Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

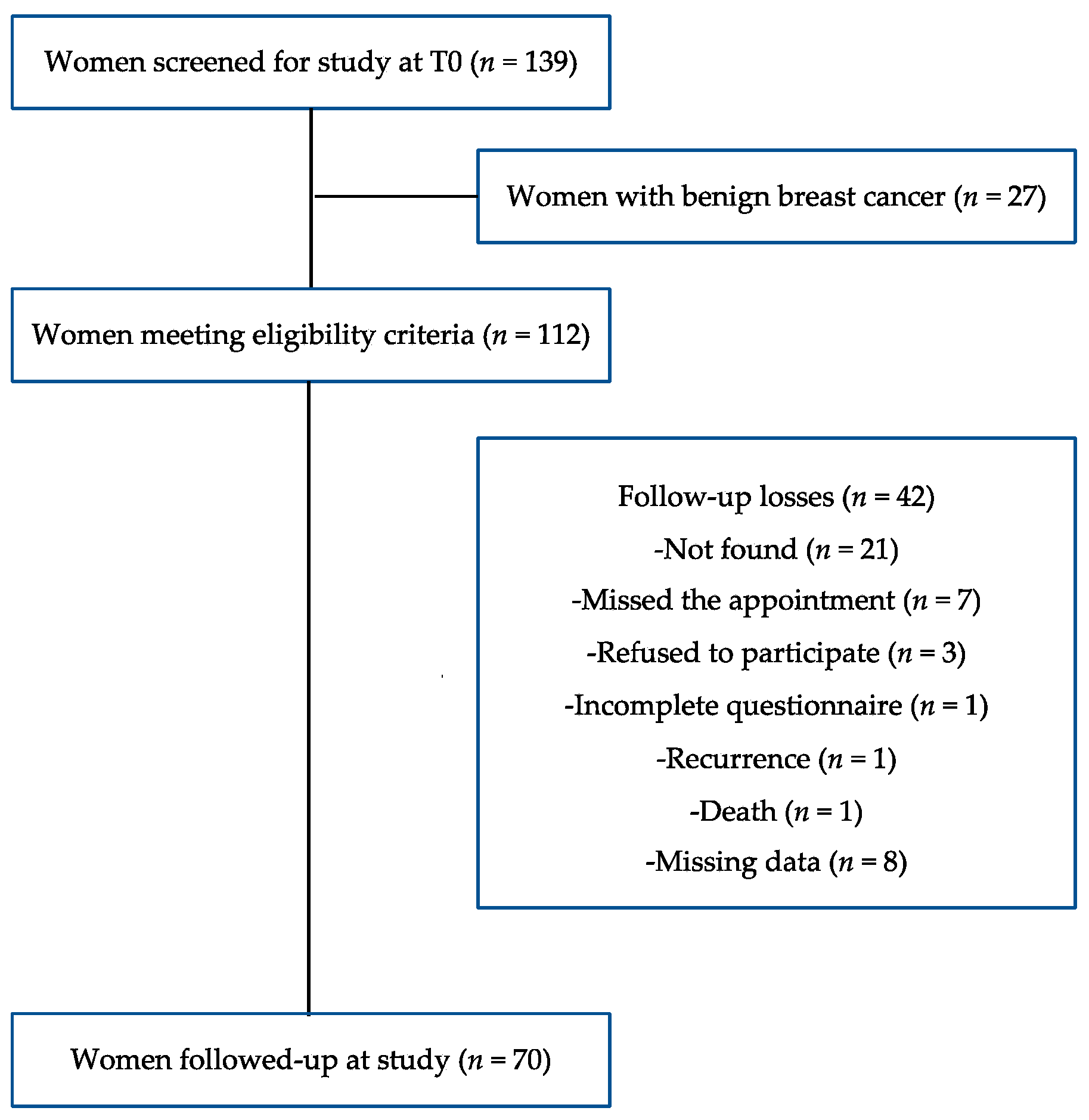

2.1. Study Design, Sampling and Ethics

2.2. Sociodemographic, Anthropometric and Clinical Data

2.3. Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

2.4. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers Analyses

2.4.1. Blood Collection

2.4.2. Antioxidant Biomarkers Analyses

2.4.3. Oxidation Biomarkers Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Seigel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomatarm, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer: Estimativa 2020: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil; Instituto Nacional de Câncer: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019.

- Rojas, K.; Stuckey, A. Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 59, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.N.; Schwab, R.B.; Martinez, M.E. Reproductive Risk Factors and Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Review of the Literature. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 144, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACS—American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figure 2013 Figure 2014. Available online: httpss://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancerorg/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-factsand-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2013-2014.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Goldhirsch, A.; Wood, W.C.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.J. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: Highlights of the St. gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluchino, L.A.; Wang, H.R. Reactive Oxygen Species in Biology and Human Health, 1st ed.; Ahmad, S.I., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Gurer-Orhan, H.; Ince, E.; Konyar, D.; Saso, L.; Suzen, S. The Role of Oxidative Stress Modulators in Breast Cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 4084–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athreya, K.; Xavier, M.F. Antioxidants in the Treatment of Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetch, F.; Pessoa, C.F.; Gentile, L.B.; Rosenthal, D.; Carvalho, D.P.; Fortunato, R.S. The role of oxidative stress on breast cancer development and therapy. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 4281–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Bhori, M.; Kasu, Y.A.; Bhat, G.; Marar, T. Antioxidants as precision weapons in war against cancer chemotherapy induced toxicity—Exploring the armoury of obscurity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, E.B. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: Current state. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulcin, I. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khurana, R.K.; Jain, A.; Sharma, T.; Singh, B.; Kesharwani, P. Administration of antioxidants in cancer: Debate of the decade. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastmalchi, N.; Baradaran, B.; Latifi-Navid, S.; Safaralizadeh, R.; Khojasteh, S.M.B.; Amini, M.; Roshani, E.; Lotfinejad, P. Antioxidants with two faces toward cancer. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, E.M.; Mohamed, N.H.; Abdelgawad, A.A.M. Antioxidants: An Overview on the Natural and Synthetic Types. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2017, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosone, C.B.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Hutson, A.D.; McCann, W.E.; McCann, S.E.; Barlow, W.E.; Kelly, K.M.; Cannioto, R.; Sucheston-Campbell, L.E.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Dietary supplement use during chemotherapy and survival outcomes of patients with breast cancer enrolled in a cooperative group clinical trial (SWOG S0221). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, L.S.; Moffet, I.; Shade, S.; Emadi, A.; Knott, C.; Gorman, E.F.; D’Adamo, C. Risks and benefits of antioxidant dietary supplement use during cancer treatment: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljsak, B.; Milisav, I. The Role of Antioxidants in Cancer, Friends or Foes? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 5234–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchetti, T.; Turco, I.; Urbano, A.; Morresi, C.; Ferreti, G. Relationship of fruit and vegetable intake to dietary antioxidant capacity and markers of oxidative stress: A sex-related study. Nutrition 2019, 61, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsdorff, H.; Puchau, B.; Volp, A.C.P.; Barbosa, K.B.; Bressan, J.; Zulet, M.A.; Martínez, J.A. Dietary total antioxidant capacity is inversely related to central adiposity as well as to metabolic and oxidative stress markers in healthy young adults. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 22, 8–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serafini, M.; Del Rio, D. Understanding the association between dietary antioxidants, redox status and disease: Is the Total Antioxidant Capacity the right tool? Redox Rep. Commun. Free Radic. Res. 2004, 9, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiano, P.; Molina-Montes, E.; Molinuevo, A.; Huerta, J.M.; Romaguera, D.; Gracia, E.; Martín, V.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Moreno, V.; et al. Association study of dietary non-enzymatic antioxidant Capacity (NEAC) and colorectal cancer risk in the Spanish Multicase-Control Cancer (MCC-Spain) study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2229–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasanfar, B.; Toorang, F.; Maleki, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Zendehdel, K. Association between dietary total antioxidant capacity and breast cancer: A case-control study in a Middle Eastern country. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Jessri, M.; Houshiar-Rad, A.; Mirzaei, H.R.; Rashidkhani, B. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk among women. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pantavos, A.; Ruiter, R.; Feskens, E.F.; De Keuser, C.E.; Hofman, A.; Stricker, B.H.; Franco, O.H.; Jong, J.C.K. Total dietary antioxidant capacity, individual antioxidant intake and breast cancer risk: The Rotterdam study. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 2178–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, F.G.K. Características Sociodemográficas, Reprodutivas, Clínicas, Nutricionais e de Estresse Oxidativo de Mulheres com Câncer de Mama. Master’s Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro, P.F.; Medeiros, N.I.; Vieira, F.G.; Fausto, M.A.; Belló-Klein, A. Breast cancer in southern Brazil: Association with past dietary intake. Nutr. Hosp. 2007, 22, 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Rockenbach, G. Changes in Food Consumption and Oxidative Stress in Women with Breast Cancer during the Anticancer Treatment Period. Master’s Dissertation, Graduate Program in Nutrition, Health Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Union for International Cancer Control. TNM Classification for Malignant Tumors, 8th ed.; Brierley, J.D., Gospodarowicz, M.K., Wittekind, C., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- WHO—World Health Organization. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry; WHO Technical Report Series 854; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WHO—World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio. Report of WHO Expert Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IOM—Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sichieri, R.; Everhart, J.E. Validity of a Brazilian food frequency questionnaire against dietary recalls and estimated energy intake. Nutr. Res. 1998, 18, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, N. Food Intake and Plasma Antioxidant Levels in Women with Breast Cancer. Master’s Dissertation, Postgraduate Program in Nutrition, Health Sciences Center, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture and Supply of the State of São Paulo (Brazil). Food Crop Table. Available online: https://www.agricultura.sp.gov.br/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Pinheiro, A.B. Tabela Para Avaliação de Consumo Alimentar em Medidas Caseiras, 5th ed.; Atheneu: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008; 131p. [Google Scholar]

- NEPA—Center for Studies and Research in Food. Brazilian Food Composition Database, 4th ed.; NEPA: Campinas, Brazil, 2011; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service (USDA). National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 18. Nutrient Data Laboratory, 2005. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Carlsen, M.H.; Halvorsen, B.L.; Holte, K.; Bohn, S.K.; Dragland, S.; Sampson, L.; Willey, C.; Senoo, H.; Umezono, Y.; Sanada, C.; et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service (USDA). Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.2. 2015. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-database-flavonoid-content-selected-foods-release-32-november-2015 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service (USDA). Database for the Isoflavone Content of Selected Foods, Release 2.1. 2015. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-database-isoflavone-content-selected-foods-release-21-november-2015 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service (USDA). Database for the Proanthocyanidin Content of Selected Foods, Release 2. 2015. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-database-proanthocyanidin-content-selected-foods-release-2-2015 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde; Departamento de Atenção Básica. Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira, 2nd ed.; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; p. 156.

- Abbaoui, B.; Lucas, C.R.; Riedl, K.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Mortazavi, A. Cruciferous Vegetables, Isothiocyanates, and Bladder Cancer Prevention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, B.; Tramonte, V.L.C. Bioavailabilty of lycopene. Rev. Nutr. 2006, 19, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Neveu, V.; Vos, F.; Scalbert, A. Identification of the 100 richest dietary sources of polyphenols—An application of the Phenol-Explorer database. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, s112–s120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, L.S.; Fretes, R.M.; Brumovsky, L.A. Bioavailability and antioxidant effect of the Ilex Paraguariensis polyphenols. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 45, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, E.; Duron, O.; Kelly, B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963, 61, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nourooz-zadeh, J.; Tajaddini-sarmadi, J.; Wolff, S.P. Measurement of plasma hydroperoxide concentrations by the ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange assay in conjunction with triphenylphosphine. Anal. Biochem. 1994, 220, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterbauer, H.; Cheeseman, K. Determination of aldehydic lipid peroxidation products: Malonaldehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L.; Garland, D.; Oliver, C.N.; Amici, A.; Climent, I.; Lenz, A.G.; Ahn, B.W.; Shaltiel, S.; Stadtman, E.R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 464–478. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65 (Suppl. 4), 1220S–1228S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, L.K.; Baptista, S.L.; Santos, E.S.; Hinnig, P.F.; Rockenbach, G.; Vieira, F.G.; de Assis, M.A.A.; da Silva, E.L.; Boaventura, B.C.B.; Di Pietro, P.F. Diet Quality Is Associated with Serum Antioxidant Capacity in Women with Breast Cancer: A Cross Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.L.D.; Custódiom, I.D.D.; Silva, A.T.F.; Ferreira, I.C.C.; Marinho, E.C.; Caixeta, D.C.; Souza, A.V.; Teixeira, R.R.; Araújo, T.G.; Shivappa, N.; et al. Overweight Women with Breast Cancer on Chemotherapy Have More Unfavorable Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Profiles. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, E.E.; Abba, M.C.; Lacunza, E.; Fernánde, E.; Guerci, A.M. Polymorphic variants in oxidative stress genes and acute toxicity in breast cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 3, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perillo, B.; Di Donato, M.; Pezone, A.; Zazzo, E.D.; Giovannelli, P.; Galasso, G.; Castoria, G.; Migliaccio, A. ROS in cancer therapy: The bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Mills, K.; Cessie, S.I.; Noordam, R.; Heemst, D.V. Ageing, age-related diseases and oxidative stress: What to do next? Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 57, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimta, A.A.; Tigu, A.B.; Muntean, M.; Cenariu, D.; Slaby, O.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Molecular links between central obesity and breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castegna, A.; Aksenov, M.; Thongboonkerd, V.; Klein, J.B.; Pierce, W.M.; Booze, R.; Markesbery, D.; Butterfield, D.A. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Part II: Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2, alpha-enolase and heat shock cognate 71. J. Neurochem. 2002, 82, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thanan, R.; Oikawa, S.; Yongvanit, P.; Hiraku, Y.; Ma, N.; Pinlaor, S.; Pairojkul, C.; Wongkham, C.; Sripa, B.; Khuntikeo, N.; et al. Inflammation-induced protein carbonylation contributes to poor prognosis for cholangiocarcinoma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannello, F.; Tonti, G.A.; Medda, V. Protein oxidation in breast microenvironment: Nipple aspirate fluid collected from breast cancer women contains increased protein carbonyl concentration. Cell Oncol. 2009, 31, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, D.; Negi, R.; Karki, K.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, R.S.; Khanna, H.D. Oxidative damage markers as possible discriminatory biomarkers in breast carcinoma. Transl. Res. 2012, 160, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.Y.; Suh, Y.J.; Kim, S.W.; Baik, H.W.; Sung, C.J.; Kim, H.S. Evaluation of dietary factors in relation to the biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in breast cancer risk. Nutrition 2011, 27, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarova, P.; Kalousova, M.; Trnkova, B.; Soukupova, J.A.; Argalasova, S.; Petruzelka, L.; Zima, T. Carbonyl and oxidative stress in patients with breast cancer: Is there a relation to the stage of the disease? Neoplasma 2007, 54, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balci, H.; Genc, H.; Papila, C.; Can, G.; Papila, B.; Yanardag, H.; Uzun, H. Serum lipid hydroperoxide levels and paraoxonase activity in patients with lung, breast, and colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2012, 26, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossner, P.; Terry, M.B.; Gammon, M.D.; Agrawal, M.; Zhang, F.F.; Ferris, J.S.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Eng, S.M.; Gaudet, M.M.; Neugut, A.I.; et al. Plasma protein carbonyl levels and breast cancer risk. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Cai, Q.; Shu, X.O.; Nechuta, S.J. The Role of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer Risk and Prognosis: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiologic Literature. J. Womens Health (Larchmt.) 2017, 26, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sateesh, R.; Bitla, A.R.R.; Bugudu, S.R.; Mutheeswariah, Y.; Narendra, H.; Phaneedra, B.V.; Lakshmi, A.Y. Oxidative stress in relation to obesity in breast cancer. Indian J. Cancer 2019, 56, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Rajendran, R.; Kuroda, K.; Isogai, E.; Krstic-Demonacos, M.; Demonacos, C. Oxidative stress and breast cancer biomarkers: The case of the cytochrome P450 2E1. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2016, 2, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wirth, M.D.; Murphy, E.A.; Hurley, T.G.; Hébert, J.R. Effect of Cruciferous Vegetable Intake on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers: Differences by Breast Cancer Status. Cancer Investig. 2017, 35, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, C.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Shaw, J.W.; Rock, C.L.; Ritenbaugh, K.; Hakim, I.A.; Hollenbach, K.A.; Alberts, D.S.; Pierce, J.P. Diet and Biomarkers of Oxidative Damage in Women Previously Treated for Breast Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2005, 51, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Meckling, K.A.; Marcone, M.F.; Kakuda, Y.; Tsao, R. Synergistic, Additive, and Antagonistic Effects of Food Mixtures on Total Antioxidant Capacities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.L.; He, D.H.; Cheng, Y.X. Protection against chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced side effects: A review based on the mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities of phytochemicals. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griñan-Lison, C.; Blaya-Cánovas, J.L.; López-Tejada, A.; Ávalos-Moreno, M.; Navarro-Ocón, A.; Cara, F.E.; González-González, A.; Lorente, J.A.; Marchal, J.A.; Granados-Principal, S. Antioxidants for the Treatment of Breast Cancer: Are We There Yet? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosone, C.B.; Ahn, J.; Schoenenberger, V. Antioxidant supplements, genetics and chemotherapy outcomes. Curr. Cancer Ther. Rev. 2005, 1, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.Y.; Cai, X.; Thoene, K.; Obi, N.; Jaskulski, S.; Bherens, S.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Chang-Claude, J. Antioxidant supplementation and breast cancer prognosis in postmenopausal women undergoing chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lesperance, M.L.; Olivotto, I.A.; Forde, N.; Zhao, Y.; Speers, C.; Foster, H.; Tsao, M.; MacPherson, N.; Hoffer, A. Mega-dose vitamins and minerals in the treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer: An historical cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002, 76, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INCA—José Alencar Gomes da Silva National Cancer Institute—Ministry of Health. National Consensus of Oncologycal Nutrition. 2016. Available online: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files/media/document/consenso-nutricao-oncologica-vol-ii-2-ed-2016.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- WCRF/AICR—World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: A Global Perspective. The Third Expert Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/diet-and-cancer/ (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Sznarkowska, A.; Kostecka, A.; Meller, K.; Bielawski, K.P. Inhibition of cancer antioxidant defense by natural compounds. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 15996–16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pierce, J.P.; Natarajan, L.; Caan, B.J.; Parker, B.A.; Greenberg, E.R.; Flatt, S.W.; Rock, C.L.; Kealey, S.; Al-Delaimy, W.K.; Bardwell, W.A.; et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA 2007, 298, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DaC Tertiles at T0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Tertile | 2nd Tertile | 3rd Tertile | p | |

| Age a (years) | 54.75 (12.0) 2 | 54.91 (8.82) 3 | 47.17 (9.25) | 0.016 * |

| Body Mass Index a (kg/m2) | 28.35 (5.54) 2 | 28.41 (3.84) 3 | 25.36 (3.35) | 0.030 * |

| Waist circumference a (cm) | 90.64 (16.1) | 92.39 (12.5) 3 | 83.33 (9.53) | 0.049 * |

| Physical Activity Level a | 1.34 (0.11) | 1.34 (0.10) | 1.37 (0.07) | 0.447 * |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (12.5) | 5 (21.7) | 8 (34.8) | 0.189 # |

| No | 21 (87.5) | 18 (78.3) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Alcohol, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 0.331 # |

| No | 24 (100) | 21 (91.3) | 21 (91.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 21 (87.5) | 22 (95.7) | 23 (100.0) | 0.172 # |

| Brown | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Education | ||||

| <8 years | 17 (70.8) | 17 (73.9) | 13 (56.5) | 0.755 # |

| 9–11 years | 4 (16.7) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Estrogen receptor +, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (59.1) | 18 (85.7) | 17 (85.0) | 0.070 # |

| No | 9 (40.9) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Progesterone receptor +, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (59.1) | 17 (80.9) | 16 (80.0) | 0.189 # |

| No | 9 (40.9) | 4 (19.1) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Her2 +, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 7 (41.2) | 0 (00.0) | 5 (5.5) | 0.099 # |

| No | 10 (58.8) | 7 (100) | 6 (54.5) | |

| Triple negative, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 5 (23.8) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (00.0) | 0.062 # |

| No | 16 (26.2) | 18 (90.0) | 19 (100.0) | |

| Tumor classification, n (%) | ||||

| Invasive carcinoma | 21 (87.5) | 22 (95.6) | 22 (95.6) | 0.454 # |

| Carcinoma in situ | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Tumor stage, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.524 # |

| I | 8 (33.3) | 9 (39.1) | 6 (26.1) | |

| II | 9 (37.5) | 8 (34.8) | 11 (47.8) | |

| III | 5 (20.8) | 6 (26.1) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Type of treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 5 (20.8) | 6 (26.1) | 5 (21.7) | 0.746 # |

| Chemotherapy | 6 (25.0) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Radiotherapy in association with chemotherapy | 10 (41.7) | 11 (47.8) | 8 (34.8) | |

| No treatment | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.35) | 1 (4.35) | |

| Hormone Therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Tamoxifen | 13 (54.2) | 14 (60.9) | 16 (69.6) | 0.313 # |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 1 (4.2) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (8.7) | |

| No treatment | 10 (41.7) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||||

| Partial mastectomy | 7 (29.2) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 0.914 # |

| Radical mastectomy | 11 (45.8) | 12 (52.2) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Sectorectomy | 6 (25.0) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (17.4) |

| Biomarker | Biomarker | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | p | T0 | T1 | p | ||

| DaC Tertile T0 | GSH (μmol/L) | DaC Tertile T1 | GSH (μmol/L) | ||||

| 1st tertile a | 76.6 (19.5) | 77.0 (26.1) | 0.958 * | 1st tertile a | 75.3 (19.9) | 76.9 (33.6) | 0.850 * |

| 2nd tertile a | 75.2 (26.3) | 75.3 (31.7) | 0.989 * | 2nd tertile a | 80.0. (22.1) | 84.9 (33.3) | 0.533 * |

| 3rd tertile a | 82.7 (17.5) | 85.8 (33.8) | 0.670 * | 3rd tertile a | 78.8 (22.9) | 75.5 (23.5) | 0.630 * |

| FRAP (μmol/L) | FRAP (μmol/L) | ||||||

| 1st tertile a | 617.5 (160.1) | 528.5 (154.9) | 0.070 * | 1st tertile a | 641.1 (176.5) | 554.2 (156.4) | 0.033 * |

| 2nd tertile a | 683.7 (160.4) | 589.8 (177.3) | 0.024 * | 2nd tertile a | 581.6 (148.6) | 587.9 (203.9) | 0.904 * |

| 3rd tertile a | 583.9 (153.9) | 607.8 (225.3) | 0.682 * | 3rd tertile a | 667.5 (152.1) | 579.4 (203.7) | 0.122 * |

| Lipid hydroperoxides-log (μmol/L) | Lipid hydroperoxides-log (μmol/L) | ||||||

| 1st tertile a | 1.38 (0.73) | 1.21 (1.13) | 0.520 * | 1st tertile a | 1.28 (0.70) | 1.52 (1.02) | 0.392 * |

| 2nd tertile a | 1.09 (0.76) | 1.43 (1.20) | 0.294 * | 2nd tertile a | 1.24 (0.81) | 1.23 (1.09) | 0.978 * |

| 3rd tertile a | 1.39 (0.75) | 1.30 (1.5) | 0.773 * | 3rd tertile a | 1.33 (0.77) | 1.17 (1.67) | 0.665 * |

| Carbonylated proteins-log (μmol/L) | Carbonylated proteins-log (μmol/L) | ||||||

| 1st tertile a | −0.38 (0.35) | −0.04 (0.06) | 0.002 * | 1st tertile a | −0.33 (0.40) | 0.03 (0.23) | <0.001 * |

| 2nd tertile a | −0.35 (0.50) | −0.09 (0.03) | 0.019 * | 2nd tertile a | −0.21 (0.43) | −0.10 (0.17) | 0.300 * |

| 3rd tertile a | −0.04 (0.23) | −0.06 (0.45) | 0.888 * | 3rd tertile a | −0.24 (0.44) | −0.09 (0.22) | 0.220 * |

| TBARS-log (μmol/L) | TBARS-log (μmol/L) | ||||||

| 1st tertile a | 1.56 (0.41) | 2.16 (0.75) | 0.006 * | 1st tertile a | 1.62 (0.47) | 2.04 (0.64) | 0.037 * |

| 2nd tertile a | 1.68 (0.29) | 1.98 (0.71) | 0.115 * | 2nd tertile a | 1.64 (0.51) | 2.03 (0.80) | 0.060 * |

| 3rd tertile a | 1.64 (0.61) | 1.89 (0.68) | 0.170 * | 3rd tertile a | 1.62 (0.37) | 1.97 (0.74) | 0.070 * |

| T0 | T1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st DaC Tertile | 2nd DaC Tertile | 3rd DaC Tertile | p | 1st DaC Tertile | 2nd DaC Tertile | 3rd DaC Tertile | p | |

| aC from whole cereals, legumes, tubers and roots (mmol/d) a | 0.45 (0.24–0.91) | 0.41 (0.30–0.80) | 0.63 (0.26–1.01) | 0.736 | 0.54 (0.30–0.68) | 0.51 (0.26–0.70) | 0.92 (0.52–1.75) | 0.005 * |

| aC from Total fruits (mmol/d) a | 0.93 (0.67–1.46) | 1.22 (0.70–2.06) | 1.55 (0.53–2.46) | 0.215 | 1.12 (0.71–1.83) | 0.82 (0.44–1.45) | 2.06 (1.14–3.02) | 0.002 * |

| aC from Total vegetables (mmol/d) a | 0.37 (0.19–0.50) | 0.35 (0.19–0.55) | 0.39 (0.30–0.60) | 0.260 | 0.38 (0.17–0.54) | 0.27 (0.19–0.40) | 0.55 (0.30–0.95) | 0.040 * |

| aC from Cruciferous vegetables (mmol/d) a | 0.14 (0.05–0.30) | 0.10 (0.03–0.30) | 0.13 (0.04–0.21) | 0.902 | 0.06 (0.00–0.29) | 0.09 (0.04–0.16) | 0.18 (0.07–0.35) | 0.044 * |

| aC from Orange and dark green vegetables and fruits (mmol/d) a | 0.44 (0.19–0.82) | 0.65 (0.33–1.57) | 0.75 (0.36–2.15) | 0.157 | 0.34 (0.18–0.66) | 0.37 (0.20–0.65) | 0.58 (0.26–1.01) | 0.141 * |

| aC from Citric fruits (mmol/d) a | 0.23 (0.11–0.56) | 0.56 (0.10–1.22) | 0.50 (0.18–2.03) | 0.186 | 0.28 (0.13–0.41) | 0.22 (0.14–0.37) | 0.43 (0.21–0.62) | 0.010 * |

| aC from Red vegetables and fruits (mmol/d) a | 0.07 (0.03–0.31) | 0.08 (0.03–0.39) | 0.08 (0.03–0.49) | 0.853 | 0.13 (0.05–0.43) | 0.07 (0.03–0.18) | 0.12 (0.04–1.46) | 0.255 * |

| aC from Polyphenol-rich foods and beverages (mmol/d) a | 4.21 (2.63–5.05) | 7.45 (6.35–8.38) | 12.14 (11.2–15.7) | 0.0001 | 3.77 (1.78–4.43) | 7.84 (7.44–9.17) | 12.0 (9.31–15.2) | 0.0001 * |

| Period | Oxidative Stress Biomarkers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBARS-Log * | LH-Log † | Carbonylated Proteins-Log ‡ | GSH § | FRAP II | ||||||

| ß-Adjusted (CI95%) | p | ß-Adjusted (CI95%) | p | ß-Adjusted (CI95%) | p | ß-Adjusted (CI95%) | p | ß-Adjusted (CI95%) | p | |

| T0 | −0.030 | 0.811 | 0.134 | 0.125 | 0.541 | −34.51 | ||||

| (−0.283/0.222) | (−0.283/0.552) | 0.522 | (−0.125/0.375) | 0.322 | (−10.41/11.49) | 0.922 | (−111.2/46.17) | 0.396 | ||

| T1 | −0.426 | −0.144 | −0.204 | −12.86 | −19.20 | |||||

| (−1.00/0.153) | 0.144 | (−1.25/0.961) | 0.794 | (−0.339/−0.070) | 0.004 | (−32.17/6.44) | 0.188 | (−130.3/91.92) | 0.731 | |

| Increased Oxidative Stress and Reduced Antioxidant Biomarkers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBARS-Log * | LH-Log † | Carbonylated Proteins-Log ‡ | GSH § | FRAP II | ||||||

| OR (CI95%) | p | OR (CI95%) | p | OR (CI95%) | p | OR (CI95%) | p | OR (CI95%) | p | |

| Reduced DaC (mmol/day) | 0.238 (0.067/0.838) | 0.025 | 8.06 (1.39/46.6) | 0.020 | 0.497 (0.147/1.680) | 0.261 | 0.200 (0.042/0.956) | 0.044 | 0.126 (0.026/0.609) | 0.010 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reitz, L.K.; Schroeder, J.; Longo, G.Z.; Boaventura, B.C.B.; Di Pietro, P.F. Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124324

Reitz LK, Schroeder J, Longo GZ, Boaventura BCB, Di Pietro PF. Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study. Nutrients. 2021; 13(12):4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124324

Chicago/Turabian StyleReitz, Luiza Kuhnen, Jaqueline Schroeder, Giana Zarbato Longo, Brunna Cristina Bremer Boaventura, and Patricia Faria Di Pietro. 2021. "Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study" Nutrients 13, no. 12: 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124324

APA StyleReitz, L. K., Schroeder, J., Longo, G. Z., Boaventura, B. C. B., & Di Pietro, P. F. (2021). Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study. Nutrients, 13(12), 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124324