational education (may include technical schools, workshop schools, development agencies, etc. [55]) is designed to prepare individuals for a vocation or a specialized occupation and is directly linked with a nation’s productivity, competitiveness and equality in education. It can increase further career development opportunities and professional status [62]. Quality of life of children and personal development, attitudes and motivation can also be affected by vocational education.

- -

- Equality in education is essential for all children. Gender equality in education plays a core role in protecting children’s basic right to education. If gender equality is low, this leads to a vicious circle in the further personal development of girls, human capital and gender conflicts in society.

- -

- The global youth unemployment rate in 2013 was 12.6%, close to a crisis critical peak [63]. Although children are defined as aged 0–18 earlier, youth (aged 15–24) unemployment can reflect the prosperity of job opportunities and can influence children’ plans for further education, career and development of skills. The economic and social costs of unemployment and widespread low quality jobs for young people continue to rise and undermine the potential of economies to grow [63].

- -

- Media (newspapers, periodicals, books, broadcasts, websites, television shows and news, etc.) designed for children is important for children to attain knowledge and to participate in public affairs by expressing their opinions. Furthermore, well-designed media can provide information without harmful content, such as violence and pornography.

- -

- Fossil fuel is a non-renewable energy source. High fossil fuel energy consumption speeds up the depletion of fossil fuel resources and damages the rights of future generation to access these resources. Each country should reduce the consumption of fossil fuel and should implement measurements to promote renewable energy.

- -

- Demographic structure (especially the sex ratio at birth, estimated as the number of boys born per 100 girls) can reflect the attitude towards gender equality in society. High sex ratios at birth may be attributed to sex-selective abortion, infanticide and underreporting of female births due to a strong preference for sons [64,65]. Exposure to pesticides and other environmental contaminants may be a significant contributing factor, as well.

Furthermore, a comprehensive assessment of SCD needs to enable the inclusion of additional subthemes into the assessment that might be only of regional relevance. The necessity of adapting to the circumstances in, for example, developing countries can be considered on both levels by including subthemes related to societal value and prerequisites in the SCDI, which can be adapted according to country-specific situations. These subthemes can refer to FGM, armed conflicts or critical diseases, for example HIV or malaria (see also the previous section).

By proposing a set of themes and subthemes and by differentiating the assessment into an outcome and context level, the SCDI can enable a comprehensive evaluation of SCD. Though the arrangement of the subthemes into the two different levels can be debated with regard to different approaches developed among CD-related studies and there are still potential missing issues not addressed in the index, the SCDI is a first step towards a common and consistent assessment of CD in the context of sustainable development.

To further develop the SCDI, as a next step, relevant criteria need to be identified that properly represent the identified subthemes, and the quantification of these criteria for the calculation of the numerical SCDI needs to be defined. The goal is to provide quantitative values to compare the performance of countries and to reflect their potential toward SD. The SCDI can then be used to support decision making in policy and societal development and bridge SCD to current sustainability studies.

In addition to its application on the country level, the SCDI framework intends to complement SLCA methodologies as part of LCSA. SCDI could be used to fill the current gap of SLCA and to introduce children as an additional stakeholder group in SLCA, respectively LCSA. As SLCA is struggling with lacking data, children could even replace the current stakeholder groups for a high-level assessment, and SCDI could provide the basis for an indicator framework.

Figure 2.

The structure of the Sustainable Child Development Index.

Figure 2.

The structure of the Sustainable Child Development Index.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

The study provides a new approach by treating children as the critical stakeholder group for SD, since they represent the link between current and future generations. In a comprehensive literature review, six relevant themes were identified, which need to be considered for assessing SD of children: health, education, safety, economic status, relationships and participation. Several relevant subthemes were identified and clustered correspondingly. Nevertheless, there are still critical gaps in current studies on CD, such as the lacking environmental aspect, biased perspectives in identifying critical issues and the correlation between themes. Based on these findings, the two-level Sustainable Children Development Index (SCDI) framework is proposed to comprehensively consider relevant themes and subthemes of sustainable child development in an outcome and a context level, but beyond current practices by including additional aspects. By including environmental aspects and enabling the integration of additional aspects with regional relevance, the SCDI enables the evaluation of the potential towards SD at a country level. The SCDI can be applied to support decision making in policy and be used to support decision making in policy and societal development.

However, several shortcomings remain. The relevant themes, subthemes and criteria considered in this paper depend on the reviewed literature. Thus, the proposed scheme will have to be revised when additional literature and information with regard to CD become available. Furthermore, the interdependencies between the different subthemes and criteria need to be discussed in more detail in future studies, as these interdependencies could influence the categorization of the criteria. Since CD aspects are often multi-faceted with complex and indirect cause-and-effect relations, interpretation is not always straightforward. This will be addressed in more detail in the future, and the SCDI will be tested in exemplary case studies. This study adopts triple-bottom-line thinking to construct the framework of SCDI; however, the definitions of sustainability are diverse and can influence the understanding of the integrated SCDI framework. This needs to be considered for interpretation and further developments of the SCDI.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge that the research presented here is partly funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) as part of the project “Methodische Nachhaltigkeitsbewertung von Maschinenkomponenten im Entwicklungsprozess” and the Collaborative Research Center CRC1026 (Sonderforschungsbereich SFB1026).

Author Contributions

Ya-Ju Chang is the leading composer of the manuscript. The research, including literature analysis and new method development, was completed and proposed by Ya-Ju Chang. Laura Schneider and Matthias Finkbeiner both provided substantial contributions to the design of the study. All authors proofread and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed on 11 January 2014).

- Van de Kerk, G.; Manuel, A. Sustainable Society Index 2012; Sustainable Society Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K. The sustainable development area: Satisfying basic needs and safeguarding ecological sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable development: A bird’s eye view. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Glossary of Environment Statistics; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations; European Commission; International Monetary Fund; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Bank. Handbook of National Accounting: Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting 2003; World Bank: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, N.; Maas, R.; Goralcyk, M.; Wolf, M.-A. Towards a Life-Cycle Based European Sustainability Footprint Framework; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J.; United Nations Development Programme. Sustainability and Human Development: A Proposal for a Sustainability Adjusted HDI (SHDI); Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Münich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource; United Nations Environment Programme; World Wildlife Fund. World Conservation Strategy—Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development; International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource: Gland, Switherland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Rights of the Child; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of the child. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 11 July 2014).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. A Post-2015 World Fit for Children—Sustainable Development Starts and Ends with Safe, Healthy and Well-Educated Children; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halleröd, B.; Rothstein, B.; Daoud, A.; Nandy, S. Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2013, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Schau, E.M.; Lehmann, A.; Traverso, M. Towards life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Towards a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment-Making Informed Choices on Products; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. The Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; United Nations Environment Programme: Druk in de weer, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Human Development Report 2013: Human Progress in a Diverse World; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao-Ubillos, J. The limit of human develoment idex: The complementary role of economic and social cohesion, development strategies and sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togtokh, C.; Gaffney, O. 2010 Human Sustainable Development Index. Available online: http://ourworld.unu.edu/en/the-2010-human-sustainable-development-index (accessed on 17 March 2014).

- Morse, S. Bottom rail on top: The shifting sands of sustainable development indicators as tools to assess progress. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2421–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children Fund. The Child Development Index 2012—Progress, Challenges and Inequality; Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children Fund. The child Development Index—Holding Governments to Account Children’s Wellbeing; Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. From child welfare to children well-being: The child indicators perspective. In From Child Welfare to Child Well-Being—An International Perspective on Knowledge in the Service of Policy Making; Kamerman, S.B., Phipps, S., Ben-Arieh, A., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. The child indicators movement: Past, present, and future. Child Indic. Res. 2008, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children’s Society. The Good Childhood Report 2013; Children’s Society: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Child Development. Child and Youth Well-Being Index (CWI); Foundation for Child Development: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries; United Nations Children’s Fund: Florence, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Child Rights and You. Child rights. Available online: http://www.cry.org/CRYCampaign/ChildRights.htm (accessed on 9 October 2013).

- Child Rights International Network. Child right themes. Available online: http://www.crin.org/en/home/rights/themes (accessed on 11 January 2014).

- United Nations. United nations millennium declaration. Available online: http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm (accessed on 2 April 2014).

- Minkkinen, J. The structural model of child well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P.R.; Ulkuer, N. Child development in developing countries: Child rights and policy implications. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme. The millennium development goals—Eight goals for 2015. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview/ (accessed on 2 April 2014).

- Lee, B.J.; Kim, S.S.; Ahn, J.J.; Yoo, J.P. Developing an Index of Child Well-Being in Korea. In Proceedings of the 4th International Society of Child Indicators Conference, Seoul, Korea, 29–31 May 2013.

- Niclasen, B.; Köhler, L. National indicators of child health and well-being in Greenland. Scan. J. Public Health 2009, 37, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L. A Child Health Index for the North-Eastern Parts of Göteborg; Nordic School of Public Health: Göteborg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.Y.-N. A clustering approach to comparing children’s wellbeing accross countries. Child Indic. Res. 2014, 7, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbstein, N.; Hartzog, C.; Geraghty, E.M. Putting youth on the map: A pilot instrument for assessing youth well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; Hoelscher, P.; Richardson, D. An index of child well-being in the european union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 133–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J. Mapping domains and indicators of children’s well-being. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2797–2805. [Google Scholar]

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S. Conceptual and methodological foundations of the child and youth well-being index. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-Being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafin, S.; Brooks, A.-M.; Carroll, E.; Fitzgerald, E.; GaBhainn, S.N.; Sixsmith, J. Achieving consensus in developing a national set of child well-being indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S.; Zheng, H.; Fu, Q. The CWI and its components: Empirical studies and findings. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Mbwana, K.; Theokas, C.; Lippman, L.; Bloch, M.; Vandivere, S.; O’Hare, W. Child Well-Being: An Index Based on Data of Individual Children; Child Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2014 in Numbers: Every Child Counts; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Childinfo: Monitoring the situation of children and women. Available online: http://www.childinfo.org/ (accessed on 11 March 2014).

- Mather, M.; Dupuis, G. The New Kids Count Index; The Annie E. Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development. Children and Young People: Indicators of Wellbeing in New Zealand 2008; Ministry of Social Development: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Headline Indicators for Children’s Health, Development and Wellbeing 2011; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- European Union Community Health Monitoring Programme. Child Health Indicators of Life and Development; European Union Community Health Monitoring Programme: Luxemburg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being 2013; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Social Determinants of Health and Well-Being among Young People; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Murphey, D.; Bandy, T.; Lawner, E. Indices of child well-being and developmental contexts. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2807–2822. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Menoyo, M.Á. Educating for local development and global sustainability: An overview in spain. Sustainability 2009, 1, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L. Municipal indicators for children’s health in Sweden. In Proceedings of the 1st International Society of Child Indicators Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 June 2007.

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. Measuring the Health of Infants, Children and Youth for Public Health in Ontario: Indicators, Gaps and Recommendations for Moving Forward; Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare, W.P.; Gutierrez, F. The use of domains in constructing a comprehensive composite index of child well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2012, 5, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arieh, A.; Casas, F.; Frønes, I.; Korbin, J.E. Multifaceted concept of child well-being. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, A.; Lai, L.C.H.; Hauschild, M.Z. Assessing the validity of impact pathways for child labour and well-being in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, V.L.; Land, K.C. Methodologies used in the construction of composite child well-being indices. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2739–2755. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. The Benefits of Vocational Education and Training; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2013; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. Report of the International Workshop on Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth; United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswar, J. Population perspectives and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2000, 8, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).