Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Seasonal dependence: it began in winter in the northern hemisphere and both case and death rates were lowest in summer, especially in Europe, and rates began increasing again in July, August, or September in various European countries [10]; it is thus generally inversely correlated with solar UVB doses and vitamin D production [11,12].

- Much of the damage from COVID-19 is thought to be related to the “cytokine storm”, which is manifested as hyperinflammation and tissue damage [16].

- The body’s immune system becomes dysregulated in severe COVID-19 [17].

2. Findings Regarding Vitamin D and COVID-19

2.1. Vitamin D Deficiency Increases the Risk and Severity of COVID-19

2.2. Vitamin D and Treatment of COVID-10

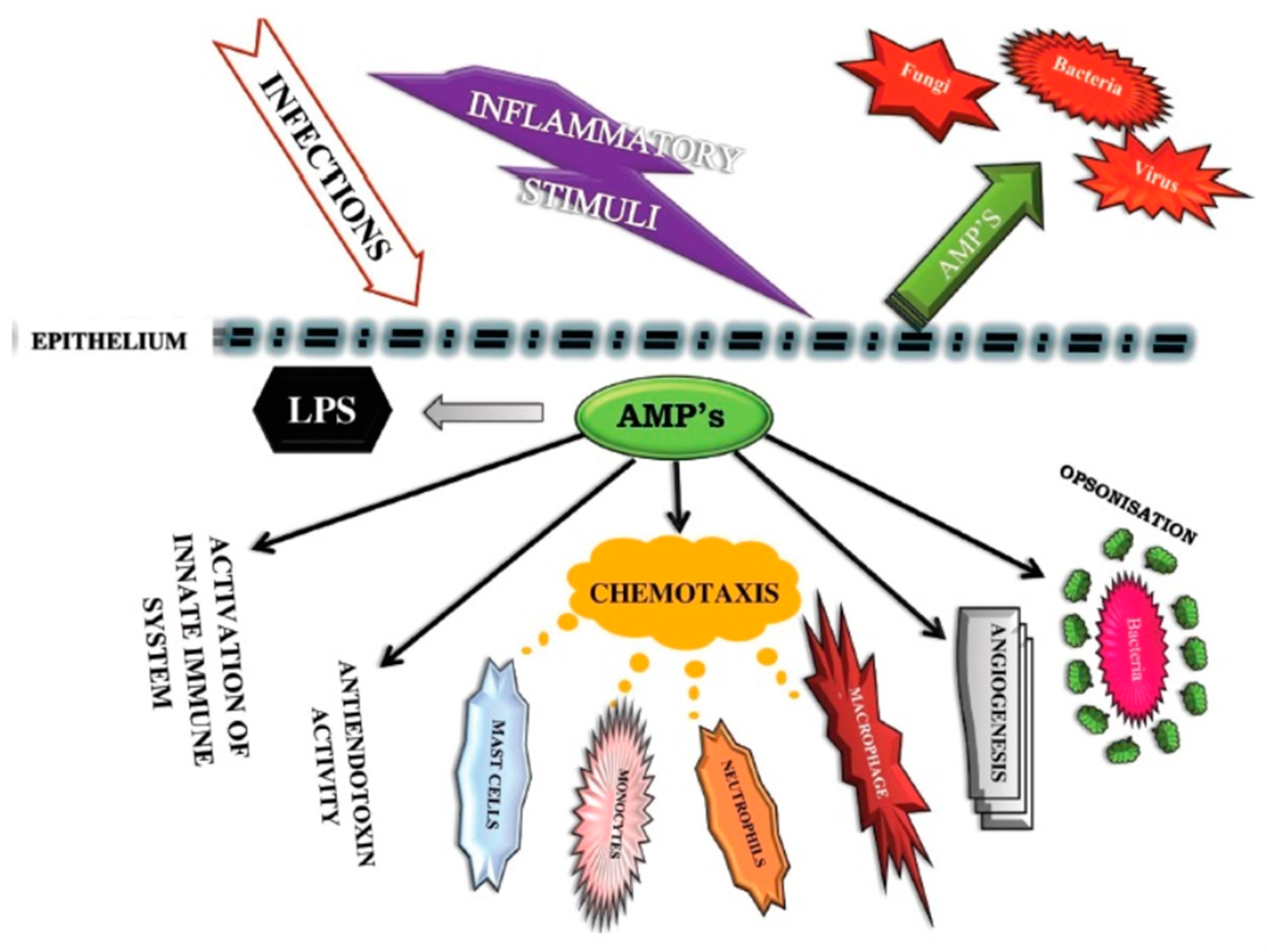

2.3. Vitamin D Helps Immune Cells Produce Antimicrobial Peptides

2.4. Vitamin D Reduces Inflammatory Cytokine Production

2.5. Type II Pneumocytes and Surfactants in the Lungs

2.6. Vitamin D, Angiotensin II, and ACE2 Receptors

2.7. Reduces Risk of Endothelial Dysfunction

2.8. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9

2.9. RAS-Mediated Bradykinin Storm

2.10. Summary: How Vitamin D Might Reduce Risk, Severity, and Death from COVID-19

- Inactivates some viruses by stimulating antiviral mechanisms such as antimicrobial peptides, as discussed in Section 2.3.

- Reduces proinflammatory cytokines through modulating the immune system, as discussed in Section 2.4.

- Increases ACE2 concentrations and reduces risk of death from ensuing ARDS, as discussed in Section 2.5.

- Reduces risk of endothelial dysfunction, as discussed in Section 2.7.

- Reduces MMP-9 concentrations, as discussed in Section 2.8.

- Reduces risk of the bradykinin storm, as discussed in Section 2.9.

2.11. Vitamin D Seasonality and COVID-19

2.12. Racial/Ethnic Disparities

2.13. Vitamin D Reduces Risk of COVID-19 in a Causal Manner

2.14. Other Nutrients That May Augment the Effectiveness of Vitamin D Supplementation

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chibuzor, M.T.; Graham-Kalio, D.; Osaji, J.O.; Meremikwu, M.M. Vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD012581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, D.K.; Yin, K. Vitamin D and inflammatory diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2014, 7, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Panfili, F.M.; Roversi, M.; D’Argenio, P.; Rossi, P.; Cappa, M.; Fintini, D. Possible role of vitamin D in Covid-19 infection in pediatric population. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C. Vitamin D Signaling in the Context of Innate Immunity: Focus on Human Monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manson, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.M.; Christen, W.; Bassuk, S.S.; Mora, S.; Gibson, H.; Gordon, D.; Copeland, T.; D’Agostino, D.; et al. Vitamin d supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B.; Al Anouti, F.; Moukayed, M. Targeted 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration measurements and vitamin D3 supplementation can have important patient and public health benefits. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittas, A.G.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Sheehan, P.; Ware, J.H.; Knowler, W.C.; Aroda, V.R.; Brodsky, I.; Ceglia, L.; Chadha, C.; Chatterjee, R.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Greenberg, L.; Aloia, J.F.; Bergman, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Esposito, S.; Ganmaa, D.; Ginde, A.A.; Goodall, E.C.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: Individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2019, 23, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.E.; Ntambi, J.M. Multiple Sclerosis: Lipids, Lymphocytes, and Vitamin D. Immunometabolism 2020, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Mitri, J.; Muraru, M.D.; Pittas, A.G. Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kroll, M.H.; Bi, C.; Garber, C.C.; Kaufman, H.W.; Liu, D.; Caston-Balderrama, A.; Zhang, K.; Clarke, N.; Xie, M.; Reitz, R.E.; et al. Temporal Relationship between Vitamin D Status and Parathyroid Hormone in the United States. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancy, C.W. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA 2020, 323, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yehia, B.R.; Winegar, A.; Fogel, R.; Fakih, M.; Ottenbacher, A.; Jesser, C.; Bufalino, A.; Huang, R.-H.; Cacchione, J. Association of Race With Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US Hospitals. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2018039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginde, A.A.; Liu, M.C.; Camargo, C.A. Demographic Differences and Trends of Vitamin D Insufficiency in the US Population, 1988-2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caricchio, R.; Gallucci, M.; Dass, C.; Zhang, X.; Gallucci, S.; Fleece, D.; Bromberg, M.; Criner, G.J. Preliminary predictive criteria for COVID-19 cytokine storm. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Studies for Vitamin D, Covid19. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=COVID19&term=vitamin+D&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- VanderWeele, T.J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, W.B.; McDonnell, S.L. Statistical error in Vitamin d concentrations and covid-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 893–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.S.; Matson, M.; Herlekar, R. Response to ‘vitamin d concentrations and covid-19 infection in uk biobank’. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Mackay, D.F.; Ho, F.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Jani, B.D.; Welsh, P.; Mair, F.S.; Gray, S.R.; et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avolio, A.; Avataneo, V.; Manca, A.; Cusato, J.; De Nicolo, A.; Lucchini, R.; Keller, F.; Cantu, M. 25-hydroxyvitamin d concentrations are lower in patients with positive pcr for sars-cov-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotou, G.; Tee, S.A.; Ihsan, Y.; Athar, W.; Marchitelli, G.; Kelly, D.; Boot, C.S.; Stock, N.; Macfarlane, J.; Martineau, A.R.; et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 are associated with greater disease severity: Results of a local audit of practice. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Di Lecce, V.; Quaranta, V.N.; Zito, A.; Buonamico, E.; Capozza, E.; Palumbo, A.; Di Gioia, G.; Valerio, V.N.; Resta, O. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.H.; Je, Y.S.; Baek, J.; Chung, M.H.; Kwon, H.Y.; Lee, J.S. Nutritional status of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karonova, T.L.; Andreeva, A.T.; Vashukova, M.A. Serum 25(Oh)D Level in Patients with Covid-19. J. Infectol. 2020, 12, 21–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.A.R.; Nieto, A.V.P.; Martínez-Cuazitl, A.; Mercado, E.A.M.; Tort, A.R. La deficiencia de vitamina D es un factor de riesgo de mortalidad en pacientes con COVID-19. Rev. Sanid. Mil. 2020, 74, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baktash, V.; Hosack, T.; Patel, N.; Shah, S.; Kandiah, P.; Abbeele, K.V.D.; Mandal, A.K.J.; Missouris, C.G. Vitamin D status and outcomes for hospitalised older patients with COVID-19 2020. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Pell, J.P.; Sattar, N. Vitamin D and COVID-19 infection and mortality in UK Biobank. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radujkovic, A.; Hippchen, T.; Tiwari-Heckler, S.; Dreher, S.; Boxberger, M.; Merle, U. Vitamin D Deficiency and Outcome of COVID-19 Patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcour, A.; Blocki, F.; Hawkins, D.M.; Rao, S.D. Effects of Age and Serum 25-OH-Vitamin D on Serum Parathyroid Hormone Levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3989–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzini, A.; Aichner, M.; Sahanic, S.; Böhm, A.; Egger, A.; Hoermann, G.; Kurz, K.; Widmann, G.; Bellmann-Weiler, R.; Weiss, G.; et al. Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on COVID-19—A Prospective Analysis from the CovILD Registry. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaya, F.; Paeres, C.E.; Valls, A.; Fernández-Ortiz, A.; Del Castillo, J.G.; Martín-Sánchez, J.; Runkle, I.; Herrera, M.; Ángel, R. Interaction between age and vitamin D deficiency in severe COVID-19 infection. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Tang, F.; Liao, X.; Shaw, B.A.; Deng, M.; Huang, G.; Qin, Z.; Peng, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, C.; et al. Does Serum Vitamin D Level Affect COVID-19 Infection and Its Severity?-A Case-Control Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzon, E.; Tworowski, D.; Gorohovski, A.; Vinker, S.; Cohen, A.G.; Green, I.; Morgenstern, M.F. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 infection: An Israeli population-based study. FEBS J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.O.; Best, T.J.; Zhang, H.; Vokes, T.; Arora, V.; Solway, J. Association of Vitamin D Status and Other Clinical Characteristics with COVID-19 Test Results. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.W.; Niles, J.K.; Kroll, M.H.; Bi, C.; Holick, M.F. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.M. A brief review of interplay between vitamin D and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: Implications for a potential treatment for COVID-19. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, 30, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin d: What dietetics practitioners need to know. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Fischer, W.M.; Gnanakaran, S.; Yoon, H.; Theiler, J.; Abfalterer, W.; Hengartner, N.; Giorgi, E.E.; Bhattacharya, T.; Foley, B.; et al. Tracking changes in sars-cov-2 spike: Evidence that d614g increases infectivity of the covid-19 virus. Cell 2020, 182, 812–827.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, O.L.; Powell-Young, Y.; Reyes-Miranda, C.; Alzaghari, O.; Giger, J.N. African-americans have a higher propensity for death from covid-19: Rationale and causation. J. Natl. Black Nurses Assoc. 2020, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Autier, P.; Boniol, M.; Pizot, C.; Mullie, P. Vitamin D status and ill health: A systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autier, P.; Mullie, P.; Macacu, A.; Dragomir, M.; Boniol, M.; Coppens, K.; Pizot, C.; Boniol, M. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on non-skeletal disorders: A systematic review of meta-analyses and randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Guidelines for optimizing design and analysis of clinical studies of nutrient effects. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 72, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Lahore, H. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orkaby, A.R.; Djousse, L.; Manson, J.E. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2019, 34, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Niu, W. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on vitamin D supplement and cancer incidence and mortality. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, M.C.; Furlanetto, T.W. Does serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D decrease during acute-phase response? A systematic review. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, A.; Ochola, J.; Mundy, J.; Jones, M.; Kruger, P.; Duncan, E.; Venkatesh, B. Acute fluid shifts influence the assessment of serum vitamin D status in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, D.; Toole, B.J.; Knox, S.; Talwar, D.; Harten, J.; O’Reilly, D.S.J.; Blackwell, S.; Kinsella, J.; McMillan, D.C.; Wallace, A.M.; et al. The relation between acute changes in the systemic inflammatory response and plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations after elective knee arthroplasty. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waldron, J.L.; Ashby, H.; Cornes, M.; Bechervaise, J.; Razavi, C.; Thomas, O.L.; Chugh, S.; Deshpande, S.; Ford, C.; Gama, R. Vitamin D: A negative acute phase reactant. J. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 66, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.V.; Trump, N.L.; Johnson, C.S.; Feldman, D. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention and treatment. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 39, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newens, K.; Filteau, S.; Tomkins, A. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D does not vary over the course of a malarial infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 100, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, U.C.; Novovic, S.; Andersen, A.M.; Fenger, M.; Hansen, M.B.; Jensen, J.-E.B. Variations in Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D during Acute Pancreatitis: An Exploratory Longitudinal Study. Endocr. Res. 2011, 36, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoldo, F.; Pancheri, S.; Zenari, S.; Boldini, S.; Giovanazzi, B.; Zanatta, M.; Valenti, M.T.; Carbonare, L.D.; Cascio, V.L. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels modulate the acute-phase response associated with the first nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate infusion. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Swalih, M.; Patel, P.; Smith, M.A.; Perrin, R. Vitamin D Supplementation in COVID-19 Patients. Am. J. Ther. 2020, 27, e485–e490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M.E.; Costa, L.M.E.; Barrios, J.M.V.; Díaz, J.F.A.; Miranda, J.L.; Bouillon, R.; Gomez, J.M.Q. Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, M.S.; Romero, M.J.G.D.T. Cholecalciferol or Calcifediol in the Management of Vitamin D Deficiency. Nutrients 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chi, J.; Dong, B.; Lv, W.; Shen, L.; Wang, Y. Comorbidities and the risk of severe or fatal outcomes associated with coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annweiler, C.; Hanotte, B.; De L’Eprevier, C.G.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Lafaie, L.; Célarier, T. Vitamin D and survival in COVID-19 patients: A quasi-experimental study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 105771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahi, M.; Armas, L.A.G.; Heaney, R.P. Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beard, J.A.; Bearden, A.; Striker, R. Vitamin D and the anti-viral state. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 50, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-M.; Jo, E.-K. Antimicrobial Peptides in Innate Immunity against Mycobacteria. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimitrov, V.; White, J.H. Species-specific regulation of innate immunity by vitamin D signaling. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 164, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Demaret, J. Vitamin D and Tuberculosis. Vitamin D 2018, 2, 915–935. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, J.J.; Vieth, R.; Umhau, J.C.; Holick, M.F.; Grant, W.B.; Madronich, S.; Garland, C.F.; Giovannucci, E. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol. Infect. 2006, 134, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, P.G.; Findlay, E.G.; Currie, S.M.; Davidson, D.J. Antiviral potential of cathelicidins. Futur. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crane-Godreau, M.A.; Clem, K.J.; Payne, P.; Fiering, S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Air Pollution Exacerbate COVID-19 through Suppression of Antiviral Peptide LL37. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.; Ekiz, T.; Ricci, V.; Kara, Ö.; Chang, K.-V.; Özçakar, L. ‘Scientific Strabismus’ or two related pandemics: Coronavirus disease and vitamin D deficiency. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürr, U.H.; Sudheendra, U.; Ramamoorthy, A. LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1408–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leikina, E.; Delanoe-Ayari, H.; Melikov, K.; Cho, M.-S.; Chen, A.; Waring, A.J.; Wang, W.; Xie, Y.; Loo, J.A.; I Lehrer, R.; et al. Carbohydrate-binding molecules inhibit viral fusion and entry by crosslinking membrane glycoproteins. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.; Bortolasci, C.C.; Puri, B.K.; Olive, L.; Marx, W.; O’Neil, A.; Athan, E.; Carvalho, A.F.; Maes, M.; Walder, K.; et al. The pathophysiology of sars-cov-2: A suggested model and therapeutic approach. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElvaney, O.J.; McEvoy, N.L.; McElvaney, O.F.; Carroll, T.P.; Murphy, M.P.; Dunlea, D.M.; Choileáin, O.N.; Clarke, J.; O’Connor, E.; Hogan, G.; et al. Characterization of the Inflammatory Response to Severe COVID-19 Illness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B.; Lahore, H.; McDonnell, S.L.; Baggerly, C.A.; French, C.B.; Aliano, J.L.; Bhattoa, H.P. Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Nutrients 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhaskar, S.; Sinha, A.; Banach, M.; Mittoo, S.; Weissert, R.; Kass, J.S.; Rajagopal, S.; Pai, A.R.; Kutty, S. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19—Immunopathological Mechanisms, Clinical Considerations, and Therapeutic Approaches: The REPROGRAM Consortium Position Paper. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fara, A.; Mitrev, Z.; Mitrev, Z.; Assas, B.M. Cytokine storm and COVID-19: A chronicle of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmudpour, M.; Roozbeh, J.; Keshavarz, M.; Farrokhi, S.; Nabipour, I. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The anger of inflammation. Cytokine 2020, 133, 155151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kox, M.; Waalders, N.J.B.; Kooistra, E.J.; Gerretsen, J.; Pickkers, P. Cytokine Levels in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 and Other Conditions. JAMA 2020, 324, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Luo, S.; Libby, P.; Shi, G.-P. Cathepsin L-selective inhibitors: A potentially promising treatment for COVID-19 patients. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 213, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.J.; Crooks, C.; Naja, M.; Ledlie, A.; Goulden, B.; Liddle, T.; Khan, E.; Mehta, P.; Martin-Gutierrez, L.; Waddington, E.K.; et al. COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation and escalation of patient care: A retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e594–e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.J.; Peltan, I.D.; Jensen, P.; Hoda, D.; Hunter, B.; Silver, A. Clinical criteria for covid-19-associated hyperinflammaotry syndrome: A cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-H.; Zhao, Y.-S.; Zhou, D.-X.; Zhou, F.-C.; Xu, F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Cytokine storms, hyper-inflammatory phenotypes, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Genes Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftahi, G.H.; Jangravi, Z.; Sahraei, H.; Bahari, Z. The possible pathophysiology mechanism of cytokine storm in elderly adults with COVID-19 infection: The contribution of “inflame-aging”. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojyo, S.; Uchida, M.; Tanaka, K.; Hasebe, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Murakami, M.; Hirano, T. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 2020, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, M.; Saito, J.; Zhao, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Hirota, K.; Ma, D. Inflammation triggered by sars-cov-2 and ace2 augment drives multiple organ failure of severe covid-19: Molecular mechanisms and implications. Inflammation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, M.; Martin, J.C. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: A key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.B.; Kwon, N.J.; Choi, S.J.; Kang, C.K.; Choe, P.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Yun, J.; Lee, G.W.; Seong, M.W.; Kim, N.J.; et al. Virus isolation from the first patient with sars-cov-2 in korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombardini, T.; Picano, E. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 as the Molecular Bridge between Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of COVID-19. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 784.e1–784.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benne, C.A.; Kraaijeveld, C.A.; Van Strijp, J.A.G.; Brouwer, E.; Harmsen, M.; Verhoef, J.; Van Golde, L.M.G.; Van Iwaarden, J.F. Interactions of Surfactant Protein a with Influenza A Viruses: Binding and Neutralization. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 171, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.M.; Whitsett, J.A.; Hartshorn, K.L.; Crouch, E.C.; Korfhagen, T.R. Surfactant Protein D Enhances Clearance of Influenza A Virus from the Lung In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 5868–5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phokela, S.S.; Peleg, S.; Moya, F.R.; Alcorn, J.L. Regulation of human pulmonary surfactant protein gene expression by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L617–L626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gemmati, D.; Bramanti, B.; Serino, M.L.; Secchiero, P.; Zauli, G.; Tisato, V. COVID-19 and Individual Genetic Susceptibility/Receptivity: Role of ACE1/ACE2 Genes, Immunity, Inflammation and Coagulation. Might the Double X-Chromosome in Females Be Protective against SARS-CoV-2 Compared to the Single X-Chromosome in Males? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Qiao, G.; Uskokovic, M.; Xiang, W.; Zheng, W.; Kong, J. Vitamin D: A negative endocrine regulator of the renin–angiotensin system and blood pressure. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolf, J.D. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavishi, C.; Maddox, T.M.; Messerli, F.H. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection and Renin Angiotensin System Blockers. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Speeckaert, M.M.; Delanghe, J.R. Association between low vitamin D and COVID-19: Don’t forget the vitamin D binding protein. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1207–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H. Vitamin D alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via regulation of the renin-angiotensin system. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7432–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, C.; Xu, P.; Li, G.; Qiao, Y.; Han, W.; Geng, C.; Liao, D.; Yang, M.; Chen, D.; Jiang, P. Vitamin D receptor activation regulates microglia polarization and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats and angiotensin II-exposed microglial cells: Role of renin-angiotensin system. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygun, H. Vitamin D can prevent COVID-19 infection-induced multiple organ damage. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittermann, A.; Ernst, J.B.; Birschmann, I.; Dittrich, M. Effect of Vitamin D or Activated Vitamin D on Circulating 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Concentrations: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanff, T.C.; O’Harhay, M.; Brown, T.S.; Cohen, J.B.; Mohareb, A.M. Is There an Association Between COVID-19 Mortality and the Renin-Angiotensin System? A Call for Epidemiologic Investigations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, D.; Gupta, P.; Banerjee, D. Letter: Does vitamin d have a potential role against Covid-19? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Gomez, J.M.; Castillo, M.E.; Bouillon, R. Vitamin d receptor stimulation to reduce acute respiratory distress syndrome (ards) in patients with Coronavirus sars-cov-2 infections: Revised ms sbmb 2020_166. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 202, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; Macary, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tecson, K.M.; McCullough, P.A. Endothelial dysfunction contributes to COVID-19-associated vascular inflammation and coagulopathy. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; McCullough, P.A.; Tecson, K.M. Vitamin D deficiency in association with endothelial dysfunction: Implications for patients withCOVID-19. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanikarla-Marie, P.; Jain, S.K. 1,25(OH) 2 D 3 inhibits oxidative stress and monocyte adhesion by mediating the upregulation of GCLC and GSH in endothelial cells treated with acetoacetate (ketosis). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 159, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.-H.; Meza, C.A.; Clarke, H.; Kim, J.-S.; Hickner, R.C. Vitamin D and Endothelial Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, J.; Hu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Dancer, R.C.A.; Parekh, D.; Gao-Smith, F.; Thickett, D.R.; Jin, S. Vitamin d attenuates lung injury via stimulating epithelial repair, reducing epithelial cell apoptosis and inhibits tgf-beta induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, A.; McAuley, D.F.; O’Kane, C. Matrix metalloproteinases in acute lung injury: Mediators of injury and drivers of repair. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ueland, T.; Holter, J.; Holten, A.; Müller, K.; Lind, A.; Ke, M.; Dudman, S.; Aukrust, P.; Dyrhol-Riise, A.; Heggelund, L.; et al. Distinct and early increase in circulating MMP-9 in COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e41–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timms, P.; Mannan, N.; Hitman, G.; Noonan, K.; Mills, P.; Syndercombe-Court, D.; Aganna, E.; Price, C.; Boucher, B.J. Circulating MMP9, vitamin D and variation in the TIMP-1 response with VDR genotype: Mechanisms for inflammatory damage in chronic disorders? QJM Int. J. Med. 2002, 95, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, A.K.; Timms, P.M.; Boucher, B.J.; Venton, T.R.; Ashcroft, A.T.; Skolimowska, K.H.; Newton, S.M.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Davidson, R.N.; Griffiths, C.J.; et al. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3inhibits matrix metalloproteinases induced byMycobacterium tuberculosisinfection. Immunology 2009, 127, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvin, M.R.; Alvarez, C.; Miller, J.I.; Prates, E.T.; Walker, A.M.; Amos, B.K.; Mast, E.A.; Justice, A.; Aronow, B.; Jacobson, D. A mechanistic model and therapeutic interventions for COVID-19 involving a RAS-mediated bradykinin storm. eLife 2020, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombart, A.F.; Pierre, A.; Maggini, S. A Review of Micronutrients and the Immune System–Working in Harmony to Reduce the Risk of Infection. Nutrients 2020, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rondanelli, M.; Miccono, A.; Lamburghini, S.; Avanzato, I.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Nichetti, M.; Perna, S. Self-Care for Common Colds: The Pivotal Role of Vitamin D, Vitamin C, Zinc, and Echinacea in Three Main Immune Interactive Clusters (Physical Barriers, Innate and Adaptive Immunity) Involved during an Episode of Common Colds—Practical Advice on Dosages and on the Time to Take These Nutrients/Botanicals in order to Prevent or Treat Common Colds. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, P.O.; Aspinall, R. Vitamin D Status and the Host Resistance to Infections: What It Is Currently (Not) Understood. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abhimanyu, A.; Coussens, A.K. The role of UV radiation and vitamin D in the seasonality and outcomes of infectious disease. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Griffiths, C.J.; Martineau, A.R. Vitamin D in the prevention of acute respiratory infection: Systematic review of clinical studies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 136, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, E.C.; Granados, A.; Luinstra, K.; Pullenayegum, E.M.; Coleman, B.L.; Loeb, M.; Smieja, M. Vitamin D3and gargling for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laaksi, I.; Ruohola, J.-P.; Tuohimaa, P.; Auvinen, A.; Haataja, R.; Pihlajamäki, H.; Ylikomi, T. An association of serum vitamin D concentrations < 40 nmol/L with acute respiratory tract infection in young Finnish men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cannell, J.J.; Vieth, R.; Willett, W.; Zasloff, M.; Hathcock, J.N.; White, J.H.; Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.J.; et al. Cod Liver Oil, Vitamin A Toxicity, Frequent Respiratory Infections, and the Vitamin D Deficiency Epidemic. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008, 117, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belančić, A.; Kresović, A.; Rački, V. Potential pathophysiological mechanisms leading to increased COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in obesity. Obes. Med. 2020, 19, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlak, E.; Ertürk, A.; Çağ, Y.; Sebin, E.; Gümüşdere, M. The effect of inflammatory cytokines and the level of vitamin D on prognosis in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 18302–18310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hope-Simpson, R.E. The role of season in the epidemiology of influenza. J. Hyg. 1981, 86, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Reeves, R.M.; Wang, X.; Bassat, Q.; Brooks, W.A.; Cohen, C.; Moore, D.P.; Nunes, M.; Rath, B.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global patterns in monthly activity of influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and metapneumovirus: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1031–e1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Nair, H. Global Seasonality of Human Seasonal Coronaviruses: A Clue for Postpandemic Circulating Season of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2? J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, J.; Pitzer, V.E.; Viboud, C.; Grenfell, B.T.; Lipsitch, M. Absolute humidity and the seasonal onset of influenza in the continental united states. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Zusinaite, E.; Shtaida, N.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; Valkonen, M.; Kantele, A.; Telling, K.; Lutsar, I.; Letjuka, P.; Metelitsa, N.; et al. Low Temperature and Low UV Indexes Correlated with Peaks of Influenza Virus Activity in Northern Europe during 2010⁻2018. Viruses 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- France, S.P. Heatmap: Covid-19 Incidence per 100,000 Inhabitants by Age Group. Available online: https://guillaumepressiat.shinyapps.io/covid-si-dep/?reg=11%7c93%7c32 (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Phillips, N.; Park, I.-W.; Robinson, J.R.; Jones, H.P. The Perfect Storm: COVID-19 Health Disparities in US Blacks. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Gimenez, V.M.; Inserra, F.; Ferder, L.; Garcia, J.; Manucha, W. Vitamin d deficiency in african americans is associated with a high risk of severe disease and mortality by Sars-Cov-2. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T.; Kursumovie, E.; Lennane, S. Exclusive: Deaths of NHS staff from covid-19 analysed. Health Serv. J. 2020, 7027471. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, F.L.; Steur, M.; Allen, E.N.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans: Results from the EPIC–Oxford study. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, A.B. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1965, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Annweiler, C.; Cao, Z.; Sabatier, J.-M. Point of view: Should COVID-19 patients be supplemented with vitamin D? Maturitas 2020, 140, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejnmark, L.; Bislev, L.S.; Cashman, K.D.; Eiríksdottir, G.; Gaksch, M.; Gruebler, M.; Grimnes, G.; Gudnason, V.; Lips, P.; Pilz, S.; et al. Non-skeletal health effects of vitamin D supplementation: A systematic review on findings from meta-analyses summarizing trial data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zisi, D.; Challa, A.; Makis, A. The association between vitamin D status and infectious diseases of the respiratory system in infancy and childhood. Hormones 2019, 18, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sackett, D.L. Evidence-based medicine. Semin. Perinatol. 1997, 21, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concato, J. Observational Versus Experimental Studies: What’s the Evidence for a Hierarchy? NeuroRX 2004, 1, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidich, A.B. Meta-analysis in medical research. Hippokratia 2010, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Garattini, S.; Jakobsen, J.C.; Wetterslev, J.; Bertele, V.; Banzi, R.; Rath, A.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.E.; Laville, M.; Masson, Y.; Hivert, V.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice: Overview of threats to the validity of evidence and how to minimise them. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 32, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murthi, P.; Davies-Tuck, M.; Lappas, M.; Singh, H.; Mockler, J.; Rahman, R.; Lim, R.; Leaw, B.; Doery, J.; Wallace, E.M.; et al. Maternal 25-hydroxyvitamin D is inversely correlated with foetal serotonin. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 86, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urashima, M.; Segawa, T.; Okazaki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Wada, Y.; Ida, H. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in schoolchildren. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganmaa, D.; Uyanga, B.; Zhou, X.; Gantsetseg, G.; Delgerekh, B.; Enkhmaa, D.; Khulan, D.; Ariunzaya, S.; Sumiya, E.; Bolortuya, B.; et al. Vitamin D Supplements for Prevention of Tuberculosis Infection and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwitonze, A.M.; Razzaque, M.S. Role of Magnesium in Vitamin D Activation and Function. J. Am. Osteopat. Assoc. 2018, 118, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caspi, R.; Altman, T.; Dreher, K.; Fulcher, C.A.; Subhraveti, P.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Latendresse, M.; Mueller, L.A.; et al. The metacyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the biocyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D742–D753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swaminathan, R. Magnesium Metabolism and its Disorders. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2003, 24, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Noronha, L.J.; Matuschak, G.M. Magnesium in critical illness: Metabolism, assessment, and treatment. Intensiv. Care Med. 2002, 28, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddir, M.; Brito, A.; Dingeo, G.; Del Campo, S.S.F.; Samouda, H.; La Frano, M.R.; Bohn, T. Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusciano, D.; Bagnoli, P.; Galeazzi, R. The fight against covid-19: The role of drugs and food supplements. J. Pharm. Pharm. Res. 2020, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, K.; Ejaz, H.; Abdalla, A.E.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Ullah, M.I.; Yasmeen, H.; Younas, S.; Hamam, S.S.M.; Rehman, A. Effective immune functions of micronutrients against Sars-Cov-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahore, H. Covid-19 Intervention Trial Summary. Available online: https://vitamindwiki.com/tiki-index.php?page_id=11728 (accessed on 26 July 2020).

| Location | Participants | Outcomes vs. 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | Strengths, Limitations | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UK | 449 C19 patients 348,598 controls from UK Biobank | Incidence for 25(OH)D <10 vs. >10 Univariable OR = 1.37 (1.07–1.76, p = 0.01) Multivariable OR = 0.92 (0.71–1.21, p = 0.56) | Some confounding variables should not be used since they affect 25(OH)D concentrations [19,20] 25(OH)D data were from blood drawn from 2006 to 2010 Participant 25(OH)D concentrations change over time, reducing correlations with disease outcomes [21] | Hastie [22] |

| 2 | Switzerland | 27 patients PCR+ for SARS-CoV-2; 80 patients PCR– 1377 controls with 25(OH)D measured in same period in 2019 | Patients PCR+ had mean 25(OH)D = 11 vs. 25 for patients PCR– (p = 0.004) Controls had 25(OH)D = 25, not significantly different from patients PCR– (p = 0.08) | PCR+ is for antibodies; may not be active COVID-19 Small number of PCR+ | D’Avolio [23] |

| 3 | UK, Newcastle upon Tyne | 92 C19, non-ITU; 42 C19, ITU Patients were supplemented with vitamin D3 at doses inversely correlated with baseline 25(OH)D concentration | Non-ITU vs. ITU: 25(OH)D 19 ± 15 vs. 13 ± 7 (p = 0.30) 25(OH)D <20 vs. >20 (p = 0.02) RR for death, 25(OH)D = 0.97 (0.42–2.23, p = 0.94) | Lack of correlation of death with baseline 25(OH)D was likely due to graded supplementation with vitamin D | Panagiotou [24] |

| 5 | Italy | 42 C19 hospitalized patients; mean age 65 ± 13 years, 88 with ARDS | !L6 for 25(OH)D >30: 80 ± 40 pg/L; for 25(OH)D <10, 240 ± 470 pg/L After 10 days, patients with 25(OH)D <10 had a 50% mortality vs. 5% for 25(OH)D <10 (p = 0.02) | Patients with 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL had a mean age of 74 ± 11 years vs. 63 ± 15 years for patients with 25(OH)D ≥10 ng/mL | Carpagnano [25] |

| 6 | Korea | 50 C19 patients with PCR+, 150 controls; mean age = 52 ± 20 years | C19 vs. control: 16 (SD 8) vs. 25 (SD 13) (p < 0.001); ≤20, 74% vs. 43% (p = 0.003); ≤10, 24% vs. 7% (p = 0.001) | Strengths: measured B vitamin, folate, selenium and zinc concentrations as well as 25(OH)D Weaknesses: small number of patients; incomplete analysis of data for C19 outcomes | Im [26] |

| 7 | Russia | 80 C19 patients with community-acquired pneumonia | Severe: 25(OH)D = 12 ± 6 ng/mL; moderate to severe: 25(OH)D = 19 ± 14 ng/mL Death: 25(OH)D = 11 ± 6 ng/mL; discharged: 18 ± 6 ng/mL Obesity rates: 62% for severe, 15% for discharged, p < 0.001 | Strengths: studied the effect of obesity Weaknesses: small numbers | Karonova [27] |

| 8 | Mexico | 172 hospitalized C19 patients | Mean 25(OH)D = 17 ± 7 ng/mL for hospitalized C19 patients Survivors: mean age = 48 ± 13 years; 25(OH)D = 17 ± 7 ng/mL Death: mean age = 65 ± 12 years; 25(OH)D = 14 ± 6 ng/mL (p value for difference in 25(OH)D = 0.0008) | Weaknesses: survivors were much younger than non-survivors Comorbid factors not reported | Tort [28] |

| 9 | UK | 105 patients with C19 symptoms; 70 C19 PCR+, 35 PCR–; mean age = 80 ± 10 years | PCR+: 25(OH)D = 11 (8–19); PCR–: 25(OH)D = 21 (13–129) (p = 0.0008) Comorbid diseases were not significantly correlated with ≤12 vs. >12; | PCR+ is for antibodies; may not be active COVID-19 | Baktash [29] |

| 10 | UK | 656 C19, 203 died from C19; 340,824 controls from UK Biobank | Incidence for 25(OH)D <10 vs. >10 Univariable OR = 1.56 (1.28–1.90, p < 0.0001) Multivariable OR = 1.10 (0.88–1.37, p = 0.40) Death for 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL vs. >10 ng/mL Univariable OR = 1.61 (1.14–2.27, p = 0.0007) Multivariable OR = 1.21 (0.83–1.76, p = 0.31) | Same comments as for earlier UK Biobank study | Hastie [30] |

| 11 | Germany | 185 C19; median age = 60 years | Multivariable HR for death for 25(OH)D <12: IMV/D, 6.1 (2.8–13.4, p < 0.001); D, 14.7 (4.2–52.2, p < 0.001) | Strengths: HR adjusted for age, gender, and comorbidities Weaknesses: Small number of IMV and deaths | Radujkovic [31] |

| 12 | Austria | 109 C19 hospitalized patients; mean age = 58 ± 14 years | Mild: 26 ± 12 Moderate: 22 ± 8 Severe: 20 ± 10 (p = 0.12) PTH increased significantly with age (p = 0.001) | The vitamin D finding may have been limited owing to the high mean 25(OH)D concentrations Mild C19 patients had mean age = 46 ± 16 years; moderate and severe patients has mean age = 60 ± 13 years PTH increases with age [32] | Pizzini [33] |

| 13 | Spain | 80 emergency department patients with a PCR+ test within the past three months; retrospective study | 49 non-severe C19, 25(OH)D = 19 ng/mL; 31 severe C19, 25(OH)D = 13 ng/mL (p = 0.15) For patients under 65 years, 30 non-severe C19, 25(OH)D = 22 (11–31) ng/mL; 10 severe C19, 25(OH)D = 11 (9–12) ng/mL (p = 0.009) Multivariable OR for severe C19 for 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL = 3.2 (95% CI, 0.9 to 11.4, p = 0.07) | Weaknesses: small study; prevalence of advanced chronic kidney disease was higher in severe than non-severe cases (45% vs. 24%, p = 0.054) | Macaya [34] |

| 14 | China | 62 C19 patients, 80 healthy controls | age, 25(OH)D: controls: 43 years, 29 (23–33) ng/mL; mild/moderate C19: 39 (30–49) years, 23 (18–27) ng/mL; severe/critical C19: 65 (54–69) years, 15 (13–20) ng/mL Multivariate OR for severe/critical C19 for 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL = 15 (1.2 to 187, p = 0.03) | Strengths: many factors measured Weaknesses: the severe/critical patients were much older than mild/moderate patients and controls | Ye [35] |

| Location | Participants | Outcomes vs. 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | Strengths, Limitations | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Israel | Data from a hospital in Tel Aviv involving patients who had previous 25(OH)D measurements and were tested for SARS-CoV-2 using PCR 782 patients PCR+ 7025 patients PCR– | Univariate: 20–29 vs. >30: OR = 1.59 (1.24–2.02, p = 0.005); <20 vs. >30, OR = 1.58 (1.13–2.09, p = 0.0002). Multivariate: <30 vs. >30, OR = 1.50 (1.13–1.98, p = 0.001) | Strengths: large number of participants. Weakness: PCR+ is not COVID-19. | Merzon [36] |

| 2 | US | 489 C19 patients, PCR+; mean age = 49 ± 18 years with 25(OH)D concentrations were from preceding 12 months | 124 <20 vs. 287 >20, RR = 1.77 (1.12–2.81, p = 0.02) | Strengths: this is a retrospective study in which serum 25(OH)D concentrations and vitamin D supplementation history were obtained during the preceding 12 months. | Meltzer [37] |

| 3 | US | 191,779 patients tested for 25(OH)D and SARS-CoV-2 positivity during the past year by Quest Diagnostics | SARS-CoV-2 positivity for 25(OH)D <20 = 12.5% (95% CI, 12.2–12.8%); positivity for 25(OH)D >55 = 5.9% (95% CI, 5.5–6.4%). For 25(OH)D <20, SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates were: black non-Hispanic, 19%; Hispanic, 16%; white non-Hispanic, 9% | Strengths: large number of participants and is a retrospective study. 25(OH)D concentrations were seasonally adjusted. Weaknesses: SARS-CoV-2 positivity is a precursor to COVID-19, but many with positivity do not develop COVID-19. There may be bias in who was tested since the tests were ordered by physicians. | Kaufman[38] |

| Criterion | Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strength of association | A retrospective study in Chicago found a 77% increased risk of COVID-19 for 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL vs. >20 ng/mL | [37] |

| Consistency | Thirteen of 16 observational studies of COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 positivity reported inverse correlations with respect to 25(OH)D concentration. Two studies that did not find an inverse association used 25(OH)D values from more than a decade prior to COVID-19 and in the multivariable analysis used some confounding factors that affect 25(OH)D | Table 1 and Table 2 |

| Temporality | Four retrospective studies found inverse correlations between serum 25(OH)D and incidence of COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 positivity | [34,36,37,38] |

| Biological gradient | The large observational study of SARS-CoV-2 positivity found a large decrease as serum 25(OH)D increased from <20 to 50 ng/mL | [38] |

| Plausibility | Mechanisms have been proposed to explain how vitamin D reduces risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 | Discussed in this review |

| Coherence with known facts | Serum 25(OH)D concentrations are inversely correlated with risk and outcome of many diseases, also supported by RCTs in several cases | [5,7,8,44,139] |

| Experiment | Two intervention studies provide weak experimental support. Many RCTs are either planned or in progress to evaluate the role of vitamin D supplementation on COVID-19 risk and outcomes [18] | [58,59] |

| Analogy | Vitamin D supplementation reduces risk of some acute respiratory tract infections | [8] |

| Account for confounding factors | Univariate or multivariate regression analyses with confounding factors | [29,31,36,37] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mercola, J.; Grant, W.B.; Wagner, C.L. Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113361

Mercola J, Grant WB, Wagner CL. Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity. Nutrients. 2020; 12(11):3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113361

Chicago/Turabian StyleMercola, Joseph, William B. Grant, and Carol L. Wagner. 2020. "Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity" Nutrients 12, no. 11: 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113361

APA StyleMercola, J., Grant, W. B., & Wagner, C. L. (2020). Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity. Nutrients, 12(11), 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113361